Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe political parties and what they do

- Differentiate political parties from interest groups

- Explain how U.S. political parties formed

Political parties are groups of people with similar interests who work together to create and implement policies. They do this by gaining control over the government by winning elections. Party platforms guide members of Congress in drafting legislation. Parties guide proposed laws through Congress and inform party members how they should vote on important issues. Political parties also nominate candidates to run for state government, Congress, and the presidency. Finally, they coordinate political campaigns and mobilize voters.

The endurance and adaptability of American political parties is best understood by examining their colorful historical development. Parties evolved from factions in the eighteenth century to political machines in the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, parties underwent waves of reform that some argue initiated a period of decline. The renewed parties of today are service-oriented organizations dispensing assistance and resources to candidates and politicians (Aldrich, 1995; Eldersveld & Walton Jr., 2000).

POLITICAL PARTIES AS UNIQUE ORGANIZATIONS

In Federalist No. 10, written in the late eighteenth century, James Madison noted that the formation of self-interested groups, which he called factions,

was inevitable in any society, as individuals started to work together to protect themselves from the government. Interest groups and political parties are two of the most easily identified forms of factions in the United States. These groups are similar in that they are both mediating institutions responsible for communicating public preferences to the government. They are not themselves government institutions in a formal sense. Neither is directly mentioned in the U.S. Constitution nor do they have any real, legal authority to influence policy. But whereas interest groups often work indirectly to influence our leaders, political parties are organizations that try to directly influence public policy through its members who seek to win and hold public office. Parties accomplish this by identifying and aligning sets of issues that are important to voters in the hopes of gaining support during elections; their positions on these critical issues are often presented in documents known as a party platform, which is adopted at each party’s presidential nominating convention every four years. If successful, a party can create a large enough electoral coalition to gain control of the government. Once in power, the party is then able to deliver, to its voters and elites, the policy preferences they choose by electing its partisans to the government. In this respect, parties provide choices to the electorate, something they are doing that is in such sharp contrast to their opposition.

LINK TO LEARNING

You can read the full platform of Today’s Republican Party and the Democratic Party at their respective websites.

Winning elections and implementing policy would be hard enough in simple political systems, but in a country as complex as the United States, political parties must take on great responsibilities to win elections and coordinate behavior across the many local, state, and national governing bodies. Indeed, political differences between states and local areas can contribute much complexity. If a party stakes out issue positions on which few people agree and therefore builds too narrow a coalition of voter support, that party may find itself marginalized. But if the party takes too broad a position on issues, it might find itself in a situation where the members of the party disagree with one another, making it difficult to pass legislation, even if the party can secure victory.

It should come as no surprise that the story of U.S. political parties largely mirrors the story of the United States itself. The United States has seen sweeping changes to its size, its relative power, and its social and demographic composition. These changes have been mirrored by the political parties as they have sought to shift their coalitions to establish and maintain power across the nation and as party leadership has changed. As you will learn later, this also means that the structure and behavior of modern parties largely parallel the social, demographic, and geographic divisions within the United States today. To understand how this has happened, we look at the origins of the U.S. party system.

Parties as Factions

The first American party system had its origins in the period following the Revolutionary War. Despite Madison’s warning in Federalist No. 10, the first parties began as political factions. Upon taking office in 1789, President George Washington sought to create an “enlightened administration” devoid of political parties (White & Shea, 2000). He appointed two political adversaries to his cabinet, Alexander Hamilton as treasury secretary and Thomas Jefferson as secretary of state, hoping that the two great minds could work together in the national interest. Washington’s vision of a government without parties, however, was short-lived.

Hamilton and Jefferson differed radically in their approaches to rectifying the economic crisis that threatened the new nation (Charles, 1956). Hamilton proposed a series of measures, including a controversial tax on whiskey and the establishment of a national bank. He aimed to have the federal government assume the entire burden of the debts incurred by the states during the Revolutionary War. Jefferson, a Virginian who sided with local farmers, fought this proposition. He believed that moneyed business interests in the New England states stood to benefit from Hamilton’s plan. Hamilton assembled a group of powerful supporters to promote his plan, a group that eventually became the Federalist Party (Hofstadter, 1969).

The Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans

The Federalist Party originated at the national level but soon extended to the states, counties, and towns. Hamilton used business and military connections to build the party at the grassroots level, primarily in the Northeast. Because voting rights had been expanded during the Revolutionary War, the Federalists sought to attract voters to their party. They used their newfound organization for propagandizing and campaigning for candidates. They established several big-city newspapers to promote their cause, including the Gazette of the United States, the Columbian Centinel, and the American Minerva, which were supplemented by broadsheets in smaller locales. This partisan press initiated one of the key functions of political parties—articulating positions on issues and influencing public opinion (Chambers, 1963).

Disillusioned with Washington’s administration, especially its foreign policy, Jefferson left the cabinet in 1794. Jefferson urged his friend James Madison to take on Hamilton in the press, stating, “For God’s sake, my Dear Sir, take up your pen, select your most striking heresies, and cut him to pieces in the face of the public” (Chambers, 1963). Madison did just that under the pen name of Helvidius. His writings helped fuel an anti-Federalist opposition movement, which provided the foundation for the Democratic-Republican Party. This early Party differed from the present-day parties which use those same names (This historical roots of Today’s Democratic Party is the old Democratic-Republican Party). Opposition newspapers, the National Gazette and the Aurora, communicated the Democratic-Republicans’ views and actions, and inspired local groups and leaders to align themselves with the emerging party (Chambers, 1963). The Whiskey Rebellion in 1794, staged by farmers angered by Hamilton’s tax on whiskey, reignited the founders’ fears that violent factions could overthrow the government (Schudson, 1998).

First Parties in a Presidential Election

Political parties were first evident in presidential elections in 1796, when Federalist John Adams was barely victorious over Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson. During the election of 1800, Democratic-Republican and Federalist members of Congress met formally to nominate presidential candidates, a practice that was a precursor to the nominating conventions used today. As the head of state and leader of the Democratic-Republicans, Jefferson established the American tradition of political parties as grassroots organizations that band together smaller groups representing various interests, run slates of candidates for office, and present issue platforms (White & Shea, 2000).

The early Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties consisted largely of political officeholders. The Federalists not only lacked a mass membership base but also were unable to expand their reach beyond the wealthy classes. As a result, the Federalists ceased to be a force after the 1816 presidential election, when they received few votes. The Democratic-Republican Party, bolstered by successful presidential candidates Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, was the sole surviving national party by 1820. Infighting soon caused the Democratic-Republicans to cleave into warring factions: the National Republican (which became the Whig Party) and the Democratic Party (Formisano, 1981).

Establishment of a Party System

A true political party system with two durable institutions associated with specific ideological positions and plans for running the government did not begin to develop until 1828. The Democratic-Republicans, which became the Democratic Party, elected their presidential candidate, Andrew Jackson. The Whig Party, an offshoot of the National Republicans, formed in opposition to the Democrats in 1834 (Holt, 2003).

The era of Jacksonian Democracy, which lasted until the outbreak of the Civil War, featured the rise of mass-based party politics. Both parties initiated the practice of grassroots campaigning, including door-to-door canvassing of voters and party-sponsored picnics and rallies. Citizens voted in record numbers, with turnouts as high as 96 percent in some states (Holt, 2003). Campaign buttons publically displaying partisan affiliation came into vogue. The spoils system, also known as patronage, where voters’ party loyalty was rewarded with jobs and favors dispensed by party elites, originated during this era.

