5 Mining the Limestone

An “Accidental” Discovery

As was previously discussed, one of the first businessmen in the Kasota area was Joseph W. Babcock. We learned that he was awarded a Federal Government contract to deliver mail from St. Paul, Minnesota to Sioux City, Iowa. This postal job was only one of his entrepreneurial endeavors. He also made money by cutting, sawing, and selling lumber for the growing towns of Kasota, St. Peter, and Mankato. One day, while digging the foundation for a sawmill, rock was struck. The lumbermen began digging up this rock, and as they say, the rest is history. As it turned out, they had accidentally dug into one of the largest and most useful construction rock formations in the history of the United States. This rock, scientifically known as Oneota dolomite or more generally limestone, occurs underneath the Kasota Prairie to depths of over 100 feet. And to top it off, no pun intended, it is near the top of the ground. This makes mining much easier and thus, less expensive. The thin topsoil which made for such poor farming, made the stone very accessible to mine. An undeveloped or loosely bedded top layer of limestone, called overburden, was first removed and most of it crushed for road building. Below this low grade formation was the solid, thick-bedded dolomite that became a prized construction stone of great durability, owing to its high magnesium and dolomite content. It is also a beautiful stone occurring in a range of colors from beige to pink. Used for building, it can be left in its natural form with a rough texture or polished.

Early Mining History

In 1852 Babcock began quarrying this stone for a variety of uses including residential and commercial construction. The weight of the limestone necessitated that only a limited amount of it could be mined and processed in the early years as it was difficult to load and haul overland by wagon (see Fig. 6). In addition, the mining and loading methods were very time consuming and expensive. As a result, only two quarries were in early operation; one by Babcock, and the other, the Breen Quarry, operated by Rueben Butters.[1]

In the later 1800s, the industry made a great leap forward, largely because of the number of railroads that came through the Kasota Prairie. As noted in the previous chapter, these were the Chicago, St. Paul and Omaha, the Winona and St. Peter, and the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific. No longer did the stone need to be hauled exclusively by horse or oxen and wagon. Now, it could be loaded onto rail cars and hauled much greater distances at a much lower cost. A system of derricks, ramps, and horse drawn pulleys were used to lift the stone from the mine. The blocks were then hauled by wagon a short distance to the railhead and slid off the wagons onto a dock where they would be loaded onto the rail cars.

Another added value was that the stone was also used by the railroad companies themselves.The durability and hardness of the limestone made it an excellent choice for the foundations for underpasses, trestles, and grades. It replaced timber for these uses.

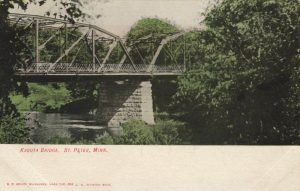

The result was that the railroads had a stake in limestone mining development as well. Some railroad owners, in fact, became owners of the mining companies. As a testimony to the stone’s durability, many of these trestles can still be seen along the long-abandoned rail lines. Most impressive are the limestone supports where a bridge once spanned the Minnesota River between St.Peter and Kasota, which are still standing (see Fig. 7).[2]

Kasota Stone, as it came to be called, soared in demand. Charles Babcock, Joseph’s son, eventually became the head of the company. In 1889 he teamed up with T. S. Wilcox to form the Babcock and Wilcox Company.[3] Wilcox had developed a method for polishing the Kasota Stone so it appeared like marble. The Babccock/Wilcox employees in July 1885 were paid a high wage of $1.75 and a low of $1.00 per day.[4] The office, blacksmith shop, and other buildings and the quarries were located at what is now a dump site in Kasota. Charles Babcock later purchased the Breen Stone and Marble Company for his three sons, Clifford, Frank, and Fred. It was located where the former Door Manufacturing had its company south of the downtown.[5]

Lime Production

A secondary spin-off business from the limestone industry was the production of lime. It was used as the principal binding agent in mortar. To “fix or hold” the stone in place whether in building construction or for a railroad trestle, some type of mortar was needed. Because it is so readily made by burning limestone, lime must have been known from the earliest times. The Chinese are believed to have manufactured the strongest mortar by adding “sticky rice” to the lime. Along coastal Georgia and South Carolina a substance called “tabby” was manufactured in the Antebellum plantation period. It consisted of equal parts water, sand, crushed oyster shells and burned oyster shells. The burned oyster shells produced lime which was the binding agent or mortar in “tabby.” Lime was produced locally in Kasota by the calcination or burning of limestone at a very high temperature in a kiln. As far as I know, no “sticky rice” was added.

