Libraries and Learning

This Is Why We Can Have Nice Things

(A talk given at a symposium, Libraries in the Context of Capitalism, held at METRO New York, February 1, 2018.)

I’ve been thinking a lot about how what libraries do every day runs completely counter to the belief systems underpinning late capitalism, so I’m really looking forward to the conversations we’ll have over the next two days about where we are in our communities, how we teach, how we can avoid reproducing capitalism, what John Kenneth Galbraith told us, how we can change publishing and critique our academic rewards system, how our labor is undervalued, how to organize, and finally, how to hope.

What I’ll talk about this afternoon is the radical possibility of libraries and the ways in which the values we’ve developed over the decades could guide resistance to capitalist assumptions and agitate for change in our broader information landscape. I want to look back at how American libraries, especially public libraries, became an everyday fixture of communities, how our values evolved, and what we thought the future would hold – seeing how libraries have continually interacted with, adopted, and at the same time resisted capitalism.

In so many ways our libraries have been captured by capitalism despite our lofty values, ideals shrouded in the “vocational awe” that Fobazi Ettarh recently wrote about, which prevents us being uncritical of our profession and its operations because it’s untouchably idealistic. There’s a gap between what we do and what we claim to do because we constantly make concessions, exchanging ideals for other perceived needs. For example, we might agree to “demonstrate our value” in terms that violate the privacy we purport to defend because we fear what might happen if we aren’t valued. We want to teach critical information literacy but so often acquiesce to training students to be students rather than free human beings because being liberated has less practical value and because we worry our students will be kicked out if they don’t know the ropes. We aren’t reflective enough about the concessions we make, and we may not even notice we’re making them.

But what interests me more than what we do wrong is that libraries ought not to be allowed to exist at all. The very idea of a library runs counter to all of the principles underpinning our dominant understanding of human society. In the capitalist view, humans are individual entities motivated by self-interest and the market is not just the best mechanism for social regulation but is actually synonymous with “liberty” because it gives us freedom to want things (though not freedom from want). An entity like Google can organize the world’s information – of course! It’s a business. It produces wealth. Shareholders are rewarded. It doesn’t need any further justification. But libraries? How can we justify taking tax dollars to create spaces where freeloaders can spend time without having to pay for the privilege? What excuse do we have for organizing the collective sharing of intellectual property? How is that even legal? Yet, here we are. We may feel underfunded, underappreciated, under threat. But unlike most social institutions these days, we’re not under constant attack for simply existing.

One of the paradoxes of libraries is that they are well liked across all ages, classes, and political affiliations. In part, that’s because we are disguised as traditional and orderly community establishments that threaten nobody and uphold local values – all of them, across the board, even when they are in conflict. Unlike our public schools, libraries haven’t been forced to compete against one another for resources, haven’t been resegregated, and haven’t been handed over to the private sector to be managed properly. (Though cities could outsource their library operations to LSSI, a for-profit corporation, very few have done so. Of over 9,000 public library systems in the country, only 19 are outsourced to LSSI – and this is after claiming to be the future, for two decades.) Unlike our universities, libraries haven’t been widely criticized for elitism and indoctrination, nor have they been forced to fund themselves by requiring users to take on debt for expensive entrance fees. There is no other social institution that has so thoroughly escaped the tendency, cultivated since before the Reagan presidency, to believe government is the problem and private enterprise is the solution. There is no other community site other than, perhaps, city parks where the right and the left, the old and the young, the wealthy and the homeless can feel “this is mine. I belong here.” Libraries are generally seen as a good thing if not a harmless anachronism, but in spite of their benign image they embody a mission that by today’s standards is radical.

