Domestic Art

One could argue that art has always begun in the home. Skilled artists have long been patronized by wealthy families to sumptuously decorate their homes. Indeed, the idea of the Louvre was to provide a venue for wealthy patrons display their personal art collections for the public. Even after institutionalized art museums developed, art has overflowed their walls, disproving the fallacy that art is what museums decide it is. Today, museums account for a small percentage of the vast amount of design that is created and put to use. Art is still overwhelmingly found in the home. Including yours.

Pottery

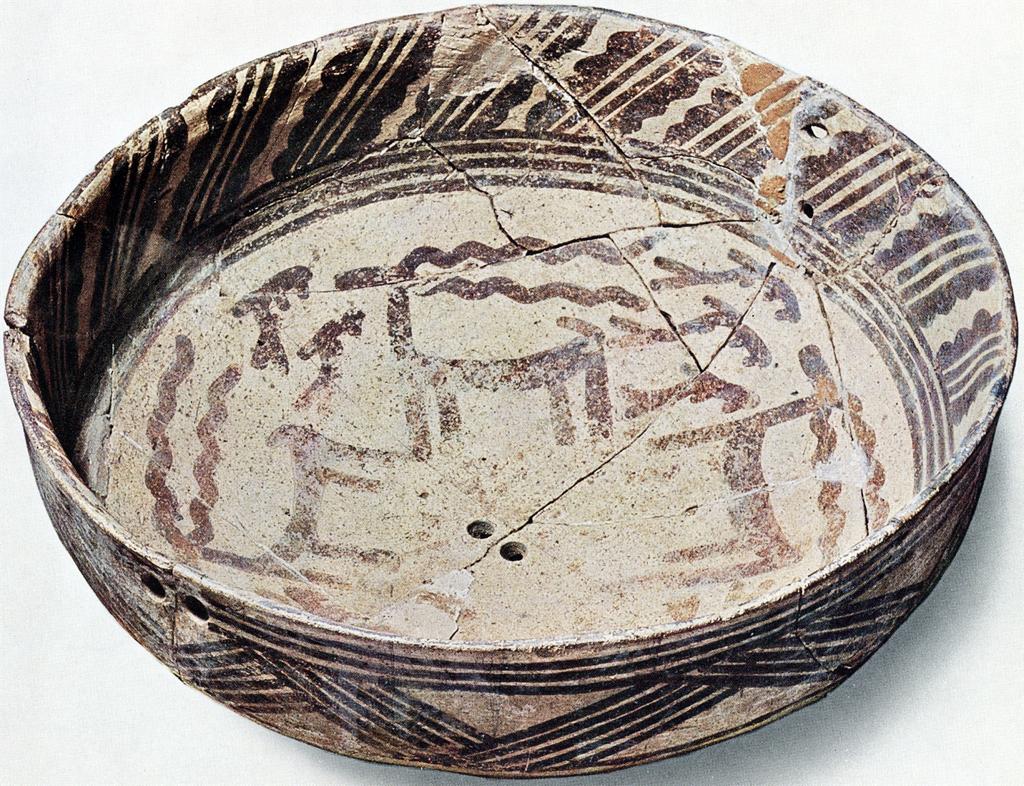

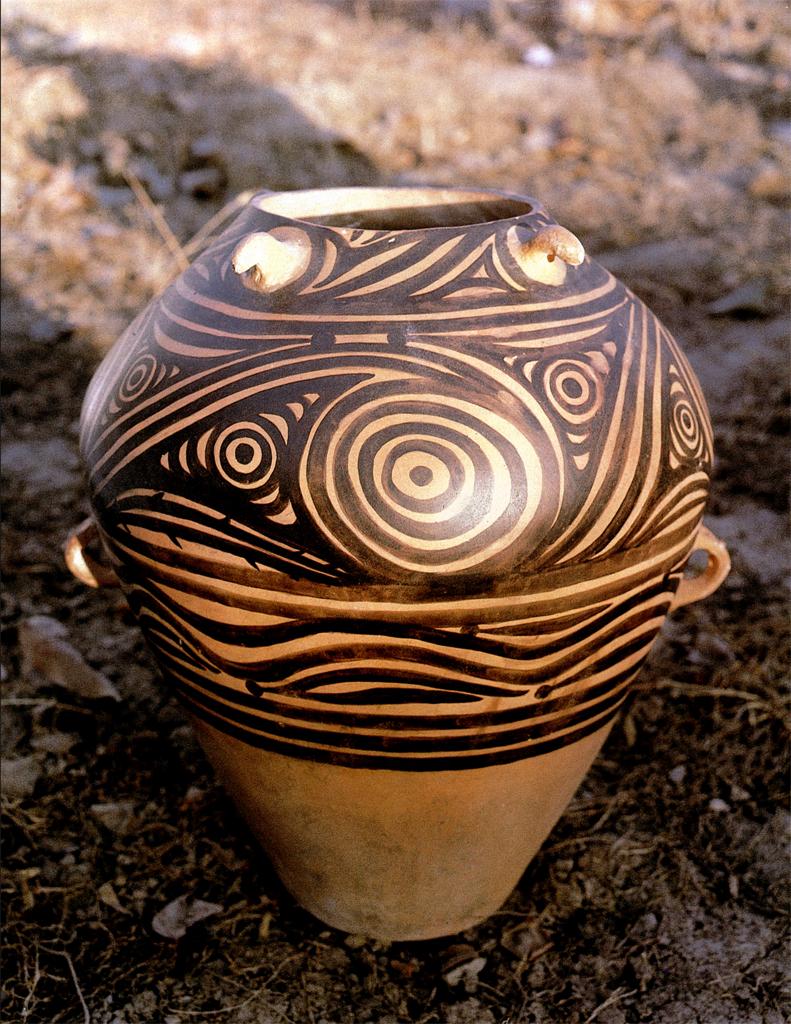

Developed at least 30,000 years ago, pottery—fired clay—was wonderfully useful for collecting grain, fruits, and water. Archaeologists treasure durable pottery for distinctive conventional patterns and techniques that identify prehistoric cultures. Pottery may be useful, but it is invariably enhanced by artistic design. The images below sample characteristic pottery from an array of ancient cultures. You’ll notice some shared conventions, especially animals and geometric design.

|

|

| Horned Animals and Dancers. (Chaleolithic period, c. 5,000 BCE). Ubaid culture, Samarran ceramics. | Jar with Four Ibexes. (Neolithic Pakistan c. 2800-2500 BCE). Jar from “the earliest era of Indian civilization, …the Indus Valley Period,” |