There is at least one remnant of a lime kiln on the Kasota Prairie. It is located near the Vetter Stone Company headquarters and is typical of most lime kilns. Generally, it was a square-shaped building, with a burning chamber made with an air inlet at the base known as the “eye.” Limestone rock was crushed, often in the early days by hand, just as the plantation slaves crushed oyster shells. It was smashed into ideally two inch lumps and loaded into the kiln. Successive layers of rock and firewood were built up in the kiln on grate bars above the “eye.” When loading was complete, the kiln was ignited at the bottom and the fire would spread upward. Typically, it took a day to load, three days to fire, and two days to cool. When thoroughly burned and cooled, the lime was raked out through the “eye.”

Because of the high heating temperature needed kilns were generally of small size, no more than 15 feet in length and width. Any bigger, and the kiln, also made of limestone, could burn or collapse under the intense heat.

An early Kasota Prairie lime kiln was operated by George Clapp. His kiln and quarry were located in Section 17 of Kasota Township. At this location, a layer of fine gray limestone, about two feet thick, presumably made excellent lime. I believe this kiln’s site was near the now-defunct railroad village of Caroline (or Caroline Station). It was developed as a boarding station near where the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad and the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific Railroad crossed. It was also located close to old LeSueur County Highway 5 ( now Hwy 21). Formerly, it was called the Dodd Road. According to Steven Ulmen,[6] a local historian, Caroline was named for the eldest daughter of Conrad Smith who owned the land on which the railroad wanted to build a boarding station for passengers coming from the Dodd Road. Smith agreed to the sale of the land and hence Caroline began. This occurred about 1875. The railroad station had passenger boarding on the main level and a signal tower on the second level. There was also a post office and a few houses, the largest built by Conrad Smith. Smith’s Kasota stone house which still stands originally served as a general store as well. Smith also built a lime kiln nearby adjacent to the railroad tracks.

When the Chicago, Milwaukee Railroad tracks were rerouted sometime after 1875, the town of Caroline all but disappeared. As I said, other than Conrad’s historic Kasota stone house there is nothing to mark the former existence of Caroline; nor are there any remains of the Clapp lime kiln.

Limestone Mining Methods

Today, as in the past, the most demanding task of limestone mining was the cutting and lifting of the blocks of stone out of the ground, then hauling them to the mill. As has been said, it was not just the high quality of the limestone that developed the industry here, but the rock was close to the surface. The so-called “overburden,” i.e. the surface material above the stone, consisted of a thin layer of top soil and under that three or so feet of poor grade limestone. This is the rubble that had to be first removed before striking good quality stone. After crushing the overburden, it was scooped up and hauled away to an abandoned quarry for landfill. In the early days this removal had to be done by hand. Beginning in the 1950s, large shovels and rail cars were used for this purpose, enabling more overburden to be removed in a shorter amount of time with fewer workers. More recently, explosives are used to break up the overburden. Recently, this blasting went terribly wrong. In a mine near the city of Mankato, the explosive charge was so strong that it blew rock debris into houses and yards of a nearby neighborhood. People outdoors or in their homes were startled to hear and see rocks the size of bowling bowls flying through the air. Hopefully, no explosives will be allowed within a certain distance of an urban area in the future.[7]