One of the paradoxes of libraries is that they are well liked across all ages, classes, and political affiliations. In part, that’s because we are disguised as traditional and orderly community establishments that threaten nobody and uphold local values – all of them, across the board, even when they are in conflict. Unlike our public schools, libraries haven’t been forced to compete against one another for resources, haven’t been resegregated, and haven’t been handed over to the private sector to be managed properly. (Though cities could outsource their library operations to LSSI, a for-profit corporation, very few have done so. Of over 9,000 public library systems in the country, only 19 are outsourced to LSSI – and this is after claiming to be the future, for two decades.) Unlike our universities, libraries haven’t been widely criticized for elitism and indoctrination, nor have they been forced to fund themselves by requiring users to take on debt for expensive entrance fees. There is no other social institution that has so thoroughly escaped the tendency, cultivated since before the Reagan presidency, to believe government is the problem and private enterprise is the solution. There is no other community site other than, perhaps, city parks where the right and the left, the old and the young, the wealthy and the homeless can feel “this is mine. I belong here.” Libraries are generally seen as a good thing if not a harmless anachronism, but in spite of their benign image they embody a mission that by today’s standards is radical.

At their best, librarians encourage public funding for resources held in common. They advocate for unlimited access for all to advance knowledge and the common good. They create programs to address community issues and needs. They provide lifelong learning opportunities and encourage a democracy of thought and culture. They help students learn how to find information and recognize propaganda while encouraging them to find their own voices as citizens who have the power to shape the world. And librarians, at least in the public arena, strive to ensure that all of these things are available to every single member of their community, regardless of age, income, gender, ethnicity, ability, or social standing.

These values, bundled up in a traditional and seemingly unthreatening package, present a powerful antidote to the market fundamentalism that has thoroughly infiltrated tech culture, the information industries, our political discourse, and the public sphere in recent decades. Though lord knows libraries have never been immune from systems of social injustice or the influence of market-based economic philosophies, their very existence reminds us that, as a society, we have the capacity and the will to establish community-owned platforms for the public good rather than for profit, that it’s possible to nurture civic conversations that can open the borders between polarized groups, that knowledge is best treated as a common good rather than corporate property, and that sharing need not be paid for by revealing every detail of your personal life to data miners. Another world is possible. In fact, there’s a model of it just down the street.

These values, bundled up in a traditional and seemingly unthreatening package, present a powerful antidote to the market fundamentalism that has thoroughly infiltrated tech culture, the information industries, our political discourse, and the public sphere in recent decades. Though lord knows libraries have never been immune from systems of social injustice or the influence of market-based economic philosophies, their very existence reminds us that, as a society, we have the capacity and the will to establish community-owned platforms for the public good rather than for profit, that it’s possible to nurture civic conversations that can open the borders between polarized groups, that knowledge is best treated as a common good rather than corporate property, and that sharing need not be paid for by revealing every detail of your personal life to data miners. Another world is possible. In fact, there’s a model of it just down the street.

This should be impossible. We live in a world increasingly marked by precarious employment, disproportionate power held by monopolies, wealth concentrated at the top, and relationships within our communities unraveling as our nation becomes more diverse. In short, it’s an era remarkably similar to the decades during which American public libraries first took root and began to spread, eventually becoming a common feature of most communities.

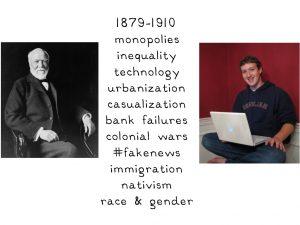

There are so many parallels. During the Gilded Age, large corporations owned by the super-rich had gained the power to shape society and fundamentally change the lives of ordinary people. New communication technologies, industrial processes, and data-driven management methods combined to draw workers into deskilled jobs. Laborers who once could take pride in their trade lost the sense of agency as they became cogs in a Tayloristic machine that treated workers as interchangeable parts. There were more consumer goods on the market but prosperity was an illusion for the majority. Mass layoffs were common. Workers who organized were violently rebuffed by state actors and business interests working in concert. Large companies grew even larger through merge rs and industry consolidation. The state engaged in wars supported by false and hyped media reports. Panics driven by dubious global financial dealings and bank failures were followed by years of economic depression. The gap between rich and poor grew, with unprecedented levels of wealth concentrated among a tiny percentage of the population.

rs and industry consolidation. The state engaged in wars supported by false and hyped media reports. Panics driven by dubious global financial dealings and bank failures were followed by years of economic depression. The gap between rich and poor grew, with unprecedented levels of wealth concentrated among a tiny percentage of the population.

