2.3 Creating and Ratifying the Constitution

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What was Shays’s Rebellion?

- What was the Constitutional Convention?

- What were the three cross-cutting divides at the Constitutional Convention?

- What were the main compromises at the Constitutional Convention?

- Who were the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists?

- What factors explain ratification of the Constitution?

Calling a Constitutional Convention

The Constitutional Convention was convened in 1787 to propose limited reforms to the Articles of Confederation. Instead, however, the Articles would be replaced by a new, far more powerful national government. Twelve state legislatures sent delegates to Philadelphia (Rhode Island did not attend). Each delegation would cast a single vote.

Who Were the Delegates?

The delegates were not representative of the American people. They were well-educated property owners, many of them wealthy, who came mainly from prosperous seaboard cities, including Boston and New York. Most had served in the Continental Congress and were sensitive to the problems faced by the United States. Few delegates had political careers in the states, and so they were free to break with existing presumptions about how government should be organized in America.

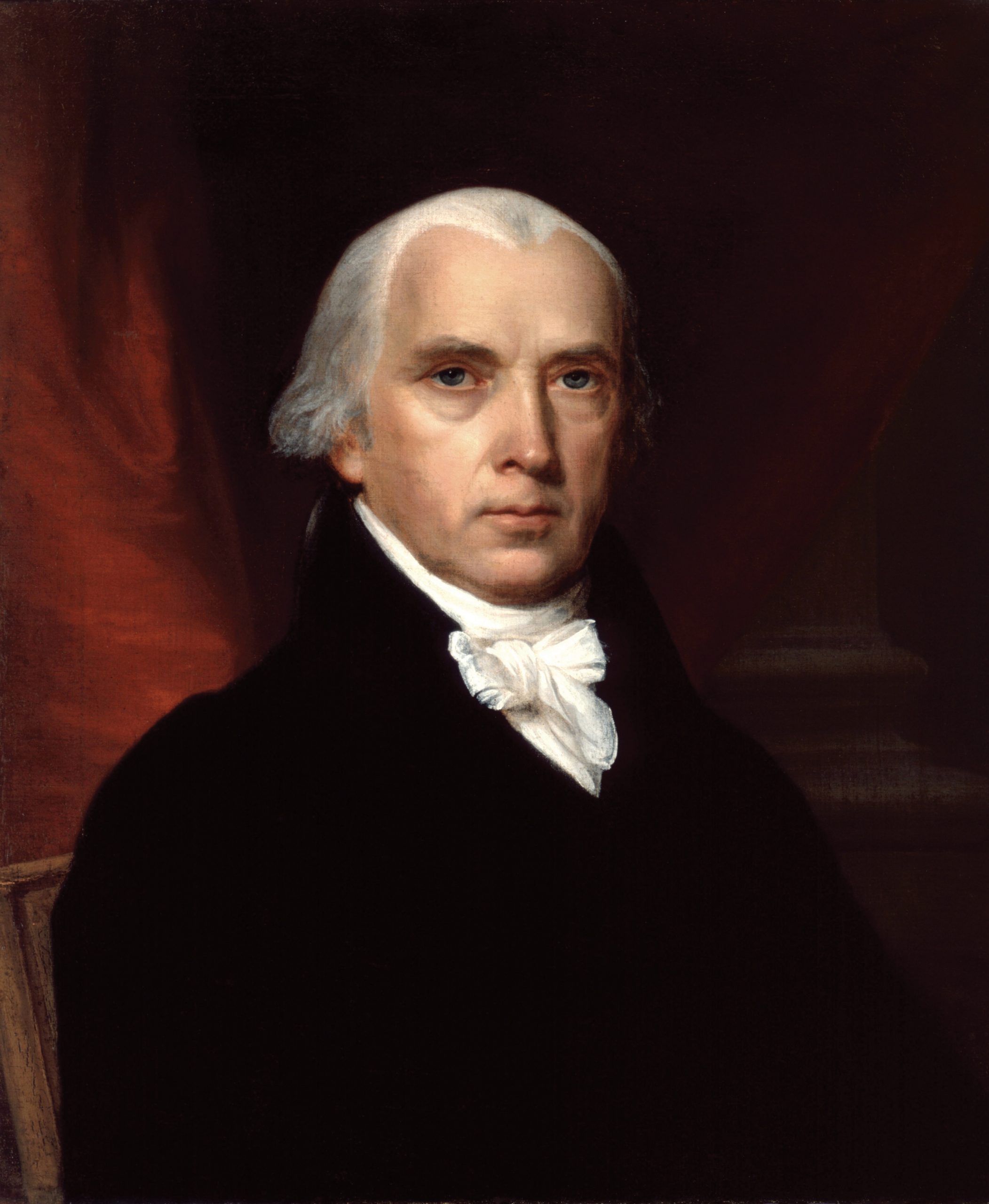

The Constitutional Convention was a mix of great and minor characters. Exalted figures and brilliant intellects sat among nonentities, drunkards, and nincompoops. The convention’s driving force and chief strategist was a young, bookish politician from Virginia named James Madison. He successfully pressured revered figures to attend the convention, such as George Washington, the commanding officer of the victorious American revolutionaries, and Benjamin Franklin, a man at the twilight of a remarkable career as printer, scientist, inventor, postmaster, philosopher, and diplomat.

Fifty-five delegates arrived in Philadelphia in May 1787 for the meeting that became known as the Constitutional Convention. Deliberations took place in secret, as delegates did not want the press and the public to know the details of what they were considering. Newspapers hardly mentioned the convention at all, and when they did, it was in vague references praising the high caliber of the delegates (Alexander, 1990). Many delegates wanted to strengthen the role and authority of the national government but feared creating a central government that was too powerful. They wished to preserve state autonomy, although not to a degree that prevented the states from working together collectively or made them entirely independent of the will of the national government. While seeking to protect the rights of individuals from government abuse, they nevertheless wished to create a society in which concerns for law and order did not give way in the face of demands for individual liberty. They wished to give political rights to all free men but also feared mob rule, which many felt would have been the result of Shays’ Rebellion had it succeeded. Delegates from small states did not want their interests pushed aside by delegations from more populous states like Virginia. And everyone was concerned