15 Excerpts from the letters of Abelard and Héloïse

The Love Letters of Abelard and Heloise

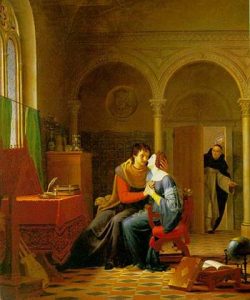

Both Abelard and Heloise were well known intellectuals from 12th century CE France. Abelard was a lecturer in philosophy. Heloise was an unusually well educated woman who spoke and read Latin, Greek and Hebrew. When Heloise was 19, she and Abelard fell in love, which was unfortunate, as he was her tutor at the time, and this caused a scandal. As a result of their affair, they had a child, Astrolabe, out of wedlock. When this situation was discovered by Heloise’s uncle, the uncle hired a man to assault and castrate Abelard, which was carried out successfully. Heloise was, after the birth of her child, forced to entered a convent. Abelard was exiled to Brittany, where he lived as monk. Heloise became abbess of the Oratory of the Paraclete, an abbey which Abelard had founded.

It was at this time that they exchanged their famous letters. It started when a letter from Abelard to another person falls into Heloise’s hands, where she reads his version of their love story. She finds that he is still suffering, and she knows that she has not found peace. So she writes to Abelard with passion and frustration and anger and despair; he replies in a letter that struggles between faith and equal passion. A short series of letters follow, and then there is nothing more that has survived of any more correspondence between the two.

Abelard died in 1142 CE at the age of sixty-three, and twenty years later Heloise died and was buried beside him. Abelard, although known at the time as a leader and philosopher, is only survived by his letters.

Heloise, the beautiful and the learned, is known merely as an example of the passionate devotion of a woman.

This story is part of a tale that focuses on the struggle to forget–to sink the love of the human in the love of the divine.

The letters are beautiful, and rather long. Here follow exerpts of key points from these beautiful letters.

Discussion of the types of love, the role of sexuality and relationship within religions, and the misuse of power from the clergy might be assisted through the reading of portions of the novel The Cloister, by James Carroll You can hear an interview with the author at PBS Frontline: Interview

You can listen to an interview with Jame Carroll at Boston WBUR about the novel The Cloister , but there is no transcript nor closed captions. Faith, History and the Catholic Church

We tarnish the lustre of our most beautiful actions when we applaud them ourselves. This is true, and yet there is a time when we may with decency commend ourselves; when we have to do with those whom base ingratitude has stupefied we cannot too much praise our own actions. Now if you were this sort of creature this would be a home reflection on you. Irresolute as I am I still love you, and yet I must hope for nothing. I have renounced life, and stript myself of everything, but I find I neither have nor can renounce my Abelard. Though I have lost my lover I still preserve my love. O vows! O convent! I have not lost my humanity under your inexorable discipline! You have not turned me to marble by changing my habit; my heart is not hardened by my imprisonment; I am still sensible to what has touched me, though, alas! I ought not to be! Without offending your commands permit a lover to exhort me to live in obedience to your rigorous rules. Your yoke will be lighter if that hand support me under it; your exercises will be pleasant if he show me their advantage. Retirement and solitude will no longer seem terrible if I may know that I still have a place in his memory. A heart which has loved as mine cannot soon be indifferent. We fluctuate long between love and hatred before we can arrive at tranquillity, and we always flatter ourselves with some forlorn hope that we shall not be utterly forgotten.

Yes, Abelard, I conjure you by the chains I bear here to ease the weight of them, and make them as agreeable as I would they were to me.

Teach me the maxims of Divine Love; since you have forsaken me I would glory in being wedded to Heaven. My heart adores that title and disdains any other; tell me how this Divine Love is nourished, how it works, how it purifies. When we were tossed on the ocean of the world we could hear of nothing but your verses, which published everywhere our joys and pleasures. Now we are in the haven of grace is it not fit you should discourse to me of this new happiness, and teach me everything that might heighten or improve it? Show me the same complaisance in my present condition as you did when we were in the world. Without changing the ardour of our affections let us change their objects; let us leave our songs and sing hymns; let us lift up our hearts to God and have no transports but for His glory!

