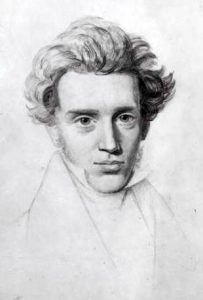

37 Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard, 1813 – 1855 CE, was a Danish philosopher, theologian, poet, and social critic who is considered to be the first existentialist philosopher in history. Kierkegaard’s work focused mostly on Christian ethics, the institution of the Church, and the differences between logic and the attempt to find factual, objective proofs of Christianity in contrast to recognizing the individual’s subjective relationship to God. Much of his work deals with defining or having Christian love. His work explored emotions of individuals when faced with life choices.

“But in relation to God, there are no secret instructions for a human being any more than there are any backstairs. Even the most eminent genius who comes to give a report had best come in fear and trembling, for God is not hard pressed for geniuses. He can create a few legion of them if needed.”

by Søren Kierkegaard, from Fear and Trembling published in 1843 under the pseudonym Johannes de silentio (John of the Silence)

Because the English translations of Kierkegaard are not in the public domain as yet, we can only quote portions of his work in English.

Start with two radio broadcasts that help explain Søren Kirkegaard. One is called “Fear and Trembling in Copenhagen – In Search of Søren Kierkegaard” recorded by the BBC in consultation with Nigel Warburton.

BBC Program about Soren Kierkegaard

And the other is called “Kierkegaard 200” and is broadcast through The Philosopher’s Zone, with guests Dr. Patrick Stokes of Deakin University in Australia, Dr. Hubert Dreyfus, late of UC Berkely, and Dr. Tim Reynor.

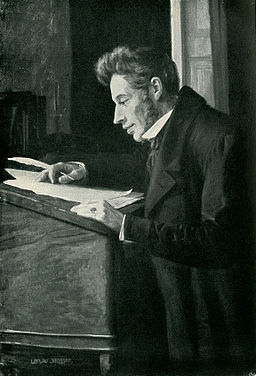

![drawing of Kierkegaard by Wilhelm Marstrand [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/194/2018/03/Kierkegaard_1870_by_Marstrand.jpg) One of Kierkegaard’s works, “Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments” is famous for its general statement, Subjectivity is Truth. It was an attack on deterministic philosophy. What Kierkegaard is saying, generally, is that truth is not just bound to the discovery of objective facts. Real truth is based on how humans connect to those facts. In ethics, action is what is measured and seen and thus considered important, and so to Kierkegaard, truth is to be found in subjectivity of actions rather than the objectivity of facts alone. A fact is not enough. What one does with that fact really matters.

One of Kierkegaard’s works, “Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments” is famous for its general statement, Subjectivity is Truth. It was an attack on deterministic philosophy. What Kierkegaard is saying, generally, is that truth is not just bound to the discovery of objective facts. Real truth is based on how humans connect to those facts. In ethics, action is what is measured and seen and thus considered important, and so to Kierkegaard, truth is to be found in subjectivity of actions rather than the objectivity of facts alone. A fact is not enough. What one does with that fact really matters.

Kierkegaard is especially well know for his disagreement with the work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, a German 18th-19th century philosopher, and for his dislike of both Hegel’s insistence on Logic and Hegel’s further claim that he had devised a system of thought that could explain the whole of reality. He considered that claim–that he had a handle on reality– a form of arrogance.

In a journal entry made in 1844, Kierkegaard wrote:

“If Hegel had written the whole of his logic and then said, in the preface or some other place, that it was merely an experiment in thought in which he had even begged the question in many places, then he would certainly have been the greatest thinker who had ever lived. As it is, he is merely comic.”

Kierkegaard attempted to deny Hegel’s insistence on logic within the realm of religion by suggesting that many doctrines of Christianity – including the doctrine of Incarnation, a God who is also human – cannot be explained with fact and rational thought. Kierkegaard insisted that faith has truth that facts may not be able to explain. Here he is encouraging the searching minds of the young.

“Let a doubting youth, but an existing doubter with youth’s lovable, boundless confidence in a hero of scientific scholarship, venture to find in Hegelian positivity the truth, the truth of existence-he will write a dreadful epigram on Hegel. Do not misunderstand me. I do not mean that every youth is capable of overcoming Hegel, far from it. If a young person is conceited and foolish enough to try that, his attack is inane. No, the youth must never think of wanting to attack him; he must rather be willing to submit unconditionally to Hegel with feminine devotedness, but nevertheless with sufficient strength also to stick to his question-then he is a satirist without suspecting it. The youth is an existing doubter; continually suspended in doubt, he grasps for the truth-so that he can exist in it. Consequently, he is negative, and Hegel’s philosophy is, of course, positive-no wonder he puts his trust in it. But for an existing person pure thinking is a chimera when the truth is supposed to be the truth in which to exist.

