38 Friedrich Nietzsche

BEYOND GOOD AND EVIL

Translated by Helen Zimmern

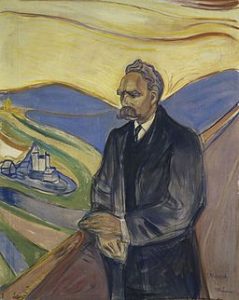

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, 1844 –1900 CE, was a German philosopher, cultural critic, Latin and Greek scholar whose work has had a strong influence on Western philosophy. He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest person ever to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in 1869 at the age of 24. He resigned in 1879 due to health problems, and he completed much of his writing after that. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and afterwards, a complete loss of his mental health. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897, and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche.

Nietzsche died of complications from syphilis in 1900. After his death his sister took control of her brother’s work. She rewrote Nietzsche’s unpublished writings to fit her own stridently German nationalist ideology while trying to contradict or muddy Nietzsche’s stated opinions, which opposed antisemitism and nationalism. Through her reworked editions, Nietzsche’s work became associated with fascism and the Nazi ideals. 20th century scholars fought against this interpretation of his work and corrected editions of his writings were published.

Most of us only run into Nietzsche when studying the Holocaust (it’s all his sister’s fault) or through Hollywood. So try starting here:

Excerpt from CHAPTER IX. WHAT IS NOBLE?

In a tour through the many finer and coarser moralities which have hitherto prevailed or still prevail on the earth, I found certain traits recurring regularly together, and connected with one another, until finally two primary types revealed themselves to me, and a radical distinction was brought to light.

In a tour through the many finer and coarser moralities which have hitherto prevailed or still prevail on the earth, I found certain traits recurring regularly together, and connected with one another, until finally two primary types revealed themselves to me, and a radical distinction was brought to light.

There is MASTER-MORALITY and SLAVE-MORALITY,—I would at once add, however, that in all higher and mixed civilizations, there are also attempts at the reconciliation of the two moralities, but one finds still oftener the confusion and mutual misunderstanding of them, indeed sometimes their close juxtaposition—even in the same man, within one soul. The distinctions of moral values have either originated in a ruling caste, pleasantly conscious of being different from the ruled—or among the ruled class, the slaves and dependents of all sorts. In the first case, when it is the rulers who determine the conception “good,” it is the exalted, proud disposition which is regarded as the distinguishing feature, and that which determines the order of rank.

The noble type of man separates from himself the beings in whom the opposite of this exalted, proud disposition displays itself he despises them. Let it at once be noted that in this first kind of morality the antithesis “good” and “bad” means practically the same as “noble” and “despicable”,—the antithesis “good” and “EVIL” is of a different origin. The cowardly, the timid, the insignificant, and those thinking merely of narrow utility are despised; moreover, also, the distrustful, with their constrained glances, the self-abasing, the dog-like kind of men who let themselves be abused, the mendicant flatterers, and above all the liars:—it is a fundamental belief of all aristocrats that the common people are untruthful. “We truthful ones”—the nobility in ancient Greece called themselves. It is obvious that everywhere the designations of moral value were at first applied to MEN; and were only derivatively and at a later period applied to ACTIONS; it is a gross mistake, therefore, when historians of morals start with questions like, “Why have sympathetic actions been praised?”

The noble type of man regards HIMSELF as a determiner of values; he does not require to be approved of; he passes the judgment: “What is injurious to me is injurious in itself;” he knows that it is he himself only who confers honor on things; he is a CREATOR OF VALUES. He honors whatever he recognizes in himself: such morality equals self-glorification. In the foreground there is the feeling of plenitude, of power, which seeks to overflow, the happiness of high tension, the consciousness of a wealth which would fain give and bestow:—the noble man also helps the unfortunate, but not—or scarcely—out of pity, but rather from an impulse generated by the super-abundance of power. The noble man honors in himself the powerful one, him also who has power over himself, who knows how to speak and how to keep silence, who takes pleasure in subjecting himself to severity and hardness, and has reverence for all that is severe and hard. “Wotan placed a hard heart in my breast,” says an old Scandinavian Saga: it is thus rightly expressed from the soul of a proud Viking. Such a type of man is even proud of not being made for sympathy; the hero of the Saga therefore adds warningly: “He who has not a hard heart when young, will never have one.” The noble and brave who think thus are the furthest removed from the morality which sees precisely in sympathy, or in acting for the good of others, or in DESINTERESSEMENT, the characteristic of the moral; faith in oneself, pride in oneself, a radical enmity and irony towards “selflessness,” belong as definitely to noble morality, as do a careless scorn and precaution in presence of sympathy and the “warm heart.”