Background information provided by the Artstor site for the Samarran bowl explains key conventions, The most distinctive shapes of Samarran ceramics are deep or shallow bowls, plates, pedestalled bowls and high neck jars. Samarran ceramics are the first in human culture where animal designs were extensively used, and the first to be decorated with human figures. … Swastikas, a common religious symbol in ancient South Asian cultures, appear on the outsides … and whirling, spinning, swirling swastika-like designs are found on the insides. These include gazelles with their horns extended out behind them, females (with three fingers on their hands), with their long hair flying out at right angles to their heads as they spin around, surrounded by designs of scorpions. Similar arrangements of fish, snakes and other life forms are found. The figures are often grouped in fours, with horns or hair at right angles to the main figure in strictly geometrical but swirling pattern.

The venerable Chinese pottery tradition has flourished in China for over 6,000 years. This Hu culture pot exhibits whorls and geometrical patterns that parallel many ancient aesthetics.

|

|

| Pot with swirl pattern. (Hu culture, 4000-2000 BCE) | Porcelain Tang dynasty jar. (618–907 CE): |

Comparing the Hu and Tang culture pieces, can you see the remarkable difference created by a new technology? About 14 centuries ago, Chinese potters made a remarkable technological breakthrough: Porcelain, illustrated in the Tang Dynasty jar above.

Porcelain

A hard, white, translucent ceramic body, which is fired to a high temperature in a kiln to vitrify it. It is normally covered with a glaze and decorated, under the glaze (usually in cobalt), or, after the first firing, over the glaze with enamel colors. … True porcelain was first made by the Chinese in the 7th or 8th century ad, using kaolin (china clay) and petuntse (china stone) (Porcelain).