The changes weren’t all economic. Gender roles were being redefined as women began to live and work independently. A wave of immigration changed national demographics. Native-born whites felt threatened, prompting a nativist backlash. Immigrants weren’t the only victims of white rage. During this era, the hard-won rights of emancipated African Americans were systematically rolled back through voter suppression, widespread acts of terror, and the enactment of a punitive legal system. Indigenous people faced broken treaties, seized land, military suppression, and forced assimilation.

It all sounds very familiar. But it was out of this froth of conflict and division that the idea of the American public library, a publicly-supported cultural institution that would be free to all members of the community, emerged to become an uncontroversial staple of community life. How did that happen? And how did we come by our core values?

In the mid-nineteenth century, the idea of providing libraries to the public was embraced by wealthy men, the Bill Gates of their day, who used their philanthropy to stamp their good works with a particular world view, one that included those contradictions we still experience. The library was to be Free to All and dedicated to the Advancement of Learning – our core values of access to information and lifelong learning have deep roots – but that civilizing mission was intended to enhance the workforce, mold new Americans to a common culture and to ensure public order. Large urban public library buildings carried ambiguous messages : ordinary people were as deserving as anyone to have sumptuous surroundings, but they had to accept the library’s civilizing mission, which at first included limited opening hours, closed stacks, and highly curated reading materials designed to foster a singular American identity.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the idea of providing libraries to the public was embraced by wealthy men, the Bill Gates of their day, who used their philanthropy to stamp their good works with a particular world view, one that included those contradictions we still experience. The library was to be Free to All and dedicated to the Advancement of Learning – our core values of access to information and lifelong learning have deep roots – but that civilizing mission was intended to enhance the workforce, mold new Americans to a common culture and to ensure public order. Large urban public library buildings carried ambiguous messages : ordinary people were as deserving as anyone to have sumptuous surroundings, but they had to accept the library’s civilizing mission, which at first included limited opening hours, closed stacks, and highly curated reading materials designed to foster a singular American identity.

The Gilded Age figure most frequently associated with American public libraries is Andrew Carnegie. Between 1887 and 1917, about half of the public libraries built in the United States were partially funded by his philanthropy. Like today’s Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, Carnegie believed his fortune was entirely the result of his work ethic and superior intelligence. In “The Gospel of Wealth” he argued the superiority of the self-made mega-rich endowed them uniquely with the capacity to make wise decisions for the deserving poor. (Sound familiar?)

Carnegie rejected the grandeur of palatial public buildings as excessive and indulgent, focusing much of philanthropy on utilitarian branch libraries in urban neighborhoods and small towns where the closest thing to elites were middle-class businessmen. (Though he intended these libraries to be free to all, he made exceptions in the south, where African Americans were not permitted to use the libraries their taxes paid for, though he funded a small handful of “colored branches.”) His project was designed to operate on an industrial scale, establishing libraries throughout the country using a common set of designs, standards and processes. This business focus aligned with our early library “thought leaders.” In 1897 John Cotton Dana argued libraries should reject fashioning themselves as a temple, a cathedral, or a “mortuary pile” but rather should be modeled on “the workshop, the factory, the office building.” (He also described a book vending machine – probably in jest.) In 1901 Melvil Dewey suggested that as cheap as books had become, within 25 years academic libraries would encourage students to “cut up books freely for notes and scraps.” I’ve often thought we are too quick to make our library websites look and act like shopping platforms, but I didn’t realize this urge to commodify information for individual use went so far back. Then again, the ALA’s original motto sounds like a prospectus for outsourcing: “the best reading for the greatest number at the least cost” – adopted in 1892 and (curiously) reinstated in 1988 during the twilight of the Reagan administration.

