2 Chapter 2 – Theoretical Understandings

Looking Toward Theoretical Approaches to Intercultural Communication

“Who am I, who are you, and what are we doing here together?”

–attributed to Dr. Charles Tucker, a former professor at Northern IL University

The Tuckerian Turn

We use Tucker’s straightforward approach to learning intercultural communication skills as a way to give valuable insight into the various skills and concepts demonstrating the relationship between communication, culture, perception, verbal and nonverbal communication, listening, and intercultural communication/interviewing. As Professor Tucker states: “Communication courses ask you to consider three fundamental questions: “Who am I;?” “Who are you?;” and “What are we doing together;?” In a sense, these three questions guide the approach in this PressBook.

Professor Tucker asks his students, “Who am I?” The first question examines one’s self. It works toward knowledge of the student’s “self” by understanding who the student is as a person and, necessarily, knowing one’s own culture. Elements or components of their culture help define who the student is, i.e., whom the student regards themself to be and how, through what kind of lens, the student perceives the world (we will examine the creation of self and the process of self-identity formation in Chapter 3 in more detail). To move on toward intercultural communication competence, necessary for navigating our globalized world, individuals must honestly confront and answer but then move beyond the first question and be open to taking the risk of asking those of other cultures the second question, “Who are you?”

The first question, “Who am I?” is a key to opening the door that allows relationship and knowledge between the cultural “self” and the “other” of another culture. As explained above, this open and reciprocal relationship and expertise stem from asking the second question, “Who are you?” Intercultural communication emerges through this question posed to someone (the “other”) who is part of another, often very different culture. Remember, when asking questions of someone of another culture, one’s own culture is vital in shaping one’s identity, values, worldview, beliefs, biases, language, religion, and the means and methods of interpersonal communication.

Intercultural communication depends first upon knowledge of oneself, one’s culture, and the interrelationship between the two. This interrelationship is the foundation for meaningful intercultural communication from the “self” with the “other.” Interrelationship, then, involves knowledge of the other’s culture, i.e., a knowledge of the same cultural concepts mentioned above, used to understand one’s own culture, can now be focused on the culture of the other. Such knowledge allows for better, more informed questioning and dialogue by enabling the student to ask relevant and valuable questions to learn about the “other” and their culture.

Chapter Two Overview

The goal of the first third of the semester is to address the question, “Who am I?” This chapter reviews the fundamental concepts of intercultural communication. We will first explore the importance of our approach to thinking about cultures, using the position of relativism and universalism above. In the second part, we will integrate materials on the influences of “deep culture” — our cultural communication learned from society, family, and religion. The chapter will end, as did chapter one, with a preview of Week Two Class Discussion topics.

As noted in Chapter One and subsequent chapters, we have leaned on, and integrated, the work of other OER (open education resources) that are free to use. This OER includes videos and “additional materials” in textboxes highlighting the author’s and speaker’s ideas.

Finally, this book is a growing and evolving project: notice adjustments before the assigned reading dates. Feel free to give us feedback and ideas on chapter inclusions.

Section One: Learning Outcomes

- Understand how the three questions, “Who am I, who are you, what are we doing here together,” centers the approach to Intercultural Communication in this text

- Review the fundamental concepts of intercultural communication

- Explore the importance of our approach to thinking about cultures, using the position of relativism and universalism

- Identify the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis’s primary claims

- Define “echo chamber,” “worldview,” and “ethnocentric”

Section One: Approaches to Cultural Understanding

A note of caution, however. As mentioned, to be an effective cultural communicator/interviewer, the student must be keenly aware of the influence of held cultural predispositions and assumptions. Stephen Fuchs (2001) points out, “cultural observers are also cultured observers {coming} with a ‘habitus.’ [This] means that observers are [conditioned by their own culture and] are trained and accustomed to using distinctions of their own culture…[providing} observers with the material and symbolic means of observation….” (p.155).

Moreover, Fuchs (2001) argues for the pervasiveness of culture in shaping vital aspects of its members’ identity. The profound and pervasive influence of one’s culture shapes perception andworldview. It imparts to its members their peculiar categories, distinctions, and means of approaching and learning about the world and other cultures. Worldview refers to “how people interpret reality and events, including their images of themselves and how they relate to the world around them” (Samavor et al., 2017, p. 57). Given this, defining the terms such as beliefs and values is helpful. First, Samavor et al. (2017) share, “A belief is a concept or idea that an individual or group holds to be true. Beliefs represent our subjective conviction in the truth of something — with or without proof” (Samovar et al. 2017, p. 202). We learn beliefs. During COVID-19, one could hear different beliefs from many late-night or cable news programs about vaccination safety, efficacy, and purpose pew Research (2021) reported how Americans’ beliefs about vaccines reflect our value of individualism Values are “broad preferences concerning the appropriate course of action or outcome. [Values reflect] our sense of what ‘ought’ to be” (Worthy, Lavigne, & Romero, 2020).

Tucker’s second question, “Who are You?” emerges from knowledge of one’s culture — “Who am I?” This question points to learning about those of different cultures — “Who are You?” Notice, however, that cultural differences do not prevent acquiring a genuine, meaningful, and, in a real sense, objective understanding of different cultures through careful, informed, and respectful intercultural communication/interviewing. Intercultural communication competence occurs because, though distinct cultures shape such communication between individuals, the profound similarity of common humanity or human nature overcomes the barriers of cultural differences.

A shared human nature allows the interviewer and interviewee to open closed doors and acquire a more profound, authentic understanding of both cultures, no matter their differing or contested cultural values and norms. This notion is a reservation against cultural and linguistic relativism. Linguistic relativism arises from the “Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.” Hussein (2012) explains that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis asserts the profound influence of language on thought and perception, which strongly implies that speakers of different languages from different cultures perceive reality differently–language, in effect, determines worldview (p.642).

