9 Wheat, Pine, and Iron: The Late Nineteenth Century

Massive and fundamental changes characterized the 35 years between the close of the Civil War in 1865 and the dawn of the 20th century. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the nation first focused on how best to bring the defeated southern states back into the Union. During the Reconstruction Period (1865-1877), the states ratified three amendments to the U.S. Constitution that hoped to redefine the relationship between the nation and those it had formerly enslaved. The 13th Amendment ended slavery, the 14th Amendment extended citizenship and the promise of equal rights to those formerly enslaved, and the 15th Amendment purported to protect voting rights for African American men. These amendments, initially undercut by Supreme Court rulings and state and local resistance, served as the basis from which the struggle for racial equality in the nation and in Minnesota developed for the next century and beyond.

West of Minnesota, the struggle between the U.S. government and indigenous nations over land continued. Treaty making went on into the early 1870s before Congress outlawed the process and began legislating for indigenous people (who were, importantly, not yet represented in Congress). As it had in Minnesota, federal Indian policy continued to fail and lead to devastatingly brutal warfare, including, but not limited to: Red Cloud’s War (1866-67), the Red River Wars (1874-75), Battle of Little Bighorn (1876), and the Nez Perce War (1877). This era of organized indigenous resistance to western settlement and the reservation system came to a distressing end with the massacre of Lakota men, women, and children at Wounded Knee Creek in December of 1890.

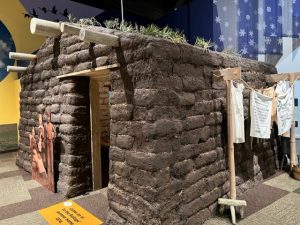

In a misguided effort that had devastating consequences, the U.S. government began allotting indigenous reservations in 1887 by breaking up communally owned land and assigning small plots to individuals. Unallotted lands left over were then sold to white families in the hopes that they would establish farms and provide examples for indigenous people to follow. This policy ended in disaster. Over the next ½ century, poverty increased, and indigenous people lost 60% of their land. Closely related to the allotment policy, the federal government also began to establish Indian boarding schools that took indigenous children from their homes – sometimes through force or coercion – and placed them in residential schools where they were forced to cut their hair, wear Euro-American styled clothes, speak only in English, and provided with a mix of liberal arts education and vocational training. These policies – clearly an attempt to subvert indigenous culture – remained in place well into the 20th century.

By the late 1890s, the western portions of the nation were largely settled by Euro-Americans, and the country had expanded its economic and military presence throughout the Caribbean and well into the Pacific Ocean. In 1867, the United States acquired Alaska from Russia. Three decades later, during the Spanish-American War in 1898, the U.S. acquired Puerto Rico and claimed control of Cuba, while adding possessions throughout the Pacific that stretched to the Philippines. Over the objections of native Hawaiians, the U.S. also annexed their kingdom before the century was out. In just a handful of years, the United States had become an imperial power and a major player on the world stage.

As the American foreign policy matured, people continued to immigrate to the nation in astonishing numbers. Just short of 12 million people arrived between 1870 and 1900. Earlier in this period, people from Ireland and Germany predominated, but by the close of the century, more immigrants arrived from southern and eastern Europe. Chinese immigration into the West Coast resulted in white backlash that led to their exclusion in 1882. African Americans, too, began to leave the rural South for the growing urban centers in the North – a trend that continued and accelerated into the next century. These immigrants and migrants helped build the country’s infrastructure from city streets and sewers to the nation’s canals and transcontinental railroads.

The era was also one of innovation, industrialization, and urbanization. Innovation changed the way people lived and worked. Inventions like the flush toilet, telephone, electricity, light bulb, frozen foods, and steel all emerged during the late 19th century and transformed the country and the state. These inventions led to changes in the way products were developed, both in terms of technology (first steam and later electricity) and in economies of scale. Coupled with mass immigration, the innovations that paved the way for industrialization set the stage for massive growth in the country’s urban areas.

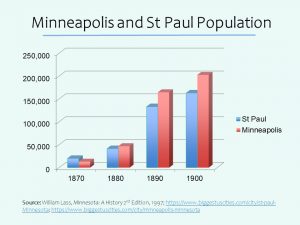

In Minnesota, all of these factors – mass immigration and migration, innovation, industrialization, and urbanization – combined to transform the state. Immigrants and migrants settled the land taken from the Ojibwe and Dakota and established farms. They also worked in logging camps and, a bit later, in iron ore mines. Technological advances in lumber and flour milling allowed Minneapolis to develop into a major metropolitan area and outpace Saint Paul in terms of population and economic might. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Minnesota loggers and saw millers helped build the nation, Minnesota farmers and Minneapolis flour millers helped feed the nation, and Minnesota’s iron ore miners provided raw materials necessary to build the nation’s developing steel infrastructure.

People

Section Highlights

- Minnesota, reflecting the country in general, experienced high levels of immigration during the late 19th century.

- 1/7 of Minnesota was settled by people staking homestead claims.

- Railroad companies received land grants from the government as an incentive to build railways and then sold that land to settlers.

- Saint Paul Archbishop John Ireland worked to settle Irish immigrants in Minnesota.

