12 Minnesota’s Greatest Generation During the Great Depression, 1929-1941

The Great Depression, World War II, and the economic boom of the late 1940s and 1950 were the defining events of the 20th century. These events transformed our world, nation, and state. In a 1998 book titled The Greatest Generation, Tom Brokaw honored the Americans who endured the Great Depression as teenagers, fought World War II as young adults, and, in mid-life, built the economic foundations for the nation we have today. Of this transformative group of Americans, he wrote:

They came of age during the Great Depression and the Second World War and went on to build modern America – men and women whose everyday lives of duty, honor, achievement, and courage gave us the world we have today.

At a time in their lives when their days and nights should have been filled with innocent adventure, love, and the lessons of the workaday world, they were fighting in the most primitive conditions possible across the bloodied landscape of France, Belgium, Italy, Austria, and the coral islands of the Pacific. They answered the call to save the world from the two most powerful and ruthless military machines ever assembled, instruments of conquest in the hands of fascist maniacs. They faced great odds and a late start, but they did not protest. They succeeded on every front. They won the war; they saved the world. They came home to joyous and short-lived celebrations and immediately began the task of rebuilding their lives and the world they wanted. They married in record numbers and gave birth to another distinctive generation, the Baby Boomers. A grateful nation made it possible for more of them to attend college than any society had ever educated, anywhere. They gave the world new science, literature, art, industry, and economic strength unparalleled in the long curve of history. As they now reach the twilight of their adventurous and productive lives, they remain, for the most part, exceptionally modest. They have so many stories to tell, stories that in many cases they have never told before, because in a deep sense they didn’t think that what they were doing was that special, because everyone else was doing it too.[1]

Members of America’s Greatest Generation were born during the first quarter of the twentieth century (1900-1925). The oldest of them were young adults when the Great Depression began in the fall of 1929, but most of them were children. As a result, economic devastation and uncertainty dominated their formative years.

The Great Depression

Section Highlights

- The October 1929 stock market crashed coincided with the beginning of the Great Depression.

- Initially, the Hoover Administration did little to address the economic devastation.

- In 1932 Franklin Roosevelt was elected President and ushered in the New Deal.

- Roosevelt’s attempts at addressing the Great Depression fundamentally expanded the scope and size of the federal government – and what Americans expected from it.

Ill-advised government policies, unchecked stock-market speculation, a growing gap between the rich and the poor, and over production coupled with under consumption, all set the stage for an abrupt end to the general prosperity enjoyed by much of the nation during the 1920s. The stock market had reached its all-time high in September of 1929, but began to slip the following month before crashing on “Black Tuesday,” October 29 when it plummeted $14 billion. By the end of 1929, the market was worth ½ of what it had been worth just three months earlier – by 1932 it had lost $74 billion. The crash began a ripple effect that impacted all aspects of the economy. Banks began to close and many Americans lost their savings while they saw their incomes, on average, plummet by 1/3 in the first years of the depression. Unemployment skyrocketed from 3% in September of 1929 to as high as 33% by 1932. The bottom had fallen out of the economy.

In the first years of the Great Depression, President Herbert Hoover took a hands-off approach. Convinced that large-scale, direct federal government aid would prove detrimental in the long run, he believed that aid from volunteer organizations would prove sufficient while the market corrected itself and stabilized the economy. But as the economic devastation worsened and Americans struggled, Hoover’s insufficient response brought wide-spread ridicule. Shanty towns propped up across the nation and became known as Hoovervilles. Frustrated Americans began calling empty pockets turned inside-out Hoover flags. Then, in the summer of 1932, Hoover ordered the military to remove World War I veterans from a make-shift camp they had established in Washington D.C. while they petitioned the government for early payment of bonuses promised for their previous military service. The eviction turned violent and the spectacle of the military forcibly removing veterans and torching their camp sealed Hoover’s fate. The following November, he lost his bid for reelection by a landslide to Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Franklin Roosevelt went on to become one of the most consequential presidents of the 20th century. Re-elected in 1936, 1940, and 1944, he led the country not only through the Great Depression, but also through most of World War II. He died in office during the Spring of 1945, just weeks before Germany surrendered and months before Japan followed suite – ending the world’s most cataclysmic military conflict.

Upon entering office in March of 1932, Roosevelt immediately led the federal government in a far more active role in addressing the economic devastation brought on by the Great Depression than had Hoover. The Roosevelt Administration dubbed its domestic agenda the “New Deal,” and organized it around the “Three R’s”: Relief – programs created to provide immediate assistance to those devastated by the Great Depression, Recovery – temporary programs and agencies created to re-start the economy, and Reform – permanent federal programs to protect Americans from future economic down-turns. From the beginning of his presidency, Roosevelt consistently addressed the nation over the radio in a series of “fireside chats,” that he used to reassure and inform Americans about the economic crisis and what the government was doing to address it. The radio addresses proved effective and brought a sense of national community in the face of the crisis by personalizing the president and his administration’s policies.

