Introduction

This workbook is for students and others who are learning GIS from the beginning. It is different from other introductory GIS workbooks in the following ways.

First, it is free. All contents are licensed Creative Commons, with the exception of some of the embedded graphics and multimedia. All graphics and multimedia were either created by the workbook author or used with permission of the original author; if copyrighted, the copyright notice is included in the caption. You may copy and share anything in the workbook that is not under copyright somewhere else.

Second, it does not specify datasets or project goals. Each chapter is structured to give you an introduction to a common set of tasks in GIS software, including what buttons and menu options to click to accomplish each task. The geographic data and scenarios you use for each task are up to your instructor, or you if you are working on your own. By not using canned datasets and projects, the hope is that the work you do for each chapter will be relevant to your local setting and more applicable to projects you may encounter in real life. If you are using this book on your own rather than for a class, you may find it a bit of a challenge to get together the data you need and create your own scenarios at first. You will have to be creative and maintain a problem-solving mindset. A list of good GIS data repositories is included in Appendix A.

Third, this workbook is not simply a step-by-step cookbook for getting to a certain outcome. I have found that when students who use other workbooks miss a step because of the book’s formatting, or encounter a feature that has changed in the software since the book was last updated, or even read a simple editing error, they often get stuck and wonder what to do next. The goal of this workbook is to challenge you to work through these problems by keeping in mind what you want to accomplish and what specific tasks you must do to get there. By learning this method, you should find it easier to transfer the skills you learn here to other settings and solve problems you encounter in real-world GIS work outside of the classroom.

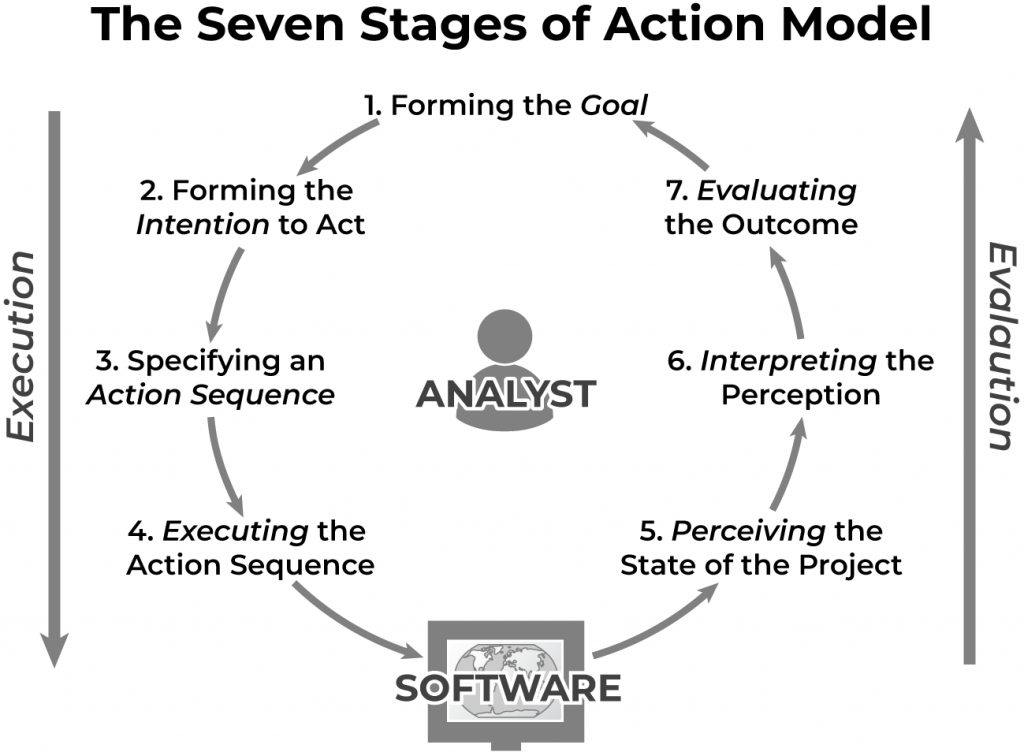

To that end, this book uses the Seven Stages of Action Model as a problem-solving framework. The Seven Stages of Action Model was created by Donald Norman, an expert in the field of usability studies, and detailed in his book The Design of Everyday Things. Norman sought to characterize how people think through an action and its results when working with everyday objects, such as a door or a light switch. The same model can easily be adapted to describe the situation of a geospatial analyst working in GIS software.

The first four stages of action can be grouped together as stages of execution. Execution means performing or doing something. When these stages have been accomplished, the GIS project is acted upon through the software that manages it. The final three stages of action are grouped together as stages of evaluation because they lead the analyst to determine how their action affected the project and whether it accomplished what they intended. The stages are:

Forming the Goal: The goal is what the analyst hopes to achieve by taking some action in the software. Goals can be very broad. An example of a GIS goal could be, “make a map of neighborhood fire hydrants.”

Forming the Goal: The goal is what the analyst hopes to achieve by taking some action in the software. Goals can be very broad. An example of a GIS goal could be, “make a map of neighborhood fire hydrants.” Forming the Intention to Act: An intention is a specific task that must be completed in order to achieve the goal. Intentions are narrower than goals. An example of an intention in GIS could be, “load fire hydrant point data into the project map.”

