2 Native American Habitation

There is a distinctive hackberry tree on the Kasota Prairie (see Figure 4.) It is distinctive for a number of reasons. First, it is one of only a few trees. It stands alone on a little hill with only prairie around it and the wooded bluff of the Minnesota River in the background.

Second, it seems to have grown out of the base of a limestone outcrop. One hot July day many years ago, I was admiring how it grew out of stone when something else caught my attention. It looked like there was a drawing that had been carved into it. Indeed, I later learned that it was a petroglyph representing a thunderbird. Petroglyphs were made by Native Americans. Their purpose and what they mean is not clear. The Jeffers Petroglpyhs, a State Park in southwestern Minnesota, attracts thousands of visitors, where this art abounds. But this hackberry tree petroglyph is the only one that I know of on the Kasota Prairie. Over the years, it has become weathered and worn, but every time I see it, I think of who might have carved it and when, and of the other Native Americans who lived on the Prairie.

The First Americans

Archaeologists have identified four main Prehistoric Native American cultures. A brief description of each of these cultures and their associated diagnostic artifacts are provided by the late Minnesota archeologist Elden Johnson[1] and Michael Scullin,[2]a former archeologist at Minnesota State University, Mankato, who has done extensive excavations on these cultures. The oldest is the Big Game or PaleoIndian; next the Eastern Archaic; followed by the Woodland; and finally, the Mississippian. One way these cultures have been distinguished is through the types and varieties of artifacts that have been found in archeological digs. This characteristic has been described in many studies.[3] Variations in the size and shape of stone weapons, such as projectile points, and tools, such as axes, mauls and gouges, and changes in the styles of ceramics can all help identify a particular prehistoric culture. What prehistoric people lived on the Kasota Prairie?

Big Game (Paleolndian)

As the glaciers retreated, PaleoIndians were hunting, fishing and using a variety of natural resources. We know that at this time, North America was well stocked with large animals such as the woolly mammoth, giant buffalo, and mastodon. The hunting of these big game animals characterizes this culture; hence,their name. Most archaeological sites in Minnesota which have been excavated from this time period are so-called “kill sites” at which the Paleolndians killed, butchered, and consumed large animals. The use of fire seems to have been an important hunting weapon, as I have earlier discussed. By setting fires, mastodons and mammoths could be driven into river valleys or rocky ravines and become crippled, making these big animals vulnerable. To kill them, Paleolndians made a distinctive projectile point. These spear points were grooved or fluted length-wise on the stone to fit on to a spear. This craft is now called “flintknapping” and to do it requires much practice. I have tried flintknapping, and believe me, it is a craft that only a few can master. Flint or chert, a knife-like rock, must first be quarried or dug out of a rock formation or obtained through trade, then using a deer bone or antler by a process of chipping and flaking, a sharp edge is put onto the rock. The edges of these stone weapons can be as sharp as steel. My assumption is that only certain craftspeople of the PaleoIndians became experts at this and that their skills and resulting projectile points were highly valued. When a fluted point is found, you can be sure it was made by a PaleoIndian. It is diagnostic, unlike the shape of the common arrowhead. In addition to spear points and drills, chert scrapers to aid in the butchering and cleaning of hides were also made. With fire and these finely-crafted spear points, then, PaleoIndians lived by following and slaughtering big game animals. It is very possible that some day archeologists will discover a kill site such as this somewhere on the Kasota Prairie None has been found so far.