- James J. Hill’s career intersected many themes that defined the late 19th century, including: railroad construction, immigration, industrialization, agriculture, etc…

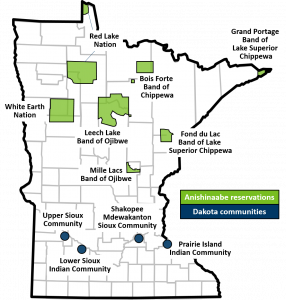

- In 1886, the federal government established four Dakota communities to replace the reservations redacted after the US Dakota War of 1862.

- Ojibwe reservations, except for Red Lake, were subject to allotment under the Dawes (1887) and Nelson (1889) Acts.

- Twenty-one American Indian boarding schools operated in Minnesota in an attempt to assimilate Dakota and Ojibwe children.

The trend of large numbers of immigrants from Europe and migrants from New England and Great Lakes states moving to Minnesota that began during the territorial period accelerated in the aftermath of the Civil War. The 1860 census counted 172,023 people in Minnesota; by 1900, that number had increased to 1,751,394. Many factors brought people to the new state, including: the availability of land and government policies aimed at making land ownership achievable, national immigration and western migration patterns, the extension of railroads into the state, economic opportunities, public and private promoters, and letters from recent arrivals encouraging others to join them in Minnesota.

Coming to Minnesota

Most people came to Minnesota in search of opportunity, and that opportunity was mostly tied to the availability of land. As we have seen, treaties conducted between the 1830s and 1850s had transferred land ownership from the Ojibwe and Dakota to the U.S. Government. The federal government then enacted legislation that aimed to make it easier for settlers to acquire land and establish small farms. By the 1840s, the federal government was selling land to settlers for as low as $1.25 per acre; by the early 1860s, it began giving land away. The 1862 Homestead Act provided 160 acres of public land to any citizen (or someone in the process of becoming a citizen) who had lived on the land for five years, built a house, and paid a small registration fee. By 1880, new arrivals filed 62,000 homestead claims, accounting for 1/7 of Minnesota’s land base.

Railroads also played a notable role in settling the Minnesota frontier. Since the Territorial days, the construction of railroads in the state had been seen as a prerequisite for rapid growth and economic development. The panic of 1857 and then the Civil War delayed rail development in the state until 1867, when Saint Paul was finally connected to Chicago by rail. By 1880, 3,000 miles of track had been laid in Minnesota. Much of this construction was subsidized by federal, state, and local governments through land grants to railroad companies in exchange for building rail. Granted plots of land on either side of the rail, railroad companies sold them at affordable rates to settlers to fund their construction while at the same time creating a market for the transportation it would soon provide. Given that land close to the railroad was more valuable, many new Minnesotans purchased land from railroad companies rather than staking a homestead claim.

It seemed that everyone in Minnesota worked to encourage more people to come. The territorial and state governments established agencies to help encourage immigration, railroad companies hired land agents who coaxed people on the East Coast to choose Minnesota, authors penned books and newspapers editors wrote stories touting the benefits of the state, and new immigrants wrote home to their families and friends encouraging them to follow their lead and immigrate to Minnesota. In one of the most famous examples of private boosterism, John Ireland, the Catholic Bishop in St Paul, worked tirelessly to bring Irish Catholic immigrants from eastern cities – and in some cases Ireland itself – to the Minnesota frontier.

Another Minnesotan, James J. Hill, played a crucial role in the larger story of the late 19th century. Most remembered today for building the Great Northern Railroad that connected Saint Paul to Seattle in 1893, Hill’s life and work connected a number of aspects of the late 19th century that defined the time. An immigrant from Canada, Hill arrived in Saint Paul in 1856 and built his fortune and railroad empire. In doing so, he encouraged others to immigrate and purchase land along his line, utilized innovation and the latest technologies to become a leading industrialist of his time, experimented with the latest agricultural techniques on farms established on his land holdings, and profited from purchasing and selling land on what became Minnesota’s iron range. He also endured difficulties associated with economic downturns, particularly in 1893, that led to labor disputes. He later battled the U.S. government over his massive Northern Securities railroad holding company that federal regulators dismantled after declaring it a monopoly. Today, many of the rail lines laid by Hill’s companies are still in use. His Summit-Avenue mansion, now a historic site administered by the Minnesota Historical Society, serves as a testament to his success, his impact on St Paul and the nation, as well as the excesses of late 19th-century wealth inequalities.

Surviving Rapid Change: Dakota and Ojibwe

In the wake of the U.S. Dakota War of 1862, the U.S. government rescinded Dakota reservation lands and removed most Dakota to reservations west of Minnesota. Just over 300 people who proved they had supported white settlers during the war received special permission to remain in Minnesota. In the subsequent decades, many Dakota people slowly returned to their Minnesota homes and in 1886 the United States government established four communities: the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community, near Prior Lake; the Prairie Island Indian Community, near Welch; the Lower Sioux Indian Community, near Morton; and the Upper Sioux Community, near Granite Falls. These four communities established on land placed in federal trust are much smaller than the original Dakota and Ojibwe reservations, but do include similar federally protected sovereignty status.

