Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How is the presidency personalized?

- What powers does the Constitution grant to the president?

- How can Congress and the judiciary limit the president’s powers?

- How is the presidency organized?

- What is the bureaucratizing of the presidency?

13.2 The Powers of the Presidency

The presidency is seen as the heart of the political system. It is personalized in the president as advocate of the national interest, chief agenda-setter, and chief legislator (Tulis, 1988). Scholars evaluate presidents according to such abilities as “public communication,” “organizational capacity,” “political skill,” “policy vision,” and “cognitive skill” (Greenstein, 2009). The media too personalize the office and push the ideal of the bold, decisive, active, public-minded president who altruistically governs the country (Smith, 2009).

News depictions of the White House also focus on the person of the president. They portray a “single executive image” with visibility no other political participant can boast. Presidents usually get positive coverage during crises foreign or domestic. The news media depict them speaking for and symbolically embodying the nation: giving a State of the Union address, welcoming foreign leaders, traveling abroad, representing the United States at an international conference. Ceremonial events produce laudatory coverage even during intense political controversy. The media are fascinated with the personality and style of individual presidents. They attempt to pin them down.

Enduring Image

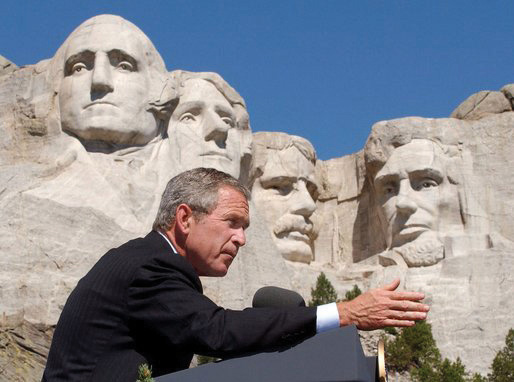

Mount Rushmore

Carved into the granite rock of South Dakota’s Mount Rushmore, seven thousand feet above sea level, are the faces of Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. The national monument, sculpted between 1927 and 1941, did not start out devoted to American presidents. It was initially proposed to acknowledge regional heroes: General Custer, Buffalo Bill, the explorers Lewis and Clark. The sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, successfully argued that “a nation’s memorial should…have a serenity, a nobility, a power that reflects the gods who inspired them and suggests the gods they have become” (Dean, 1949).

The Mount Rushmore monument is an enduring image of the American presidency by celebrating the greatness of four American presidents. The successors to Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Roosevelt do their part by trying to associate themselves with the office’s magnificence and project an image of consensus rather than conflict, sometimes by giving speeches at the monument itself. A George W. Bush event placed the presidential podium at such an angle that the television camera could not help but put the incumbent in the same frame as his glorious predecessors.

The enduring image of Mount Rushmore highlights and exaggerates the importance of presidents as the decision makers in the American political system. It elevates the president over the presidency, the occupant over the office. All depends on the greatness of the individual president—which means that the enduring image often contrasts the divinity of past presidents against the fallibility of the current incumbent.

The Presidency in the Constitution

Article II of the Constitution outlines the office of president. Specific powers are few; almost all are exercised in conjunction with other branches of the federal government.

Table 13.1 Bases for Presidential Powers in the Constitution

| Article I, Section 7, Paragraph 2 | Veto |

| Pocket veto | |

| Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 1 | “The Executive Power shall be vested in a President…” |

| Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 7 | Specific presidential oath of office stated explicitly (as is not the case with other offices) |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 | Commander in chief of armed forces and state militias |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 | Can require opinions of departmental secretaries |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 1 | Reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 2 | Make treaties |

| appoint ambassadors, executive officers, judges | |

| Article II, Section 2, Paragraph 3 | Recess appointments |

| Article II, Section 3 | State of the Union message and recommendation of legislative measures to Congress |

| Convene special sessions of Congress | |

| Receive ambassadors and other ministers | |

| “He shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” |

Presidents exercise only one power that cannot be limited by other branches: the pardon. So controversial decisions like President Gerald Ford’s pardon of his predecessor Richard Nixon for “crimes he committed or may have committed” or President Jimmy Carter’s blanket amnesty to all who avoided the draft during the Vietnam War could not have been overturned.

Presidents have more powers and responsibilities in foreign and defense policy than in domestic affairs. They are the commanders in chief of the armed forces; they decide how (and increasingly when) to wage war. Presidents have the power to make treaties to be approved by the Senate; the president is America’s chief diplomat. As head of state, the president speaks for the nation to other world leaders and receives ambassadors.

