Libraries and Learning

Practicing Freedom for the Post-Truth Era

This is the text of a talk I gave on March 9, 2017 at the University of New Mexico sponsored by the Marjorie Whetstone Ashton endowment and the university library instruction team.

A PDF version can be downloaded from my library’s institutional repository or from Humanities Commons.

That shape-shifting phrase, “fake news” has been getting a lot of attention since the 2016 election and its equally puzzling precursor, the Brexit vote in Great Britain. For a short time, “fake news” was a term for those weird conspiracy theory narratives that were so compelling they led a man to “self-investigate” a pizza restaurant with a gun to rescue children who were supposedly being abused by an evil presidential candidate—a story that was simultaneously utterly implausible, entirely invisible to those who would find it implausible, and common knowledge among a large subset of conservatives who share such narratives online. That was “fake news.” So was clickbait written specifically to generate ad dollars by talented East European teenagers who understood the way the commercialized internet works. But it didn’t take long for “fake news” to become a dismissive label for entire news organizations that publish stories that do the traditional work of journalism—holding the powerful accountable.

those who would find it implausible, and common knowledge among a large subset of conservatives who share such narratives online. That was “fake news.” So was clickbait written specifically to generate ad dollars by talented East European teenagers who understood the way the commercialized internet works. But it didn’t take long for “fake news” to become a dismissive label for entire news organizations that publish stories that do the traditional work of journalism—holding the powerful accountable.

Traditionally, journalists acknowledge they are at best writing the “first draft of history” so mistakes happen, things are overlooked, and corrections have to be issued. But in spite of that, the mission is to seek the truth and report it in a  manner that is fair, independent, and publicly accountable. Critical news stories have made the current president uncomfortable to the point that he has declared press outlets that have reported news he doesn’t like not just “fake news” but the “enemy of the people.”

manner that is fair, independent, and publicly accountable. Critical news stories have made the current president uncomfortable to the point that he has declared press outlets that have reported news he doesn’t like not just “fake news” but the “enemy of the people.”

Fair warning: this is going to get political. But it’s not just my own peculiar blue-state prejudices showing. The core values of librarianship are political these days, and standing up for them requires taking a personal position. Attacking legitimate news organizations as public enemies—them’s fighting words.

They’re also historically fraught words. Enemy of the people. There’s so much to unpack here. For some of us, it evokes a vague memory of an Ibsen play in which a man pays a high price for being a whistle-blower. He wanted to let people know water was contaminated, but moneyed interests and their entanglement with government overruled a scientist’s urgent health  warning. For others who hear that phrase, it’s tantamount to hearing a death sentence being pronounced. During the terror following the French revolution Robespierre announced political crimes including spreading false news should be punished by death. It was a phrase used by Stalin so frequently during his own post-revolutionary terror that Khrushchev in 1956 renounced its use as too tainted with its result: politically-motivated mass murder.

warning. For others who hear that phrase, it’s tantamount to hearing a death sentence being pronounced. During the terror following the French revolution Robespierre announced political crimes including spreading false news should be punished by death. It was a phrase used by Stalin so frequently during his own post-revolutionary terror that Khrushchev in 1956 renounced its use as too tainted with its result: politically-motivated mass murder.

This phrase not only defines journalists as enemies, it raises the question of what we mean by “the people.” The People are those who the leader identified as genuine, patriotic, born of the homeland. The People are pure. The People are of one mind with the leader, who represents them. The enemy is anyone who outside the category of authentic People, a threat who needs to be discredited and vilified. There cannot be any disputation of the leader’s truth because it’s an attack on the People.

It’s not clear if our current president knows these historical connotations of the phrase “enemy of the people” but during the campaign he made a point of demonizing the press—encouraging mobs at his rallies to turn on the press pen, quite literally, to jeer at and physically threaten them, even as he used the spectacle to get news coverage. More importantly, he has been willing to state things that are demonstrably false without any apparent concern that fact-checking will harm his credibility. While all politicians make promises they can’t keep and deploy facts in deceptive ways in the service of persuasion, Trump shows unusual and cavalier contempt for the value of evidence in the formation of judgments. In part, he appears to draw heavily on advocacy “news” organizations ranging from the talk-show-format programs on Fox News, where the text of many of his Tweets originate, to outright conspiracy theory sites that insist on things like the moon landing was faked, Sandy Hook was a hoax, and that the 9/11 attacks were an inside job. He is reportedly a voracious consumer of news, and his news consumption choices are just that: choices. He selects those sources that suit his world view and declares the rest false by fiat.

