The High Renaissance

The Renaissance Begins: Masaccio and Fra Angelico, Mantegna

If you would like to see the Renaissance emerging before your eyes, visit Florence, Italy. First, walk up the nave of the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella. Look for an apparently unassuming Fresco in a niche on the left wall: Massacio’s The Holy Trinity. Next, in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Carmine, explore the Brancacci Chapel, which features work by several artists. Study Masaccio’s The Tribute Money, based on the story of Jesus paying his tax by sending Peter to look for a coin in the mouth of a fish (Matthew 17.24-27). Masaccio is following Giotto’s lead in dramatizing bible stories. He places three moments from the story into one pictorial frame with linear perspective creating depth of field.

|

|

|

| Masaccio. (ca. 1427) The Holy Trinity. Niche Fresco. | Masaccio. (ca. 1427). The Tribute Money. Fresco | Fra Angelico. (1428). The Annunciation.Tempera on panel. |

Now step along a few Florentine blocks the the monastery of San Marco in which the monk Fra Angelico continued the exploration of perspective. His Anunciation celebrated the moment of Christ’s conception as a remedy for Adam and Eve’s fall into sin, depicted in the left third of the fresco. Symbolically, Linear Perspective saves the world from sin. That ray of light is the Holy Spirit impregnating Mary with a divine child, Christians’ Savior.

During the early Renaissance, a mania broke out for mathematically precise Linear Perspective. Architecture and landscapes offers the readiest subject matters for lines converging on a vanishing point in a deep distance. However, increasing sophistication in evoking depth of field also enhanced the Mimetic precision of organic objects, including human figures:

We see the dramatic impact of Foreshortening in Mantegna’s remarkable Dead Christ. In this unusual example of the Pieta, the viewer is forced to adopt a perspective confronting the physicality of dead flesh. In religious terms, this perspective compels a somber reflection on Christ’s body of suffering, a major focus for piety of that age. Visually, it calls on viewers to consider the geometry of our visual experience of depth.

|

|

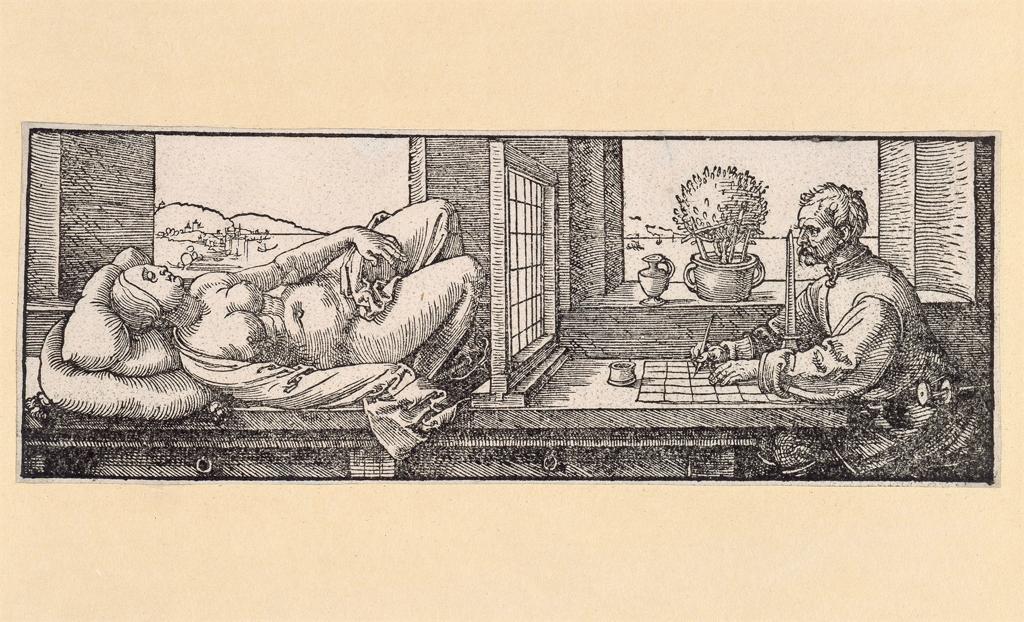

| Andrea Mantegna. (1490). Dead Christ. Tempera on canvas | Albrecht Dürer. (1538). Perspective Drawing. Woodcut |

Renaissance painters enhanced the naturalistic accuracy of their figures through Foreshortening. As we see in the Dürer woodcut, they devised drawing machines with gridlines to precisely capture not just the outline, but also the depth of their subjects, often human models.