As opposed to relativistic views of culture, the universalist perspective stresses that language and culture do not bind individuals only to their particular cultural concepts and constructs, blinding them to a legitimate understanding and evaluation of other cultures. Knowledge, honesty, respect, and openly observing, learning, evaluating, and interacting lead to understanding different cultures. This helpful understanding may, unfortunately, be contested or clouded by the concept discussed in Chapter One briefly, of cultural relativism.” It asserts that individuals consciously or unconsciously hold to some form of cultural or linguistic differences regarding cultural, religious, social, political, legal, familial, economic beliefs, norms, and traditions of a given culture to be equal and above criticism by those of other cultures (Chin-Dahler, 2010). Cultural relativism holds that all aspects of culture are products of cultural context relative to different cultures and contexts; cultural norms, values, and practices are equally valid. Thus, any given culture’s evaluation, assessment, or judgment must be internal only; cultural criticism must come only from persons of that culture. Persons of other cultures and traditions with different perceptions, values, and worldviews cannot reach the point where moral judgment or evaluation regarding another culture is valid. A universalist position and its evaluation of the “other” (other cultures) is not based upon simple cultural biases such as ethnocentrism/pb_glossary]" - a concept where one's cultural worldview, beliefs, and practices as superior to those of other cultures.

Cultural relativism, though, opposes all elements of universalism. However, universalism is not necessarily ethnocentric. Moreover, reasonable universalism should not be considered an obstacle to intercultural understanding, respect, and dignity. Universalism opposes [pb_glossary id= "1712"]cultural relativism, which, again, holds that a culture's values emerge within the context of particular social, cultural, economic, political, geographical, and environmental conditions. Hence, each culture is relative and equal to others and only assessed according to a member's cultural lens, boundaries, and worldview.

The universalist view should be culturally sensitive and amenable to communicating with, and learning about, other cultures. One must adopt an attitude of openness and neutrality and closely monitor or even censor one's judgments of different cultures. Remember, for cultural relativism, individual values and worldviews are culturally determined. All cultures and aspects of cultures are equal. Interestingly, cultural relativism holds a universalist belief and moral standard - tolerance of all cultural values. Yet individuals of one culture (e.g., a western culture) lack a legitimate basis for criticizing the cultural practices of other cultures. Therefore, cultures that are patriarchal (men hold all power), practice female genital mutilation, polygamy, or arranged marriages of underage girls' cannot be morally evaluated. Moreover, cultures practicing such values often defend them as legitimate because they are traditional cultural practices they wish to preserve. Cultural relativism, which asserts that all cultures can not be evaluated and holds to its primary value of tolerance, lacks any basis (e.g., the declaration of Human Rights) to criticize cultural practices such as those mentioned above.

For cultural relativism, cultures must be tolerant and non-judgmental in the face of cultural practices and beliefs other than one's own. Such a stance is unfortunate. In the history of the United States, for example, many foreign and domestic critics appealed to standards of inalienable and universal human equality and justice as articulated in the Declaration of Independence or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to point out the glaring hypocrisies of the dominant American culture (e.g., slavery, the genocide of Native American cultures, Jim Crow, denial of voting rights) to live up to guiding principles. Yet those who adhere to cultural relativism are reluctant to appeal to consistent universal transcultural principles of inalienable human rights or justice, which hold certain cultural practices as disgusting, vile, and unjust.

Professor Patrick Deenan (2012), referring to American culture, was struck by one of Allan Bloom's evaluations of relativism in American culture:

Bloom made an...argument [accounting for] cultural relativism: American youth were increasingly raised to believe that nothing was True, that every belief was merely the expression of opinion or preference. Americans were raised to be 'cultural relativists,' with a default attitude of non-judgmentalism [or "tolerance]. Not only all other traditions but even one’s own (whatever that might be) were simply views that happened to be held by some people and could not be judged as inferior or superior to any other. [No opinion held by one person can be determined to be superior to the opinion of another; nor can any one culture be assessed by the values of another or universal values, for that matter]...(Deneen, 2012).

Finally, suppose beliefs, values, attitudes, language, and worldview were, in fact, fundamentally culture-bound. In that case, researchers/business people/individuals from one culture could not understand and communicate deeply and meaningfully with those of another. Ironically, the concepts of culture and relativism are mostly "constructs" or insights of various thinkers of Western cultures. These concepts, d, do not diminish their explanatory effectiveness or usefulness for cultural communication competency and understanding between individuals of different cultures (Nisbett, 2003).

The Tuckerian Turn: Beware the "Echo Chamberbeliefs:"

Interviewees who attempt to forthrightly respond to the "Who are you?" question(s) impart valuable insights into their particular perspective of their own culture. These insights emerge from Professor Tucker's third question, "What are we doing here together?" As we shall see, this question eventually leads to intercultural communication competence and confidence.

Regarding Professor Tucker's third question, "What are we doing here together?" along with its intercultural perspective exists, unfortunately, in divisive times where a barrier or wall, largely self-imposed, impedes or prohibits moving from the notion of "Who am I?" (i.e., understanding our own culture) to an honest consideration of the next question, "Who are you?" A question asked of someone from a different culture is fundamental to begin learning about other cultures and thus engaging competently in intercultural communication through Tucker's third question. A wall between cultures emerges; it prevents moving forward from Professor Tucker's first question by limiting, in our social media age, our communication to those people who are "just like me" in many aspects of culture: nation, appearance, political opinions, economic circumstances, religious beliefs, social practices and overall values, norms, and worldview. A straightjacket is applied and tied to our views and conversations, limiting our conversation to unchallenging "like-minded friends," and comfortable "contacts"--often termed the echo chamber--in which the dialogue consists of "Who am I?" and perhaps "Who are we?" and, finally, "Why are they out to get us--we who are guardians of the true and good?"

In his professional blog, Communication scholar John Stewart (2017) remarks,

It's called the ‘echo chamber syndrome….’ We only listen or speak inside closed chambers that echo [and amplify] our current beliefs and opinions.”

