Classical Culture in Greece

Catalogues of colleges and universities have traditionally listed Classics as a course of study. In the European educational tradition, Classics referred to ancient Greece and Rome: their languages, histories, literatures, and arts which permeate “Western” culture. Euro-American cultures were exported from Europe, which developed from vestigial Roman culture preserved in the Roman Catholic Church. Roman culture itself was shaped by the influence of Greek mercantile colonies. All Western cultural roads lead back to Greece.[1]

[1] Of course, the cultural situations are much more complicated than this sketch suggests. Whether we speak of Germanic tribes fusing with vestiges of Empire in Western Europe or Spanish, French, or English colonists being re-invented through contact with the indigenous peoples of the Americas, intercultural influences move in both directions.

Greek Art: Archaic Period

Surrounded by the Mediterranean, Greeks took to the sea, cultivating trading relationships with nearby peoples. From the Phoenicians, Greeks learned maritime trade techniques and how to write with a phonetic alphabet. Greek culture was especially influenced by the sophisticated culture of the Nile, Egyptian myths, thought, technology, and art.

| Kouros figure. (6th C. BCE). Attributed to Myron | Kore figure, Lady of Auxerre. (c. 630 BCE). Incised limestone, originally painted. |

We can see the impact of Egypt in the artistic styles of what scholars call Greek’s Archaic era. Votive[2] figures from this time are clearly influenced by Egyptian models. Notice how the Kouros and Kore figures emulate Egyptian statuary: the timeless stance, the abstract, stylized features, and the vacant smiles.[3]

[2] Votive: a gift offered to honor a god and used within a worship ritual.

[3] In the hair and fixed smile of these figures, we also see the influence of Mesopotamian cultures. No time here for that tale!