Carnegie’s grants overlapped with a progressive impulse to bring opportunities to poor and working class citizens. These disparate motivations fueled the founding of libraries that provided access to books and to reading rooms and to a variety of social and cultural programs, including English lessons for immigrants, folk dancing classes, art exhibits, public lectures, and children’s programming – often prefaced by lessons in “hygiene” requiring kids to wash their hands before touching the books. Ever since we’ve seen libraries try to accommodate two conflicting goals: providing utilitarian value (preparing a workforce or enabling an individual’s personal growth) and a sense of social responsibility (addressing civic issues, creating a welcoming community space for all). These aren’t always in conflict, but they can be if we don’t pay attention.

Though Carnegie is given credit for the growth of public libraries it was women who really made it happen. Women’s clubs eventually were responsible for starting as many as three-quarters of the nation’s public libraries. They could get away with it because socially progressive work was aligned with the Victorian notion that men and women inhabited different spheres appropriate for their sexes. Commerce, politics, and waging war were the domain of men; women’s work was with the family and in the home. As “new women” – women with college degrees and ambitions – began to have careers, their domestic sphere of influence expanded, but only so far. Jobs that involved promoting culture, social welfare, and the care of children – education, nursing, social work, and librarianship -offered women the chance to do paid work in public venues that didn’t violate the boundaries of the male sphere but gave women meaningful roles in shaping society, sometimes in subversive ways.

Though Carnegie is given credit for the growth of public libraries it was women who really made it happen. Women’s clubs eventually were responsible for starting as many as three-quarters of the nation’s public libraries. They could get away with it because socially progressive work was aligned with the Victorian notion that men and women inhabited different spheres appropriate for their sexes. Commerce, politics, and waging war were the domain of men; women’s work was with the family and in the home. As “new women” – women with college degrees and ambitions – began to have careers, their domestic sphere of influence expanded, but only so far. Jobs that involved promoting culture, social welfare, and the care of children – education, nursing, social work, and librarianship -offered women the chance to do paid work in public venues that didn’t violate the boundaries of the male sphere but gave women meaningful roles in shaping society, sometimes in subversive ways.

Public libraries developed their values in parallel to the Settlement Movement, also led by women, shifting from cultural uplift to becoming neighborhood-based social centers. This was also a function of the WPA library programs during the Great Depression, which employed over 14,000 people, built over 200 libraries, and funded programs such as the packhorse librarians who took books into the Kentucky mountains where there were no libraries.

Public libraries developed their values in parallel to the Settlement Movement, also led by women, shifting from cultural uplift to becoming neighborhood-based social centers. This was also a function of the WPA library programs during the Great Depression, which employed over 14,000 people, built over 200 libraries, and funded programs such as the packhorse librarians who took books into the Kentucky mountains where there were no libraries. Intellectual freedom was not a publicly-voiced value in the early decades. In fact librarians often thought their job was to guide readers, which meant censoring reading that was not “improving.” Many public libraries kept dangerous books in a special area called “the inferno” or “purgatory.” I briefly worked at a public library in Kentucky and remember finding an old shelf list card that listed a book’s location as “in the closet.” Library directors bragged about discouraging the reading of fiction. That changed as the people made clear they wanted a greater democracy of reading tastes represented in their libraries. Perhaps that prepared the ALA to adopt the Library Bill of Rights in 1939. It’s worth remembering that the U.S. was not uniformly opposed to fascism in the 1930s, which shouldn’t be surprising since our racist laws inspired Nazism. In that context, this statement supporting access to a wide variety of viewpoints and opposing censorship was a step forward. The Freedom to Read statement affirmed this stance in 1952 during Joe McCarthy’s anti-communism campaign. Though we look back on this period with shame, McCarthy was a pretty popular figure – in 1954 a Gallup poll found half of Americans had a favorable opinion of him – so this wasn’t necessarily an easy position to take.