judgment: “What is injurious to me is injurious in itself;” he knows that it is he himself only who confers honor on things; he is a CREATOR OF VALUES. He honors whatever he recognizes in himself: such morality equals self-glorification. In the foreground there is the feeling of plenitude, of power, which seeks to overflow, the happiness of high tension, the consciousness of a wealth which would fain give and bestow:—the noble man also helps the unfortunate, but not—or scarcely—out of pity, but rather from an impulse generated by the super-abundance of power. The noble man honors in himself the powerful one, him also who has power over himself, who knows how to speak and how to keep silence, who takes pleasure in subjecting himself to severity and hardness, and has reverence for all that is severe and hard. “Wotan placed a hard heart in my breast,” says an old Scandinavian Saga: it is thus rightly expressed from the soul of a proud Viking. Such a type of man is even proud of not being made for sympathy; the hero of the Saga therefore adds warningly: “He who has not a hard heart when young, will never have one.” The noble and brave who think thus are the furthest removed from the morality which sees precisely in sympathy, or in acting for the good of others, or in DESINTERESSEMENT, the characteristic of the moral; faith in oneself, pride in oneself, a radical enmity and irony towards “selflessness,” belong as definitely to noble morality, as do a careless scorn and precaution in presence of sympathy and the “warm heart.”

—It is the powerful who KNOW how to honor, it is their art, their domain for invention. The profound reverence for age and for tradition—all law rests on this double reverence,—the belief and prejudice in favor of ancestors and unfavorable to newcomers, is typical in the morality of the powerful; and if, reversely, men of “modern ideas” believe almost instinctively in “progress” and the “future,” and are more and more lacking in respect for old age, the ignoble origin of these “ideas” has complacently betrayed itself thereby. A morality of the ruling class, however, is more especially foreign and irritating to present-day taste in the sternness of its principle that one has duties only to one’s equals; that one may act towards beings of a lower rank, towards all that is foreign, just as seems good to one, or “as the heart desires,” and in any case “beyond good and evil”: it is here that sympathy and similar sentiments can have a place. The ability and obligation to exercise prolonged gratitude and prolonged revenge—both only within the circle of equals,—artfulness in retaliation, RAFFINEMENT of the idea in friendship, a certain necessity to have enemies (as outlets for the emotions of envy, quarrelsomeness, arrogance—in fact, in order to be a good FRIEND): all these are typical characteristics of the noble morality, which, as has been pointed out, is not the morality of “modern ideas,” and is therefore at present difficult to realize, and also to unearth and disclose.

—It is otherwise with the second type of morality, SLAVE-MORALITY. Supposing that the abused, the oppressed, the suffering, the unemancipated, the weary, and those uncertain of themselves should moralize, what will be the common element in their moral estimates? Probably a pessimistic suspicion with regard to the entire situation of man will find expression, perhaps a condemnation of man, together with his situation.

The slave has an unfavorable eye for the virtues of the powerful; he has a skepticism and distrust, a REFINEMENT of distrust of everything “good” that is there honored—he would fain persuade himself that the very happiness there is not genuine. On the other hand, THOSE qualities which serve to alleviate the existence of sufferers are brought into prominence and flooded with light; it is here that sympathy, the kind, helping hand, the warm heart, patience, diligence, humility, and friendliness attain to honor; for here these are the most useful qualities, and almost the only means of supporting the burden of existence.

Slave-morality is essentially the morality of utility. Here is the seat of the origin of the famous antithesis “good” and “evil”:—power and dangerousness are assumed to reside in the evil, a certain dreadfulness, subtlety, and strength, which do not admit of being despised. According to slave-morality, therefore, the “evil” man arouses fear; according to master-morality, it is precisely the “good” man who arouses fear and seeks to arouse it, while the bad man is regarded as the despicable being. The contrast attains its maximum when, in accordance with the logical consequences of slave-morality, a shade of depreciation—it may be slight and well-intentioned—at last attaches itself to the “good” man of this morality; because, according to the servile mode of thought, the good man must in any case be the SAFE man: he is good-natured, easily deceived, perhaps a little stupid, un bonhomme.

Key Takeaway

Everywhere that slave-morality gains the ascendancy, language shows a tendency to approximate the significations of the words “good” and “stupid.“—A last fundamental difference: the desire for FREEDOM, the instinct for happiness and the refinements of the feeling of liberty belong as necessarily to slave-morals and morality, as artifice and enthusiasm in reverence and devotion are the regular symptoms of an aristocratic mode of thinking and estimating.—Hence we can understand without further detail why love AS A PASSION—it is our European specialty—must absolutely be of noble origin; as is well known, its invention is due to the Provencal poet-cavaliers, those brilliant, ingenious men of the “gai saber,” to whom Europe owes so much, and almost owes itself.