In 1887, Ojibwe reservations in northern Minnesota fell victim to general allotment as directed by the Dawes Act. Two years later, the national Congress passed “An Act for the Relief and Civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota.” Known more commonly as the Nelson Act after its sponsor, Minnesota Congressman and soon-to-be Senator Knute Nelson, the act’s official name was misleading. The legislation sought to dismantle most reservations in the state and remove Ojibwe people to allotments on the White Earth Reservation. The act was amended at the last minute in the House of Representatives to allow people to take allotments on their home reservations, so the attempted mass removal ultimately failed. Regardless, allotment’s impact on Ojibwe land ownership was devastating as the government opened all unallotted land to lumber companies and white settlers. By the 1930s less than 1/10th of the White Earth Reservation was still in Ojibwe hands; at Mille Lacs, it was 7%; on the Leech Lake Reservation, it was reduced to 4%. Today, the legacy of allotment is easily seen in reservation maps that resemble a checkerboard of white-owned and Ojibwe-owned plots.

Of all the Minnesota Ojibwe reservations, only the Red Lake Nation escaped the ramifications of allotment. The Red Lake Ojibwe agreed to cede nearly 3,000 acres of their reservation rather than having allotment forced upon them. Today, Red Lake is the only Ojibwe Reservation in Minnesota where land is still held collectively by the Ojibwe, was never subject to allotment, or open to purchase by non-indigenous people.

As the federal government pursued assimilation through allotment of indigenous lands, it also embraced a policy of sending indigenous children to religious or government-run boarding schools. The schools were designed to prepare boys for manual labor and girls for domestic work, all while working to undermine students’ connections to their cultures. The schools forced students to dress in Euro-American clothes, cut their hair, and speak only English. By 1891, the Federal government began requiring that American Indian children be sent to boarding schools and often threatened to withhold annuity payments to encourage parents’ compliance. In many cases, students were enrolled in boarding schools by coercion or outright force. Starting with the establishment of a school on the White Earth Reservation in 1871, Minnesota came to house 21 boarding schools – some connected to Ojibwe reservations and Dakota communities, others not. In just one example, in 1887, the Catholic Sisters of Mercy acquired a federal contract to open a boarding school at Morris. Ten years later, the federal government took over its operation before closing it in 1909. Today, the last remaining building of the school serves as the Multi-Ethnic Resource Center on the campus of the University of Minnesota-Morris. In a softening of the policy in the late 1920s, boarding schools began to be replaced by reservation day schools. Both allotment and the accompanying boarding school era were, in the words of historian Denise Lajimodiere, “a dark chapter in U.S. history.”[1]

Hidden History: Federal investigation generates new interest in MN American Indian boarding schools

ABC Eyewitness News, Channel 5 Minneapolis. September 21, 2021.

Economic Frontiers

Section Highlights

- Late 19th-century economic activities in Minnesota centered on farming, logging, and mining.

- Farming on the Minnesota prairie was difficult. most farmers eventually began growing wheat.

- Bonanza farms were established in the Red River Valley.

- The lumber industry depleted Minnesota’s pine stands by the early decades of the 20th century.

- Minneapolis developed into a major urban area largely due to waterpower at Saint Anthony Falls and the lumber and flour mills that were established there.

- Iron ore from the Vermillion, Mesabi, and Cuyuna ranges supplied the nation with much-needed iron ore to produce steel.

- Iron Range towns attracted large numbers of immigrants from 43 different nations.

Of the reasons that drew people to Minnesota, opportunities to earn a living and make a better life for themselves and their families topped the list. Minnesota’s late 19th-century economy was dominated by what historian William Lass called the three frontiers: farming, logging, and mining.

Farming on the Minnesota Prairie

While some made a living working in lumber camps, or the iron ore mines, or in the growing cities like Minneapolis and St. Paul, most newly arriving Minnesotans came to farm. While farmers experimented with a variety of crops as they initially worked just to feed their families, wheat soon became the crop of choice for commercial production. By the late 1850s, Minnesota farmers were exporting small quantities, which expanded markedly during the Civil War. By 1878, 70% of Minnesota’s farmland was growing wheat, and by 1890, the state had become the nation’s largest producer.

While federal policies provided low-cost access to land, farmers on the Minnesota prairie faced immense challenges. The financial difficulty associated with acquiring the most recent mechanized farming equipment, the unpredictability of Minnesota weather, unprecedented plagues of locusts that devastated crops and most everything else during the 1870s, and unregulated railroad freight rates and grain grading all made making a comfortable living farming the Minnesota frontier elusive. In 1887, Mary Carpenter, who had been struggling with her husband to farm in southwestern Minnesota for over a decade, lamented that these challenges made “life seem long sometimes.”[2]

In an attempt to address some of the difficulties faced by farmers, a New England-born farmer near Elk River, Oliver H. Kelly, worked to establish the Grange – an organization that hoped to “educate farmers and their families, enrich their social lives, and share information on the growing of crops.”[3] In 1867, Kelly played the leading role in establishing the National Grange of the Patrons of Husbandry in Washington, D.C. Two years later, he successfully established the Minnesota State Grange – the first in the nation. Local granges provided social activities for their members, assisted them in selling crops and livestock, and advocated for the creation of cooperatives to level up purchasing power. While not a political party in itself, the Grange helped farmers organize into a political force by the end of the century.