Eastern Archaic

After the Paleolndian culture, it seems that prehistoric people began to settle somewhat more permanently in particular places, for longer periods of time. They also began to diversify their hunting and gathering lifestyle according to the availability of various resources. This change is reflected in a greater assortment of stone tools and weapons. This is the so-called Eastern Archaic Period and archeological sites contain not only the chert projectile points, drills, and scrapers, but what are called ground stone tools such as axes and hammer stones. The nutting and milling stones were used like a mortar and pestle to grind seeds, grains, or crush nuts. The flint axe found at some sites indicates a tool for digging roots or planting and hoeing. The bolas stones were thought to be used as weights to attach to throw nets in fishing. The atlatl weights of polished stone such as slate were used as weights on spear throwers or atlatls to gain more distance and perhaps accuracy. All in all, the increase in quantity and variety of artifacts from this culture suggests more varied occupations of certain environments, which would change at different times of the year. Archaic camp sites are often found near a body of water, like the Minnesota River or lakes. In the summer, resources of fish, ducks, geese, and swan could be harvested by netting and berries, nuts, and wild fruits gathered and prepared. During the fall and into the winter months, the village or camp could move into a more sheltered wooded environment. A different assemblage of resources was then available, such as squirrel, rabbit, and deer.

Woodland

About three thousand years ago other cultural changes occurred. It appears that a more complex social system was evolving with Native Americans diversifying their livelihood even more. This is the so-called Woodland culture which archeologists divide into Early, Middle, and Late Periods. In addition to the previous cultures’ stone weapons and tools, others have been added, such as celts, stone smoking pipes, game balls, and rings. Pottery makes its first appearance in archeological sites at this time period. Clay pots were used for cooking and storage of foods, and also as bowls and for water storage. Burial mounds also make their appearance in this culture. Burial mounds were a mortuary practice that began around 800 B.C. It has been estimated that approximately 15,000- 25,000 burial mounds were made in Minnesota. Three typical mound locations have been found: burial mounds along river bluffs, on glacial terraces, and those found along lake shores.

G.A.Lothson[4] has identified 27 burial mounds in Le Sueur County. I have also located, mapped and measured a number of burial mounds in the Minnesota River Valley.[5]

Although burial mounds were made in a variety of shapes, most in Minnesota were circular, although linear shapes were also used, likely for multiple burials. Some, however, were constructed in the shape of birds and animals, so-called effigy mounds. The Effigy Mounds National Monument in Iowa contains a grand assortment of these burials. In the Minnesota River Valley effigy mounds in the shape of birds have been located and mapped in Sibley County near the ghost town of Faxson. Professor Jane Buikstra’s [6] many excavations in the Lower Illinois River Valley revealed how a prehistoric burial was constructed. After a funeral, the body of the deceased was laid in a shallow pit or tomb lined with wood or limestone slabs. Over this, basketfuls of soil would be placed to form a mound. Larger mounds would have several layers of burials, each on top of the other. Most burial mounds in the Minnesota River Valley are of a single burial, but some can contain so-called bundle burials where the flesh is removed and the bones are “bundled” or bagged. An assortment of these burials are often located together as a cemetery near a village.

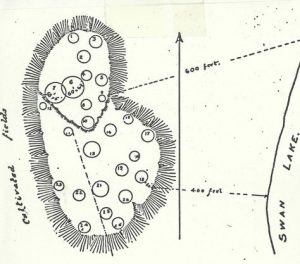

An example of burial mounds in a cemetery complex in the Minnesota River Valley is the Poehler Mound complex, located west of Nicollet, Minnesota. It was identified and mapped by Winchell[7] and later excavated and studied by Professor Lloyd Wilford and archeology field school students in 1954.[8] In the 1950’s and in fact up until the Reburial Act [should this be Native American Graves and Repatriation Act?] It was possible to excavate human remains for scientific study. Thus, Professor Wilford was not alone in doing this. There did not seem to be any moral or ethical barrier involved in these excavations at the time either. The Poehler cemetery consisted of a group of twenty or more mounds located on a high hill at the southwest corner of Swan Lake (see Figure 5).

