Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How do government agencies exercise power through rulemaking, implementation, and adjudication?

- What role does standard operating procedure play in agency accountability?

- How do agencies and the president influence each other?

- How do agencies and Congress influence each other?

13.5 Policymaking for the Bureaucracy and Presidential Legacy

The federal bureaucracy consists of all the agencies under the supervision of the executive branch, headed by the President. But these agencies often act independently to make policy and exert power: legislating by rulemaking; executing by implementation; and adjudicating by hearing complaints, prosecuting cases, and judging disputes.

Rulemaking

Congresses and presidents often enact laws setting forth broad goals with little idea of how to get there. They get publicity in the media and take credit for addressing a problem—and pass tough questions on how to solve the problem to the bureaucracy. Through the process of rulemaking agencies issue statements that implement, interpret, and prescribe policy in an area authorized by legislation passed by Congress, or issued by executive order of the President. These statements seek to clarify current and future policy in an area authorized by the law. For example, the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1971 sought “to assure so far as possible every working man and woman in the Nation safe and healthy work conditions.” Congress created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and directed it to “establish regulations suitable and necessary for carrying this law into effect, which regulations shall be binding.” Since then, OSHA has created many rules regulating everything from handling hazardous chemicals, to use of ladders, and installing non-slick flooring (and many more).

Congress requires agencies to follow prescribed detailed procedures in issuing a rule. The explosion of New Deal agencies in the 1930s created inconsistency from one agency to the next. In 1934, the Federal Register, which prints all rules and decisions made by agencies, was launched to provide a common source. Any rule listed in the Federal Register has the status and force of law. To create a rule, the agency interprets the statute to be applied and lists grounds for a preliminary decision. Next, it invites feedback: holding hearings or eliciting written comments from the public, Congress, and elsewhere in the executive branch. Then it issues a final rule, after which litigation can ensue; the rule may be annulled if courts conclude that the agency did not adequately justify it.

Implementing Policy

The bureaucracy makes policy through rulemaking, it enforces policy through implementation: the process of applying general policies to specific cases in order to put legislation or rules into effect., or applying general policies to given cases. Agencies transform abstract legal language into specific plans and organizational structures. There are rarely simple tests to assess how faithfully they do this. So even the lowliest bureaucrat wields power through implementation.

Some implementation can be easily measured. Examples are the Postal Service’s balance sheet of income and expenditures or the average number of days it takes to deliver a first-class letter over a certain distance in the United States. But an agency’s goals often conflict. Congress and presidents want the Postal Service to balance its budget but also to deliver mail expeditiously and at low cost to the sender and to provide many politically popular but costly services—such as Saturday delivery, keeping post offices open at rural hamlets, and adopting low postal rates for sending newspapers and magazines (Tierney, 1988).

Ambiguous goals also pose problems for agencies. When the Social Security Administration (SSA) was formed in the 1930s, it set up an efficient way to devise standards of eligibility (such as age and length of employment) for retirement benefits. In the 1970s, Congress gave the SSA the task of determining eligibility for supplementary security income and disability insurance. Figuring out who was disabled enough to qualify was far more complex than determining criteria of eligibility for retirement. Enmeshed in controversy, the SSA lost public support (Wilson, 1989; Derthick, 1990).

Adjudicating Disputes

Agencies act like courts through administrative adjudication: applying rules and precedents to individual cases in an adversarial setting with a defense and prosecution. Some, like the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), act as both prosecutor and judge (Gould IV, 1986). Federal law directs workers complaining about unfair labor practices to go to regional directors of NLRB, who decide if there is probable cause that the law has been violated. If so, NLRB’s general counsel brings a case on behalf of the complainant before NLRB’s special administrative law judges, who hear both sides of the dispute and issue a decision. That ruling may be appealed to the full NLRB. Only then may the case go to federal court.