The result, Stewart continues, is polarized (or polarizing) communication of one-sided arguments preached to the choir that necessarily "reduce[s] the quality of our critical thinking" (2017). Moreover, says Stewart, such communication divides us from friends, family, and colleagues--indeed a danger to democracy, the health of which requires open, honest civil discourse. In sum, we become trapped in a "Thunderdome" of our own making, where any deviation from the loudest "Echo" is promptly ostracized. Read more: example. To gain more information about critical thinking and acquire a better vocabulary of terms related to critical inquiry, see this link.

Note that cultural relativism is entirely consistent with this development. All cultures are equal in all respects. If no means exists to assess and evaluate cultural principles and practices, then responses, for example, to questions like, "Why was racial apartheid in South Africa wrong?" are reduced to relativism or a vague answer to apartheid "being on the wrong side of history."

Activity Application - Consider the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Source: (United Nations, 2022).

Consider the BBC News Report about the Uighur "Detention Camps"

A student in a public speaking class shared her alarm and concern about learning that Muslims in China were being persecuted and so few of her peers were aware of this topic. She added information to her speech from the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) you'll find embedded below in the video. In her speech, she shared the report of what had been happening. Next, she shared her belief that this report was true. Her values led her to assert that the detention camps were wrong. Further, the behavior, she argued, violates the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Her assertion illustrates how one might not be a part of a culture but still call for action based on Human Rights. Read the United Nation's Universal Declaration of Human Rights below. How would you respond to the student's speech if you were in her audience? Would your response align with the relativist (not my culture, not my judgment) or a more universalist (not my culture, but internment camps and persecution are wrong no matter where you live) viewpoint? Is there a middle ground? These questions may seem hypothetical, but we hear stories in our towns and places far beyond our neighborhoods with globalization. The question of who am I, who are you, and what are we doing together can also be asked in these international settings.

What is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights?

"The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a milestone document in the history of human rights. Drafted by representatives with different legal and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world, the Declaration was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 (General Assembly resolution 217 A) as a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations. It sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected and it has been translated into over 500 languages. The UDHR is widely recognized as having inspired, and paved the way for, the adoption of more than seventy human rights treaties, applied today on a permanent basis at global and regional levels (all containing references to it in their preambles)" (United Nations, 2022).

See videos from the United Nation on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights here.

Illustrated Version of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Yacine Ait Kaci's beautiful illustrations of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, originally published on the United Nations website are copied/reproduced below with permission (with attributions at the end of this textbox). As you consider the declarations, think about the tension we find in wanting to accept others' cultural practices and beliefs with the balance of wanting to enforce what are called, "Human RIghts." This is, the challenge studying intercultural communication asks you to take.

Preamble

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,

Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law,

Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations,

Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in cooperation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms,

Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge.

*See Appendix B for the full Declaration of Human Rights.

Section Two: Looking at Different Methods of Studying Intercultural Communication

Section Two Learning Outcomes

- Develop an understanding of the influences of "deep culture" on intercultural communication

- Identify the "Cultural Iceberg Model's" key components

- Understand "Hofstede's Dimensions of Culture"

- Identify low and high-context cultures

- Apply the notions of this chapter to current events and topics in everyday life

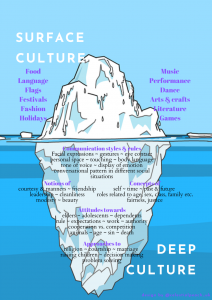

Deep Culture

Samavor, et al. (2017) explain that "deep culture" comprises social, family, and religious influences. Sometimes the "Cultural Iceberg" is used to help visualize all the impacts on intercultural communication they explain:

The key to how members of a culture view the world can be found in that culture’s deep structure. It is thisdeepstructure,theconsciousand unconsciousassumptionsabouthowthe world works, that unifies a culture, makes eachcultureunique,andexplainsthe “how”and“why”of a culture’s collectiveaction—an action that is often difficult for “outsiders”to understand. The aspects of deep structure are sources of insight because they not only deal with significant universal questions, but examining ethics, notions about God, nature, aesthetics, and even death leads to helping people understand“the meaning of life.” At the core of any culture’s deep structure are...social organizations....These organizations, sometimes referred to associal institutions,are the groups that members of a culture turn to for lessons about how to live their lives. Thousands of years ago, as cultures became more and more advanced and their populationsgrew, they began to realize that there was a need to organize in a collective manner. These collective institutions, which offer their members“rule-governed relationships,” serve the purpose of holding“members of a society together.”1Bates and Plog repeat this important notion about social organizations when they note,“Our ability to work in cooperation with others in large social groupings and coordinate the activities of many people to achieve particular purposes is a vital part of human adaptation.”There are a number of groups within every culture that help with that adaptation process while also giving members of that particular culture guidance on how to behave. he three most enduring and influential social organizations that deal with deep structure issues are (1) family (clans), (2) state (community), and (3) religion (worldview). These three social organizations—working in concert—define, create, transmit, maintain, and reinforce the basic and most crucial elements of every culture (Samavor, et al, 2013, p. 60).

Edward T. Hall's Cultural Iceberg Model

from the folks at www.constantforeigner.com © 2010

Iceberg Model

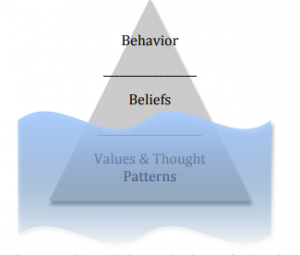

In 1976, Hall developed the iceberg analogy of culture. If the culture of society was the iceberg, Hall reasoned, then there are some aspects visible above the water, but there is a more significant portion hidden beneath the surface.

What does that mean?

The external, or conscious, part of culture is what we can see and is the tip of the iceberg and includes behaviors and some beliefs. The internal, or subconscious, part of culture is below the surface of society and consists of some beliefs and the values and thought patterns that underlie behavior. There are significant differences between the conscious and unconscious aspects of culture.

