53 Un-grading

Un-grading

Authors:

- Dr. Elizabeth Harsma

- Dr. Darcie Christensen: Feedback, Self-assessment, and Professional Conduct

- Dr. Lauren Singelmann: Can Un-grading work in STEM courses?

- Dr. Rachael Hanel: Reflection – Mastery-Based Grading in Mass Communication

- Dr. Kelly Moreland: Reflection – Labor-based Grading Contracts in Composition

- Dr. Abigail Bakke: Resource – Prof. VB’s Un-grading Resources

- Dr. Kevin Dover: Literature review, Laissez faire grading

Published: August 4, 2023

This article includes personal narrative embedded in research-based recommendations. This document is not meant to be comprehensive or prescriptive, but offers perspectives and ways you might incorporate these perspectives into your teaching.

What is un-grading?

Un-grading is a term that refers to a variety of assessment techniques that do not use traditional percentage, points, or letters scales to rank and rate students. Instead, un-grading methods focus on feedback and learning. Un-grading might also be called going gradeless, grade-free, or de-grading.

Un-grading methods vary based on subject matter, teaching philosophy, and course design. In other words, un-grading is unique to the instructor and the class. Some scholars do not include methods such as mastery-based or specifications grading within the umbrella of un-grading, because these methods use points to indicate learning progress (Talbert, 2023). We include these methods as un-grading practices because they focus on feedback and learning mastery, rather than ranking or rating.

Examples of un-grading

Un-grading methods include:

- Labor-based grading contracts (Inoue, 2022)

- Mastery or standards-based grading (Zimmerman, 2020)

- Specifications grading (McKnelly, Howitz, Thane, & Link, 2023)

- Portfolios (Burnham, 1986)

- Laissez faire grading (Dover, n.d.)

- Co-creation (Katopodis, 2018)

- …and more!

Why un-grade?

Traditional grading approaches that rank and rate students on a scale of 0 to 100 or label with a letter or symbol have been critiqued based on a range of factors:

- Inconsistent meaning of grades. Research on grading demonstrates poor inter-rater reliability in traditional grading practices. An “A” paper to one faculty is a “C” paper to another. Blum writes “it is common for grades to be inconsistent, subjective, random, arbitrary” (p. 11).

- Grades are not effective feedback. Grades do not provide specific and actionable feedback to help learners understand their learning successes and gaps.

- Grades do not effectively communicate individual learning progress. For example, a learner who comes in with less background knowledge and works hard and makes great progress, may still earn a lower grade than someone who came in with higher levels of background knowledge and works very little.

- Grades have unintended negative consequences. Grades center teacher authority. Grades promote extrinsic motivation rather than intrinsic curiosity. Grades discourage risk taking and creativity. Grades may be a contributing factor in academic dishonesty.

- Grades only appear concrete and objective. Blum writes: “Grading promotes a deleterious focus on an appearance of objectivity (with its use of numbers) and an appearance of accuracy (with its fine distinctions) and contributes to a misplaced sense of concreteness” (p. 14).

Un-grading assessment practices may also support anti-racist teaching methods (See Kishimoto, 2018). Cheema (2022), librarian and author of library guide antiracist pedagogy and praxis writes:

“Alongside such practices as developing inclusive syllabi that diversify the canon and creating effective teaching modules that engage students across differences, antiracist pedagogy also includes developing fair and inclusive assessment practices that measure student learning from a variety of parameters beyond the culturally limited models of white middle class and upper-class achievement.”

Can I un-grade if final letter grades are required?

Assigning grades at the end of a course is a requirement in many Universities. It is recommended that you learn about pertinent policies and requirements in your specific context.

Many educators have asserted that there are many ways un-grading can be applied within a traditional grading system, for example:

- No-Grades Course: You can un-grade an entire course (except the final grade).

- Grade-Free Zones: Un-grade a category of learning activities, for example daily homework or weekly practice quizzes.

- Un-graded Activities: Un-grade one activity or one assignment.

Can Un-grading work in STEM courses?

Dr. Lauren Singelmann, Iron Range Engineering, Minnesota State University, Mankato responds:

Yes! Un-grading can work in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) courses. However, you may find that certain un-grading strategies may work better in some courses, whereas other un-grading strategies might work better in other courses. When implementing un-grading in any course, it’s important to think about what learning outcomes you hope students take away from your course and choose a grading scheme that supports those learning outcomes. In many STEM courses, there are specific outcomes that you want students to achieve where it is easy to tell if the outcome was met or not (e.g., solving a differential equation, applying Kirchhoff’s Laws to simple circuits, or identifying the muscles in the body). However, there are also outcomes that are more complex than right or wrong (e.g., using problem-solving skills to make a diagnosis, participating in engineering design, or conducting research).