An example of one mound that was excavated showed that it consisted of two bundle burials of adults and an infant burial. The adult burials were disturbed meaning that they had been damaged either by plowing or looting. Also found was a large rim shard of a clay pot.[9]

Mississippian

The final prehistoric culture in the Minnesota River Valley was the Mississippian. For these people, corn farming and a more vibrant and varied village life became a distinguishing characteristic. Rather than being solely dependent on hunting and gathering resources, growing corn for food became the principal means of sustaining life. These people lived in villages surrounded by their agricultural fields. Their earliest village sites date back to about one thousand years ago, and the latest may be in the sixteenth century. Archeologists are not sure when this culture period ended, and the historic Dakota Indian culture began.We do know that at some point there was a transition to an historic Indian people such as the Dakota in the Minnesota River Valley. The Mississippians were also noted for building immense flat-topped temple mounds, the most famous being the Cahokia Mound in southern Illinois near St. Louis, Mo. These temple mounds may have been the stages for ceremonial practices or the homes or final resting places of the so-called chiefs or elites of the surrounding villages. No such mounds have been found in Minnesota. The variety and intricacy of the Mississippian people’s pottery was also more advanced over the previous Woodland Culture.

Before I end this chapter on Native Americans, I want to relate to you an incident that happened some years ago that had a lasting impression on me. Numerous skeletal remains, flint, and pot shards had been brought to the surface doing field cultivation of the Poehler Mound that I previously talked about. I can attest to this as I know that it was used as an artifact and skeletal collecting site. To my regret, I also have participated in the surface collection of artifacts and skeletal remains here. It was part of an archeology class that I was teaching 30 years ago. I later became concerned about the moral and ethical implications of doing this collecting and wanted to somehow make amends for my action to the Native American people. I finally got up the courage to approach this subject with Chief Ernest Wabasha of the Dakota.[10] He did not lecture me, nor chastise me, but rather set up a time when the skeletal remains I had found could be reburied. I had stored the bones in a plastic bag in my garage but thought it extremely unfitting to present them to him this way. I had a carpenter friend make me a small box, or coffin as it were, to contain the skeletal remains. After a long and moving ceremony at the Wabasha home, much like a wake, the bones were reburied in a church cemetery near the Lower Sioux Agency Reservation at Morton, MN. A hole had already been dug. I was astonished that the size of the hole perfectly fit the size of the coffin box I had made. The Native Americans had no idea I was bringing their ancestors to their grave this way and I had no idea they were preparing a burial plot of the same dimensions. Was it foreordained that we conspired to give them this reburial? I don’t know, but I am grateful to Chief Wabasha for giving me the opportunity to make my transgression right.

Archeological Sites on the Kasota Prairie

There is archeological evidence that three of the four prehistoric people inhabited the Kasota Prairie. As part of their mining operation on the Prairie over 20 years ago, the Unimin Corporation hired the firm, Archeological Research Services, headed by Christina Harrison, to do an archeological study of their proposed new mining site.[11] During the summer and fall of 1996, the firm conducted two cultural resource investigations. Eight sites were identified by a variety of archeological methods, including surface reconnaissance and shovel testing. Three sites in particular, two habitation and one a possible lithic (stone) processing area, were shown “to possess enough physical integrity and research potential to be considered eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.”[12] Let me try to interpret some of the academic jargon in this statement. What it means is that these Native American sites appeared to be undisturbed for many years. I believe this is what “enough physical integrity” means. These sites were deemed so significant that the archeologists recommended that they be preserved by putting them on the National Resister of Historic Places. Now, specifically, what did they find?

The so-called Vetter I and Vetter VII sites yielded nearly 400 artifacts, mostly chert flaked tools such as hide scrapers, engravers, and knives. There were also grinding stones, hammer stones, and smoothers and polishers, made out of granite and basalt. These were identified as “habitation sites,” meaning Indians were living there. Again, to quote from the Archeological Research Services report, “Their relatively high number (i e. of these stone tools) suggests that a fair amount of hide and food preparation took place.”[13] I will comment later on this statement.

