29 Cultural Highlight Section 3 – Explore Native American Cultures

Learning Outcomes

Learning Outcomes

After reading and considering this unit, students will:

- Learn basic facts about Indigenous cultures, primarily those living in and with cultural and social ties to Minnesota

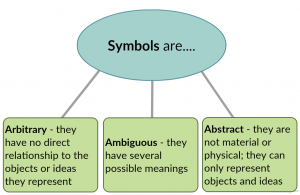

- Understand the power and nature of language, i.e., ambiguous, abstract, and arbitrary

- Define and distinguish between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation

- Understand and practice paraphrasing and perception checks

Cultural Highlight: Native American Cultures

Introduction

This unit will help gain a better understanding and appreciation of the variety of cultures termed “Indigenous,” “Native American,” “Native,” “American Indian,” and “Indian.” This unit includes issues of language use, Minnesota historical events, current events, suggested cultural and historical site visits, and many relevant resource links. The chapter will touch upon contemporary issues such as recognizing “land acknowledgments” before meetings or speakers, conversations surrounding college and pro sports mascots, tragic revelations about boarding/residential schools, the issue of possible reparations for Indigenous peoples, and notions of cultural appreciation and appropriation.

Throughout, one must keep in mind that a monolithic Native American culture does not, nor has ever, existed. Instead, as Dr. Anton Treuer explains in his video below, we need to consider the variety of Indigenous cultures in the United States, no matter the issue or question.

We hope this unit will help answer present questions and lead to new questions to pursue. Our goal as co-authors of this OER textbook is to challenge students to build cultural curiosity and intercultural communication competency. In this chapter, Laura Oakgrove and Gazelle Oakgrove are also co-authors.

If anyone has ideas for additional resources, peer speakers, or site visits, please email lori.halverson-wente@rctc.edu or mhalversonwente@gmail.com.

Meet Peer Speakers, Laura and Gazelle Oakgrove

Laura Oakgrove

Laura Oakgrove has reviewed this chapter’s materials and helped decide what content to include. Since completing the course, she has served as a teaching assistant and volunteer in RCTC’s Intercultural Communication class. Now, Laura’s entire family volunteers, and her daughter also shares her own story below.

Jazelle Oakgrove

Meet Jazelle Oakgrove. She shares her joys and passions and relates experiences as a target of bullying and verbal abuse, e.g., being called a “savage.” Jazelle explains that the word “savage” is as offensive and demeaning to her culture as the “N-word” is to African-Americans.

After watching Jazelle explain her pain of being called “savage,” how did you process this? Perhaps some might think she is too sensitive as this term creates a connotation of someone who, according to the urban dictionary, is “bad-ass,” a term used in song lyrics such as Megan Thee Stallion’s song, “Savage.” It is also the name of a town in Minnesota. It might explain how one feels after working out. It is even a logo on a Target t-shirt. At the same time, “savage” is a heart-wrenching racial slur thrown at a 15-year-old whose culture regards it as deeply offensive.

When reading this unit and watching the videos, consider how the term “savage” powerfully impacts one’s cultural self-concept and self-image. Blogger Chrissy King shares her experience with the same word. She wrote to Target asking them to discontinue selling and investing in a T-shirt with this term. She concludes: “What I realized from the overwhelming amount of responses I received, is that many people have never taken the time to realize how much some words matter. They matter a lot. When people disregard the historical and complicated origins of words in favor of using a word as slang…[In so doing,] we disregard the feelings of people who suffered hundreds of years of oppression and continue to be oppressed today…Ultimately, we people [as the dominant culture] don’t have the right to decide if a word is offensive to a member of a marginalized group” (King, 2021).

Language is ambiguous in its origins, e.g., the dominant culture has forgotten that “savage” or “redskin” were terms of hate and scorn towards native nations and peoples thought inferior. Over time, such words used by the dominant culture became more ambiguous in meaning and taken for granted in their use. Thus, we blind ourselves to the significance of our words and their consequences. Understanding Native American cultures will deepen as more complex perceptions are formed.

Activity – Perception Check

- Listen to Jazelle’s story in the video above.

- At 11:20, Jazelle talks about taking great pride in her culture. She gave a presentation on her culture in which she shared, “saying ‘savage’ to a Native person is like saying the ‘N-word’ to an African American person.”

- Imagine yourself as a teacher at Jazelle’s school when completing these questions:

- List five factual statements from Jazelle’s story.

- List three corresponding inferences drawn from each factual statement to consider how many perceptions you might create.

- Using the three-part perception check, write the perception check you might make as you check in with her. Review the Perception Chapter for more information on perception.

- I noticed that ___________________________ (state observations).

- I am wondering if _______________________ (possible interpretation 1) or perhaps ______________________________ might be the case (possible interpretation 2).

- Can you tell me more (ask for clarification)?

- Go the extra mile: read Stop Saying Savage. What advice does Ms. King offer about language? Do you agree or disagree? What questions would you ask if you could talk to her? Better still, try contacting her and ask her.

Cultural Basics

Why we Need to Learn More

What did you learn in your K-12 schooling about Native American cultures? In an article by Anna Diamond in the Smithsonian (2019), she remarks that she remembers but the “barest minimum” from her social studies courses, such as “re-enacting the first Thanksgiving, building a California Spanish mission out of sugar cubes. or memorizing flashcards about the Trail of Tears.” Diamond continues:

“Most students across the United States don’t get comprehensive, thoughtful or even accurate education in Native American history and culture. A 2015 study by researchers at Pennsylvania State University found that 87 percent of content taught about Native Americans includes only pre-1900 context. And 27 states did not name an individual Native American in their history standards. ‘When one looks at the larger picture painted by the quantitative data,’ the study’s authors write, ‘it is easy to argue that the narrative of U.S. history is painfully one sided in its telling of the American narrative, especially with regard to Indigenous Peoples’ experiences” (Diamond, 2019).

To meet the need of integrating sounder, more profound studies of Native Americans into our school curricula, the Smithsonian offers online lesson plans to help students and teachers. While we designed our OER book for college students, we urge all to try out the curricular materials. Did you know this information? Can you share this with an educator or youth? Do you have your own younger folks to share this with – children, siblings, your friend’s/family’s children? Check out Diamond’s article to learn more.

Activity: Learning with the Smithsonian

- First, write down ten memories you have from your K-12 education concerning any topic about Native American history or contemporary issues.

- Second, if you have a young person in your life, ask them to do the same (or tell you, and you can write it down).

- Now compare notes. If you do not have a young person, Lori can find you one, or you could ask a peer to help. If not, move on to the next question.

- Visit the Smithsonian’s Lesson Plans and complete the lessons, if able, with the young person.

- What did you learn? What didn’t you know before? What else would you like to see in lessons for young people?

- What lessons would you like to learn in an Intercultural Communication class? Laura Oakgrove has volunteered to chat with folks who would like to interview someone from a Native American background.

Basic Overview:

Naming & Intercultural Communication Significance

Throughout the textbook, we have discussed the term “identity.” To review, Communication in the Real World explains, “Personal identities include the components of self that are primarily intrapersonal and connected to our life experiences…Our social identities are the components of self that are derived from involvement in social groups with which we are interpersonally committed…Cultural identities are based on socially constructed categories that teach us a way of being and include expectations for social behavior or ways of acting (Yep, G. A., 2002).”

In many cultures, knowing and publicly pronouncing one’s name (the symbolic representation of one’s cultural and personal identity) is essential. Through language and communication, naming, at root, shapes who one understands themselves to be, hence helping to create/construct both the individual self and one’s group or cultural identity. Language itself “…is intrinsically related to culture [and] performs the social function of communication of the group’s [culture’s] values, beliefs, and customs and fosters group identity” (Bakhtin, 1981). In other words, language is the medium through which groups or cultures preserve their firmly held beliefs and keep their traditions alive in the hearts and minds of their members. Language and names are vital.