If your course is more focused on helping students develop fundamental knowledge, an alternative grading strategy that might work well is standards-based grading. For this strategy, the course is built around a list of knowledge and procedural skills that you want students to develop, and their grade corresponds to how many of those knowledge and skills they have successfully demonstrated. For example, in an introductory physics course, students may still be taking quizzes to show their learning about kinematics, but they are given multiple chances to show that their learning. Rather than the focus being placed on earning a desired grade, the focus is placed on learning the knowledge and skills needed to be successful in future courses and careers. If a student is missing a key piece of knowledge or a skill, they get more chances to demonstrate their learning rather than just moving on. This strategy gives all students a chance to be successful for both their current course and future courses by clearly communicating the necessary knowledge and skills needed.

If your course is more focused on developing complex skills, an alternative grading strategy that might work well is labor-based grading. For this strategy, students earn a grade based on the amount of work that a student completes. They get feedback on the quality of their work throughout the course, but ultimately their grade is dependent on the time and effort they put into the learning process. This strategy works well when students are working on complex skills where the answer isn’t necessarily right or wrong. For example, if they are working on conducting a research study or completing an engineering design project, learning and success might look different depending on each student’s focus. They are still gaining valuable feedback on their work, but their grade is not dependent on an instructor’s opinion of their final work, but rather on the work they put into their learning process.

What are examples of un-grading?

These are some examples of un-grading practices (See also Blum, 2020 for more examples!).

Feedback, Self-Assessment, and Professional Conduct in Engineering

Dr. Darcie Christensen, faculty in the Iron Range Engineering program at Minnesota State University, Mankato shares some of their un-grading assessment strategies:

The primary focus of all feedback given on deliverables in my course is qualitative formative feedback, which leads up to students being prepared for the summative deliverables of project reports/presentations and oral examinations. The qualitative formative feedback supports the quantitative score that is given for each deliverable.

The feedback (quantitative & qualitative) for these low-stakes deliverables throughout the semester is not impacted by timeliness so that all feedback given on each deliverable is focused on quality of the deliverable, not on student behaviors. At the end of the semester, students are able to do self-evaluation and decide for themselves what their professional conduct score for the course should be.

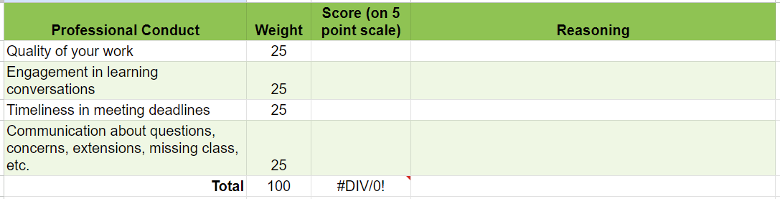

The factors that contribute to the professional conduct score are timeliness, quality of work, engagement in learning conversations, and communication habits. Students are given time to reflect on this up until their oral exam. After completing their oral exam, the instructor and the student discuss and reflect together on what the agreed upon professional conduct score is and what can be improved on for the future.

The professional conduct score contributes at least 20-25% of their final grade, but no letter grades are calculated for deliverables until the very end of the course. While this approach still includes “grading” and scores, it keeps students’ performance on the individual course deliverables about the actual completion of that deliverable and students are able to assess their own professional conduct to complement the overall course grade.

Below is a sample rubric using a 5-Point scale (which is implemented throughout the Iron Range Engineering program), which students are familiar with the qualitative interpretations of and its translation to a “traditional” grading scale, which will be the final output for transcripted [final] grades.

Labor-Based Grading Contracts

Labor-based grading contracts offer students transparency and choice to earn the grade they want. With labor-based grading contracts, students earn a grade in the course by successfully completing all the criteria/tasks required at the grade level they have chosen.

Students are evaluated based on labor rather than on the quality of their work. Grading based on labor does not mean a lack of rigor. Students are required to meet the criteria for each task for it to be considered complete. However, the criteria do not address the quality of work – they focus on meeting learning goals of the task. And students are offered ample practice and iterative feedback to improve their learning.

One foundational educator and writer in labor-based grading contracts in English composition is Asao B. Inoue. Inoue (2022) asserts that labor-based grading contracts can be an anti-racist assessment practice and a means of addressing a need for feedback that prompts learning that curtails the arbitrary judgement inherent in ranking/rating approaches to assessment.

Inoue (2022) shares this example labor-based grading contract that outlines the labor required to earn a final letter grade in an introductory composition course. To earn an A, students must also complete additional or supplemental tasks above the required assignments.

