Libraries and Learning

System Restore: Bringing Library Values to Today’s Information Networks

(Talk given at a conference of the Private Academic Library Network of Indiana in June 2018, which had a CSI theme that year.)

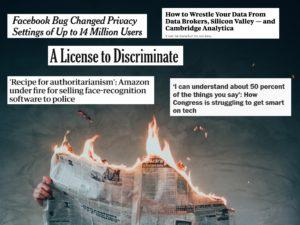

Thanks so much for inviting me to speak to you today. Full confession: I have never watched an entire episode of CSI Anywhere. I turned an episode on years ago but just couldn’t get over the fact that people who do forensic work for police investigations aren’t actually detectives and that few investigations use all that science because it’s too expensive. In fact, I’m such a feminist killjoy that it bugs me that we pretend we have scientists on hand to solve crimes when there are hundreds of thousands of untested rape kits sitting in evidence rooms across the country because DNA testing is too expensive and so many police organizations would rather spend the money on facial recognition systems and predictive policing schemes than on actual crime victims. Which is actually kind of related to what I want to talk about today.

But first, I may not watch CSI, but I read and review a lot of crime fiction. Sometimes I even write it, so you’d think I wouldn’t be such a downer. Entertainment has value and fiction is fiction, but the stories we tell ourselves for entertainment matter. Good crime fiction has the potential to give us imaginary space to think about how things go wrong and gives us practice having empathy with characters in those situations. At the same time they are popular because they also suggest things can be set right. They leave us having hope that the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice.

This morning I want to talk about how libraries can help that arc bend toward justice. Now, librarians aren’t superhuman or magical, and we make a lot of mistakes. But the values we’ve developed over the past 150 years or so matter now more than ever. Just as the CSI television franchise suggests science can solve crimes with dazzling technology that erases human error and unlocks secrets without worrying about cost, we’re living in an era of dazzling technology where we can use the computer in our pocket to organize mass movements, settle a bet in seconds, turn down the thermostat, or document a crime in progress, Tweet it, and see it later on the evening news. It all works like magic – kind of like libraries for those who use them but have no idea what labor is involved, how much it costs, or all the decisions that have to be hammered out in the background.

The CSI in PALNI means being collaborative, strategic, and innovative – all great ways to encourage one another to get stuff done and help each other out. But let’s take a step back from those three words that focus on ways to get stuff done and think about why we want to get stuff done, and why our values, library values, matter in the broader context of today’s information landscape. In particular, I want to explore what it means in our current socio-technical moment to care about these values. all of which are important in different and intersecting ways and all of which are so terribly lacking in so many of our Silicon Valley-produced information systems. Systems that seem to be failing us in some new way every day.

So, let’s look at our values: access, preservation, intellectual freedom, privacy, diversity, democracy, life-long learning, service, social responsibility, and the public good. If you are a serious student of the ALA website, you might notice I left “professionalism,” one of ALA’s core values, off this list because it seems to refer to status and educational requirements, which makes it less relevant to the wider world and also seems to defend divides in the labor that goes into making libraries work. But the argument I’m going to make this morning is that library workers, regardless of status or educational background, have collectively developed and often practiced a set of values that matter, and whatever our rank, we should advocate for them, not just in our libraries but in the world. What I want to discuss how these values, rooted in our history and in our day to day experiences or maybe just in our aspirations, matter at this moment, in June 2018.

So, let’s look at our values: access, preservation, intellectual freedom, privacy, diversity, democracy, life-long learning, service, social responsibility, and the public good. If you are a serious student of the ALA website, you might notice I left “professionalism,” one of ALA’s core values, off this list because it seems to refer to status and educational requirements, which makes it less relevant to the wider world and also seems to defend divides in the labor that goes into making libraries work. But the argument I’m going to make this morning is that library workers, regardless of status or educational background, have collectively developed and often practiced a set of values that matter, and whatever our rank, we should advocate for them, not just in our libraries but in the world. What I want to discuss how these values, rooted in our history and in our day to day experiences or maybe just in our aspirations, matter at this moment, in June 2018.