Van Eyck: Oil Paint Pioneer

Jan van Eyck was a Flemish master patronized by the emerging wealth of Northwestern Europe. In his Madonna of the Fountain, we see the Renaissance transformation of Byzantine tradition. The figures are standard fare: Madonna, Christ child, adoring angels. But, the figures are located in a specific garden with a contemporary fountain. And the Pathos of mother and child emerge from a moment of active, adoring intimacy.

|

| Virgin of the Fountain (1439). Oil on oak. |

Do you notice that the medium of van Eyk’s Virgin of the Fountain: “oil on panel”? Citations for our images of art generally include this information. Why?

Well, the Medium is always a crucial part of an artistic work. We focus on a painting’s image, but it is composed of materials and technique. And the materials not only constrain the technique, but also form part of our experience. “From the late twelfth to the early sixteenth centuries,” most European painters worked in “egg tempera, in which the pigments of the paint are mixed (or ‘tempered’) with egg yolks.” Tempera provided a “vivid and luminous” effect, but was limited in color options” (Tempera). It also dried fast, restricting brushwork and texture. Jan van Eyck was among those who pioneered a new medium: oil paint.

van Eyck’s Technical Influence

Van Eyck revolutionized [oil painting] technique and brought it to a sudden peak of perfection. He showed the medium’s flexibility, its rich and dense color, its wide range from light to dark, and its ability to achieve both minute detail and subtle blending of tones (Oil Paint Chilvers).

Jan van Eyck’s unprecedented technical mastery of light and space, together with his innovative use of oils, gained him the admiration of painters … and collectors. … Vasari attributed the invention of oil painting to Jan van Eyck; this claim is inaccurate, but it is an extraordinary testimony to Jan van Eyck’s reputation in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe (Eyck, Jan van).

The development of Oil paint by Flemish artists such as Van Eyck vastly increased painters’ capabilities. Oil suspends and fixes color pigments, but dries slowly and permits almost infinite working and reworking by the artist. Oil paint can also be applied in layers, creating textures that painters use with great variety and effectiveness. Impasto, for example, applies paint “in thick solid masses” (Campbell Oil Painting).

van Eyck’s Portrait of a Man with a Red Turban illustrates the subtlety, richness, and vividness that can be achieved in oil. For the full impact of the technique and textures of brushwork, paint, and surface, of course, one must stand before the original painting. But zoom in to gain a much richer experience. In the portrait of Gonella, we see—gasp!—humor. Renaissance art is escaping the Church monopoly with its dour obsession with the death of Christ. Notice, too, the rich, organic modeling and colors made possible with linear perspective and oil paint.

|

|

|

| Portrait of a Man with a Red Turban. (1433). Oil on Oak. | Gonella, Court Dwarf of Dukes of Ferrara. (1433). Oil on oak. | Arnolfini Portrait. (1434). Oil on Panel. |

Now, van Eyck didn’t simply pioneer oil paint. He richly explored the interplay of light and space in our vision. In Van Eyck’s so-called Wedding Portrait[3] of the Arnolfinis, notice the domestic details: the dress of a wealthy merchant and his wife, the furniture, the drapery, the slippers in the corner, the terrier. Notice the linear perspective of the walls and floorboards. And do you see the convex mirror on the back wall? It presents the reverse image of what we see! Renaissance painters loved to play with sight lines and visual effects.

[3] Wedding Portrait: this traditional title, not chosen by van Eyck, is actually misleading. Scholars today are sure this is not a wedding, and the painting is today often entitled Arnolfini Portrait.

Sandro Botticelli: Piety and Myths

Few artists live out the Renaissance tensions between religious and secular commitments more dramatically than does Sandro Botticelli. The Florentine master was patronized by the wealthy and powerful Medici family in Florence, and spent his life in the city. As was the norm, “the bulk of his work was devoted to religious subjects,” However, Botticelli “also painted portraits and allegorical, literary, and mythological themes” (Botticelli, Sandro). Above, we explored Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi last week, noting the fusion of religious subjects with contemporary figures, including Medici patrons. This time, notice the architecture’s linear perspective, contemporary in design but ruined to suggest antiquity.

|

|

|

| The Adoration of the Magi. (1478). Tempera. | Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist. (1468). Tempera and oil on panel. | Portrait of Man Wearing a Medal of Cosimo the Elder. (1474). Tempera. |

At first glance, the Madonna and Child above may seem the same old thing. But notice that this moment of child care is set, not in a timeless heaven, but in a specific moment of time and in a specific place. Byzantine Madonnas frequently added saints out of time, but John the Baptist here is a young lad. When we remember that he was Jesus’ older cousin (Luke 1), the moment becomes a specific memory of shared childhood.

