24 Cultural Highlight Section 1 – Explore Somali-American Culture

Cultural Highlight: Somali-American Culture

“I didn’t know I was Black until I moved to America…”– Nadia Mohamed.

Welcome to the Third Unit of the course, where we address the third question: “What are we doing here together?” In Unit One, we asked, “Who am I?” The Second Unit follows the first with the question, “Who are you?” In this Third Unit, we aim to explore contemporary case studies emphasizing how intercultural communication is necessary to our everyday lives.

Our students identify which cultures & co-cultures they would like to learn more about in the initial syllabus quiz and course discussions. One culture that consistently is named is the Somali-American culture. This chapter introduces Somali-American culture. The chapter was reviewed by a Mankato Somali-American educational advisor who used the materials to help train the college staff he works with in Mankato. We were honored to hear that he had done so and asked for additional feedback. We are grateful for his input. We welcome further feedback, interview leads, and information you might want to share.

As we begin publishing this unit, it is time for Mid-term Elections in the United States. There are but eight days until our November 8, 2022, elections. Before writing this unit and integrating materials from other creative commons publications, we knew that many scholars had called the Minnesota Somali-American community one of the most successful co-cultures to integrate into American culture, stressing their use of entrepreneurship, the support given to one another through a Somali lending system and creative mentorhsips, presence in many networks, and their growing political presence. We encourage you to review how other cultures have participated in Minnesota’s and other states’, voting and business sections. This week, we focus on Somali-Americans.

This chapter begins as we introduce two RCTC students who share their stories of coming to America and their experience with Dental Care. This video is not embedded here; it exists on MediaSpace, which does not embed in this ebook). The video was created with Katie in RCTC’s Dental Hygiene Program. This chapter treats five areas: first, a comprehensive introduction to Somali-American Culture; second, we highlight videos and news reports about the integration of Somali-Americans in Minnesota communities (we have included a variety of news and PBS videos that share the stories of individuals in specific Minnesota communities); third, we will explore the notion of culture shock and how culture shock impacts individuals; fourth, we will explore what it means to be a refugee; fifth, we will look toward elections and explore how this co-culture has become involved in American politics.

Learning Outcomes

After reading and considering this unit, students will:

- Learn facts about the Somali and Somali-American cultures

- Distinguish between facts and inferences

- Understand the terms: refugee, asylum seeker, migrant, and immigrant

- Practice paraphrases and perception checking

- Identify the stages of culture shock

Meet Two of Our Peer Student Speakers, Abdullahi & Tammad:

https://mediaspace.minnstate.edu/media/Dental+Interview+C/1_5if28ibj

*Note that this version of PressBooks does not embed MediaSpace videos. The video linked above will be uploaded and embedded via youtube soon. The interview is one hour. It is a nice conversation about their experiences with health and dental care – it is not “edited” but provides insight into their experience.

We sat to chat more about how RCTC students Abdullahi and Tammad experienced “coming to America” and learned more about their perceptions of American culture. To begin, they graciously discussed the Cultural Atlas’ “Do’s and Don’t List” and Somali communication norms.

Abdullahi is from Somalia and moved to the US when he was ten. On their journey, they first lived in Ethiopia after leaving Somalia. Tammad is from Kenya, but her family originated in Somalia. She moved to the United States when she was 12, settling first in Utah. Their interview includes perceptions of the Somalian culture and their lived experiences at Rochester Community and Technical College (RCTC). They also chat about Somali culture’s “Do’s and Don’ts” and their journey to Rochester, Minnesota. Tammad speaks to the differences in her settlement in Utah compared to Minnesota. When she came to Rochester, she learned to read and write when placed in ESL classes. Before that, she sat in a general classroom in Utah. She is grateful she could access an education system better equipped to work with non-English speakers.

Abdullahi traveled with his mom and two older sisters. Ethiopia was the first step, then Rochester. In the video, he shared that they needed to learn English. Even asking for help at the airport proved to be a challenge. He speaks about how he could adapt to American culture–“I adapted here very quickly, as I was young. So I started learning English. It took me probably about a year. After that, it was all good; the younger you are, the more quickly you’ll adapt to it.” Abdullahi and Tammad, like many immigrant children, assumed the roles of interpreters in their families. As you listen to their video, engage in the listening activity. One might make many inferences (guesses or tentative conclusions based on some information while listening). We might infer that their family came to the US as refugees. However, both stated, “We came to the US to reunite with our family.” When listening to stories from other Somali-Americans who settled in Minnesota, many will share that they arrived as refugees. Reading and listening to the stories in this unit will help to understand better how the experiences of Somali immigrants in 2021 might differ from individuals who first arrived in Minnesota during the Somali civil war in the early 1990s as refugees. The term “migrant” refers to a person who leaves his/her country of origin to seek residence in another country (USDHS, 2020).

Optional Activity: Facts vs. Inferences

As we begin this unit, it is helpful to distinguish between a fact (observation or what we take in from our five senses) and an inference (a tentative conclusion based upon some evidence). This activity will help you as we create paraphrases and perception checks later. Students will:

- List three facts from each speaker’s story.

- For each fact, list 3 + inferences you could draw–the goal is to discover how many inferences one could make.

- Check out your inferences.

- Share with your classmates as you can or with others in your living space.

General Information – Somali Migration & Minnesota

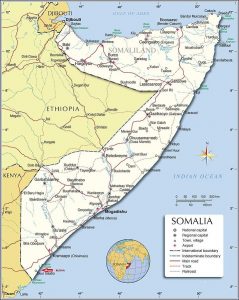

Individuals from Somalia, an East African country located in the Horn of Africa, which shares borders with Kenya, Ethiopia, and Djibouti, have resettled in Minnesota since the 1980s and earlier. With the civil war in Somalia in the 1990s, “VOLGS,” or voluntary agencies, helped individuals settle in the United States. Then, Somalis who settled in Minnesota also assisted new arrivals in their journey to the state (Rutledge, 2018). According to the MN Compass (2021), the total population of Somalis living in Minnesota is approximately 78,046. Of this number, 77.8% of the Somali population resides in the Twin Cities metro area, and 22.2% are in Greater Minnesota.

Diaspora is defined by the Cultural Atlas (2021) as “The movement, migration or dispersion of any people away from their established or ancestral homeland” and is often used to describe the Somali experience. “…Somali-born people living outside their homeland doubled to 2 million between 1990 and 2015,” according to the Pew Research Center. The United Nations notes that “Somalia is one of five countries that produce two-thirds of the world’s refugees; another is Myanmar, which is also a major source of newer refugees in Minnesota” (Rao, 2019).

The majority of the population are ethnically Somali and can trace their genealogy back to common forefathers. Somalis are distinguished by their traditional clan system, Somali language and Sunni Islamic beliefs. Daily life and culture can differ significantly across Somalia as many regions experience varying levels of poverty, governance and safety. Widespread and prolonged displacement has also contributed to diverse understandings of Somali culture. For example, many displaced people and refugees rely on abstract ideas of the Somali identity as they have few or no personal memories of their homeland. Nevertheless, there are certain values that are characteristic to Somalis, these being generosity, hospitality, kinship, respect for the elderly and honour. Broadly, Somalis have also demonstrated a high level of adaptability and entrepreneurialism in the face of adversity.

Syed, Fish, Hicks, Kathawalla & Lee (2020) share, as quoted with permission, an overview of the Somalian diaspora :

The global diaspora of Somalis was triggered by the Somali Civil War, which began in the late 1980s and resulted in an overthrow of the government in 1991 (Kusow, 1994). Though fighting, factions, and governments have ebbed and flowed, there has been ongoing conflict ever since, displacing Somali people across the globe. There are an estimated 2 million Somali refugees worldwide, many of whom are still in refugee camps in Kenya and Ethiopia (Connor & Krogstad, 2016). The U.S. population of Somali Americans is around 150,000, with between 40,000-80,000 living in Minnesota—the location of many of the participants in our study. A section of Minneapolis near the University, Cedar-Riverside, is known colloquially as Little Somalia or Little Mogadishu, named after Somalia’s capital. Somalis have established themselves as part of the Twin Cities community and have increasingly participated in governance, with Abdi Warsame being elected to city council (Williams, 2013) and Ilhan Omar elected first to the Minnesota State House (Minneapolis Public Radio & Xaykaothao, 2016) and subsequently to the U.S. House of Representatives (Witt, 2018).