Let’s start with access. We seem to live in a world of too much information, but getting access to it may be the thing most of our community members care about when they think of our libraries. I need this article, or (if you’re a student) I need five peer-reviewed articles. Can I get this book? How do I get around this paywall? A lot of our budget and labor go into providing access to materials that are scarce and expensive by design or because of historical circumstance. At the same time, because equal access to information is something we value as a profession, we want to make that scarce information available to all, not just to our immediate community. When we promote open access publishing and run institutional repositories we’re not trying to save money, we’re trying to help research make a difference. In short, though we’re living in an age of abundance, we still have help to help people get to the things they need, and we want more people to have that access whether or not they are in our immediate community.

Abundance ≠ Access

Despite all of this effort to make information available, we too often hear from people who don’t use libraries, “why do we even need libraries anymore when you can just Google it?”

We might say “well, actually, we spend bundles of money of getting stuff for our communities,” but we also want to say “and wouldn’t it be great if everyone could get that expensive stuff?” Does that mean we think a world where everyone will “just Google it” is how we ideally will provide access someday?

Let’s think about that. What do we really mean when we insist “access to information” matters?

Every day, according to various estimates, 1.45 billion people log into Facebook to share photos and links. Half a billion Tweets are sent. A billion hours of video content are watched on YouTube. Google responds to over 3 billion search requests using the 130 trillion webpages it has indexed. In addition to all that free stuff, over 6,000 scientific articles are published daily, some freely accessible, some not, and over 6,000 books are published, not counting those that are self-published. Doesn’t that suggest libraries are small potatoes when it comes to accessing information?

Well, it’s complicated. This abundance we experience is delivered through a small handful of monopolistic platforms that don’t create or generally pay for content themselves but decide who gets to see what using proprietary systems. Though they hold their algorithms close to their chests, we’ve learned the hard way they can be gamed in ways that lead to a tidal wave of misinformation, election results warped by foreign and domestic mischief makers, and genocidal violence fanned by the flames of Facebook messages and groups. As a handful of companies corner the market on attention, they make it hard for creators of content – newspapers, for example – to have a viable business model; Google and Facebook virtually own the digital advertising market by buying competitors and developing better targeting mechanisms for the largest audiences. Besides, these systems promote engagement through emotional triggers rather than reflection. If you let YouTube decide what you might want to watch next, you’ll soon find yourself in the uncanny valley, watching extremist propaganda or extreme weirdness – or both. That’s how their curation works. They keep upping the attention stakes at the expense of more moderate or thoughtful content.

When the internet was new, search was difficult, publishing to the web was hard, and even getting online could be complicated, but for the hearty few who figured it out, it seemed freeing. Now nearly everyone is online, but they tend to go there through Google, Facebook, and a handful of additional proprietary platforms with a global reach. For a large portion of the world’s population the only internet access available is filtered through Facebook and a few select sites, except in China where Baidu, Tencent, and Chinese regulations have tempered their dominance – for now.

Besides, this abundant future is unevenly distributed: Nearly half of Americans who are low income, minority, or live in rural areas lack broadband internet service at their homes even as it becomes more vital for employment, government services, and education. The percentage of Americans who rely on phones as their connection to the internet is significantly higher among African-Americans and still higher among Latinos than among whites. If you’re poor, there’s a good chance you’ll run short on your data plans before the end of the month, and at times you’ll have to cancel service altogether because it costs too much.

Access, one of the first library values to be articulated – to freely provide information to all – may seem outdated with so much information available than ever before. But neither Google nor Facebook, despite their feel-good taglines, are guided by a well-developed code of ethics. They’re guided by a profit motive and the naïve belief that their products will magically do good so long as their shareholders do well. They move fast and break things, and now we’re seeing the unintended but all-too-predictable consequences.

As librarians we know access to information is important. We need to convey to non-librarians whose information diet is mostly coming from outside the library that access as we mean it is not the same thing as getting supposedly free stuff that has been algorithmically curated for maximum attention stickiness.