- NPD – Non-Participation Day

- LA – Late Assignments

- MA – Missing Assignments

- IA – Incomplete Assignments

|

|

NPD |

LA |

MA |

IA |

|

A (Aid/Support) |

3 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

B (Default) |

3 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

C |

4 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

|

D |

5 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

|

E/F |

6 |

6 |

4 |

2 |

Table Description: Labor-Based Grading Contract. The left column lists final course grade from A to F. The row labels indicate criteria for earning that grade. Each cell indicates how many items from each category a student can have to earn that letter grade. For example, to earn a final grade of C, a student can have no more than 4 non-participation days, 4 late assignments, 2 missing assignments and 0 incomplete assignments.

Mastery or Standards-Based Grading

To address ambiguity in grading methods and subsequent variable proficiency levels upon course exit, Zimmerman (2020) implemented a standards-based grading (SBG) approach in an undergraduate gateway math course, College Algebra.

At the center of the SBG approach was development of a mastery-based or standards based grading rubric with 4 levels, mastery, proficient, developing, and novice, as well as a no evidence of understanding level.

The standards based grading approach was frontloaded with a comprehensive re-design of the course, including:

- crafting specific and measurable objectives for each unit,

- creating a SBG rubric for evaluating quizzes and exams,

- writing assessment questions for each objective,

- creating new textbook content using remixed OER (Open Educational Resources) to allow for exact alignment with objectives, and

- creating materials such as in-class exploration activities that promoted “level 4 mastery” practice with guided reflection and discussion to help students move beyond the memorizing steps approach to math.

Students in the SBG course were encouraged to complete no points practices that provided feedback but not the answer and engage in 4 un-graded self-assessments which included solutions and a guide for self-scoring their practice with the SBG rubric.

The SBG rubric was used to assess performance on quizzes which assessed 1 to 3 learning objectives and unit exams which assessed 6-8 objectives. If the exam score on the objective was higher, that score was kept as the grade for the objective. If the quiz score was higher, an average of the two scores is kept as the grade.

The final exam was designed to allow students to re-assess their mastery in a way that was feasible for thousands of students taking these courses. Students were required to re-test on any objectives they had scored a “level 2 developing” or lower and could choose to re-test on other objectives if they chose. Zimmerman (2020) worked with their department to build a custom online gradebook that would provide students’ ownership of the learning process. They also developed a way to use a student completed form and the gradebook scores to generate individualized final exams for students.

Will students understand un-grading?

Many students will be unfamiliar with un-grading practices. Here we share are some strategies to help students understand the why and how of un-grading, including:

- On-board students,

- Check-in with the whole class and adjust,

- Individual student conferences, and

- Data-driven change,

- …among other ideas!

On-board students

- Introduce your un-grading approach, share why you are using this approach.

- Explain the un-grading methods in your course with examples.

- Review your un-grading approach regularly, for example, share how each assignment fits into your un-grading method.

Check-in and adjust

Ask for feedback from all students about their understanding of un-grading in your course and answer any questions or clarify items as needed.

For example, create an anonymous survey that ask students to rate their agreement with statements such as:

- I understand how I will be graded in this course.

- I know how to track my progress toward earning the grade I want in this course.

- The expectations for earning each grade level in this course are fair and reasonable.

- I understand what to do with peer and instructor feedback I received on my course work.

- I understand the expectations for resubmission of course work.

- (Open-ended) Please explain why you selected the levels of agreement you did:

- (Open-ended) What questions do you have about grading in this course?

Student conferences

Consider a one-on-one conference with students to discuss their learning progress and current grade in the course. Some ideas:

- Offer synchronous online meetings using a booking app or tool for quick scheduling.

- Consider scheduling conferences during class times to support students with busy schedules.

- Schedule conferences during your office hours to support students finding and using your office hours.

Data-driven change

Use course data to make decisions about changes or updates to un-grading criteria.

- For example, looking at attendance data, you might find perfect attendance is not a reasonable expectation to earn an A for that student group.

- When examining quiz performance, instead of dropping 2, you might drop the 4 lowest practice quiz scores to avoid penalizing learning mistakes that occurred early in the semester with that group of students.

Getting started reflections on un-grading

Here are some helpful reflections and comments from colleagues on getting started with Un-grading:.

Mastery-Based Grading in Mass Communication

Dr. Rachael Hanel, faculty in Mass Communication at Minnesota State University, Mankato shares their experiences with mastery-grading:

I think my biggest question was, and the question I get from others, is how to set up the D2L Brightspace Grades to accommodate labor-based grading. After doing it for a couple of semesters I think I’m getting the hang of it, but it still takes me a little bit of thinking it through.

Another thing I can think of is what about those students who are straddling a line between “A” work and “B” work, or “B” and “C,” etc. I think most students probably fall neatly into their categories, but I suppose there will always be some outliers where the assessment of their labor is a little more complicated.