The Minnesota Chamber of Commerce (2021) also describes the successful migration Somalis have made to Minnesota:

Beginning in the early 1990s, Somali refugees moved to Minnesota fleeing extreme violence as a result of the collapse of the Somali government. As of 2019, Minnesota had the largest Somali population in the U.S. Currently, Minnesota’s foreign-born Somali population totals 36,495,70 the vast majority of whom (~77%) reside in the Twin Cities metro area. While many Somali refugees arrived with limited education, low workforce participation rates and high poverty levels, their situation two decades later has shifted significantly. Poverty levels have dropped, workforce participation has increased, median household income has ticked up and educational attainment has made marginal gains…The percentage of Somali homeowners has also increased. One of the major industries for Somali employment is home health care services, with over 15% of all Somali immigrants in Minnesota working in this industry. Somali workers have also become a vital part of the state’s food manufacturing industry. There are over 2,000 Somali workers in the animal food processing subsector, comprising 11% of total workers. The entrepreneurship rate among Somali immigrants is relatively low and is nearly identical to the rate for the broader foreign-born population statewide.

A table that shares the progress Somalis in Minnesota have made in a remarkable amount of time is shared on the Chamber of Commerce’s website and generated from data from MN Compass.

| Somali Foreign-Born Population, Minnesota Statistics | ||

| 2000 | 2014-2018 | |

| Poverty Rate (%) | 62.9 | 47.6 |

| Workforce Participation Rate (%) | 46.1 | 66.4 |

| Median Household Income (2018 dollars) | 22,035 | 25,000 |

| High School Graduate or More (%) | 54.2 | 56.7 |

| Homeownership Rate (%) | 1.7 | 9.4 |

| Source: MN Compass (data also published on the MN Chamber of Commerce Website) |

“Curious Minnesota” Podcast Addresses – Why Minnesota?

“Minnesota has 52,333 people who report Somali ancestry — the largest concentration of Somalis in Amer ca. This week, we are answering a question from Erik Borg, who wondered about the roots of the Somali inf UX. Host Eric Roper talks with race and immigration reporter Maya Rao about its unfolding. Read the story: www.strib.mn/30ztTvA.” The podcast shares how some Somali individuals came to Minnesota as “secondary refugees.”

Many Somalis also migrated here directly from Africa as primary refugee arrivals, meaning that Minnesota was the first state in the United States where they moved. A group of voluntary agencies, including Lutheran Social Service and Catholic Charities, worked with the federal government to resettle the refugees and help them find housing and jobs. Minnesota was a favored location in part due to the success of resettling Hmong refugees in the 1970s and 1980s. As more Somalis formed a larger community, they drew even more friends and family members who wanted to be among their own (Rao, 2019).

Listen to the podcast: Via Apple Podcasts |Spotify | Stitcher

Finding a Home in Minnesota

If you ask why anyone lives where they do, they mention reasons such as family, jobs, educational opportunities, crime rates, and weather. The following video shares Fartun’s story and the story of the Minnesotans who decided to learn more about Somali culture by involving themselves in her resettlement. When watching the video, to whom do you most relate? How? Have you learned more about someone new to your neighborhood, city, state, or country? Perhaps you have needed to uproot your family life and can relate to Fartun’s experience. Still, others will have experienced moving and perhaps the trauma and fears of individuals fleeing war zones. Taking a dual perspective

When Fartun was just 15 years old, she came to the U.S. as a refugee from Somalia. Soon after settling in Minnesota, she realized that there was a large population of Somali immigrants in her community that were looking for ways to connect to their new home. That’s when she started the Somali-American Women Action Center, with the intention to uplift, protect and educate refugee women to have successful futures. She made a post on Nextdoor looking for an instructor who could help her start a sewing club for the women in her community and met Leslie Mallery, an instructor who vowed to always use, ‘Nextdoor for good.’ (Youtube Description).

Minnesota cities home to many Somalis include Rochester, St. Cloud, and Worthington. For an in-depth analysis of the Somali refugee resettlement, see https://www.unhcr.org/50aa0d6f9.pdf.

While not as common today,

Rochester, Minnesota

Rochester, Minnesota’s Intercultural Mutual Assistance Association (IMAA) helps immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in the process of resettlement. Why Rochester? IMAA’s Executive Director, Armin Budimlic, shared with the MinnPost (2019):

“It has to do with the welcoming environment, the opportunities for jobs and good life here, and there are some well established communities already. In the city of Rochester, the Southeast Asian community has been around for over 30 years. The Somali community is really strong and well established.”

While strong immigrant and refugee communities may draw people to the Rochester area, Budimlic believes that for many people, the range of jobs open to new arrivals is also a major attraction.

“The industries that we have in our region, a lot of them being food processing, hospitality, health care, attract new arrivals for their initial jobs,” he said. “We also have great educational institutions and great a school system that also attracts families.”

While the following video features news coverage dated 2016, it shares the Rochester, MN, immigration story in detail. The report explores the notion of “secondary migrants,” a term often used with Minnesota refugees. The story shares more about this topic. (YouTube Description). “Primary refugees are refugees who are initially resettled in Minnesota. Refugees include refugees, asylees, entrants/parolees, and victims of trafficking. Secondary refugees are refugees who originally resettled to another state in the United States before moving to Minnesota. Currently, there is no systematic way to identify all secondary refugees migrating to Minnesota” (Minnesota Department of Health, 2021).

To define asylee, we turn to the United Nations: “An alien in the United States or at a port of entry who is found to be unable or unwilling to return to his or her country of nationality, or to seek the protection of that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution. Persecution or the fear thereof must be based on the alien’s race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. For persons with no nationality, the country of nationality is considered to be the country in which the alien last habitually resided. Asylees are eligible to adjust to lawful permanent resident status after one year of continuous presence in the United States. These immigrants are limited to 10,000 adjustments per fiscal year” (unhcr.org, 2021).

St. Cloud, Minnesota

St. Cloud has been in the press recently as the community adjusts to migration. “The most recent American Community Survey shows 3,542 residents report Somali ancestry in the 194,000 St. Cloud metro area, which includes Stearns and Benton counties” (Maculus, 2019). St. Cloud has changed its racial profile in recent years.

In keeping with national trends, the St. Cloud is becoming increasingly diverse, U.S. Census data shows. According to U.S. Census 2020 data, St. Cloud-area cities saw growth in almost every census category for race except for white. Sartell and Sauk Rapids are the exceptions, with Sartell’s white population increasing by 13.9%, or 2,100 people, and Sauk Rapids’ by 0.7%, or 79 people. Sherburne County was the only county of the three in the St. Cloud area whose population of white citizens did not decline. Area cities increasingly became home to Black community members. Every major community in the St. Cloud area saw its population of Black citizens grow by more than 100%, with all but Sauk Rapids growing by more than 150% in this category. Waite Park’s population of Black citizens grew by 400% or 1,770 more people. St. Cloud’s population of Black citizens grew by 157.1% or 8,094 more people (Kocher, 2021).

What is it Like Being Somali in St. Cloud? Talia Stump from the City to Country Project talks to locals about what it is like being Somali in St. Cloud, Minnesota – published in May 2019. Before this video, St. Cloud experienced a 2016 Crossroads Mall Shooting. Concerns about retaliation and racism, and anti-Muslim organizing were often on the minds of Somali-Americans in St. Cloud. During this time, some residents voiced their worry about potential terroristic recruitment and activity. These concerns have led many to the polls in more recent years. Asa notes in several videos below that groups are working hard to help bridge community divides based on fear and misinformation.

