The Art of Love

So art has historically flourished in the home and in the teaching of social, religious, and cultural messages. But I’ll bet that, if you think of poetry, you think first of love.

Domestic Love in Proverbs

As Tolstoy observed in the opening lines of Anna Karenina, some families are happy and some aren’t. Family structures differ enormously in cultures around the world. Poets and artists in these cultures all seem to find a way to celebrate domestic love.

One cultural tradition which has influenced the familial models of many others is that of the ancient Hebrews. Jewish, Christian, and Muslim cultures all look back to the family structure modeled by Abraham, Sarah, and Leah. Abraham’s example was clearly patriarchal, but Hebrew tradition did honor the role of the woman. Centuries after Abraham, the Proverbs writer employs rich poetic rhythms to celebrate the wisdom and strength of an ideal wife.

A wife of noble character who can find?

She is worth far more than rubies.

Her husband has full confidence in her

and lacks nothing of value.

She brings him good, not harm,

all the days of her life.

She selects wool and flax

and works with eager hands. …

She rises while it is still night

and provides food for her household

and tasks for her servant-girls.

She considers a field and buys it;

with the fruit of her hands she plants a vineyard.

She girds herself with strength,

and makes her arms strong.

She perceives that her merchandise is profitable.

Her lamp does not go out at night. …

She opens her hand to the poor,

and reaches out her hands to the needy. …

She makes herself coverings;

her clothing is fine linen and purple. …

She makes linen garments and sells them;

she supplies the merchant with sashes.

Strength and dignity are her clothing,

and she laughs at the time to come.

She opens her mouth with wisdom,

and the teaching of kindness is on her tongue.

She looks well to the ways of her household,

and does not eat the bread of idleness.

Her children rise up and call her happy;

her husband too, and he praises her:

“Many women have done excellently,

but you surpass them all.”

Charm is deceitful, and beauty is vain,

but a woman who fears the Lord is to be praised.

Give her a share in the fruit of her hands,

and let her works praise her in the city gates.

Patriarchal notions of gender relations and of women are deeply rooted in societies that draw on Jewish tradition. However, if we look closely at this Catalogue of wifely virtues, we may be surprised at the characteristics attributed to fine and faithful women: strength, courage, business sense, authority, wisdom, and a resounding voice. Blessed be such women.

Anne Bradstreet’s Great Love

Anne Bradstreet found her way into print by a most improbable route. A child of non-conformist parents, Bradstreet married a man who shared her Puritan convictions and emigrated with him to the new Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. She wrote numerous poems which were published in England in 1650 as a literary marvel. First, it was written in the wilds of the American colonies. And second it was written by a woman, something almost unthinkable in that culture. (For more information on Anne Bradstreet, explore this note: link.) Bradstreet’s most well-known poem is “To My Dear and Loving Husband,” a passionate and loving tribute to the love she and her husband shared.

Anne Bradstreet (1650) “To My Dear and Loving Husband”

If ever two were one, then surely we.

If ever man were loved by wife, then thee.

If ever wife was happy in a man,

Compare with me, ye women, if you can.

I prize thy love more than whole mines of gold,

Or all the riches that the East doth hold.

My love is such that rivers cannot quench,

Nor ought but love from thee give recompense.

Thy love is such I can no way repay;

The heavens reward thee manifold, I pray.

Then while we live, in love let’s so persevere,

That when we live no more, we may live ever.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Reflections on Love

|

| Michele Gordigiani. (1858). Portrait of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Daguerreotype. |

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was hailed as one of the finest poets of the Victorian age, although at the time the praise was generally qualified: one of the finest female poets. In 1846, she was contacted by Robert Browning, a young poet impressed by her work. The two poets were married and enjoyed many years of loving relationship. (For more information on Elizabeth Barrett Browning, explore this note: link.). You may well be familiar with at least the first few lines of this selection from Sonnets from the Portuguese (1844).

Elizabeth Barret Browning. (1844) Sonnet #43

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Browning’s famous sonnet testifies to the great love she shared with her husband. As does Anne Bradstreet, she composes a Catalogue of celebrations, in this case, dimensions of love: soul, freedom, purity, passion, time, faith, and spirit.

