The Baroque: Step Beyond

As Hellenism followed Classical Greek style, so the Baroque follows the Renaissance Renaissance. The word baroque can designate “art of any time or place that shows the qualities of vigorous movement and emotional intensity.” In terms of art history, it specifies 17th Century art especially in Italy, which displays “overt rhetoric and dynamic movement” (Baroque). Baroque painters moved biblical images emphatically into the often sordid environment of gritty Roman streets and cultivated dramatic extremes of emotion.

Caravaggio, the Pope’s Bad Boy

Caravaggio was as famous for his bad boy lifestyle as for his paintings. Yet his sordid life experience powered religious art that fearlessly explored the flashpoint of sin and grace. His gritty biblical scenes are vividly set in the mean streets of Rome. In Calling of St. Matthew, the tax collector disciple (Matthew 9.9) is called away from a gambling table in a Roman tavern.

|

|

|

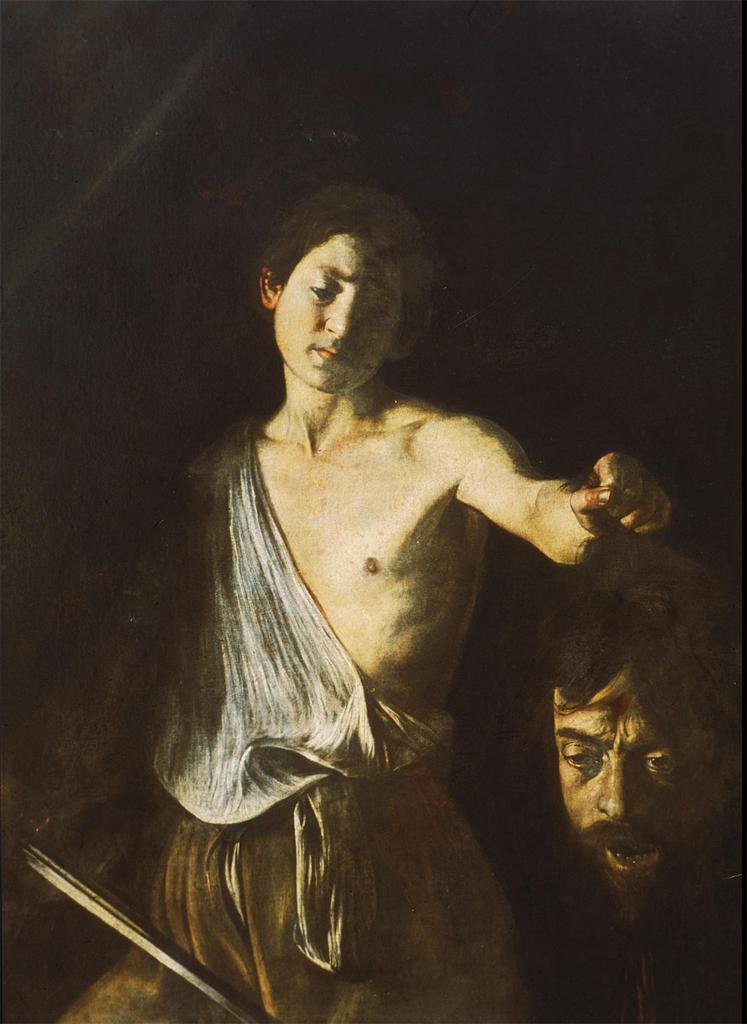

| The Calling of Saint Matthew. (1599-1600). Oil on Canvas. | The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. (ca. 1601-1602). Oil on Canvas. | David & Head of Goliath. (1610). Oil on Canvas. |

The apostle is all too often dismissed as “Doubting Thomas.” Caravaggio’s Thomas, however, is all too human, probing Christ’s living tissues beneath a furrowed brow that intensely seeks truth. Doubt, faith’s other side, engenders an intimate encounter with the incarnate Lord. Caravaggio’s life was steeped in humanity fallibility. After killing a man in a street brawl, Caravaggio was banished from Rome. For years he beseeched the Pope for pardon. As an act of penance, he painted his own face on the head of Goliath held aloft by David. Caravaggio knew how to invest himself in his work!