Now consider his facial features. Botticelli remains renowned for his “draftsmanship, … an extraordinary combination of delicacy and flowing vitality” (Botticelli, Sandro). Many of his faces achieve a luminous, idealized quality not necessarily reflective of the Mediterranean features of Florentine citizens. They harken back to Greek ideals of proportion and elegance, as we see in this portrait of a patron wearing a medallion of Botticelli’s Medici masters. We see this idealism most prominently in the mythological paintings that Botticelli painted for the private enjoyment of his patrons. The Medici richly enjoyed humanistic literature and would have been familiar with Ovid and other Classical mythographers. So Botticelli sometimes set aside the task of illustrating Christianity to paint visions of a mythic world.

|

| Botticelli, Sandro. (1478). La Primavera.[4] [The Allegory of Spring]. Tempera on panel |

La Primavera could not have been painted in Europe before the 15th Century. It depicts, not a biblical scene, but a seasonal transformation from Classical myth. This image would never be commissioned for a church. It was patronized by private, Medici wealth and reflected the new dissemination of Greek mythology. From this point on, sophisticated people would have to know Ovid as well as the Bible to understand art. Can you make out any of the figures?

Who is the woman in the center? No, it is not Mary.[5] This is Venus, the Roman name for Aphrodite, Greek goddess of love. Her son, Cupid (Eros) hovers above her while Mercury[6] looks skyward and the Three Graces[7] celebrate new life. To the right, a mythic miracle unfolds before our eyes. The blue figure is Zephyrus. personification of the West Wind. His warming breath transforms Chloris, an incarnation of winter, into Flora, goddess of vegetation.

[4] Primavera is Italian for “First Green,” i.e. spring.

[5] The Virgin was traditionally clothed in virginal blue, honored by the use of ultramarine, the most expensive pigment of the day.

[6] Mercury: Roman name for Hermes, messenger of the gods, always shown with wings.

[7] Three Graces: in Greek mythology, goddesses representing charm, nature, beauty, goodwill, and fertility.

3. Age of Leonardo and Michelangelo

Leonardo—Renaissance Man

Vasari’s 3rd Renaissance stage is centered on the “big three” among revered artists of the age: Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo. Today, the phrase “Renaissance Man” refers to one blessed with many gifts who achieves greatly in a variety of fields. It derives from the fact that wealthy patrons expected an artist in their employ to be ready to paint, sculpt, plan buildings, design costumes for masques, and more. One Renaissance Man reigned supreme: Leonardo da Vinci.

One of the most widely creative people in human history, Leonardo really did everything, much of it in his mind. He was one of the pre-eminent anatomists of his day, dissecting cadavers to enhance the mimetic accuracy of his sculpture and painting. He sent a letter to the Borgias volunteering to invent new war machines, including helicopters and tanks. Throughout his life, Leonardo sought new designs and techniques, not only for art, but for technology:

Leonardo’s Interests

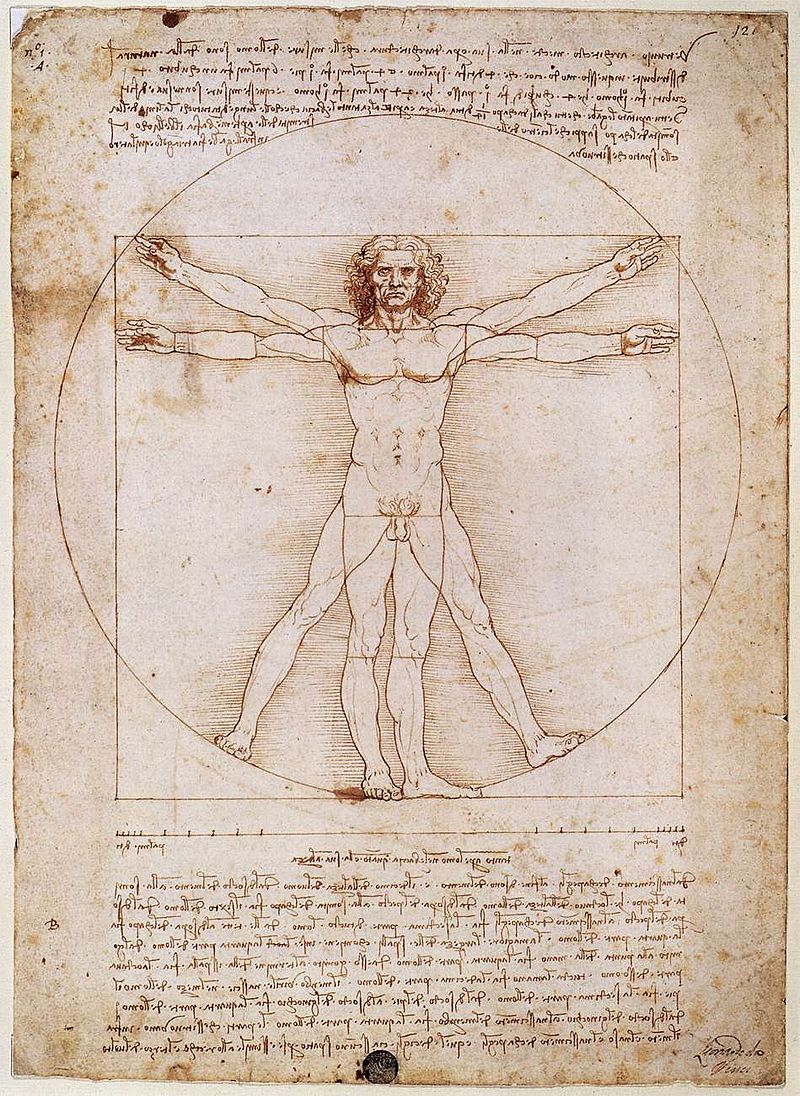

Leonardo’s notebooks remained obscure for centuries, in part because he wrote text backwards, a mirror image. However, his now famous sketch of Vitruvian Man shows a mathematical interest in proportion reminiscent of the Greek Ideal.

|

|

|

| Vitruvian Man (1492). Pen, ink, water color, paper. | Annunciation. (1472). Oil on panel. | Madonna of the Carnation. ( 1478). Oil on canvas. |

Like Fra Angelico’s Annunciation (above), Leonardo’s version depicts the angel informing Mary that she will bear the Christ child. This treatment, however, is one moment of time, not a timeless conflation of many eras. The depth of the painting and the rich naturalism of the landscape gain from masterful Linear Perspective, seen especially in the lines of the building

Like other painters else in his day, Leonardo painted Madonnas enriched by the new interests in naturalism, time and place. His Madonna of the Carnation captures the features of a specific model, dressed in the sumptuous fashions of 16th Century Milan. Foreshortening gives rich contours and textures to the figures, and the Alps rise through the windows of the room. Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks sets new standards for dramatic setting. Behind a family grouping—Mary, an angel, young John the Baptist, and Jesus—looms a forbidding landscape of jagged rock outcroppings. An archway to the left appears to be filled with the teeth of a monster. The background almost overpowers the central grouping of iconic figures. Still, those figures are worthy of notice. They are “composed” (i.e. arranged) in a loose circle defined in part by their eye lines. The figures gaze lovingly at each other, forming an implied ring of intimacy. This effect reveals character (for the Greeks, Ethos) and also operates as a formal design feature, guiding our eyes.

|

|

| Virgin of the Rocks. (1508). Oil on panel (transferred to canvas). | Mona Lisa. (1503-1506). Oil on panel. |

Of course, Leonardo is most famous today for the small portrait—about 30 by 21 inches—that we know as the Mona Lisa, perhaps the most famous painting in the world. But what makes it so special as a painting? Again, it is difficult to get a sense of the painting’s textures and techniques without standing before it. And a good look is hard to achieve. The salon of the Louvre in which the canvas hangs throngs with visitors determined to glimpse the world’s most famous painting.

Everyone speaks of that enigmatic smile and we wonder, as the song goes, what the woman is thinking. We speak of the woman’s enigmatic smile, but notice how the eyes look directly “into the camera,” so to speak. As we just saw, eye lines can open up the inner character and they profoundly affect our own eyes’ processing of the image.