Un-grading and D2L Brghtspace

See these tutorial video playlists to learn more:

Labor-Based Grading Contracts in Composition

Dr. Kelly Moreland, program director of composition at Minnesota State University, Mankato shares a reflection on common challenges to implementing labor-based grading contracts:

I think sometimes it’s difficult to wrap our minds around final grades not being based on the quality of assignments produced. I often hear, “but the student wrote such a good paper!” But if they didn’t do the process work for that paper, or if they missed other formative assignments in the class, the missed work is going to be what their grade is based on. It’s a different kind of fair.

Related, the students who tend to be against labor-based grading are ones who have always traditionally done well in school without putting in much work. One of the hardest and most rewarding parts of using this grading system is the opportunity to teach students about inequities in education/grading and help them start to reframe their thinking about the role(s) privilege plays in their experiences. It doesn’t always work, but that’s my go-to response when students express disdain for the grading system.

Also: It’s totally OK to renegotiate your contract during the semester! If mid-semester you see that the contract is not working—e.g., too many students are in danger of not passing the class, or no one is able to earn an A—work with your students to change it. In my experience they come up with pretty reasonable expectations for themselves and others.

Even more un-grading resources

Un-grading: An Introduction

- Description: Transcript of a presentation that introduces the why and how of un-grading, which begins with questioning grading and trusting students. Centers on the pivot to remote instruction from 2020 onward but shares timely and applicable concepts and strategies.

- Citation: Stommel, J. (2021 June 11). Un-grading: An Introduction. Retrieved from: https://www.jessestommel.com/un-grading-an-introduction/

Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies

- Description: Inoue critiques writing assessment through an antiracist lens. Inoue analyzes and proposes a different approach to writing assessment with a focus on labor-based contract grading. See also Labor-Based Grading Contracts in the Compassionate Writing Classroom.

- Citation: Inoue, Asao B. (2015). Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future. The WAC Clearinghouse; Parlor Press. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2015.0698 Retrieved from: https://wac.colostate.edu/books/perspectives/inoue/

Un-grading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead)

- Description: A book that critiques traditional grading systems and offers an introduction to Un-grading assessment approaches. Additional chapters serve as detailed description and experience implementing Un-grading in various disciplines including composition, chemistry, and a point-less math course, among others.

- Citation: Blum, S. D., & Kohn, A. (2020). Un-grading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead). (S. D. Blum, Ed.; First edition.). West Virginia University Press.

Prof. VB’s Un-grading Resources

This is a resource shared by Dr. Abi Bakke, Technical Communication at Minnesota State University, Mankato:

- Description: Resources for alternative or equitable grading practices in first-year composition. Primary focus on labor-based grading, additional focus on collaborative and self-assessment.

- Citation: VonBergen, M. (n.d.) Prof. VB’s Un-grading Resources. Retrieved from: https://www.craft.do/s/nYRjrEPD88Xmzy

References

Blum, S. D., & Kohn, A. (2020). Un-grading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead). (S. D. Blum, Ed.; First edition.). West Virginia University Press. Read for free with a library card at Minnesota State University, Mankato

Burnham, C. “Portfolio Evaluation: Room to Breathe and Grow.” In Charles Bridges (Ed.), Training the Teacher of College Composition. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, 1986.

Cheema, Z. (2022). Introduction to Antiracist Pedagogy and Praxis. American University Library Guides. Retrieved from: https://subjectguides.library.american.edu/c.php?g=1025915&p=7749898

Dover, K. (n.d.). Un-grading Resources: Laissez faire grading method created by Dr. Dover. [Presentation]. Un-grading Certificate. Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Minnesota State University, Mankato.

Inoue, A. B. (2022). Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom, 2nd ed. The WAC Clearinghouse; University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2022.1824 Retrieved from: https://wac.colostate.edu/books/perspectives/labor/

Kishimoto, K. (2018) Anti-racist pedagogy: From faculty’s self-reflection to organizing within and beyond the classroom. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(4), 540-554. DOI:10.1080/13613324.2016.1248824

McKnelly, K.J., Howitz, W.J., Thane, T.A., & Link, R.D. (2023, July 5). Specifications Grading at Scale: Improved Letter Grades and Grading-Related Interactions in a Course with over 1,000 Students. ChemRxiv. Cambridge: Cambridge Open Engage. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372148051_Specifications_Grading_at_Scale_Improved_Letter_Grades_and_Grading-Related_Interactions_in_a_Course_with_over_1000_Students

Talbert, R. (2023). Un-grading in STEM Courses. Zeal: A Journal for the Liberal Arts, Vol. 1, No. 2 (pp. 112-116). Retrieved from: https://zeal.kings.edu/zeal/article/view/27

Zimmerman, J.K. (2020) Implementing Standards-Based Grading in Large Courses Across Multiple Sections, PRIMUS, 30:8-10, 1040-1053, DOI: 10.1080/10511970.2020.1733149