2.2 The First American Political System

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What was the Stamp Act Congress?

- What was the Continental Congress?

- What are the principles contained in the Declaration of Independence?

- What were the Articles of Confederation?

We can understand what the Constitution was designed to accomplish by looking at the political system it replaced: the Articles of Confederation, the United States’ first written constitution, which embodied political ideals expressed by the Declaration of Independence.

From Thirteen Colonies to United States

By 1776, the American colonists been living under the rule of the British government for more than a century, and England had long treated the thirteen colonies with a degree of benign neglect. Each colony had established its own legislature. Taxes imposed by England were low, and property ownership was more widespread than in England. People readily proclaimed their loyalty to the king. For the most part, American colonists were proud to be British citizens and had no desire to form an independent nation.

All this began to change in 1763 when the Seven Years War between Great Britain and France came to an end, and Great Britain gained control of most of the French territory in North America. The colonists had fought on behalf of Britain, and many colonists expected that after the war they would be allowed to settle on land west of the Appalachian Mountains that had been taken from France. However, their hopes were not realized. Hoping to prevent conflict with Indian tribes in the Ohio Valley, Parliament passed the Proclamation of 1763, which forbade the colonists to purchase land or settle west of the Appalachian Mountains.[2]

To pay its debts from the war and maintain the troops it left behind to protect the colonies, the British government had to take new measures to raise revenue. Among the acts passed by Parliament were laws requiring American colonists to pay British merchants with gold and silver instead of paper currency and a mandate that suspected smugglers be tried in vice-admiralty courts, without jury trials. What angered the colonists most of all, however, was the imposition of direct taxes: taxes imposed on individuals instead of on transactions.

Because the colonists had not consented to direct taxation, their primary objection was that it reduced their status as free men. The right of the people or their representatives to consent to taxation was enshrined in both Magna Carta and the English Bill of Rights. Taxes were imposed by the House of Commons, one of the two houses of the British Parliament. The North American colonists, however, were not allowed to elect representatives to that body. In their eyes, taxation by representatives they had not voted for was a denial of their rights. Members of the House of Commons and people living in England had difficulty understanding this argument. All British subjects had to obey the laws passed by Parliament, including the requirement to pay taxes. Those who were not allowed to vote, such as women and blacks, were considered to have virtual representation in the British legislature; representatives elected by those who could vote made laws on behalf of those who could not. Many colonists, however, maintained that anything except direct representation was a violation of their rights as English subjects.

By the mid-eighteenth century, Britain’s thirteen colonies on North America’s east coast stretched from Georgia to New Hampshire. Each colony had a governor appointed by the king and a legislature elected by landholding voters. These colonial assemblies, standing for the colonialists’ right of self-government, clashed with the royal governors over issues of power and policies. Each colony, and the newspapers published therein, dealt with the colonial power in London and largely ignored other colonies.

The Stamp Act and Townshend Acts

The first ever direct internal taxes in North America was the Stamp Act (passed in 1765), required the use of paper embossed with the royal seal to prove that taxes had been paid.

Such taxes on commerce alienated powerful interests, including well-off traders in the North and prosperous planters in the South, who complained that the tax was enacted in England without the colonists’ input. Their slogan, “No taxation without representation,” shows a dual concern with political ideals and material self-interest that persisted through the adoption of the Constitution.