about slavery. Representatives from southern states worried that delegates from states where it had been or was being abolished might try to outlaw the institution. Those who favored a nation free of the influence of slavery feared that southerners might attempt to make it a permanent part of American society. The only decision that all could agree on was the election of George Washington, the former commander of the Continental Army and hero of the American Revolution, as the president of the convention.

James Madison drafted the first working proposal for a Constitution and took copious notes at the convention. Published after his death in 1836, they are the best historical source of the debates; they reveal the extraordinary political complexity of the deliberations and provide remarkable insight into what the founders had in mind. Once the Constitution was drafted, Madison helped write and publish a series of articles in a New York newspaper. These Federalist papers defend the political system the Constitutional Convention had crafted.

The Question of Representation: Small States vs. Large States

One of the first differences among the delegates to become clear was between those from large states, such as New York and Virginia, and those who represented small states, like Delaware. When discussing the structure of the government under the new constitution, the delegates from Virginia called for a consisting of two houses. The number of a state’s representatives in each house was to be based on the state’s population. In each state, representatives in the lower house would be elected by popular vote. These representatives would then select their state’s representatives in the upper house from among candidates proposed by the state’s legislature. Once a representative’s term in the legislature had ended, the representative could not be reelected until an unspecified amount of time had passed.

Delegates from small states objected to this . Another proposal, the , called for a with one house, in which each state would have one vote. Thus, smaller states would have the same power in the national legislature as larger states. However, the larger states argued that because they had more residents, they should be allotted more legislators to represent their interests.

After debating at length over whether the Virginia Plan or the New Jersey Plan provided the best model for the nation’s legislature, the framers of the Constitution had ultimately arrived at what is called the Connecticut Compromise, or the , suggested by Roger Sherman of Connecticut. Congress, it was decided, would consist of two chambers: the Senate and the House of Representatives. Each state, regardless of size, would have two senators, making for equal representation as in the New Jersey Plan. Representation in the House would be based on population. Senators were to be appointed by state legislatures, a variation on the Virginia Plan. Members of the House of Representatives would be popularly elected by the voters in each state. Elected members of the House would be limited to two years in office before having to seek reelection, and those appointed to the Senate by each state’s political elite would serve a term of six years.