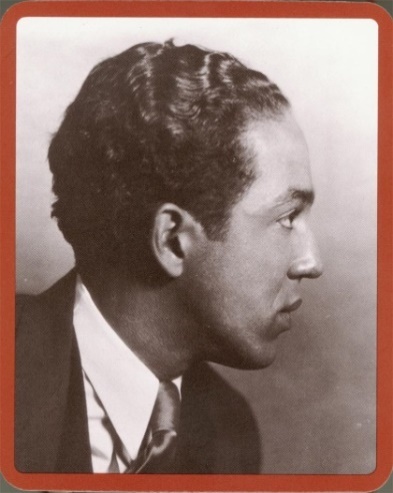

Langston Hughes: Maternal Love

|

| Allen, James L. (1930). Portrait of Langston Hughes. Photograph. |

When we think of domestic love, we often think first of love between spouses. Yet few themes carry more weight than that of a mother for her child. A mother’s steadfast love gains even more power when it stands strong in the face of challenges. In 1902, Langston Hughes was born in Joplin Missouri to a mixed heritage steeped in a tradition of education and ethnic pride. We will meet Hughes again during the course in his role as one of the prominent members of the so-called Harlem Renaissance. (For more information on Langston Hughes, explore this note: link.)

Langston Hughes. (1926). “Mother to Son”

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor—

Bare.

But all the time

I’se been a-climbin’ on,

And reachin’ landin’s,

And turnin’ corners,

And sometimes goin’ in the dark

Where there ain’t been no light.

So boy, don’t you turn back.

Don’t you set down on the steps

’Cause you finds it’s kinder hard.

Don’t you fall now—

For I’se still goin’, honey,

I’se still climbin’,

And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

Hughes’ powerful poem celebrates the steadfastness by which an enduring mother tries to instill courage and perseverance in the mind of a son tempted by waywardness walking the hard road of racist America. This advice takes on extra force when we understand that Hughes’ father, frustrated by America’s hostile environment, emigrated to Mexico, leaving his wife and son behind to make their way. Thinking of our own day, the poem helps people of other ethnicities understand the challenges facing Black parents in raising children in a society that continues to crush their dreams.

Passionate Love

Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth—

for your love is more delightful than wine.

Pleasing is the fragrance of your perfumes;

your name is like perfume poured out.

No wonder the young women love you!

Take me away with you—let us hurry!

Let the king bring me into his chambers.

Recognize these lines? You may or may not be surprised to find that they are excerpted from the opening chapter of The Song of Songs, one of the books of Hebrew wisdom literature (Christian Old Testament).

Song of Songs has often been interpreted as an extended metaphor of God’s love for His church. However, the text clearly celebrates that part part of God’s creation that leads to renewed life. You will not be surprised to note that one of the driving energies of the arts throughout human experience is that of sexual passion. The myth of love as a consuming passion has fueled numerous poetic traditions.

Love in the Elizabethan court

When he wasn’t writing patriotic plays, Shakespeare was engaged in one of the most hotly contested games of the Elizabethan court: composing Courtly Love verses to impress lords and ladies alike. Courtiers competed with each other for top honors in composing love poems of surpassing wit and flattery. Shakespeare was, of course, the master. Reading his sonnet below, ask yourself how he gets the best of his competitors. (For more information on Shakespeare’s poetry, explore this note: link.)

William Shakespeare, Sonnet 130

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;[1]

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked,[2] red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound;

I grant I never saw a goddess go;

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground.

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

[1] In Shakespeare’s day, pure whiteness of skin was considered the highest form of beauty since it was associated with the sheltered lifestyle of a wealthy woman never required to expose herself to the sun. Dun: a sort of mousy-gray brown considered inferior.

[2] Damasked: a patterned blend of colors as in sumptuously woven cloth

Now let’s see. The poem makes ten comparisons. In each, the lover comes off the worse. What sort of flattery is this? Well, for each comparison think of a trite bit of flattery common to lesser wits. My lovers eyes are like the sun! Her lips are red as coral. Her breasts are white as snow. Etc. Shakespeare keeps denying that these fanciful clichés have anything to do with his mistress, whose beauty is of the real world. Of course, the real target of the poem is those lesser courtly wits capable only of “false compare.”

Traditional Ballads

Courtly Love verse was composed for and read by elite levels of society. But ideals of love’s passion are shared at all levels of society. Folk verse, too, was lit by love’s splendor and haunted by its failure. The most common folk genre was the Ballad: “strictly speaking, a story in song” (McNeill). For centuries, ballads were composed, sung, and revised by bards singing in taverns and inns. No one wrote them down, and bards felt free to express their poetic talents in their own versions of popular standards. Thus, no version could be “authoritative.”