Overcoming Fear – St. Cloud’s “Dine and Dialogue” Community Education

“Overcoming the Fear” is a theme in news articles and vid os. Some will question, “Why is it my place to educate the dominant culture;” others will say, “It is my opportunity to create a safer home by introducing you to my culture.” The following story shares Hudda Ibrahim’s decision to take action in her St. Cloud, MN community.

“Hudda Ibrahim and her family fled civil war in Somalia for a new life in St. Cloud, Minnesota. She soon discovered that her neighbors were curious about Somali culture, but many were afraid to ask questions. Instead of falling to assumptions and misconceptions, Hudda wanted to encourage a community based on conversation. She started Dine and Dialogue—a program that invited her neighbors to ask questions and get to know each other, all over a home-cooked meal. From hijabs to Sharia law, no subject is off the table. Today, she continues to host this open forum every month, bridging the gap between people and finding a path to compassion through the stomach. The story of America is the story of immigrants. We teamed up with Minnie Driver to share stories of some incredible individuals building a stronger, more united America. Check them all out in our latest series, ‘I Am An Immigrant.’

Willmar, Minnesota

The video below, from 2013, shares the recent transformation rural Minnesota experienced in Wilmar, Minnesota. As discussed below, Minnesota Public Radio featured the integration of multiple cultures in this rural community.

2013: Postcards Somali Culture in Willmar

“Learn about Somali culture in Willmar, MN. Community member, Mohamed Sayid, invites us into his daily life and explains his family traditions. We also hear a tune from Somali musician Aar Maanta and take a trip to the Center Point Mall” (YouTube Description).

Since this 2013 “Post Cards” program aired on MPR, the population of Willmar has grown. Feshir (2019) reports that one-third of the people of Willmar, as of 2019, is 1/3 comprised people of color. Listen to the full story here. Below are highlights from Feshir’s news story:

Deka Ahmed fled civil war-torn Somalia, first to Kenya and then to Arizona in 2009. Willmar, though, is where she wanted to be – a place that welcomed refugees like her and held the promise of a job and a new life.

“There are a lot of Somali people in Willmar that I thought would be helpful,” she said recently through an interpreter. “Neighbors that were from a refugee camp that lived in Willmar – they’re here.”

A city that once seemed an unlikely spot in the country for such a fresh start is now a vital destination for Somali immigrants, joining a Latino population that’s called west-central Minnesota home for decades. People of color now make up about one-third of Willmar’s population of 20,000.

The MPR broadcast discusses the controversy of refugee resettlement. During recent elections, individuals have been more vocal about this issue. It might be tough to determine your response when you find dissent (or hostility). Sometimes when we are unsure what to say next, the best thing is to listen and paraphrase. You might not be ready to comment, or perhaps you have not formed your own opinion yet. In such cases, an honest attempt at paraphrasing can be helpful. Like all advice, remember that verbal and nonverbal communication cues combine in the overall message. Sighing or rolling your eyes while asking, “Did I get that RIGHT?” will certainly not have the calming impact of a sincere question asking for clarity.

Optional Listening Activity: Paraphrasing

This activity focuses on active listening and using the tool called paraphrasing. First, listen to the MPR Story.

Next, listen to Lori share about this activity. The text matches the writing below.

- As a reminder, paraphrasing is a restatement of what you hear. Generally, after listening, you would orally state a paraphrase of the person. In this activity, imagine you will respond to Deka Ahmed and Rollie Nissen, two people interviewed in the MPR story.

- A paraphrase includes three parts:

- First, begin with an I statement:

- I heard

- Second, restate what you heard, focusing on the “facts,” not your inferences. “So I heard you say ____.”

- Finally, ask for clarification

- “Is that correct?” (ask for clarification).

- So, for example, one paraphrase of Deka Ahmed could be:

- “I heard you say you are from Willmar. Is that correct?” This paraphrase is simple; it is just asking about basic information.

- In many cases, you will create a more complex paraphrase.

- “I heard you say that your family lived in the same refugee camp for 30 years, and now you are struggling to reunite with t em? Is that right”

- A paraphrase does not move into a full perception check. That, too, might be an excellent tool to use. In this activity, though, we are only paraphrasing.

- First, begin with an I statement:

- Paraphrases serve at least three purposes:

- 1) to help you understand and retain the message as the listener.

- 2) to help the speaker “hear” what you heard, and

- 3) to provide an opportunity for clarification.

- Now it is your turn!

- First, paraphrase Deka Ahmed’s comments.

- Second, paraphrase Rollie Nissen’s remarks.

- What might be challenging about listening to one another’s comments if Deka Ahmed and Rollie Nissetalked to each other? Why?

Worthington, Minnesota

Stories of success and backlash demonstrate the different perceptions of Somali and other refugee resettlement in smaller towns like Worthington, Minnesota. Michael Miller’s article in the Washington Post drew national attention to Worthington’s changing demographics. He writes, “…immigrant kids fill this town’s school. Their bus driver is leading the backlash” (2011). In addition to the Somali refugee resettlement, Miller notes that thousands of unaccompanied minors have moved to Nobles County, Minnesota.

‘I say ‘good morning’ to the kids who’ll respond to me,’ [bus driver Don Brink said]….’But this year there are a lot of strange kids I’ve never seen before.’ Those children, some of whom crossed the U.S.-Mexico border alone, have fueled a bitter debate about immigration in Worthington, a community of 13,000 that has received more unaccompanied minors per capita than almost anywhere in the country, according to data from the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR)…

…The divide can be felt all over Worthington, where “Minnesota nice” has devolved into “Yes” and “No” window signs, boycotts on businesses and next-door neighbors who no longer speak to each other. A Catholic priest who praised immigrants was booed from the pews and has received death threats.

The driving force behind the defeats has been a handful of white farmers in this Trump-

supporting county, including Brink [the bus driver]. Even as he earns a paycheck ferrying undocumented children to and from school, Brink opposes the immigration system that allowed them to come to Worthington.

‘Those kids had no business leaving home in the first place,’ bus driver Brink said. ‘That’s why we have all these food pantries, because of all these people we are supporting. I have to feed my own kids.’

Now he pulled up to the same high school where he and his wife had walked arm-in-arm as teenage sweethearts, and watched his passengers step down into a stream of dark-haired children, among them a pregnant 15-year-old from Honduras and a 16-year-old girl from Guatemala who’d arrived months earlier….[In six years], more than 400 unaccompanied minors have been placed in Nobles County — the second most per capita in the country, according to ORR data.

Optional Reflection & Application Activity. Please visit the “Comments” associated with the Washington Press Article discussed above.

Optional Reflection & Application Activity. Please visit the “Comments” associated with the Washington Press Article discussed above.

- Discover three different perceptions of the community in three separate comments.

- What might additional details help to build a more complex perception?

- Create three perception checks you could give the three people who made the comments you analyzed.

More on Somali and Somali-American Experiences in Minnesota

CASE STUDY: Somali and Somali American Experiences in Minnesota

from MNOPEDIA (creative commons)

The following information in this textbox is shared in its entirety from MNOPEDIA (Wilhide, 2021)

MIGRATION AND RESETTLEMENT

Since the civil war began, the United Nations has reported that more than one million Somalis have left the country as refugees or asylees. There are 1.5 million people internally displaced within Somalia. The United States began issuing visas to Somali refugees in 1992. For those who received a visa, the decision to leave families and homes in East Africa was painful, but many did leave and resettled in the United States.

Somalis started arriving in Minnesota in 1992. Some came as refugees, while others arrived as immigrants through the sponsorship of family members or relocated to Minnesota from other parts of the United States. Refugee resettlement agencies like the International Institute of Minnesota and World Relief Minnesota, non-profit, faith-based service organizations like Lutheran Social Services and Catholic Charities, Somali-led organizations like Somali Family Services and the Confederation of Somali Community in Minnesota, and Somali individuals and families helped facilitate the migration and resettlement of Somalis in Minnesota.