Intellectual freedom was not a publicly-voiced value in the early decades. In fact librarians often thought their job was to guide readers, which meant censoring reading that was not “improving.” Many public libraries kept dangerous books in a special area called “the inferno” or “purgatory.” I briefly worked at a public library in Kentucky and remember finding an old shelf list card that listed a book’s location as “in the closet.” Library directors bragged about discouraging the reading of fiction. That changed as the people made clear they wanted a greater democracy of reading tastes represented in their libraries. Perhaps that prepared the ALA to adopt the Library Bill of Rights in 1939. It’s worth remembering that the U.S. was not uniformly opposed to fascism in the 1930s, which shouldn’t be surprising since our racist laws inspired Nazism. In that context, this statement supporting access to a wide variety of viewpoints and opposing censorship was a step forward. The Freedom to Read statement affirmed this stance in 1952 during Joe McCarthy’s anti-communism campaign. Though we look back on this period with shame, McCarthy was a pretty popular figure – in 1954 a Gallup poll found half of Americans had a favorable opinion of him – so this wasn’t necessarily an easy position to take.

And it wasn’t an obvious stance given the findings of a massive study commissioned by the ALA to study the purpose and effectiveness of public libraries. Led by social scientists, the Public Library Inquiry asked “How effective is the public library in cultivating intelligent loyalty to the basic conceptions and ideals of the democratic way of life?” It concluded it was failing. Not enough people used the library, and they weren’t the right people reading the right books. The authors recommended libraries double down on their educational mission and remain technically free to all while concentrating on providing useful information to opinion leaders and do more to support business. If that was the future of libraries, the people weren’t having it, and neither in the long run were librarians.

And it wasn’t an obvious stance given the findings of a massive study commissioned by the ALA to study the purpose and effectiveness of public libraries. Led by social scientists, the Public Library Inquiry asked “How effective is the public library in cultivating intelligent loyalty to the basic conceptions and ideals of the democratic way of life?” It concluded it was failing. Not enough people used the library, and they weren’t the right people reading the right books. The authors recommended libraries double down on their educational mission and remain technically free to all while concentrating on providing useful information to opinion leaders and do more to support business. If that was the future of libraries, the people weren’t having it, and neither in the long run were librarians.

In the 1960s libraries fared well with new federal funding. Editorial Research Reports profiled the growth of libraries, opening with “The library, that once quiet refuge of children, old folks, and a small band of scholars, has become as busy as the local supermarket.” But funding soon tapered off. The election of Ronald Reagan announced the importance of private enterprise over public services. Libraries experimented with charging for services , but the ALA resisted. In 1993, the association adopted a statement on economic barriers to information access, saying libraries should “resist the temptation to impose user fees to alleviate financial pressures, at long-term cost to institutional integrity and public confidence in libraries.”

In the 1960s libraries fared well with new federal funding. Editorial Research Reports profiled the growth of libraries, opening with “The library, that once quiet refuge of children, old folks, and a small band of scholars, has become as busy as the local supermarket.” But funding soon tapered off. The election of Ronald Reagan announced the importance of private enterprise over public services. Libraries experimented with charging for services , but the ALA resisted. In 1993, the association adopted a statement on economic barriers to information access, saying libraries should “resist the temptation to impose user fees to alleviate financial pressures, at long-term cost to institutional integrity and public confidence in libraries.”

In the late 1990s many librarians were certain our patrons were abandoning libraries because Barnes & Nobles was so much nicer. This drove a wave of “merchandizing” libraries which led to some good things – more attention to comfortable seating, inviting book displays, and accepting that people could drink coffee in a library – but also led to public librarians calling patrons “customers” which alters the relationship of the library to the public it serves.