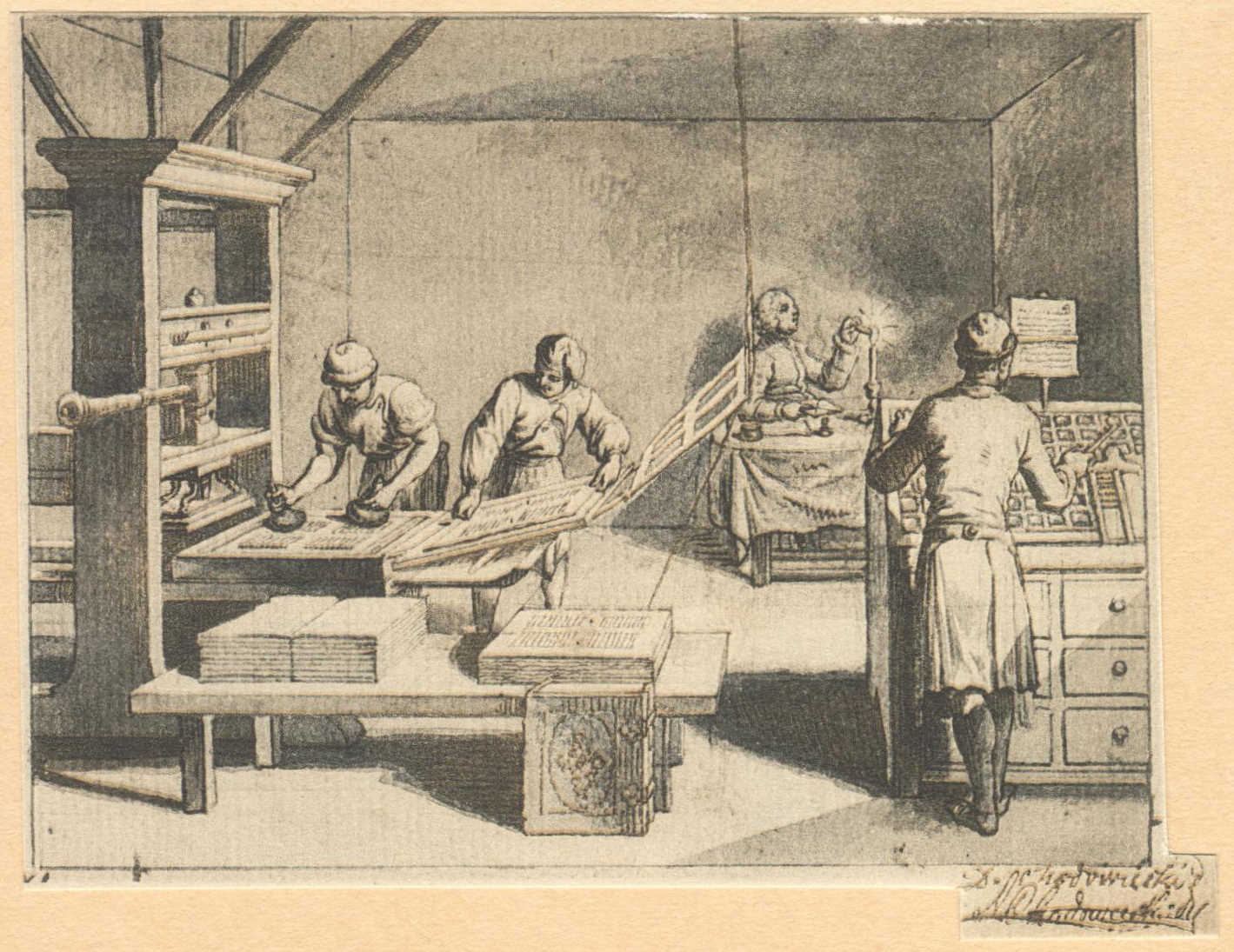

Among the opponents of the Stamp Act were printers who produced newspapers and pamphlets. Newspapers reached large audiences by being passed around—“circulated”—or by being read aloud at taverns (Leonard, 1995). Printers’ precarious financial condition made them dependent on commissions from wealthy people and official subsidies from government, and thus they were eager to please people in power. Crusading journalism against government authorities was rare (Cook, 1998). The Stamp Act, however, was opposed by powerful interests and placed financial burdens on printers, so it was easy for newspaper printers to oppose it vigorously with hostile stories.

During the Stamp Act crisis, news began to focus on events throughout the thirteen colonies. Benjamin Franklin, postmaster of the British government for the colonies, developed a system of post roads linking the colonies. Printers now could send newspapers to each other free of charge in the mail, providing content for each other to copy. Colonial legislatures proposed a meeting of delegates from across the colonies to address their grievances. This gathering, the Stamp Act Congress, met for two weeks in 1765. Delegates sent a petition to the king that convinced British authorities to annul the taxes.