Internal vs. External

Implicitly Learned Explicitly Learned

Unconscious vs. Conscious

Difficult to Change vs. Easily Changed

Subjective Knowledge vs. Objective Knowledge

What can we do?

Hall suggests that the only way to learn the internal culture of others is to actively participate in their culture. Only the most overt behaviors appear when one enters a new culture. As one spends more time in that new culture, the underlying beliefs, values, and thought patterns that dictate behavior will be uncovered. This model teaches us that we cannot judge a new culture based only on what we see when we first enter it. We must take the time to get to know individuals from that culture and interact with them. Only by doing so can we uncover the values and beliefs that underlie the behavior of that society.

More on the Iceberg Model

Other Images of the Cultural Iceberg

https://www.celestialpeach.com/blog/cultural-iceberg-cultural-appreciation

In the "Celestial Peach Blog," the author shares:

"In its original context, the iceberg model was intended to address the stress of adjusting to new cultures i.e., culture shock. But in 2020, I believe this model is still relevant as a tool for cultural appreciation.

In the U.S., we believe we live in a fairly open and diverse country. But, speaking from personal observation and experience, it often seems that we still lack a deeper level of appreciation for the many different cultures that make up our society. For example: Chinese people have centuries of integrated history and contribution to the U.S., yet it feels like takeaways and festivals still define us. I am disappointed at how little I am asked about my Chineseness beyond where to eat Chinese food. Sure, I use Celestial Peach as a platform to talk about Chinese food, but always with a view to how it's linked to my heritage and identity.

In recent years, there have been inflammatory debates in the food industry about who gets to cook whose food. It's not about the food itself, it's about acknowledging that food is a magnifying glass onto hidden layers of culture. The cultural iceberg is a useful tool for anyone who wishes to engage more with another culture, whether on a professional or personal level."

Take some time to add "cultural iceberg into Google." The metaphor has expanded. Here are some of our finds:

https://blog.empuls.io/iceberg-model-of-culture/

Diving deeper into "Deep Culture," one might better understand how social structure influences one's sense of self by applying Hofstede's Dimensions of Culture.

Social Structure's Influence and Hofstede's Dimensions of Culture

Looking toward society and social influences on our sense of self and intercultural communication brings us to look at Hofstede's Dimensions of Culture.

Green, Fairchild, Knudsen & Lease-Gubrud (2022) share the following information in their OER Textbook.

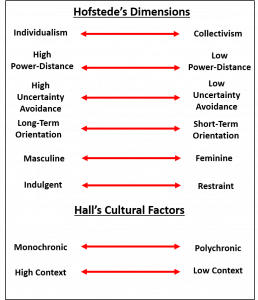

Hofstede's Dimensions of Culture

Learning Outcomes:

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- apply Hofstede's dimensions of culture to oneself and a group.

- show how Hall's cultural variations apply to oneself and a group.

Hofstede's Dimensions of Culture

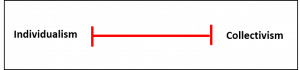

Individualism and Collectivism

According to Hofstede,

The left side of this dimension, called Individualism, can be defined as a preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of themselves and their immediate families only. Its opposite, Collectivism, represents a preference for a tightly-knit framework in society in which individuals can expect their relatives or members of a particular in-group to look after them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty. A society's position on this dimension is reflected in whether people’s self-image is defined in terms of “I” or “we” (Hofstede, 2012a).

In a highly individualistic culture, members can make choices based on personal preference with little regard for others, except for close family or significant relationships. They can pursue their wants and needs without concerns about meeting social expectations. The United States is a highly individualistic culture. While we value the role of certain aspects of collectivism, such as government, social organizations, or other forms of collective action, at our core, we firmly believe it is up to each person to find and follow their path in life.

In a highly collectivistic culture, just the opposite is true. It is the role of individuals to fulfill their place in the overall social order. Personal wants and needs are secondary to the needs of society at large. There is immense pressure to adhere to social norms and those who fail to conform risk social isolation, disconnection from family, and perhaps some form of banishment. China is typically considered a highly collectivistic culture. In China, multigenerational homes are common, and tradition calls for the oldest son to care for his parents as they age.

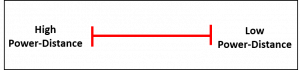

High Power-Distance and Low Power-Distance

The power distance dimension of culture expresses the degree to which the less powerful members of a society accept and expect power to be distributed unequally. The fundamental issue is how a society handles inequalities among people. People in societies exhibiting a large degree of power distance accept a hierarchical order in which everybody has a place and which needs no further justification. In societies with low power distance, people strive to equalize the distribution of power and demand justification for inequalities of power (Hofstede, 2012a).

In high power-distance cultures, the members accept some have more power, and some have less power and that this power distribution is natural and normal. Those with power are assumed to deserve it; likewise, those without power are believed to be in their proper place. In such a culture, there will be a rigid adherence to the use of titles, "Sir," "Ma'am," "Officer," "Reverend," and so on. The directives of those with higher power are obeyed with little question.

In low power-distance cultures, power distribution is considered far more arbitrary and viewed as a result of luck, money, heritage, or other external variables. For a person seen to have power, something must justify their power. For example, western cultures view a wealthy person as more powerful. Elected officials, like United States Senators, will be seen as powerful since they had to win their office by receiving majority support. In these cultures, individuals who attempt to assert power are often faced with those who stand up to them, question them, ignore them, or otherwise refuse to acknowledge their authority. When titles fall out of use, they figure far less in high power-distance culture. For example, in colleges and universities in the U.S., it is far more common for students to address their instructors on a first-name basis and engage in casual conversation on personal topics. In contrast, in a high power-distance culture like Japan, the students rise, bow as the teacher enters the room, address them formally at all times, and rarely engage in any personal conversation.