Having to exist with the help of the guidance of pure thinking is like having to travel in Denmark with a small map of Europe on which Denmark is no larger than a steel pen-point, indeed, even more impossible. The youth’s admiration, his enthusiasm, and his limitless confidence in Hegel are precisely the satire on Hegel. This would have been discerned long ago if pure thinking had not maintained itself with the aid of a reputation that impresses people, so that they dare not say anything except that it is superb, that they have understood it-although in a certain sense that it is indeed impossible, since no one can be led by this philosophy to understand himself, which is certainly an absolute condition for all other understanding.

Socrates has rather ironically said that he did not know for sure whether he was a human being or something else, but in the confessional a Hegelian can say with all solemnity: I do not know whether I am a human being-but I have understood the system.

I prefer to say: I know that I am a human being, and I know that I have not understood the system. And when I have said that very directly, I shall add that if any of our Hegelians want to take me into hand and assist me to an understanding of the system, nothing will stand in the way from my side. In order that I can learn all the more, I shall try hard to be as obtuse as possible, so as not to have, if possible, a single presupposition except my ignorance. And in order to be sure of learning something, I shall try hard to be as indifferent as possible to all charges of being unscientific and unscholarly. Existing, if this is to be understood as just any sort of existing, cannot be done without passion.”

Soren Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, Hong p. 310-311

This concept of “Existing, if this is to be understood as just any sort of existing, cannot be done without passion” is critical to understand Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard attempts to use the story of Abraham to show that there is a goal higher than that of ethics and that faith cannot be explained by Hegelian ethics. His work can be read as a challenge to the Hegelian notion that a human being’s ultimate purpose is to fulfill ethical demands. He is more concerned about the inner search and fight for faith than the outer world of action and ethical behavior.

This concept of “Existing, if this is to be understood as just any sort of existing, cannot be done without passion” is critical to understand Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard attempts to use the story of Abraham to show that there is a goal higher than that of ethics and that faith cannot be explained by Hegelian ethics. His work can be read as a challenge to the Hegelian notion that a human being’s ultimate purpose is to fulfill ethical demands. He is more concerned about the inner search and fight for faith than the outer world of action and ethical behavior.

“Let us speak further about the wish and thereby about sufferings. Discussion of sufferings can always be beneficial if it addresses not only the self-willfulness of the sorrow but, if possible, addresses the sorrowing person for his upbuilding. It is a legitimate and sympathetic act to dwell properly on the suffering, lest the suffering person become impatient over our superficial discussion in which he does not recognize his suffering, lest he for that reason impatiently thrust aside consolation and be strengthened in double-mindedness. It certainly is one thing to go out into life with the wish when what is wished becomes the deed and the task; it is something else to go out into life away from the wish.

Abraham had to leave his ancestral home an emigrate to an alien nation, where nothing reminded him of what he loved – indeed, sometimes it is no doubt a consolation that nothing calls to mind what one wishes to forget, but it is a bitter consolation for the person who is full of longing. Thus a person can also have a wish that for him contains everything, so that in the hour of the separation, when the pilgrimage begins, it is as if he were emigrating to a foreign country where nothing but the contrast reminds him, by the loss, of what he wished; it can seem to him as if he were emigrating to a foreign country even if he remains at home perhaps in the same locality – by losing the wish just as among strangers, so that to take leave of the wish seems to him harder and more crucial than to take leave of his senses.

|Apart from this wish, even if he still does not move from the spot, his life’s troublesome way is perhaps spent in useless sufferings, for we are speaking of those who suffer essentially, not of those who have the consolation that their sufferings are for the benefit of a good cause, for the benefit of others. It was bound to be thus – the journey to the foreign country was not long; in one moment he was there, there in that strange country where the suffering ones meet, but not those who have ceased to grieve, not those whose tears eternity cannot wipe away, for as an old devotional book so simply and movingly says, “How can God dry your tears in the next world if you have not wept?” Perhaps someone else comes in a different way, but to the same place.”

Søren Kierkegaard, Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, Hong 1993 p. 102-103

Kierkegaard would argue that a divine command from God transcends ethics. This means that God does not create human morality, that it is up to individuals to create morals and values. A religious person must be prepared for a command from God that would take precedence over all moral and even rational obligations. Kierkegaard called this event a teleological suspension of the ethical. Abraham, in the story, chose to obey God unconditionally and take his son, Isaac, up onto the mountain to sacrifice Isaac to God at God’s command, and was rewarded for this obedience and trust with his son’s life, given an alternative sacrifice and earned the title of Father of Faith. Abraham transcended ethics and leaped into faith.

But there is no good logical argument one can make to claim that morality ought to be or can be suspended in any given circumstance, or even ever. The choice to obey God unconditionally is a true existential ‘either/or’ decision faced by every individual. Either one chooses to live in faith (the religious stage) or to live ethically (the ethical stage). He clearly advocates for choosing the Religious Stage of living as the ultimate goal.

Kierkegaard, Søren . Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments. Translated by Edna H Hong and Howard V Hong, Princeton University Press, 1992.

Kierkegaard, Søren. Fear and Trembling. Edited and translated by Howard V and Edna H Hong, Princeton University Press, 1983

Kierkegaard, Søren. Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits. Translated by Edna H Hong and Howard V Hong, Princeton University Press, 1990.