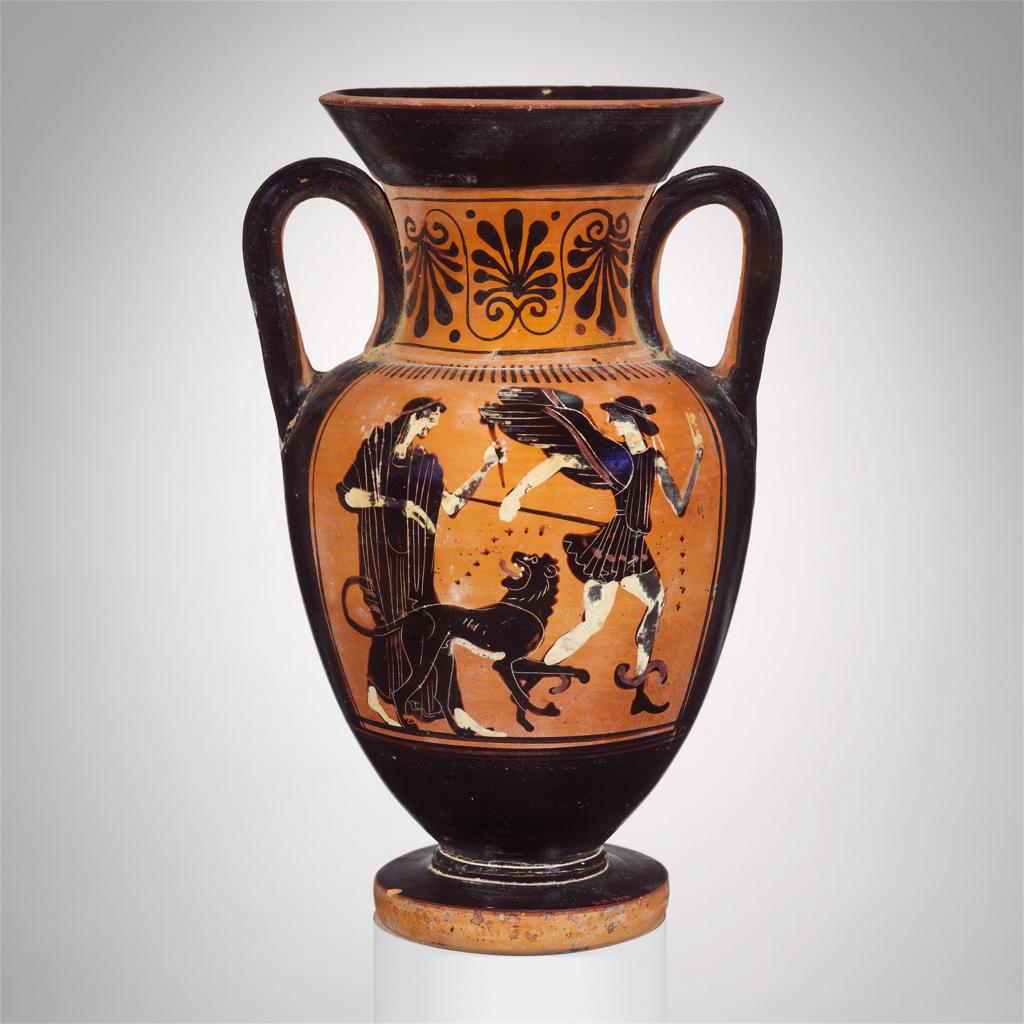

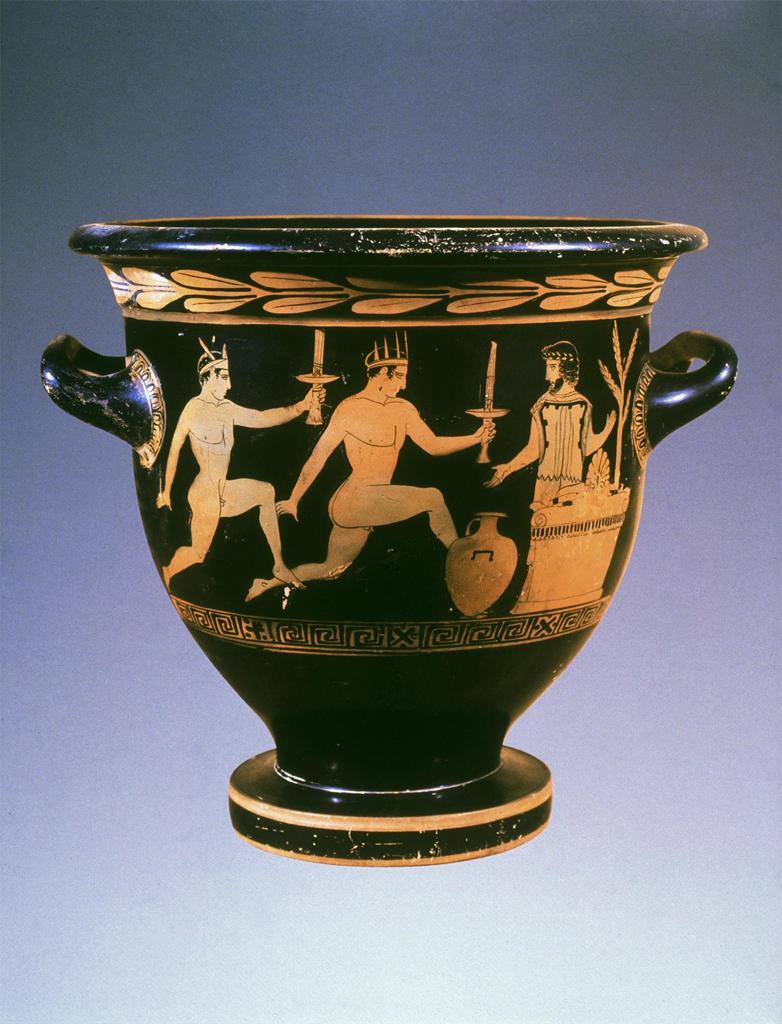

Then Greek artists began to innovate. Red and Black figure vases and amphorae of the 6th and 5th Centuries depicted scenes from daily life and heroic athletes and warriors. Remarkably, the figures are depicted in motion. Greek art was coming alive.

|

|

| Diosphos Painter (c. 500 B.C.), Black-figure amphora (jar) | Peleus Painter. (c.430BCE) Red-figure pottery: Bell-Krater with Torch-racers and Priest at Altar |

- Black Figure Vases: originating in Corinth in the 7th century BCE, in which figures were painted in black silhouette on the light red clay background. Details were added by incising through the black pigment or sometimes by overpainting in red or white (Black-figure vase painting)

- Red figure vases: background painted black, leaving figures in the unpainted red color of the pottery. Details added with a brush rather than incised through the black paint, allowing much greater flexibility and subtlety of treatment. Because of this advantage the red-figure technique, which developed in Athens from about 530 BCE, gradually superseded the black-figure technique (Red-figure vase painting ).

