Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What is federalism?

- What powers does the Constitution grant to the national government?

- What powers does the Constitution grant to state governments?

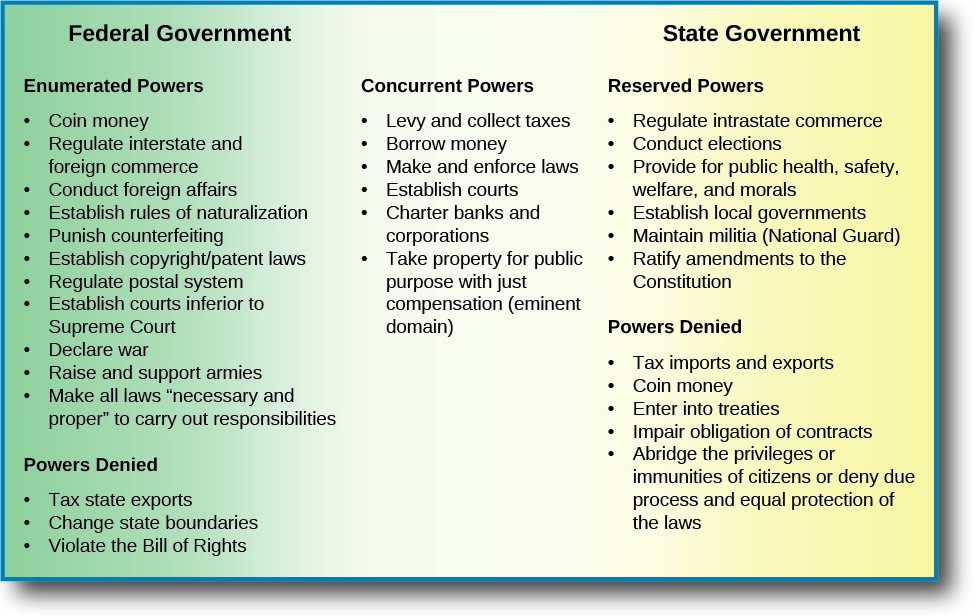

The Constitution and its amendments outline distinct powers and tasks for national and state governments. Some of these constitutional provisions enhance the power of the national government; others boost the power of the states. Checks and balances protect each level of government against encroachment by the others.

National Powers

The Constitution gives the national, or federal, government three types of power. In particular, Article I authorizes Congress to act in certain enumerated domains.

Exclusive Powers

The Constitution gives exclusive powers to the national government that states may not exercise. The expressed powers of the national legislature are enumerated in Article I, Section 8 (threfore these powers are sometimes referred to as enumerated powers). These powers define the jurisdictional boundaries within which the federal government has authority. In seeking not to replay the problems that plagued the young country under the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution’s framers granted Congress specific powers that ensured its authority over national and foreign affairs. To provide for the general welfare of the populace, it can tax, borrow money, regulate interstate and foreign commerce, and protect property rights, for example. To provide for the common defense of the people, the federal government can raise and support armies and declare war. Furthermore, national integration and unity are fostered with the government’s powers over the coining of money, naturalization, postal services, and other responsibilities.

Implied Powers

The Constitution authorizes Congress to enact all laws “necessary and proper” to execute its enumerated powers. The last clause of Article I, Section 8, commonly referred to as the or the necessary and proper cause, enables Congress “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying” out its constitutional responsibilities. While the enumerated powers define the policy areas in which the national government has authority, the elastic clause allows it to create the legal means to fulfill those responsibilities. This necessary and proper clause allows the national government to claim implied powers, logical extensions of the powers explicitly granted to it. For example, national laws can, and do, outlaw discrimination in employment under Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce.

States’ Reserved Powers

The powers of the state governments were never listed in the original Constitution. The consensus among the framers was that states would retain any powers not prohibited by the Constitution or delegated to the national government.[6] However, when it came time to ratify the Constitution, a number of states requested that an amendment be added explicitly identifying the reserved powers of the states. What these Anti-Federalists sought was further assurance that the national government’s capacity to act directly on behalf of the people would be restricted, which the first ten amendments (Bill of Rights) provided. The Tenth Amendment affirms the states’ reserved powers: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” States maintain inherent powers that do not conflict with the Constitution. Notably, in the mid-nineteenth century, the Supreme Court recognized that states could exercise police powers to protect the public’s health, safety, order, and morals (License Cases, 1847).