It’s not so much that the president lies, though he does, exuberantly. He denies that the social institutions and practices that have developed since the Enlightenment to help us search for truth have any validity. He more or less has declared that truth-seeking institutions such as higher education, science, and journalism, are scams, or at best optional. The press is fake news. Global warming is a Chinese hoax. Higher education is left-wing indoctrination. And facts have no bearing because we have no agreement on what it takes to determine whether something is true.

A similar distrust led a narrow majority of Brits to vote to leave the European Union against the advice of all the experts. In fact, they voted to leave because of the experts. During the referendum, one Brexiteer made it clear the people—the true people—have had enough of experts, and so have a great many Americans. The idea of trust in expertise has become tainted as a scam perpetrated by elites against the people. And since the elites haven’t fixed or even sufficiently recognized real problems—falling incomes, rising rents, increasing job insecurity, growing inequality—there’s a lot of anger fueling general resentment about the way late capitalism has been playing out. Populist anger is being channeled by an appeal to bigotry. A man whose brand is luxury is bizarrely able to present himself as a man of the people in large part by declaring millions of Americans outside the circle of authentic personhood. Aliens. Enemies.

There are many reasons for this turn of affairs. Often people assume unenlightened beliefs are held out of ignorance and lack of education, but James Kuklinski and others (2000) have shown something more troubling: people who believe false things have plenty of information; the problem is, it’s misinformation. They cling to a rich collection of “alternative facts,” confident they are true, and they resist attempts to correct that misinformation. In fact, countering misinformation with a correction or a fact may reinforce belief in it, producing a “backfire effect” (Nyhan and Reiflier 2010). The emotional dimension of how information is presented is a further factor. People are more likely to pass on information that gives them an emotional charge than because of its information value – and information passed from one weak social tie to another is a major form of news curation today. Journalists have known about the power of emotional appeal forever, of course. That’s why stories so often begin with an anecdote about a person readers will relate to typify a problem before the larger, more abstract issue is presented. Another factor that has strongly influenced our post-truth moment: The more choices people have among information sources, the more they can select those that affirm them and avoid those that challenge their views.

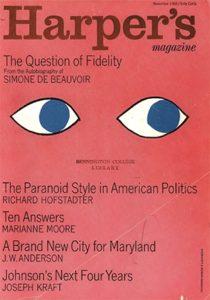

Richard Hofstadter famously described “the paranoid style in American politics” in 1964, tracing throughout our history a willingness to believe in conspiracies. These movements thrive on “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy” during times of “suspicious discontent.” Hofstadter opens his essay with the observation that “American politics has often been an arena for angry minds,” nourished by an appetite for stories that have clearly defined enemies, that cast the to-and-fro of politics as a Manichean battle between good and evil.

Richard Hofstadter famously described “the paranoid style in American politics” in 1964, tracing throughout our history a willingness to believe in conspiracies. These movements thrive on “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy” during times of “suspicious discontent.” Hofstadter opens his essay with the observation that “American politics has often been an arena for angry minds,” nourished by an appetite for stories that have clearly defined enemies, that cast the to-and-fro of politics as a Manichean battle between good and evil.

Another curious feature of these battles is not that they lack facts, but that they are so full of them. “One of the impressive things about paranoid literature,” Hofstadter writes, “is the contrast between its fantasied conclusions and the almost touching concern with factuality it invariably shows. . . . The higher paranoid scholarship is nothing if not coherent—in fact the paranoid mind is far more coherent than the real world. It is nothing if not scholarly in technique. McCarthy’s 96-page pamphlet, McCarthyism, contains no less than 313 footnote references.” This runs counter to Trump’s blithe disinterest in evidence, but it will be familiar to anyone who has been involved in a comment or Twitter war. One of the techniques that makes comments sections so tedious is the frequent demands for proof, and more proof, coupled with niggling recitations of facts that attempt to disqualify the speaker with a vast accumulation of dubious, trivial, or irrelevant facts. It becomes a war of attrition.

Hofstadter published his essay during the year Barry Goldwater ran for president on a fringe right-wing platform. But Hofstadter denied that an appetite for conspiracies had a right-wing tendency, nor are they the purview of those who were ignorant or mentally susceptible. In his view, it was a part of American mass psychology. More recent research has concluded that half of Americans of various political stripes believe in at least one conspiracy theory (Oliver and Wood 2014). The greatest appeal seems to be to those who believe some truth is hidden from them (usually by the state, though it could be the press or corporations) and that the search for truth is essentially a struggle between the good people and those who represent the forces of evil.

it was a part of American mass psychology. More recent research has concluded that half of Americans of various political stripes believe in at least one conspiracy theory (Oliver and Wood 2014). The greatest appeal seems to be to those who believe some truth is hidden from them (usually by the state, though it could be the press or corporations) and that the search for truth is essentially a struggle between the good people and those who represent the forces of evil.