It may not seem remarkable today, but the fact that those black and red figure potters depicted action marked a profound change in artistic possibilities. These figures began to challenge viewers in a new way, forcing them to consider visual experience itself.

The Classical Period

In the 5th and 4th Centuries, Greek dominance over the Mediterranean reached its peak. Trade colonies were established across the Mediterranean: Asia Minor, North Africa, Italy, southern France, and Spain. Beyond economic and political dominance, Greek culture achieved an almost unprecedented level of influence. Rome, for example, emulated Greek culture as it began to develop its power base. The entire Mediterranean world was dazzled by astonishing achievements in philosophy, medicine, geography, history, mathematics, democracy and the arts that shaped the Western world.

|

| Map of Greek and Phoenician trading settlements in the Mediterranean |

Now, “Greece” at the time was far from one fused entity. Ancient Greek culture was defined by a shared mythic tradition and language. Barbarians were those who spoke no Greek, despised by Greek speakers for growling bar, bar, bar, bar. Greek-speaking peoples clustered in city states, each polis competing with and sometimes warring with one another. Among these city states the polis of Athens reached a so-called “Golden Age” under the leadership of Pericles. Athens boasted magnificent architecture, especially on the Acropolis. The Parthenon, temple to Athena, Goddess of wisdom and patroness of the city, was a triumph of order and harmony. It also achieved a technological breakthrough for the day: roof trusses spanned much wider spaces between pillars than did those of Egyptian temples.

|

|

| Acropolis, general view. Athens, Greece | Parthenon. (447-436 B.C). Exterior, west end. Athens, Greece (Acropolis) |

What do you see in the Parthenon? The columns? The pediment, that gable spanning the tops of the columns? Where have you seen these before? In the White House. The Securities and Exchange building on Wall Street. Neo-classical homes in your neighborhood. Inspiring architects into our own day, the look of the Parthenon well earns the term Classical.

On a smaller scale, Greek artists innovated exciting new forms in painting and sculpture. Sadly, apart from a few remarkable sculptures, few of these pieces have survived the erosion of time. Their reputations and theories, however, have endured.

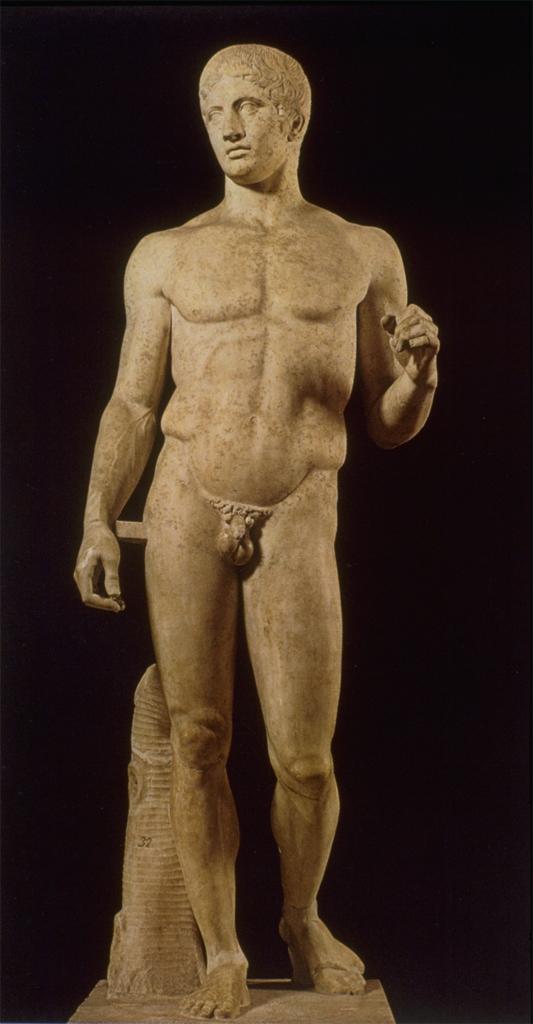

Mimesis refers to the imitation of nature. In the sculptures below, we see unprecedented levels of anatomical precision in presenting the structures of the human body. Greek philosophers and historians were fascinated by empirical observation. Greek sculpture reflects that orientation in its meticulous attention to the form and movement of muscles, skin, and bones. Consider the mimetic naturalism of the musculature depicted in the Spear Carrier (Doryphoros). But consider as well the figure’s stance and its suggestion of movement:

|

|

| Doryphoros [Spear Bearer]. (ca. 450-440 B.C.E.). Roman marble copy of original bronze | Diskobolos [Discus Thrower]. (Bronze original c. 450 BCE; marble copy c. 2nd century CE) |

In classical sculpture, figures come vitally alive. Precisely modeled human forms suggest movement in time and express moods and attitudes.

Let’s see. Mimetic precision. Does that mean portraiture? Well, no. Classical art sought to depict, not a human being but the human being. Theirs was an art not of the real but of the Ideal: “Classical sculpture is idealized, utilizing systems of proportions, balance, and expression that bring order, serenity, and completeness to the figure” (Silberman, Stansbury-O’Donnell, Rhodes). We use the word ideal pretty casually. In ancient Greece, the term derived directly from the work of Plato, a philosopher of incalculable influence. The ideal is …

Classical sculptural figures were formulated to reflect the ideal articulated by the philosopher Socrates in the dialogues of his student, Plato. “Platonic idealism” holds that real objects—a basket, a wagon, a horse, a man—are imperfect reflections of an ideal form beyond our experience: the perfect basket, wagon, horse, man. Classical Greek artists meticulously represented human anatomy, but they sought an ideal beauty beyond ordinary mortals: purity of line, balance, harmony, proportion.

The figure of the Spear Carrier above is perfectly proportioned according to precisely calculated formulas of beauty: facial features, skeletal structure, musculature, etc. This ideal appearance continues to influence our idea of personal beauty even today, sometimes to the detriment of people’s self-image and mental health. The Spear Carrier is also, as I am sure you have noticed, nude. Attitudes of the Greeks toward the body differed from those of neighboring cultures. A key building in every polis was a palaestra, that is, a gym. Athletic workouts and competitions (e.g. the Olympics) were always performed in the nude. When a palaestra was established in a conquered city, the nudity often offended the conquered people. This was one of the reasons for the Jewish revolt against Seleucid (Greek) rule.[4] Idealizing the male body, arts naturally presented them in the nude.

[4] This was the Maccabean Revolt in the 2nd Century before Christ.