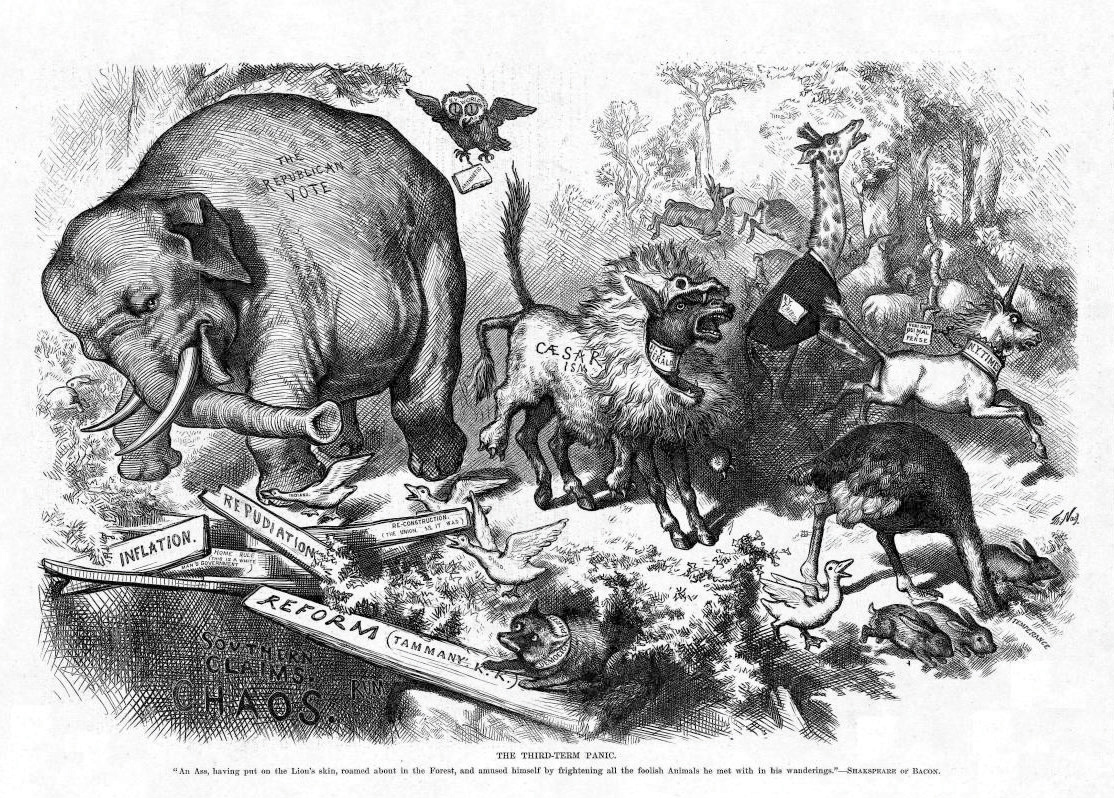

The two-party system consisting of the Democrats and Republicans was in place by 1860. The Whig Party had disintegrated as a result of internal conflicts over patronage and disputes over the issue of slavery. The Democratic Party, while divided over slavery, remained basically intact (Holt, 2003). The Republican Party was formed in 1854 during a gathering of former Whigs, disillusioned Democrats, and members of the Free-Soil Party, a minor antislavery party. The Republicans came to prominence with the election of Abraham Lincoln.

Parties as Machines

Parties were especially powerful in the post–Civil War period through the Great Depression, when more than 15 million people immigrated to the United States from Europe, many of whom resided in urban areas. Party machines, cohesive, authoritarian command structures headed by bosses who exacted loyalty and services from underlings in return for jobs and favors, dominated political life in cities. Machines helped immigrants obtain jobs, learn the laws of the land, gain citizenship, and take part in politics.

Machine politics was not based on ideology, but on loyalty and group identity. The Curley machine in Boston was made up largely of Irish constituents who sought to elect their own (White & Shea, 2000). Machines also brought different groups together. The tradition of parties as ideologically ambiguous umbrella organizations stems from Chicago-style machines that were run by the Daley family. The Chicago machine was described as a “hydra-headed monster” that “encompasses elements of every major political, economic, racial, ethnic, governmental, and paramilitary power group in the city” (Rakove, 1975). The idea of a “balanced ticket” consisting of representatives of different groups developed during the machine-politics era (Pomper, 1992).