Caravaggio is particularly renowned for the intense contrasts in his paintings between light and shadow. The term Chiaroscuro has been “used to describe the effects of light and dark in a work of art, particularly when they are strongly contrasting” (Chiaroscuro). Chiaroscuro can be seen in Renaissance works, e.g. Leonardo’s e.g. Virgin of the Rocks, and would feature in artistic media for centuries. In the 1960s, French film theory coined the term Film Noir to describe a cinematic genre found in German Expressionism, French post-war cinema, and Hollywood cinematography of the 1930s and 1940s that used intense contrast between light and shadow for thematic effect. Consider the intensity of the chiaroscuro in Caravaggio’s pieces above.

Dutch Masters

In the 17th Century, the Netherlands commanded the greatest trading fleet and wealthiest trading colonies on earth. Dutch and Flemish merchants patronized some of the most accomplished painters in Europe. While the Italian Baroque was “associated with the Catholic Counter-Reformation,” the Dutch Baroque reflected the Netherlands’ militantly Protestant perspective. Reformed churches repudiated the Catholic veneration of saints, so the Dutch masters focused on contemporary scenes and quiet, domestic scenes (Baroque).

Johannes Vermeer

Johannes (Jan) Vermeer

Vermeer was fascinated by apparently insignificant moments of domestic life. Here, a housewife stands at a window, reading a letter. As is normative in Vermeer’s work, a window in the upper left lights the scene, which is framed by the wall and a curtain.

|

|

|

| Woman reading a letter at window.(ca. 1659). Oil on canvas. | The Milkmaid. (1660).Oil, canvas | Girl with a Pearl Earring. (1665). Oil on canvas. |

Vermeer’s famous painting of The Milkmaid commemorates, not the wealthy homeowner, but a serving woman at her daily chores. The woman is lit from the upper left. Textures of dress, food, and pouring milk are exquisitely rendered and enriched by vibrant, ultramarine blues. In the famous Girl with a Pear Earring, however, the light source is not depicted, although the play of light is carefully delineated. The black background sets off subtle gradations of color and a face expressive of serene personality.

Rembrandt van Rijn

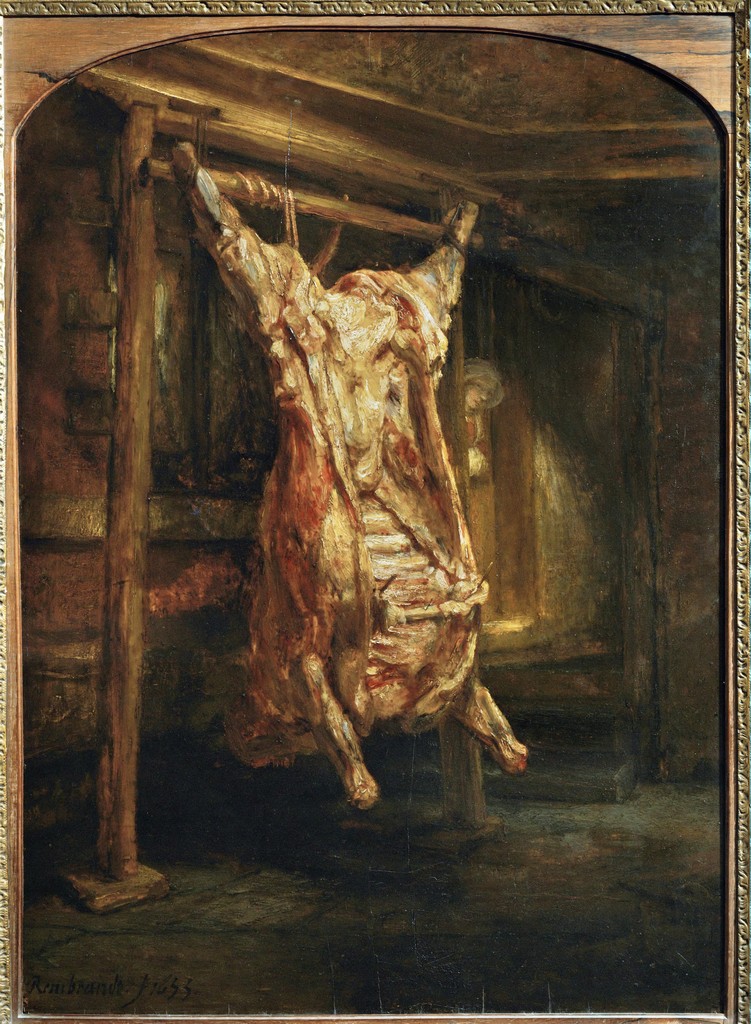

It is not only the quality of Rembrandt’s work that sets him apart from all his Dutch contemporaries, but also its range. Although portraits and religious works bulk largest in his output, he made highly original contributions to other genres, including still-life (The Slaughtered Ox (Rembrandt).