Everywhere that slave-morality gains the ascendancy, language shows a tendency to approximate the significations of the words “good” and “stupid.“—A last fundamental difference: the desire for FREEDOM, the instinct for happiness and the refinements of the feeling of liberty belong as necessarily to slave-morals and morality, as artifice and enthusiasm in reverence and devotion are the regular symptoms of an aristocratic mode of thinking and estimating.—Hence we can understand without further detail why love AS A PASSION—it is our European specialty—must absolutely be of noble origin; as is well known, its invention is due to the Provencal poet-cavaliers, those brilliant, ingenious men of the “gai saber,” to whom Europe owes so much, and almost owes itself.

…At the risk of displeasing innocent ears, I submit that egoism belongs to the essence of a noble soul, I mean the unalterable belief that to a being such as “we,” other beings must naturally be in subjection, and have to sacrifice themselves. The noble soul accepts the fact of his egoism without question, and also without consciousness of harshness, constraint, or arbitrariness therein, but rather as something that may have its basis in the primary law of things:—if he sought a designation for it he would say: “It is justice itself.”

He acknowledges under certain circumstances, which made him hesitate at first, that there are other equally privileged ones; as soon as he has settled this question of rank, he moves among those equals and equally privileged ones with the same assurance, as regards modesty and delicate respect, which he enjoys in intercourse with himself—in accordance with an innate heavenly mechanism which all the stars understand. It is an ADDITIONAL instance of his egoism, this artfulness and self-limitation in intercourse with his equals—every star is a similar egoist; he honors HIMSELF in them, and in the rights which he concedes to them, he has no doubt that the exchange of honors and rights, as the ESSENCE of all intercourse, belongs also to the natural condition of things. The noble soul gives as he takes, prompted by the passionate and sensitive instinct of requital, which is at the root of his nature. The notion of “favor” has, INTER PARES, neither significance nor good repute; there may be a sublime way of letting gifts as it were light upon one from above, and of drinking them thirstily like dew-drops; but for those arts and displays the noble soul has no aptitude. His egoism hinders him here: in general, he looks “aloft” unwillingly—he looks either FORWARD, horizontally and deliberately, or downwards—HE KNOWS THAT HE IS ON A HEIGHT.

He acknowledges under certain circumstances, which made him hesitate at first, that there are other equally privileged ones; as soon as he has settled this question of rank, he moves among those equals and equally privileged ones with the same assurance, as regards modesty and delicate respect, which he enjoys in intercourse with himself—in accordance with an innate heavenly mechanism which all the stars understand. It is an ADDITIONAL instance of his egoism, this artfulness and self-limitation in intercourse with his equals—every star is a similar egoist; he honors HIMSELF in them, and in the rights which he concedes to them, he has no doubt that the exchange of honors and rights, as the ESSENCE of all intercourse, belongs also to the natural condition of things. The noble soul gives as he takes, prompted by the passionate and sensitive instinct of requital, which is at the root of his nature. The notion of “favor” has, INTER PARES, neither significance nor good repute; there may be a sublime way of letting gifts as it were light upon one from above, and of drinking them thirstily like dew-drops; but for those arts and displays the noble soul has no aptitude. His egoism hinders him here: in general, he looks “aloft” unwillingly—he looks either FORWARD, horizontally and deliberately, or downwards—HE KNOWS THAT HE IS ON A HEIGHT.

…What is noble? What does the word “noble” still mean for us nowadays? How does the noble man betray himself, how is he recognized under this heavy overcast sky of the commencing plebeianism, by which everything is rendered opaque and leaden?—It is not his actions which establish his claim—actions are always ambiguous, always inscrutable; neither is it his “works.” One finds nowadays among artists and scholars plenty of those who betray by their works that a profound longing for nobleness impels them; but this very NEED of nobleness is radically different from the needs of the noble soul itself, and is in fact the eloquent and dangerous sign of the lack thereof.

It is not the works, but the BELIEF which is here decisive and determines the order of rank—to employ once more an old religious formula with a new and deeper meaning—it is some fundamental certainty which a noble soul has about itself, something which is not to be sought, is not to be found, and perhaps, also, is not to be lost.—THE NOBLE SOUL HAS REVERENCE FOR ITSELF.—

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Beyond Good and Evil, by Friedrich Nietzsche

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Beyond Good and Evil

Author: Friedrich Nietzsche

Translator: Helen Zimmern

Release Date: December 7, 2009 [EBook #4363]

Last Updated: February 4, 2013

Language: English

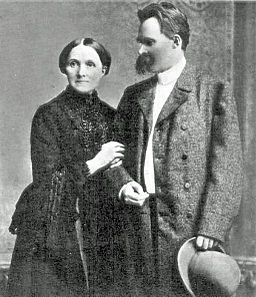

![Friedrich Nietzsche around 1869. Photo taken at studio Gebrüder Siebe, Leipzig. Then, he must have sent it to Deussen with his letter from July 1869 ([1], KGB II.1 No 10). A copy of this photography is at Goethe und Schillerarchiv, No. GSA 101/11](https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/194/2018/02/256px-Nietzsche187c-199x300.jpg)