Byzantine and Medieval Art: Teaching Christianity

In the century before Christ, Rome displaced the dominance of Seleucid and Ptolemaic Greek empires. Yet Roman culture was largely shaped by Greek influence. For example, Roman art absorbed and emulated Hellenistic models. Indeed, we know many Greek pieces as Roman copies. Scholars still debate whether Laocoön is a Greek original or a Roman copy.[7]

And then came Christianity. Unlike Judaism, Christianity affirms a physical, incarnate God. It reinterpreted the Jewish abhorrence of idolatry to permit images of the Christ. Early Christian art reflected the ethos of small churches that met in private homes and tended to the needs of humble people, especially women and slaves. The Savior was inscribed as a humble shepherd into the walls and ceilings of burial catacombs outside Rome.

|

|

| Christ as the Good Shepherd. (3rd C). Fresco. Catacomb of Priscilla | Christ as the Good Shepherd. (3rd Century). Catacomb of Domitilla. Fresco. |

In the early 4th Century, however, an alliance between the Roman Emperor Constantine changed the world, the church, and Western art. Imperial bishops demanded that all aspects of life, including art, focus on Christian themes. Constantinople, the new imperial capital, honored emperors, Christ, and the Virgin mother in a Byzantine style. In the 6th Century, the Emperor Justinian rebuilt the Cathedral of Constantinople, the seat of imperial church authority. Hagia Sophia (The church of Holy Wisdom) was one of the grandest buildings on earth with the largest dome. It testified to God’s grandeur, but probably more to the power of the Empire that now equated its interests with Christ’s.

|

|

|

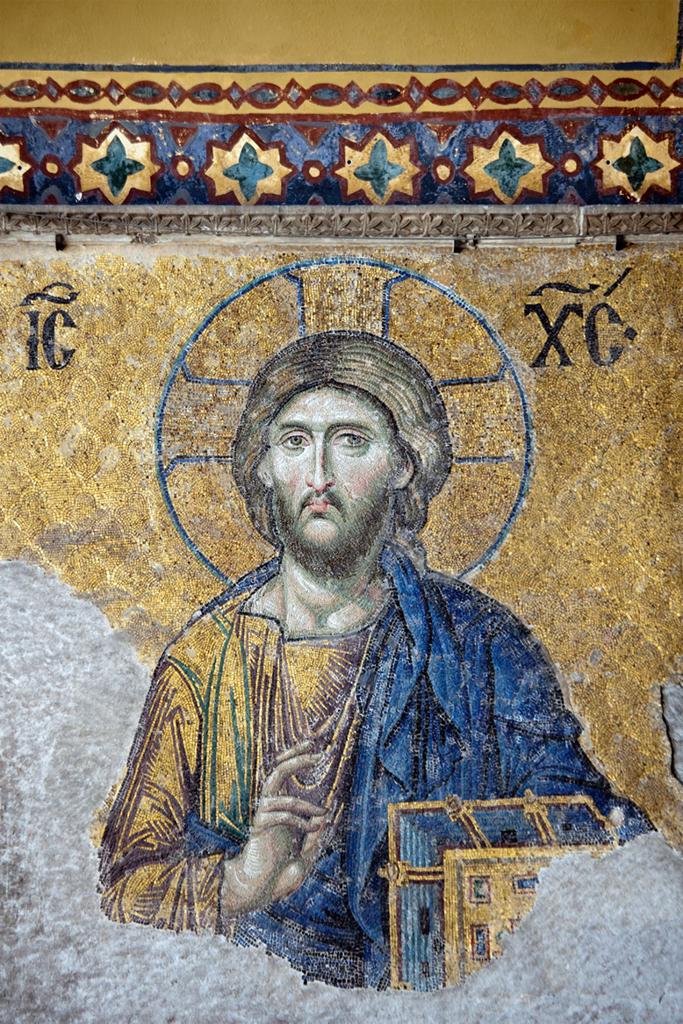

| Hagia Sophia. 6th C. Constantinople (Istanbul, Turkey) | Christ Pantocrator. Mosaic, Hagia Sophia. | Virgin and Child. Mary as Queen of Heaven. Mosaic, Hagia Sophia. |

The interior of Hagia Sophia was ricly decorated with Mosaics:

The mosaics of Hagia Sophia would set the standard for centuries of Byzantine Art throughout the Christianized Empire and Medieval Europe. In a sharp departure from the Classical Greek and Roman Aesthetic, Byzantine artists were constrained by church and empire to focus solely on instructing the faithful in theology and worship. To use a concept from last week, the Byzantine enterprise was a strong example of Didactic Art. An Icon, an image of Christ, the Virgin Mary, or a saint, schooled often believers in the faith and focused their worship of the Lord and their veneration of saints. [8] But Christian faithfulness had also come to mean fidelity to the Empire that had fused with the Church. You can see this fusion in Byzantine images, in which Christ the humble shepherd becomes Christ the emperor, robed in purple, the emperor’s color. Mary becomes Queen of Heaven, her divine child on her lap. As we saw last week, the “Madonna” image was repeated in monumental churches from Asia Minor to the Britain [9].