Congress was given great power, including the power to tax, maintain an army and a navy, and regulate trade and commerce. Congress had authority that the national government lacked under the Articles of Confederation. It could also coin and borrow money, grant patents and copyrights, declare war, and establish laws regulating naturalization and bankruptcy. While legislation could be proposed by either chamber of Congress, it had to pass both chambers by a majority vote before being sent to the president to be signed into law, and all bills to raise revenue had to begin in the House of Representatives. Only those men elected by the voters to represent them could impose taxes upon them. There would be no more taxation without representation.

Slavery and Freedom

Another fundamental division separated the states. Following the Revolution, some of the northern states had either abolished slavery or instituted plans by which slaves would gradually be emancipated. Pennsylvania, for example, had passed the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1780. All people born in the state to enslaved mothers after the law’s passage would become indentured servants to be set free at age twenty-eight. In 1783, Massachusetts had freed all enslaved people within the state. Many Americans believed slavery was opposed to the ideals stated in the Declaration of Independence. Others felt it was inconsistent with the teachings of Christianity. Some feared for the safety of the country’s white population if the number of slaves and white Americans’ reliance on them increased. Although some southerners shared similar sentiments, none of the southern states had abolished slavery and none wanted the Constitution to interfere with the institution. In addition to supporting the agriculture of the South, slaves could be taxed as property and counted as population for purposes of a state’s representation in the government.

The Great Compromise that determined the structure of Congress soon led to another debate, however. When states took a census of their population for the purpose of allotting House representatives, should slaves be counted? Southern states were adamant that they should be, while delegates from northern states were vehemently opposed, arguing that representatives from southern states could not represent the interests of enslaved people. If slaves were not counted, however, southern states would have far fewer representatives in the House than northern states did. For example, if South Carolina were allotted representatives based solely on its free population, it would receive only half the number it would have received if slaves, who made up approximately 43 percent of the population, were included.[1]

The resolved the impasse, although not in a manner that truly satisfied anyone. For purposes of Congressional apportionment, slaveholding states were allowed to count all their free population, including free African Americans and 60 percent (three-fifths) of their enslaved population. To mollify the north, the compromise also allowed counting 60 percent of a state’s slave population for federal taxation, although no such taxes were ever collected. Another compromise regarding the institution of slavery granted Congress the right to impose taxes on imports in exchange for a twenty-year prohibition on laws attempting to ban the importation of slaves to the United States, which would hurt the economy of southern states more than that of northern states. Because the southern states, especially South Carolina, had made it clear they would leave the convention if abolition were attempted, no serious effort was made by the framers to abolish slavery in the new nation, even though many delegates disapproved of the institution.

Separation of Powers and Checks and Balances

Although debates over slavery and representation in Congress occupied many at the convention, the chief concern was the challenge of increasing the authority of the national government while ensuring that it did not become too powerful. The framers resolved this problem through a , dividing the national government into three separate branches and assigning different responsibilities to each one. They also created a system of by giving each of three branches of government the power to restrict the actions of the others, thus requiring them to work together.

Congress was given the power to make laws, but the executive branch, consisting of the president and the vice president, and the federal judiciary, notably the Supreme Court, were created to, respectively, enforce laws and try cases arising under federal law. Neither of these branches had existed under the Articles of Confederation. Thus, Congress can pass laws, but its power to do so can be checked by the president, who can potential legislation so that it cannot become a law. Later, in the 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison, the U.S. Supreme Court established its own authority to rule on the constitutionality of laws, a process called judicial review.

Other examples of checks and balances include the ability of Congress to limit the president’s veto. Should the president veto a bill passed by both houses of Congress, the bill is returned to Congress to be voted on again. If the bill passes both the House of Representatives and the Senate with a two-thirds vote in its favor, it becomes law even though the president has refused to sign it.