The Constitution directs presidents to be part of the legislative process. In the annual State of the Union address, presidents point out problems and recommend legislation to Congress. Presidents can convene special sessions of Congress, possibly to “jump-start” discussion of their proposals. Presidents can veto a bill passed by Congress, returning it with written objections. Congress can then override the veto. Finally, the Constitution instructs presidents to be in charge of the executive branch. Along with naming judges, presidents appoint ambassadors and executive officers. These appointments require Senate confirmation. If Congress is not in session, presidents can make temporary appointments known as recess appointments without Senate confirmation, good until the end of the next session of Congress.

The Constitution’s phrase “he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” gives the president the job to oversee the implementation of laws. Thus presidents are empowered to issue executive orders to interpret and carry out legislation. They supervise other officers of the executive branch and can require them to justify their actions.

Finally, the president’s job includes nominating federal judges, including Supreme Court justices, as well as other federal officials, and making appointments to fill military and diplomatic posts. The number of judicial appointments and nominations of other federal officials is great. In recent decades, two-term presidents have nominated well over three hundred federal judges while in office.10 Moreover, new presidents nominate close to five hundred top officials to their Executive Office of the President, key agencies (such as the Department of Justice), and regulatory commissions (such as the Federal Reserve Board), whose appointments require Senate majority approval.11

Congressional Limitations on Presidential Power

Almost all presidential powers rely on what Congress does (or does not do). Presidential executive orders implement the law but Congress can overrule such orders by changing the law. And many presidential powers are delegated powers that Congress has accorded presidents to exercise on its behalf—and that it can cut back or rescind.

Congress can challenge presidential powers single-handedly. One way is to amend the Constitution. The Twenty-Second Amendment was enacted in the wake of the only president to serve more than two terms, the powerful Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR). Presidents now may serve no more than two terms. The last presidents to serve eight years, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barrack Obama, quickly became “lame ducks” after their reelection and lost momentum toward the ends of their second terms, when attention switched to contests over their successors.

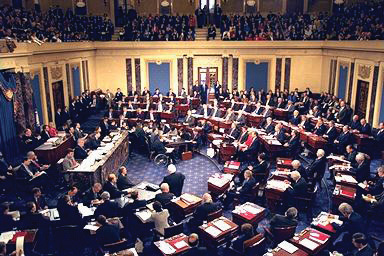

Impeachment gives Congress “sole power” to remove presidents (among others) from office. The language in the Constitution comes from Article I, Section 2, Clause 5, and Article I, Section 3, Clause 7. It works in two stages. The House of Representatives decides whether or not to accuse the president of wrongdoing. If a simple majority in the House votes to impeach the president, the Senate acts as jury, House members are prosecutors, and the chief justice of the Supreme Court may preside. A two-thirds vote by the Senate is necessary for conviction, the punishment for which is removal and disqualification from office.

Prior to the 1970s, presidential impeachment was deemed the founders’ “rusted blunderbuss that will probably never be taken in hand again” (Labowitz, 1978). Only one president (Andrew Johnson in 1868) had been impeached—over policy disagreements with Congress on the Reconstruction of the South after the Civil War. Johnson avoided removal by a single senator’s vote. Since the 1970s, the blunderbuss has been dusted off. A bipartisan majority of the House Judiciary Committee recommended the impeachment of President Nixon in 1974. Nixon surely would have been impeached and convicted had he not resigned first. President Clinton was impeached by the House in 1998, though acquitted by the Senate in 1999, for perjury and obstruction of justice in the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

The most recent impeachments were of President Donald Trump, who was impeached in the House twice. However, support for removal in the Senate did not meet the super-majority requirement, although on the second attempt in 2021 a solid majority favored removal. The first Trump impeachment brought charges of “abuse of power” and “obstruction of Congress” related to allegations that he improperly used his office to seek help from Ukrainian officials to facilitate his re-election. The second Trump impeachment was for “incitement of insurrection” related to the attack on the U.S. Capitol building during the counting of Electoral College votes on January 6, 2021. This second impeachment led to Republicans supporting impeachment in the House, including Representative Liz Cheney (R-WY), one of the central party leaders, and removal in the Senate, including Senator Mitt Romney (R-UT).7 Ongoing federal investigations of the insurrection continue, and an attempt to launch an independent commission to investigate the event (similar to the 9/11 commission) passed the House, but was blocked by Republicans in the Senate.8

Looking across the span of U.S. history, impeachment of a president remains a rare event indeed and removal has never occurred. However, with three of the five impeachment trials having occurred in the last twenty-five years, and with two of the five most recent presidents having faced impeachment, it will be interesting to watch if the trend continues in our partisan era. The fact that a president could be impeached and removed is an important reminder of the role of the executive in the broader system of shared powers.