In 2018, Minnesota hosted one of the largest Somali communities in the Somali diaspora. The exact number of Somalis living in the state is difficult to determine, and estimates range from 30,000 to 100,000. Census data from 2010 offered an estimate of 57,000. Most Somalis in Minnesota live in the Twin Cities metropolitan area, while others have settled in smaller towns throughout the state. Many Somalis have chosen Minnesota because of its social networks, educational and employment opportunities, and access to services. Somalis also cite Minnesota’s high standard of living and a reputation for martisoor (hospitality).

Somalis arrived in Minnesota with social and cultural resources to help them adapt. They have built extensive social and professional networks that have helped them find housing, employment, and educational opportunities. They have faced challenges, too, including separation from family and friends, learning English while preserving their native language, and maintaining cultural and religious practices in a multicultural society. Some struggle to obtain housing that meets their needs, find jobs that meet their skill level, and succeed in secondary and higher education systems.

SOMALI EXPERIENCES IN MINNESOTA

Oral history plays a vital role in telling the history of the Somalis in Minnesota {the Somali language was not systematically written down until 1972}. Their stories show Somalis’ everyday experiences, individual agency, and decision-making processes that left their East African homes, journeyed to America, and made new homes in Minnesota. Fortunately, the Minnesota Historical Society has gathered several oral histories from Somalis in Minnesota (quoted below), so public audiences can learn about their experiences.

Leaving Home

Like many Somalis, Aden Amin Awil and his family fled their home in the early 1990s when conditions reached a low point. “There was looting everywhere in the cities,” Awil later recalled. “We did not have services, education, health, communication, infrastructure of any kind.” His family and many others sought safety in nearby countries, hoping the civil war would end quickly.

While Awil headed to a city in Ethiopia, others fled to refugee camps in Kenya. There, they received food and shelter, though there were often shortages. Many faced desperate conditions in the camps involving starvation, rape, and violence. Others sought refuge in Nairobi, Kenya, but also experienced difficulties.

The Somalis in Minnesota represent a cross-section of Somali society—they were teachers, civil servants, nomads, farmers, entrepreneurs, students, professors, and merchants in their homeland. They represent all regions of Soma ia. Abdisalam Adam came with a student visa in 1990 and first lived in Washington, DC. “I used to hear about Minnesota as a very cold state, the snow and the ice…But also, I heard that it’s a state that’s very welcoming. Its people are friendly. It has good education. It has very understanding people who, you know, are tolerant of other cultures and values and so on. When I came here, I did find all that to be true.”

Mohamed Jama’s family left Mogadishu in the late 1980s as violence escalated. “The country was not stable. There was a fear of young males like me getting recruited to fight against…to be a part of the coup, that is, a child soldier…My mother did not want to see me end up like that…she had to find a safer place for her young people to grow up.” Jama’s family fled to Nairobi, and in 1992 they were granted resettlement in the United States. Mohamed’s family was one of the first to arrive in Minnesota and settle in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis.

Hared Mah and his family survived the civil war in Somalia for several years but eventually fled to Kenya in 1999. Though they lived in Nairobi as Somali refugees, they faced harsh treatment by Kenyan police and found it challenging to get an education or employment. Mah’s father obtained a visa to the United States, and in 2001 he was able to sponsor Hared, his sister, and his mother for resettlement in Minnesota.

Most Somalis ultimately chose to settle in the Twin Cities because of employment, housing, services, and education opportunities. Early on, however, some came for jobs in the agricultural and meat processing industries, many of which offered entry-level positions and did not require English proficiency. Some of the first Somalis in Minnesota settled in Marshall to pursue employment at a turkey processing plant.

The Cedar-Riverside neighborhood hosts the largest concentration of Somalis in Minnesota and has become a hub for the Somali community because of its many organizations, mosques, and businesses. The Confederation of Somali Community in Minnesota was established in the neighborhood in 1994 and was the first Somali organization to help refugees resettle in Minnesota.

Rebuilding Lives

Leaving homes in East Africa, traveling thousands of miles, and arriving in Midwestern America could be a bewildering experience. As Saida Hassan, a young refugee, explains, “It was hard for me to come here, and when I stepped off the plane into America I knew that everything was gonna change; I knew that nothing was gonna be the same. It was hard for me, you know, seeing all these different people.”

Somali refugees share experiences with earlier immigrants. However, recent refugees have faced a different adjustment process because they have dealt with multiple traumas – they have survived a civil war, life in refugee camps, and resettlement in a country with very different cultural and religious traditions.

Like many immigrants, Somalis faced language and cultural barriers when they arrived in Minnesota. Many came with proficiency in multiple languages: Somali, Arabic, and sometimes Swahili, French, or Italian. But gaining English proficiency has been challenging and made the transition to America difficult. As a Somali refugee, Hared Mah explains, “Everything you need, you have to ask for…You have to ask someone to translate, so it was kind of like you cannot do anything. You are like a little kid that cannot even speak.”

Somali elders have had more difficulties learning English than Somali youth exposed to English at school and through popular media. Because of this language barrier, many Somali elders struggle with isolation, a significant obstacle to adjusting to a new culture.

Older Somalis are also concerned that Somali youth are losing their language skills. They understand, however, that English surrounds them in American society. Somali families have addressed this concern by creating charter schools catering to the Somali community.

Being Muslim in Minnesota

Many Somalis see their Islamic faith as integral to Somali identity. Somalis make up one of the largest Muslim communities in Minnesota. This state has been comprised mainly of Protestant (especially Lutheran) and Catholic communities for most of its history. When Somalis arrived in the 1990s, many in Minnesota were unfamiliar with Islam or the religious practices of Muslims. There has been a long period of adjustment as Somalis have sought to educate Minnesotans about Islam, and as Minnesotans have gained more familiarity with Muslim religious practices.

The word “Islam” means “submission to the will of God.” Followers of Islam are called Muslims. Muslims are monotheistic and worship one, all-knowing God, who in Arabic is known as Allah. Followers of Islam aim to live a life of complete submission to Allah (History.com Editors, 2018).

Somalis have faced barriers to practicing their faith in Minnesota. For example, Muslims pray five times a day and fast from sunrise to sundown during the holy month of Ramadan. Finding space for daily prayers at school or work is a recurring challenge for many Muslims. In addition, carrying out ablution—the ritual of cleansing one’s hands and feet before daily prayers—requires space and time. Such practices are problematic in a society not used to accommodating prayer in schools or workplaces.

Muslims are expected to avoid pork and alcohol and eat halal foods (processed according to Islamic l w). The number of halal markets and restaurants is growing, but pork remains a staple in the Midwestern diet. Bars and liquor stores form part of the social life of every neighborhood.

The norm among Somali Muslim women is to dress modestly and wear the hijab or head covering. Many Somali women choose to wear the hijab but have faced religious discrimination at school, work, and in public. Other Somali women have decided not to wear the hijab.

Increasingly, Minnesotans have tried to accommodate the needs of Somalis and other Muslims in schools and the workplace. Many public schools have removed pork from their food menus or have provided options for those students who cannot have pork products. Many schools and workplaces have tried to accommodate the practice of daily prayers by giving space for students and employees to pray during the day. Since the founding of Dar Al-Hijrah, the first mosque in Minnesota, in 1998, the number of mosques has grown to accommodate the growing Somali population.

The events of 9/11/2001 affected Somalis in Minnesota. Fear of terrorism led the US government to scrutinize anything it believed had connections to the terrorist network Al-Qaeda. Money-wiring businesses in the Twin Cities were closed because of government suspicion of links to terrorist groups in Somalia. Many Somalis used these wire transfer businesses to send funds to family members living in Somalia or Kenyan refugee camps. They did not know about any links to a terrorist network.