High Uncertainty Avoidance and Low Uncertainty Avoidance

As you have already learned in this course, humans do not like uncertainty, and the drive for certainty, predictability, and comfort is quite strong. How cultures handle uncertainty varies:

As you have already learned in this course, humans do not like uncertainty, and the drive for certainty, predictability, and comfort is quite strong. How cultures handle uncertainty varies:

The uncertainty avoidance dimension expresses the degree to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. The fundamental issue here is how a society deals with the fact the future can never be known: should we try to control the future or just let it happen? Countries exhibiting strong [uncertainty avoidance] maintain rigid codes of belief and behavior and are intolerant of unorthodox behavior and ideas. Weak [uncertainty avoidance] societies maintain a more relaxed attitude in which practice counts more than principles (Hofstede, 2012a).

Consider how one avoids uncertainty: by limiting change, adhering to tradition, and sticking to past practice. High uncertainty avoidance cultures place a very high value on history, doing things as done in the past, and honoring stable cultural norms. Even though the U.S. is generally low in uncertainty avoidance, we can see evidence of higher uncertainty avoidance related to specific social issues. As society changes, many will decry the changes as they are "forgetting the past," "dishonoring our forebears," or "abandoning sacred traditions." In the controversy over same-sex marriage, the phrase "traditional marriage" refers to a two-person, heterosexual marriage, suggesting same-sex marriage violates tradition. Changing social norms creates uncertainty, and for many, changes are very unsettling.

In a low uncertainty avoidance culture, change is seen as inevitable, normal, and even preferable to stasis. Such a culture values innovation in all areas, whether in technology, business, social norms, or human relationships. Firms in the U.S. that can change rapidly, innovate quickly, and respond immediately to market and social pressures are far more successful. Microsoft™ has long dominated the world market in computer operating systems yet are regularly criticized for being slow to change and respond to changing consumer demands, which suggests a high uncertainty avoidance culture within that business. Apple™, on the other hand, has been praised for its innovation and ability to respond more quickly to market demands, suggesting a low uncertainty avoidance culture.

Long-Term Orientation and Short-Term Orientation

People and cultures view time in different ways. For some, the "here and now" is paramount, and for others, "saving for a rainy day" is the dominant view.

The long-term orientation dimension can be interpreted as dealing with society’s search for virtue. Societies with a short-term orientation generally have a strong concern with establishing the absolute Truth. They are normative in their thinking. They exhibit great respect for traditions, a relatively small propensity to save for the future, and a focus on achieving quick results. In societies with a long-term orientation, people believe that truth depends very much on situation, context and time. They show an ability to adapt traditions to changed conditions, a strong propensity to save and invest, thriftiness, and perseverance in achieving results (Hofstede, 2012a).

A long-term culture places significant emphasis on planning for the future. For example, the savings rates in France and Germany are 2-4 times greater than in the U.S., suggesting they are cultures with more of a "plan ahead" mentality (Pasquali & Aridas, 2012). These long-term cultures see change and social evolution are normal, integral parts of the human condition.

In a short-term culture, emphasis is placed far more on the "here and now." Immediate needs and desires are paramount, with longer-term issues left for another day. The U.S. falls more into this type. Congress and the Executive design legislation to handle immediate problems, and it is challenging for lawmakers to convince voters of the need to look at issues from a long-term perspective. With fairly easy access to credit, consumers are encouraged to buy now versus waiting. We see evidence of the need to establish "absolute Truth" in our political arena on issues such as same-sex marriage, abortion, and gun control. Our culture does not tend to favor middle grounds in which truth is not clear-cut.

Expectations for gender roles are a core component of any culture. [This notion of gender and culture is that of the society at large, not an individual aspect]. All cultures understand what it means to be a "man" or a "woman." Masculine cultures are traditionally seen as more aggressive and domineering, while feminine cultures are traditionally seen as more nurturing and caring. Hofstede (2012a) states:

Expectations for gender roles are a core component of any culture. [This notion of gender and culture is that of the society at large, not an individual aspect]. All cultures understand what it means to be a "man" or a "woman." Masculine cultures are traditionally seen as more aggressive and domineering, while feminine cultures are traditionally seen as more nurturing and caring. Hofstede (2012a) states:

The masculinity side of this dimension represents a preference in society for achievement, heroism, assertiveness and material reward for success. Society at large is more competitive. Its opposite, femininity, stands for a preference for cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak and quality of life. Society at large is more consensus-oriented.

A masculine culture like the U.S. highly values winning. We respect and honor those who demonstrate the power and high degrees of competence. Consider the role of competitive sports such as football, basketball, or baseball, and how the rituals of identifying the best are significant events. The 2017 Super Bowl had 111 million viewers (Huddleston, 2017), and the World Series regularly receives high ratings, with the final game in 2016 having the highest rating in ten years (Perez, 2016).

More feminine societies, such as those in the Scandinavian countries, will undoubtedly have sporting moments. However, the culture is far more structured to provide aid and support to citizens, focusing its energies on providing a reasonable quality of life for all (Hofstede, 2012b).

A more recent addition to Hofstede's dimensions of culture, the indulgence/restraint continuum addresses the degree of rigidity of social norms of behavior. He states:

Indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun. Restraint stands for a society that suppresses gratification of needs and regulates it by means of strict social norms (Hofstede, 2012a).

Indulgent cultures are comfortable with individuals acting on their more basic human drives. Sexual mores are less restrictive, and one can act more spontaneously than in cultures of restraint. Those in indulgent cultures will tend to communicate fewer messages of judgment and evaluation. Every spring, thousands of U.S. college students flock to places like Cancun, Mexico, to engage in a week of indulgent behavior. Feeling free from the social expectations of home, many will engage in some intense partying, sexual activity, and relatively limitless behaviors.