The rise of technology as the millennium approached caused a second wave of panic – what if people got information without our help? – which prompted the adoption of a statement titled “Libraries: an American Value.” It affirmed he importance of libraries for democracy in a digital age and encouraged libraries to serve the whole community in all of its diversity. A few years later, after the 9/11 attacks, the association passed a resolution opposing the suppression of access to government information and “the misuse of governmental power to intimidate, suppress, coerce, or compel speech.” This, of course, was the moment when the FBI complained of “hysterical librarians” leading the charge against a burgeoning surveillance state. We fall short on privacy in many ways, but we know better, and we’re at least talking about these conflicts when few information professionals are.

Let’s switch over to the rise of tech culture at this point, because things were in play that would lead to “Google” becoming a verb and “share” would take on a new meaning altogether. What has happened makes a case that library values are more needed than ever – and not just in libraries.

Let’s switch over to the rise of tech culture at this point, because things were in play that would lead to “Google” becoming a verb and “share” would take on a new meaning altogether. What has happened makes a case that library values are more needed than ever – and not just in libraries.

We can see the roots of tech culture in the 1996 “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” in which John Perry Barlow argued that governments, which are by definition tyrannical, have no jurisdiction over cyberspace, which arose sui generis, without public investment. Here is the idealized notion of the internet as a place of freedom and equality and a libertarian faith that people will get along so long as there are no rules.

We are creating a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity . . . We believe that from ethics, enlightened self-interest, and the commonweal, our governance will emerge.

We all know how that’s turned out. Right from the start, freedom on the internet has been defined as “freedom to,” not “freedom from” and while it’s not stated, there’s a sense that everyone has the same opportunities, that meritocracy actually exists. Barlow also didn’t anticipate the evolution of the internet into a shopping and streaming platform with surveillance hardwired in.

Remember the hype around Web 2.0? This rebooted version of the web would give everyone a chance to participate in a vibrant, democratic conversation enabled by sites that had sharing and social capabilities baked in. The hacker ethic Barlow approved of – an ethic of making and sharing things in a decentralized, open online society – was folded into a world view in which capitalism, freed of government regulation and outdated management practices, would allow a new meritocracy of young (mostly white, mostly male) entrepreneurs to radically change society because they could. This hubris is how Ben Huh, who made a fortune turning I Can Haz Cheezburger into a media empire can launch himself into the work of creating new cities from scratch because, well, who needs expertise when you turned LOLCats into money? It’s a twenty-first century version of Andrew Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth.” Not only is wealth a sign of superiority, it gives the anointed few the opportunity to make decisions for the rest of us. What we call the “tech industry” is really just entrepreneurs with buckets of venture capital using the advantages they have to dominate markets by casualizing labor and evading regulations, standards, and social norms.

Where things get especially spooky is in the rise of surveillance capitalism. The development of “big data” means information can be gathered in real time, in enormous amounts, with fine granularity, and processed quickly, enabling things we never dreamed of before we have a chance to say “no.” We went, innocently enough, into Web 2.0 without realizing what was happening at the back end. Paying for a free platform with a few ads seemed a fair tradeoff. Nobody mentioned we were enabling lifelong, ubiquitous datamining. This developed in step with state surveillance. Even immediately after 9/11, people rejected a government program to combine data sources for its “total information awareness” program as too invasive, too Big Brother. That surveillance became strangely more acceptable or at least inevitable after Facebook launched and we got used to being watched while being coaxed to self-market.

Where things get especially spooky is in the rise of surveillance capitalism. The development of “big data” means information can be gathered in real time, in enormous amounts, with fine granularity, and processed quickly, enabling things we never dreamed of before we have a chance to say “no.” We went, innocently enough, into Web 2.0 without realizing what was happening at the back end. Paying for a free platform with a few ads seemed a fair tradeoff. Nobody mentioned we were enabling lifelong, ubiquitous datamining. This developed in step with state surveillance. Even immediately after 9/11, people rejected a government program to combine data sources for its “total information awareness” program as too invasive, too Big Brother. That surveillance became strangely more acceptable or at least inevitable after Facebook launched and we got used to being watched while being coaxed to self-market.