Some other powers are also reserved to the states, such as ratifying proposed amendments to the Constitution and deciding how to elect Congress and the president. National officials are chosen by state elections. Additionally, Congressional districts are drawn within states. Their boundaries are reset by state officials after the decennial census. So the party that controls a state’s legislature and governorship is able to manipulate districts in its favor.

Concurrent Powers

The Constitution accords some powers to the national government without barring them from the states. These concurrent powers include regulating elections, taxing and borrowing money, and establishing courts.

National and state governments both regulate commercial activity. In its commerce clause, the Constitution gives the national government broad power to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States and with the Indian tribes.” This clause allowed the federal government to establish a national highway system that traverses the states. A state may regulate any and all commerce that is entirely within its borders.

National and state governments alike make and enforce laws and choose their own leaders. They have their own constitutions and court systems. A state’s Supreme Court decision may be appealed to the US Supreme Court provided that it raises a “federal question,” such as an interpretation of the US Constitution or of national law.

National Government’s Responsibilities to the States

The Constitution lists responsibilities the national government has to the states. The Constitution cannot be amended to deny the equal representation of each state in the Senate. A state’s borders cannot be altered without its consent. The national government must guarantee each state “a republican form of government” and defend any state, upon its request, from invasion or domestic upheaval.

States’ Responsibilities to Each Other

Article IV lists responsibilities states have to each other: each state must give “full faith and credit” to acts of other states. For instance, a driver’s license issued by one state must be recognized as legal and binding by another.

No state may deny “privileges and immunities” to citizens of other states by refusing their fundamental rights. States can, however, deny benefits to out-of-staters if they do not involve fundamental rights. Courts have held that a state may require newly arrived residents to live in the state for a year before being eligible for in-state (thus lower) tuition for public universities, but may not force them to wait as long before being able to vote or receive medical care.

Officials of one state must extradite persons upon request to another state where they are suspected of a crime.

States dispute whether and how to meet these responsibilities. Conflicts sometimes are resolved by national authority. In 2003, several states wanted to try John Muhammad, accused of being the sniper who killed people in and around Washington, DC. The US attorney general, John Ashcroft, had to decide which jurisdiction would be first to put him on trial. Ashcroft, a proponent of capital punishment, chose the state with the toughest death-penalty law, Virginia.

“The Supreme Law of the Land” and Its Limits

Article VI’s supremacy clause holds that the Constitution and all national laws are “the supreme law of the land.” State judges and officials pledge to abide by the US Constitution. In any clash between national laws and state laws, the latter must give way. However, as we shall see, boundaries are fuzzy between the powers national and state governments may and may not wield. Implied powers of the national government, and those reserved to the states by the Tenth Amendment, are unclear and contested. The Constitution leaves much about the relative powers of national and state governments to be shaped by day-to-day politics in which both levels have a strong voice.

A Land of Many Governments

“Disliking government, Americans nonetheless seem to like governments, for they have so many of them” (Derthick, 2001).Table 3.1 “Governments in the United States” catalogs the 87,576 distinct governments in the fifty states. They employ over eighteen million full-time workers. These numbers would be higher if we included territories, Native American reservations, and private substitutes for local governments such as gated developments’ community associations.

Table 3.1 Governments in the United States

| National government | 1 |

| States | 50 |

| Counties | 3,034 |

| Townships | 16,504 |

| Municipalities | 19,429 |

| Special districts | 35,052 |

| Independent school districts | 13,506 |

| Total governmental units in the United States | 87,576 |

Source: US Bureau of the Census, categorizing those entities that are organized, usually chosen by election, with a governmental character and substantial autonomy.

States

In one sense, all fifty states are equal: each has two votes in the US Senate. The states also have similar governmental structures to the national government: three branches—executive, legislative, and judicial (only Nebraska has a one chamber—unicameral—legislature). Otherwise, the states differ from each other in numerous ways. These include size, diversity of inhabitants, economic development, and levels of education. Differences in population are politically important as they are the basis of each state’s number of seats in the House of Representatives, over and above the minimum of one seat per state.

States get less attention in the news than national and local governments. Many state events interest national news organizations only if they reflect national trends, such as a story about states passing laws regulating or restricting abortions (Leland, 2010).