Regarding names, perhaps a short nickname can help others when a name is hard to pronounce and can help one remember a person. Still, if the nickname is not preferred or given with love, its sound to its’ possessor can be as annoying as hearing nails scraping across a chalkboard.

Being called “Jimmy” by one’s grandmother when friends and work associates call him “James” could be endearing but most likely embarrassing if James is called Jimmy at work. Having one’s mother come to her son’s place of work asking loudly, “Is my Baby J in the office?” might be another example. The point is that names are personal and defining. They are also verbal symbols. Symbols stand for something else and allow us to communicate due to the meaning attached to the symbol. All symbolic use is dynamic, meaning fluid, and often powerful. Think about when a bully purposefully calls someone a name. Calling another “fattie” or “blubber butt” takes a toll on the bully’s victim. Whether renaming is out of spite, like the bully example, or perhaps misplaced affection, like being called Baby J, if it is not one’s desired name, one might feel that one is not being “acknowledged” or “affirmed,”–a feeling of disconfirmation arises. This feeling can impact the relationship itself.

Interpersonal Communication examines how communication creates confirming or disconfirming communication climates. We experience “Confirming Climates when we receive messages that demonstrate our value and worth from those with whom we have a relationship,” [and], “[c]onversely, we experience Disconfirming Climates when we receive messages that suggest we are devalued and unimportant” (Rice, 2019, pp. 124-125). Disconfirmation leads to feeling objectified or regarded as the “other,” apart from and foreign to one’s own culture and personal experience. Therefore, calling someone as they would like helps create a supportive climate where respectful and impactful intercultural communication can occur. If we generalize and move toward this same treatment to a culture, that too might help create more a supportive environment for intercultural communication.

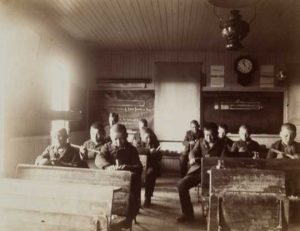

If we see a person or group of people as the Other–apart from us and unknown to us–it may lead to dehumanization. Dehumanization includes “The denial of full humanness to others, and the cruelty and suffering that accompany it” (Haslam, 2006). An example of dehumanization (also highlighted below in the topics section) is the not-so-distant practice of sending Native American children to boarding schools. In the Indian Civilization Act Fund of March 3, 1819, and the Peace Policy of 1869, the United States (along with many Christian churches) allowed for the removal of Native American children from their homes and families so they could be appropriately educated and stripped of their own culture in boarding (or residential) schools (“U.S. Indian boarding school history,” n.d.). “Between 1869 and the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Native American children were removed from their homes and families and placed in boarding schools operated by the federal government and participating churches. It is unknown exactly how many children in total lived in such schools, but by 1900 there were 20,000 children in Indian boarding schools, and by 1925 that number had more than tripled” (“U.S. Indian boarding school history,” n.d.).

An example of taking away a Native American child’s culturally given name and then stating that their new name is, say, “Sarah,” demonstrates the erosion of self (both individual and cultural identity) that many Native American Boarding Schools inflicted upon Native Americans. To clarify, Becky Little (2017), in her article for History.com, reminds us of the phrase, “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” (later shortened to “Kill the Indian, save the man”). This phrase, attributed to Captain Richard Henry Pratt from a speech in 1892 during the National Conference of Charities and Correction, was, in fact, a rejoinder to the widely-endorsed phrase, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” Pratt argued that we must move beyond that thinking to adopt a progressive assimilationist program for Indians to educate them as productive members of mainstream society. Boarding schools, such as the Carlisle Indian School (founded in 1879), attempted to fill “young Indians with the spirit of loyalty to the stars and stripes, and then move them out into our [white] communities to show by their conduct and ability that the Indian is no different from the white or the colored, that he has the inalienable right to liberty and opportunity that the white and the negro have.” The residential/boarding schools, then, were to “civilize” and “Americanize” Native Americans and “free” them of their “backward” culture so that they may flourish and no longer be a problem to the dominant white culture and its interests. (Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, n.d.).

Becky Little (2017) remarked that this federal effort toward assimilation mandated that “… boarding schools forbid Native American children from using their languages and names, as well as from practicing their religion and culture. They were given new Anglo-American names, clothes, and haircuts and told they must abandon their way of life because it was inferior to white people’s.” Though the schools “….left a devastating legacy, they failed to eradicate Native American cultures as they’d hoped.” Later, the Navajo Code Talkers who helped the U.S. win World War II would reflect on this forced assimilation’s strange irony in their lives (2017).

Video Illustration – Reclaiming Native Arts

In the video interview above, Minnesota Historical Society Native American Artist-in-Residence, Mat Pendleton, a member of the Lower Sioux Indian Community of the Mdewakanton Dakota (Cansa’yapi), stresses that one might be faced with resistance if one out-of-the-blue, asks someone from a Native American background to share about their culture. Still, he states, “Ask. There are resources out there. You are going to come across people who will not share because of what happened in the past; it’s not too long ago that our people could not practice our ways.” Matt intentionally shares his knowledge and artistic talent with others to be, as he puts it, a “better ancestor today.”

Similarly, when learning about naming, one might encounter Native American scholars and individuals who believe that one should not share one’s “spirit name” due to spiritual boundaries. It is a great honor when a person shares their name. Native American names are given with great care. As noted by Dr. Elisabeth Pearson Waugaman, Ph.D. (2015)

Native Americans have a fluid naming tradition—i.e., they can earn new names. A Native American wise woman explained this concept to me with nature imagery. Some people are like lakes; they change very little during their lifetimes. Others are like rivers that may change dramatically from their small beginnings to become mighty rivers that travel all the way to the sea. Native American children are given names that suit their personalities. If a name is given and proves to be a bad fit, the child’s name is changed. At adolescence, the given name may be changed again. As the adult progresses through life, new names can be awarded. Family and society award the new names, which provide the individual with a strong social bond to community as well as family. This naming tradition helps to motivate the individual to grow throughout life.

A Native American name can reflect personality, accomplishments, or particular life experiences. The name Dancing Wind sounds beautiful to our ears, but Native Americans know that the dancing wind is a tornado. This name warns of a volatile, angry disposition. It serves as a warning to others and an incentive to Dancing Wind to earn a new name. The name Bear is a common name like John. If the name changes to Wounded Bear, society knows the individual suffers and needs special care. If an individual accomplishes great things, a new name like “Eagle Eye” may be given to recognize the individual’s clear-sighted perception and a special connection between heaven and earth, i.e., with the spiritual world. The Native American naming tradition inspires individuals to strive to be better, heal others, and evolve. The bond between society and the individual is very personal.

Psychologist William Schutz argues that humans have an interpersonal imperative, including the basic needs of affection (desire to give & receive love & liking), inclusion (desire to be social & to be included), and control (desire to influence people & events). The dominant white interpersonal imperativeculture took Native Americans’ control over their names and separated them from sacred lands and traditions. Indeed, Communication in the Real World (University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, 2016) highlights Yancy’s assertion that “members of the dominant group are more likely to assert and tend to define what is correct or incorrect usage of language, and since language is so closely tied to identity, labeling a group’s use of a language as incorrect or deviant challenges or negates part of their identity.” Stopping to listen, learn, and use the language requested by a culture repositions this sense of control and allows for a better empowering balance.

Individuals from all cultures desire to have their names correctly stated. Therefore, one of the first ways to become more interculturally competent is to learn one’s correct pronunciation of their preferred name and pronouns. American-given names or English names were not endearing nicknames in the past. Additionally, the person’s name is not hard to pronounce if one is from that person’s culture. We recommend just learning the correct pronunciation. Often, individuals need to “code-switch” their names. Adopting the name “Jenny” at school because your given name is “too hard to say” requires that students switch between 2 different “codes.” The OER text Communication in the Real World shares Yancy’s 2011 work on code-switching:

Code-switching involves changing from one way of speaking to another between or within interactions. Some people of color may engage in code-switching when communicating with dominant group members because they fear they will be negatively judged. Adopting the language practices of the dominant group may minimize perceived differences. This code-switching creates a linguistic dual consciousness in which people are able to maintain their linguistic identities with their in-group peers but can still acquire tools and gain access needed to function in dominant society (2016).