The Vetter IV site was identified as a possible lithic (stone) work area with people manufacturing tools from Prairie du Chien/Oneota oolitic chert. This is a chert that is not found all over the Minnesota River Valley. It is localized and where I have found it, it is in the form of nodules embedded in massive Oneota limestone rock outcrops. It is readily identifiable by the many small oolites in its composition and can be broken from these outcrops and made into knives, arrowheads, thumb scrapers, drills, and many other stone tools. It was an indispensable means for hunting and processing the meat and bone of these animals,such as skinning and butchering. Out of nearly 400 stone tools from the Vetter sites, all but 6% were of this material.[14] Either they quarried this chert from from some other area or found a source nearby. It is remarkable that an area as small as the Kasota Prairie could have been the location for one of these stone manufacturing sites. In addition, excavations unearthed sixty grindstones, hammer stones, smoothers, and polishers mostly of granite and basalt rocks readily available along the Minnesota River and tributary streams.

Other burial mounds were also uncovered. The Meyers Burial Mounds are situated just west of the town of Kasota at a location above the Minnesota River. They are very close to the three previously described archeological sites, suggesting that this immediate area was likely a long-term village habitation of the Woodland people. In its Conclusions and Recommendations, the Report on Cultural Resource Investigations stated “that considering the impact on the Minnesota River Valley . . . undisturbed river terraces like the project area (of the Vetter sites) are becoming a rarity. The PRESERVATION OF THESE LOCALITIES WITHIN A PROTECTED EASEMENT CONSTITUTES A SIGNIFICANT CONTRIBUTION TO FUTURE RESEARCH IN THIS AREA (italics mine).

In summary, these archeological investigations, and don’t forget the petroglyph, provide evidence of prehistoric Native American occupation on the Kasota Prairie. And many of them inhabited this area over a long period of time. Think about this. The proposed Unimin mine site where the sampled archeological sites and burial mounds are found is only 363 acres in size. This is only a fraction of the total area of the Kasota Prairie. If the results of these archeological investigations were extrapolated to the entire Prairie, it is quite possible that many more sites would be found. How many prehistoric people would this translate to? Clearly, considerably more people lived on the Kasota Prairie in Prehistoric times than now. There is no question in my mind once I read these archeological studies that here was a prime location of Native American habitation. But why? What would have made this place so attractive to them? For one thing, they “lived well on the edge.” Let me explain in the next chapter.

- Elden Johnson, Prehistoric Peoples of Minnesota, Minnesota Historical Society, St.Paul, Mn, 1969. ↵

- Michael Scullin, Prehistoric People of Southern Minnesota. n.d. Manuscript. ↵

- Harriet Smith, Prehistoric People of Illinois, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, is one such illustrative source. ↵

- G.A.Lothson, “The Distribution of Burial Mounds in Minnesota," The Minnesota Archeologist, vol .29, no. 2., 1967. ↵

- Bob Douglas, “Burial Mounds in the Minnesota River Valley,” Currents, vol VII, 1985, pp. 30-35. ↵

- Felicia Antonelli Holton, “Secrets of the Mound- Builders,” The University of Chicago Magazine, Spring 1989, pp. 7-13. ↵

- N.H.Winchell, The Aborigines of Minnesota, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN, The Pioneer Company, 1911. ↵

- Lloyd Wilford, Elden Johnson and Joan Vicinus, Burial Mounds of Central Minnesota: Excavation Reports, Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul, MN, 1969. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Interview with Chief Ernest Wabasha, September 2000, Traverse des Sioux History Center, St.Peter, MN. ↵

- Christina Harrison, Report on Cultural Resource Investigations Within Proposed Unimin Corporation Mining Site (Vetter Mine), Kasota, Le Sueur,Minnesota, Archeological Research Services, 3332 18th Avenue South, Minneapolis, MN, December 1996. ↵

- Ibid, p.7. ↵

- Ibid, p. 8. ↵

- Ibid, p. 10. ↵