As a side note, the power of narrative is a fascinating aspect of this for me. I read a lot of fiction and sometimes I write it. Getting at emotional truth matters to me, even in made-up stories. In 1999 a psychologist, Richard Gerrig, published the results of some experiments that suggest we don’t shelve fiction separately from non-fiction in our memories, and (even more interesting) we are most likely to believe ideas that come from works of fiction if we know very little about the subject matter beforehand. This is why biblical scholars were so much more likely to giggle or gag when reading The DaVinci Code than the average reader was. Some studies have shown fiction to perform a valuable service in that reading fiction appears to enhance empathy and can increase familiarity and sympathy with cultures and issues that are outside of one’s personal experience. But that power can also be used to misinform. Readers encountering something untrue in fiction may believe it and may insist that belief was encountered in a factual source before they encountered it in fiction.

Fiction can even be treated as authoritative. The first word in The DaVinci Code? “Fact.” (None of his introductory disclaimer is true, though it’s faithful to a bestseller that made claims so similar its authors unsuccessfully sued for copyright infringement.) A Michael Crichton novel, State of Fear, deliberately portrayed the science of global warming as a scientist-led conspiracy (and included a lengthy bibliography to prove his fiction was correct). A US senator chairing the Senate committee on Environment and Public Works made it “required reading” for committee members, and he called the author to provide expert testimony. One recent set of experiments has suggested that facts learned from fiction (including incorrect facts) are more likely to be recalled than facts learned from non-fiction sources (Marsh et al 2003). So we have plenty of evidence (if you believe in that sort of thing) that stories of all kinds influence us, and since many of us prefer our stories to be clear about who are the good guys and who are the bad guys, it can be all too easy for us to fall into oversimplification of complex realities.

So we live in a confusing world, where neither the CRAAP test nor extensive LibGuides will cure our susceptibility to misleading, inaccurate, fictionalized, politicized narratives that are so prominently in the news these days. What I want to focus on this morning is how we can take this moment of truth (or rather this moment of post-truth) and use it to test our thinking about how we teach our students about information and how it works. The big question for me is: What do we really want our students to take with them when they graduate? What knowledge and habits of mind matter for the long term? Where do we put our efforts while these students are with us, and does information literacy even matter at a time when the entire notion of a commonly-agreed-upon reality is in doubt? I’m going to focus particularly on undergraduate education and on how librarians and faculty in the disciplines can work together, but ultimately the question I want to pose today is “What kind of learning in college is transferable, not just to the workplace but to our lives as free human beings and citizens of a troubled world?”

Librarians have what I feel are a potent set of values, values that are salient today: providing equal access to knowledge for all, defending intellectual freedom, protecting privacy as a condition necessary for the exploration of ideas without fear, championing diversity, democracy, and social responsibility, all while promoting the value of the public good over private interests. Pretty radical stuff. Pretty valuable, given what we face today.

These values developed over time, but it’s interesting to me that the American public library originated during an era of great wealth inequality, consternation over immigration, declining incomes, the growth of a super-wealthy class, new communications technologies, the concentration of power in a few giant corporations, deskilled, underpaid, over-mechanized labor . . . it all sounds very familiar. Yet for whatever reason this was the moment when thousands of communities decided they should have public libraries, publicly-funded places where anyone could find information to better themselves. (A restricted definition of “free to all” comes into play, unfortunately; many public libraries, including those in the Jim Crow South, served only white patrons, with only a few southern cities offering “colored” branches.) About half of public libraries founded during this time were partially funded by Andrew Carnegie, a great believer in the physically-impossible bootstrap theory of personal development; a majority of libraries were founded through the work of middle class white women, who at the time were restricted in what kind of work they were allowed to do, but took a special interest in social welfare projects that fell within a broadened interpretation of their “domestic” sphere; see Schlesselman-Tarango 2016 and Van Slyck 1995. There were a lot of contradictions in the late nineteenth-century idea of a public library, but one unifying belief came to be called “the library faith.” Perhaps the first articulated value of American librarians was that free public access to information would benefit all, both for self-directed education and improvement but also as a defense of freedom and the commonwealth.