Cultures of restraint, like many Islamic countries, have rigid social expectations of behavior that can be quite narrow. Guidelines on dress, food, drink, and behaviors are strict and may even be formalized in law. Some sub-cultures are more restraint-focused in the U.S., a generally indulgent culture. Social norms highly restrain the Amish, but so too can control inner-city gangs. Areas of the country, like Utah with its sizeable Mormon culture, or the Deep South with its large evangelical Christian culture, are more restrained than areas such as San Francisco or New York City. Rural areas often have more rigid social norms than urban areas. Those in more restraint-oriented cultures will identify those not adhering to these norms, placing pressure on them, either openly or subtly, to conform to social expectations.

Hall's Cultural Variations

In addition to these six dimensions from Hofstede, anthropologist Edward T. Hall identified two more significant cultural variations (Raimo, 2008).

Another aspect of variations in time orientation is the difference between monochronic and polychronic cultures. This difference refers to how people perceive and value time.

Another aspect of variations in time orientation is the difference between monochronic and polychronic cultures. This difference refers to how people perceive and value time.

In a monochronic culture, like the U.S., time is viewed as linear, as a sequential set of finite time units. These units are a commodity, much like money, to be managed and used wisely; when time is gone, one cannot retrieve it. Consider the language used to refer to time: spending time, saving time, budgeting time, making time. These are the same terms and concepts we apply to money; time is a resource to be managed thoughtfully. Since we value time so highly, that means:

- Punctuality is valued. Since "time is money," if a person runs late, they are wasting the resource.

- Scheduling is valued. Since time is finite, only so much is available; we need to plan how to allocate the resource. Monochronic cultures tend to let the schedule drive activity, much like money dictates what we can and cannot afford to do,

- Handling one task at a time is valued. Since time is finite and seen as a resource, monochronic cultures value fulfilling the time budget by doing what was scheduled. Compare this to a financial budget: funds are allocated for different needs, and we assume those funds should be spent on the item budgeted. Since time and money are virtually equivalent, in a monochronic culture adhering to the "time budget" is valued.

- Being busy is valued. Since time is a resource, we tend to view those who are busy as "making the most of their time;" they are seen as using their resources wisely.

In a polychronic culture, like Spain, time is far, far more fluid. Schedules are more like rough outlines to be followed, altered, or ignored as events warrant. Relationship development is more important, and schedules do not drive activity. Multi-tasking is far more acceptable, as one can move between various tasks as demands change. In polychronic cultures, people make appointments, but there is more latitude for when they are expected to arrive. David's appointment may be at 10:15, but as long as he arrives within the 10 o'clock hour, he is on time.

Consider a monochronic person attempting to do business in a polychronic culture. The monochronic person may expect meetings to start promptly on time, stay focused, and for work to be completed in a controlled manner to meet an established deadline. Those from a polychronic culture will not bring the expectations of timeliness to the encounter, thus sowing the seeds of intercultural understanding.

The last variation in culture to consider is whether the culture is high context or low context. To establish a little background, consider how we communicate. When we communicate, we use a communication package consisting of all of our verbal and nonverbal communication. Our verbal communication refers to our use of language, and our nonverbal communication refers to all other communication variables: body language, vocal traits, and dress.

The last variation in culture to consider is whether the culture is high context or low context. To establish a little background, consider how we communicate. When we communicate, we use a communication package consisting of all of our verbal and nonverbal communication. Our verbal communication refers to our use of language, and our nonverbal communication refers to all other communication variables: body language, vocal traits, and dress.

In low-context cultures, verbal communication is given primary attention. The assumption is that people will say what they mean relatively directly and clearly. Little will be left for the receiver to interpret or imply. In the U.S., if someone does not want something, we expect them to say, "No." While we certainly use nonverbal communication variables to get a richer sense of the meaning of the person's message, we consider what they say to be the core, primary message. Those in a high-context culture find the directness of low-context cultures quite disconcerting, to the point of rudeness.

In high-context cultures, nonverbal communication is as important, if not more important, than verbal communication. How something is said is a significant variable in interpreting what is meant. Messages are often implied and delivered quite subtly. Japan is well known for the reluctance of people to use blunt messages, so they have far more subtle ways to indicate disagreement than a low-context culture. Those in low-context cultures find these subtle, implied messages frustrating.

Summary

In summary, Hofstede's Dimensions and Hall's Cultural Variations give us some tools to use to identify, categorize, and discuss diversity in communication. Seeing these differences better equips us to manage inter-cultural encounters, communicate more provisionally, and adapt to cultural variations.

In summary, Hofstede's Dimensions and Hall's Cultural Variations give us some tools to use to identify, categorize, and discuss diversity in communication. Seeing these differences better equips us to manage inter-cultural encounters, communicate more provisionally, and adapt to cultural variations.

While intended to show only broad cultural differences, these eight variables also can be useful tools to identify variations among individuals within a given culture. We can use them to identify sources of conflict or tension within a given relationship. For example, Keith tends to be a short-term oriented, indulgent, and monochronic, while his wife tends to be long-term oriented, restrained, and more polychronic. They frequently experience their own personal "culture clashes."

Understanding a few additional concepts is helpful in our effort to become better communicators. One of those is the distinction between race and ethnicity. These terms are used in varied ways; neither is distinctly defined. Race is seen as a social construct that developed based on biological traits. Current findings in genetic studies show those traits are not as distinct as once thought. However, many communities and co-cultures have been based on race, and some developed distinct communication patterns in response to interactions with the dominant culture. People in those communities rely on codeswitching to alter their language use and behavior as they interact within their co-culture or the dominant culture. Ethnicity generally refers to traits associated with the country of birth, which may encompass language, religion, customs, or geographic location. Some people identify closely with their ethnic heritage, especially if their immigrant experience is more recent. Other aspects of cultural identity that play an essential role in understanding intercultural communication are gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, social class, and generation. Students interested in learning more about those components may begin by identifying the values of their own cultures (both dominant and co-cultures).