In the 16th Century, printers began to sell texts to as many people as possible. McNeill explains the development of broadside ballad: “a ballad printed on a broadside—a single sheet of paper on the early modern printing press—usually eight by twelve inches.” Such broadsides preserved and fixed particular versions of ballad lyrics, some read and sung yet today.

|

| Thomas Rowlandson. (19th Century). The Ballad Singers. Drawing & Watercolor. |

In the 16th Century, printers began to sell texts to as many people as possible. McNeill explains the development of broadside ballad: “a ballad printed on a broadside—a single sheet of paper on the early modern printing press—usually eight by twelve inches.” Such broadsides preserved and fixed particular versions of ballad lyrics, some read and sung yet today.

“The Unquiet Grave” (15th Century?)

“The wind doth blow today, my love,

And a few small drops of rain;

I never had but one true-love,

In cold grave she was lain.

“I’ll do as much for my true-love

As any young man may;

I’ll sit and mourn all at her grave

For a twelvemonth and a day.”

The twelvemonth and a day being up,

The dead began to speak:

“Oh who sits weeping on my grave,

And will not let me sleep?”

“’T is I, my love, sits on your grave,

And will not let you sleep;

For I crave one kiss of your clay-cold lips,

And that is all I seek.”

“You crave one kiss of my clay-cold lips,

But my breath smells earthy strong;

If you have one kiss of my clay-cold lips,

Your time will not be long.

“’T is down in yonder garden green,

Love, where we used to walk,

The finest flower that e’re was seen

Is withered to a stalk.

“The stalk is withered dry, my love,

So will our hearts decay;

So make yourself content, my love,

Till God calls you away.”

Listen to the audio file of Luke Kelly’s performance of the ballad

“The Unquiet Grave” illustrates themes common to traditional ballads. Such songs celebrate heroic ideals of true love, but the challenge in them is very often the perpetual human enemy, death. In folk ballads, lovers are separated by death, but the living lover remains perennially faithful, often loitering about by a gravesite haunted by the spectral voice of the beloved.

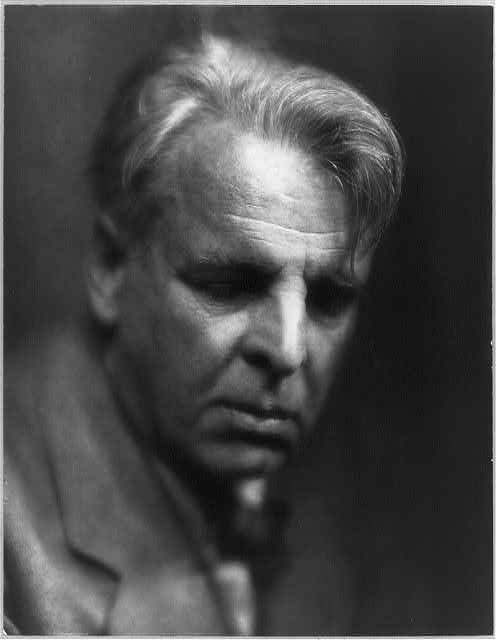

William Butler Yeats, Celtic Troubadour

|

| Portrait of William Butler Yeats. (Feb. 7, 1933) Photographic print |

The Anglo-Irish poet William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) steeped his work in Celtic traditions, contemporary Irish experience and his own reflections on mortality and the heart. At 24, Yeats met Maud Gonne, a powerful woman passionately committed to Irish independence. Yeats fell deeply in love with Gonne and was haunted by her rejection of him. Her aura pervades his verse, often embodied in the apple blossoms he recalled from their first meeting.

William Butler Yeats (1899) “The Song of the Wandering Aengus”

I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in a stream

And caught a little silver trout.

When I had laid it on the floor

I went to blow the fire a-flame,

But something rustled on the floor,

And someone called me by my name:

It had become a glimmering girl

With apple blossom in her hair

Who called me by my name and ran

And faded through the brightening air.

Though I am old with wandering

Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

I will find out where she has gone,

And kiss her lips and take her hands;

And walk among long dappled grass,

And pluck till time and times are done,

The silver apples of the moon,

The golden apples of the sun.

Yeats’ early verse drew heavily on Celtic myths. This poem remembers a Celtic god: “Angus Óg is the god of youth and beauty among the Tuatha Dé Danann; he may also be the god of love, if any such god can be said to exist” (Angus Óg). Yeats finds inspiration in the association of Aengus with poetry and with “a widely known story” of Angus Óg “wasted by longing for a beautiful young woman he has seen only in a dream.”

“Somewhere Beyond the Sea”: Love’s Ideal

|

|

Bobby Darin. (11 March 1959). Publicity photo. |

In post-World War II America, cabaret singers like Bobby Darrin gained enormous popularity. One of his most famous songs casts an idealized vision of love’s impossible promise.