Although most of the land in Minnesota was farmed by small family farms, during the 1870s a unique set of circumstances led to the development of huge commercial farms in the Red River Valley in northwestern Minnesota and the eastern sections of the Dakotas. These bonanza farms typically ranged from 4,000 to 10,000 acres (although the largest exceeded 25,000 acres), utilized cutting-edge horse-drawn mechanization, and flourished throughout the valley well into the 20th century. Availability of large tracks of land from railroad grants, available technology that allowed for mechanization, and a seemingly insurmountable demand of the Minneapolis flour mills worked together to create the environment in which this commercial farming flourished.

Logging the Minnesota Pine Stands

Even before farming drew settlers to Minnesota, abundant white pine stands interspersed throughout the northern mixed forests drew the attention of lumbermen. Loggers prized white pine above all other species because it grew tall and straight, was light enough to float while sturdy enough to build with, sawed easily, and nailed without splitting. In 1839, the first sawmill in what would become Minnesota was established at Marine on St. Croix. By the first decade of the 20th century, 20,000 Minnesota lumberjacks and an additional 20,000 saw millers were producing 2.3 billion board feet of pine lumber per year – enough to build 600,000 two-story homes or to build a nine-foot-wide boardwalk around the globe at its equator.

During the 1840s, logging operations were small affairs, but emerging technology and a seemingly limitless demand transformed the industry by the end of the century. Initially, small crews of lumberjacks felled trees during the winter, stripped them of branches, and cut them to length before using oxen to move the logs to the river shore. Spring thaws brought higher water and allowed river rats to guide logs down the rivers to milling sites where they were sawed into boards suitable for construction. By the 1870s, crews were growing in number and size and were feeding over 200 sawmills throughout the state, including nine in Stillwater and 15 in Minneapolis. Horses pulling large sleds of logs along iced roads were replaced the oxen as steam power allowed sawmill locations to move beyond the natural waterpower required for their predecessors. Steam-powered circular saws and then band saws also increased the efficiency of the mills, now able to operate through the winter due to steam-heated mill ponds.

Prior to the 1890s, logging operations were limited to stands near enough to rivers to ease the effort and expense of transporting the logs to mills. During the last decade of the nineteenth century, however, companies began using narrow-gauge railroads to reach into the untapped pine forests located beyond the natural reach of the rivers. This adaptation, along with other steam-powered technological innovations, ushered in Minnesota’s golden age of logging from 1890 to 1910. Not only did the industry supply the Midwest with needed lumber, it left a legacy of lumberjack lore, including but not limited to the Paul Bunyan stories that are still retold today. While Stillwater, Minneapolis, and Winona are well remembered as early mill towns, Brainerd, Little Falls, Crookston, Cloquet, Duluth, International Falls, and many other cities connect their earliest years closely to their sawmills.

By 1910, the lumber industry in Minnesota was rapidly declining because loggers had depleted what once seemed to be an inexhaustible supply of white pine. Sawmills closed, and lumber barons moved their operations to the Pacific Northwest. Minnesota’s pineries were clear-cut and littered with rotting stumps, discarded branches, and dried treetops known as slash. This discarded landscape was susceptible to forest fires, which were often started by sparks emitted by trains. While the devastated Hinckley fire of 1894 is most often remembered, Chisholm burned in 1908, as did Baudette in 1910, and Cloquet-Moose Lake in 1918.

The lumber industry provided a necessary product for a growing country. In doing so, it employed tens of thousands of men and provided the industrial origin of many of the state’s towns and cities. In Minneapolis specifically, a significant amount of capital made in the lumber industry was reinvested into the city’s growing flour milling infrastructure. Industrialized logging also had a downside, however. By treating the pine forests as a commodity, we allowed a largely unregulated industry to clear-cut the forests, which devastated the landscape and left some Minnesotans dangerously vulnerable to forest fires.

Minnesota: A History of the Land “When White Pine Was King”

View the last part of the first episode of Minnesota: A History of the Land. The clip, which is about 20 minutes long, provides a nice overview of the early lumber industry in Minnesota. The video player will begin at the section I want you to view.

Sawdust Towns Grow into a Mill City

In the decades following the Civil War, Minneapolis emerged as the undisputed urban and industrial center of Minnesota and the upper Midwest. Waterpower available at Saint Anthony Falls, proximity to the region’s major river systems, pine stands, and farmable prairies, a seemingly insatiable demand for lumber and flour, a massive workforce, and an energetic class of entrepreneurs all contributed to Minneapolis’s rise. This combination of natural advantages and focused human enterprise resulted in phenomenal population growth and rapid economic development. From 1870 to 1900, the city’s population grew from 13,066 to 202,738, surpassing Saint Paul, which was itself experiencing a population boom. Harnessing the power of the falls, the city became the nation’s largest saw milling center by the end of the century and the world’s largest flour producer – a title it held from 1880 to 1930.

Foremost among Minneapolis’s natural advantages were the processing power and location of St Anthony Falls. The falls lie near the meeting points of the area’s major river systems and within the ecological seam separating the mixed pine stands of the north and the vast prairies of the west. Geographer David Lanagren suggested that this arrangement was a near “perfect landscape,” in which pine logs from the north and wheat from the west were easily transported to Minneapolis, where innovation harnessed the power of Saint Anthony’s moving water to mill logs into boards and grind wheat into flour. Without question, the Falls of Saint Anthony served as an important foundation on which Minnesotans built the city of Minneapolis.

