The Spirit in Diverse Guises

Christian Spirituality: the Good Shepherd

|

| Christ the Good Shepherd. (3rd C). Catacomb Fresco. |

The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.

He makes me lie down in green pastures;

he leads me beside still waters;

he restores my soul.

He leads me in right paths

for his name’s sake.

Even though I walk through the darkest valley,

I fear no evil; for you are with me;

your rod and your staff—

they comfort me.

You prepare a table before me

in the presence of my enemies;

you anoint my head with oil;

my cup overflows.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me

all the days of my life,

and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord

my whole life long.

Psalm 23 probes the spiritual dimensions we find in art: human inwardness, transcendence of life and death, connection with forces of creation. You may be surprised to find the familiar King James formulation, “valley of the shadow of death,” missing. Modern translations don’t use it. Hebrew scripture offered a more ambiguous vision of the afterlife than does the New Testament. Still, the spiritual images of trust in communion with God are unmistakable.

Gerard Manley Hopkins: an Epiphany of Creation

OK, are you ready to return to “The Windhover”? As we tackle this poem, let’s understand that its difficulty reflects the poet’s view of faith, his lifelong struggle with sustaining his faith.

To Christ our Lord

I caught this morning morning’s minion,[1] king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin,[2] dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon,[3] in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein[4] of a wimpling[5] wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend:[6] the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valor and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier![7]

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion[8]

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall[9] themselves, and gash gold-vermilion.

[1] Minion: in medieval times, a loyal servant or a loved one

[2] Dauphin: French feudal title roughly synonymous with prince, the heir to the throne

[3] Falcon: a Windhover is a kestrel or small falcon, a bird of prey

[4] Rung upon the rein: a not particularly precise phrase which nevertheless suggests spiraling flight turning on the wing as a horse might be drawn in a circle by a trainer’s bridle

[5] Wimpling: a wimple is cloth headdress worn by nuns and, in medieval times, by modest married women. Wimpling refers to the undulations and rippling corresponding to a wimple’s folds. Thus air pressure causes the windhover’s wings to ripple.

[6] a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: another image of controlled, arcing movement, a skater arcing on the ice

[7] Chevallier: French for knight, a horseman devoted to a noble cause

[8] Plough down sillion: in this poem, Hopkins revived an archaic word, sillion, referring to the furrow left by a plough.

[9] Gall: harass, trouble, chafe, exasperate

Our footnotes—glosses—testify to the poem’s elusiveness. Yet it’s not that hard to grasp. Lines 1-11 paint a vivid picture, a falcon’s majesty, wheeling, soaring in flight, linked rhetorically to royal splendor. The poet, his “heart in hiding,” is stirred, inspired by the “achieve of, the mastery of” the bird’s aeronautical skill, testimony to the so easily missed glory of God.

In the final lines, we are stirred by Hopkins’ theme, divine glory in unexpected places. A ploughman follows a horse in a “shéer plod.” Yet, in the turned up clay, the plough leaves behind a flashing, multi-colored sheen. As a wood fire burns down, its apparently “blue-bleak” embers ever so briefly gash themselves into God’s “gold-vermilion” splendor.

Hopkins challenges us by honoring and also deviating from traditional Sonnet structure. All the lines of the Octave end in the same Rhyme: A-A-A-A, A-A-A-A. The lines of the Sestet rhyme B-C-B-C-B-C. But the stnzaic boundaries defined by Rhyme clash with apparently random line breaks, the Sestet split in. The Turn occurs in mid-sestet, after line 11, with the last theme of plough and fire playing out over three separate lines. Even words are fractured, split between lines with half a word serving as the rhyme. All of this complicates the form we expect and keeps us on our toes. Unexpected breaks stop us and force us to pay attention.