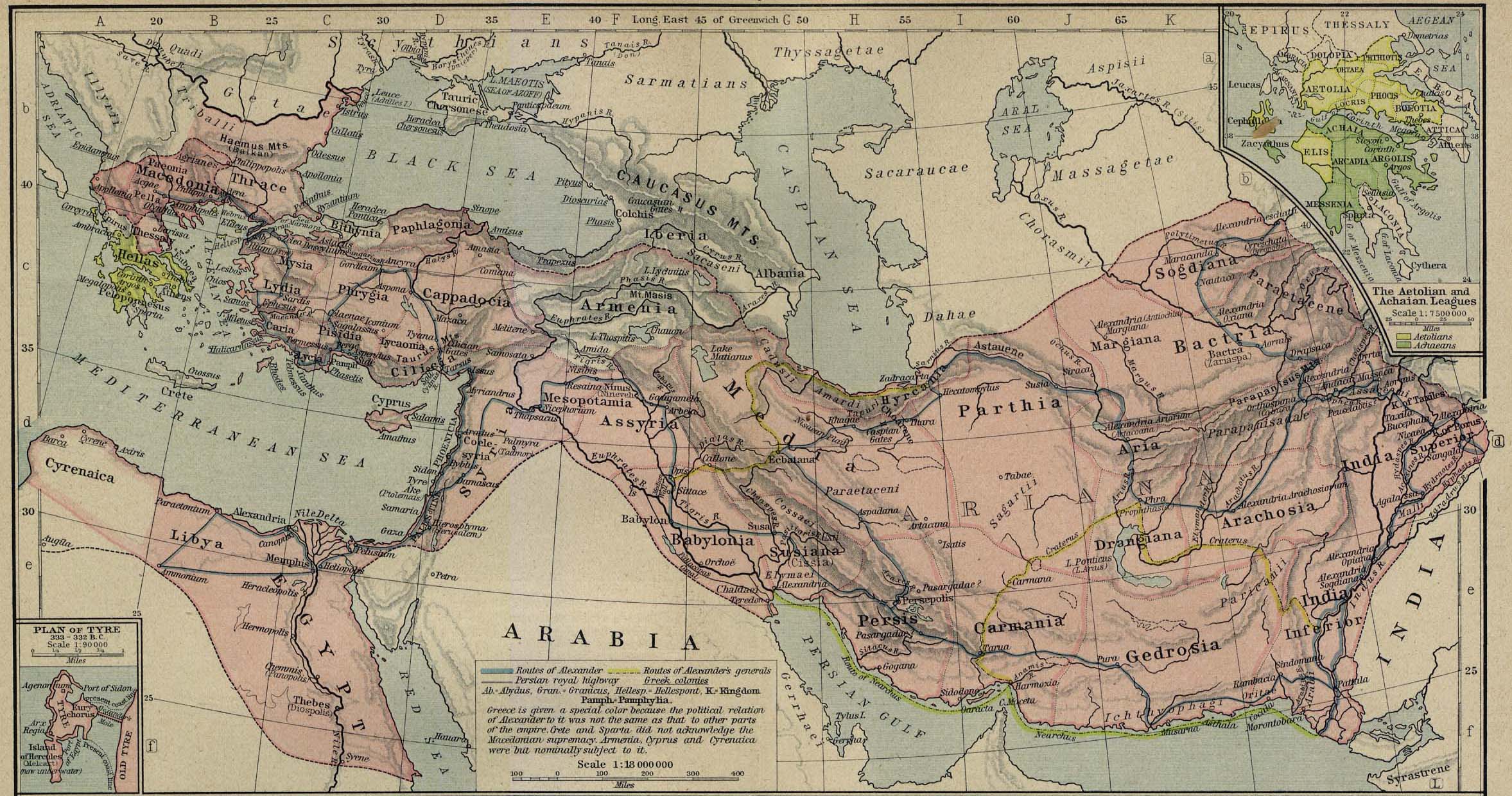

Hellenistic Art

In the 4th Century BCE, the Macedonian/Greek king Alexander the Great avenged Greek peoples for earlier, failed invasions by the Persians and went on to conquer Asia Minor, Palestine, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, and parts of India. After his death, Alexander’s authority descended into regional dynasties: Ptolemaic Egypt and Seleucid Asia Minor, including the Palestine of the New Testament. Hellenistic Greek culture spread from India to North Africa.

|

| Map of Alexander’s Macedonian (Greek) Empire at its greatest extent, bout 336 BCE. |

The traditional distinction between Classical and Hellenistic art is controversial. (Scholars always argue over eras and movements.) Still, enhanced techniques in Hellenistic art master folds of fabric, emotions, and individuality. Shall we see in this movement beyond the ideal a culture losing touch with its classical, golden age or shall we see it as evolution?