Charles Tenet and Jack Lawrence, (1945) “Beyond the Sea”

Somewhere beyond the sea

somewhere waiting for me

my lover stands on golden sands

and watches the ships that go sailin’

Somewhere beyond the sea

she’s there watching for me

If I could fly like birds on high

then straight to her arms

I’d go sailin’

It’s far beyond the stars

it’s near beyond the moon

I know beyond a doubt

my heart will lead me there soon

We’ll meet beyond the shore

we’ll kiss just as before

Happy we’ll be beyond the sea

and never again I’ll go sailin’

I know beyond a doubt

my heart will lead me there soon

We’ll meet (I know we’ll meet) beyond the shore

We’ll kiss just as before

Happy we’ll be beyond the sea

and never again I’ll go sailin’

No more sailin’

so long sailin’

bye bye sailin’…

Listen to Bobby Darin’s performance of the song.

To an ironically post-modern taste, the song might sound a bit naïve. Still, how naïve is the song, really? Remember that Bobby Darin’s generation had endured a Depression and a World War. Those folks knew plenty about reality. And the fantasy lover is imagined in some unrealizable realm beyond moon and stars, not in the streets of post-war America.

Actually, the core themes of the song drive countless lyrics and dramas as popular as ever today and in many cultures. Romantic comedies. Romance novels. Bollywood musicals. Telenovelas. Valentine’s Day greeting cards. All affirming the dream of passionate true love for “the one” selected by “the universe” to fulfill an otherwise incomplete life. Our tales tell us that passionate completion with one’s fated beloved irradiates life in an explosion of grace.

References

Allen, James L. (1930). Langston Hughes. Photograph. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LOCEON_1039796913

Bobby Darin[Photograph]. (11 March 1959). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bobby_Darin_1959.JPG

Bradstreet, Anne. (1650). “To My Dear and Loving Husband.” In The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America. https://www-fulcrum-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/epubs/cv43nx03m?locale=en#/6/526[xhtml00000263]!/4/1:0

Browning, E. B. (n.d.). Sonnets from the Portuguese 43: How do I love thee me count the ways. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43742/sonnets-from-the-portuguese-43-how-do-i-love-thee-let-me-count-the-ways

Darin, B. (1969). “Beyond the Sea.” [Audio Recording). On Beyond the Sea: the Very Best of Bobby Darin. Warner Brothers. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m8OlDPqYBLw

Hughes, Langston. (1926). “Mother to Son.” In The Weary Blues. New York: Knopf. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47559/mother-to-son

Kelly, L. (2004). The Unquiet Grave. [Audio recording]. On The Best of Luke Kelly. Ireland: Celtic Airs. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jyqBA_Qr3qs

Lawrence, J. and Tenet, C. (1945). “Beyond the Sea.” https://lyricsplayground.com/alpha/songs/b/beyondthesea.html

Shakespeare, W. (1609). Sonnet 18: Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45087/sonnet-18-shall-i-compare-thee-to-a-summers-day

Portrait of William Butler Yeats. (Feb. 7, 1933). Photographic print. Washington, D.C: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. LC-USZ62-87604. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002716129/

Rowlandson, Thomas. (19th Century). The Ballad Singers. Drawing & Watercolor. New Haven CT: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AYCBAIG_10313607036

The Unquiet Grave. (15th Century?) Anonymous. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50403/the-unquiet-grave#poem

Yeats, William Butler. (1899). “The Song of the Wandering Aengus.” In The Wind Among the Reeds. London: Elkin Mathews. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/55687/the-song-of-wandering-aengus

A type of verse that “records the names of several persons, places, or things in the form of a list.” It is “common in epic poetry,” and in the free verse of Walt Whitman.”(Catalogue Verse).

a Resurgence in black culture, also called the New Negro Movement, which took place in the 1920s, primarily in Harlem, but also in major cities. Primarily a literary movement but also a time of achievements in visual art, dance and music. The term invokes a rebirth of African American creativity (Harlem Renaissance).

an idealized conception of passionate love with strong influence from Arab verse and developed among the troubadours in 12th Century Southern France. The “adored lady is modelled on the dependence of feudal follower on his lord; the love itself was a religious passion, ennobling, ever unfulfilled, and ever increasing” (Courtly Love). A conception of sexual love that remains pervasively influential in modern culture and its arts.

a poem or song that tells a story. Often, oral poetic genres compiled anonymously within folklore traditions for audiences of limited literary education.