I expect this from you as a thing you cannot refuse me. God has a peculiar right over the hearts of great men He has created. When He pleases to touch them He ravishes them, and lets them not speak nor breathe but for His glory. Till that moment of grace arrives, O think of me–do not forget me–remember my love and fidelity and constancy: love me as your mistress, cherish me as your child, your sister, your wife! Remember I still love you, and yet strive to avoid loving you. What a terrible saying is this! I shake with horror, and my heart revolts against what I say. I shall blot all my paper with tears. I end my long letter wishing you, if you desire it (would to Heaven I could!), for ever adieu!

Without growing severe to a passion that still possesses you, learn from your own misery to succour your weak sisters; pity them upon consideration of your own faults. And if any thoughts too natural should importune you, fly to the foot of the Cross and there beg for mercy–there are wounds open for healing; lament them before the dying Deity. At the head of a religious society be not a slave, and having rule over queens, begin to govern yourself. Blush at the least revolt of your senses. Remember that even at the foot of the altar we often sacrifice to lying spirits, and that no incense can be more agreeable to them than the earthly passion that still burns in the heart of a religious. If during your abode in the world your soul has acquired a habit of loving, feel it now no more save for Jesus Christ. Repent of all the moments of your life which you have wasted in the world and on pleasure; demand them of me, ’tis a robbery of which I am guilty; take courage and boldly reproach me with it.

I have been indeed your master, but it was only to teach sin. You call me your father; before I had any claim to the title, I deserved that of parricide. I am your brother, but it is the affinity of sin that brings me that distinction. I am called your husband, but it is after a public scandal. If you have abused the sanctity of so many holy terms in the superscription of your letter to do me honour and flatter your own passion, blot them out and replace them with those of murderer, villain and enemy, who has conspired against your honour, troubled your quiet, and betrayed your innocence. You would have perished through my means but for an extraordinary act of grace which, that you might be saved, has thrown me down in the middle of my course.

This is the thought you ought to have of a fugitive who desires to deprive you of the hope of ever seeing him again. But when love has once been sincere how difficult it is to determine to love no more! ’Tis a thousand times more easy to renounce the world than love. I hate this deceitful, faithless world; I think no more of it; but my wandering heart still eternally seeks you, and is filled with anguish at having lost you, in spite of all the powers of my reason. In the meantime, though I should be so cowardly as to retract what you have read, do not suffer me to offer myself to your thoughts save in this last fashion. Remember my last worldly endeavours were to seduce your heart; you perished by my means and I with you: the same waves swallowed us up. We waited for death with indifference, and the same death had carried us headlong to the same punishments. But Providence warded off the blow, and our shipwreck has thrown us into a haven. There are some whom God saves by suffering. Let my salvation be the fruit of your prayers; let me owe it to your tears and your exemplary holiness. Though my heart, Lord, be filled with the love of Thy creature, Thy hand can, when it pleases, empty me of all love save for Thee. To love Heloise truly is to leave her to that quiet which retirement and virtue afford. I have resolved it: this letter shall be my last fault. Adieu.

How dangerous it is for a great man to suffer himself to be moved by our sex! He ought from his infancy to be inured to insensibility of heart against all our charms. ‘Hearken, my son’ (said formerly the wisest of men), attend and keep my instructions; if a beautiful woman by her looks endeavour to entice thee, permit not thyself to be overcome by a corrupt inclination; reject the poison she offers, and follow not the paths she directs. Her house is the gate of destruction and death.’ I have long examined things, and have found that death is less dangerous than beauty. It is the shipwreckof liberty, a fatal snare, from which it is impossible ever to get free. It was a woman who threw down the first man from the glorious position in which Heaven had placed him; she, who was created to partake of his happiness, was the sole cause of his ruin. How bright had been the glory of Samson if his heart had been proof against the charms of Delilah, as against the weapons of the Philistines. A woman disarmed and betrayed he who had been a conqueror of armies. He saw himself delivered into the hands of his enemies; he was deprived of his eyes, those inlets of love into the soul; distracted and despairing he died without any consolation save that of including his enemies in his ruin. Solomon, that he might please women, forsook pleasing God; that king whose wisdom princes came from all parts to admire, he whom God had chosen to build the temple, abandoned the worship of the very altars he had raised, and proceeded to such a pitch of folly as even to burn incense to idols. Job had no enemy more cruel than his wife; what temptations did he not bear? The evil spirit who had declared himself his persecutor employed a woman as an instrument to shake his constancy. And the same evil spirit made Heloise an instrument to ruin Abelard. All the poor comfort I have is that I am not the voluntary cause of your misfortunes. I have not betrayed you; but my constancy and love have been destructive to you. If I have committed a crime in loving you so constantly I cannot repent it. I have endeavoured to please you even at the expense of my virtue, and therefore deserve the pains I feel.