Hopkins’ play with Meter fascinates lovers of muscular poetry. But the poem is also rich in Figures of Speech. Notice especially the Alliteration: morning morning’s minion; –dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn ; rung upon the rein . Hopkins used the term sprung rhythm to designate his attempt to break the bonds of meter through “ writing and scanning by number of stresses rather than by counting syllables (Hopkins, Gerard Manley). Syllables spill over the meter just as a jazz musician strays outside the metrical norm with an “excess” flourish of notes. The syllables in italics pile up, overflowing the meter like Louis Armstrong’s trumpet riffs. The falcon, prince of the morning, holds an arc against the wind, tethered to a single rippling wing, Hopkins’ verse similarly wheels beyond and then back into meter. Some religious art stirs us, not with the ease of its pieties, but by challenges that call us to walk tightropes of faith.

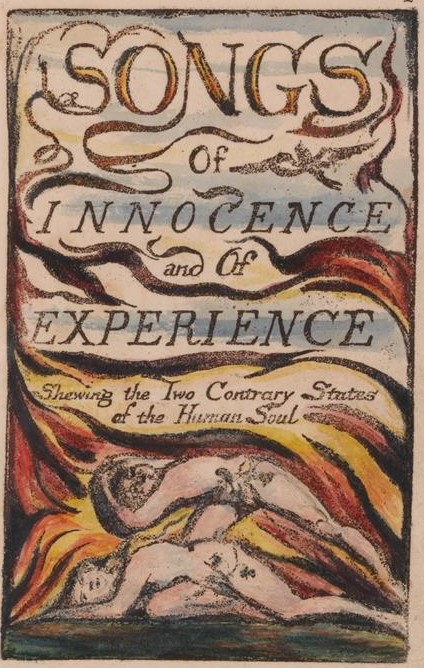

Neo-Christian Romanticism: William Blake

Hopkins’ verse is hard to read and grasp. But its themes are congenial enough to those who share his Christian faith. But how does one read a poet whose spirituality challenges?

William Blake

Poet, prophet, painter, and engraver, [William Blake’s] … poetry and painting were inspired by a prophetic tradition of liberty which looked to the models provided by Milton and the Bible but more fundamentally drew deeply on a popular tradition of Dissent. Blake’s family provided him with a background of religious nonconformity, although its specific nature is unclear (Mee).

|

| Blake, William. (1794). The Ancient of Days. Frontispiece. Europe, a Prophecy. Relief etching with watercolor. |

In the Frontispiece of Europe, a Prophecy, Blake fuses verse with engraving. Most of his poetry was published in illuminated books which he designed and printed at his own cost. Blake’s unforgettable image of Jehovah can be seen as a conventional homage to the Judeo-Christian God. But notice the geometrical angle projected by those split, creating fingers. Blake was fascinated by physicist Isaac Newton’s mathematical model of gravity and the motions of the stars. His image of Jehovah emphasizes the mathematical precision of creation.

But Blake’s Jehovah was also appalled by what he saw as an unhealthy, unbalanced obsession with Reason that suppressed the imagination and other human energies. This Creator’s hand may measure the heavens with a surveyor’s calipers, but the light penetrating cosmic gloom is fired by passion and imagination.