An early conflict that had to be resolved was who should decide what information was beneficial to the masses. Many librarians felt it was important to provide improving books. Fiction—particularly popular series fiction—was considered by many to be harmful and even dangerously addictive. Some librarians as a result actively practiced forms of censorship at first, refusing to stock popular titles because they might cause harm. In 1896, the director of the Allegheny, Pennsylvania public library raised this issue in his annual report, writing “It is certainly not the function of the public library to foster the mind-weakening habit of novel-reading among the very classes – the uneducated, busy or idle – whom it is the duty of the public library to lift to higher plane of thinking.” Melvil Dewey was fine with women working as librarians—they were cheaper to employ than men, for one thing—but he doubted they were capable of book selection themselves and suggested they base their choices on reviews written by qualified critics. He fought with his vice-director at the library school he founded, Mary Salome Cutler, who taught courses on literature that he considered unnecessary frills for an educational program that should emphasize efficient management, not independent judgment (Weigand 2015).

In the end, censorship lost and the people won. The public library and its librarians came to terms with the fact that self-improvement comes in many forms, perhaps best defined by the reader, and libraries ended up nourishing a democracy of tastes while continuing to claim that access to knowledge promotes democracy. In fact, librarians (particularly public and school librarians) got used to defending choices that some find objectionable. This role of defending a diversity of thought was codified first in the Library Bill of Rights, written by an Iowa library director in 1938 in response to the rise of fascism, and adopted by the American Library Association in 1939. During the McCarthy era librarians and publishers jointly authored the Freedom to Read Statement that strongly positions libraries as defenders of democracy not because they provide correct facts but because they provide a wealth of differing viewpoints. The statement claims “democratic societies are more safe, free, and creative when the free flow of public information is not restricted by governmental prerogative or self-censorship.” The statement concludes, “ideas can be dangerous; but that the suppression of ideas is fatal to a democratic society. Freedom itself is a dangerous way of life, but it is ours.”

The role of the academic library has a less fraught history than the public library. Of course libraries support education. Of course we should offer researchers a wide variety of ideas. Of course we should help students navigate all of this wealth of knowledge. Except now we are expected to ensure we have lots of metrics to prove our value because we can’t assume value, we have to prove it. It all comes down to return on investment. This metrics mind-set, coupled with an austerity regime, has contributed to what I worry is a real problem that will make it harder for us to address the challenges of a post-truth era.

When I started work at my library thirty years ago, we believed in something akin to the “library faith.” We called it bibliographic instruction. The idea was that libraries and librarians could make higher education richer and more meaningful if students were encouraged to make their own discoveries and come up with their own original problems to research. We assumed the habits and skills they gained along the way would be valuable after college. Graduates would be able to find information and evaluate it as they went on to wherever their future led. Framing questions, locating and evaluating evidence, using it to make up their minds or construct an ethical argument—surely that was preparation for life-long learning and for lifelong engagement in civil society. We took it as an article of faith, though we had little research to prove it. It was a given.

Our faith was shaken as computers came along, so we changed up our language and argument in response. In 1983 a government report scared the pants off everyone, claiming our schools were deficient to the point  that it was a matter of national security to reform them. It was the information age. Computerization threatened jobs. Japanese technical and managerial innovation threatened our global dominance. Libraries and other institutions that fed lifelong learning wouldn’t matter if education wasn’t reformed. Librarians to the rescue! In 1989 two authors, Patricia Senn Breivik and E. Gordon Gee offered a solution. It was time for a revolution in the library and it would be called information literacy. They argued that information, which was multiplying like some dangerous virus at a phenomenal rate, was a threat to the average person: “none can escape the ongoing effects of the information society on their lives, on their ability to survive if not succeed at their jobs, and on their success in living a meaningful life.” But librarians, as information experts, could guide the way provided they partnered with university leadership to revolutionize undergraduate education.

that it was a matter of national security to reform them. It was the information age. Computerization threatened jobs. Japanese technical and managerial innovation threatened our global dominance. Libraries and other institutions that fed lifelong learning wouldn’t matter if education wasn’t reformed. Librarians to the rescue! In 1989 two authors, Patricia Senn Breivik and E. Gordon Gee offered a solution. It was time for a revolution in the library and it would be called information literacy. They argued that information, which was multiplying like some dangerous virus at a phenomenal rate, was a threat to the average person: “none can escape the ongoing effects of the information society on their lives, on their ability to survive if not succeed at their jobs, and on their success in living a meaningful life.” But librarians, as information experts, could guide the way provided they partnered with university leadership to revolutionize undergraduate education.