Early on, Minnesotans understood the economic potential of the Falls of St Anthony. In 1838, shortly after the U.S. Government acquired title to the land from the Dakota, Franklin Steele, a civilian storekeeper at Fort Snelling, staked a claim on the east side of the falls. By the end of the 1840s, Steele had harnessed the waterpower at the falls and platted the city of Saint Anthony. After the 1851 treaties opened the west side of the falls to settlement, the city of Minneapolis emerged and was incorporated in 1867. By the time Minneapolis enveloped Saint Anthony in 1872, its population was rapidly expanding, it had replaced Stillwater as the sawmilling center of the region, and its flour milling capacity was growing exponentially.

Beginning with Franklin Steele’s mill that opened in 1848, sawmilling quickly became the first large-scale industrial activity at the falls. By 1869, sixteen sawmills lined both sides of the falls and sawed nearly 91 million board feet of lumber annually. By the time Minneapolis became the nation’s leading sawmilling center in 1899, capable of milling 960 million board feet a year, steam power had allowed the mills to move away from the falls and into north Minneapolis. The reign as the leading “sawdust city” was destined to be short-lived, however. Northern pine stands that early observers thought were inexhaustible were depleted in the early 20th century. By 1906, Minneapolis had lost its title as the leading lumber producer, and by 1910, nearly all the sawmills had closed as the industry moved on to the Pacific Northwest. The fifty years lumbermen sawed logs into boards in Minneapolis played a critical role in the city’s development – providing employment, spurring related industries, and accumulating capital that in some critical cases was reinvested into other industrial pursuits, chief among them, flour milling.

Flour milling developed along with Minneapolis’s sawmills and proved a bit more enduring. In addition to the waterpower available at the falls, several other factors allowed Minneapolis to rise above all others and by 1880 become the flour milling capital of the world. First, railroads connected the city to the nearby and expanding wheat-growing region that spanned from Minnesota’s Red River Valley, through North Dakota and South Dakota, and into Montana. Second, industrial innovation allowed millers to not only increase milling capacities but also solve challenges associated with processing the type of wheat able to reliably grow in the region. Third, millers worked together to develop ship and rail transportation options that bypassed Chicago and allowed for the export of flour to the East Coast and beyond.

Water-powered commercial flour milling began at the falls in the 1850s. During the following decade, milling capacity increased, and by 1871, 13 flour mills operated at the falls. Regardless of this growth, Minneapolis-milled flour had earned a dismal reputation. In short, the type of wheat grown in the northern regions of the country was more difficult to process into desirable flour. Spring wheat (planted in the early spring and harvested in the late summer) had a hard and brittle husk that required milling at higher speeds, which caused the flour to burn and darken, while shattered husks further speckled the flour. To make matters more difficult, the gluten and starch in the grain were not easily mixed enough to prevent the flour from quickly turning rancid. To address these challenges, Minnesota millers moved away from the traditional stone grinding wheels and applied the latest technological innovations – in some cases swiped from Europe – to develop “New Process” flour. The process removed cracked husks with jets of air early in the process and used a series of porcelain, iron, or steel rollers to gradually reduce the flour and more completely mix the starch and gluten. The results produced a white flour with more nutrient value and baking yields than flour made from winter wheat grown and milled in other sections of the country.

Just as innovation was allowing Minneapolis to emerge as a flour-milling behemoth, tragedy struck. On the evening of May 2, 1878, the Washburn A Mill, then the largest in the world, exploded, killing 18 workers, destroying adjacent mills and buildings, and rattling the windows of homes in Saint Paul, ten miles away. The explosion, caused by ignited flour dust, shocked the city and destroyed 1/3 of its milling capacity in an instant. The Minneapolis Tribune called the disaster a “calamity, the suddenness and horror of which it is difficult for the mind to comprehend.”[4] Mill owner Cadwallader Washburn rushed from his home in La Crosse, Wisconsin, to pledge that he intended to rebuild the mill and did so with the latest New Process technology coupled with dust collectors to reduce the likelihood of another catastrophe. By the time Washburn made good on his promise and the second Washburn A Mill opened in 1880, it was one of 22 mills on the west side of the river alone. That same year, Minneapolis overtook Budapest, Turkey as the largest flour producer in the world – a title it held for ½ a century.

This massive expansion and industrial development, however, came at a hefty price. While saw and flour mills eventually moved away from waterpower to steam and then electricity, millers manipulated the falls in the early years of development to increase access to moving water. Nearly three miles of canals, headraces, tailraces, and tunnels undermined the fragile integrity and natural beauty of the falls. In 1869, an attempt to tunnel under the river to divert more water to prospective mills collapsed and nearly destroyed the falls altogether. While the Army Corps of Engineers later engineered a solution and installed first a timber and later a concrete apron protecting the falls, urbanization, industrialization, and capitalism had fundamentally transformed the falls from a stunning, natural phenomenon to something unrecognizable. The city that had grown up surrounding the falls was also heading toward a public health crisis resulting from its unprecedented growth and lack of public utility infrastructure. It was a crisis in the making that Minnesotans would confront in the coming century.