The significance of naming in Native American cultures expands beyond a person’s name(s). In addition to the importance of one’s name being correctly stated, one’s group identity’s name is also significant as a nation or tribe. In Native American culture, names, whether they are naming an area of land or conducting a naming ceremony, is so important.

Revitalization: Currently, many scholars are seeing a revitalization of Native American culture (including language use) in the younger generations seeking to learn about their particular cultural traditions. Time is of the essence. Elders with knowledge of time-honored sacred ceremonies and unwritten language who were punished, degraded, and dehumanized for practicing their culture might not have previously shared (or just not known) information with their children and subsequent generations. As one reads and hears more about land acknowledgments, efforts to discover unmarked graves of boarding school children, campaigns to change dehumanizing mascots, and requests to address appropriation of culture through actions such as stopping “playing Indian” and not treating my culture as a costume, we hope you will recall the points made in this section and seek out more information as you consider your response.

Continue the Learning:

More Information on Native American Naming:

Should I use my Indigenous name in public? In the video above, “Dr. Anton Treuer shares a perspective about the use of Indigenous names in public speaking, social media, and print publications. There is the historical context and an examination in the competing needs of privacy and decolonization and Indigenous empowerment” (YouTube Description).

More information on Naming & Identity Development:

- The Multifaceted Native American Naming

- Stereotyping Native Americans

- Communication in the Real World’s chapter explains how ascribed and avowed personal, social, and cultural identities are created.

- Survey of Communication Study/Chapter 12 on Intercultural Communication Study/Chapter_12_-_Intercultural_Communication

What term is most appropriate for teaching about Native Americans?

In his teaching resource, Why Treaties Matter: Terminology Primer (n.d.), Dr. Anton Treuer addresses the confusion surrounding which term to use — “Native American,” “Native,” “Indigenous,” or “American Indian.” There is no correct answer or term to use, as seen below. Confusion arises due to the notion of language ambiguity. Ambiguity refers to the idea that symbols have several different meanings. The reverse is true too. We have many different symbols to refer to the same referent; e.g., soda, pop, soda pop, and coke can all refer to the same beverage one might be drinking, even if it is “7-up!” The beverage itself is the “referent” or thing being referred to; the symbol is the word used to refer to it. Recall that the nature of language is ambiguous, arbitrary, and abstract, which is discussed in the chapter on verbal communication. It is not surprising that the language used to name such a large group of individuals from 574 different nations registered in the United States would be hard to determine. Dr. Treuer (n.d.) explains:

This is an area of confusion for many people. Christopher Columbus thought for a long time that he landed in Asia when he first arrived here—China, Japan, India. And from there the term Indian was applied to the peoples of the Americas. It is a misnomer, even if it wasn’t intended to offend. Some native people object to the word because it was applied in error. But some really do prefer the term, including some official organizations like the National Congress of American Indians and the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council. Native American is broadly considered a little more politically correct, even if it isn’t universally embraced. But it can cause confusion in certain circumstances. Is a St. Paul native a Native American from St. Paul or just someone “born and bred,” so to speak? Indigenous is increasingly taking the place of Native American, and some scholars really like the way it draws connections to other groups, but again there is an issue of ambiguity. There are people indigenous to every continent except Antarctica and they are all different. It gets a little long to always say “indigenous people of North America.” Aboriginal was preferred for a while in Canada, although it got confused with Australian aborigine. I tend to use all of these terms fairly interchangeably, aware of their shortcomings… If you know the story behind the words, all you really need is respect in your heart and an open mind (p. 1).

Suggestions on how to use language respectfully are highlighted in the shared curricular materials from the “Quick Links” resource from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (n.d.):

- “American Indian, Indian, Native American, or Native are acceptable and often used interchangeably in the United States; however, Native Peoples often have individual preferences on how they would like to be addressed. To find out which term is best, ask the person or group which term they prefer.”

- “When talking about Native groups or people, use the terminology the members of the community use to describe themselves collectively.”

- “There are also several terms used to refer to Native Peoples in other regions of the Western Hemisphere. The Inuit, Yup’ik, and Aleut Peoples in the Arctic see themselves as culturally separate from Indians. In Canada, people refer to themselves as First Nations, First Peoples, or Aboriginal. In Mexico, Central America, and South America, the direct translation for Indian can have negative connotations. As a result, they prefer the Spanish word indígena (Indigenous), communidad (community), and pueblo (people).”

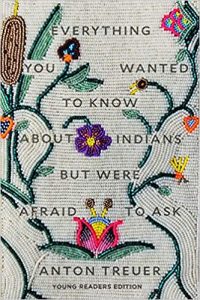

In his book, Everything you Wanted to Know about Indians but were Afraid to Ask (2014), Dr. Treuer shares that “…each tribe has its own terms of self-reference” (p. 9). Truer continues, stressing that “…one should not use words, including “squaw,” “brave,” and “papoose.” He explains that some words “..create distance, use hurtful cliches to point out the difference, and say clearly that ‘those people are not like normal people’ (Treuer, 2014, p. 8). Regarding terminology, Smithsonian’s Native Knowledge 360* posits that one should “[r]efrain from using terminology and phrases that perpetuate stereotypes…. Phrases like ‘Indian Princess,’ ‘Low man on the totem pole,’ ‘sitting Indian style,’ etc., perpetuate stereotypes and imply a monolithic culture.” Native people are also treated as objects in counting songs, books, and toys” (Hirschfelder and Molin, 2018). Singing a song such as “Ten Little Injuns” perpetuates stereotypes and reckons back to genocide (it has also been adapted into a racist image of 10 Little N___r’s). “If you are unsure about a phrase, do some research into its origins and think about its meaning and implications” (National Museum of the American Indian: Smithsonian, n.d.). As with other cultures and co-cultures, avoid generalizations and use context, dates, and more factual information. When looking for non-offensive terms, refer to the chapter on language. Note that stigmatizing language is often determined by that dominant culture–group(s) in positions of power and privilege–Americans of European ancestry–who use language to define and diminish others to further their interests. Remember, too, that social capital can equal privilege. Systematic policy, language structure, and biased attitudes also create damaging language.

In his book, Everything you Wanted to Know about Indians but were Afraid to Ask (2014), Dr. Treuer shares that “…each tribe has its own terms of self-reference” (p. 9). Truer continues, stressing that “…one should not use words, including “squaw,” “brave,” and “papoose.” He explains that some words “..create distance, use hurtful cliches to point out the difference, and say clearly that ‘those people are not like normal people’ (Treuer, 2014, p. 8). Regarding terminology, Smithsonian’s Native Knowledge 360* posits that one should “[r]efrain from using terminology and phrases that perpetuate stereotypes…. Phrases like ‘Indian Princess,’ ‘Low man on the totem pole,’ ‘sitting Indian style,’ etc., perpetuate stereotypes and imply a monolithic culture.” Native people are also treated as objects in counting songs, books, and toys” (Hirschfelder and Molin, 2018). Singing a song such as “Ten Little Injuns” perpetuates stereotypes and reckons back to genocide (it has also been adapted into a racist image of 10 Little N___r’s). “If you are unsure about a phrase, do some research into its origins and think about its meaning and implications” (National Museum of the American Indian: Smithsonian, n.d.). As with other cultures and co-cultures, avoid generalizations and use context, dates, and more factual information. When looking for non-offensive terms, refer to the chapter on language. Note that stigmatizing language is often determined by that dominant culture–group(s) in positions of power and privilege–Americans of European ancestry–who use language to define and diminish others to further their interests. Remember, too, that social capital can equal privilege. Systematic policy, language structure, and biased attitudes also create damaging language.