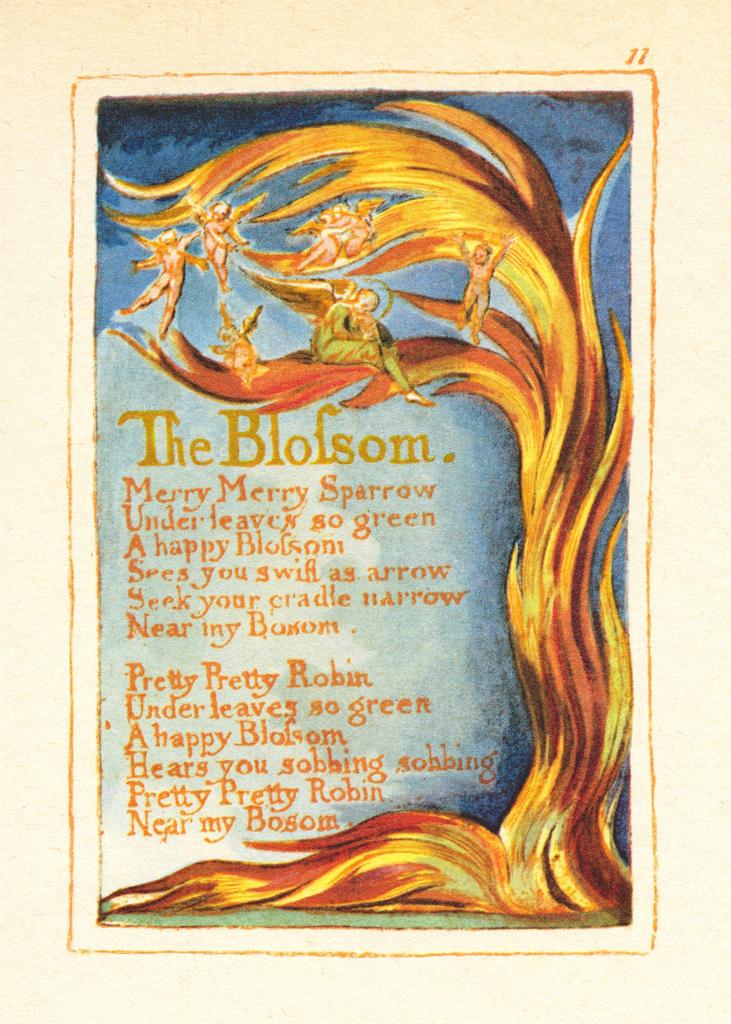

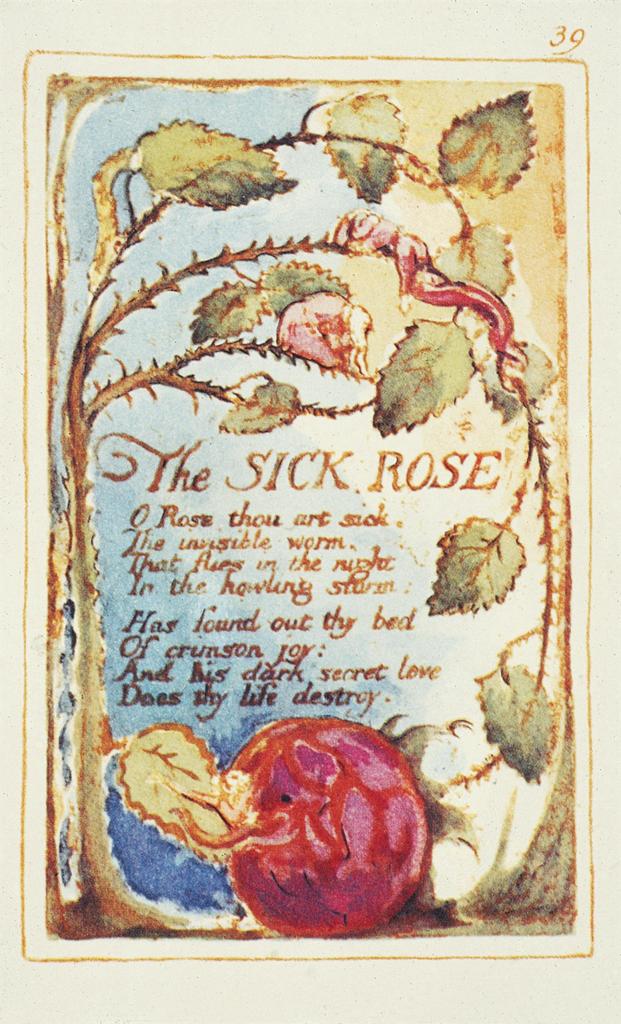

In 1795, Blake self-published Songs of Innocence and of Experience: Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul, This collection pairs poems that probe polar opposites in “Blake’s vision of the interdependence of good and evil, of energy and restraint, of desire and frustration. They range from straightforward, if highly provocative, attacks on unnatural restraint … to extraordinary lyric intensity” (Songs of Innocence). Let’s sample two paired poems from the collection. “The Blossom” cheerily celebrates God’s creation. “The Sick Rose” worries at the sickness at Nature’s core: death.