This is our challenge to academe and to college and university presidents in particular—to take up the difficult task of reform, to find a center that holds in the fragmented world of scholarship and education. . . Be resolute in using your leadership skills to free your library personnel and resources from outmoded images and unrealistic expectations until they can become powerful allies in the work of reforming your campus. Then the goal of fully preparing young people for the challenges of the information society will become a reality ( (p. 199).

I remember reading the book at the time and feeling slightly annoyed. The implication was that faculty were falling down on the job, but higher administrators and librarians working together could shake things up. The faculty I knew tried hard to make learning meaningful. They weren’t the problem, and I didn’t know too many administrators who actually used libraries. It was always a challenge to connect with faculty in the disciplines and work together to help students become fluent and finding, judging, and creating information, but edicts from the head office would not help, at least not in my experience.

One thing that did change: faculty members who thought library sessions were unnecessary—after all, what was so hard about looking up books and scholarly articles?—were suddenly contacting me, asking for help in evaluating websites. Being diplomatic, I didn’t say students had exactly the same challenges evaluating printed information as they did websites, but that insecurity among faculty gave me a ch ance to increase our partnership. The common definition of information literacy, which actually predated the Web, became common currency. Students needed to be able to identify an information need, find and evaluate sources, and use them ethically, whether those sources were on a shelf, in a database, or on the open web.

ance to increase our partnership. The common definition of information literacy, which actually predated the Web, became common currency. Students needed to be able to identify an information need, find and evaluate sources, and use them ethically, whether those sources were on a shelf, in a database, or on the open web.

During this time, another change was underway. I found a reference to it buried in a throwaway paragraph in an article published in 2008 that replicated a study conducted twenty years previously examining mistakes made by hundreds of first year college writers from multiple institutions (Lunsford and Lunsford 2008). In the 1980s, most writing assignments in the first year were fairly short personal narratives. The focus was on learning how to express ideas clearly. In the mid-2000s, students were being assigned much longer papers that emphasized research and argument. Was this partly due to the success of librarians making claims that the library was an important site of learning? Or was it because the information age had happened and we were drowning in the stuff?

I am not sure, but I am convinced of something else: all of that research in the first year is not making our students automatically information literate. The woeful results of another major multi-institutional first year writing study, The Citation Project, suggests that students are learning how to find things. (Indeed, the findings of Project Information Literacy confirm that students aren’t relying on web searching alone, that they are nearly as likely to search library databases for sources as they are to use the web.) What they aren’t learning is why it matters. When required to write papers using sources, the first year students observed in this study tended to quote or paraphrase lines of text rather than summarize an argument. In most cases, the text they quoted or paraphrased was from the first or second page of the article—why read any further once you’ve found the bit you can use? The quotes were often taken out of context and weren’t reflective of the source’s overall argument. And the kicker? There wasn’t much original writing in these papers. They were pastiches of quoted material. This is not information literacy.

Honestly, this should come as no surprise. Writing from sources has never been a particularly effective feature of first-year writing. Back in the 1980s, when writing assignments that required sources were less common and cutting and pasting involved scissors and glue, students used similar strategies. One researcher, Jennie Nelson (1994), looking at hundreds of papers, saw very similar results. Three quarters of the students she studied used a “compile information” approach. Ten percent started with a thesis and sought out sources that would support it. Another ten percent found sources and coaxed a thesis out of them. Only five percent engaged in the recursive process of reading and questioning that writing instructors promote. Nelson described how one student she interviewed, who had been terribly anxious about a paper and procrastinated, so was writing it the night before the due date, made an outline something like this: green, brown, beige, red, green. Those were the colors of the books she planned to quote in the order in which she would quote them. And once she’d found those books and chose a topic, her stress level dropped. She explained that, since it was a research paper, she didn’t have to write anything herself, she simply had to organize and copy material. Of her 1,300 word paper, 1100 were direct quotes. This wasn’t information literacy, either.

One of the problems with trying to squeeze too much procedural knowledge into the first year writing course is that this teaching is often being performed by low-wage academics with little power to shape the curriculum beyond the first year experience and librarians who are trying to squeeze a lot of learning into a small window of opportunity. The combination of shifting the cost-burden from the state to students and the institutionalized suspicion that has insisted that we prove our value at every turn, has combined to do something rather odd: we put all kinds of emphasis on “student success” rather than on . . . what to call it? Human success? So much of our effort is geared toward making students into better students. I’m all for helping students succeed. We owe them that. I simply question whether the purpose of higher education is to turn people into college students. Or, for that matter, into biologists or sociologists or chemists, when most students graduate and do something other than what they majored in. Nor am I interested in turning students into people who have learned how to follow instructions well enough to become biddable workers. Call me radical, but that doesn’t seem to me to be the reason we do this.