Activity: Read the National Association of Journalists Association’s (NAJA) expl

anation about the terms used for “Indian Country” and “Tribal Affiliation” here: Reporting and Indigenous Terminology Guide.

Note that the NAJA also presents their suggestions for incorrect and correct recommended language use when discussing places and people.

- Compare and contrast the NAJA example – list three observations you can make about their incorrect and correct examples.

- Create your own “correct” examples by filling in the blank:

- Example 1

- Statement: Governor expands message to Minnesota SE City

- Your Edited Version:____________________________________.

- Example 2

- Statement: Foriegn nation seeks tariff reform with the United States.

- Your Edited Version: ____________________________________.

- Example 3:

- Indiginous Nation promotes Minnesota wild rice consumption.

- Your Edited Version: ____________________________________.

- Example 1

- Explain how this lesson illustrates the difference between abstract and concrete language.

Photo from: NAJA. (n.d.). Native American Journalists Association –Reporting and Indigenous Terminology. najanewsroom.com. Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://najanewsroom.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/NAJA_Reporting_and_Indigenous_Terminology_Guide.pdf

Dispelling Cultural Myths with Dr. Anton Treuer

Dr. Anton Treuer is a professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University. The following video was recorded during COVID 19. He addresses a question Lori typed in the video, “What is the difference between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation?” Lori also had asked what term one should use: Native, Native American, American Indian, Indigenous, or Indian. Watch this video for an excellent overview of the concerns Native American cultures are facing.

“Hear award-winning Ojibwe author and professor Dr. Anton Treuer discuss his latest book Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid To Ask: Young Readers Edition. Dr. Treuer will address cultural myths and answer questions raised by Native and non-Native youth. Registration required. Geared for adults and youth ages 12 and older. A Minnesota Legacy program” (YouTube Description).

Frequently Asked Questions

Asking and addressing questions helps build cultural competency

Asking questions and learning the answers about a new culture or co-culture and one’s own culture can help build cultural competency. “Cultural competency can be defined as the ability to recognize and adapt to cultural differences and similarities. It involves “(a) the cultivation of deep cultural self-awareness and understanding (i.e., how one’s own beliefs, values, perceptions, interpretations, judgments, and behaviors are influenced by one’s cultural community or communities) and (b) increased cultural other-understanding (i.e., comprehension of the different ways people from other cultural groups make sense of and respond to the presence of cultural differences). In other words, cultural competency requires you to be aware of your own cultural practices, values, and experiences, and to be able to read, interpret, and respond to those of others. Such awareness will help you successfully navigate the cultural differences you will encounter in diverse environments. Cultural competency is critical to working and building relationships with people from different cultures; it is so critical, in fact, that it is now one of the most highly desired skills in the modern workforce” (“Diversity and Cultural Competency | OER Commons,” n.d.).

This section provides information from various sources noted in the answers to help you gain more knowledge to place in your cultural competency toolbox. Please email lori.halverson-wente@rctc.edu or mhalversonwente@gmail.com with additional questions or information you would suggest.

Question: To What does “Native” Refer?

Answer: According to the National Museum of the American Indian: Smithsonian (n.d.), the term “Native” is “often used officially or unofficially to describe indigenous peoples from the United States (Native Americans, Native Hawaiians, Alaska Natives), but it can also serve as a specific descriptor (Native people, Native lands, Native traditions, etc.).”

Question: Should I say Tribe or Nation, and Why So Many Names?

Answer:

American Indian people describe their own cultures and the places they come from in many ways. The word tribe and nation are used interchangeably but hold very different meanings for many Native people. Tribes often have more than one name because when Europeans arrived in the Americas, they used inaccurate pronunciations of the tribal names or renamed the tribes with European names. Many tribal groups are known officially by names that include nation. Every community has a distinct perspective on how they describe themselves. Not all individuals from one community many agree on terminology. There is no single American Indian culture or language…The best term is what an individual person or tribal community uses to describe themselves. Replicate the terminology they use or ask what terms they prefer” (National Museum of the American Indian: Smithsonian, n.d.)

Question: Should I say Ojibwe or Chippewa?

Answer: Dr. Trauer (n.d.) shares,

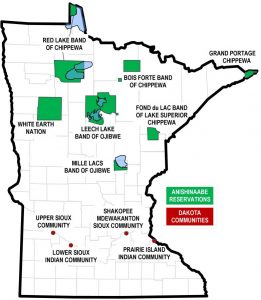

It is Ojibwe. The word Chippewa is actually derived from the word Ojibwe. Always Eakl French explorers and traders had trouble spelling words for which there were no written languages, so many versions and spellings were recorded over time. The word went from Ojibwe to Jibwe, to Chipwe, Chippeway, Chippewa. It’s not hurtful or offensive, just a moderate corruption. That corrupted spelling was formally incorporated into many treaties, U.S. government documents, and the constitutions of all seven Minnesota Ojibwe tribes, so the word Chippewa is far from dead. Ojibwe is winning out, and as the tribes successfully reform their constitutions, Chippewa will likely slowly be on its way out. Many Ojibwe people also use the term Anishinaabe. Ojibwe is considered a tribal-specific term, meaning just a reference to Ojibwe people. “Anishinaabe” is an Ojibwe word that refers to all native people of all tribes (p. 2).

Question: Should I say “Dakota” or “Sioux?”

Answer: Dr. Treuer (n.d.) shares,

It is Dakota, usually. The word Dakota, meaning friend or ally is the term the tribe uses for self reference most commonly. Use of the name Sioux is relegated to the past. The word Sioux is a derivation of the Ojibwe word Naadowesiwag, which is a species of snake, and reference to the Dakota as enemies. That does offend some Dakota people. But the Dakota are part of a much larger linguistic and cultural family. The Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota are all dialects and branches of the same tribal family tree. They formed a political confederacy as well—the Seven Council Fires. Four of those seven groups were Dakota, two were Nakota, and one was Lakota. The Lakota further diversified into other bands. Sometimes, it’s hard to find one word that easily encompasses them all, so you will hear Dakota people sometimes use the word Sioux in self reference, but the tribal-specific words are usually preferred—Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota. The Dakota Nation comprises tribes that share a common language, history, social organization, and culture. Tribes within the Dakota Nation are the Santee Dakota, Yankton Dakota, and Teton Dakota, labels representing three dialectic divisions of the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires): 1. Wahpetonwan – Santee Dialect 2. Mdewakantonwan – Santee Dialect 3. Sisitonwan – Santee Dialect 4. Wahpekute – Santee Dialect 5. Ihanktonwan – Nakota Dialect 6. Ihanktonwana – Nakota Dialect 7. Titonwan – Lakota Dialect (Please note that Lakota is a dialect, not a tribe name) (p. 2).

Question: How could I learn more about the Dakota, Lakota, and Ojibwe Languages?

Answer: There is a Dakota Dictionary Online, Lakota Language Forum Dictionary, and the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary. You could take classes at several Minnesota colleges and universities. Also, most reservations have an education director you can contact for Nation and specific programs.

Question: How many Native Americans live in Minnesota?

Answer: 65,819 according to the 2020 Decennial Census redistricting data. This number is the count of Minnesotans who identified as White and American Indian or Alaska Native and includes individuals of both Hispanic and non-Hispanic origins (P.L. 94-171 Redistricting Data, 2020 Decennial Census). M.N. Compass reports that ff that population, 44.2% reside in the Twin Cities and 55.8% live in Greater Minnesota (“Native American,” 2021).

The 10 Cities In Minnesota With The Largest Native American Population For 2021:

- Bemidji

- Cloquet

- International Falls

- Detroit Lakes

- Virginia

- East Grand Forks

- St. Anthony

- Morris

- Thief River Falls

- Brainerd

For more demographic data, see: https://www.mncompass.org/topics/demographics/cultural-communities/native-american

Question: What is a Land Acknowledgment? Why am I hearing more about this?