William Blake (1795) Songs of Innocence and Experience.

|

|

|

| Title Plate. | The Blossom. | The Sick Rose. |

MERRY, merry sparrow!

Under leaves so green,

A happy blossom

Sees you, swift as arrow,

Seek your cradle narrow

Near my bosom.

Pretty, pretty robin!

Under leaves so green,

A happy blossom

Hears you sobbing, sobbing,

Pretty, pretty robin,

Near my bosom.

A very pretty poem and sentiment, almost suggestive of a hallmark card, as long as we don’t notice the Irony and the grief hiding behind the lovely surface. Now compare Blake’s alternate version of nature:

O ROSE, thou art sick!

The invisible worm,

That flies in the night,

In the howling storm,

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy;

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

OK, what does it mean to say the rose is sick? Is it infested by pests? Perhaps. Yet the “invisible worm” is shared by all living things: mortality which always coils with the passions that give life doomed to perish. In the two poems, Blake opposes both sides of life, the joy of youth’s abundance and the specter that forever haunts us.

Christians may be a bit uncomfortable with Blake’s bold, dissenting models of faith. We can, however, approach Blake as an artist imaging and voicing universal spiritual themes of life and death, creation and destruction, freedom and restraint.

William Butler Yeats: a Spiritual Sojourn

Have you ever struggled with your faith, vacillating between doubt and conviction? If so, you may resonate with William Butler Yeats’ poems. In his early years, he toyed with ancient Celtic myths. As he aged, traumatized by the horrors of World War I, Yeats restlessly sought peace, developing a private mythology in which human experience cycles between opposite poles. In Week 2, we read one of his Crazy Jane poems, a series of reflections blending bitterness with hopeful wonder. Here is another from the series.

William Butler Yeats. (1932) “Crazy Jane on God”

That lover of a night

Came when he would,

Went in the dawning light

Whether I would or no;

Men come, men go;

All things remain in God.

I had wild Jack for a lover;

Though like a road

That men pass over

My body makes no moan

But sings on:

All things remain in God.

Banners choke the sky;

Men-at-arms tread;

Armored horses neigh

In the narrow pass:

All things remain in God.

Before their eyes a house

That from childhood stood

Uninhabited, ruinous,

Suddenly lit up

From door to top:

All things remain in God.

OK, so how is this poem spiritual? It advocates no religious doctrine or even distinct spiritual concepts.

It does, however, give voice to the sad, spiritual residue left behind after a lifetime of bitter experience. In the poem, Jane’s memories evoke the age-old destiny of women who have throughout time and space known warriors who rape and “wild Jacks” who love passionately before abandoning them. As her age carries her beyond the concerns of passion and desire, she transcends their human vulnerabilities to impassively behold the eternal cycle of love and war. She offers no judgment, no affirmation of belief. In a haunting refrain, she muses on a timeless, implacable truth, “All things remain in God.”

But the poem closes on a startling moment of spiritual grace, a miraculous memory of a sudden eruption of unearthly light in a ruined house. Though he wandered far from the Christianity of his youth, Yeats treasured moments. In his great poem “Vacillation” (1932), he probes through VIII far-ranging stanzas his spiritual ambiguities, doubts, and convictions. In stanza IV he recalls another magical moment of grace, this one remembered from an afternoon in a book shop.

William Butler Yeats (1932). From “Vacillation.”

My fiftieth year had come and gone,

I sat, a solitary man,

In a crowded London shop,

An open book and empty cup

On the marble table-top.