Nike: the Personification of Victory

|

|

|

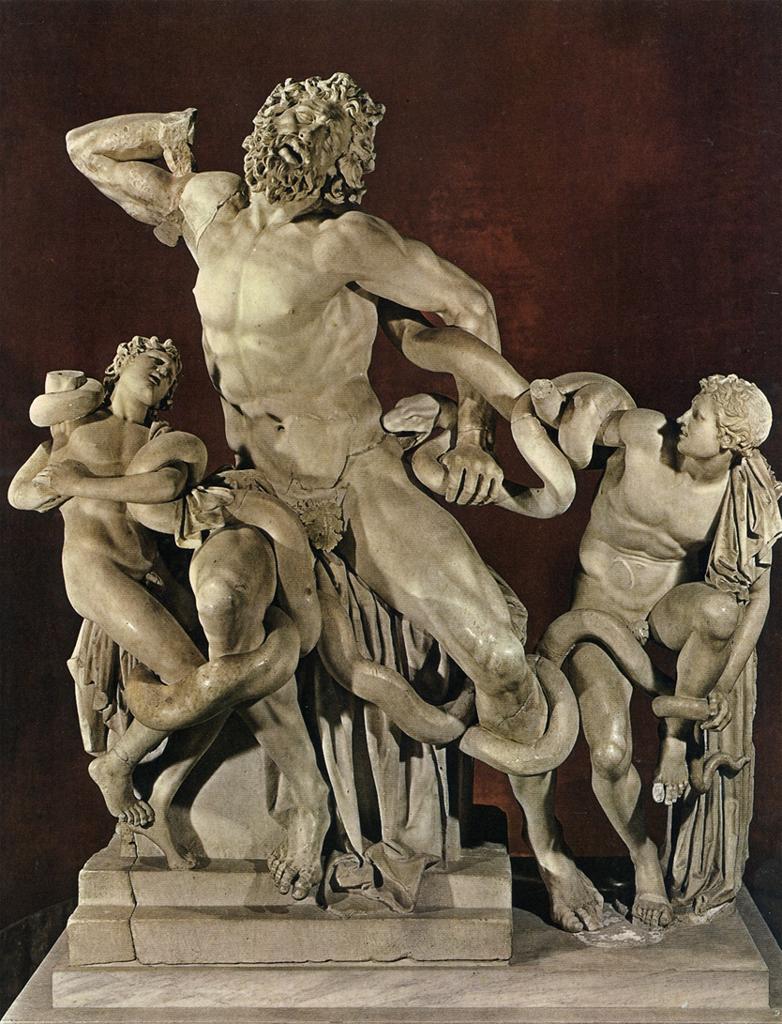

| Nike of Samothrace. (3rd-2nd Century BCE). Marble. | Venus de Milo. (c. 100 BCE). Frontal view. | Laocoön. (50-25 BCE). Marble |

The figure of a half nude Venus discovered in 1820 on the Greek island of Melios (Milos) is one of the most famous images of art on earth. One of very few Greek originals to survive, it is dated today to the 1st Century B.C.E. (Venus de Milo).

The Venus de Milo

Hellenistic art draws on classical conventions, but adds a taste for naturalism, i.e. depiction of the specific features of individuals, as well as a deeper embrace of drama and emotion. We see this in the powerful Laocoön: “A spectacular antique marble group (Vatican Mus.) representing the Trojan priest Laocoön and his two sons being crushed to death by sea serpents as a divine punishment for warning the Trojans against the wooden horse of the Greeks” (Laocoön).[6] The Laocoön‘s intense emotionalism [was] influential on Baroque sculpture, and in the Neoclassical age … [was seen] by Winckelmann,[7] as a supreme symbol of the moral dignity of the tragic hero and the most complete exemplification of the “noble simplicity and calm grandeur” that he regarded as the essence of Greek art and the key to true beauty (Laocoön).

[5] As you will recall, an aesthetic perspective responds to formal aspects of design and sets aside ulterior motives such as, in this case, erotic impulses. Of course, aesthetic perspectives can be hard to maintain and can conflict with some ethical values.

[6] The subject matter of Laocoön testifies to the complexity of Greco-Roman cultures. The story of Laocoön is told in the Aeneid, an epic narrative grafted by the Roman poet Virgil onto Homer’s Greek epic the Iliad. Homer sings of the Greek heroes who conquered the city of Troy. Virgil tells of a Trojan warrior who survives the war and goes on an epic journey leading to the founding of Rome. The poem coopts Greek myth to infuse Rome’s origin story in Greek tradition.

[7]Winckelmann: Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) was a “German art historian and archaeologist, a key figure in the Neoclassical movement and in the development of art history as an intellectual discipline” (Winckelmann).

References

Black-figure vase painting [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-286.

Classical Greek Art and Architecture. [Article] (2012). In Silberman, N. E. (Ed.), The Oxford Companion To Archaeology. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199735785.001.0001/acref-9780199735785-e-0171.

Dickinson, O. T. Ρ. K. (2011). Geometric period. In M. Finkelberg (Ed.), The Homer encyclopedia. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. http://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/wileyhom/geometric_period/0?institutionId=712

Diosphos Painter, attributed to. (ca. 500 B.C.). Terracotta neck-amphora (jar). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11663258.