Answer: The definition of National Museum of the American Indian and the Smithsonian (2021) follows:

Land acknowledgments are oral or written statements used to recognize Indigenous peoples as the original stewards of the lands on which a person may live, work, or go to school. Land acknowledgment is a traditional custom that dates back centuries for many Native nations and communities. For example, in Coast Salish communities along the Pacific Coast, another tribe or nation would ask permission to come ashore, thus acknowledging they were visitors to the lands. Acknowledging original Indigenous inhabitants today is often complex because of the centuries of displacement experienced by many Native peoples through (broken) treaties, government policy, and relocation efforts. Throughout their histories, Native groups have relocated and successfully adapted to new places and environments. Many Native peoples are active members of city communities today and many cities are built on top of Indigenous villages and towns (National Museum of the American Indian: Smithsonian, n.d.).

Question: What is an Example of a Land Acknowledgment I might Hear?

Answer: One example is from the system office of Minnesota State:

Minnesota State acknowledges the land and the tribal nations upon whose land this work is being accomplished. We acknowledge that we are on Dakota land. We recognize the Native Nations of this region who have called this place home over thousands of years including the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe), Lakota, Nakota, Ho-Chunk, and Cheyenne. We acknowledge the ongoing colonialism and the legacies of violence, displacement, migration, and settlement that foreground the formation of Minnesota State Colleges and Universities and subsequently this report. We commit to advancing critical efforts to understand and address these legacies, including the larger conversation of reparations, repatriation, and redress urgently needed for the scope of ethical acknowledgment to begin in earnest (MN State, 2021).

Question: What are Native American Reservations?

Answer: The National Museum of the American Indian and the Smithsonian (2021) share:

Native American land holdings were greatly reduced by the development and growth of the United States. According to the U.S. Department of the Interior, a Native American reservation is defined as “an area of land reserved for a tribe or tribes under treaty or other agreement with the United States, executive order, or federal statute or administrative action as permanent tribal homelands, and where the federal government holds title to the land in trust on behalf of the tribe.” Some Native nations were able to retain a portion of their original homelands as reservations. Others were able to negotiate for reservation lands in new locations as a result of being forcibly removed from their original lands. Not all federally recognized Native nations have a reservation, but there are other mechanisms by which they can acquire lands. Many Native Americans do not live on tribal lands, choosing instead to live in other urban and rural locations. There are also reservations in some states where the state, not the federal government, holds the lands in trust for the Native nation (National Museum of the American Indian: Smithsonian, n.d.). To learn more about other kinds of Native lands, see this Fact Sheet.

Question: What is a Powwow?

Answer: “The word powwow comes from the Algonquian word pau-wau, which means a curing or healing ceremony. Today the English term is used as a noun to mean any Native gathering or as a verb meaning ‘to confer council.’ To Native people throughout North America, the term refers to important tribal gatherings and celebrations, and it signifies the survival of Native identity and culture. Powwows are social events that are open to all people, Native and non-Native” (National Museum of the American Indian: Smithsonian, n.d.).

Question: When did Institutions Start Using Native Americans as Mascots?

Answer: The Smithsonian shares, “In the early twentieth century, universities and colleges began to take on nicknames. Some adopted names such as ‘Indians’ and ‘Warriors.’ This phenomenon was influenced in large part by society’s understanding of events in United States and Native American history, especially the aftermath of the Battle of Little Big Horn (1876)” (National Museum of the American Indian: Smithsonian, n.d.).

Question: Why is “Playing Indian” seen as Degrading when “Playing Cowboy” is not?

Answer:

Let’s Play Indian, a children’s book by Madye Lee Chastain, is one of countless examples of playing Indian, a practice engaged in by outsiders who appropriate, or take on, American Indian identities and cultural ways. Chastain’s main character transforms herself into ‘a really truly dressed-up painted Indian,’ who runs, whoops, and waves her tomahawk. As columnist Ruth Hopkins notes, ‘Some folks contend that since it’s acceptable to dress up as a cowboy, they should get a pass for dressing up as an ‘Indian.’ Wrong.’ While children frequently dress up to play a cowboy, nurse, or fire fighter, these are occupations. Being American Indian is not a profession or vocation. It is a human identity, tribally specific and integral to Native personhood and nationhood (Hirschfelder and Molin, 2018).

Question: What is Indigenous Peoples’ Day

Answer:

“More and more states are replacing Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day. This effort is in recognition of the devastation that Columbus wreaked on Native communities in the Caribbean and beyond and that Indigenous peoples are survivors and continue to thrive. Contemporary Native Americans have led numerous movements to advocate for their own rights. Native people continue to fight to maintain the integrity and viability of Indigenous societies. American Indian history is one of cultural persistence, creative adaptation, renewal, and resilience. Native peoples, students, and allies are responsible for official celebrations of Indigenous Peoples’ Day in such states as Maine, Oregon, Louisiana, New Mexico, Iowa, as well as Washington, DC. Indigenous Peoples’ Day is celebrated on the second Monday of October and recognizes the resilience and diversity of Indigenous peoples in the United States” (American Indian: Smithsonian, n.d.).

Question: What is the Bureau of Indian Affairs? Arbitrary

Answer:

“The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is the primary federal agency charged with carrying out the United States’ trust responsibility to American Indian and Alaska Native people, maintaining the federal government-to-government relationship with the federally recognized Indian tribes, and promoting and supporting tribal self-determination. The bureau implements federal laws and policies and administers programs established for American Indians and Alaska Natives under the trust responsibility and the government-to-government relationship” (U.S. Department of the Interior: Indian Affairs, n.d.)

Question: How do I Avoid Generalizations?

Answer: The Smithsonian, in their educator resources, suggests that you:

Use conditional language instead! Instead of generalizing phrases like ‘all Native Americans,’ use conditional language such as ‘most Native Americans” or “different Indigenous cultures.’ There is no one ‘Indian’ language, culture, or way of thinking. Generalizations negate the diversity of Native peoples and create an inaccurate understanding for students. Whenever possible, have your students learn about specific individuals from a community (National Museum of the American Indian: Smithsonian, n.d.).

Question: Where can I find More Demographic Information?

Answer: These two websites, in addition to census data, can help. However, remember, that not all surveys include all members of a particular demographic.

- Minnesota Compass – Native American Population

- American Indians in Minnesota “Fact Sheet” from Ucare’s Cultural Care Connection series

- Historic Data – Gale Family Library Census Records: Indian Census

Question: Where can I Listen to More Voices About Relevant Topics?

Answer: http://treatiesmatter.org/exhibit/videos/

Question: Where are the Federally Recognized Minnesota Tribes Located?

Answer: More information about the Minnesota Indian Tribes can be gained from the links below: https://mn.gov/portal/government/tribal/mn-indian-tribes/. There is a State of Minnesota training module at: https://www.dot.state.mn.us/tribaltraining/tribe-map.html.

Minnesota Federally Recognized Indian Tribes

Recognition is a legal term meaning that the United States recognizes a government-to-government relationship with a tribe and that a tribe exists politically in a domestic dependent nation status. A federally recognized tribe is one that was in existence, or evolved as a successor to a tribe at the time of original contact with non-Indians.

Federally recognized tribes possess certain inherent rights of self-government and entitlement to certain federal benefits, services, and protections because of the special trust relationship.

Tribes have the inherent right to operate under their own governmental systems. Many have adopted constitutions, while others operate under Articles of Association or other bodies of law, and some still have traditional systems of government. The chief executive of a tribe is generally called the tribal chairperson, but may also be called the principal chief, governor, or president. The chief executive usually presides over what is typically called the tribal council. The tribal council performs the legislative function for the tribe, although some tribes require a referendum of the membership to enact laws.

Content Source: The Department of the Interior, Office of American Indian Trust

Minnesota Tribes

In Minnesota, there are seven Anishinaabe (Chippewa, Ojibwe) reservations and four Dakota (Sioux) communities. Find links to the websites of those communities that have websites. Also included are links to other valuable resources.