While we’re at it, let’s talk about preservation. What a can of worms. We’re experiencing not just an information explosion but practically a big bang when it comes to material culture. How many photos do you have on your phone? Stored somewhere online? How many letters that we once wrote out by hand on paper that might be preserved in an archive are now lost somewhere in a sea of emails? How often have we contributed to an online forum or posted things we created to a platform that vanished without a trace? The internet remembers too much, but it forgets all too often. I recently heard a fascinating presentation by Jack Gieseking of Trinity College in Connecticut describing a painstaking quest to recover and map the lesbian-queer history of New York City. He also described a new project – capturing a sense of trans teen cultures, which is playing out on Tumblr. This work of understanding a community and preserving its meaning requires significant reflection: unless you’re careful, every photo you takes carries an amazing amount of metadata. It’s not helpful as you try to find that one picture among thousands that have the name IMG and a number – IMG one million – but buried in the properties is a lot of information, including where you were you took a picture. Imagine how dangerous some of that could be for transgender teens. So there’s that, but my first thought was “oh, great. What will happen to this history when Tumblr folds? It was snapped up by Yahoo in a buying spree before Yahoo began to fall to bits and was bought out by Verizon, which isn’t exactly in the business of preserving culture. As more and more of our culture is placed in the hands of for-profit platforms, preserving it is a serious challenge that doesn’t figure in those companies’ business plans or their non-existent codes of ethics.

Speech: Free as in Kittens

Intellectual freedom is another core value for librarians, though it has a shorter history than access. The Library Bill of Rights was written in 1938 as a response to the rise of fascism. Nothing like burning books to get our attention – though it needs to be noted that the ALA didn’t pass a statement condemning Nazi book burnings in 1933, when it was first proposed. Librarians wanted to stay out of politics and weren’t sure censorship was a battle they wanted to own. We also shouldn’t forget that anti-fascism wasn’t universally embraced by Americans in that era. A pro-Nazi organization filled Madison Square Garden the same year that the ALA finally stood up against fascism and adopted the Library Bill of Rights. Ironically a year after that, Forrest Spaulding, the original author of the Bill of Rights, defended libraries having copies of Mein Kampf on their shelves. That kind of decision is still a stumper for us – should we give hate speech our imprimatur? – but in his words, “if more people had read Mein Kampf, some of Hitler’s despotism might have been prevented.”

As an academic librarian, I believe vile books that influenced history are important primary source documents, and it’s arguably important to be able to access and preserve contemporary documents we find offensive in order to understand perspectives that seem incomprehensible. What’s different in our current information landscape is the ways people discover and share this information. The systems they are using most often are designed to sell ads. They turn market segmentation into political polarization and push the most upsetting and extreme material to the fore within self-selected groups because it makes us click.Let’s talk a little bit about the ways that the word “free” and the concept of “free speech” have become complicated recently. The free software movement developed ways to disambiguate the meanings of the word “free.” Free as in beer (zero cost). Free as in speech (liberty). Free as in kittens (responsibility). As it turns out, the “free” tools we use most often to communicate are not free as in beer, and free speech, just like kittens, requires care and feeding.

From its birth, the internet has been celebrated as a haven for free speech but, for many, it’s a place where speaking up can unleash the wrath of a troll army with real-life consequences. Playful, anything-goes raunchiness blossomed in the shadowy channels of what had been created as an image-sharing platform for anime and manga fans. 4Chan, the site where Lolcats were born, also spun off offensive attacks on unwitting strangers picked at random as well as political movements. Anonymous adopted left-wing causes; others took a right turn and mobilized against “social justice warriors,” game developers or anyone else who dared to challenge white masculine control of internet culture. As trolls and the far right began to collaborate, the very phrase “free speech” was co-opted to unsettle college campuses with well-funded national tours of celebrity provocateurs mocking “political correctness” – and used to justify mobs marching with torches, chanting Nazi slogans in defense of Confederate monuments and white supremacy.