Forming the Intention to Act: An intention is a specific task that must be completed in order to achieve the goal. Intentions are narrower than goals. An example of an intention in GIS could be, “load fire hydrant point data into the project map.” Specifying an Action Sequence: An action sequence is a set of one or more concrete steps that must be taken in order to complete the action. An example of an action sequence in GIS could be, “click the Add Data button, navigate to the folder where the fire hydrant data is stored, select the desired dataset, and click the OK button.”

Specifying an Action Sequence: An action sequence is a set of one or more concrete steps that must be taken in order to complete the action. An example of an action sequence in GIS could be, “click the Add Data button, navigate to the folder where the fire hydrant data is stored, select the desired dataset, and click the OK button.” Executing the Action Sequence: Execution is actually performing the specified action sequence. An example of executing an action sequence in GIS would involve the analyst completing the steps specified in the example for Stage 3 to add the data to the project map.

Executing the Action Sequence: Execution is actually performing the specified action sequence. An example of executing an action sequence in GIS would involve the analyst completing the steps specified in the example for Stage 3 to add the data to the project map. Perceiving the State of the Project: Perceiving is identifying what happened as a result of an action. When an action is executed, the software may provide sensory feedback—such as a pop-up message or alert sound—that clues the analyst in to the results. The interface may also undergo a persistent change. An example of perceiving the state of a project in GIS would be noticing that a new point layer appears in the Table of Contents and new point symbols appear on the project map.

Perceiving the State of the Project: Perceiving is identifying what happened as a result of an action. When an action is executed, the software may provide sensory feedback—such as a pop-up message or alert sound—that clues the analyst in to the results. The interface may also undergo a persistent change. An example of perceiving the state of a project in GIS would be noticing that a new point layer appears in the Table of Contents and new point symbols appear on the project map. Interpreting the Perception: Once the analyst perceives what has changed in the project, they must then interpret those changes to actually determine what the results were. An example of interpreting the perception in GIS would be understanding that a layer of fire hydrant point data has now been added to the project Table of Contents and Map.

Interpreting the Perception: Once the analyst perceives what has changed in the project, they must then interpret those changes to actually determine what the results were. An example of interpreting the perception in GIS would be understanding that a layer of fire hydrant point data has now been added to the project Table of Contents and Map. Evaluating the Outcome: The final stage of the process occurs when the analyst evaluates whether the action satisfied the original intention and/or the overall goal, as well as the meaning of any unexpected results. An example of evaluating the outcome in GIS would be concluding that the intended fire hydrant dataset has indeed been loaded into the project map, and no further action is needed to satisfy that intention. However, the overall goal—“make a map of neighborhood fire hydrants”—may not yet be satisfied. In this case, the analyst must determine what to do next and start the process over again with the same goal but a different intention (e.g., “add fire hydrant symbols to the point locations of the hydrants”). The cycle continues until the goal is finally met.

Evaluating the Outcome: The final stage of the process occurs when the analyst evaluates whether the action satisfied the original intention and/or the overall goal, as well as the meaning of any unexpected results. An example of evaluating the outcome in GIS would be concluding that the intended fire hydrant dataset has indeed been loaded into the project map, and no further action is needed to satisfy that intention. However, the overall goal—“make a map of neighborhood fire hydrants”—may not yet be satisfied. In this case, the analyst must determine what to do next and start the process over again with the same goal but a different intention (e.g., “add fire hydrant symbols to the point locations of the hydrants”). The cycle continues until the goal is finally met.

While Norman created this model to improve the design of things, I am using it here for inverse purposes: to illuminate your thought processes as you navigate the existing GIS tools. For a GIS project to succeed, the actions you take must be intentional. They may result in an outcome you didn’t want or expect—that’s OK. In any technical field, you often learn by making mistakes and then correcting them. However, pushing buttons willy-nilly without understanding what you are doing does not help you master the skills you need to become an effective analyst. You must learn to take action intentionally and figure out what to do next when it works—and when it doesn’t.

The early chapters of this book will walk you through each stage of an action sequence while you perform it in the software, in general terms. You will be asked to restate each stage and fill in the details for your specific project. As you progress through the book, you will increasingly describe the stages yourself, so you get used to thinking through what you are doing.

This brings me to the final point of this Introduction, which is that the skills and procedures presented in this workbook are worthless in a conceptual vacuum. An understanding of geographic information science is critical to successful use of geographic information systems. This workbook is not a standalone textbook; rather, it is intended as a companion to the open textbook Essentials of Geographic Information Systems by Jonathan Campbell and Michael Shin (2011), available from the University of Minnesota Open Textbook Library. You will see references to various terms, concepts, and sections from that textbook throughout this workbook.

With all that in mind, let’s get rolling.

Introduction References

Norman, Donald. 1988. The Design of Everyday Things. New York: Basic Books.

Roth, Robert E. 2012. “Cartographic Interaction Primitives: Framework and Synthesis.” The Cartographic Journal 49(4), 376-395. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743277412Y.0000000019

Wikipedia Contributors. 2020. “Seven stages of action.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Online: Accessed June 9, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seven_stages_of_action

A cognitive model of how people interact with an object to achieve a desired goal.