Federally Recognized Indian Tribes

What does the term Federally Recognized mean?Bois Forte Band of Chippewa

The Bois Forte Band of Chippewa is located in northern Minnesota, approximately sixty miles south and west of International Falls, MN.Fond Du Lac Reservation

The Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Reservation lies in Northeastern Minnesota adjacent to the city of Cloquet, MN, approximately 20 miles west of Duluth, MN. The Fond du Lac Reservation, established by the LaPointe Treaty of 1854, is one of six Reservations inhabited by members of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe.Gichi-Onigaming / Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

The Grand Portage Reservation is located in Cook County in the extreme northeast corner of Minnesota, approximately 150 miles from Duluth. It is bordered on the north by Canada, on the south and east by Lake Superior and on the west by Grand Portage State Forest.Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe

The Leech Lake Reservation, located in the forests of north-central Minnesota, offers an oasis of natural beauty. Towering pines fringe the reservations many lakes, two of which are among the largest in the state.Lower Sioux Indian Community

The Lower Sioux Indian Community is located on the south side of the Minnesota River at the site of the U.S. Indian Agency and the Bishop Whipple Mission, a part of the original reservation established in the 1851 Treaty. It is in Redwood County, two miles south of Morton and six miles east of Redwood Falls.Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe

History, tribal government, educational material, links to casinos and museum.Prairie Island Indian Community

Prairie Island Indian Community is located in southeastern Minnesota, north of Red Wing, between Highway 61 and the Mississippi River. The people of Prairie Island are Mdewakanton Dakota and have lived on Prairie Island for countless generations.Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians

Historical information, tribal planning, employment and training, Pow-wow pages, gaming, telephone directory and more.Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux (Dakota) Community

The Shakopee-Mdewakanton Reservation is located entirely within the city limits of Prior Lake, in Scott County, Minnesota. The reservation was known as the Prior Lake Reservation until its reorganization under the Indian Reorganization Act on November 28, 1969. The tribal headquarters is in Prior Lake, Minnesota.Upper Sioux Community

The land called Pejuhutazzi Kapi (the place where they dig for yellow medicine) has been the homeland of the Dakota Oyate (Nation), for thousands of years. The Upper Sioux Community is located in Yellow Medicine County.White Earth Reservation

The White Earth Reservation is located in the northwestern Minnesota counties of Mahnomen, Becker, and Clearwater. The reservation is located 68 miles from Fargo and 225 miles from Minneapolis/St. Paul. Tribal headquarters are in White Earth, MinnesotaAttribution: the materials above are directly quoted from mn.gov/portal/government/tribal/mn-indian-tribes/.

More about Minnesota Nations

Dakota Place Names in Minnesota

“This land called “Mni-sota” is home to the Dakota people. They have been intimately connected to the region within and beyond the boundaries of Minnesota for a very long time. The land, language, and ways of life are all connected for the Dakota people, and they cannot exist without each other. Learn more about Dakota translations of various cities and places around Minnesota, and test your knowledge by taking a quiz! (YouTube Desription, 2020).

- Visit the 2nd part as well.

What we Have Been Gifted

Documentary about the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe – “Entitled ‘What we have been gifted,’ this hour-long documentary was released in 2009 to DVD and focuses on the lives and culture of the people that make up this small Indian Reservation in Minnesota. The LLBO’s capitol city is Cass, Lake, MN. It was produced by Parthé Visual Communications of Duluth, MN” (YouTube Descirption, 2018).

Video Resources & Special Topics

What is a Clan?

Dr. Anton Treuer explains the origin and function of the clan system in Ojibwe culture and how it has changed over time. Narration is in English with some Ojibwe vocabulary.

Greetings in Ojibwe

What is a Land Acknowledgment?

Additional links on Land Acknowledgments

- Dr. Anton Treuer, Professor of Ojibwe at M.N. State, Bemidji, shares his view on Indigenous Land Acknowledgements

- “Anton Treuer shares about Indigenous Land Acknowledgements—what they are, why they are important, what a good land acknowledgment will include and avoid, and how to develop a sound process for developing one for your organization or institution” (Bemidji State University YouTube Channel Description).

- Indigenous Voices – Land Acknowledgment

- This is a short explanation of the relationship between the earth and humans.

- Native Governance Center’s – Beyond Land Acknowledgment -This video asks allies and institutions to do their homework and, if they want to create a land acknowledgment, they do more than just add this statement as, “optical allyship;” they suggest that action steps and true support are needed as well.

- “Have you ever heard a land acknowledgment statement and thought, “What’s next?” Are you looking for ways to take meaningful action to support Indigenous people and nations? The recording from Native Governance Center’s event, “Beyond Land Acknowledgment,” helps viewers understand why it’s important to move beyond land acknowledgment and toward action. We take a close look at three case studies: Indigenous land return, voluntary land taxes, and showing up at Native-led protest movements. Hosted by Nikki Pitre (CNAY Executive Director). Panelists: Michelle Vassel and David Cobb (Wiyot Honor Tax), President Robert Larsen (Lower Sioux Indian Community), and Joye Braun (Indigenous Environmental Network). For more on how to go beyond land acknowledgment, visit nativegov.org” (YouTube Description).

- Samples of Land Acknowledgements

- Video of UMD’s Land Acknowledgement Statement

- (Canada) Questioning the usefulness of land acknowledgments | APTN InFocus

Cultural Appropriation vs. Cultural Appreciation (What is Naive American Cultural Appropriation?)

This video shares a discussion explaining this difference. The speakers share how to appreciate most respectfully. The Tribal Trade Co. shares this definition in the video, “Cultural appropriation is when someone takes elements of a culture that is not their own and reuses it or reduces it into a trend, stereotype or a pop culture item…One of the key ways to know the difference between cultural appropriation and appreciation (Tribal Trade Co., 2020):

“Indigenous people have a rich and vibrant culture that has long been the subject of close inspection and attempts at replication. Knowing the difference between cultural appropriation and cultural appropriation in order to avoid offending native people by doing cultural appropriation. Indigenous cultural appreciation is a lot better than indigenous cultural appropriation. First nations culture is beautiful and it can be tempting to adopt the traditions and practices of its people. Aboriginal indigenous racism or indigenous culture racism has been around for ages and it’s offensive for the indigenous culture and the native Americans and native Canadians. The native culture should not be used for fun but the teachings should be used with respect and with the right intentions and practice culture appreciation” (YouTube Description).

Additional information related to cultural appropriation:

Pow Wows

Mankato, MNThe Annual Traditional Mahkato Wacipi

Experience the annual Wacipi (Pow Wow) in the Land of Memories Park each fall.

Attending a traditional Wacipi, or “Pow Wow,” is one way to gain insight into the rich traditions of various Indigenous co-cultures. The Mission Statement of the sponsoring organization shares the organization’s commitment:

The Mahkato Mdewakanton Association is a gathering of nations to celebrate and honor our traditions and ancestors; to reconcile and build bridges between all nations through education, storytelling, and sharing of Dakota Indian culture (Mahkato Mdewakanton Association, 2021).

Each fall, the celebration is held at the Dakota Wokiksuye Makoce (or Land of Memories Park) in Mankato, Minnesota. For more information, see https://www.mahkatowacipi.org/.

Mankato’s location is an easy drive for many students, and, due to the M.N. State University, Mankato’s American Indian Affairs office, local resources are readily available to learn more (https://mankato.mnsu.edu/university-life/diversity-and-inclusion/multicultural-center/american-indian-affairs/).

“American Indian Affairs provides American Indian students of all tribal backgrounds at Minnesota State University with support services during their college careers.”

Residential Schools

Special Topics Highlighted:

Native American Boarding Schools

Creator: Dr. Denise K. Lajimodiere | shared under a creative commons license from the creator of the story and © Minnesota Historical Society

Native American boarding schools, which operated in Minnesota and across the United States beginning in the late nineteenth century, represent a dark chapter in U.S. history. Also called industrial schools, these institutions prepared boys for manual labor and farming and girls for domestic work. Whether on or off a reservation, the boarding school carried out the government’s mission to restructure Native people’s minds and personalities by severing children’s physical, cultural, and spiritual connections to their tribes.