Libraries, which developed intellectual freedom as a core value in response to the rise of fascism and then again during the excesses of McCarthyism, when the Freedom to Read statement was adopted, have plenty of practice threading the needle of promoting freedom of speech while preserving public spaces that are hospitable to all. Remember when some company partnered with the New York City government to provide ad-supported internet kiosks on streets so everyone could have access to the internet? What could possibly go wrong? Maybe they should have talked to the librarians in the city who had already learned that some folks will park themselves for hours to watch porn and do things you don’t want to see in public yet have figured out how to negotiate what that access means in practice so all can enjoy it. Likewise, we have figured out ways to provide information that some object to without making entire parts of our populations feel unwanted or threatened. We have both values and “been there, done that” experience that could help us collaborate with others to develop tools and methods of fostering discourse that doesn’t involve silencing those we disagree with or allowing bullies to claim all the space for themselves.

Privacy Matters

Let’s talk about privacy. Some of us have had a hard time in the past persuading our colleagues that it still exists and that protecting it is really important. That we shouldn’t conduct surveillance on our students to justify our budget next year. That putting Facebook and Twitter buttons on everything is the best way to market ourselves. Seriously, why take the trouble to protect patron privacy and then sprinkle little icons through our website and catalog that send information about who’s looking at what to those corporations? How much information are we giving Google by using their analytics tools? What if people really like our defense of privacy – wouldn’t that be more likely to help our “brand” than trying to cozy up to Google and Facebook? Especially now?

Members of the US Congress were shocked, shocked to learn that Cambridge Analytica (a marketing company that bragged they had the goods on every adult American adult and could manipulate their emotions for political messaging), had exported information about tens of millions of Facebook users to use on behalf of the Trump and Brexit campaigns.

Lawmakers lined up, eager to let Mark Zukerberg have it. He, in turn, said users had total control over their privacy and blamed Cambridge Analytica for misbehaving. Yet gathering and mining personal data to influence people’s behavior has bee n Facebook’s business model from day one. (Well, not quite day one; the precursor to Facebook was a juvenile app that scraped Harvard sites to pit unwitting students in a “hot or not” face-off competition.) Data is proverbially the new oil, and Facebook, Google, and less well-known but powerful data brokers are today’s monopolistic robber barons. The internet as we know it today pumps a seemingly inexhaustible supply of personal information from all of us which can be manipulated at enormous speed, recombined with other data, and used to do everything from sell us shoes to decide whether we will get a loan, an education, or a prison sentence. And guess who else wants to get into the act? Verizon and AT&T, those friendly giants who want a piece of the adtech action and won the ability to spy on us by the same Congress that decided Mark Zuckerberg needed a good scolding.

n Facebook’s business model from day one. (Well, not quite day one; the precursor to Facebook was a juvenile app that scraped Harvard sites to pit unwitting students in a “hot or not” face-off competition.) Data is proverbially the new oil, and Facebook, Google, and less well-known but powerful data brokers are today’s monopolistic robber barons. The internet as we know it today pumps a seemingly inexhaustible supply of personal information from all of us which can be manipulated at enormous speed, recombined with other data, and used to do everything from sell us shoes to decide whether we will get a loan, an education, or a prison sentence. And guess who else wants to get into the act? Verizon and AT&T, those friendly giants who want a piece of the adtech action and won the ability to spy on us by the same Congress that decided Mark Zuckerberg needed a good scolding.

Aggregating our data for the purposes of persuasion can be used to swing presidential elections and destabilize democratic institutions. As Zeynep Tufekci has put it, “we’re building a dystopia just to make people click on ads.” With the growth of the Internet of Things, even our homes are being filled with easily-hackable surveillance devices and the streets are policed by officers who rely on private-sector products that can tell them where we go and pick our faces out in a crowd, probable cause of a crime not required.