In order to expiate a crime it is not sufficient to bear the punishment; whatever we suffer is of no avail if the passion still continues and the heart is filled with the same desire. It is an easy matter to confess a weakness, and inflict on ourselves some punishment, but it needs perfect power over our nature to extinguish the memory of pleasures, which by a loved habitude have gained possession of our minds. How many persons do we see who make an outward confession of their faults, yet, far from being in distress about them, take a new pleasure in relating them. Contrition of the heart ought to accompany the confession of the mouth, yet this very rarely happens.

All who are about me admire my virtue, but could their eyes penetrate, into my heart what would they not discover? My passions there are in rebellion; I preside over others but cannot rule myself. I have a false covering, and this seeming virtue is a real vice. Men judge me praiseworthy, but I am guilty before God; from His all-seeing eye nothing is hid, and He views through all their windings the secrets of the heart. I cannot escape His discovery. And yet it means great effort to me merely to maintain this appearance of virtue, so surely this troublesome hypocrisy is in some sort commendable. I give no scandal to the world which is so easy to take bad impressions; I do not shake the virtue of those feeble ones who are under my rule. With my heart full of the love of man, I teach them at least to love only God. Charmed with the pomp of worldly pleasures, I endeavour to show them that they are all vanity and deceit. I have just strength enough to conceal from them my longings, and I look upon that as a great effect of grace. If it is not enough to make me embrace virtue, ’tis enough to keep me from committing sin.

And yet it is in vain to try and separate these two things: they must be guilty who are not righteous, and they depart from virtue who delay to approach it. Besides, we ought to have no other motive than the love of God. Alas! what can I then hope for? I own to my confusion I fear more to offend a man than to provoke God, and I study less to please Him than to please you. Yes, it was your command only, and not a sincere vocation, which sent me into these cloisters.

You have not answered my last letter, and thanks to Heaven, in the condition I am now in it is a relief to me that you show so much insensibility for the passion which I betrayed. At last, Abelard, you have lost Heloise for ever.

Great God! shall Abelard possess my thoughts for ever? Can I never free myself from the chains of love? But perhaps I am unreasonably afraid; virtue directs all my acts and they are all subject to grace. Therefore fear not, Abelard; I have no longer those sentiments which being described in my letters have occasioned you so much trouble. I will no more endeavour, by the relation of those pleasures our passion gave us, to awaken any guilty fondness you may yet feel for me. I free you from all your oaths; forget the titles of lover and husband and keep only that of father. I expect no more from you than tender protestations and those letters so proper to feed the flame of love. I demand nothing of you but spiritual advice and wholesome discipline. The path of holiness, however thorny it be, will yet appear agreeable to me if I may but walk in your footsteps. You will always find me ready to follow you. I shall read with more pleasure the letters in which you shall describe the advantages of virtue than ever I did those in which you so artfully instilled the poison of passion. You cannot now be silent without a crime. When I was possessed with so violent a love, and pressed you so earnestly to write to me, how many letters did I send you before I could obtain one from you? You denied me in my misery the only comfort which was left me, because you thought it pernicious. You endeavoured by severities to force me to forget you, nor do I blame you; but now you have nothing to fear. This fortunate illness, with which Providence has chastised me for my good, has done what all human efforts and your cruelty in vain attempted. I see now the vanity of that happiness we had set our hearts upon, as if it were eternal. What fears, what distress have we not suffered for it!

No, Lord, there is no pleasure upon earth but that which virtue gives.

Write no more to me, Heloise, write no more to me; ’tis time to end communications which make our penances of nought avail. We retired from the world to purify ourselves, and, by a conduct directly contrary to Christian morality, we became odious to Jesus Christ. Let us no more deceive ourselves with remembrance of our past pleasures; we but make our lives troubled and spoil the sweets of solitude. Let us make good use of our austerities and no longer preserve the memories of our crimes amongst the severities of penance. Let a mortification of body and mind, a strict fasting, continual solitude, profound and holy meditations, and a sincere love of God succeed our former irregularities.

