Libraries and Learning

Doing Our Copyright Homework

September 20, 2015

When I started library school many years ago, I didn’t realize I would be thinking about copyright on a regular basis. Oh, we posted a copyright notice over every photocopier warning library users to avoid violating the law, but questions about whether something was legal or not came up relatively infrequently in the first decade of my professional life. The internet changed all that because it changed the way we share scholarship. Now, copyright law intersects with our everyday practice as librarians, teachers, and scholars, and keeping up with legal interpretations is part of our work.

Of course, not everyone wants to bother with legal ambiguities. People avoid copyright issues by being over-cautious, letting corporations and their proxies tell us what we’re allowed to do or by adopting convenient work-arounds that aren’t always legal but feel natural in a connected world. But ignoring the role copyright plays in our lives and its constant evolution is problematic because we’re implicated.

Here’s an example of a court case that will likely become part of how I think about copyright. Last week, the Ninth Circuit court handed down a decision in a case that first made news in 2007. A woman made a video of her baby, happily bouncing to a tune on the radio playing faintly in the background. She put it on YouTube so that she could send the link to friends and family. A lot of people found it irresistibly cute, though I very much doubt any of them thought it was a substitute for buying a recording of Prince’s “Let’s Go Crazy.” Universal issued a take-down notice to YouTube, saying it violated Prince’s copyright (and the corporation’s financial interest in that copyright). The mother, with the help of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, argued that it was clearly a fair use. Eight years and multiple motions later, the court has ruled in her favor.

There are two significant things about this opinion that pertain to the kinds of fair-use decisions academics have to make constantly. First, as Kevin Smith emphasizes, fair use is not simply an affirmative defense, it is a right. The court says so definitively. Second, owners of intellectual property must consider whether a use is fair before issuing a take-down notice. This is a fair use win.

However, as Sarah Jeong notes, the decision isn’t a slam-dunk victory. The court has ruled that rights holders and their proxies are responsible for wrongfully issuing a take-down notice – but they can be held responsible only if they knew they were in error. In 2007, a human being made that judgment call. Now these alleged copyright violations are sought out by robots, not humans applying a complex set of factors to a particular instance. It would be quite difficult for a litigant to prove a robot’s malicious intent, and there aren’t many people willing to spend years trying to assert their legal rights against the workings of algorithmic judgment.

All that said, this is one of a long series of court cases that firm up the notion that fair use is a right, and even though it can be difficult to exercise it in an era where algorithms make the decisions, it’s one that we should exercise in order to preserve the public good. Too often, copyright is seen as a simple property right, when in fact it’s a limited monopoly granted by the government in order to balance creators’ incentives with the advancement of knowledge and creativity. Big money interests have managed to tilt the statutes toward rights holders and against the public interest, but lately case law has remind us that the public has rights, too.

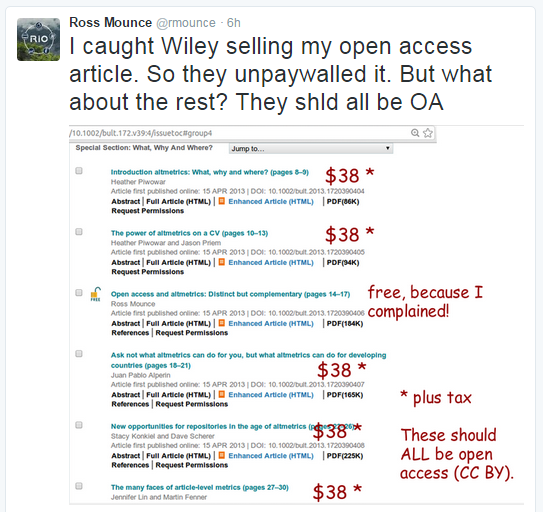

I’m thinking about this while also mulling over the fact that, once again, one of the five giant commercial publishers who own the copyright to half or more of our current published scholarship has been caught selling open access articles fraudulently. Did the publisher act illegally? No – the articles were published under a generous Creative Commons license, the authors deliberately inviting reuse because reuse is helpful for advancing knowledge. But for a major scholarly publisher to take articles that the authors made open access and sell them to unsuspecting researchers and the librarians who serve them is underhanded and scuzzy. And it’s happened before.

I doubt that putting a price tag on these open access articles was deliberate. Like the robot-driven take-down notices, Wiley and other giant publishers have made ingesting articles into its massive database so routine that it can’t handle the subtleties of copyright or accommodate oddities like authors (with the blessing of their scholarly society) asserting rights authors normally give away with little thought. The system is built that way. Asserting your rights takes work. It goes against the system.

The more we accept routines that lock up intellectual property without question, the fewer rights we’ll have. This is why we all need to keep up with copyright. Our ability to share knowledge for teaching and research and for the greater good depends on it.