Because party machines controlled the government, they were able to sponsor public works programs, such as roads, sewers, and construction projects, as well as social welfare initiatives, which endeared them to their followers. The ability of party bosses to organize voters made them a force to be reckoned with, even as their tactics were questionable and corruption was rampant (Riechley, 1992). Bosses such as William Tweed in New York were larger-than-life figures who used their powerful positions for personal gain. Tammany Hall boss George Washington Plunkitt describes what he called “honest graft”:

My party’s in power in the city, and its goin’ to undertake a lot of public improvements. Well, I’m tipped off, say, that they’re going to lay out a new park at a certain place. I see my opportunity and I take it. I go to that place and I buy up all the land I can in the neighborhood. Then the board of this or that makes the plan public, and there is a rush to get my land, which nobody cared particular for before. Ain’t it perfectly honest to charge a good price and make a profit on my investment and foresight? Of course, it is. Well, that’s honest graft (Riordon, 1994).

Parties Reformed

Not everyone benefited from political machines. There were some problems that machines either could not or would not deal with. Industrialization and the rise of corporate giants created great disparities in wealth. Dangerous working conditions existed in urban factories and rural coal mines. Farmers faced falling prices for their products. Reformers blamed these conditions on party corruption and inefficiency. They alleged that party bosses were diverting funds that should be used to improve social conditions into their own pockets and keeping their incompetent friends in positions of power.

The Progressive Era

The mugwumps, reformers who declared their independence from political parties, banded together in the 1880s and provided the foundation for the Progressive Movement. The Progressives initiated reforms that lessened the parties’ hold over the electoral system. Voters had been required to cast color-coded ballots provided by the parties, which meant that their vote choice was not confidential. The Progressives succeeded by 1896 in having most states implement the secret ballot. The secret ballot is issued by the state and lists all parties and candidates. This system allows people to split their ticket when voting rather than requiring them to vote the party line. The Progressives also hoped to lessen machines’ control over the candidate selection process. They advocated a system of direct primary elections in which the public could participate rather than caucuses, or meetings of party elites. The direct primary had been instituted in only a small number of states, such as Wisconsin, by the early years of the twentieth century. The widespread use of direct primaries to select presidential candidates did not occur until the 1970s.

The Progressives sought to end party machine dominance by eliminating the patronage system. Instead, employment would be awarded on the basis of qualifications rather than party loyalty. The merit system, now called the civil service, was instituted in 1883 with the passage of the Pendleton Act. The merit system wounded political machines, although it did not eliminate them (Merriam & Gosnell, 1922).