The possible connection of a wire service to Al-Qaeda, described in a 2001 Minneapolis Star Tribune article, might have even spurred attacks on a few Somalis in Minneapolis. The Somali community was outraged at these allegations and quick to assure the Minnesota community that it did not support the mission of Al-Qaeda.

The US government has continued investigating possible links between Somalis in Minnesota and the terrorist groups Al-Shabaab and Islamic State (ISIS). From 2007 to 2008, approximately twenty young Somali men left Minnesota and returned to Soma ia. The reasons they left remain unclear (many think it was to fight against Ethiopian troops), but the twenty young men most likely were recruited to join Al-Shabaab.

Recruitment has been an ongoing tragedy for many Somalis in Minnesota as they have struggled with losing sons, nephews, and friends while the FBI has investigated the situation. In 2016, nine young Somali-American men pleaded guilty to conspiring to fight for the terrorist group ISIS in Syria. The trial was the largest of its kind in the United States and left the Somali community deeply troubled by the radicalization of Somali youth in Minnesota.

Most Somalis strongly disagree with the ideas and practices of violent extremists and terrorist organizations like Al-Shabaab, Al-Qaeda, and ISIS. The majority of Somalis advocate for Islam as a religion of peace. Several Somali faith leaders and organizations have supported de-radicalization initiatives and programs among Somali American youth.

Somalis have created organizations and networks to help each other navigate their way in Minnesota. They have also used a wide array of social, economic, and health resources available through state, county, and community organizations. Some have begun to purchase homes as they decide to settle in Minnesota. Islamic law, however, restricts Muslims from paying interest on loans, a significant obstacle for Somalis who need mortgages to buy a house. A Somali-led organization, the African Development Center, provides interest-free loans for Somalis and other Muslim Minnesotans to start businesses and buy homes.

Somali youth are pursuing educational opportunities in many higher education institutions. The Somali Student Association at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities serves over 500 Somali students on its campuses. Many Somali youths see education as a way to achieve a better quality of life.

Many Somali adults could not transfer their degrees or professional training to jobs in the Minnesota economy. However, some have participated in the education, health, and transportation sectors. The Somali business community has earned an international reputation for successful, small-scale entrepreneurship.

Balancing Cultures

As Somalis adjust to their lives in Minnesota, many are concerned about what parts of Somali culture they will hold on to and what elements of American culture they will adopt. However, as Maryan Del sees it, “I have two homes—my American home and my Somali home. I have two cultures and two languages. This is part of my life because I grew up having my life here.”

There is much concern about a growing divide between Somali elders and Somali youth. Somali youth feel like they are combining American and Somali cultures. As Mohamed Jama, a Somali youth leader, said, “Most of our young people are not losing culture, but they are entwining with the culture.”

However, both Somali elders and Somali youth recognize the importance of Somali cultural preservation. As Sumaya Yusuf, a young Somali woman, explains, “We have to keep that part of our traditions very important. I’ll be the first to admit that I can’t speak Somali as well as I would like to. I would love to learn.”

As Somalis hold on to their traditional culture, they also embrace opportunities to get involved in American society through joining or creating civic, cultural, and political organizations. Younger Somalis are running for public office. Abdi Warsame joined the Minneapolis City Council in 2013, and in 2016, Ilhan Omar became the first Somali-American elected to the Minnesota Legislature.

Staying Connected to Somalia

As Somalis focus on their lives in Minnesota, they also maintain transnational connections to Somalis living in Somalia and other parts of the world. Many send remittances to family members that play an essential role in Somalia’s economy. Somalis also travel around the world to visit displaced relatives. They maintain connections with other Somalis in the diaspora as they reunite their families and help each other in places like Europe, North America, and Australia.

Somalis in Minnesota are deeply concerned with how to unify and rebuild Somalia after decades of political, social, and economic instability. Some have returned to help, while others have participated in rebuilding the nation’s political, social, and economic infrastructure. For example, the Minnesota-based Somali organization Somali Family Services (SFS) built the Puntland Library and Resource Center in northern Somalia. Thousands of people in the region use the library, and SFS uses the space to provide training and workshops for civil society organizations.

Even as they build new lives in Minnesota, many Somalis hope that peace will return to Somalia. Some plan to return. However, as of 2018 [and still in 2022], the Somali national government struggles to establish a safe and secure country. Somalia’s desperate social, political, and economic conditions {including severe life-threatening drought and starvation} prevent many Somalis from returning there. Many try to bring family members to Minnesota as they decide to make the state their new home.

Attribution: MNOPEDIA; First published: February 27, 2018; Last modified: July 15, 2021

Minnesota Needs Immigrants

The Minnesota Chamber of Commerce further states that for economic security, Minnesota needs immigrants. “Minnesota’s demographics are shifting, and the population is quickly aging. According to the State Demographer, deaths will outnumber births by the early 2000s. For Minnesota to experience meaningful population growth in the future, it will need to come from migration to the state” (2021).

In 1994 there were no significant Somali businesses to speak of in Minnesota. Today [2008 when the article was written], we estimate that there are over 550 Somali-run and managed businesses in this state. It is an amazing accomplishment for people who have been displaced by war and forced to leave their families, homes, and assets behind. The stories of Somali entrepreneurs inthe Twin Cities are unparalleled and unique” (Samatar, 2008).

Minnesota’s Macalester College publishes Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies, where you can gain more detailed scholarly information about Somali and Somali-Amerian culture.

What the MN Chamber of Commerce Concluded

The major findings of this report demonstrate the following:

- Minnesota needs immigrants. Absent their arrival, our population would have declined since 2001, with Minnesota residents moving to other states.

- Immigrants link Minnesota to the world economy and make valuable and meaningful contributions to our state as employees, entrepreneurs, consumers, and taxpayers.

- Immigrant entrepreneurship in Minnesota lags behind the rest of the nation. In a “homegrown” economy, entrepreneurship is crucial for new businesses. Building systems that support immigrant entrepreneurs is vital to our current and long-term economic success.

- The nature of our immigrant population varies by region. The immigrant population in the Twin Cities region is vastly different from those in greater Minnesota, both in number and percentage. The Central area, for example, has experienced faster immigrant population growth over the past ten years than other parts of the state.

- Many of Minnesota’s most important industries have a solid immigrant presence. Without immigrant workers, key sectors such as agriculture, health care, and food manufacturing could not be as successful in the state.

- Over time, immigrants are upwardly mobile on multiple fronts, including improved poverty, unemployment, and homeownership rates. While there are costs for supporting foreign-born populations when they first arrive, these costs diminish as subsequent generations assimilate and gain economic success.

*Source: The economic contributions of immigrants in Minnesota: Executive summary and introduction. Minnesota Chamber of Commerce. (2021, March 3). Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.mnchamber.com/blog/economic-contributions-immigrants-minnesota-executive-summary-and-introduction.

Chronology

https://www.mnopedia.org/somali-and-somali-american-experiences-minnesota

- 1991 – Decades of violent civilian repression ousts Somalia’s president. Civil war begins as clan leaders and politicians fight to control Mogadishu and the rest of the country. Thousands flee to refugee camps and cities in neighboring countries.

- 1991–1992 – Drought, clan-based violence, and political chaos create a famine that kills more than 200,000 Somalis, many are children. The US leads Operation Restore Hope, a U.N.-sanctioned mission to provide humanitarian aid to Somalia’s most devastated areas.

- 1992 – The first Somali refugees arrive in Minnesota. Some resettle in the Twin Cities; others move to Minnesota from other states. In the summer, a group of Somali men travels from Sioux Falls and San Diego to Marshall, seeking jobs at turkey-processing plants.

- 1994 – The Confederation of Somali Community in Minnesota is established in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis to help resettle Somali refugees. CSCM is the oldest Somali organization in Minnesota.

- 1998 – Dar Al-Hijrah, a mosque established in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood, is the first Somali mosque in Minnesota.

- 2001 – 9/11 led to increased scrutiny and interrogation of Somalis throughout the diaspora, including Minnesota. The Somali community in Minnesota rejects Islamic terrorism and promotes Islam as a religion of peace.