Dipylon Vase. (8th century B.C.E.). Large funerary krater with scenes of ritual mourning (prothesis) and funeral procession of chariots. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_960032.

Diskobolos [Discus Thrower]. (Bronze original c. 450 BCE; marble copy circa 2nd century CE). Roman copy of a work by Myron. Rome, Italy: National Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_10310840518.

Doryphoros [Spear Bearer]. (ca. 450-440 B.C.E.). Roman marble copy after the original bronze figure. [Sculpture]. Naples, Italy: Museo Archeologico Nazionale. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_970018.

Holberton. P. (2001). “Classicism.” In H. Brigstocke (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001/acref-9780198662037-e-563.

Ideal. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-1192.

Kore figure, known as Lady of Auxerre [Sculpture]. (c. 640-630 BCE). Musée du Louvre. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10311440843.

Kouros figure. Attributed to Myron. [Sculpture]. (6th century BCE). Greece: National Museum of Archaeology. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490474.

Greek and Phoenician Settlements in the Mediterranean, 550 BCE. (1911). In Shepherd, W. R. The Historical Atlas. https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/shepherd/greek_phoenician_550.jpg.

Laocoön. (2003). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press,. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-1343?rskey=y59HDq&result=2.

Laocoön. (50-25 BCE). [Sculpture]. Vatican: Vatican Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31685601.

Macedonian Empire, about 323 BCE. (1911). In Shepherd, W. R. The Historical Atlas. https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/shepherd/macedonian_empire_336_323.jpg.

Osborne, R. (1998) Archaic and Classical Greek Art. New York: Oxford University Press. (Not web accessible).

Parthenon. (447-436 B.C). Exterior, west end. Athens (Acropolis). ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003526546.

Peleus Painter. (c.430-20 B.C). Bell-Krater: Two Torch-racers and Priest at Altar [Vase]. Boston: Arthur M. Sackler Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003065750.

Red-figure vase painting. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-2039.

Rhodes, F. R. (2012). Greek Art and Architecture, Classical. In N. Silberman (Ed.), The Oxford Companion To Archaeology. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 Dec. 2019, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199735785.001.0001/acref-9780199735785-e-0171.

Touchette, L. (2001). Hellenistic art. In Brigstocke, H. (Ed.). The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001/acref-9780198662037-e-1181.

Venus de Milo. (c. 100 BCE). Frontal view. [Sculpture]. Paris, France: Musée du Louvre. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARMNIG_10313261734.

Venus de Milo. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-3625.

Winckelmann, J. J. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-2644#.

the traditional term in European and American academics for a study of ancient Greek and Latin languages and texts.

innovative style of pottery (7th C BCE) in which figures were incised and painted in black silhouette on the light red clay background (Black-figure vase painting). Characterized by human figures portrayed on the move in heroic or domestic action scenes.

innovative style of pottery (6th C BCE) in which the background is painted black, leaving figures in the unpainted red color of the pottery. Details added with a brush rather than incised through the black paint, allowing much greater flexibility and subtlety of treatment. Characterized by human figures portrayed on the move in heroic or domestic action scenes.

in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity. More generally, an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past.

a function of art in which technique imitates nature as closely as possible. Often contrasted with stylized techniques.

a representation, usually in sculpture, of a human figure that approximates the appearance and movements of the real human figure, rather than relying upon a series of more abstract conventions (Silberman, Stansbury-O’Donnell, Rhodes). In Classical Greek sculpture, an unequal distribution of weight on a figure’s legs, emulating the way people actually stand.

in classical Greek art, a naturalistic sense of movement that emulates the the patterns of motion and adjustment in the body in the performance of an action (Silberman, Stansbury-O’Donnell, Rhodes).

the Greek term for emotion. In ancient Greek art, the emulation of human emotion and experience within the appearance of human figures.

a qualification accorded to art which strives to meticulously emulate "the real thing" in nature and reality.

for the classical Greek philosopher Plato, the unchanging and imperceptible Ideas or Forms which all perceptible objects imperfectly copy. In classical Greek art, an attempt to reproduce the best of nature, but also to improve on it, eliminating the inevitable flaws of particular examples through systems of proportions, balance, and expression that bring order, serenity, and completeness (Ideal).