On March 3, 1891, Congress authorized the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to create legal rules that required Native children to attend boarding schools. It also authorized the Indian Office to withhold rations, clothing and other annuities from Native parents or guardians who would not send and keep their children in school. Indian Agents forcibly abducted children as young as four from their homes and enrolled them in Christian- and government-run boarding schools beginning in the mid-1800s and continuing into the 1970s.

Captain Richard H. Pratt’s boarding school experiment began in the late nineteenth century. A staunch assimilationist, Pratt advocated a position that diverged slightly from the white majority’s. Convinced of the U.S. government’s duty to “Americanize” Native people, he offered a variation of the slogan—famous in the American West— that stated the only good Indian was a dead one. The proper goal, Pratt claimed, was to “kill the Indian…and save the man.”

Pratt founded a school in 1879 at the site of an unused cavalry barracks at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, organizing the institution along rigid military lines. Pratt’s program of half days in the classroom and half days spent in some form of manual labor soon became standard boarding school curriculum. Government expenditures for boarding schools were always small, and the schools exploited the free labor of Native children in order to function.

Minnesota had sixteen boarding schools that drew students from all eleven of the state’s reservations. The earliest was White Earth Indian School, began in 1871. In 1902, St. Mary’s Mission boarded an average of sixty-two students, Red Lake School seventy-seven, and Cross Lake forty-two. More than two thousand children attended the school at Morris during its history. White Earth had room for 110 students. Clontarf housed an average of 130 children from reservations in the Dakota Territory. By 1910, Vermilion Lake held 120 students. Cass/Leech Lake opened with a capacity of fifty students. Pipestone housed children from Dakota, Oneida, Potawatomi (Bodéwadmi), Arikara, and Sac and Fox (Sauk and Meskwaki) tribes.

A typical daily schedule began with an early wake-up call at 5:45 am, most often announced by a bugler or bells. Students marched from one activity to the next. Every minute of the day was scheduled; mornings began with making beds, brushing teeth, breakfast, and industrial call (“detail”). School began around 9 am. Afternoons were spent in school and industrial work, which were followed by supper, up to thirty minutes of recreation, a call to quarters, and “tattoo.” Pupils retired to the sounds of taps at 9 pm.

Methods of discipline at Minnesota boarding schools were harsh. Some schools had cells or dungeons where students were confined for days and given only bread and water. One forced a young boy to dress like a girl for a month as a punishment; another cut a rebellious girl’s hair as short as a boy’s. Minnesota boarding schools recorded epidemics of measles, influenza, blood poisoning, diphtheria, typhoid, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, pneumonia, trachoma, and mumps, which swept through overcrowded dormitories. Students also died from accidents such as drowning and falls.

Boarding school staff assigned students to “details”: working in the kitchen, barns, and gardens; washing dishes, tables, and floors; ironing; sewing; darning; and carpentry. The schools also extensively utilized an “outing” program that retained students for the summer and involuntarily leased them out to white homes as menial laborers.

One of Minnesota’s most famous boarding school survivors is Native American activist Dennis Banks. When he was only four years old, Banks was sent three hundred miles from his home on the Leech Lake Reservation of Ojibwe, in Cass County, to the Pipestone Indian School. Lonesome, he kept running away but was caught and severely beaten each time. Another student, at St. Benedict’s, recalled being punished by being made to chew lye soap and blow bubbles that burned the inside of her mouth. This was a common punishment for students if they spoke their tribal language.

Many students’ parents and relatives resisted the boarding school system. In letters sent to absent children, they delivered news from home and tried to maintain family ties. In messages sent to school administrators, they arranged visits, advocated for improved living conditions, and reported cases of malnourishment and illness.

In 1928, the U.S. government released the Meriam Report, an evaluation of conditions on Native American reservations and in boarding schools. The critical study called the schools grossly inadequate. It presented evidence of malnourishment, overcrowding, insufficient medical services, a reliance on student labor, and low standards for teachers. As a result, the government built day schools on reservations. The original boarding schools began closing their doors as parents increasingly kept their children at home. By the end of the 1970s, most of them had shut down. As of 2016, though tribes and the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) continue to run fifty schools nationwide, no Native boarding schools remain open in Minnesota.

There has been scant recognition of the boarding school era by the U.S. federal government and church denominations that initiated and carried out the schools’ policies. Neither has acknowledged, as the Canadian government did for its own boarding school program in 2008, that those policies’ purpose was cultural genocide or accepted responsibility for their effects. Pratt’s contemporaries viewed him and other enforces of assimilationist policies as heroes.

Few textbooks discussed Native boarding schools before the twenty-first century. In the 2000s, however, many historians study them as the tools of ethnic cleansing. The genocidal policies the schools’ staffs carried out aimed to destroy the essential foundations of the lives of American Native students. Their objective was the disintegration and destruction of the culture, language, and spirituality of the Native American kids under their care. The policies they implemented led to the deaths of thousands of students through disease, hunger, and malnutrition, and have left a legacy of intergenerational trauma and unresolved grieving in many boarding school survivors and their families across Indian country.

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. First published: June 7, 2016 | Last modified: July 9, 2021

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. First published: June 7, 2016 | Last modified: July 9, 2021Minnesota Story – Hidden History: Federal investigation generates new interest in M.N. American Indian boarding schools

For decades, the federal government took Native American children from their families and sent them to boarding schools around the United States, including to the one in Pipestone, Minn., a small, southwestern town eight miles from the South Dakota border. Those schools, most of which have been closed for decades, are now at the center of a new federal investigation. In June, the Department of the Interior announced a comprehensive review of the “troubling legacy” of American Indian boarding school facilities in the U.S. The Pipestone school is expected to be included in the probe, as well as the American Indian boarding school in Flandreau, South Dakota, 18 miles west of Pipestone. The investigation came as a result of the discovery of hundreds of human remains on the grounds of residential schools for indigenous children in Canada. The final report, expected in April 2022, will identify boarding school facilities in the U.S. and will examine any “known and possible student burial sites” near those grounds. The news of the mass graves in Canada has sent tribal leaders and native people in Minnesota into the archives, eager to learn more about what is being called the state’s “hidden history.” “There is a desire to know if there is a similar story, an unknown story,” historian Brenda Child said. Child, a Northrop Professor of American Studies at the University of Minnesota, is a leading expert on American Indian boarding schools. The Red Lake Nation member was the first to write about the American Indian experience in these facilities and is sharing her work with tribes across the state. “Tribal leaders in Minnesota want to know, did kids die in boarding schools in Minnesota or in other states where we sent our children?” she said (YouTube Description).

KARE 11, 2021 News: Minneapolis-based organization supports federal investigation into Native American boarding schools

Native American Boarding Schools: A Lost History (KARE 11 interviews UM, Morris’ Anishanabe Professor of Gabe Desrosiers)

“For decades, many American Indian children were forced to attend government-funded boarding schools designed to sever Native cultures, languages and traditions” (YouTube Description).

As hundreds of unmarked graves are uncovered at the sites of several former Canadian Indigenous residential schools, many are now calling for an investigation into similar sites that may exist here in the U.S.

Boarding School Healing

The Native American Rights Fund is pursuing strategies to support boarding school survivors; Native American children, families, communities; and tribal nations.

Elder Memories of “Indian Residential School”

Canada’s Orange Shirt Day

This is a very brief overview of the important work of Ms. Phyllis Webstad. I am posting the video below as it is short. Please spend some time researching and looking for videos of Phyllis’ presentations.

Kujo’s Kid Zone – Mini Episode 31– Orange Shirt Day/Residential School

Orange Shirt Day – this is a video for children. You will be surprised how much this will touch your own soul.