- 2003 – Somali-American Hussein Samatar founds the African Development Center in Minneapolis to provide interest-free loans to Muslim entrepreneurs and homeowners, including Somalis. The ADC soon expands to include offices in Rochester and Willmar.

- 2005 – Karmel Mall, one of the biggest Somali malls, opens in Minneapolis. It houses more than 100 businesses that cater to the Somali community, selling everything from Somali food and clothing to phone cards and prayer rugs.

- 2008–2009 – A small group of young Somali men returned to Somalia recruited by the terrorist organization, Al-Shab ab. Many die or are never heard from again. The FBI investigates radicalization among Somali Minnesotans as the community struggles with losing these young men.

- 2010 – Hussein Samatar is elected to the Minneapolis School Board. He was the first Somali-American elected to public office in the United States.

- 2012 – The first parliamentary elections were held for a permanent and internationally recognized Somali federal government. While some Somalis return to Somalia hoping to reunite with family, most stay in Minnesota and continue to build their lives there.

- 2013 – The Somali Museum of Minnesota, dedicated to preserving Somalia’s traditional culture, opens in Plaza Verde on East Lake Street in Minneapolis.

- 2013 -Abdi Warsame is the first Somali American elected to the Minneapolis City Council.

- 2016 – Nine young Somali men plead guilty or were convicted of conspiracy to join the Islamic State (ISIS). Their trial brought scrutiny to radicalization in the Somali American community. Local leaders continue to help Somali youth adjust to life in the US.

- 2017- Ilhan Omar is the first Somali-American elected to the Minnesota State Legislature.

Attribution:

Somali and Somali American experiences in Minnes ta. MNopedia. (n. .). Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.mnopedia.org/somali-and-somali-american-experiences-minnesota. Published originally with a creative commons license.

More about Somalia

The United Nations offer the Following Facts about Somalia (See UN Country Facts for more information)

Geographic: Location

Geographic: Location

Eastern Africa, bordering the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean, east of Ethiopia

Geographic: Longitude & Latitude

10 00 N, 49 00 E

Geographic: Area

total: 637,657 sq km water: 10,320 sq km land: 627,337 sq km comparatively: slightly smaller than Texas

Geographic: Climate

Principally desert; December to February – northeast monsoon, moderate temperatures in the north and very hot in the south; May to October – southwest monsoon, torrid in the north and hot in the south, irregular rainfall, hot and humid periods (“tangambili”) between monsoons

Economic: GDP by sector

agriculture: 65% industry: 10% services: 25% (2000 est.)

People & Culture: Population

8,025,190; This estimate derives from the Somali government’s official census in 1 975. Population estimates in Somalia are complicated by many nomads and by refugee movements in response to famine and clan warfare (July 2003 est.)

People & Culture: Ethnic Groups

Somali 85%, Bantu and other non-Somali 15% (including Arabs 30,000)

People & Culture: Languages

Somali (official), Arabic, Italian, English

To better understand Somalia’s geographic attributes, visit Open Street Map: Somalia.

Somali Cultural Descriptions from the “Cultural Atlas”

Nina Evason (2019) shares:

One’s genology is a defining factor in Somali culture. Society is characterised by a large extended family clan system. Membership to clans is determined by paternal lineage (through the father). People can trace their lineage back for generations and are generally able to determine how they are related to a person, how they should address them and pay respect to them, simply from learning their name and kjXZA clan membership.

There are four major clans in Somalia (Darod, Hawiye, Dir and Rahaweyn) and a number of medium-to-small groups. Each clan can be further divided into numerous sub-clans that can consist of tens of thousands of people alone. Within these sub-clans, there are even more group divisions based on kinship alliances of smaller extended families. The group divisions within the clan system are not necessarily based on geographic differences. It is common for a variety of sub-clans to live within the same area.5

Examine the information below to understand Somali cultural greetings, language, and the “do’s and don’ts of Somali culture.

Do’s and Don’ts of Somali Culture as Reported by The Cultural Atlas

Do’s

- Try to refer precisely to the Somali nation, nationality, or culture rather than “African.” It is appreciated when foreigners recognize that Somalia is culturally distinct from the rest of Africa.

- Show respect to elders in all circumstances and situations; age indicates wisdom, knowledge, and experience.

- Repeat any offer multiple times to show that you are genuine and not just polite. For example, if you offer to drive a Somali home, they are likely to initially decline the gesture out of politeness even if they have no other form of transport. Instead, insist that you want to help.

- Ensure you are respectful and modest, and follow the correct etiquette when visiting a Somali person’s home (see Etiquette).

- Remember to show genuine personal interest in your Somali counterpart. Somalis generally see everyone as their friends (instead of acquaintances) and will be prepared to quickly open up their lives to you personally after the first meeting. Treating your friendship lightly or ignoring them when present can be exceedingly hurtful and offensive (see ‘Social Life‘ in Core Concepts).

- It is advisable to exercise sensitivity talking about their homeland and migration journey. Most Somalis hold their country and people very close to their hearts. However, be aware that some may still experience trauma associated with memories of their time in Somalia.

- Expect to be asked about your private life and well-being if you show strong outward emotions (e.g., anger, sadness, excitement). Somali society is very communal, and people often want to help you when you are in distress or share your happiness.

Don’ts

- Do not openly criticize the religion of Islam, Somali cultural practices, or their way of life. Somalis are generally open people, but such remarks are unlikely to be appreciated.

- Avoid asking questions that assume Somalis are uneducated, uncivilized, or impoverished, such as “Do you have the internet in Somali ?”. Most Somali refugees and migrants living in English-speaking countries are skilled, educated, urbanized, and familiar with the technologies of the developed world.

- Avoid offering opinions on clan politics and rivalries. Clan issues can be emotionally charged. It can be very disruptive to get caught up in clan dynamics or perceived as taking sides. It is best to listen if the topic is raised (see ‘Political Sensitivities‘ in Core Concepts).

- Do not blame Somalia’s conflict and political turmoil on the Somali people and culture. Remember that foreign interference played a significant role in creating the conditions for the civil war, and refrain from voicing your view unless asked.

- Avoid referring to Somalia as a “failed state.” Such a description discounts that the situation in Somalia has improved markedly over the past few years and perpetuates the view that the country is a lost cause.

- Do not assume that Somali Muslims follow a conservative, fundamentalist interpretation of Islam. The actions and beliefs of extremist groups such as Al-Shabaab do not represent the religious interpretations of ordinary Somali people (see Religion).

- Do not make jokes that Somali refugees are criminals or pirates. Such stereotypes are ill-informed and can be offensive.

Somali Greetings

Shared with permission from the Cultural Atlas (Evason, 2019).

Greetings

- It is polite to stand up to greet people out of respect, especially those older than you.

- The everyday casual greeting in Somali is “See tahay” (How are you ?). People may also say, “Is ka warran?” (What’s the news?) or “Maha la shegay?” (What are people saying ?). These phrases mean simply, “Hello/How are you.”

- To use the traditional Islamic greeting, say “As-Salam Alaykum” (May peace be upon you). This is often an appropriate greeting when meeting someone older than you. The correct response is “Wa’ alikum assalaam.” (And peace be upon you).

- Handshakes are a common form of greeting among men. Somali handshakes between men can be pretty firm.

- People generally do not touch those of the opposite gender during greetings unless they are a close family member. Therefore, men should wait until a woman extends her hand before extending his hand for a handshake.

- In very casual settings where people are familiar with one another, handshakes may not even be necessary.

- Women generally greet informally, hugging one another and kissing on the cheek. In some regions, women may shake one another’s hands and then kiss the hand they have touched.

- Refer to people by their first name alone. It is rare to use people’s last names or formal titles (see Naming).

- Somalis may refer to adults that they respect and feel a closeness to by a title such as “Adeer” (uncle), “Eeda” (paternal aunt), or “Habo/Habaryar” (maternal aunt) followed by the person’s first name. To use these titles, one does not have to be related to the person.