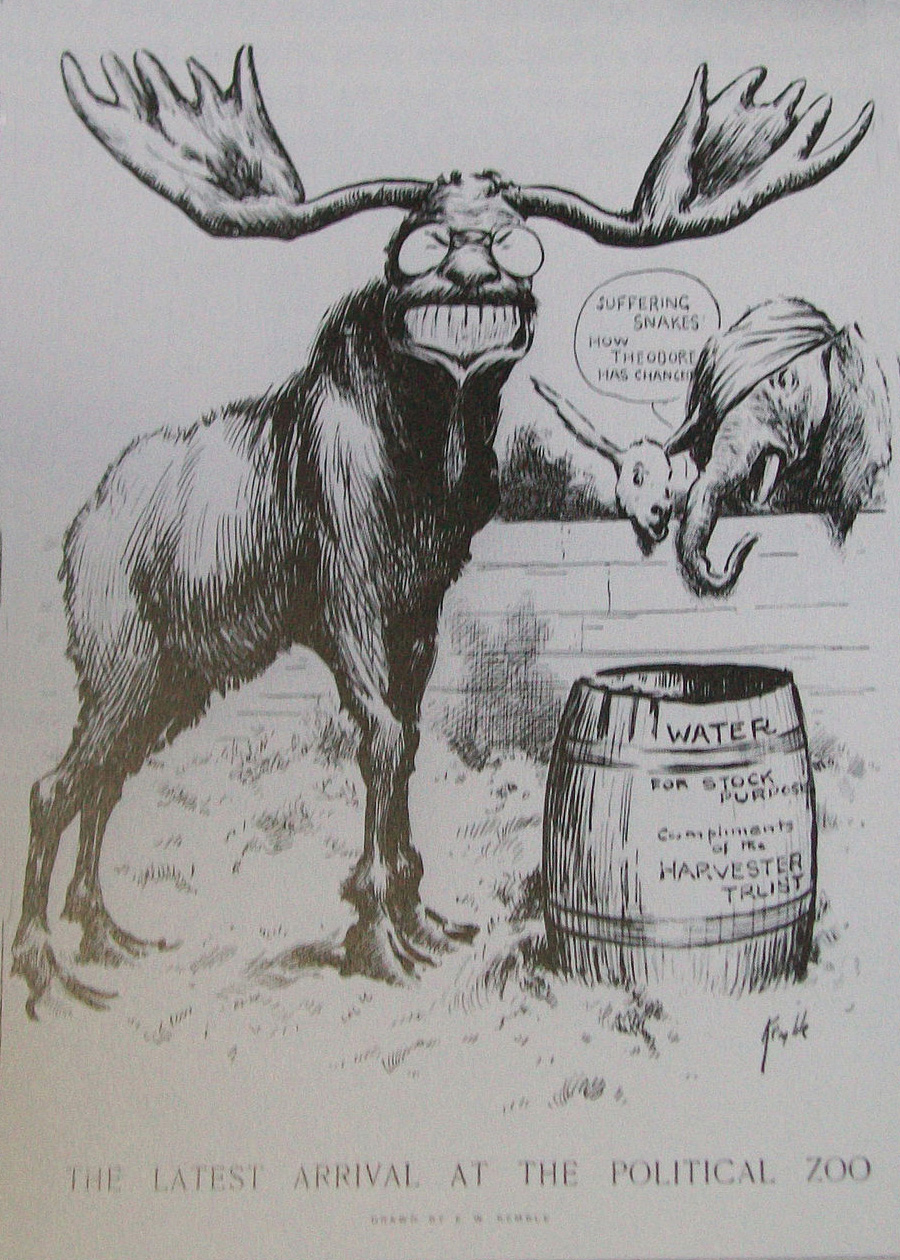

Progressive reformers ran for president under party labels. Former president Theodore Roosevelt split from the Republicans and ran as the Bull Moose Party candidate in 1912, and Robert LaFollette ran as the Progressive Party candidate in 1924. Republican William Howard Taft defeated Roosevelt, and LaFollette lost to Republican Calvin Coolidge.

New Deal and Cold War Eras

Democratic President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal program for leading the United States out of the Great Depression in the 1930s had dramatic effects on political parties. The New Deal placed the federal government in the pivotal role of ensuring the economic welfare of citizens. Both major political parties recognized the importance of being close to the power center of government and established national headquarters in Washington, DC.

An era of executive-centered government also began in the 1930s, as the power of the president was expanded. Roosevelt became the symbolic leader of the Democratic Party (Riechley, 1992). Locating parties’ control centers in the national capital eventually weakened them organizationally, as the basis of their support was at the local grassroots level. National party leaders began to lose touch with their local affiliates and constituents. Executive-centered government weakened parties’ ability to control the policy agenda (White & Shea, 2000).

The Cold War period that began in the late 1940s was marked by concerns over the United States’ relations with Communist countries, especially the Soviet Union. Following in the footsteps of the extremely popular president Franklin Roosevelt, presidential candidates began to advertise their independence from parties and emphasized their own issue agendas even as they ran for office under the Democratic and Republican labels. Presidents, such as Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush, won elections based on personal, rather than partisan, appeals (Caeser, 1979).