A close look at the Mona Lisa reveals impossibly rich textures, subtle layers of light, shadow, and color. The brushwork is sublime, blending the textures of the woman and of the atmospheric background into a seamless, organic whole without artificially etched contours. Leonardo called his signature style of brushwork Sfumato:

Sfumato

European painters of the next 400 years would strive to “melt” their brushwork into the organic textures of the subject, all but erasing the traces of the medium.

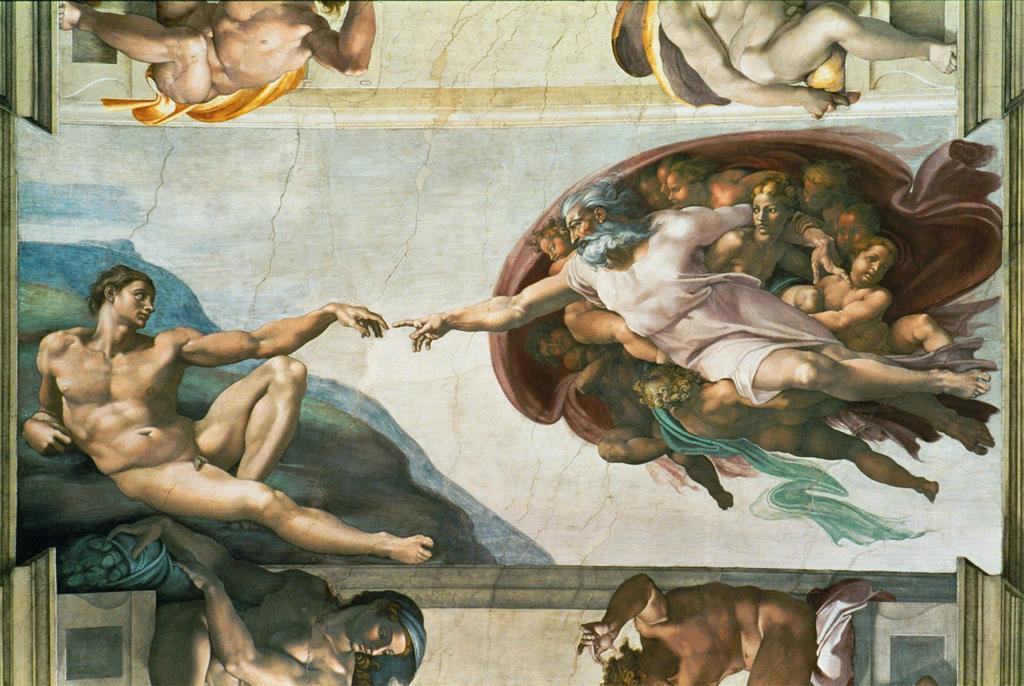

Michelangelo: Christian Humanism

Today, the word Humanism is too often associated exclusively with secularist life philosophies. During the Renaissance, learning later labeled as humanist did influence some skeptics.[8] However, most artists, scholars, philosophers, and churchmen of the day fused classical Greek lore with the faith and ideas of the Latin church.

[8] Skeptics: e.g. Giordano Bruno (1548-1600), a Dominican friar and scholar who theorized about cosmic bodies, advocated pantheism and reincarnation, and was executed by the Inquisition for heresy.

This Christian Humanism finds its pinnacle expression, perhaps, in Michelangelo (see this note). The deeply pious artist focused almost exclusively on Biblical themes. However, his sculpture channeled classical Greek principles. He emulates Classical anatomy and detailed, meticulously Mimetic modeling of the human body. The drapery in his Pieta rivals the naturalism of the finest Greek sculptors. Through Rhythmos and Pathos, this masterpiece inspires faith and empathy with Mary holding the crucified body of her son. Notice how the living woman holds her body’s weight while the limbs of Jesus’ body hang loose and lifeless.

|

|

| Pietà. (1498-1500). Marble. St. Peter’s Basilica | David. (1504). Marble. |

Michelangelo carved his David for the roof of the Duomo (Cathedral) in Florence. But the people of Florence loved it so much that it was placed in the Palazzo Vecchio, the city’s central public square. We find again the principles of Greek sculpture: meticulous anatomy, Rhythmos, Contraposto (uneven distribution of weight on the legs) and ethos (character): the calm, confident gaze of a masterful, born leader.

