9 How Social Media Platforms Intersect With News

Take a moment to think about the last news item you read, heard, or watched. How did you encounter it? Were you looking for it or did it come looking for you? Were you visiting a news site online to see what’s happening? Catch it on the radio while driving to work? Did you hear about it from a friend or teacher? Was it something that caught your eye when skimming a news app on your phone? Or while checking your favorite social media platform?

Information networks that don’t create news are increasingly important discovery and distribution routes. Content created by news organizations spreads through social media when people share links and as the organizations promote their own content through Facebook, Snapchat, and elsewhere. This has benefits – news can reach people where they are and acquaintances can amplify the reach of a news story through a network of trust – but the downsides include organizations having to share dwindling ad revenue with the platforms and being at the whim of companies that can change their algorithms at any time without warning or consultation.

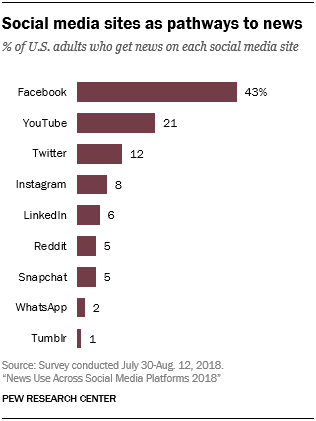

But social media is where news is at. A survey conducted by Pew Research in 2018 found two-thirds of American adults report getting news through social media, with Facebook and YouTube leading other platforms.

Another study by Project Information Literacy involving nearly 6,000 college students at 11 institutions found nearly 90 percent of students got news through social media, second only to hearing about it from friends face-to-face or through online channels. A large majority said journalism is necessary for democracy but most find it hard to keep up and half weren’t confident they could identify whether a news story was fake or not. Over a third doubted the credibility of all news.

Alternative News, Alternative Facts

But it’s not all about how journalism travels. Social platforms enable the creation of new information channels that challenge the dominance of traditional news organizations. That’s not all bad. New players can provide valuable alternative viewpoints and cover news ignored by the mainstream, but it also enables the creation and spread of misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda. The incentives built into social networks promote the use of emotional appeals and reward “influencers” who engage large audiences by any means necessary. The more outrageous, the more they are richly rewarded. While reputations matter in these new information channels, they are not dependent on old-school journalistic values or practices. For example, a conspiracy theory about murders of South African farmers that circulated in white supremacist circles for years broke into the mainstream when a claim by a “citizen journalist” on YouTube was repeated by Tucker Carlson and then by the president in a Tweet.

Social platforms, meeting with new criticism, want to avoid taking responsibility for what appears on their platforms. While they will take material down if it violates their terms of use or is illegal (child pornography or copyright violations, for example), they rely on a provision of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 that immunizes internet providers.

No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.

Of course, this law predates the social platforms we use today and their meteoric rise to the top of the list of the world’s most valuable corporations. Lawmakers in 1996 had no way of knowing billions of people would be using and contributing material through the internet, that we would be accessing volumes of information through our phones. They might have had reservations if they imagined a world where 300 hours of video would be uploaded to a single website every minute, that messages could rocket around the world instantly, that governments could be toppled or could undermine one another covertly through disinformation campaigns. Section 230 of the Act gave entrepreneurs the freedom to create new things. It also let them off the hook for the problems we’re dealing with today. The consequences of this laissez-faire attitude are becoming more clear by the day, and platforms are scrambling to balance the ability of anyone to publish and share anything with the political and social fallout.

If you want to understand information, it’s important to understand how information networks operate. Profiles of major social platforms will be presented in Part Three of this book.