Candidate-Centered Politics

Political parties instituted a series of reforms beginning in the late 1960s amid concerns that party elites were not responsive to the public and operated secretively in so-called smoke-filled rooms. The Democrats were the first to act, forming the McGovern-Fraser Commission to revamp the presidential nominating system. The commission’s reforms, adopted in 1972, allowed more average voters to serve as delegates to the national party nominating convention, where the presidential candidate is chosen. The result was that many state Democratic parties switched from caucuses, where convention delegates are selected primarily by party leaders, to primary elections, which make it easier for the public to take part. The Republican Party soon followed with its own reforms that resulted in states adopting primaries (Crotty, 1984).

The unintended consequence of reform was to diminish the influence of political parties in the electoral process and to promote the candidate-centered politics that exists today. Candidates build personal campaign organizations rather than rely on party support. The media have contributed to the rise of candidate-centered politics. Candidates can appeal directly to the public through television rather than working their way through the party apparatus when running for election (Owen, 1991). Candidates use social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, to connect with voters. Campaign professionals and media consultants assume many of the responsibilities previously held by parties, such as developing election strategies and getting voters to the polls.

Key Takeaways

Political parties are enduring organizations that run candidates for office. American parties developed quickly in the early years of the republic despite concerns about factions expressed by the founders. A true, enduring party system developed in 1828. The two-party system of Democrats and Republicans was in place before the election of President Abraham Lincoln in 1860.

Party machines became powerful in the period following the Civil War when an influx of immigrants brought new constituents to the country. The Progressive Movement initiated reforms that fundamentally changed party operations. Party organizations were weakened during the period of executive-centered government that began during the New Deal.

Reforms of the party nominating system resulted in the rise of candidate-centered politics beginning in the 1970s. The media contributes to candidate-centered politics by allowing candidates to take their message to the public directly without the intervention of parties.

Exercises

- What did James Madison mean by “the mischiefs of faction?” What is a faction? What are the dangers of factions in politics?

- What role do political parties play in the US political system? What are the advantages and disadvantages of the party system?

- How do contemporary political parties differ from parties during the era of machine politics? Why did they begin to change?

References

Aldrich, J. H., Why Parties? The Origin and Transformation of Party Politics in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995)

Caeser, J. W., Presidential Selection (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979).

Chambers, W. N., Political Parties in a New Nation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1963).

Chambers, W. N. and Walter Dean Burnham, The American Party Systems (New York, Oxford University Press, 1975).

Charles, J., The Origins of the American Party System (New York: Harper & Row, 1956).

Crotty, W., American Parties in Decline (Boston: Little, Brown, 1984).

Eldersveld, S. J. and Hanes Walton Jr., Political Parties in American Society, 2nd ed. (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000).

Epstein, L. D., Political Parties in the American Mold (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1986), 3.

Formisano, R. P., “Federalists and Republicans: Parties, Yes—System, No,” in The Evolution of the American Electoral Systems, ed. Paul Kleppner, Walter Dean Burnham, Ronald P. Formisano, Samuel P. Hays, Richard Jensen, and William G. Shade (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981), 37–76.

Hofstadter, R., The Idea of a Party System (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), 200.

Holt, M. F., The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Kandall, J., “Boss,” Smithsonian Magazine, February 2002, accessed March 23, 2011, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/boss.html.

Key Jr., V. O., Politics, Parties, & Pressure Groups, 5th ed. (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1964).

Merriam, C. and Harold F. Gosnell, The American Party System (New York: MacMillan, 1922).

Owen, D., Media Messages in American Presidential Elections (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1991).

Pomper, G. M., Passions and Interests (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992).

Publius (James Madison), “The Federalist No. 10,” in The Federalist, ed. Robert Scigliano (New York: The Modern Library Classics, 2001), 53–61.

Rakove, M., Don’t Make No Waves, Don’t Back No Losers: An Insider’s Analysis of the Daley Machine (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975), 3.

Riechley, A. J., The Life of the Parties (New York: Free Press, 1992).

Riordon, W. L., Plunkitt of Tammany Hall (St. James, NY: Brandywine Press, 1994), 3.

Schudson, M., The Good Citizen (New York: Free Press, 1998).

White, J. K. and Daniel M. Shea, New Party Politics (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000).