Libraries and Learning

When is the Library Open: PS

June 9, 2016

It must be the season for books by librarians about libraries. I have two on my review pile and saw the IHE story about David Lankes’ new book, a field guide to what he calls “new librarianship” to accompany his atlas. It’s interesting how many books are published by librarians who urge us to decouple the image of books on shelves from the idea of the library. In contrast, a non-librarian, Mirela Roncevic, recently wrote an essay begging librarians to pay more attention to promoting books and reading rather than outreach and developing new programs.

You won’t find many librarians making that argument these days, though you will find quiet and stubborn resistance to providing people and funding to actually do the trendy things we’re all supposed to be doing like digital scholarship support, data management, learning analytics, developing open education resources, providing publishing support, and being the local experts at altmetrics. The things we find old-fashioned and slightly embarrassing still have enormous gravitational pull.

It’s a weird situation. We won’t go on record to say we care about books or that we’re fine with paying big publishers big bucks to license big deals because that would be incredibly uncool, but much of our staffing and most of our financial resources go to those things. Redirecting money and staff time from licensed databases to supporting open access projects is hard even if these things have been on ACRL’s annual Top Trends list for years.

What really got me thinking, though, was Lankes’ argument that librarians should be more integrated into the tenure process by providing support for altmetrics. We certainly could do that – and Robin Chin Roemer and Rachel Borchardt have written a how-to (and why-to) manual on that very subject for librarians. But I have a real problem with our metrics obsession, our belief that productivity in the form of publication is the most important measure by which academics should be judged.

I think open access to knowledge is really important. I think librarians need to be actively involved in making it happen in a way that doesn’t continue to privilege those with resources enough to play the game. In other words, I don’t want Elsevier and its cousins to make open access simply a new revenue model. But one issue that gets left out of most open access debates is whether we’re actually publishing too much and for all the wrong reasons. Mostly what I hear is “if you publish openly you can reach more people and collect more badges and show how productive you are!”

When did the word “productivity” enter the academic lexicon? Why have we embraced it so uncritically?

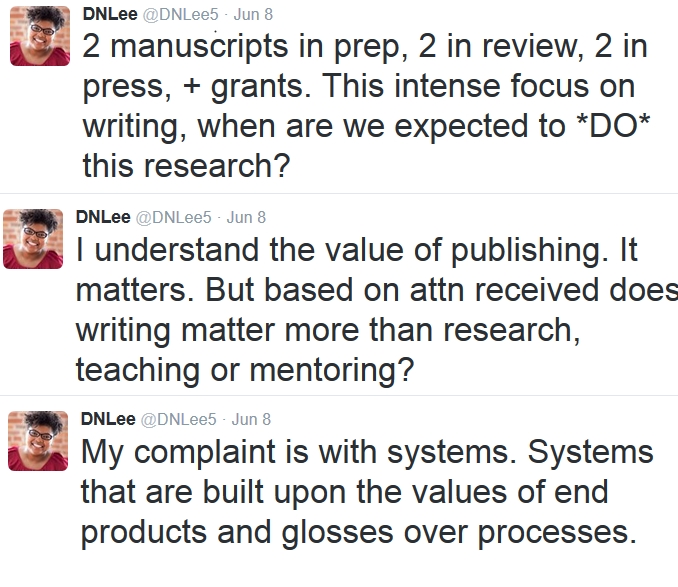

Some tweets from scientist and blogger Danielle N. Lee really put this in perspective for me. The entire rant was a thing of beauty, but these excerpts will give you the gist.

So in reply, and as an addendum to last week’s post urging librarians to take on the cause of open access before the big corporations own in completely, I would like to add: let’s publish in the open, but let’s also critique the anxieties that drive the amount of publishing we’re requiring of each other. Let’s encourage the entire process of research, including daydreaming and chatting and reading and fieldwork and bench science, not just publication of research results. Let’s make sure we give one another time to think and give our research its own time to gestate. Let’s think about sustainability not just in terms of how we’ll budget for open access but in terms of the human beings who do research.

I’ve preached this gospel before, but I’m adding it as a PS to my open access argument because the right to access information is important but so is the right to do meaningful research at a reasonable and humane pace. Our research – and the world it serves – will be better for it. This high-stakes productivity nonsense is destructive.