That sophisticated, high gloss finish characteristic of porcelain lies in the Glaze:

Glazes

A glassy coating on a ceramic body which provides a waterproof covering and a surface for decoration. The ingredients used are similar to those in glass, with a flux added and then ground to produce an insoluble powder. This can then be sprayed or dusted on to a ceramic body. Alternatively, the powder can be mixed with water and the body dipped into this solution. The water is absorbed by the porous body, leaving a coating of glaze, ready to be fired. The glaze is fused to the body after a glost firing, which follows an initial biscuit firing. Earthenware was commonly covered with lead glaze or tin glaze, stoneware with salt glaze, and hard-paste porcelain with feldspathic glaze. Decoration can also be glaze. Decoration can also be applied under the glaze, usually using cobalt, or over the glaze using a wide range of enamel colors. (“Glaze” article)

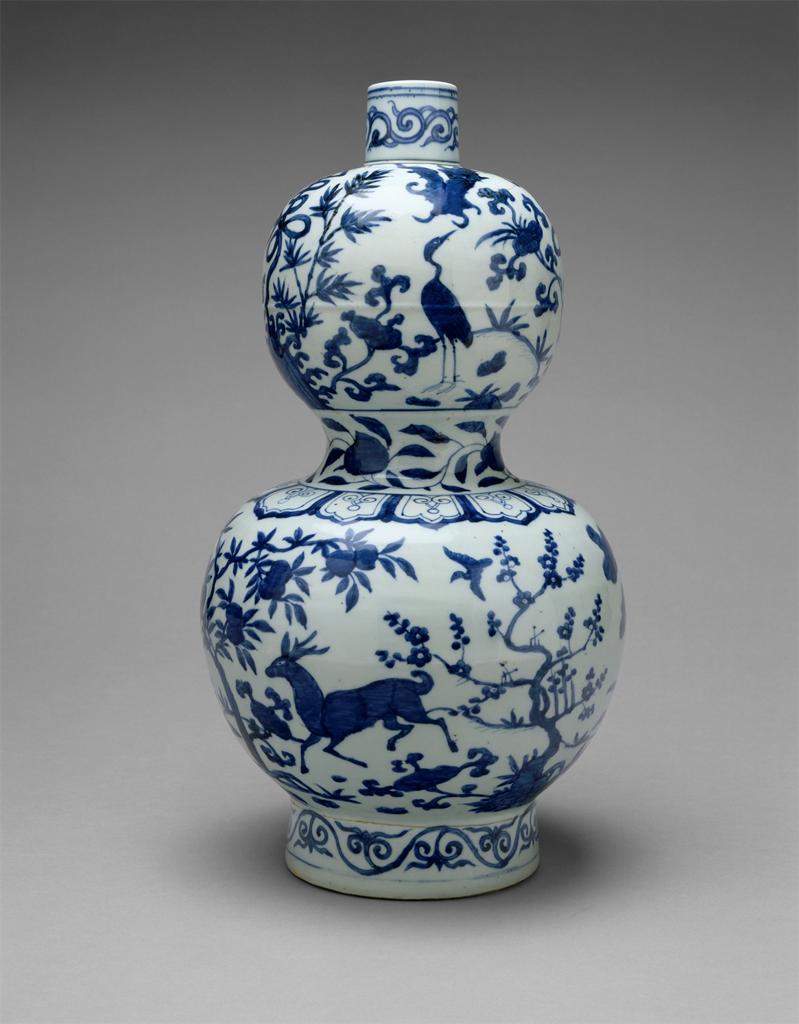

During the Ming Dynasty (16th Century) Chinese porcelain reached a high degree of sophistication using underglazing, “decoration painted on to a ceramic body before the glaze is applied and which is permanently fixed under the glaze when the piece is fired” (“Underglaze”).

In the 17th Century, European mercantile and colonizing efforts dominated trade around the world. A particularly prized import for affluent Europeans was Chinese porcelain, and manufacturers in China tooled up for the export trade (Cinese export porcelain):

|

|

| Ming Dynasty Vase. (1522-66 CE). Porcelain with blue underglaze | Porcelain dish Worcester Porcelain Co. England (1765-1780) |

Of course, import costs raised prices and “there were many attempts to reproduce [porcelain] in Europe” (“Porcelain” article). Chinese techniques proved elusive to European artisans until, in the 18th Century, manufacturers broke through and emulated Chinese designs in bulk production. “China” became a staple of European domestic design and people’s dining rooms.