The Orange Shirt Story Read Loud by Miss Pole’s 3/4 Class

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q_sKiKom5F8

My Auntie survived residential school. I need to gather her stories before she’s gone

This long Story, produced by the CBD, is well worth the time. Due to COVID-19, so much went into this video. This is a testimony to the need to preserve stories. We hope you will consider sharing video time with your elders or elders in your community before their voices are gone.

Smithsonian’s Pocahontas: Beyond the Myth (Full Episode)

“The story of Pocahontas has been passed down through the centuries. Her relationship with John Smith has been characterized as a romance that united two cultures and created lasting peace. However, the life of this American Indian princess was anything but a fairytale. Join us as we look beyond the fiction and reveal the real story of Pocahontas, a tale of kidnapping, conflict, starvation, ocean journeys, and the future of an entire civilization” (YouTube Description).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9_zT6enTzA

Thanksgiving

Also, see this link: https://www.smithsonianchannel.com/special/behind-the-holiday-thanksgiving

Additional Online Resources

- FAQs from the U.S. Department of Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs: https://www.bia.gov/frequently-asked-questions

- Excellent Basic Education: https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/about/understandings#eublock1

- Ojibwe Lifeways, What can we learn today from early inhabitants of Minnesota who gathered and hunted wild foods to survive? by Dr. Anton

- Native Peoples of North America by Dr. Susan Stebbins

- The chapter on Religion and Spiritual Beliefs

- Cultural Documentation Training for Indigenous Communities by the Library of Congress Research Center

- History of Survivance: Upper Midwest 19th-Century Native American Narratives

- “The following is an exhibit of resources that can be found within the Digital Public Library of America retold through the lens of Native American survivance in the Minnesota region. Within are a series of objects of both Native and non-Native origin that tell a story of extraordinary culture disruption, change and continuity during 19th c., and how that affects the Native population of Minnesota today” (Minnesota Digital Library. http://www.mndigital.org).

Full Documentaries

-

- LIFE LAKOTA | The Cheyenne River Reservation

- “Over-The-Rhine International Film Festival – Grand Jury’s Short Documentary WINNER Life Lakota captures the state of the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota today. The Lakota culture is fading and their voices must be heard. Local leaders are taking action to educate the youth while organizations like the Sioux YMCA are helping kids stay above the influence of many of the extreme adversities that the reservation presents them. Lakota people are humble, proud and full of faith, we are honored to help tell their story. Produced by Vativ Media: Vativmedia.com” (YouTube Description, 2019).

- Lakota Daughters

- VOA News, the “Film documents life of women and girls of Pine Ridge Native American Reservation, South Dakota” (YouTube Description, 2020).

- LIFE LAKOTA | The Cheyenne River Reservation

Shorter Documentaries

-

- Pine Ridge, South Dakota –Inside an Indian Reservation Reeling From Poverty and the Pandemic

- “The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota is home to the Oglala Lakota nation — people whose ancestors survived generations of oppression and violence. Today, half live below the poverty line and many go without basics like running water. Life expectancy for Lakota men is 47 and for women is 53, lower than any country in the world. That was before the pandemic. NBCLX contributors Martin Markovits and Niko Kyriakou take us inside a Native American community fighting for its life” (YouTube Description, 2021).

- Lakota in America Documentary

- Pine Ridge, South Dakota –Inside an Indian Reservation Reeling From Poverty and the Pandemic

Glossary of Terms and Concepts

Communication loosely means “sharing and understanding meaning” or “making common” (Pearson & Nelson, 2000). Community and communication share the same root word, and in “making common,” we find a means to use verbal (words) and nonverbal (non-words) symbols to reduce uncertainty.:

Communication Competence: …(Cooley & Roach, 1984).

Cultural Appropriation: “Cultural appropriation describes the taking over of creative or artistic forms, themes, or practices by one cultural group from another; generally Western appropriations of non‐Western or non‐white forms. The act of cultural appropriation connotes cultural exploitation and dominance (OED). More broadly, cultural appropriation is the taking of intellectual property, cultural expressions, or artifacts, history and ways of knowledge from a culture that is not one’s own (Ziff).” (Quoted from: https://projecthumanities.asu.edu/content/cultural appropriation)

Culture:

-

- As Samovar, Porter, McDaniel, & Roy (2017) explain, “Culture is a set of human-made objective and subjective elements that in the past have increased the probability of survival and resulted in satisfaction for the participants in an ecological niche, and thus became shared among those who could communicate with each other because they had a common language and lived in the same time and place” (p. 39).

- Another definition from Lustig & Koester (2005) in their book, Among Us, explains that culture is a learned set of shared interpretations of beliefs, values, norms, and social practices that includes the behaviors of a large group of people. In so doing, culture links to human symbolic processes (p. 13).Cultural Appreciation: “A society that has many different cultural or ethnic groups. People live alongside one another, but each cultural group does not necessarily interact with each other. For example, in a multicultural neighborhood, people may go to ethnicity-specific grocery stores and restaurants but may not really interact with their neighbors from those ethnic groups. They simply co-exist in one environment” (Imania, 2022).

Cultural Competence: Williams (2001) defined cultural competence as “the ability of individuals and systems to work or respond effectively across cultures in a way that acknowledges and respects the culture of the person or organization being served” (p. 1).

Cultural Myth: “A cultural myth is a traditional story that holds special significance for the people of a given culture…A cultural myth often includes details of the life or philosophy of the culture that originated it….” (Rankin, 2022). See: https://www.languagehumanities.org/what-is-a-cultural-myth

Dominant Culture: “Whereas traditional societies can be characterized by a high consistency of cultural traits and customs, modern societies are often a conglomeration of different, often competing, cultures and subcultures. In such a situation of diversity, a dominant culture is one whose values, language, and ways of behaving are imposed on a subordinate culture or cultures through economic or political power. This may be achieved through legal or political suppression of other sets of values and patterns of behaviour, or by monopolizing the media of communication” (“Dominant culture,” n.d.). https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095725838

Land Acknowledgement: “What is a land acknowledgment? A land acknowledgment is a formal statement that recognizes Indigenous peoples as the long-standing occupants and caretakers of particular land or region. It offers respect for the enduring relationships that exist between them and their traditional territories. (“Land acknowledgment,” n.d.).

Language: “The system of spoken or written communication used by a particular country, people, community, etc., typically consisting of words used within a regular grammatical and syntactic structure; (also) a formal system of communication by gesture, esp. as used by the deaf. Also figurative” (Oxford English Dictionary, 2022).

Naming: The Harvard University Plurarlistic Project Archive quotes the St. Petersburg Times as follows: “…the naming ritual, telling the group that the elder or chief of a tribe has the ability to rename you, giving you an Indian name. Your Indian name can be used publicly, and it should say something about you personally. ‘Your Indian name needs to fit who you are and who you can grow into,’ said Duncan. A spiritual name is private and totally different. ‘It is between you and your maker” (Harvard University, 2001).

Works Cited

Arizona State University Project Humanities. (n.d.). “cultural appropriation: Critical dialogues on cultural awareness”. “Cultural Appropriation: Critical Dialogues on Cultural Awareness” | Project Humanities. Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://projecthumanities.asu.edu/content/%E2%80%9Ccultural-appropriation-critical-dialogues-cultural-awareness%E2%80%9D

Bakhtin, M. (1981). Discourse in the Novel. In M. M. Bakhtin. The Dialogic Imagination. Four essays. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 259-422

Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man”: R. H. Pratt on the Education of Native Americans | Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. (n.d.). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/teach/kill-indian-him-and-save-man-r-h-pratt-education-native-americans

Diversity and cultural competency | OER commons. Diversity and Cultural Competency. (n.d.). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/module/55424/overview

Dominant culture. Oxford Reference. (n.d.). Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095725838

Hamston, J. (2006). Bakhtin’s Theory of Dialogue: A Construct for Pedagogy, Methodology and Analysis. The Australian Educational Researcher, 33(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/13384.2210-5328

Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An Integrative Review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/ 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003