6.2 Other Types of Political Participation

Democratic Participation

Political participation is action that influences the distribution of social goods and values (Rosenstone & Hansen, 1993). People can vote for representatives, who make policies that will determine how much they have to pay in taxes and who will benefit from social programs. They can take part in organizations that work to directly influence policies made by government officials. They can communicate their interests, preferences, and needs to government by engaging in public debate (Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995). Such political activities can support government officials, institutions, and policies, or aim to change them.

Far more people participate in politics by voting than by any other means. Yet there are many other ways to take part in politics that involve varying amounts of skill, time, and resources. People can work in an election campaign, contact public officials, circulate a petition, join a political organization, and donate money to a candidate or a cause. Serving on a local governing or school board, volunteering in the community, and running for office are forms of participation that require significant time and energy. Organizing a demonstration, protesting, and even rioting are other forms of participation (Milbrath & Goel, 1977).

People also can take part in support activities, more passive forms of political involvement. They may attend concerts or participate in sporting events associated with causes, such as the “Race for the Cure” for breast cancer. These events are designed to raise money and awareness of societal problems, such as poverty and health care. However, most participants are not activists for these causes. Support activities can lead to active participation, as people learn about issues through these events and decide to become involved.

People also can engage in symbolic participation, routine or habitual acts that show support for the political system. People salute the flag and recite the pledge of allegiance at the beginning of a school day, and they sing the national anthem at sporting events. Symbolic acts are not always supportive of the political system. Some people may refuse to say the pledge of allegiance to express their dissatisfaction with government. Citizens can show their unhappiness with leadership choices by the symbolic act of not voting.

People have many options for engaging in politics. People can act alone by writing letters to members of Congress or staging acts of civil disobedience. Some political activities, such as boycotts and protest movements, involve many people working together to attract the attention of public officials. Increasingly people are participating in politics via the media, especially the Internet.