So why do we care about students learning how information works? Can we even help them understand the way information works in an era of fake news, algorithmic segregation, and institutionalized suspicion? It seems to me terrifically important that librarians take seriously three separate but important functions.

We need to help students new to the university make it. We owe it to them to make the mysteries of higher education less mysterious and terrifying. We need to welcome them into the library and into the academic life. In the words of David Bartholomae, we have to help them invent the university. I’m not entirely convinced it’s a form of learning that matters, but it is a survival skill.

The second function we need to serve is to help students who have chosen a major understand the values and the discourse conventions of that major so that they can participate in disciplinary conversations and see how they work. There’s a risk that this work could become a kind of etiquette lesson rather than deep and lasting learning, but it’s in the major typically where students get the opportunity to dig deep and see knowledge being made using certain tested methods and established rhetorical moves. This is when students have enough of a knowledge base to see how the intellectual sausage is made. At this point, they have the opportunity to wrestle with unsettling concepts: knowledge is made by people like them. Everyone’s view is partial; sharing perspectives can help us see farther. Every exchange of information requires judgment. Research is recursive and non-linear. What you learn will cause you to ask new questions. You will encounter things that call into question things you believed to be true, and that can be uncomfortable. It’s okay to stick your neck out. You have a voice and something to say. Learning to ask genuine questions, gather evidence ethically, and organize a complex argument can help students understand not just how to find, evaluate, and use information, but can transform their understanding of their place in the world of knowledge.

Finally, and I feel this is more important than ever but most neglected of these tasks, we have another role: to help our communities think about why we engage students in this kind of learning and consider what is transferrable knowledge. How does the experience of presenting a poster session on a chemistry experiment at a conference or of writing a senior thesis about Victorian literature prepare students for the world they will graduate into, a world where we not only have an abundance of misinformation and distortion, but very little common ground when it comes to basic beliefs about what we know and how we know. We’ve heard a lot about how this kind of learning actually contributes toward workplace readiness. Workers need to be able to find information, weigh evidence, communicate clearly, and complete tasks. What has gotten less attention is how this kind of exploration and critical thinking prepares our students to engage with the world as citizens and perhaps change it for the better. There are signs they are up for the task—but I’m not certain we are.

One challenge is that we spend a lot of time explaining libraries and their systems without connecting them to larger information systems. Library websites are basically a slightly baffling but supposedly upscale shopping platform, offering a wealth of options for students to choose from. Working from the premise that more is always better, we work hard to expand the number of things you can find with big deals, aggregated databases that include a random selection of full text journals, and discovery layers that pull results together from many sources. If you look at your stats, you’ll probably find that a huge percentage of the full text journals available to your students never have a single article downloaded from them. When studying the use of an aggregated database at fourteen colleges several years ago (Fister, Gilbert, and Fry 2008), we found forty percent of the full text publications had zero use at all fourteen colleges in two years. Effectively, we subsidize the publication of journals nobody uses so that we can offer the illusion of lots and lots of consumer choice. Of course, those choices keep getting more expensive, so we stop buying books and cancel journals that aren’t in the package, sacrificing access to the small and the quirky, sacrificing any information that isn’t packaged into a corporate deal.

Our systems are being asked to provide the ease and attractiveness of new and ubiquitous advertising platforms. There were good lessons to learn from Amazon and Google, reminders that “save the time of the user” is just as important now as it was when Ranganathan included it among his five famous rules of librarianship. But assumptions underlying database design were too often rooted in the idea that searching for information was a consumer activity. It implied our job was to help students shop efficiently for sources to put together in a paper just as they might shop for clothing to put together an outfit.

The rise of a critical sensibility in thinking about information literacy has come at a time when late capitalism is crumbling around us. The shock of the 2008 financial crisis showed how brittle the foundations were. The unfairness of an economic and political system that claimed to be regulated through the invisible but cosmically beneficent hand of market forces has become glaringly obvious. One successful political response has been to strategically direct inchoate anger to focus on “elites” and encourage distrust of “experts” which extends to hostility toward institutions of higher learning and to entire systems of producing new knowledge, including scholarship, science and journalism. White supremacists have been able to seize the moment and focus this anger not on the captains of capitalism but on immigrants, Muslims, women, people who don’t conform to a rigid gender binary, and racial minorities.