Read More About Somali Culture at the Cultural Atlas Website Links Below:

Read More About Somali Culture at the Cultural Atlas Website Links Below:

- Religion

- Family

- Naming

- Dates of Significance

- Etiquette

- Do’s and Dont’s

- Communication

- Other Considerations

- Business Culture

Attribution

Shared with written permission from the Cultural Atlas

Evason, N. (20 9). Somali cult re. Cultural At as. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/somali-culture/somali-culture-core-concepts#somali-culture-core-concepts.

Additional Resources on Somali Culture

Simple Somali Phrases to Practice:

Learning Names

Among the most straightforward ways of showing respect is pronouncing another’s name correctly. Below are some resources for learning Somali names:

Beyond Stereotypes

Ifrah Mansour, “I am a Refugee”

As a reminder, communication is most simply defined as “making common” or “sharing and understanding a common message” by many authors and Communication researchers. However, in our globalized society, more barriers exist to what we believe to be “common” messages or interpretations of messages. As noted before, communication messages are verbal (words both oral and written) and nonverbal (everything other than words – such as body both explicit (overtly planned) and implicit (more subtle). Perhaps the most significant barriers to healthy intercultural communication include ethnocentrism and stereotypes. Somali-American and Minnesota-based artist Ifrah Mansour shares the problem of ethnocentrism through the award-winning performance of her poem, “I Am A Refugee,” accompanied by Sultans of String. For ideas on incorporating this poem and performance in a classroom, see https://www.tpt.org/resource/ifrah-mansour-multimedia-artist/.

Who is a Refugee?

In this poem, the term “refugee” is used. You might wonder what distinguishes a refugee from an “immigrant” or other newcomers to a culture. Immigrants are “People who voluntarily move to a country of which they are not natives who take up permanent residence. Merriam Dictionary (2021) helps us better understand the confusion between immigrant and emigrant: “The main difference is that “immigrant” refers to the country moved to, and “emigrant” refers to the country moved from…While the words have been used interchangeably by some writers over the years, immigration stresses entering a country, and emigration stresses leaving.”

Another term to consider is diaspora. “Diaspora refers to a population that shares a common heritage scattered in different parts of the world…The key difference between diaspora and migration is that in diaspora the people maintain a very strong tie to their homeland, their roots, and their origin, unlike in migration” (Differencebetween.com 2016).

The following text boxes share definitions from three entities: the United Nations, an advocacy group, Amnesty International, and the US Federal Government.

Related Definitions

Defined by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Asylum, Asylum-seeker, and Refugee

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) office offers a glossary of terms, including a refugee definition.

- Asylum: “The grant, by a State, of protection on its territory to persons from another state who are fleeing persecution or serious danger. Asylum encompasses a variety of elements, including non-refoulement {no one should be returned to a country where they would face torure, cruelty, and face degrading treatment} permission to remain on the territory of the asylum country and humane standards of treatment” (unhcr.org, 2021).

- Asylum-Seeker: “An individual who is seeking international protection. In countries with individualized procedures, an asylum-seeker is someone whose claim has not yet been finally decided on by the country in which the claim is submitted. Not every asylum-seeker will ultimately be recognized as a refugee, but every refugee was initially an asylum-seeker.”

- Refugee: “A person who meets the eligibility criteria under the applicable refugee definition, as provided for by international or regional instruments, under UNHCR’s mandate, and/or in national legislation” (unhcr.org, 2021).

Amnesty International Offers Definitions

Similar definitions are found with Amnesty International:

- “A refugee is a person who has fled their own country because they are at risk of serious human rights violations and persecution th re. The risks to their safety and life were so great that they felt they had no choice but to leave and seek safety outside their country because their own government cannot or will not protect them from those dangers. Refugees have a right to international protection” (AmnestyInternational, 2021).

- “An asylum-seeker is a person who has left their country and is seeking protection from persecution and serious human rights violations in another country, but who hasn’t yet been legally recognized as a refugee and is waiting to receive a decision on their asylum claim. Seeking asylum is a human right. This means everyone should be allowed to enter another country to seek asylum” (Amnesty International, 2021).

- Amnesty International further explains the complexity of defining who ia migrant is.

- There is no internationally accepted legal definition of a migrant. Like most agencies and organizations, we at Amnesty International understand migrants as people staying outside their country of origin, not asylum-seekers or refugees. Some migrants leave their country because they want to work, study, or join a family. Others feel they must leave because of poverty, political unrest, gang violence, natural disasters, or other serious circumstances. Many people don’t fit the legal definition of a refugee but could nevertheless be in danger if they went home. It is essential to understand that, just because migrants do not flee persecution, they are still entitled to have all their human rights protected and respected, regardless of their status in the country they moved to. Governments must protect all migrants from racist and xenophobic violence, exploitation, and forced labour. Migrants should never be detained or forced to return to their countries without a legitimate reason (Refugees, asylum-seekers ,and migrants, 2021).

Defintions from the United States Government to Consider

In the United States, the following distinction is made by the Department of Homeland Security:

A refugee is a person outside his or her country of nationality who is unable or unwilling to return to his or her country of nationality because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. An asylee is a person who meets the definition of refugee and is already present in the United States or is seeking admission at a port of entry. Refugees are required to apply for Lawful Permanent Resident (‘green card’) status one year after being admitted, and asylees may apply for green card status one year after their grant of asylum (Department of Homeland Security, 2021).

Language can become confusing when looking to learn more about what it means to be a newcomer. When researching the most legal definition of “immigrant,” the US Department of Homeland Security notes their terms page, “see permanent resident alien,” and no other comments. They then define a Permanent Resident Alien as:

An alien admitted to the United States as a lawful permanent resident. Permanent residents are also commonly referred to as immigrants; however, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) broadly defines an immigrant as any alien in the United States, except one legally admitted under specific nonimmigrant categories (INA section 101(a)(15)). An illegal alien who entered the United States without inspection, for example, would be strictly defined as an immigrant under the INA but is not a permanent resident alien. Lawful permanent residents are legally accorded the privilege of residing permanently in the United States. They may be issued immigrant visas by the Department of State overseas or adjusted to permanent resident status by the Department of Homeland Security in the United States (Department of Homeland Security, 2021).

The quote above necessitates defining “alien.” The exact definition of the terms sheet states, “Alien – Any person not a citizen or national of the United States (Department of Homeland Security, 2021).”

Culture Shock

After reading the stories of migration to Minnesota, you will notice that many of the individuals featured in this unit share similar experiences in their acculturation process. The following section, shared through a Creative Commons license agreement, briefly outlines culture shock.

Culture Shock

Culture Shock

As part of the acculturation process, individuals may experience culture shock when they move to a different cultural environment. It can also describe the disorientation we feel when exposed to an unfamiliar way of life due to immigration to a new country, a visit to a new country, moving between social environments (e.g., moving away for college), or transitioning to another type of life (e.g., dating after divorce). Common issues associated with culture shock include loss of status (e.g., from a provider to unemployed), unfamiliar social systems and social norms (e.g., agencies rather than extended kin networks), distance from family and friends, information overload, language barriers, generation gap, and possibly a technology gap. There is no way to prevent culture shock because everyone experiences and reacts differently to the contrasts between cultures.

Culture shock consists of at least one of four distinct phases:

Honeymoon

During this period, the differences between the old and new cultures are seen in a romantic light. For example, after moving to a new country, an individual might love the new food, the pace of life, and the locals’ habits. Most people are fascinated by the new culture during the first few weeks. They associate with individuals who speak their language and are polite to foreigners. Like most honeymoon periods, this stage eventually ends.

Negotiation also called “Tension.”