Standard Operating Procedures

How can civil servants prove they are doing their jobs? On a day-to-day basis, it is hard to show that vague policy goals are being met. Instead, they demonstrate that the agency is following agreed-on routines for processing cases—standard operating procedures (SOPs): recurring routines to manage particular cases. (Lindblom, 1959). So it is hard for agencies to “think outside the box”: to step back and examine what they are doing, and why. Sometimes, only severe crises jar agencies out of their inertia. For example, following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) moved to revive old-fashioned forms of human intelligence, such as planting spies in terrorist camps and increasing its number of Arabic-language speakers, when it became clear that its standard operating procedure of using high-tech forms of intelligence, such as satellite images and electronic eavesdropping, had been inadequate to forecast, let alone prevent, the attacks.

How Presidents Influence the Federal Bureaucracy

Agencies are part of the executive branch. Presidents select heads of agencies and make numerous other political appointees to direct and control them. But political appointees have short careers in their offices; they average just over two years (Aberbach & Rockman, 2000). Civil servants’ long careers in government in a single agency can easily outlast any political appointee who spars with them (Aberbach & Rockman, 2000).

Presidents can set up an agency by executive order—and dare Congress not to authorize and fund it. President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order to launch the Peace Corps after Congress did not act on his legislative request. Only then did Congress authorize, and allocate money for, the new venture. Agencies created by presidents are smaller than those begun by Congress; but presidents have more control of their structure and personnel (Howell & Lewis, 2002).

Presidents make strategic appointments. Agency personnel are open to change when new appointees take office. Presidents can appoint true-believer ideologues to the cabinet who become prominent in the news, stand firm against the sway of the civil service, and deflect criticism away from the president. Presidents also can and do fire agency officials who question the White House line. Presidents who dislike an agency’s programs can decide not to replace departing staffers.

How Agencies Influence Presidents

Presidential appointments, especially of cabinet secretaries, are one way to control the bureaucracy. But cabinet secretaries have multiple loyalties. The Senate’s power to confirm nominees means that appointees answer to Congress as well as the president. In office, each secretary is not based at the White House but at a particular agency “amid a framework of established relations, of goals already fixed, of forces long set in motion [in] an impersonal bureaucratic structure resistant to change” (Fenno, Jr., 1959). Surrounded by civil servants who justify and defend department policies, cabinet secretaries are inclined to advocate the departments’ programs rather than presidential initiatives. Some cabinet secretaries value their independence and individuality above the president’s agenda.

With the executive branch’s increasing layers, civil servants often shape outcomes as much as presidents and cabinet secretaries. The decisions they make may or may not be in line with their superiors’ intentions. Or they may structure information to limit the decisions of those above them, changing ambiguous shades of gray to more stark black and white. As a political scientist wrote, “By the time the process culminates at the apex, the top-level officials are more often than not confronted with the task of deciding which set of decisions to accept. These official policy-makers, in many respects, become policy ratifiers” (Gawthrop, 1969).

How Congress Influences the Federal Bureaucracy

Congress makes laws fixing the functions, jurisdictions, and goals of agencies. It sets agency budgets and conditions for how funds must be used. It can demote, merge, or abolish any agency it finds wanting; longevity does not guarantee survival (Lewis, 2002). Every agency’s challenge is to find ways to avoid such sanctions.

If an agency’s actions become politically unpopular, Congress can cut its budget, restrict the scope of regulation or the tools used, or specify different procedures. For example, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) in the early 1990s made a series of controversial decisions to fund gay and lesbian performance artists. The NEA’s budget was cut by Congress and its existence threatened. If such sanctions are seldom applied, their presence coaxes bureaucrats to anticipate and conform to what Congress wants.

Congress monitors agency activities by congressional oversight: the process by which Congress monitors the activities of government agencies. Members gather information on agency performance and communicate to agencies about how well or, more often, how poorly they are doing (Foreman Jr., 1988). Oversight ranges from a lone legislator’s intervention over a constituent’s late social security check to high-profile investigations and committee hearings. It is neither centralized nor systematic. Rather than rely on a “police-patrol” style of oversight—dutifully seeking information about what agencies are doing—Congress uses a “fire alarm” approach: interest groups and citizens alert members to problems in an agency, often through reports in the news (McCubbins & Schwartz, 1984).