With artificial intelligence, the data industry is getting a new level of control. A company gathers license-plate location data and sells it to local police and now to ICE, mapping people’s travels and predicting when and where they can be arrested. Algorithms are use do decide who gets a loan, a job, or a prison sentence. Companies and the state can identify our faces, our voices, our gait, and they can tell where we are and who we associate with while making assumptions about us based on behavioral data. All of this is being done without accountability, without auditing, without necessarily learning from mistakes, because it’s a trade secret.

These systems have a high error rate and have bias baked in. They can also be manipulated, and not just for political purposes. Some guy on Reddit has been sharing instructions on how to put any woman’s face onto bodies in porn videos. Zeynep Tufekci has said “we’re building a dystopia just to make people click on ads,” which to some extent is true. Facebook, Twitter, and Google seem as shallow as John Perry Barlow in their understanding of society and are shocked, shocked when their plans to make the world better are derailed by naughty behavior. But this dystopia is also built on the vacuum left when there is no ethical basis for a company or a state’s actions other than innovation, growth, power, and profit.

Back in the day, Carnegie had a selfish interest in building a better workforce and a more stable society through libraries, confident he was positioned to decide what was good for society. But he built public support for libraries into his plans, knowing that reliance on gifts and volunteerism wouldn’t be sustainable. Local control over those libraries and the evolution of values in our profession over 150 years have given librarians a perspective that needs to be applied to our entire information environment. Let’s ask hard questions. Let’s promote our values as guideposts for this terrible bind we’re in before it’s too late. Let’s take this message beyond our libraries.

I’m not saying librarians are exceptional. Like most people, we don’t live up to our aspirations. We value diversity, but can’t seem to figure out how to welcome people of color into a profession that is 87 percent white. We value privacy but allow Amazon to track readers who borrow library-licensed ebooks and we put social media links on our websites, which serve as surveillance beacons for Facebook and Twitter. We value access to knowledge for all, but librarians who feel proud of creating well-equipped maker spaces with the latest in 3-D printers may not give much thought to residents in a neighboring community where the library can only afford a half-dozen aging computers. We’re myopic, focused on local communities, but fail at thinking collectively. Librarians, no matter how forward-thinking or community-oriented, won’t change the world by ourselves. What could save us is seeing, on an everyday basis, that another world is possible and already exists in small pockets of hope just down the street, a small-scale proof of concept model for a better world.

The idea of the public library was built on the optimistic belief that people are curious and socially responsible, able to make up their minds provided they have the liberty to explore a wide range of ideas and viewpoints without interference from autocrats or algorithms. People have proven they are willing to pay their fair share to make this experience available to all, at least at the local community level. Over more than a century, librarians have developed a set of guiding values that stand in stark contrast to the assumption that markets know best and freedom is just another word for consumer choice. Providing equal access to knowledge, standing up for intellectual freedom, protecting privacy, promoting diversity, democracy, social responsibility, and the value of the public good over private interests – these values scaled up could go a long way toward changing our troubled world for the better. What libraries do every day is a statement of faith that we can, together, create a more just and equal society.

The idea of the public library was built on the optimistic belief that people are curious and socially responsible, able to make up their minds provided they have the liberty to explore a wide range of ideas and viewpoints without interference from autocrats or algorithms. People have proven they are willing to pay their fair share to make this experience available to all, at least at the local community level. Over more than a century, librarians have developed a set of guiding values that stand in stark contrast to the assumption that markets know best and freedom is just another word for consumer choice. Providing equal access to knowledge, standing up for intellectual freedom, protecting privacy, promoting diversity, democracy, social responsibility, and the value of the public good over private interests – these values scaled up could go a long way toward changing our troubled world for the better. What libraries do every day is a statement of faith that we can, together, create a more just and equal society.