[8] With little time to explicate the complex issue of veneration of saints, let’s try to summarize it briefly. The Church always condemned worship directed toward anyone but God. However, it encouraged believers to venerate saints who had earned special favor through martyrdom of holy living. Icons (holy images) of the saints and relics from their lives—bones, clothing, possessions—were used for intercessory prayer. The supplicant brought a request to the saint who resided in favor with God in the hope that God would be more likely to grant requests presented by favored saints. Art was deeply involved in these rituals.

[9] The Virgin Mary began to be venerated as the Queen of Heaven as early as the 3rd Century. This designation became a major focus in Medieval Christianity.

Didactic Art generally loses interest in Mimesis and adopts a fixed style. The Stylized art of Byzantine images display little depth. The figures are abstractions with little individuality. They do not move, display little emotion and are not placed in any particular time or place. The image transcends time, including figures from different eras of Christian history. As we saw in Egyptian art, this timeless constancy affirms eternal authority, in this case that of God and the Queen of Heaven.

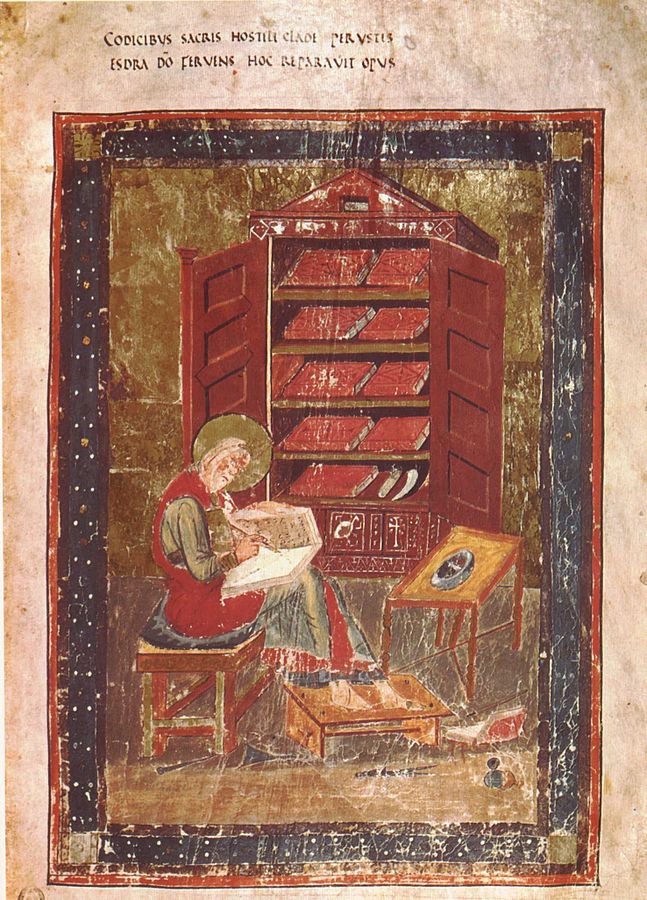

Between the 5th and 7th centuries, Imperial rule in the West—basically, Europe—collapsed in waves of migration from Germanic peoples. Warrior tribal chieftains assumed control of local lands and adopted the titles of the old Empire. But they had little interest in the Classical tradition of learning and art. They converted to Christianity and delegated to monks and bishops the tasks of administration, law, and learning. As knowledge of Greek dissipated, all but a tiny portion of Greek learning was lost to the West for roughly 1,000 years. Church scholars monopolized Latin learning and the churches monopolized art. Anonymous artists designed and decorated churches, created altar pieces for worship, and illustrated Bibles and prayer books.