In the US, this data-gathering is virtually unregulated and information we “voluntarily” provide to a corporation (by clicking through a long, complex, and deliberately confusing terms of service) can be obtained by the state without a warrant thanks to the third party doctrine. As Edward Snowden revealed, our government gathers massive amounts of data – so much that it has been called a “turnkey totalitarian state.” Facebook helped habituate us. The American public, still reeling from the 9/11 attacks, was outraged when the government announced a “total information awareness” program back in 2003. It was just too much power in too few hands. It was too 1984, too creepy. In response to protests, Congress immediately defunded the program. A year later, Facebook was invented and within a short time privacy seemed irrevocably lost, even though the vast majority of Americans are unhappy about it and wish they could have greater control over who has information about them.

Privacy is a core library value because, without it, you can’t feel free to explore ideas that someone else might consider dangerous. Teens need to be free to read about their sexuality in libraries without being ratted out to their parents. Scholars of radical movements need to be able to trust they won’t be turned in to the authorities for suspicious activity. Librarians have repeatedly stood up for privacy in the face of legal threats. We fight for privacy in our libraries. We should fight for it in the wider information landscape.

The Racist in the Machine

Diversity is a core library value, even though we struggle to honor it in our hiring practices. Yes, it’s problematic that we claim to value diversity but nearly 90 percent of librarians are white. Yes, there is a lot more to do to make our libraries inclusive and to ensure that we’re up front about ways our classification systems and subject headings and collections and programs fall short. But we also need to do what we can to help people understand the ways racism is reproduced in the global information systems we use every day – and in information systems that we may not even realize are operating in the background.

Let’s start with the tool so often used to find information it has become a verb. When Dylann Roof systematically murdered nine black men and women who had welcomed him into their church, he told FBI agents how he became radicalized. He Googled it.

To be sure, he started out with a predisposition to ask questions with white supremacist assumptions in mind, but algorithms enhanced his predisposition. Reporters for NPR tried to recreate his search. In spite of CSI wizardry, there is actually no way to recreate a search a particular person made in the past. But they used Google to see what kind of results they would get for the search terms he described. Not only did the top results come from white supremacist propaganda sites, auto-complete decided what they must be looking for – “black on white” must be about “crime”.

That does happen anymore. Not only does the autocomplete function suggests black on white vans, pottery, road signs, or books, the top results have nothing to do with race – or with the fact that Dylann Roof found strikingly different results. They were promoted algorithmically and, when they became a liability, they were edited out.

People make decisions that influence how algorithms work, and their often implicit assumptions push bigotry to the top of search results, show black girls pornographic images of themselves, and run ads that redline opportunity. Not only do algorithms favor sensationalism, an entire industry has sprung up to help website owners game the system because people pay the most attention to the first results. This “architecture of persuasion” designed to capture our attention not only reproduces racism, it amplifies its reach and compounds the problem. It happens over and over: A black researcher notices that when she searches for people whose names sound African American, she’s shown ads for criminal background checks. A program for automatically generating images tags labels black people as “gorillas.” The apologies and quick fixes come later.

Even more troubling are the algorithmic results we don’t even see in action generated by proprietary systems being used to choose who gets a loan, an education, a job, or a long prison sentence. These systems “learn” racism from the past and are using historical data to encode and reproduce racist practice into their decisions. And we can’t even see it happening. It’s almost always a trade secret.

Librarians have not always lived up to their values when it comes to diversity, but we can raise the question: “how can we make a case for ensuring information systems don’t perpetuate racism?” – and if that seems too tall an order, at least “how can we let people know what’s going on?”

Practicing Freedom in the People’s University

An informed populace is a prerequisite for democracy. That’s a bedrock belief that goes way back, just as fundamental a library value as access. It’s why we work in educational institutions. We are committed to helping our faculty push the boundaries of knowledge and helping our students learn, not just for the test next week but for a lifetime of curiosity and informed decision-making. We hope experiences students have in our libraries prepares them to be lifelong learners, able to participate as free human beings in a democracy.