Mill City Museum

Mining the Minnesota Ranges

If Minnesota’s economic development was a three-legged stool with pine and wheat representing two legs, the third leg was made of iron. The sense that the land west of Lake Superior in northeastern Minnesota held valuable mineral wealth had existed since European traders first visited the region. After a fruitless quest for gold around Lake Vermillion in the 1860s, the region’s iron ore deposits began to attract attention. By the early 20th century, Minnesotans had discovered and began mining three iron ranges: the Vermillion, which began producing ore in 1884; the Mesabi, which began producing ore in 1892; and the Cuyuna, which began producing ore in 1911. By the early 20th century, the region’s iron ore had attracted tens of thousands of mostly immigrant miners, the investment of the country’s most powerful industrialists (including John D Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Henry Oliver, and James J Hill), and had emerged as the nation’s leading iron ore producer.

In the early 1880s, Duluth businessmen and promoter George Stone partnered with Charlemagne Tower and other capitalists from the East Coast to create the Minnesota Iron Company. The company quickly opened the Soudan Mine, the state’s first, near the western edge of the Vermillion Range. As the company founded the settlements of Tower and Soudan to house its miners, it constructed the Duluth and Iron Range Railway that connected the mine to Two Harbors on the western shore of Lake Superior. In the fall of 1884, the first train cars filled with iron ore arrived at Two Harbors to be shipped across Lake Superior to Cleveland’s blast furnaces. Initially mined in open pits, the vertical veins of ore descending deep into the ground required miners to build underground mines at Soudan and other mining locations on the Vermillion. Between the 1880s and the 1960s, eleven different mines operated along the Vermillion Range, which spanned north and east from Tower to Ely. The Soudan Mine was the largest of all the Vermillion mines and reached its peak production in 1892 when it produced over 586,000 tons of ore. The mine eventually descended some 2,500 feet below the surface and operated until 1962, when technological advances allowed lower-grade ore, more easily mined at other locations, to be efficiently refined into steel. Two years later, in 1964, the last mine on the Elly side of the Vermillion shut down.

Even before the Vermillion Range successes drew more attention to the Mesabi Range, a Duluth-based timber cruiser, Lewis Merritt, had convinced himself the area held ore. While Merritt was not able to make his long-sought-after discovery during his lifetime, shortly after his death, his sons did. In 1890, the Merritt sons finally discovered what their father was unable to find – marketable ore on the Mesabi at a place they named Mountain Iron. It had been difficult to find because it was different than the Vermillion ore veins. Rather than hard veins of ore embedded in granite, the ore on the Mesabi was soft and lay just feet under the topsoil. While it took a bit more effort to process into steel, it was easily extracted with steam shovels. The Merritts moved quickly to lease land and went about building a railroad to transport their ore to Lake Superior. By 1892, they began shipping ore from the Mountain Iron Mine and several additional mines near Biwabik. Today, Lewis Merritt’s sons are remembered as Minnesota’s “Seven Iron Men” for the role they played in opening the Mesabi to mining.

Regardless of the important role the Merritt family played in opening the Mesabi, their success proved short-lived. To finance the construction of their railroad and ore docks in Duluth, they borrowed money from John D. Rockefeller in 1892. The following year, the country plunged into an economic depression, and the Merritts at first borrowed more money from Rockefeller before defaulting on their loans. The Seven Iron Men were forced to sell out completely to Rockefeller and were left with nothing. The Merritt family’s accusations of fraud resulted in an out-of-court settlement in which they received a one-time payment of just $525,000. Moving on and making millions, by 1901, Rockefeller reached an agreement with Henry Oliver, Andrew Carnegie, and others to form U.S. Steel. The US Steel subsidiary, Oliver Iron Mining Company, extracted ore from the Mesabi. Historian Alex Tieberg, explained:

the three men reached a compromise in 1896: Oliver would mine the ore, Rockefeller’s railroad system would transport the product, and Carnegie would transform it into steel. This agreement was finalized in 1901, and United States Steel (USS) was incorporated as the largest corporation in the world.[5]

Mining operations on the Mesabi, the Vermillion, and the Cuyuna drew massive numbers of immigrants to the Iron Range. In 1885, the region’s population hovered around 5,000 people. By 1920, well over 100,000 people lived on the range and worked in the mines. Approximately ½ of the population was foreign-born born and nearly 85% of the miners were immigrants. To accommodate the workforce and associated population, mining “locations” (temporary housing settlements) popped up and moved around with the mines. Some estimate as many as 200 locations existed between 1890 and the 1920s – 175 on the Mesabi alone. These locations sometimes developed into range towns, but more often disappeared when the miners moved on. Towards the end of the immigration boom, southern and eastern Europeans predominated, but 43 different nationalities were represented on the range. Life was difficult, and the work was dangerous, as hundreds of men were killed in the mines. Miners faced unfair treatment and job discrimination, and families often lived in near-devastating poverty. In a disaster that highlighted the dangers of the work, 41 miners were drowned on the Cuyuna Range when the Milford Mine breached Foley Lake and flooded in minutes in 1924.