Congress is also able to limit the president’s power as commander-in-chief of the armed forces by refusing to declare war or provide funds for the military. To date, the Congress has never refused a president’s request for a declaration of war. The president must also seek the advice and consent of the Senate before appointing members of the Supreme Court and ambassadors, and the Senate must approve the ratification of all treaties signed by the president. Congress may even remove the president from office. To do this, both chambers of Congress must work together. The House of Representatives impeaches the president by bringing formal charges against him or her, and the Senate tries the case in a proceeding overseen by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. The president is removed from office if found guilty.

According to political scientist Richard Neustadt, the system of separation of powers and checks and balances does not so much allow one part of government to control another as it encourages the branches to cooperate. Instead of a true separation of powers, the Constitutional Convention “created a government of separated institutions sharing powers.”[4] For example, knowing the president can veto a law he or she disapproves, Congress will attempt to draft a bill that addresses the president’s concerns before sending it to the White House for signing. Similarly, knowing that Congress can override a veto, the president will use this power sparingly.

*Watch this video to learn more about separation of powers and checks and balances.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=0bf3CwYCxXw%3Ffeature%3Doembed%26rel%3D0

Federal Power vs. State Power

The strongest guarantee that the power of the national government would be restricted and the states would retain a degree of sovereignty was the framers’ creation of a federal system of government. In a , power is divided between the federal (or national) government and the state governments. Great or explicit powers, called , were granted to the federal government to declare war, impose taxes, coin and regulate currency, regulate foreign and interstate commerce, raise and maintain an army and a navy, maintain a post office, make treaties with foreign nations and with Native American tribes, and make laws regulating the naturalization of immigrants.

All powers not expressly given to the national government, however, were intended to be exercised by the states. These powers are known as . Thus, states remained free to pass laws regarding such things as intrastate commerce (commerce within the borders of a state) and marriage. Some powers, such as the right to levy taxes, were given to both the state and federal governments. Both the states and the federal government have a chief executive to enforce the laws (a governor and the president, respectively) and a system of courts.

Although the states retained a considerable degree of sovereignty, the in Article VI of the Constitution proclaimed that the Constitution, laws passed by Congress, and treaties made by the federal government were “the supreme Law of the Land.” In the event of a conflict between the states and the national government, the national government would triumph. Furthermore, although the federal government was to be limited to those powers enumerated in the Constitution, Article I provided for the expansion of Congressional powers if needed. The “necessary and proper” clause of Article I provides that Congress may “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing [enumerated] Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.”

The Constitution also gave the federal government control over all “Territory or other Property belonging to the United States.” This would prove problematic when, as the United States expanded westward and population growth led to an increase in the power of the northern states in Congress, the federal government sought to restrict the expansion of slavery into newly acquired territories.

The Executive

By now, the Constitutional Convention could not break down, because the document had something for everybody. Small states liked the security of a national government and their equal representation in the Senate. The Deep South and New England valued the protection of their economic bases. Pennsylvania and Virginia—the two most populous, centrally located states—foresaw a national government that would extend the reach of their commerce and influence.

The convention’s final sticking point was the nature of the executive. The debate focused on how many people would be president, the power of the office, the term of the office, how presidents would be elected, and whether they could serve multiple terms.

To break the logjam on the presidency, the convention created the Electoral College as the method of electing the president, a political solution that gave something to each of the state-based interests. The president would not be elected directly by the popular vote of citizens. Instead, electors chosen by state legislatures would vote for president. Small states got more electoral votes than warranted by population, as the number of electors is equal to the total of representatives and senators. If the Electoral College did not produce a majority result, the president would be chosen by the popularly elected House, but with one vote per state delegation (Roche, 1961). With all sides mollified, the convention agreed that the office of president would be held by one person who could run for multiple terms.

Ratifying the Constitution

The signing of the Constitution by the delegates on September 17, 1787, was just the beginning. The Constitution would go into effect only after being approved by specially elected ratifying conventions in nine states.