The internet seems a powerful tool for being informed. Breaking news streams right into our hands as we glance at our phones. We can get answers to questions by simply asking them aloud in a home equipped with a digital assistant. We can find a video explaining how to fix our broken faucet on YouTube or settle a dispute in seconds with a Google search. It’s all there, just waiting for us to ask. We don’t have to rely on experts. We can do the research ourselves! But as we’ve learned in recent years, the so-called information age has become an era of disinformation, clickbait, and lies that circle the globe before the truth can get its pants on. Moreover, a public commitment to education isn’t what it used to be. Our K12 systems are no longer public in the sense of being a common experience funded by sharing the cost. Schools have to compete against one another in the name of consumer choice. Higher education has become an expensive personal investment rather than a public good, accused of being elitist even though nearly 40 percent of undergraduates attend a community college and over a third of all college students are so broke they sometimes don’t have enough to eat.

Libraries have the potential to use their values to advocate for reform across the information industries. The entwined values of democracy and life-long learning embodied in libraries – and the high level of trust in librarians as guides to good information sources – suggests tech has something to learn from us. The enormous value tech companies have created in making it possible to share knowledge and learn from one another is too important to waste on platitudes and advertising schemes.

Creating Common(s) Sense

A while back, I talked my colleagues into using a small piece of our library budget to support an open access project, Open Library of Humanities. Based in the UK, it’s a really well-thought-out platform for publishing new humanities research and flipping subscription publications to an open access model. Unlike the sciences, there isn’t much grant money going to humanities to fund publishing costs, so this model relies on member libraries kicking in a small annual amount. But we’ve grown so used to the idea that capitalism is the only way things can work, a consortium of libraries in the state of Georgia had to withdraw its support for open access projects because its legislature won’t allow tax dollars to support projects that benefit folks who don’t live in Georgia. This is not how institutions that advance learning are supposed to work.

Thanks to an influential article published by Garrett Hardin in Science in 1968, the adjective most commonly associated with the word “commons” is “tragic.” Isn’t it sad that we can’t get along, that selfishness inherent in human nature makes it impossible to share resources fairly and sustainably? Such a shame that whatever we try to do together is bound to be ruined by self-interest. This is a misconception promoted by financial interests since the 1970s to redirect public funding from providing for the common good to supporting private enterprise, which would supposedly trickle benefits down (an economic theory proven wrong decades ago). This is the underlying set of assumptions that has created an unprecedented wealth gap, shredded the safety net, and turned us against one another. It’s a philosophical stance so embedded in the technologies we use every day that the verb “share” has changed its meaning. It’s no longer about people allocating goods fairly amongst themselves, it’s a business model built on promoting attention-grabbing self-branding. You’re encouraged to constantly donate personal information, time, and relationships so your rich, interconnected data trail can be used to target advertising. And the monopolies that control that data aren’t quite sure how to fix the monster they created.

Let’s talk about solutions. The challenges we face are huge, and fixes won’t be easy. But there are some approaches that have been suggested:

- Regulate: the EU has launched a new privacy standard that could have an influence. If we had the political will to follow suit, we could reset expectations. The FTC has some clout, and the fact that Facebook has been caught out violating a 2011 consent decree suggests there are tools available to balance corporate interests with the public interest if the fines are large enough and enforcement is a priority. Tim Wu has suggested that if Congress won’t act, states could pass laws that require data-gathering companies to be information fiduciaries, required to serve the interests of their users, not just of their shareholders. Anti-trust action is another tool that needs to be applied – Facebook, Google, and Amazon have been allowed to acquire too many competitors and vertically integrate in ways that give them too much power. The last time we had extreme inequality and too much power and money in a few hands – during the first Gilded Age – we busted the trusts. We can do it again.

- Legislate: We have weak privacy laws in this country, but there’s nothing to stop us fixing that situation – though it may require first reforming campaign finance laws. Which we should do anyway.