The first mining step was to drill two to three inch diameter holes at intervals of a foot or so. Steel spikes were then driven into these drill holes to crack the rock. Remember the old song about the steel-drivin’ man, “John Henry.” I think he used a nine pound hammer. Jim Derner, a former employee of the Vetter Corporation, showed me a 40 pound hammer he used when he was driving steel spikes. He talked about the time and effort this work entailed.[8] Years later, a type of large chain saw was used to cut the stone. A mixture of silica sand water was sprayed around the blade. The blocks of stone, roughly 8 x 5 feet, could weigh up to 20 tons each. For scale, Jim Derner, who is over six feet tall, is standing next to one of these blocks ( see Fig. 8 ). Derricks, first of wood and then of steel, and pulleys were used to lift the blocks out of the quarry. I have found only one remaining wooden derrick standing on the Kasota Prairie. I view it as a monument to all the hard labor employed in early mining. There are other wooden derricks that lie crumbled at the remains of many small quarries. They can be spotted by the clumps of trees that grow around them or from the air. In fact, maybe one half of the area of the town of Kasota was quarried but then subsequently filled-in with the overburden from mining.[9]

As more improved means of mining were developed, bigger blocks of limestone could be mined. The steel spikes were replaced by more recent innovations, including a diamond wire saw which allowed the rock to be cut much faster. It was a revolutionary invention in mining. Finally, when cut, the stone block had six sides, two were cut by the saw; two were cut by the drilling holes to cause a weakness for a crack to develop. The top and bottom of the block were natural breaks in the rock formation.

Today, bucket loaders have replaced derricks and pulleys to haul the blocks out of the quarry. They are then marked and ready to be taken for further sizing and cutting at the mill.

Cutting Kasota Stone

At the mill, the rough block of stone is cut to specifications of size. It is first scanned and cuts are made for the requisite sizes. If the diamond saw was an innovation that revolutionized the cutting of limestone, it takes a back seat today to laser technology. A laser is not only a faster way to cut and also carve limestone, it makes much more refined and careful cuts.

Once cut, the veneer or facade of the stone can be of different types. The three most common are: ledge stone, castle stone, and split face. Ledge stone is of low relief and comes in a variety of colors, textures, shapes and thickness. It is an attractive stone that is used for interior walls and chimneys. Because these pieces of stone are smaller than other cuts, they are more expensive to install. Castle stone is characterized by larger more blocky stones cut into rectangles. Because of its larger size, it is used more for exterior surfaces of houses, fences, planters and gates. Split face is a rough cut stone which exposes the interior of the rock and is used for external walls and outdoor fireplaces and chimneys. The Vetter Stone Company office building near the south end of the Kasota Prairie affords an array of interior and exterior stone types.

Carving Kasota Stone

Limestone is a porous rock which makes it possible to carve. In the past, and with certain specialist carvers today, this was accomplished with hand tools.Various size mallets and chisels were used to carve figures on the surface of the stone. It is an art and the carver is a skilled sculptor.A particularly fine example of this stone carving is at the entrance to the Kasota Prairie Conservation Area (see Fig. 9). A French rock artist was hired by the Unimin Corporation some years ago to carve the topographic landscape of the Conservation Area. The work was done with hand tools on a relatively flat, smooth block of Kasota stone, approximately six feet square and a foot thick. It shows the rolling prairie landscape dotted with lakes and stream valleys descending down to the Minnesota River. It, like the Prairie’s Native American petroglyph, has been worn with time. But, it is still a magnificent work of art carved into a magnificent slab of stone. It should be preserved as a representative type of this art work on the local scene. However, as we shall see, laser technology has virtually made the use of hand tools obsolete, except of course, for highly skilled craftspeople.

Vetter Stone

The major company mining Kasota stone on the Prairie today is the Vetter Stone Company. They have not only carried on the work of the Babcock’s, Wilcox, and Breen pioneer miners, but have created a company whose product is sold around the world. Paul Vetter, Sr. worked in the stone quarries for years and eventually transferred the knowledge of the business to his four sons. In 1954, Paul, Sr. along with Paul, Jr., Willard, Walt, and Howard, formed Vetter Stone.Its first office building was a small hunting cabin on the Prairie. It was made out of limestone, of course. Today, the present offices of Vetter Stone are housed in one of the architectural gems of the state and, as I said, is a showcase for the product’s variety of color, texture, quality and design.