References for this Section:

Attribution:

"Culture" by Keith Green, Ruth Fairchild, Bev Knudsen, & Darcy Lease-Gubrud, LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY-NC .

Activity - Sample Discussion

1. What is Deep Culture? What is the Iceberg Model? How might you better understand yourself by understanding the culture you grew up in?

- What do you want to learn more about concerning how you are impacted by "deep culture?" Note - this is the influence of family/clans, society/social order (we have pointed you toward Hofested's and Hall's theories), and religion (next week we'll talk more about religion but here is a great resource we'll use next week).

- Answer at least 1 of the following:

- How does the model of the Iceberg Model help us to understand culture?

- How did you react to the video and the section on Human Rights? We challenge you to think about the 2 extremes of "no one can judge" (relativism) and "we must have an absolute judgment" (universalism) - what happens when there are Human Rights violations? If we take a relativistic view, are there even human rights? Yes - hard questions - what do you think?

- Compare the conversation of the video above with what you learned about either the cultural iceberg or deep culture.

Next, as you review what you read, look back to the section called, "Hofstede's Dimensions of Culture." Also look at these links: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/the-usa/ and https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/american-culture

2. How do these 2 websites describe American culture? Do you agree? Relate the materials from the chapter to what you find out from the websites.

3. How can you improve your OWN intercultural communication competence? What did you do last week to test this? What will you do this week?

4. Finally: ADD A PHOTO, video or some symbol that helps us better understand your culture in your post, tell us what it is and why you chose it.

Test it out this week: talk to someone in your family, if you can, about this section in the book [sometimes this can be hard, can you talk to a family friend, someone you grew up with, etc. -- it is often best to do so w/an older person to get a fun perspective. If you need ideas, email Lori].

Key Terms:

- Self

- Worldview

- Identity

- Belief

- Value

- Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

- Cultural relativism

- Universalism

- Ethnocentric

- Echo Chamber

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Deep Culture

- Iceberg Model

- Hofsted's Dimensions of Culture (ALL of them)

- Individualism and Collectivism

- High Power-Distance and Low Power-Distance

- High Uncertainty Avoidance and Low Uncertainty Avoidance

- Long-Term Orientation and Short-Term Orientation

- Masculine Cultures and Feminine Cultures

- Indulgence and Restraint

- Hofstede’s Cultural Variations

- Monochronic and Polychronic

- High Context and Low Context

- Verbal and Nonverbal Communication

- Ethnicity

- Codeswitching

- Race

References

BBC News. (2019, November 24). China's hidden camps. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/resources/idt-sh/China_hidden_camps

Chin-Dahler, J. (2010). Cultural relativism. In J. T. Sears (Ed.), Youth, education, and sexualities: An international encyclopedia (Vol. 1, pp. 137-138). Greenwood.

Constant Foreigner. (2010). Edward T. Hall’s Cultural Iceberg Model. Retrieved from http://www.constantforeigner.com/2010/09/edward-t-halls-cultural-iceberg-model/

Deneen, P. J. (2012). Liberalism: The twilight of the West. Isi Books.

Fuchs, S. (2001). Habitus and cultural observation. In P. Heelas, S. Lash, & P. Morris (Eds.), Detraditionalization: Critical reflections on authority and identity (pp. 154-170). Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Green, K., Fairchild, R., Knudsen, B., & Lease-Gubrud, D. (2022). Hofstede's dimensions of culture. In Intercultural Communication: Open Educational Resource (OER) textbook. Retrieved from https://open.lib.umn.edu/interculturalcommunication/chapter/hofstedes-dimensions-of-culture/

Hussein, R. (2012). Linguistic relativism and cultural relativity in translation. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 41(6), 636-651. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2012.738922

Jersak, R. (n.d.). Individualism and Collectivism and Interpersonal Conflict Potential [Deeper Dive]. Adapted and attributed to Robert Jersak, who attributes Language and Culture in Context: A Primer on Intercultural Communication (2020) by Robert Godwin-Jones.

Krumrey-Fulks, K. (2022). Hofstede's dimensions of culture. In Culture and Psychology: An Open Access Introduction. Retrieved from https://culture-and-psychology.education/hofstedes-dimensions-of-culture/

Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently...and why. Free Press.

Pew Research Center. (2021, August 20). U.S. public continues to have mixed views of the coronavirus vaccine. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/08/20/u-s-public-continues-to-have-mixed-views-of-the-coronavirus-vaccine/

Samovar, L. A., Porter, R. E., McDaniel, E. R., & Roy, C. S. (2017). Communication between cultures (9th ed.). Cengage.

Stewart, J. (2017). Intercultural Communication: Why “Who Are You?” is More Important than “Who Am I?”. John Stewart: Intercultural Communication & Consulting. https://www.johnstewart.com.au/single-post/2017/10/13/Intercultural-Communication-Why-%E2%80%9CWho-Are-You%E2%80%9D-is-More-Important-than-%E2%80%9CWho-Am-I%E2%80%9D

The Critical Thinking Community. (n.d.). Open-minded inquiry. Retrieved from http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/open-minded-inquiry/579

Tucker, M. (1998). Intercultural Communication Competence. Routledge.

United Nations. (2022). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

Worthy, S. L., Lavigne, A. L., & Romero, E. J. (2020). Fundamentals of human communication: Social science in everyday life. McGraw-Hill Education.

Media

Burst. (n.d.). Free stock photos for websites and commercial use. [Photograph]. https://burst.shopify.com/photos/culture-and-diversity-in-people?s=3

Videos:

- https://youtu.be/woP0v-2nJCU

- https://youtu.be/HTp54QwxV8U

- https://youtu.be/TEyMBJOKv3o

Attributions

We are grateful for the use of the following Open Education Resources remixed above as noted and under the Creative Commons 4.0 License.

- "Culture" by Keith Green, Ruth Fairchild, Bev Knudsen, & Darcy Lease-Gubrud, LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY-NC .