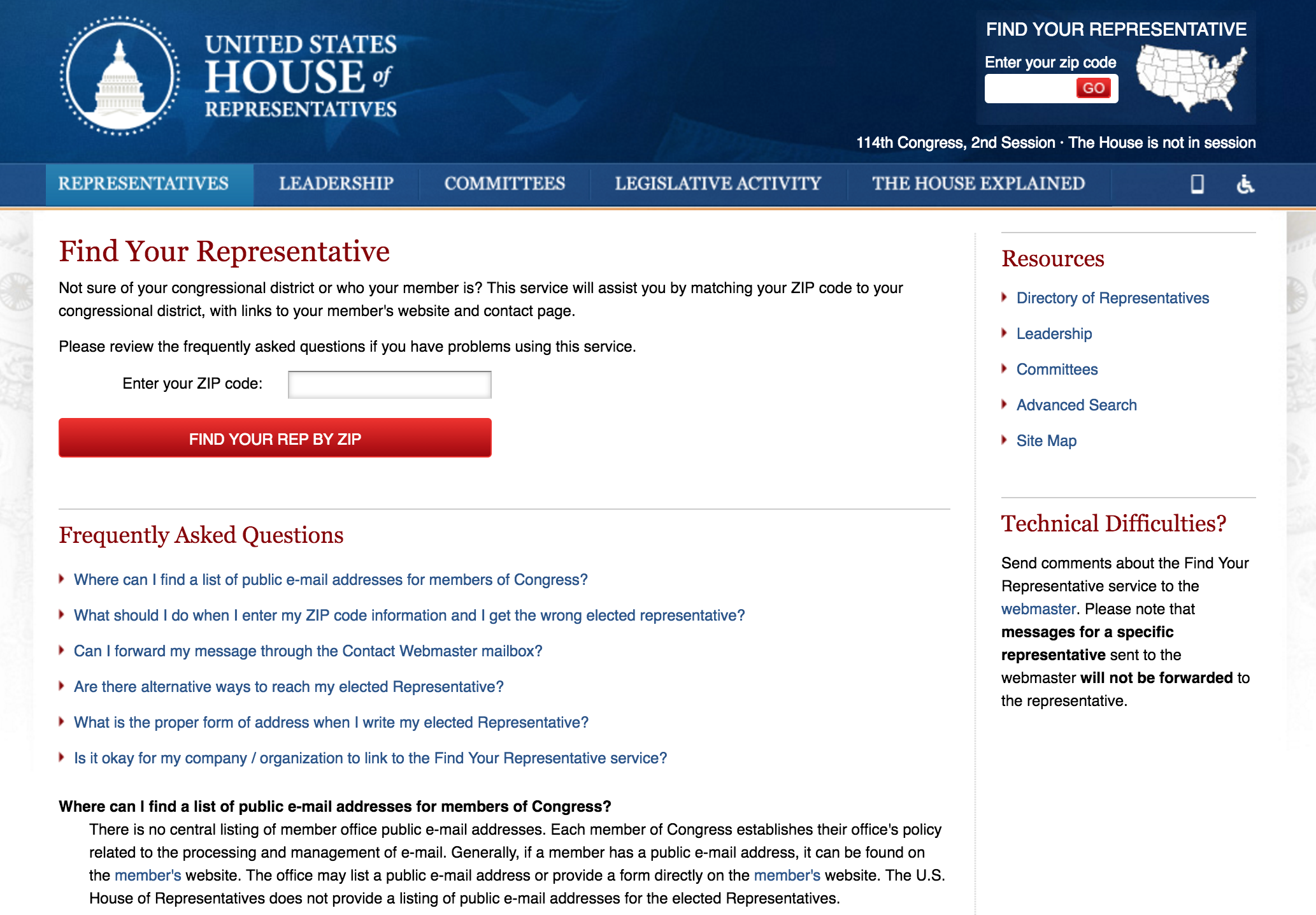

Contacting Public Officials

Expressing opinions about leaders, issues, and policies has become one of the most prominent forms of political participation. The number of people contacting public officials at all levels of government has risen markedly over the past three decades. Seventeen percent of Americans contacted a public official in 1976. By 2008, 44 percent of the public had contacted their member of Congress about an issue or concern (Congressional Management Foundation, 2008). E-mail has made contacting public officials cheaper and easier than the traditional method of mailing a letter.

Students interning for public officials soon learn that answering constituent mail is one of the most time-consuming staff jobs. Every day, millions of people voice their opinions to members of Congress. The Senate alone receives an average of over four million e-mail messages per week and more than two hundred million e-mail messages per year (Congressional Management Foundation, 2008). Still, e-mail may not be the most effective way of getting a message across because office holders believe that an e-mail message takes less time, effort, and thought than a traditional letter. Leaders frequently are “spammed” with mass e-mails that are not from their constituents. Letters and phone calls almost always receive some kind of a response from members of Congress.

Contributing Money

The number of people who give money to a candidate, party, or political organization has increased substantially since the 1960s. Over 25 percent of the public gave money to a cause and 17 percent contributed to a presidential candidate in 2008 (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 2008). Direct mail and e-mail solicitations make fundraising easier, especially when donors can contribute through candidate and political-party websites. A positive side effect of fundraising campaigns is that people are made aware of candidates and issues through appeals for money (Jacobson, 1997).

Americans are more likely to make a financial contribution to a cause or a candidate than to donate their time. As one would expect, those with higher levels of education and income are the most likely to contribute. Those who give money are more likely to gain access to candidates when they are in office.

Campaign Activity

In addition to voting, people engage in a range of activities during campaigns. They work for political parties or candidates, organize campaign events, and discuss issues with family and friends. Generally, about 15 percent of Americans participate in these types of campaign activities in an election year (Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995).

New media offer additional opportunities for people to engage in campaigns. People can blog or participate in discussion groups related to an election. They can create and post videos on behalf of or opposed to candidates. They can use social networking sites, like Facebook, to recruit supporters, enlist volunteers for campaign events, or encourage friends to donate money to a candidate.

Figure 8.5

The 2008 presidential election sparked high levels of public interest and engagement. The race was open, as there was no incumbent candidate, and voters felt they had an opportunity to make a difference. Democrat Barack Obama, the first African American to be nominated by a major party, generated enthusiasm, especially among young people. In addition to traditional forms of campaign activity, like attending campaign rallies and displaying yard signs, the Internet provided a gateway to involvement for 55 percent of Americans (Owen, 2009). Young people, in particular, used social media, like Facebook, to organize online on behalf of candidates. Students advertised campus election events on social media sites, such as candidate rallies and voter registration drives, which drew large crowds.

Running for and Holding Public Office

Being a public official requires a great deal of dedication, time, energy, and money. About 3 percent of the adult population holds an elected or appointed public office (Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995). Although the percentage of people running for and holding public office appears small, there are many opportunities to serve in government.

Potential candidates for public office must gather signatures on a petition before their names can appear on the ballot. Some people may be discouraged from running because the signature requirement seems daunting. For example, running for mayor of New York City requires 7,500 signatures and addresses on a petition. Once a candidate gets on the ballot, she must organize a campaign, solicit volunteers, raise funds, and garner press coverage.

Protest Activity

Protests involve unconventional, and sometimes unlawful, political actions that are undertaken in order to gain rewards from the political and economic system. Protest behavior can take many forms. People can engage in nonviolent acts of civil disobedience where they deliberately break a law that they consider to be unjust (Lipsky, 1968). This tactic was used effectively during the 1960s civil rights movement when African Americans sat in whites-only sections of public busses. Other forms of protest behavior include marking public spaces with graffiti, demonstrating, and boycotting. Extreme forms of protest behavior include acts that cause harm, such as when environmental activists place spikes in trees that can seriously injure loggers, terrorist acts, like bombing a building, and civil war.