It was only after the 2016 election in the U.S. that the algorithms that shape our view of the world—the trade-secret spying and sorting and sifting that Facebook and Google have engineered to tempt consumers to respond to advertising—have been called to account as a political force. These companies have consistently denied any responsibility for the often-dubious content they promote while designing systems to profit on its spread.

It was only after the 2016 election in the U.S. that the algorithms that shape our view of the world—the trade-secret spying and sorting and sifting that Facebook and Google have engineered to tempt consumers to respond to advertising—have been called to account as a political force. These companies have consistently denied any responsibility for the often-dubious content they promote while designing systems to profit on its spread.

This is a serious crisis of legitimacy. Institutions that failed to stem growing inequality and the effects of global capitalism have been designated elites and enemies of the people.

Librarians have, quite understandably, as when we first worried about the information age, positioned themselves as a solution to the crisis, rushing in with CRAAP tests and LibGuides and lesson plans on how to spot fake news. But this is not enough. The problem isn’t spotting falsehoods, it’s that a large percentage of our population has lost faith in the very idea that we have a shared reality and that we have developed a common set of tested methods we can use to understand it. We also have little wide-spread knowledge of how tools we use every day actually work and why in so many ways the exacerbate misinformation. We need a thoughtful, critical approach to information literacy that goes beyond thinking like a college student, thinking like a history major, thinking like a worker, but rather thinking like a free human being who has the capacity to make change.

Though it would be a mistake to promote libraries as arbiters of facts, this is a good opportunity for us to invite our faculty colleagues to discuss exactly how these things we ask students to do—keep lab notebooks, write literature reviews, compose fifty-page senior theses—prepare them for life after college. It’s not obvious. Rather than fall back on talking points about education as preparation for the workforce, it’s time to reflect in concrete ways on how these learning experiences prepare our students for a fulling life as citizens in a troubled world. (Admittedly, this won’t be a winning argument with legislators, but it’s something educators should take seriously.) And if these things we do don’t provide that preparation, we need to ask—what should we be doing?

The neoliberal economic policies and libertarian politics embraced by tech tycoons have inadvertently created a system for promoting falsehoods and undermining the sense that Americans have something in common. Google tweaks its algorithms constantly, but recently claimed it had to be neutral and couldn’t interfere when the top search result for the query “did the Holocaust happen?” was a neo-Nazi site that answered the question with hateful lies. When critics suggested the false news stories shared on Facebook influenced the 2016 election, the company denied responsibility, insisting it’s not a news organization, it’s simply a platform – a platform that has become a major news source for many of its 1.6 billion users.

Though Google’s stated mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” and Facebook claims “to give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected,” both companies are actually in the advertising business, selling the attention of their users to third parties. In order to maximize ad placements, they create cocoons of similarity where people settle comfortably into like-minded communities. When the same search query produces different results for people based on their profile and location, the idea that we’re operating in a shared reality is hard to sustain. When a social platform feeds us information designed both to sooth and stimulate us in order to keep us clicking to feed the platform’s inexhaustible hunger for personal data, it undermines the civic benefit of exposure to multiple viewpoints. When propagandists take the place of news organization, the first draft of history is rewritten as self-serving speculative fiction.

Even authoritarian states get into the act. Russia’s talented coders have not only engaged in cybercrime, they have flooded social media with disinformation and abuse flung at those who criticize their leader or express support for his designated enemies. Automated propaganda accounts on Twitter and Facebook that tirelessly send out computer-generated messages have been used in several countries to influence public opinion. One study estimated some 400,000 “bots” sent out computer-generated Tweets related to the 2016 election, each account spewing thousands of messages daily and accounting for about a fifth of election-related Twitter content. They can be coded cleverly enough to appear human as they identify and amplify messages while swarming and drowning out the voices of their masters’ opponents.

By entrusting our information infrastructure to profit-driven and unaccountable companies and their shareholders, we’ve forfeited a shared understanding that truth can be sought using methods that are designed to reduce bias to create a common understanding grounded in reality, not personal choice. The intellectual freedom that libraries value is built on Enlightenment ideals and the optimistic belief that people are curious about the world and are able to make up their own minds provided they have the liberty to explore a wide range of ideas and viewpoints. The fact that libraries are local institutions rather than global profit-driven enterprises grounds that faith in a commitment to provide all Americans equal access to the same foundation of knowledge.