After some time (usually around three months, depending on the individual), differences between the old and new cultures become more apparent and may create anxiety or distress. Excitement may eventually give way to irritation, frustration, and anger as one continues to experience unpleasant events that are strange and offensive to one’s own cultural attitude. Language barriers, stark differences in public hygiene, traffic safety, food accessibility, and quality may heighten the feelings of disconnection from the surroundings.

Living in a different environment can have a negative, usually short-term, effect on our health. While negotiating culture shock we may have insomnia because of circadian rhythm disruption, problems with digestion because of gut flora due to different bacteria levels and concentrations in food and water, and difficulty accessing healthcare or treatment (e.g., medicines with different names or active ingredients).

During the negotiation phase, people adjusting to a new culture often feel lonely and homesick because they are not yet used to the new environment and encounter unfamiliar people, customs, and norms daily. The language barrier may become a major obstacle in creating new relationships. Some individuals find that they must pay special attention to culturally specific body language (e.g., arms crossed, smiling), conversation tone, and linguistic nuances and customs (e.g.handshake, turn taking, ending a conversation). International students often feel anxious and feel more pressure while adjusting to new cultures because there is special emphasis on their reading and writing skills.

Adjustment

As more time passes (usually 6 to 12 months), individuals generally grow accustomed to the new culture and develop routines. The host country no longer feels new, and life becomes “normal.” Problem-solving skills for dealing with the culture have developed, and most individuals accept the new culture with a positive attitude. The culture begins to make sense, and negative reactions and responses to the culture have decreased.

Adaption

In the adaptation stage, individuals participate fully and comfortably in the host culture, but this does not mean total conversion or assimilation. People often keep many traits from their native cultures, such as accents, language, and values. This stage is often referred to as the bicultural stage.

Case Study: Voting

Minnesota Joins the National Conversation in 2020 – “Across America: Being Somali- American”

Here is a shorter version of the video above. Nadia mentions that she did not know she was black until she came to America.

Visit the podcast as it aired on National Public Radio: https://the1a.org/segments/2019-09-05-across-america-somali-americans-get-their-say/.

Current Events: SuperModel Halima Aden

Minnesotan, Halima Aden, shares her departure from high fashion and modeling as a resolution to her tug-of war-between cultures. The Guardian quotes Aden, saying, “When I started, I thought: ‘This is going to open the door for so many girls in my community,'” she s ys. “I never got to flip through a magazine and see someone in a hijab, so to be that person for other girls was a dream come t ue. But the last two years [of my career], I had so much internal conflict.”

UNICEF (n.d.) shared the following information from Ms. Aden’s Ambassador bio:

Somali-American supermodel and activist Halima Aden was a UNICEF Ambassador from July of 2018 to December of 2020.

Halima is no stranger to firsts – she was the first Muslim homecoming queen at her high school, the first woman to wear a hijab at a Miss USA state pageant and was the first model to wear her hijab on the covers of major women’s magazine, Allure, British Vogue and Teen Vogue to name a few.

Halima was born in Kakuma, a refugee camp in Kenya, after her family fled civil war in Somalia. She lived there for seven years with her parents before moving to the United States. Early on she developed a passion for empowering young people and a desire to give back, which led to her introduction to UNICEF USA.

As a UNICEF Ambassador, Halima used her voice to engage young people across the U.S. to support UNICEF’s mission to put children first. She brought awareness to programs that save and protect children’s lives and used her platforms to advocate for children’s rights. As a refugee herself, she uniquely understands the needs, along with the hopes and dreams, of the 30 million children around the world who have been forcibly displaced by conflict.

Wikipedia notes:

Halima Aden (born September 19, 1997) is a Somali-American fashion model. She is noted for being the first woman to wear a hijab in the Miss Minnesota USA pageant, where she was a semi-finalist.[2][3] Following her participation in the pageant, Halima received national attention and was signed to IMG Models.[4] She was also the first model to wear a hijab and burkini in the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue.[5]In 2021 she was named as one of the BBC’s 100 Women.[6]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zK4joMN7nEs

Additional Links to Explore

More Oral Stories

- Becoming Minnesotan: Stories of Recent Immigrants and Refugees

- Confederation of Somali Community of Minnesota http://csc-mn.org/

- “Immigrant Stories.” Immigration History Research Center, University of Minnesota, 2 15. https://cla.umn.edu/ihrc/immigrant-stories

- “Minnesota 2.0: Digital Archive.” Immigration History Research Center, University of Minnesota, 2 10. https://sites.google.com/a/umn.edu/mn20/

- Somalis in Minnesota Oral History Project, 2013–2016 Oral History Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/oh176.xml

- Description: Fifty-eight interviews were conducted with Somali residents of the Twin Cities and surrounding areas, as well as the St. Cloud, Rochester, Mankato, and the Fargo-Moorhead area. Interviewees are community leaders, politicians, healthcare professionals, activists, educators, scholars, businesspeople, artists, and poets.

- “Sheeko: Somali Youth Oral Histories.” Immigration History Research Center, University of Minnesota, 2011. http://blog.lib.umn.edu/ihrc/sheeko/

Somali Organizations

- Somali Museum in the Twin Cities

- Somali Family Services http://ussfs.org/

Demographics & Economics

- Check out the changing demographics of Minnesota with the Minnesota State Demographic Center.

- In addition to Somalia, Minnesota is home to immigrants from Mexico, Laos, India, and Cambodia, among others. Explore the demographic profile of MN – our characteristics and languages.

- MN Compass shares a detailed demographic profile of Minnesota’s Somali Community.

- Rochester, ICC INDEX ANALYSIS 2020 – MN’s Intercultural Community Profile

- This report is an in-depth analysis of the community’s intercultural prof le. Rochester will be one of the first cities in the “Intercultural City” distinction.

- Minnesota’s Chamber of Commerce’s “Contributions over Time” Report

- Coming to MineSota Learn about historical migration to Minnesota, from Indigenous origin stories to current events. See this full PBS Documentary to learn more about the complex history.

Works Cited

Bolter, J. (2019, June 0). Explainer: Who is an immigrant? Immigration policy.org. Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/content/explainer-who-immigrant

Connor, P., & Krogstad, J. M. (2020, May 1). 5 facts about the Global Somali diaspora. Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/06/01/5-facts-about-the-global-somali-diaspora/

Contributions change over time. Minnesota Chamber of Commerce. (2021, March 3). Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.mnchamber.com/blog/contributions-change-over-time.

Definition of terms. Definition of Terms | Homeland Security. (n. .). Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/data-standards-and-definitions/definition-terms

Department of Homeland Security. (n. .). Definition of terms. Definition of Terms | Homeland Security. Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/data-standards-and-definitions/definition-terms

Differencebetween.com. (2016, February 4). Difference between diaspora and migration. Compare the Difference Between Similar Terms. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.differencebetween.com/difference-between-diaspora-and-vs-migration/.

Editorial Board. (20 3). The World Bank Research Observer, 28(2), 60. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lks019

Ethnocentrism and Stereotypes. (2020, August 3). Butte College. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/@go/page/47459

Evason, N. (2019). Somali culture. Cultural At as. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/somali-culture/somali-culture-core-concepts#somali-culture-core-concepts.

Feshir, R. (2019, December 3). Willmar keeps the refugee door open despite concerns. Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://www.mprnews.org/story/2019/12/23/willmar-keeps-the-refugee-door-open-despite-concerns

Gerber, P. J., & Murphy, H. (2020, May 8). ICAT interpersonal communication abridged textbook. Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://mytext.cnm.edu/course/i-c-a-t-interpersonal-communication-abridged-textbook/

Guardian News and Me ia. (2021, July 1). ‘Fashion can be very exploitative’ – Halima Aden on why she quit modeling. The Guardian. Retrieved November 28, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2021/jul/22/fashion-can-be-very-exploitative-halima-aden-on-why-she-quit-modelling.

History.com Edit rs. (2018, January 5). Islam. History.com. Retrieved May 1, 2022, from http://www.history.com/topics/religion/islam

Immigration Pol cy. (2021, February 0). https://socialsci.libretexts.org/@go/page/22047