How Agencies Influence Congress

Agencies can work for continued congressional funding by building public support for the agency and its programs. The huge budget of the Defense Department is facilitated when public opinion polls accord high confidence to the military. To keep this confidence high is one reason the Defense Department aggressively interacts with the media to obtain favorable coverage.

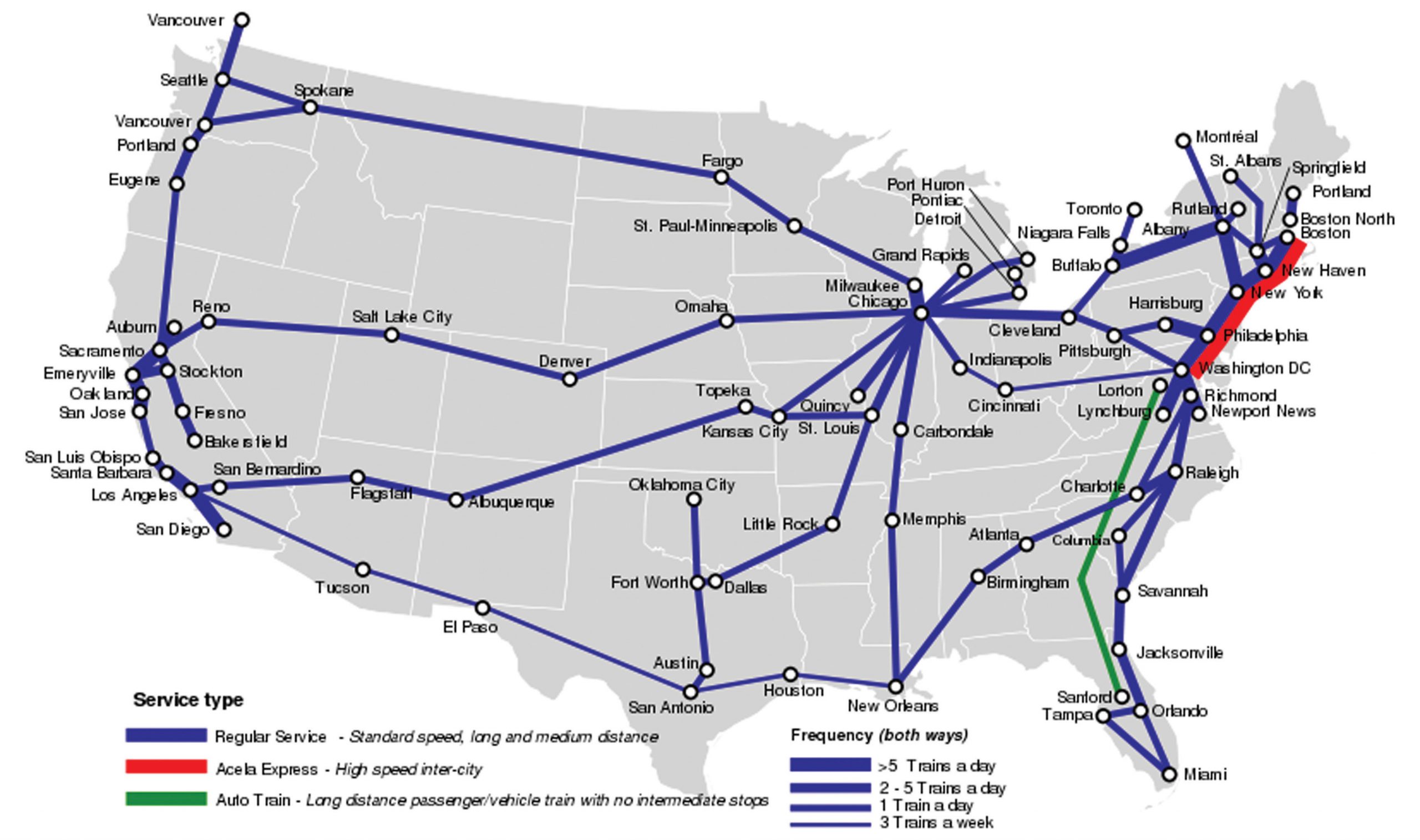

Agencies can make it hard for Congress to close them down or reduce their budget even when public opinion is mixed. Agencies choose how much money to spend in implementing a program; they spread resources across many districts and states in the hope that affected legislators will be less inclined to oppose their programs (Arnold, 1979).For example, numerous presidents have proposed that the perennially money-losing government corporation Amtrak be “zeroed out.” But Amtrak has survived time and again. Why? Although train riders are few outside the Northeast, Amtrak trains regularly serve almost all the continental forty-eight states, providing local pressure to keep a national train system going.