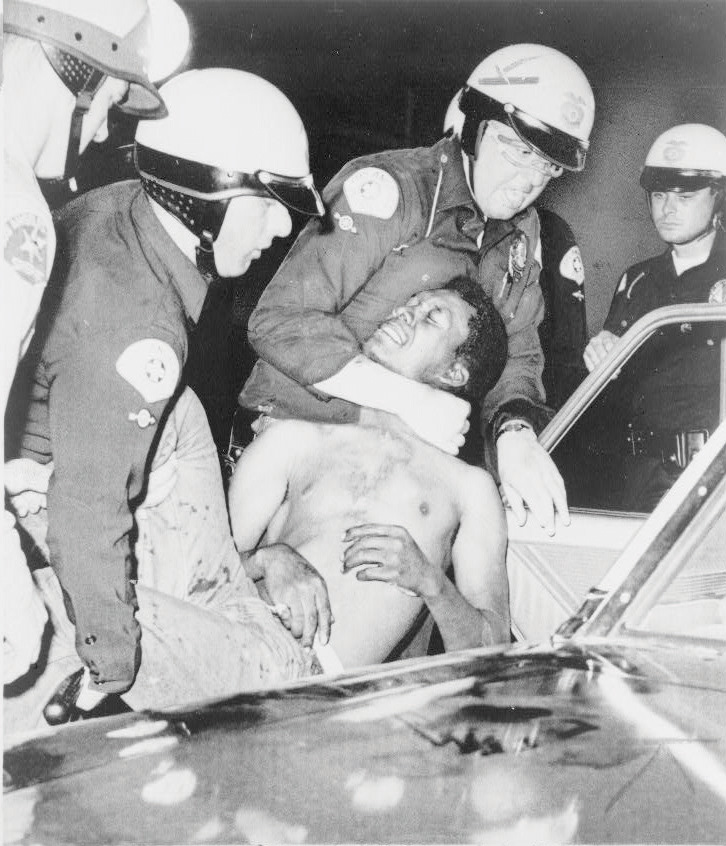

Figure 8.6 The Watts Riots

Extreme discontent with a particular societal condition can lead to rioting. Riots are frequently spontaneous and are sparked by an incident that brings to a head deep-seated frustrations and emotions. Members of social movements may resort to rioting when they perceive that there are no conventional alternatives for getting their message across. Riots can result in destruction of property, looting, physical harm, and even death. Racial tensions sparked by a video of police beating Rodney King in 1991 and the subsequent acquittal of the officers at trial resulted in the worst riots ever experienced in Los Angeles.

College students in the 1960s used demonstrations to voice their opposition to the Vietnam War. Today, students demonstrate to draw attention to causes. They make use of new communications technologies to organize protests by forming groups on the Internet. Online strategies have been used to organize demonstrations against the globalization policies of the World Trade Organization and the World Bank. Over two hundred websites were established to rally support for protests in Seattle, Washington; Washington, DC; Quebec City, Canada; and other locations. Protest participants received online instructions at the protest site about travel and housing, where to assemble, and how to behave if arrested. Extensive e-mail listservs keep protestors and sympathizers in contact between demonstrations. Twitter, a social messaging platform that allows people to provide short updates in real time, has been used to convey eyewitness reports of protests worldwide. Americans followed the riots surrounding the contested presidential election in Iran in 2009 on Twitter, as observers posted unfiltered, graphic details as the violent event unfolded.

Participation in Groups

About half the population takes part in national and community political affairs by joining an interest group, issue-based organization, civic organization, or political party. Organizations with the goal of promoting civic action on behalf of particular causes, or single-issue groups, have proliferated. These groups are as diverse as the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), which supports animal rights, the Concord Coalition, which seeks to protect Social Security benefits, and the Aryan Nation, which promotes white supremacy.

There are many ways to advocate for a cause. Members may engage in lobbying efforts and take part in demonstrations to publicize their concerns. They can post their views on blogs and energize their supporters using Facebook groups that provide information about how to get involved. Up to 70 percent of members of single-issue groups show their support solely by making monetary contributions (Putnam, 2000).

Volunteering

Even activities that on the surface do not seem to have much to do with politics can be a form of political participation. Many people take part in neighborhood, school, and religious associations. They act to benefit their communities without monetary compensation.

Maybe you coach a little league team, visit seniors at a nursing home, or work at a homeless shelter. If so, you are taking part in civil society, the community of individuals who volunteer and work cooperatively outside of formal governmental institutions (Eberly, 1998). Civil society depends on social networks, based on trust and goodwill, that form between friends and associates and allow them to work together to achieve common goals. Community activism is thriving among young people who realize the importance of service that directly assists others. Almost 70 percent of high school students and young adults aged eighteen to thirty report that they have been involved in community activities (Peter D. Hart Research Associates, 1998).

Key Takeaways

There are many different ways that Americans can participate in politics, including voting, joining political parties, volunteering, contacting public officials, contributing money, working in campaigns, holding public office, protesting, and rioting. Voting is the most prevalent form of political participation, although many eligible voters do not turn out in elections. People can take part in social movements in which large groups of individuals with shared goals work together to influence government policies. New media provide novel opportunities for political participation, such as using Facebook to campaign for a candidate and Twitter to keep people abreast of a protest movement.

Exercises

- What are some of the ways you have participated in politics? What motivated you to get involved?

- What political causes do you care the most about? What do you think is the best way for you to advance those causes?

- Do you think people who have committed serious crimes should be allowed to vote? How do you think not letting them vote might affect what kind of policy is made?