Even though the colonists were successful in having the Stamp Act repealed, it was soon replaced by the Townshend Acts (1767), which imposed taxes on many everyday objects such as glass, tea, and paint. The taxes imposed by the Townshend Acts were as poorly received by the colonists as the Stamp Act had been. The Massachusetts legislature sent a petition to the king asking for relief from the taxes and requested that other colonies join in a boycott of British manufactured goods. British officials threatened to suspend the legislatures of colonies that engaged in a boycott and, in response to a request for help from Boston’s customs collector, sent a warship to the city in 1768. A few months later, British troops arrived, and on the evening of March 5, 1770, an altercation erupted outside the customs house. Shots rang out as the soldiers fired into the crowd. Several people were hit; three died immediately. Britain had taxed the colonists without their consent. Now, British soldiers had taken colonists’ lives.

Following this event, later known as the Boston Massacre, resistance to British rule grew, especially in the colony of Massachusetts. In December 1773, a group of Boston men boarded a ship in Boston harbor and threw its cargo of tea, owned by the British East India Company, into the water to protest British policies, including the granting of a monopoly on tea to the British East India Company, which many colonial merchants resented.[3] This act of defiance became known as the Boston Tea Party.

The Continental Congress

In the early months of 1774, Parliament responded to this latest act of colonial defiance by passing a series of laws called the Coercive Acts, intended to punish Boston for leading resistance to British rule and to restore order in the colonies. These acts virtually abolished town meetings in Massachusetts and otherwise interfered with the colony’s ability to govern itself. This assault on Massachusetts and its economy enraged people throughout the colonies, and delegates from all the colonies except Georgia formed the First Continental Congress to create a unified opposition to Great Britain. Among other things, members of the institution developed a declaration of rights and grievances.

In May 1775, delegates met again in the Second Continental Congress. By this time, war with Great Britain had already begun, following skirmishes between colonial militiamen and British troops at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. Congress drafted a Declaration of Causes explaining the colonies’ reasons for rebellion.