Ratification was not easy to win. In most states, property qualifications for voting had broadened from landholding to taxpaying, thereby including most white men, many of whom benefited from the public policies of the states. Popular opinion for and against ratification was evenly split. In key states like Massachusetts and Virginia, observers thought the opposition was ahead (Main, 1961; Fink & Riker, 1989).

The elections to the ratifying conventions revealed that opponents of the Constitution tended to come from rural inland areas (not from cities and especially not from ports, where merchants held sway). They held to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence, which favored a deliberately weak national government to enhance local and state self-government (Storing, 1988). They thought that the national government’s powers, the complex system of government, lengthy terms of office, and often indirect elections in the new Constitution distanced government from the people unacceptably.

Opponents also feared that the strength of the proposed national government posed a threat to individual freedoms. They criticized the Constitution’s lack of a Bill of Rights—clauses to guarantee specific liberties from infringement by the new government. A few delegates to the Constitutional Convention, notably George Mason of Virginia and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, had refused to sign the document in the absence of a Bill of Rights.

Despite such objections and obstacles, the campaign for ratification was successful in all thirteen states (Maier, 2010). The advocates of the national political system, benefiting from the secrecy of the Constitutional Convention, were well prepared to take the initiative. They called themselves not nationalists but Federalists. Opponents to the Constitution were saddled with the name of Anti-Federalists, though they were actually the champions of a federation of independent states.

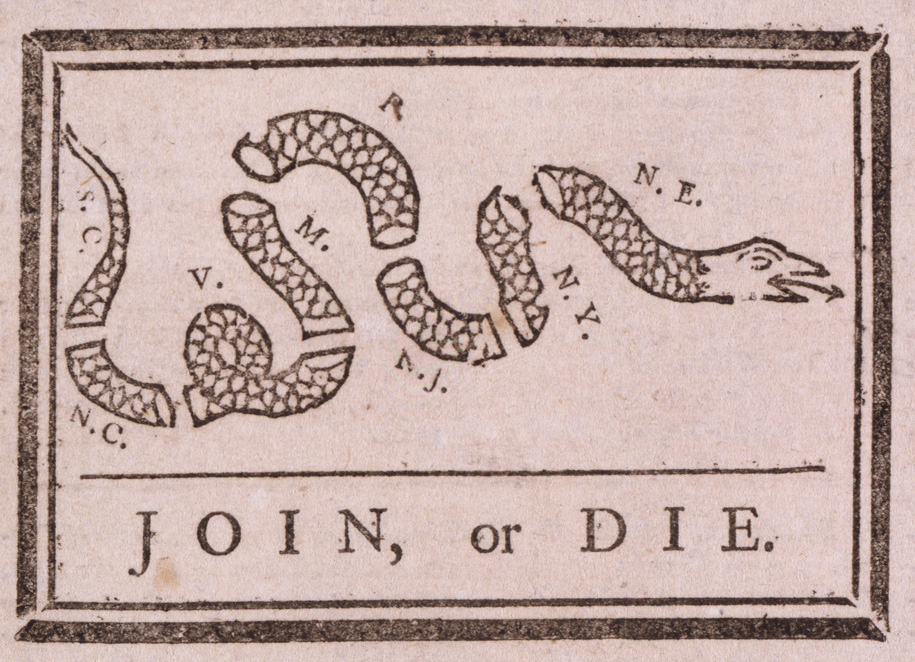

The US newspaper system boosted the Federalist cause. Of the approximately one hundred newspapers being published during the ratification campaign of 1787–88, “not more than a dozen…could be classed as avowedly antifederal” (Rutland, 1966). Anti-Federalist arguments were rarely printed and even less often copied by other newspapers (Riker, 1996). Printers followed the money trail to support the Federalists. Most newspapers, especially those whose stories were reprinted by others, were based in port cities, if only because arriving ships provided good sources of news. Such locales were dominated by merchants who favored a national system to facilitate trade and commerce. Today the most famous part of this newspaper campaign is the series of essays (referred to earlier) written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, and published in New York newspapers under the collective pseudonym “Publius.” The authors used their skills at legal argumentation to make the strongest case they could for the document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention. These Federalist papers, steeped in discussion of political theory and history, offer the fullest logic for the workings of the Constitution.