So what can we do in a practical sense?

Psychologists have offered some suggestions about how understanding the cognitive factors that make people resistant to having their misinformation corrected (Lewandowsky et al. 2012). Some of this is common sense. Don’t repeat misinformation repeatedly as you try to debunk it, but instead emphasize the facts you wish to convey. Consider what gaps in people’s mental event models are created by debunking and fill them using an alternative explanation. Consider how your audience might feel threatened by an explanation, and seek a way to make it affirming in some way. Tell stories that are emotionally compelling for your audience that improve their understanding, or expose people to stories that boost empathy. And of course use the On the Media “breaking news consumer handbooks” liberally.

As librarians, we have more tools at hand than LibGuides and one-shots. We have literal places—large buildings—where we can promote our values: democracy, diversity, intellectual freedom, privacy, the value of lifelong self-directed learning. We can plant reminders everywhere, in book displays, on white boards, on our websites, in programs. We have a lot of social capital we could be spending. Libraries have higher credibility across political divides than almost any social institution. Let’s use that good will to bring people together. Help our campus communities understand the ethical decisions that go into making good research and why these ethical choices matter. Help them understand how Facebook works, how ad networks work, how Big Data is being used to sort us into malleable categories and what’s wrong with that picture. Reject neutrality. Become activists for our values, and do what you can to help our faculty think about their role in preparing their students for a troubled world. Simple solutions won’t solve this crisis, but I’m convinced the values librarians have developed over the years are exactly what this moment needs. Let’s go forth and practice them.

References

Bartholomae, David. “Inventing the University.” Journal of Basic Writing. 5, no. 1 (1986): 4-23.

Ecker, Ullrich K. H., Stephan Lewandowsky, and David T. W. Tang. “Explicit Warnings Reduce but Do Not Eliminate the Continued Influence of Misinformation.” Memory & Cognition 38, no. 8 (December 2010): 1087–1100. doi:10.3758/MC.38.8.1087.

Fister, Barbara, Julie Gilbert, and Amy Fry. “Aggregated interdisciplinary databases and the needs of undergraduate researchers.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 8, no. 3 (2008): 273-292.

Gerrig, Richard J. Experiencing Narrative Worlds: On the Psychological Activities of Reading. New Haven [u.a.: Westview Press, 1999.

Kuklinski, James H., Paul D. Quirk, Jennifer Jerit, David Schwieder, and Robert F. Rich. “Misinformation and the Currency of Democratic Citizenship.” Journal of Politics 62, no. 3 (August 2000): 790.

Lewandowsky, Stephan, Ullrich K. H. Ecker, Colleen M. Seifert, Norbert Schwarz, and John Cook. “Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 13, no. 3 (December 1, 2012): 106–31. doi:10.1177/1529100612451018.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and Karen J. Lunsford. “‘Mistakes Are a Fact of Life’: A National Comparative Study.” College Composition and Communication 59, no. 4 (June 1, 2008): 781–806.

Marsh, Elizabeth J, Michelle L Meade, and Henry L Roediger III. “Learning Facts from Fiction.” Journal of Memory and Language 49, no. 4 (November 2003): 519–36. doi:10.1016/S0749-596X(03)00092-5.

Nelson, Jennie. “The Research Paper: A ‘Rhetoric of Doing’ or a ‘Rhetoric of the Finished Word’?” Composition Studies/Freshman English News 22, no. 2 (1994): 65–75.

Nyhan, Brendan, and Jason Reifler. “When Corrections Fail: The Persistence of Political Misperceptions.” Political Behavior 32, no. 2 (June 1, 2010): 303–30. doi:10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2.

Oliver, J. Eric, and Thomas J. Wood. “Conspiracy Theories and the Paranoid Style(s) of Mass Opinion.” American Journal of Political Science 58, no. 4 (October 1, 2014): 952–66. doi:10.1111/ajps.12084.

Schlesselman-Tarango, Gina. “The Legacy of Lady Bountiful: White Women in the Library.” Library Trends vol. 64 no. 4 2016, pp. 667-686.

Van Slyck, Abigail Ayres. Free to All: Carnegie Libraries & American Culture, 1890-1920. University of Chicago, 1995.

Wiegand, Wayne A. Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library, Oxford, 2015.

Image credits

Newspapers – Neil Turner

New York Times – Sam Chills

Ta Dah – Mario Klingemann

This is Fine – k c green

Original Google – pingdom

Balloon Girl – wiredforlego