The Declaration of Independence

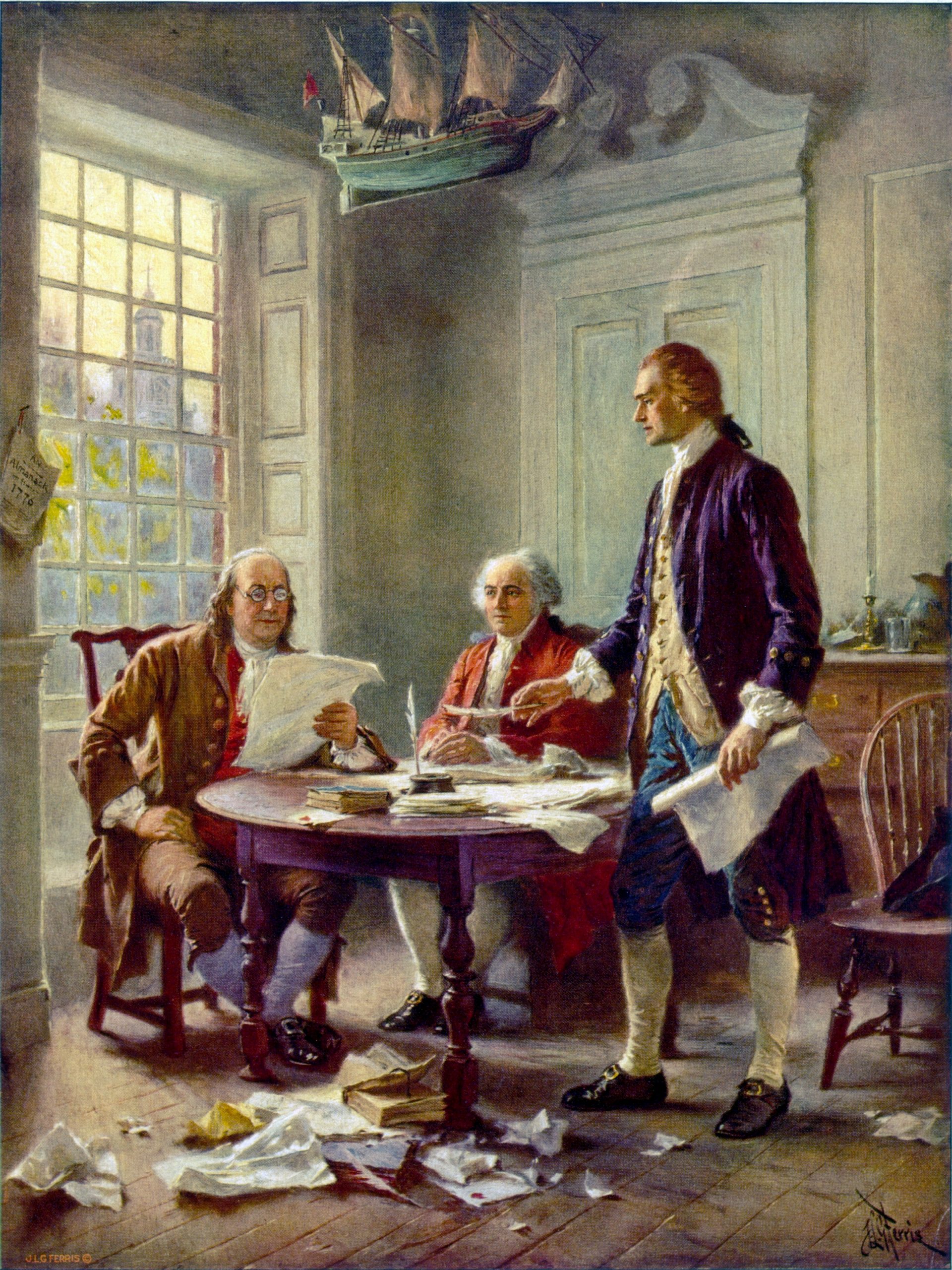

Drafted by Thomas Jefferson, the officially proclaimed the colonies’ separation from Britain. In it, Jefferson eloquently laid out the reasons for rebellion. God, he wrote, had given everyone the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. People had created governments to protect these rights and consented to be governed by them so long as government functioned as intended. However, “whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.” Britain had deprived the colonists of their rights. The king had “establish[ed] . . . an absolute Tyranny over these States.” Just as their English forebears had removed King James II from the throne in 1689, the colonists now wished to establish a new rule.

Jefferson then proceeded to list the many ways in which the British monarch had abused his power and failed in his duties to his subjects. The king, Jefferson charged, had taxed the colonists without the consent of their elected representatives, interfered with their trade, denied them the right to trial by jury, and deprived them of their right to self-government. Such intrusions on their rights could not be tolerated. With their signing of the Declaration of Independence, the founders of the United States committed themselves to the creation of a new kind of government.

The Declaration is also a deeply democratic document (Lynd, 1969; Wills, 1979; Maier, 1997). It is democratic in what it did—asserting the right of the people in American colonies to separate from Britain. And it is democratic in what it said: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal” and have inviolable rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Indeed, it assumes that the people are the best judges of the quality of government and can act wisely on their own behalf.

The Articles of Confederation

Waging a successful war against Great Britain required that the individual colonies, now sovereign states that often distrusted one another, form a unified nation with a central government capable of directing the country’s defense. Gaining recognition and aid from foreign nations would also be easier if the new United States had a national government able to borrow money and negotiate treaties. Accordingly, the Second Continental Congress called upon its delegates to create a new government strong enough to win the country’s independence but not so powerful that it would deprive people of the very liberties for which they were fighting.

Drafted in 1777, the Articles of Confederation were the first political constitution for the government of the United States. They codified the Continental Congress’s practices and powers. The United States of America was a confederation of states. Although the confederation was superior to the individual states, it had no powers without their consent.

Under the Articles, the Continental Congress took over the king’s powers to make war and peace, send and receive ambassadors, enter into treaties and alliances, coin money, regulate Indian affairs, and run a post office. But the confederation could not raise taxes and relied on revenues from each of the states. There was no president to enforce the laws and no judiciary to hear disputes between and among the states. Each state delegation cast a single vote in the Continental Congress. Nine states were needed to enact legislation, so few laws were passed. States usually refused to fund policies that hampered their own interests (Dougherty, 2001). Changes in the Articles required an all-but-impossible unanimous vote of all thirteen delegations. The weakness of the Articles was no accident. The fights with Britain created widespread distrust of central authority. By restricting the national government, Americans could rule themselves in towns and states. Like many political thinkers dating back to ancient Greece, they assumed that self-government worked best in small, face-to-face communities.