Uses

Kasota stone has been used for the Sinai Temple in Chicago; at Target Field in Minneapolis, MN, the baseball park of the Minnesota Twins; the WCCO News Building in downtown Minneapolis; the Mayo Clinic’s Gonda Building in Rochester, Minnesota; the American Indian Museum in Washington,D.C; and the Grand Casino in Larchwood, Iowa to name a few.[10]

A number of years ago, the company was kind enough to give me and my students a tour through its mill. I thought it operated much like an automobile assembly line. Various blocks of stone had been marked as to where they should be cut. As the blocks moved along a conveyor, a series of laser saws cut the stone to the specifications of size and shape that were marked. When completed the stone pieces were then boxed and loaded onto rail cars. At the time we were on our tour, the stone that was being cut was being shipped to a shopping mall complex in Tokyo, Japan. I was shocked. I could not believe that a company on the Kasota Prairie was part of the global economy. I had my geography students map the route of shipment. From Kasota the stone went by train to Seattle, Washington. Here it was loaded onto a container ship to make its long journey across the Pacific Ocean. At the Tokyo Harbor it was unloaded onto trucks, which hauled the stone to the construction site for the new mall. Clearly, this stone, given its considerable weight, had to be of great value in order to pay for its shipping and loading costs. This should not have come as such a shock to me if I had remembered that in 1916, a church was torn down in Kasota so its stone could be sent to Philadelphia for a museum. My guess is that the cost of transporting the stone at that time was the equivalent of today’s route to Tokyo.

The prominence of the Vetter Stone Company is illustrated by its involvement in the local community. When George W. Bush made a presidential campaign trip to Minnesota, he chose the Vetter quarries as the setting for a major campaign stop in southern Minnesota. The main quarry is a large amphitheater-like pit. It provided a natural stage to speak to thousands of people. Because of traffic congestion on the county road leading to the quarry and concerns of safety, security checks were the order of the day. Can you imagine President Bush addressing a crowd of several thousand in a stone quarry? The quarry has also hosted concerts from symphony orchestras to rock bands. Vetter Stone a few years ago constructed the Vetter Amphitheater in nearby Mankato, Minnesota for a concert/speaking venue. It hauled in large blocks of stone for seating, the same dimensions of the blocks ready for shipment to the mill, and built a stage, where programs such as Minnesota Public Radio have aired shows, including the popular “Prairie Home Companion.” Howard Vetter, the long-time President of Vetter Stone, recently passed away. However, the contributions that Vetter Stone has made to the area’s economy in jobs and the beauty of its stone, will certainly continue.

To get a feel for the extensive limestone mining that has taken place here over the years, when you visit the Prairie do a little detective work. Keep a count of the numerous former quarries, now filling up with water, bordered by limestone blocks and debris, within the the shadow of a standing or rotting derrick. I don’t think you will be able to count them all.

- Kasota:A Historical Perspective, Urban and Regional Studies Institute, Mankato State University, Mankato MN, Printed by Robinson Graphics, 1976, p.23. ↵

- "Kasota Bridge over the Minnesota River, St. Peter, Minnesota, 1902 - 1907. Nicollet County Historical Society, Accessed April 23, 2019. https://reflections.mndigital.org/catalog/nico:1141 ↵

- Kasota:A Historical Perspective, p. 23. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Walt Vetter Interview, August, 2011. ↵

- Steven Ulmen Interview, August,2011. ↵

- Mankato Fress Press, Mankato,MN, Oct. 21,v 2017. ↵

- 8. Jim Derner Interview, August, 2011. ↵

- Walt Vetter Interview, August, 2011. ↵

- The Vetter Corporation’s web site provides many examples of buildings utilizing its stone. ↵