|

|

|

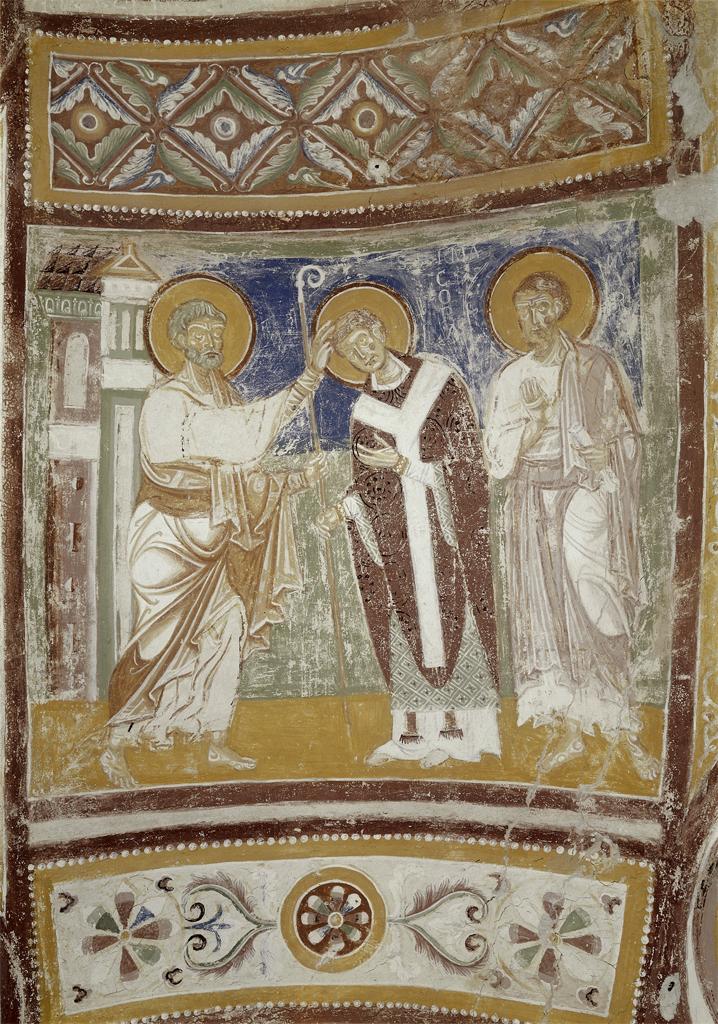

| Ezra the scribe. (7th Century). Book illustration. | Saints Peter, Hermagoras, Fortunatus. (c. 1180). Fresco. | Cimabue. (c. 1290). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter. Tempera on panel. |

For centuries, European artists worked for the church and channeled the standard conventions of Byzantine icons. The image of St. Peter and two later saints affirms the passing of divine authority from generation to generation. As in Byzantine art, it lacks depth of field, mimetic modeling, time, and place. In Medieval Europe, art was almost completely monopolized by the church. Cimabue’s depiction of the Holy Mother and Child was composed in the early the 13th century. Cimabue is working in tempera on wood, not mosaics, but we see that Byzantine style nearly unchanged after a thousand years: flat, expressionless, timeless, and wholly theological. By the 14th Century, European art had strayed very far from its roots in Classical Greece. That was about to change.

References

Christ as the Good Shepherd [Fresco]. (3rd Century). Catacomb of Domitilla. Fresco. Rome, Italy. Wikipedia https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Good_Shepherd_04.jpg.

Christ as the Good Shepherd. [Fresco]. (3rd century). Good Shepherd Cubiculum of the Donna Velata, Rome, Italy: Catacomb of Priscilla. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_10310196962.

Christ Pantocrator. (532-537 CE). Hagia Sophia. [Mosaic]. Istanbul, Turkey: ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ASITESPHOTOIG_10313843105;prevRouteTS=1544900589692.

Ezra the scribe. [Illustration] (692). Folio 5r from the Codex Amiatinus. Florence, Italy: Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS Amiatinus. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CodxAmiatinusFolio5rEzra.jpg.

Hagia Sophia. (532-537 CE). Istanbul, Turkey. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Ayasofya.

Mosaic (2008). [Article]. In Darvill, T. (Ed.). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 8 Dec. 2019, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199534043.001.0001/acref-9780199534043-e-2628.

Virgin and Child [Mosaic]. (532-537 CE). Istanbul, Turkey. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10311442169.

wall or floor decorations made up of many cubes of clay, stone, or glass blocks (tesserae) of different colors. Mosaics may be either geometric, composed of linear patterns or motifs, or figured, with representations of deities, mythological characters, animals, and recognizable objects. Extremely popular in the Greco‐Roman world and Byzantine art (Mosaic).

a style of Christian art developed in the Eastern Roman Empire after the 4th Century to represent Jesus and saints, usually the Virgin Mary, as icons to focus worship and prayer. An “orthodox dogma, serious, other-worldly, conservative style … charged with theological meaning” (Byzantine Art).

in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity. More generally, an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past.

a particular set of values regarding art, taste, and the subjective experience of beauty, ugliness, the sublime, etc. A culture, a school of artists, an individual artist, or an audience can be said to have an aesthetic

art styled in the manner of Byzantine icons: depictions of Christ, the Virgin Mary, or saints in an abstract manner—flat, timeless, emotionless, placeless. Often composed in mosaic, fresco, or paint on panel.

art that is instructive, designed to impart information, advice, or some doctrine of morality or philosophy. The dominant focus of most ancient and Medieval art (didactic).

devotional image of Jesus or the saints from the Byzantine or Orthodox tradition intended to focus worship and prayer with an evocation of “the presence of the saint or mystery” (Icon).

a function of art in which technique imitates nature as closely as possible. Often contrasted with stylized techniques.

figurative visual representation seeking to typify its referent through simplification, exaggeration, or idealization rather than to represent unique characteristics through naturalism (Stylization).