Let us try to carry religious perfection to its farthest point. It is beautiful to find Christian minds so disengaged from earth, from the creatures and themselves, that they seem to act independently of those bodies they are joined to, and to use them as their slaves. We can never raise ourselves to too great heights when God is our object. Be our efforts ever so great they will always come short of attaining that exalted Divinity which even our apprehension cannot reach. Let us act for God’s glory independent of the creatures or ourselves, paying no regard to our own desires or the opinions of others. Were we in this temper of mind, Heloise, I would willingly make my abode at the Paraclete, and by my earnest care for the house I have founded draw a thousand blessings on it. I would instruct it by my words and animate it by my example: I would watch over the lives of my Sisters, and would command nothing but what I myself would perform: I would direct you to pray, meditate, labour, and keep vows of silence; and I would myself pray, labour, meditate, and be silent.

I know everything is difficult in the beginning; but it is glorious to courageously start a great action, and glory increases proportionately as the difficulties are more considerable. We ought on this account to surmount bravely all obstacles which might hinder us in the practice of Christian virtue. In a monastery men are proved as gold in a furnace. No one can continue long there unless he bear worthily the yoke of the Lord.

Attempt to break those shameful chains which bind you to the flesh, and if by the assistance of grace you are so happy as to accomplish this, I entreat you to think of me in your prayers. Endeavour with all your strength to be the pattern of a perfect Christian; it is difficult, I confess, but not impossible; and I expect this beautiful triumph from your teachable disposition. If your first efforts prove weak do not give way to despair, for that would be cowardice; besides, I would have you know that you must necessarily take great pains, for you strive to conquer a terrible enemy, to extinguish a raging fire, to reduce to subjection your dearest affections. You have to fight against your own desires, so be not pressed down with the weight of your corrupt nature. You have to do with a cunning adversary who will use all means to seduce you; be always upon your guard. While we live we are exposed to temptations; this made a great saint say, ‘The life of man is one long temptation’: the devil, who never sleeps, walks continually around us in order to surprise us on some unguarded side, and enters into our soul in order to destroy it.![Pere Lachaise Cemetery. Tomb of Abelard and Heloise. Augustus Charles Pugin [Public domain or CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/194/2018/03/Haigh_-_Tomb_of_Abelard_and_Heloise_01.jpg)

Question not, Heloise, but you will hereafter apply yourself in good earnest to the business of your salvation; this ought to be your whole concern. Banish me, therefore, for ever from your heart–it is the best advice I can give you, for the remembrance of a person we have loved guiltily cannot but be hurtful, whatever advances we may have made in the way of virtue. When you have extirpated your unhappy inclination towards me, the practice of every virtue will become easy; and when at last your life is conformable to that of Christ, death will be desirable to you. Your soul will joyfully leave this body, and direct its flight to heaven. Then you will appear with confidence before your Saviour; you will not read your reprobation written in the judgment book, but you will hear your Saviour say, Come, partake of My glory, and enjoy the eternal reward I have appointed for those virtues you have practised.

Farewell, Heloise, this is the last advice of your dear Abelard; for the last time let me persuade you to follow the rules of the Gospel. Heaven grant that your heart, once so sensible of my love, may now yield to be directed by my zeal. May the idea of your loving Abelard, always present to your mind, be now changed into the image of Abelard truly penitent; and may you shed as many tears for your salvation as you have done for our misfortunes.

Written c. 1130-1140. Translated c. 1736 by John Hughes Letters of Abelard and Heloise

Edited by Israel Gollancz (English literary scholar; chair of English language and literature at King’s College, London) and Honnor Morten (1861-1913) in 1901.

![Abelard and his pupil Heloise by Edmund Leighton [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/194/2018/03/Edmund_Blair_Leighton_-_Abelard_and_his_Pupil_Heloise.jpg)

![Golden book of famous women, Londres : Hodder and Stoughton, 1919 Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/194/2018/03/Eloisa_and_Abelard-272x300.jpg)

![Condé Museum [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://mlpp.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/194/2018/03/Abelard_and_Heloise-226x300.jpeg)