During the last decades of the 19th century, entrepreneurial vision, industrialization, and a massive workforce began harvesting northern Minnesota’s mineral wealth. The range provided a hungry nation with iron from which it smelted steel and built the country’s infrastructure. Historian Alex Tieberg’s recollections of the Mesabi’s significance can easily be extended to the entire region when he stated the Range “produced iron ore that boosted the national economy, contributed to the Allied victory in World War II, and cultivated a multiethnic regional culture in northeast Minnesota.”[6] Today, six mining companies continue to mine taconite on the Mesabi Range. The taconite pellets are loaded into iron ore ships and shipped across Lake Superior to blast furnaces in places like Cleveland and Pittsburgh – in a process similar to the one developed in the 1880s.

Conclusion

During the second half of the 19th century, Minnesota reflected the rapid changes transforming the nation. Many of the millions of immigrants flocking into the country found their way to Minnesota to farm, fell trees, saw boards, make flour, or mine iron. Others lived their lives in small communities on the prairie or on the range and worked in supporting businesses and raised families. Still others made their lives in larger cities like Minneapolis, which grew into the dominant urban and industrial center of the upper Midwest on the back of lumber and flour. In the face of this rapid change, Dakota and Ojibwe people in Minnesota faced increasing calls to assimilate and worked hard to hold on to their land and culture in the face of enormous pressure.

During this period, Minnesota harvested the state’s abundant resources and came to lead the nation in producing lumber and iron. For 50 years, Minnesota was the world’s largest flour producer. The harvesting of resources – some renewable, some not – had a significant environmental impact. By the end of this period, Minnesotans began to see that the resources they once thought were limitless were indeed limited.

Environmental Impact

The second episode of Minnesota: A History of the Land, typically assigned with this section of the course, investigates the environmental impact of this period.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Anfinson, John O. “St. Anthony Falls: Timber, Flour and Electricity.” In River of History: A Historic Resources Study of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, 117-137. Saint Paul: National Parks Service, 2019.

Danbom, David B. “Flour Power: The Significance of Flour Milling at the Falls,” Minnesota History. Spring/Summer 2003, 271-285.

Lajimodiere, Dr. Denise K. “Native American Boarding Schools.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/native-american-boarding-schools (accessed March 5, 2022).

“Logging Industry,” Forest History Center, Minnesota Historical Society https://www.mnhs.org/foresthistory/learn/logging (accessed February 19, 2022).

Pennefeather, Sharron M. (ed.) Mill City: A Visual History of the Minneapolis Mill District. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2003.

Sundberg, Sara Brooks. “The Letters of Mary E. Carpenter: A Farm Woman on the Minnesota Prairie,” Minnesota History. Spring 1989, 186-193.

Watts, Alison. “The Technology That Launched a City: Scientific and Technological Innovations in Flour Milling During the 1870s in Minneapolis,” Minnesota History. Summer 2000, 86-97.

- Denise K. Lajimodiere, "Native American Boarding Schools." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/native-american-boarding-schools (accessed March 5, 2022). ↵

- Sara Brooks Sundberg, “The Letters of Mary E. Carpenter: A Farm Woman on the Minnesota Prairie,” Minnesota History (Spring 1989), 192. ↵

- Members of the Sunbeam Grange #2. "State Grange of Minnesota." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/state-grange-minnesota (accessed February 16, 2022). ↵

- Nathanson, Iric. "Washburn A Mill Explosion, 1878." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/event/washburn-mill-explosion-1878 (accessed March 2, 2022). ↵

- Alex Tieberg. "Oliver Iron Mining Company." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/oliver-iron-mining-company (accessed March 7, 2022). ↵

- Alex Tieberg, "Mesabi Iron Range." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/place/mesabi-iron-range (accessed March 7, 2022). ↵

Born in County Kilkenny, Ireland, in 1838, John Ireland came to St. Paul with his parents in 1852. He was ordained a Catholic priest in 1861, served briefly as chaplain for the Fifth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment in the Civil War, and was appointed bishop in 1875. By the time he was appointed archbishop of St. Paul in 1888, he was one of the city's most prominent citizens, and he was responsible for recruiting Irish immigrants to settle in communities throughout Minnesota, including Clontarf, Adrian, Graceville, and Ghent.

Kate Roberts, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/ireland-john-1838-1918

James J. Hill fit the nickname “empire builder.” He assembled a rail network—the Great Northern (1878), the Northern Pacific (1896), and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy (1901)—that stretched from Duluth to Seattle across the north, and from Chicago south to St. Louis and then west to Denver. He was one of the most successful railroad magnates of his time.

Paul Nelson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/hill-james-j-1838-1916

The Great Northern Railway was a transcontinental railroad system that extended from St. Paul to Seattle. Among the transcontinental railroads, it was the only one that used no public funding and only a few land grants. As the northernmost of these lines, the railroad spurred immigration and the development of lands along the route, especially in Minnesota.

Aaron Hanson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/great-northern-railway

Sitting on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River and the city of St. Paul, the 36,500-square-foot, forty-two-room James J. Hill House stands as a monument to the man who built the Great Northern Railway. It remains one of the best examples of Richardsonian Romanesque mansions in the country.

Eric Colleary, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/structure/james-j-hill-house

Norwegian immigrant Knute Nelson served state and country throughout his life, first as a soldier and a lawyer, then as a legislator and the twelfth governor of Minnesota. He was the state's first foreign-born governor.

MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/nelson-knute-1843-1923

Native American boarding schools, which operated in Minnesota and across the United States beginning in the late nineteenth century, represent a dark chapter in U.S. history. Also called industrial schools, these institutions prepared boys for manual labor and farming and girls for domestic work. The boarding school, whether on or off a reservation, carried out the government's mission to restructure Native people's minds and personalities by severing children’s physical, cultural, and spiritual connections to their tribes.

Dr. Denise K Lajimodiere, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/native-american-boarding-schools

On June 12, 1873, farmers in southwestern Minnesota saw what looked like a snowstorm coming towards their fields from the west. Then they heard a roar of beating wings and saw that what seemed to be snowflakes were in fact grasshoppers. In a matter of hours, knee-high fields of grass and wheat were eaten to the ground by hungry hoppers.

R.L. Cartwright, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/grasshopper-plagues-1873-1877

For almost 150 years, the State Grange of Minnesota as an organization has thrived, faded, and regrouped in its efforts to provide farmers and their families with a unified voice. As the number of people directly engaged in farming has declined, the State Grange has shifted its focus toward recruiting a new type of member—often younger—interested in safe, healthy, and sustainable food sources.

Members of the Sunbeam Grange #2, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/state-grange-minnesota

The giant lumberjack Paul Bunyan—bearded, ax in hand, clad in red flannel and work boots—has come to represent Minnesota’s Northwoods. Folklore credits him and his sidekick, Babe the Blue Ox, with creating the Mississippi River and the Grand Canyon. But his legacy is complicated. While Paul Bunyan myths celebrate Minnesota, they also leave out the facts of the state’s logging history, which led to deforestation and the displacement of Native American histories, places, and people.

-Kasey Keeler, MNOpedia https://www.mnopedia.org/person/paul-bunyan

On September 3, 1894, a headline of the Minneapolis Tribune screamed, “A Cyclone of Wind and Fire: Northern Minnesota and Wisconsin Bathed in a Sea of Flame and Hundreds of Human Lives are Sacrificed to the Insatiable Greed of the Red Demon as He Stalks through the Pine Forest on His Mission of Death.” In just four hours on September 1, the red demon destroyed an estimated 480 square miles, resulting in massive destruction and over 418 deaths. The fire zone lay within Pine County, which was named for its majestic white pine forests.

Mary Laine, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/great-hinckley-fire-1894

The worst natural disaster in Minnesota history—over 450 dead, fifteen hundred square miles consumed, towns and villages burned flat—unfolded at a frightening pace, lasting less than fifteen hours from beginning to end. The fire began around midday on Saturday, October 12, 1918. By 3:00 a.m. on Sunday, all was over but the smoldering, the suffering, and the recovery.

-Paul Nelson, MNOpedia, https://www.mnopedia.org/event/cloquet-duluth-and-moose-lake-fires-1918

On the evening of May 2, 1878, the Washburn A Mill exploded in a fireball, hurling debris hundreds of feet into the air. In a matter of seconds, a series of thunderous explosions—heard ten miles away in St. Paul—destroyed what had been Minneapolis' largest industrial building, and the largest mill in the world, along with several adjacent flour mills. It was the worst disaster of its type in the city's history, prompting major safety upgrades in future mill developments.

Iric Nathanson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/washburn-mill-explosion-1878

On October 5, 1869, water seeped and then gushed into a tunnel underneath St. Anthony Falls creating an enormous whirlpool. The falls were nearly destroyed. It was years before the area was fully stabilized and the falls were again safe from collapse.

Molly Huber, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/st-anthony-falls-tunnel-collapse-october-5-1869

The Mesabi Iron Range wasn’t the first iron range to be mined in Minnesota, but it has arguably been the most prolific. Since the 1890s, the Mesabi has produced iron ore that boosted the national economy, contributed to the Allied victory in World War II, and cultivated a multiethnic regional culture in northeast Minnesota.

Alex Tieberg, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/mesabi-iron-range

The Cuyuna Iron Range is a former North American iron-mining district about ninety miles west of Duluth in central Minnesota. Iron mining in the district, the furthest south and west of Minnesota’s iron ranges, began in 1907. During World War I and World War II, the district mined manganese-rich iron ores to harden the steel used in wartime production. After mining peaked in 1953, the district began to focus on non-iron-mining activities in order to remain economically viable.

Fred Sutherland, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/cuyuna-iron-range

The discovery of iron ore on the Mesabi Range can hardly be credited to one person. In 1890, however, it was the family of Lewis Merritt that found merchantable ore and opened the Mesabi to industry. Within three years, they owned several mines and had built a railroad leading to immense ore docks in Duluth. On the cusp of controlling a mining empire in northern Minnesota, they lost everything to business titan John D. Rockefeller.

Peter DeCarlo, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/merritt-family-and-mesabi-iron-range

The Oliver Iron Mining Company was one of the most prominent mining companies in the early decades of the Mesabi Iron Range. As a division of United States Steel, Oliver dwarfed its competitors—in 1920, it operated 128 mines across the region, while its largest competitor operated only sixty-five.

Alex Tieberg, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/oliver-iron-mining-company

On February 5, 1924, water from Foley Lake flooded the Milford Mine, killing forty-one miners in Minnesota's worst mining disaster. Only seven miners climbed to safety.

John Fitzgerald, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/milford-mine-disaster-1924