Judicial Limitations on Presidential Power

Presidents claim inherent powers not explicitly stated but that are intrinsic to the office or implied by the language of the Constitution. They rely on three key phrases. First, in contrast to Article I’s detailed powers of Congress, Article II states that “The Executive Power shall be vested in a President.” Second, the presidential oath of office is spelled out, implying a special guardianship of the Constitution. Third, the job of ensuring that “the Laws be faithfully executed” can denote a duty to protect the country and political system as a whole.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court can and does rule on whether presidents have inherent powers. Its rulings have both expanded and limited presidential power. For instance, the justices concluded in 1936 that the president, the embodiment of the United States outside its borders, can act on its behalf in foreign policy.

But the court usually looks to congressional action (or inaction) to define when a president can invoke inherent powers. In 1952, President Harry Truman claimed inherent emergency powers during the Korean War. Facing a steel strike he said would interrupt defense production, Truman ordered his secretary of commerce to seize the major steel mills and keep production going. The Supreme Court rejected this move: “the President’s power, if any, to issue the order must stem either from an act of Congress or from the Constitution itself.”

The Vice Presidency

Only two positions in the presidency are elected: the president and vice president. With ratification of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment in 1967, a vacancy in the latter office may be filled by the president, who appoints a vice president subject to majority votes in both the House and the Senate. This process was used twice in the 1970s. Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned amid allegations of corruption; President Nixon named House Minority Leader Gerald Ford to the post. When Nixon resigned during the Watergate scandal, Ford became president—the only person to hold the office without an election—and named former New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller vice president.

The vice president’s sole duties in the Constitution are to preside over the Senate and cast tie-breaking votes, and to be ready to assume the presidency in the event of a vacancy or disability. Eight of the forty-six presidents (actually 45 persons, Grover Cleveland served 2 non-consecutive terms) had been vice presidents who succeeded a dead president (four times from assassinations). Otherwise, vice presidents have few official tasks. The first vice president, John Adams, told the Senate, “I am Vice President. In this I am nothing, but I may be everything.” More earthily, FDR’s first vice president, John Nance Garner, called the office “not worth a bucket of warm piss.”

In recent years, vice presidents are more publicly visible and have taken on more tasks and responsibilities. Ford and Rockefeller began this trend in the 1970s, demanding enhanced day-to-day responsibilities and staff as conditions for taking the job. Vice presidents now have a West Wing office, are given prominent assignments, and receive distinct funds for a staff under their control parallel to the president’s staff (Light, 1984).

Arguably the most powerful occupant of the office ever was Dick Cheney. This former doctoral candidate in political science (at the University of Wisconsin) had been a White House chief of staff, member of Congress, and cabinet secretary. He possessed an unrivaled knowledge of the power relations within government and of how to accumulate and exercise power. As George W. Bush’s vice president, he had access to every cabinet and subcabinet meeting he wanted to attend, chaired the board charged with reviewing the budget, took on important issues (security, energy, economy), ran task forces, was involved in nominations and appointments, and lobbied Congress (Gellman & Becker, 2007).

THE EVOLVING POWERS OF THE EXECUTIVE BRANCH

No sooner had the presidency been established than the occupants of the office, starting with George Washington, began acting in ways that expanded both its formal and informal powers. For example, Washington established a cabinet or group of advisors to help him administer his duties, consisting of the most senior appointed officers of the executive branch. Today, the heads of the fifteen executive departments serve as the president’s advisers.

Of the many ways in which the chief executive’s power grown over time, the most significant is the expansion of presidential war powers. Over the course of the twentieth century, presidents expanded and elaborated upon these powers. The rather vague wording in Article II, which says that the “executive power shall be vested” in the president, has been subject to broad and sweeping interpretation in order to justify actions beyond those specifically enumerated in the document.15 As the federal bureaucracy expanded, so too did the president’s power to grow agencies like the Secret Service and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Presidents also further developed the concept of executive privilege, the right to withhold information from Congress, the judiciary, or the public. This right, not enumerated in the Constitution, was first asserted by George Washington to curtail inquiry into the actions of the executive branch.16 The more general defense of its use by White House officials and attorneys ensures that the president can secure candid advice from advisors and staff members.