Carpets, Frescoes, Mosaics

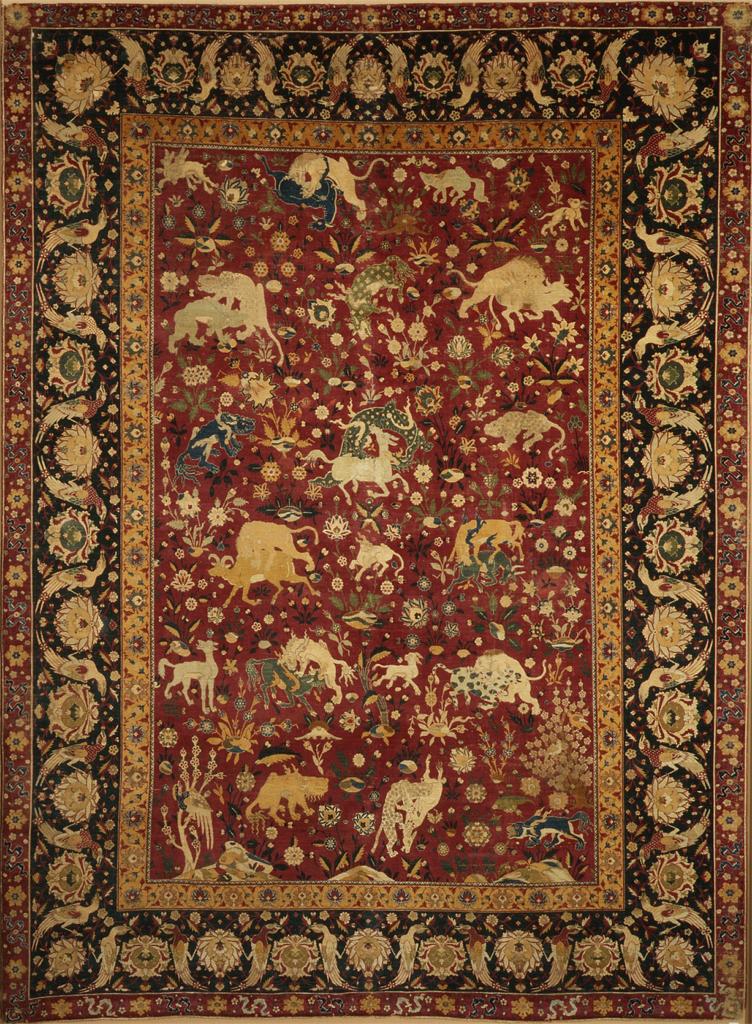

Many cultures express their identity in textiles which, unfortunately, do not survive the passing of centuries as well as pottery does. Often, the designs are abstract with geometrical forms and patterns. For nomadic Islamic cultures of the Middle East, woven carpets provided portable luxury.

The Art of Carpet Weaving

After the conversion to Islam, Arab peoples found themselves influenced by the Hebrew revulsion against idolatry: images of animals and people that could be worshiped as Gods. Thus, although representation of people and beasts is not unknown in Islamic art, it was frowned upon. The glorious tradition of oriental rugs which can be found today in many households worldwide tends toward images of vegetation and abstract designs.

|

|

| Esfahan Herat Rug. (16th century). Persian. Silk warp, cotton weft, wool pile. | Kashan carpet. (16th century). Iranian. Pile weave, silk pile on silk foundation |

Not surprisingly, Middle Eastern carpets were exported to Europe. The distinctive style of the Islamic carpet came to be known in Europe as an Arabesque:

The Arabesque

A distinctive kind of vegetal ornament that flourished in Islamic art from the 10th to the 15th century. The term “arabesque” … is a European, not an Arabic, word dating perhaps from the 15th or 16th century, when Renaissance artists used Islamic designs for book ornament and decorative book bindings. Over the centuries the word has been applied to a wide variety of winding and twining vegetal decoration in art and meandering themes in music, but it properly applies only to Islamic art.

Alois Riegl (1858–1905) was the first to characterize the principal features of the arabesque by noting the geometrization of the stems of the vegetation, the particular vegetal elements used and the fact that these elements can grow unnaturally from one another, rather than branching off from a single continuous stem (Arabesque).