Of course, this David wears no clothes. Nudes had been unknown in Christianized Europe for nearly 1,000 years. But, embodying the rebirth of Greek classicism, Michelangelo’s predecessor, Donatello, shocked the Renaissance art world when his David wore a floral hat and nothing else. For Michelangelo, the representation of David in the nude was an act of piety. Christian Humanist thought of the day saw human beings as the pinnacle of God’s creation. Michelangelo followed his Greek masters in depicting the male nude as the Greek Ideal of the human form.

|

| Creation of Adam. (1508-1512). Ceiling fresco. Sistine Chapel |

References

Botticelli, S. (1475). The Adoration of the Magi. [Painting]. Florence: Uffizi Gallery. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000464600.

Botticelli, S. (1478) La Primavera. (The Allegory of Spring). [Painting]. Florence, Italy: Uffizi Gallery. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_1031314668.

Botticelli, S. (1468). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist. [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée du Louvre. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/LESSING_ART_10310483097.

Botticelli, S. (1474). Portrait of Man Wearing a Medal of Cosimo the Elder. [Painting]. Florence, Italy: Uffizi Gallery. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_1039778552.

Botticelli, Sandro [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers, (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-489.

Chapman, H. (2001). Raphael. In H. Brigstocke (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001/acref-9780198662037-e-2181.

Chiaroscuro [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-760.

Eyck, J. [Article]. (2003). In G. Campbell (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-1318.

Fra Angelico. (1428). The Annunciation [Painting]. Madrid, Spain: Museo del Prado. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/fra-angelico/annunciation-1432.

Foreshortening [Article]. (2010). In M. Clarke & D. Clarke (Ed.s), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199569922.001.0001/acref-9780199569922-e-742.

Francesca, P. d. (c.1455-60). Flagellation of Christ [Painting]. Urbino, Italy: Palazzo Ducale. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822001048873.

Giotto di Bondini. (ca. 1300.). St. Francis preaching to the birds. Legend of St. Francis [Fresco]. Assisi, Italy: Basilica of St. Francis. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/giotto/st-francis-renounces-all-worldly-goods-1299.

Giotto di Bondini. (ca. 1300.). St. Francis renounces his worldly possessions. Legend of St. Francis [Fresco]. Assisi, Italy: Basilica of St. Francis. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/giotto/st-francis-renounces-all-worldly-goods-1299.

Giotto di Bondini. (ca. 1304). Pieta (Lamentation of Christ’s Crucifixion) [Fresco]. Padua, Italy: Scrovegni Chapel. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31692497.

Holberton, P. (2001). “Sandro Botticelli.” In H. Brigstocke (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001/acref-9780198662037-e-347.

Leonardo da Vinci (circa 1478). Madonna of the Carnation [Painting]. Munich: Alte Pinakothek. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_1039779325.

Leonardo da Vinci. (1472). Annunciation [Painting]. Florence: Uffizi Gallery. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/leonardo-da-vinci/annunciation.

Leonardo Da Vinci. (1492). Vitruvian Man [Illustration]. Venice, Italy: Gallerie dell’Accademia. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vitruvian.jpg.

Leonardo da Vinci. (1503-1506). Mona Lisa [Painting]. Paris: Musee du Louvre. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490423.

Leonardo da Vinci. (about 1508). The Virgin of the Rocks [Painting]. The Louvre, INV 777. https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/virgin-rocks.

Leonardo da Vinci [Article]. (2003). Campbell, G. [Ed.] The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-2159.

Mantegna, A. (circa 1490). Dead Christ [Painting]. Milan, Italy: Pinacoteca di Brera. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490503.

Masaccio. (1427). The Holy Trinity [Fresco]. Florence, Italy: S. Maria Novella. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490520.

Masaccio. (ca. 1427). The Tribute Money [Fresco]. Florence, Italy: Brancacci Chapel. Santa Maria del Carmine. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_870018.

Oil paint [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100247619.

Oil painting [Article]. (2003). Campbell, G. (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-2642.

Michelangelo [Article]. (2003). Campbell, G. (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-2452.

Michelangelo. (1498-1500). Pietà [Statue]. Vatican: St. Peter’s Basilica. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_1039930989.

Michelangelo. (1501-1504). David [Statue]. Florence, Italy: Galleria dell’Accademia. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490336.

Michelangelo. (1508-1512). Creation of Adam [Fresco.] Vatican: Sistine Chapel. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490527.