While on the shop and street I gazed

My body of a sudden blazed;

And twenty minutes more or less

It seemed, so great my happiness,

That I was blessed and could bless. …

Some Christians may struggle with Yeats’ decision to turn away from the Church of his baptism. Yet spiritually sensitive people of all perspectives may empathize with the honesty of his struggle to make an authentic choice. Many people, whatever their perspective, can relate to his cycles of faith and doubt and treasure remembered moments of spiritual grace resembling that of Yeats:

And twenty minutes more or less

It seemed, so great my happiness,

That I was blessed and could bless.

References

Blake, W. (1794). The Ancient of Days. Frontispiece. Europe, a Prophecy. [Etching]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490359.

Blake, W. (1789). The Blossom. In Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. https://www.bartleby.com/235/54.html.

Blake, W. (1789). The Sick Rose. In Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. https://www.bartleby.com/235/74.html.

Blake, W. (1794). Songs of Innocence and of Experience: The Blossom. [Etching]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMCADIG_10312187090.

Blake, W. (1789 to 1794). Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Plate 2, Combined Title Page. [Etching]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AYCBAIG_10313604951.

Blake, W. (1789-94). Songs of Innocence and of Experience: The Sick Rose. [Etching]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822001003977.

Blake, William [Article]. (2012). In D. Birch & K. Hooper, (Ed.s), The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-842.

Bray, J. de. (1670). David Playing the Harp [Painting]. Private collection. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:David_Playing_the_Harp_1670_Jan_de_Bray.jpg.

Christ as the Good Shepherd [Fresco]. (3rd century). Good Shepherd Cubiculum of the Donna Velata, ceiling. Rome, Italy: Catacomb of Priscilla. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_10310196962.

Hopkins, G. M. (May 30, 1877). “The Windhover.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Windhover.

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. (2012). [Article]. In D. Birch & K. Hooper, (Ed.s), The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-3719.

Mee, J. (1999). “Blake, William.” [Article]. In I. McCalman, J. Mee, G. Russell, C. Tuite, K. Fullagar, and P. Hardy (Ed.s), An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199245437.001.0001/acref-9780199245437-e-62.

Portrait of Gerard Manley Hopkins [Photograph]. (n.d.). Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GerardManleyHopkins.jpg.

Songs of Innocence [Article]. (2012). Birch, D., and Hooper, K. (Ed.s), The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-7078.

Yeats, W. B. (1932). “Crazy Jane on God.” In Words for Music, Perhaps. https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/crazy-jane-on-the-day-of-judgment/#content.

Yeats, W. B. (1933). “Vacillation.” In The Winding Stair. http://www.csun.edu/~hceng029/yeats/yeatspoems/Vacillation.

A short rhyming lyric poem, usually of fourteen lines of iambic pentameter.

a verse stanza of 3 lines.

a pattern of repeated sounds, usually the final syllable in the ends of verse lines (Rhyme).

a verse stanza of 6 lines.

A shift, often a contrast, between the themes of the opening and closing stanzas in a sonnet.

pattern of measured sound-units recurring more or less regularly in lines of verse (Meter). In English verse, a pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables: e.g. Jack Spratt could eat no fat//his wife could eat no lean.//And so betwixt them both, you see,//The licked the platter clean.

forms of expression that manipulate normal usage for rhetorical effect. Loosely divided into Tropes (plays of meaning) and Schemes (arrangements and patterns that enhance meaning).

The repetition of the same sounds—usually initial consonants of words…—in any sequence of words: e.g. Tennyson’s ode “To Virgil” (1882) “Landscape-lover, lord of language” (Alliteration).

“a subtly humorous perception of inconsistency, in which an apparently straightforward statement or event is undermined by its context so as to give it a very different significance” (Irony). Pervasive in daily conversation: e.g. Sure, I fully intended to wrap my car around that tree.