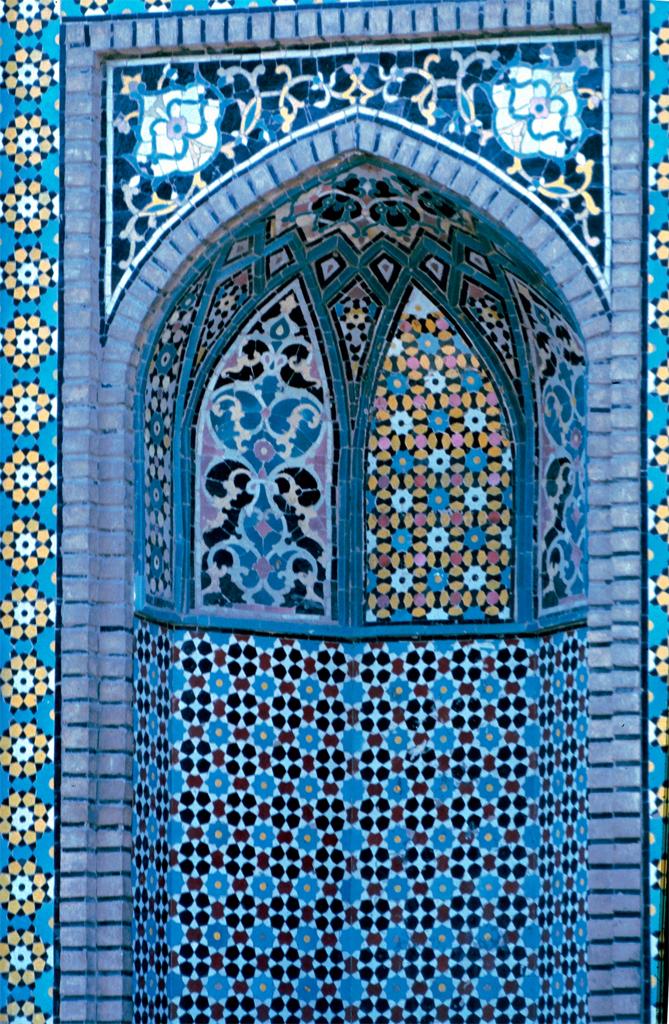

While we must remember that Europeans coined the term, the patterns can be found in many aspects of Arab design, from rugs to decorative ceramics. Arabesques form a key feature of Middle Eastern architecture in palaces and mosques. Often, the effects are achieved with mosaics, as in this detail from an Arab palace.

|

| Arabesques, Fatima’s Haram. (N.D.) Niche: Decorative panels. Qom, Iran. |

In other cultures, domestic design was applied to structures more permanent than a nomad’s tent. Roman villas, for example, were often decorated with Fresco, the ancient version of wallpaper:

Fresco

|

|

| Main salon with garden & birds. (c. 10 BCE-10 AD) Fresco. Prima Porta, Italy: Villa of Livia. | Floor mosaic. (2nd half 4th C. A.D). Taunton: Low Ham Villa. |

As we see in the fresco above, a key function of a villa fresco is to connect the home’s interior and exterior in a time before glass windows were practical. For the floor, house proud aristocrats used Mosaics assembling images from thousands of colored bits of stone. The sample above is from a Romano-British villa home in today’s Taunton, UK. One way the Roman Empire sustained itself was to co-opt local authority figures and reward them with the luxuries of Roman living, including sumptuously designed and decorated villas often equipped with baths.