Sfumato. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-2269.

Still life. (2010). [Article]. In M Clarke & D. Clarke (Ed.s) The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199569922.001.0001/acref-9780199569922-e-1614.

Tempera. (2003). [Article]. In G. Campbell (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-3461.

Van Eyck, J. (1434). Arnolfini Portrait. (Wedding Portrait) [Painting]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/PC_23410_104.

Van Eyck, J. (1433). Gonella, the Court Dwarf of the Dukes of Ferrara [Painting]. Vienna, Austria: Art History Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039902034.

Van Eyck, J. (1433). Portrait of a Man [Painting]. London: National Gallery, NG222. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ANGLIG_10313768464.

Van Eyck, J. (1439). Virgin of the Fountain [Painting]. Belgium: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039902033.

primarily an Italian form, a method of wall painting in which powdered pigments dissolved in water are applied to wet, freshly applied plaster, the color being absorbed into the drying plaster as a binding medium (“Fresco”).

the illusion of depth in a 2 dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which lines angle toward a vanishing point.

a qualification accorded to art which strives to meticulously emulate "the real thing" in nature and reality.

an illusion of depth in a two dimensional image (e.g. a painting) created by contrasting the sizes of objects on the basis of how near or far they are from the eye of the viewer (Foreshortening ).

the Greek term for emotion. In ancient Greek art, the emulation of human emotion and experience within the appearance of human figures.

A term used to describe both the various methods and materials used by artists. For example, painting, drawing, and sculpture are three different media, and bronze and marble are two of the media of sculpture. More spe-cifically, ‘medium’ also refers to the liquid in which pigment is suspended in any kind of painting, for example linseed oil is the most commonly used medium in oil paint (Medium).

a medium for fixing pigment (i.e. a kind of paint) in egg yolks to achieve a vivid and luminous effect. Limited in color options and quick to dry, thus requiring fast painting technique and restricting the painter’s ability to work and rework the medium (Tempera).

a medium (paint) developed during the Renaissance that suspends and fixes color pigments but dries slowly and permits almost infinite working and reworking by the artist. Applicable in layers, creating textures that painters use with great variety and effectiveness (Campbell Oil Painting).

in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity. More generally, an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past.

a pervasively influential era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate images and actions in time and space.

for the classical Greek philosopher Plato, the unchanging and imperceptible Ideas or Forms which all perceptible objects imperfectly copy. In classical Greek art, an attempt to reproduce the best of nature, but also to improve on it, eliminating the inevitable flaws of particular examples through systems of proportions, balance, and expression that bring order, serenity, and completeness (Ideal).

the blending of tones or colors so subtly that they melt into one another without perceptible transitions—in Leonardo's words, “without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke.” Leonardo was a supreme exponent of sfumato, … one of the distinguishing marks of ‘modern’ painting” (Sfumato).

a shift in values and interests among 14th Century European scholars from a narrow, exclusive focus on Christian themes to interest in cultural traditions outside the Christian sphere. Special interest in classical Greek texts and art made possible by the importation into Europe of Arab learning. The conceptual basis for the breakthroughs of Renaissance art. More broadly a philosophy, or political stance which privileges the welfare of humans and assumes that only humans are capable of reason (Humanism).

an orientation of the Christian faith that embraces human cultures and achievements and celebrates human reason as the pinnacle of God’s creation. During the 14th Century, an explosion of interest among the scholars of Europe—almost all of them members of the clergy—in Greek learning that had been lost for a millennium and was once again available through Latin translations of Arab scholarship. The theoretical foundation for the work of Christian artists such as Fra Angelico, Botticelli and Michelangelo.

a conventional theme for paintings and sculptures in the Medieval Catholic Church. A Pieta shows Mary and perhaps other followers grieving over the body of Jesus after his crucifixion.

in classical Greek art, a naturalistic sense of movement that emulates the the patterns of motion and adjustment in the body in the performance of an action (Silberman, Stansbury-O’Donnell, Rhodes).

a representation, usually in sculpture, of a human figure that approximates the appearance and movements of the real human figure, rather than relying upon a series of more abstract conventions (Silberman, Stansbury-O’Donnell, Rhodes). In Classical Greek sculpture, an unequal distribution of weight on a figure’s legs, emulating the way people actually stand.

a philosophical orientation which privileges the welfare of humans and assumes that celebrates the human capacity for reason and cultural achievement