How would this actually play out? I’m hoping the rest of this conference will help me figure out some practical steps to take and some goals I can set for myself. What I hope is this:

- We will reflect critically on the compromises we make and fight against those that don’t fit our values. We can say “no, we aren’t going to spy on our students to demonstrate value, here’s why, and here’s how we’re going to document our value differently.” Take courage. Resist in small ways. Do it daily.

- We will join with others in the fight to take our information infrastructure back from corporate control. This means engagement in political battles about who gets access to the internet and on what terms, resistance to both government and corporate surveillance, and resistance to the use of proprietary black-box algorithms in making decisions about housing, health, education, and law enforcement. We should stay informed about these things and in turn inform our communities. We see information as systems, and we are trusted. Let’s become irresistibly positive public agitators, recognized for our passion about our values, values that matter to everyone.

- We will be responsible citizens in our communities, allied in struggles for fair labor conditions, environmental stewardship, and human rights. We spend so much time talking to other librarians. What if we spent half of that time reaching out and making ourselves heard? If I spent as much time talking to my local academics about open access as I did venting to librarians, maybe I’d make a dent. If I turned my concerns about privacy into local workshops, maybe I’d help my neighbors. I don’t know about you, but I don’t find this easy. It takes me out of my professional comfort zone. It isn’t what my workplace expects of me. It makes me nervous. But it’s worth it, because our values are about so much more than libraries, and they could do a lot of good if we applied them more widely.

There is hunger for this kind of change. Ursula Le Guin said at the National Book Awards a few years ago

We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art – the art of words.”

For us, it begins in our values: our care, our compassion, our belief in our own responsibility for the public good. As a profession we’ve had a century and a half to develop our guiding ethics. Google and Facebook have been in existence for less than two decades. Their stunted values are antithetical to ours. Since they and their kind are unwilling and incapable of fixing the problems they’ve created, the existence of libraries and the values they represent are a blueprint society could follow to demand change. At least, so I hope.

Sources

Dana, John Cotton. “Anticipations, or what we may expect in libraries” Public Libraries vol. 12, no. 10 Dec. 1907, p. 382

— “Anticipations, or What We May Expect in Libraries,” Public Libraries, 1907, reprinted in Libraries: Addresses and Essays, H. W. Wilson, 1916, pp 147-152.

Dewey, Melvil. “The Future of the Library Movement in the United States in the Light of Andrew Carnegie’s Recent Gift.” Journal of Social Science vol. 39, 1901, pp. 139-157.

Marwick, Alice Emily. Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age, 2013.

Schlesselman-Tarango, Gina. “The Legacy of Lady Bountiful: White Women in the Library.” Library Trends 64, no. 4 (September 13, 2016): 667–86. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2016.0015.

Garrison, Dee. Apostles of Culture : The Public Librarian and American Society, 1876-1920 /. Print Culture History in Modern America. University of Wisconsin Press, 2003.

O’Neil, Cathy. Weapons of Math Destruction How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. New York: B/D/W/Y Broadway Books, 2017.

Schneier, Bruce. Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World, 2016.

Van Slyck, Abigail Ayres. Free to All: Carnegie Libraries & American Culture, 1890-1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Wiegand, Wayne A. Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library, 2015.

Image credits

Mr. Money Bags by Alec Monopoly, photo by aisletwentytwo

NYPL by Gustavo Morales Diaz

NYPL reading room by Diliff

People’s Library (Oakland) by Steve Rhodes

Andrew Carnegie by Theodore C. Marceau

Mark Zuckerbergrberg by Elaine Chan and Priscilla Chan

Boston Public Library exterior via Wikimedia Commons

American Institution via Library of Congress

Children at the Webster Branch via NYPL Digital Collections

It Can’t Happen Here poster via Library of Congress

Nazi march in New Jersey via The Atlantic / AP

This is America via National Archives

Data Visualization by Marcin Ignac

Librarian Bomber by hafuboti

Fonts

Dana Library Hand by Margo Burns

LRT Nutshell by Lauren Thompson

Rubber Stamp by Billy Argel