- Culture and Psychology by L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Language and Culture in Context: A Primer on Intercultural Communication (2020) by Robert Godwin-Jones.

- 1.3: Cultural Characteristics and the Roots of Culture by Karen Krumrey-Fulks is licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- Intercultural Communication for the Community College by Karen Krumrey-Fulks is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- [Author removed at request of original publisher]. (2016, September 29). The University of M.N. Communication in the Real World. Retrieved December 17, 2021, from https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/front-matter/publisher-information/

"sharing and understanding meaning" or “making common” (Pearson & Nelson, 2000).

As Samovar, Porter, McDaniel, & Roy (2017) explain, “Culture is a set of human-made objective and subjective elements that in the past have increased the probability of survival and resulted in satisfaction for the participants in an ecological niche, and thus became shared among those who could communicate with each other because they had a common language and lived in the same time and place” (p.39).

Perception is more of a process whereby each of us creates “mental images” of the world that surrounds us, that is, of the “world out there” (Green, Fairchild, Knudsen, & Lease-Gubrud, 2018).

According to Gamble and Gamble's definition (1996), "Perception is the process of selecting, organizing, and interpreting sense data in a way that enables people to make sense of our world." (p. 77).

words - verbal communication refers to any communication with grammatical structure. This includes spoken and written language.

“Nonverbal communication is a process of generating meaning using behavior other than words. Rather than thinking of nonverbal communication as the opposite of or as separate from verbal communication, it’s more accurate to view them as operating side by side—as part of the same system” (Communication, 2016, p.165).

Samovar, et. al (2018) add, "we purpose that nonverbal communication involves all those nonverbal stimuli in a communication setting that are generated by both the source and [their] use of the environment and that have potential message value for the source and/or receiver.

“Listening is the learned process of receiving, interpreting, recalling, evaluating, and responding to verbal and nonverbal messages” (Communication, 2016, p.230). Listening is a choice whereas hearing is a physiological action. Further, listening is a skill one can cultivate.

It is through intercultural communication that we come to create, understand, and transform culture and identity. Intercultural communication is communication between people with differing cultural identities (Samavor, et. al).

"Self is a psychological construct that unconsciously and automatically influences our thoughts, actions, and feelings."

Source: Culture and Psychology by L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

"One is born into this world without a sense of self. “Self is not innate, but is acquired in the process of communication with others.”2 With this declaration Wood is saying that through contacts with others, information is accumulated that helps define who you are, where you belong, and where your loyalties rest. Identity is multi-dimensional, since an individual has numerous identities ranging from concepts of self, emotional ties to family, attitudes toward gender, to beliefs about one’s culture. Regardless of the identity in question, notions regarding all your identities have evolved during the course of interactions with others" (Samovar, et al., 2016, p. 26).

According to Darla Deardorff (2004), “Intercultural [communication] competence is the ability to interact effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations, based on specific attitudes, intercultural knowledge, skills and reflection” (p.5).

"Identity is a psychological term used to explain the way individuals understand themselves as part of a social group and are recognized by others as members of the social group."

Source: Culture and Psychology by L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

is how people interpret reality and events, including their images of themselves and how they relate to the world around them” (Samavor et.al., 2017, p. 57).

"Values are broad preferences concerning appropriate course of action or outcome. Reflects our sense of what 'ought' to be."

Source: Culture and Psychology by L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Cultural relativism regards cultural, religious, social, legal, familial, economic, etc. beliefs, practices, and traditions as relative to a given culture (Chin-Dahler, 2010). It is premised on the idea that all aspects of human cultures are relative to one another; that is, all cultures are equally valid and any standard of evaluation, assessment and judgment must be culturally internal only--any cultural criticism must come from persons of that culture.

This is a strong tendency to reflexively view one’s own cultural worldview, beliefs, and practices as superior to those of other cultures.

"A belief is a concept or idea that an individual or group holds to be true. Beliefs represent our subjective conviction in the truth of something -- with or without proof (Samovar, et al., 2017, p. 202).

"Beliefs are the way people think the universe operates. Beliefs can be religious or secular, and they can refer to any aspect of life. For instance, many people in the United States believe that hard work is the key to success, while in other countries your success is determined by fate" (Worthy Lavigne & Romero, 2020).

Source: Culture and Psychology by L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

We only listen or speak inside closed chambers that echo [and amplify] our current beliefs and opinions” (Stewart, 2017).

"The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a milestone document in the history of human rights. Drafted by representatives with different legal and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world, the Declaration was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 (General Assembly resolution 217 A) as a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations. It sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected and it has been translated into over 500 languages" (United Nations, 2022).

Deep culture, "refers to the norms and values that have become entrenched in society over generations. Deep culture is important “because of the institutions of family, church, and state give each individual his or her unique identity” (Samovar and Porter, 2003).

“In 1976, Hall developed the iceberg analogy of culture. If the culture of society was the iceberg, Hall reasoned, then there are some aspects visible above the water, but there is a more significant portion hidden beneath the surface” (www.constantforeigner.com, 2010)

"a preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of themselves and their immediate families only" (Green, et al., 2018).

"Collectivism, represents a preference for a tightly-knit framework in society in which individuals can expect their relatives or members of a particular in-group to look after them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty. A society's position on this dimension is reflected in whether people’s self-image is defined in terms of 'I' or 'we' (Hofstede, 2012a)." (Green, et al., 2018).

"The power distance dimension of culture expresses the degree to which the less powerful members of a society accept and expect power to be distributed unequally" (Green, et al., 2017).

"People in societies exhibiting a large degree of power distance accept a hierarchical order in which everybody has a place and which needs no further justification (Hofstede, 2012a)" - as highlighted in Green, et al., 2017.

"the distribution of power is considered far more arbitrary and viewed as a result of luck, money, heritage, or other external variables" (Green, et al., 2017).