| Problems with the Articles of Confederation | |

|---|---|

| Weakness of the Articles of Confederation | Why Was This a Problem? |

| The national government could not impose taxes on citizens. It could only request money from the states. | Requests for money were usually not honored. As a result, the national government did not have money to pay for national defense or fulfill its other responsibilities. |

| The national government could not regulate foreign trade or interstate commerce. | The government could not prevent foreign countries from hurting American competitors by shipping inexpensive products to the United States. It could not prevent states from passing laws that interfered with domestic trade. |

| The national government could not raise an army. It had to request the states to send men. | State governments could choose not to honor Congress’s request for troops. This would make it hard to defend the nation. |

| Each state had only one vote in Congress regardless of its size. | Populous states were less well represented. |

| The Articles could not be changed without a unanimous vote to do so. | Problems with the Articles could not be easily fixed. |

| There was no national judicial system. | Judiciaries are important enforcers of national government power. |

The Articles could not address serious foreign threats. In the late 1780s, Britain denied American ships access to British ports in a trade war. Spain threatened to close the Mississippi River to American vessels. Pirates in the Mediterranean captured American ships and sailors and demanded ransom. The national government had few tools to carry out its assigned task of foreign policy (Rakove, 1996; Edling, 2004).

There was domestic ferment as well. Millions of dollars in paper money issued by state governments to fund the Revolutionary War lost their value after the war (Wood, 1987). Financial interests were unable to collect on debts they were owed. They appealed to state governments, where they faced resistance and even brief armed rebellions.

Newspapers played up Shays’s Rebellion, an armed insurrection by debt-ridden farmers to prevent county courts from foreclosing mortgages on their farms (Richards, 2002). Led by Captain Daniel Shays, it began in 1786, culminated with a march on the federal arsenal in Springfield, Massachusetts, and wound down in 1787. The Continental Congress voted unanimously to raise an army to put down Shays’s Rebellion but could not coax the states to provide the necessary funds. The army was never assembled (Dougherty, 2001). After several months, Massachusetts crushed the uprising with the help of local militias and privately funded armies, but wealthy people were frightened by this display of unrest on the part of poor men and by similar incidents taking place in other states.[3] To find a solution and resolve problems related to commerce, members of Congress called for a revision of the Articles of Confederation. Leaders who supported national government portrayed Shays’s Rebellion as a vivid symbol of state governments running wild and proof of the inability of the Articles of Confederation to protect financial interests. Ordinary Americans, who were experiencing a relatively prosperous time, were less concerned and did not see a need to eliminate the Articles.

Key Takeaways

The first American political system, as expressed in the Articles of Confederation, reflected a distrust of a national government. Its powers were deliberately limited in order to allow Americans to govern themselves in their cities and states.

Exercises

- What was it about the Stamp Act and the decision to award a monopoly on the sale of tea to the East India Company that helped bring the American colonies together? What were the motivations for forming the first Congresses?

- In what way is the Declaration of Independence’s idea that “all men are created equal” a democratic principle? In what sense are people equal if, in practice, they are all different from one another?

- What were the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation? Do you think the American government would be able to function if it were still a confederation? Why or why not?

References

Botein, S., “‘Meer Mechanics’ and an Open Press: The Business and Political Strategies of Colonial American Printers,” Perspectives in American History 9 (1975): 127–225.

Clark, C. E., The Public Prints: The Newspaper in Anglo-American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), chap. 9.

Cook, T. E., Governing with the News: The News Media as a Political Institution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), chap. 2.

Dougherty, K. L., Collective Action under the Articles of Confederation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), chaps. 4–5.

Leonard, T. C., News for All: America’s Coming-of-Age with the Press (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), chap. 1.

Lynd, S., The Intellectual Origins of American Radicalism (New York: Vintage, 1969).

Maier, P., American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York: Knopf, 1997).

Rakove, J. N., The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress (New York: Knopf, 1979).

Wills, G., Inventing America: Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence (New York: Vintage, 1979).

Nathaniel Philbrick. 2006. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War. New York: Penguin, 41. ↵

François Furstenberg. 2008. “The Significance of the Trans-Appalachian Frontier in Atlantic History,” The American Historical Review 113 (3): 654. ↵

Bernhard Knollenberg. 1975. Growth of the American Revolution: 1766-1775. New York: Free Press, 95-96. ↵