Likewise, when faced with extinction, an agency can alter its policies to affect more congressional constituencies. For example, after the NEA was threatened with extinction, it shifted funding away from supporting artists in trendy urban centers and toward building audiences for community-sponsored arts found in a multitude of districts and states—whose residents could push Congress to increase the NEA’s budget. Sure enough, President Bush’s tight budgets saw rises for the NEA.

OPPORTUNITY AND LEGACY

What often shapes a president’s performance, reputation, and ultimately legacy depends on circumstances that are largely out of their control. Did the president prevail in a landslide or was it a closely contested election? Did they come to office as the result of death, assassination, or resignation? How much support does the president’s party enjoy, and is that support reflected in the composition of both houses of Congress, just one, or neither? Will the president face a Congress ready to embrace proposals or poised to oppose them? Whatever a president’s ambitions, it will be hard to realize them in the face of a hostile or divided Congress, and the options to exercise independent leadership are greater in times of crisis and war than when looking at domestic concerns alone.

Then there is what political scientist Stephen Skowronek calls “political time.”53 Some presidents take office at times of great stability with few concerns. Unless there are radical or unexpected changes, a president’s options are limited, especially if voters hoped for a simple continuation of what had come before. Other presidents take office at a time of crisis or when the electorate is looking for significant changes. Then there is both pressure and opportunity for responding to those challenges. Some presidents, notably Theodore Roosevelt, openly bemoaned the lack of any such crisis, which Roosevelt deemed essential for him to achieve greatness as a president.

People in the United States claim they want a strong president. What does that mean? At times, scholars point to presidential independence, even defiance, as evidence of strong leadership. Thus, vigorous use of the veto power in key situations can cause observers to judge a president as strong and independent, although far from effective in shaping constructive policies. Nor is such defiance and confrontation always evidence of presidential leadership skill or greatness, as the case of Andrew Johnson should remind us. When is effectiveness a sign of strength, and when are we confusing being headstrong with being strong? Sometimes, historians and political scientists see cooperation with Congress as evidence of weakness, as in the case of Ulysses S. Grant, who was far more effective in garnering support for administration initiatives than scholars have given him credit for.

These questions overlap with those concerning political time and circumstance. While domestic policymaking requires far more give-and-take and a fair share of cajoling and collaboration, national emergencies and war offer presidents far more opportunity to act vigorously and at times independently. This phenomenon often produces the rally around the flag effect, in which presidential popularity spikes during international crises. A president must always be aware that politics, according to Otto von Bismarck, is the art of the possible, even as it is a president’s duty to increase what might be possible by persuading both members of Congress and the general public of what needs to be done.

Finally, presidents often leave a legacy that lasts far beyond their time in office (Figure 12.21). Sometimes, this is due to the long-term implications of policy decisions. Critical to the notion of legacy is the shaping of the Supreme Court as well as other federal judges. Long after John Adams left the White House in 1801, his appointment of John Marshall as chief justice shaped American jurisprudence for over three decades. No wonder confirmation hearings have grown more contentious in the cases of highly visible nominees. Other legacies are more difficult to define, although they suggest that, at times, presidents cast a long shadow over their successors. It was a tough act to follow George Washington, and in death, Abraham Lincoln’s presidential stature grew to extreme heights. Theodore and Franklin D. Roosevelt offered models of vigorous executive leadership, while the image and style of John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan influenced and at times haunted or frustrated successors. Nor is this impact limited to chief executives deemed successful: Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam and Richard Nixon’s Watergate offered cautionary tales of presidential power gone wrong, leaving behind legacies that include terms like Vietnam syndrome and the tendency to add the suffix “-gate” to scandals and controversies.