In Rembrandt, we see a powerful culmination of the developments emerging from the Renaissance. The brushwork. The Chiaroscuro. The Linear Perspective. The Foreshortening. And the dramatic intensity that emerged during the Baroque era. There is much to say, for example, about the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, and we will return to it. The scene dramatizes (!) the incident remembered in Matthew 8, Mark 4, and Luke 8 in which Jesus calms a storm terrifying His disciples. Notice how Rembrandt uses zones of light to bring salvation to the men trapped in the darkness of the sea as a destructive element.

|

|

|

| Storm on Sea of Galilee. (1633). Oil on canvas | Slaughtered Ox. (1655). Oil on Panel. | The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch, AKA The Night Watch. (1642). Oil on canvas. |

Fascinated as many painters have been with anatomy, Rembrandt transforms the genre of Still life by picturing the carcass of a slaughtered ox. Rembrandt’s masterpiece, “so discolored with dirty varnish that it looked like a night scene,” was long mislabeled The Night Watch. The painting, over 12 by 14 feet, “showed remarkable originality in making a pictorial drama out of an insignificant event,” the mustering of a company of militia. The great canvas repays long study: “[subordinating] individual portraits to the demands of the composition,” Rembrandt injects an overflowing barrel of life into the scene, dozens of figures, prominent and obscure, caught in individual moments of drama.

References

Baroque. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers , (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-269.

Caravaggio, M. (1599-1600). The Calling of Saint Matthew [Painting]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_1039614343.

Caravaggio, M. (1609-1610). David with the Head of Goliath [Painting]. Rome: Galleria Borghese. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000467199.

Caravaggio, M. (ca. 1601-1602). The Incredulity of Saint Thomas [Painting]. Potsdam, Germany: The New Palace. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_880031.

Langdon, A. (2001). Caravaggio. In Brigstocke, H (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press,. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001/acref-9780198662037-e-464.

Rembrandt. (1642). The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch, known as The Night Watch. [Painting]. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARIJKMUSEUMIG_10313629310.

Rembrandt. (1661). Self-portrait with palette and brushes. London, UK: Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000702900.

Rembrandt. (1633). Storm on Sea of Galilee [Painting]. Boston, MA: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Stolen—whereabouts unknown. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000427318.

Rembrandt. (1655). Slaughtered Ox [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée du Louvre. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10310119770.

Rembrandt. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-2923.

Vermeer, J. (c.1665). Girl with a Pearl Earring [Painting]. The Hague: Mauritshuis. ID 670. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_30941058.

Vermeer, J. (ca. 1660). The Milkmaid [Painting]. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARIJKMUSEUMIG_10313628004.

Vermeer, J. (ca. 1659). Woman reading a letter at the open window [Painting]. Dresden, Germany: GemΣldegalerie. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/LESSING_ART_10310752061.

Vermeer, Johannes [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-3632.

a term for the 17th Century artistic tradition that followed the Renaissance. Characterized by dramatic action, intense passions, chiaroscuro, and gritty social realism. More broadly, art of any time or place that shows the qualities of vigorous movement and emotional intensity (Baroque).

a pervasively influential era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate images and actions in time and space.

a term used to describe the effects of light and dark in a work of art, particularly when they are strongly contrasting (Chiaroscuro). Associated with Baroque painting, but common in the art of the early 20th Century: e.g. German expressionism and film noir cinema.

French for dark cinema, a term coined by 1960s French film critics to describe films with dark themes and black and white film effects that strongly contrasted light and shadow. Characteristic of German Expressionism (1910s and 20s), Hollywood crime films (1930s and 1940s) and French post-war cinema (1940s and 50s).

the illusion of depth in a 2 dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which lines angle toward a vanishing point.

an illusion of depth in a two dimensional image (e.g. a painting) created by contrasting the sizes of objects on the basis of how near or far they are from the eye of the viewer (Foreshortening ).

a genre of painting, drawing, or photograph arranging inanimate objects such as fruit, flowers, pottery or furniture, usually in an interior scene.