- Create: While it will be challenging to come up with financial models and woo talent away from the likes of Google and Facebook, there are people working on new platforms that enable connecting and sharing that don’t use massive surveillance as a business model. Safiya Noble has suggested replacing Google with a public option. I think that’s a stretch, but we certainly can support developing new options and using those that are already out there.

- Protect: We need to change our national security position from offensive to defensive. This is more of a security issue than a privacy issue, but they overlap. Currently our government, like many, wants to find vulnerabilities in connected technologies – not to fix them, but to exploit them for conducting foreign surveillance. That leaves us all vulnerable. We should prioritize safety over surveillance capability. Likewise, we should insist that systems we use to automate public services and pay for with tax dollars be auditable and accountable.

- Include. There are too many places, from start-up funding to writing code, where women and people of color are shut out. It’s time to demand better conditions for women and people of color in the tech industries.

- Deliberate: Encourage and model effective public discourse from the grassroots level on up. That’s something libraries and higher ed institutions are actually pretty good at. Between sponsoring research into how platforms work, how communities online can be shaped to favor discourse over division, and holding local discussions that bridge divides, we have contributions to make.

All of those are tall orders. What can we as librarians actually do about it? It’s not like we’re sitting around bored, twiddling out thumbs. How is this supposed to fit in with all the other work we don’t have enough time to do? My suggestion is try to see the entire information landscape as we think about our roles. In particular . . .

- Learn: we’re information professionals. We have to keep up with what’s happening in the wider information landscape. If not us, who will? Is there anyone else on campus who owns this role – maybe your IT folks? Ours have to stay on top of security issues. They’re thinking about how to protect the campus. We’re thinking about how to help students be information literate and leave college ready to engage with the world. To do that, we have to be informed about the technology channels through which so much of our information flows and is shaped.

- Teach: this is a role librarians have already embraced, especially in academic libraries. We’re in classrooms, we’re talking to faculty, we’re helping students with projects. Let’s include in our educational mandate preparing students for lifelong learning and social responsibility by talking about the information systems they use and will continue to use. You’re probably asking yourselves, “Yeah, right, we’re going to fit this into a 50-minute one-shot?” Most of what our students need to learn doesn’t fit into fifty minutes. We may have to do it through other means: programming, faculty partnerships, guest lectures, documentation. What if in addition topic selection or evaluating sources or whatever is on our instruction menu we added things like dealing with misinformation or understanding online persuasion or surveillance self-defense? I think faculty would welcome us stepping up to address these issues, because it’s not in their toolkit.

- Engage: Library values have been developed over decades of thinking about information and its role in society. Maybe our users only think about what we do in terms of access, with a side of customer service thrown in. We need to get the word out that we have a comprehensive and interlocking set of values that Silicon Valley culture, moving faster than the speed of ethics, hasn’t had the time or will to develop. So many of the unanticipated outcomes we’re struggling with today could have been avoided. The fact that libraries exist – that we’re allowed to share information for the common good while respecting privacy and intellectual freedom – that’s a good sign.

There are concrete actions we can take – some immediately, some long-term – to rebuild a sense of the commons. If we reject the idea that self-interest is the primary driver of human behavior and that moneyed interests should have the power to make decisions for us, we can think creatively about retooling technology systems to support individual expression, personal growth, healthy communities, social justice, and the greater good. Another world is both possible and necessary. The fact that we still have libraries in spite of everything proves we already have an ethical scaffold for rebuilding a social infrastructure that is more just, equitable, and sustainable.

Recommended Reading

Greenfield, Adam. Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life. Verso, 2018.

Marwick, Alice Emily. Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age. Yale, 2013.

Noble, Safiya. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. NYU, 2018.

O’Neil, Cathy. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. Crown, 2016.

Phillips, Whitney. This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. MIT Press, 2016.

Tufekci, Zeynep. Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Yale, 2017.

Vaidhyanathan, Siva. Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy. Oxford, 2018.

Image credits: Burning newspaper by Elijah O’Donell on Unsplash; Computer waste recycling by Oregon State Universtiy at Flickr; What are you looking at? By Jonas Bengtsson at Flickr.