By asking conventions to ratify the Constitution, the Federalists evaded resistance from state legislatures. Federalists campaigned to elect sympathetic ratifiers and hoped that successive victories, publicized in the press, would build momentum toward winning ratification by all thirteen states. Anti-Federalists did not decry the process by which the Constitution was drafted and ratified. Instead, they participated in the ratification process, hoping to organize a new convention to remedy the Constitution’s flaws.

Not all states were eager to ratify the Constitution, especially since it did not specify what the federal government could not do and did not include a Bill of Rights. Massachusetts narrowly voted in favor of ratification, with the provision that the first Congress take up recommendations for amending the Constitution. New Hampshire, Virginia, and New York followed this same strategy. Once nine states had ratified it, the Constitution was approved. Madison was elected to the first Congress and proposed a Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution. Only after the Congress had approved the Bill of Rights did North Carolina and Rhode Island ratify the Constitution.

Key Takeaways

We have shown that the Constitution was a political document, drafted for political purposes, by skillful politicians who deployed shrewd media strategies. At the Constitutional Convention, they reconciled different ideas and base self-interests. Through savvy compromises, they resolved cross-cutting divisions and achieved agreement on such difficult issues as slavery and electing the executive. In obtaining ratification of the Constitution, they adroitly outmaneuvered or placated their opponents. The eighteenth-century press was crucial to the Constitution’s success by keeping its proceedings secret and supporting ratification.

Exercises

- From what James Madison says in Federalist No. 10, what economic interests was the Constitution designed to protect? Do you agree that the liberty to accumulate wealth is an essential part of liberty?

- What did James Madison mean by “factions,” and what danger did they pose? How did he hope to avoid the problems factions could cause?

- Why were the Constitutional Convention’s deliberations kept secret? Do you think it was a good idea to keep them secret? Why or why not?

- What were the main divisions that cut across the Constitutional Convention? What compromises bridged each of these divisions?

References

Alexander, J. K., The Selling of the Constitutional Convention: A History of News Coverage (Madison, WI: Madison House, 1990).

Beard, C. A., An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (New York: Macmillan, 1913).

Dougherty, K. L., Collective Action under the Articles of Confederation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), chap. 6.

Edling, M. M., A Revolution in Favor of Government: Origins of the U.S. Constitution and the Making of the American State (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Farrand, M., ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1937), vol. 1, 17.

Fink, E. C. and William H. Riker, “The Strategy of Ratification” in The Federalist Papers and the New Institutionalism, ed. Bernard Grofman and Donald Wittman (New York: Agathon Press, 1989), 220–55.

Kaminski, J. P. and Gaspare J. Saladino, eds., Commentaries on the Constitution, Public and Private (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1981), vol. 1, xxxii–xxxix.

Maier, P., Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010).

Main, J. T., The Antifederalists: Critics of the Constitution, 1781–1788 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 249

Rakove, J. N., Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Knopf, 1996), 25–28.

Richards, L. A., Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

Riker, W. H., The Strategy of Rhetoric: Campaigning for the American Constitution (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 26–28.

Robertson, D. B., “Madison’s Opponents and Constitutional Design,” American Political Science Review 99 (2005): 225–44.

Roche, J. P., “The Founding Fathers: A Reform Caucus in Action,” American Political Science Review 55 (December 1961): 810.

Rutland, R. A., “The First Great Newspaper Debate: The Constitutional Crisis of 1787–88,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (1987): 43–58.

Rutland, R. A., The Ordeal of the Constitution: The Antifederalists and the Ratification Struggle of 1787–1788 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 38.

Storing, H., What the Anti-Federalists Were For (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988).

Wood, G. S., “Interests and Disinterestedness in the Making of a Constitution,” in Beyond Confederation: Origins of the Constitution and American National Identity, ed. Richard Beeman, Stephen Botein, and Edward C. Carter II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 69–109.