Increasingly over time, presidents have made more use of their unilateral powers, including executive orders, rules that bypass Congress but still have the force of law if the courts do not overturn them. More recently, presidents have offered their own interpretation of legislation as they sign it via signing statements (discussed later in this chapter) directed to the bureaucratic entity charged with implementation. In the realm of foreign policy, Congress permitted the widespread use of executive agreements to formalize international relations, so long as important matters still came through the Senate in the form of treaties.17 Recent presidents have continued to rely upon an ever more expansive definition of war powers to act unilaterally at home and abroad. Finally, presidents, often with Congress’s blessing through the formal delegation of authority, have taken the lead in framing budgets, negotiating budget compromises, and at times impounding funds in an effort to prevail in matters of policy.

The growth of presidential power is also attributable to the growth of the United States and the power of the national government. As the nation has grown and developed, so has the office. Whereas most important decisions were once made at the state and local levels, the increasing complexity and size of the domestic economy have led people in the United States to look to the federal government more often for solutions. At the same time, the rising profile of the United States on the international stage has meant that the president is a far more important figure as leader of the nation, as diplomat-in-chief, and as commander-in-chief. Finally, with the rise of electronic mass media, a president who once depended on newspapers and official documents to distribute information beyond an immediate audience can now bring that message directly to the people via radio, television, and social media. Major events and crises, such as the Great Depression, two world wars, the Cold War, and the war on terrorism, have further contributed to presidential stature.

Bureaucratizing the Presidency

In many ways “the institution makes presidents as much if not more than presidents make the institution” (Ragsdale & Theis III, 1997; Burke, 2000). The presidency became a complex institution starting with FDR, who was elected to four terms during the Great Depression and World War II. Prior to FDR, presidents’ staffs were small. As presidents took on responsibilities and jobs, often at Congress’s initiative, the presidency grew and expanded. Not only is the presidency bigger since FDR, but the division of labor within an administration is far more complex. The Cabinet, the Executive Office of the President (EOP), and the White House Office (WHO), each described in the next section, consist of hundreds of staffers who almost all either have a substantive specialty (e.g., national security, women’s initiatives, environment, health policy) or emphasize specific activities (e.g., White House legal counsel, director of press advance, public liaison, legislative liaison, chief speechwriter, director of scheduling). These staffers “make a great many decisions themselves, acting in the name of the president. In fact, the majority of White House decisions—all but the most crucial—are made by presidential assistants” (Kessel, 2001).

Exercises

- How do the media personalize the presidency?

- How can the president check the power of Congress? How can Congress limit the influence of the president?

- How is the executive branch organized? How is the way the executive branch operates different from the way it is portrayed in the media?

References

Andrews, E. L., “Economics Adviser Learns the Principles of Politics,” New York Times, February 26, 2004, C4.

Benedict, M. L., The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson (New York: Norton, 1973), 139.

Burke, J. P., The Institutional Presidency, 2nd ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

Bush at War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002).

Crowley, S., “And on the 96th Day…,” New York Times, April 29, 2001, Week in Review, 3.

Dean, R. J., Living Granite (New York: Viking Press, 1949), 18.

Gellman, B. and Jo Becker, “Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency,” Washington Post, June 24, 2007, A1.

Greenstein, F. I., The Presidential Difference: Leadership Style from FDR to Barack Obama, 3rd ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009).

Kakutani, M., “A Portrait of the President as the Victim of His Own Certitude,” review of State of Denial: Bush at War, Part III, by Bob Woodward, New York Times, September 30, 2006, A15.

Kessel, J. H., Presidents, the Presidency, and the Political Environment (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2001), 2.

Labowitz, J. R., Presidential Impeachment (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978), 91.

Larson, S. G., “Political Cynicism and Its Contradictions in the Public, News, and Entertainment,” in It’s Show Time! Media, Politics, and Popular Culture, ed. David A. Schultz (New York: Peter Lang, 2000), 101–116.

Light, P. C., Vice-Presidential Power: Advice and Influence in the White House (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984).

Parry-Giles, T. and Shawn J. Parry-Giles, The Prime-Time Presidency: The West Wing and U.S. Nationalism (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2006).

Polling Report, http://www.pollingreport.com/bush.htm, accessed July 7, 2005.

Ragsdale, L. and John J. Theis III, “The Institutionalization of the American Presidency, 1924–92,” American Journal of Political Science 41, no. 4 (October 1997): 1280–1318 at 1316.

Sachleben, M. and Kevan M. Yenerall, Seeing the Bigger Picture: Understanding Politics through Film and Television (New York: Peter Lang, 2004), chap. 4.

Smith, J., The Presidents We Imagine (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009).

Tulis, J. K., The Rhetorical Presidency (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988).