A study of Philadelphia local television news in the early 1990s found that only 10 percent of the news time concerned state occurrences, well behind the 18 percent accorded to suburbs, 21 percent to the region, and 37 percent to the central city (Kaniss, 1991). Since then, the commitment of local news outlets to state news has waned further. A survey of state capitol news coverage in 2002 revealed that thirty-one state capitols had fewer newspaper reporters than in 2000 (Layton & Dorroh, 2002).

Native American Reservations

In principle, Native American tribes enjoy more independence than states but less than foreign countries. Yet the Supreme Court, in 1831, rejected the Cherokee tribe’s claim that it had the right as a foreign country to sue the state of Georgia. The justices said that the tribe was a “domestic dependent nation” (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 1831). As wards of the national government, the Cherokee were forcibly removed from land east of the Mississippi in ensuing years.

Native Americans have slowly gained self-government. Starting in the 1850s, presidents’ executive orders set aside public lands for reservations directly administered by the national Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). During World War II, Native Americans working for the BIA organized to gain legal autonomy for tribes. Buttressed by Supreme Court decisions recognizing tribal rights, national policy now encourages Native American nations on reservations to draft constitutions and elect governments (Wilkinson, 1987; Castile, 1998; Philip, 1999).

Figure 3.1 Foxwoods Advertisement

The image of glamour and prosperity at casinos operated at American Indian reservations, such as Foxwoods (the largest such casino) in Connecticut, is a stark contrast with the hard life and poverty of most reservations.

Ted Murphy – Hard Rock Casino – CC BY 2.0.

Since the Constitution gives Congress and the national government exclusive “power to regulate commerce…with the Indian tribes,” states have no automatic authority over tribe members on reservations within state borders (Worcester v. Georgia, 1832). As a result, many Native American tribes have built profitable casinos on reservations within states that otherwise restrict most gambling (Montana v. Blackfeet Tribe of Indians, 1985; California v. Cabazon Band of Indians, 1987; Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 1996).

Local Governments

All but two states are divided into administrative units known as counties.[1] States also contain municipalities, whether huge cities or tiny hamlets. They differ from counties by being established by local residents, but their powers are determined by the state. Cutting across these borders are thousands of school districts as well as special districts for drainage and flood control, soil and water conservation, libraries, parks and recreation, housing and community development, sewerage, water supply, cemeteries, and fire protection.[2]

Key Takeaways

Federalism is the American political system’s arrangement of powers and responsibilities among—and ensuing relations between—national, state, and local governments. The US Constitution specifies exclusive and concurrent powers for the national and state governments. Other powers are implied and determined by day-to-day politics.

Exercises

- Consider the different powers that the Constitution grants exclusively to the national government. Explain why it might make sense to reserve each of those powers for the national government.

- Consider the different powers that the Constitution grants exclusively to the states. Explain why it might make sense to reserve each of those powers to the states.

- In your opinion, what is the value of the “necessary and proper” clause? Why might it be difficult to enumerate all the powers of the national government in advance?

References

California v. Cabazon Band of Indians, 480 US 202 (1987)

Castile, G. P., To Show Heart: Native American Self-Determination and Federal Indian Policy, 1960–1975 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1998)

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 US 1 (1831).

Derthick, M., Keeping the Compound Republic: Essays on American Federalism (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2001), 83.

Kaniss, P., Making Local News (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), table 4.4.

Layton, C. and Jennifer Dorroh, “Sad State,” American Journalism Review, June 2002, http://www.ajr.org/article_printable.asp?id=2562.

Leland, J., “Abortion Foes Advance Cause at State Level,” New York Times, June 3, 2010, A1, 16.

License Cases, 5 How. 504 (1847).

Montana v. Blackfeet Tribe of Indians, 471 US 759 (1985)

Philp, K. R., Termination Revisited: American Indians on the Trail to Self-Determination, 1933–1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 US 44 (1996).

Wilkinson, C. F., American Indians, Time, and the Law: Native Societies in a Modern Constitutional Democracy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987).

Worcester v. Georgia, 31 US 515 (1832).

- The two exceptions are Alaska, which has boroughs that do not cover the entire area of the state, and Louisiana, where the equivalents of counties are parishes. ↵

- The US Bureau of the Census categorizes those entities that are organized (usually chosen by election) with a governmental character and substantial autonomy. US Census Bureau, Government Organization: 2002 Census of Governments 1, no. 1: 6, http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/gc021x1.pdf. ↵