Asian Silk and Paper Screens

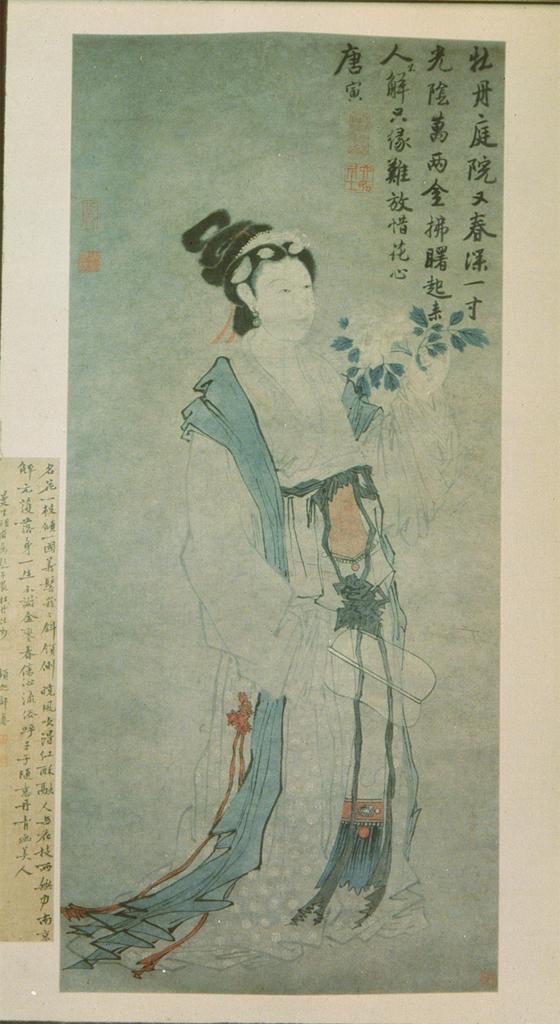

In China and Japan, painted screens of silk or paper divided spaces within the home. Reflecting the close link between calligraphy and art, the screens often combine images with poetic or epigrammatic text. In the work of Yon T’ang (Tang Dynasty, 15th Century CE) we find a fusion of aesthetic dimensions: clothing, architecture, and portals into carefully ordered gardens. Japanese domestic design was influenced by Chinese culture and also by the contingencies of the island. Houses were walled with paper for flexibility and recovery after earthquake.

|

|

|

| Yin T’ang. (1516). Imitation of Tang people. Ink & wash painting. | Yin T’ang Lady with Peony. (16th Century) Paper Scroll | Kunisada. (19th Century) Playing games in an interior overlooking a snow garden. Color Woodcut, ink on paper |

References

Esfahan Herat Rug. [Carpet]. (16th century). Washington, D.C.: Corcoran Gallery of Art, Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ACORCORANIG_10313505788.

Fatima’s Haram. [Niche: Decorative panels]. (N.D.) Qom, Iran. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWADE_10311274994.

Floor mosaic. (2nd half 4th C. A.D). Taunton: Low Ham Villa. Vatican Museum. SSID 13722956. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822001115466.

Guo, X. (1072). Early spring [Painting]. ArtStor. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003468954

Horned Animals and Dancers. [Ceramic]. (c. 5,000 BCE). Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31702369.

Jar with Four Ibexes. (c. 2800-2500 BC). [Ceramic]. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMICO_CL_103803193.

Kashan carpet. (2nd half of the 16th century). [Carpet]. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMICO_METRO_103824828.

Kunisada, U. (19th century). Playing games in an interior overlooking a snow garden. [Woodcut]. New London CT: Shain Library of Japanese Prints. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/CONNASIAN_106310617073.

Li, C. (10th century). Solitary temple amid clearing peaks [Painting]. ArtStor. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000253706

Ming Dynasty Vase [Porcelain]. (1522-66). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/MMA_IAP_10310749391.

Porcelain [Article]. (2010). Clarke, M., & Clarke, D. (Ed.s), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199569922.001.0001/acref-9780199569922-e-1345.

Pot painted with swirl pattern [Ceramic]. (4000-2000 BCE). Sarawak, Malaysia: Chinese History Museum. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/HUNT_57345.

Prima Porta: Villa of Livia: Mural fresco of garden & birds. (c. 10 BCE-10 AD). Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000546794.

Tang dynasty jar [Ceramic]. (A.D. 618–907). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_29394749.

Tang, Y. (ca. 1505-1510). Seeing off a guest on a mountain path [Painting]. Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ, United States. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/APRINCETONIG_10313684971

T’ang, Yin. (1516). Imitation of the Tang people. [Painting]. Retrieved from https://www.wikiart.org/en/tang-yin/-11516.

Underglaze. (2010). [Article]. In M. Clarke & D. Clarke (Ed.s), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199569922.001.0001/acref-9780199569922-e-1724.

Worcester Porcelain Co. [Porcelain]. (1765-1780). Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMICO_CLARK_1039413832.

a hard, white, translucent ceramic body, is fired to a high temperature in a kiln to vitrify it. Normally covered with a glaze and decorated, under the glaze (usually in cobalt), or, after the first firing, over the glaze with enamel colors. First made by the Chinese in the 7th or 8th century CE (“Porcelain”).

a glassy enamel coating on a ceramic body providing a waterproof covering and a surface for decoration applied under or over the glaze (“Glaze”).

a European, not an Arabic, word for a distinctive kind of vegetal ornament that flourished in Islamic art from the 10th to the 15th century. Sometimes applied to winding and twining vegetal decoration in many arts and to meandering themes in music (Arabesque).

primarily an Italian form, a method of wall painting in which powdered pigments dissolved in water are applied to wet, freshly applied plaster, the color being absorbed into the drying plaster as a binding medium (“Fresco”).

wall or floor decorations made up of many cubes of clay, stone, or glass blocks (tesserae) of different colors. Mosaics may be either geometric, composed of linear patterns or motifs, or figured, with representations of deities, mythological characters, animals, and recognizable objects. Extremely popular in the Greco‐Roman world and Byzantine art (Mosaic).