The most immediate crisis Roosevelt faced was that of failing banks. As the economic uncertainty increased, Americans panicked and rushed to their banks to withdraw the entirety of their savings. Because banks invested deposits elsewhere and did not keep 100% of the money deposited on hand, they quickly ran out of currency. By the time Roosevelt took office more than 5,000 banks had closed and countless Americans had lost their savings. On his second day in office, the new president declared a banking holiday, closed all federal banks, and rushed the Emergency Banking Act through Congress. The act took the nation off the gold standard, reorganized insolvent institutions, and rushed currency to banks with depleted cash reserves. After he explained the issue and solution to the American people over the radio, banks slowly reopened, and the country emerged from the immediate crisis.

Within 100 days of taking office the Roosevelt administration pushed 15 significant pieces of legislation through Congress aimed at providing governments-supported relief directly to citizens. Key programs of what became known as the First New Deal, are listed in table 11.1. Upon re-election in 1936, Roosevelt sponsored another flurry of legislation called the Second New Deal (see table 11.2).

TABLE 11.1

Key Programs from the First New Deal

| New Deal Legislation | Years Enacted | Brief Description |

| Agricultural Adjustment Administration | 1933–1935 | Farm program designed to raise process by curtailing production |

| Civil Works Administration | 1933–1934 | Temporary job relief program |

| Civilian Conservation Corps | 1933–1942 | Employed young men to work in rural areas |

| Farm Credit Administration | 1933-today | Low interest mortgages for farm owners |

| Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation | 1933–today | Insure private bank deposits |

| Federal Emergency Relief Act | 1933 | Direct monetary relief to poor unemployed Americans |

| Glass-Steagall Act | 1933 | Regulate investment banking |

| Homeowners Loan Corporation | 1933–1951 | Government mortgages that allowed people to keep their homes |

| Indian Reorganization Act | 1933 | Abandoned federal policy of assimilation |

| National Recovery Administration | 1933–1935 | Industries agree to codes of fair practice to set price, wage, production levels |

| Public Works Administration | 1933–1938 | Large public works projects |

| Resettlement Administration | 1933–1935 | Resettles poor tenant farmers |

| Securities Act of 1933 | 1933–today | Created SEC; regulates stock transactions |

| Tennessee Valley Authority | 1933–today | Regional development program; brought electrification to the valley |

SOURCE: Scott P. Corbett, et al., U.S. History (Houston: Open Stax – Rice University, 2017), 766.

TABLE 11.2

Key Programs from the First New Deal

| New Deal Legislation | Years Enacted | Brief Description |

| Fair Labor Standards Act | 1938–today | Established minimum wage and forty-hour workweek |

| Farm Security Administration | 1935–today | Provides poor farmers with education and economic support programs |

| Federal Crop Insurance Corporation | 1938–today | Insures crops and livestock against loss of revenue |

| National Labor Relations Act | 1935–today | Recognized right of workers to unionize & collectively bargain |

| National Youth Administration | 1935–1939 (part of WPA) | Part-time employment for college and high school students |

| Rural Electrification Administration | 1935–today | Provides public utilities to rural areas |

| Social Security Act | 1935–today | Aid to retirees, unemployed, disabled |

| Surplus Commodities Program | 1936–today | Provides food to the poor (still exists in Food Stamps program) |

| Works Progress Administration | 1935–1943 | Jobs program (including artists and youth) |

SOURCE: Scott P. Corbett, et al., U.S. History (Houston: Open Stax – Rice University, 2017), 775-76.

New Deal legislation did not solve the economic crisis Americans faced during the Great Depression. Some programs, such as the Civilian Works Administration (CWA), the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Public Works Administration (PWA), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), and the Work Progress Administration (WPA), worked well and provided employment to the unemployed in work benefitting the public good. Other programs were less effective and at times undercut the government’s ability to provide targeted relief to those who most needed it. In the end, the country’s entry into the second World War in late 1941 pulled it out of the economic crisis of the 1930s.

While federal government efforts to combat the suffering brought on by the Great Depression resulted in mixed results, Roosevelt’s New Deal significantly expanded the size and scope of the federal government and fundamentally changed its relationships with Americans. For the first time in American history, Americans came to believe that the federal government should play a role in providing for the nation’s most vulnerable citizens. Today our political parties disagree about how best to do this, and to what degree, but not over the belief that it falls to the federal government to do so.

Minnesota During the Great Depression

Section Highlights

- For Minnesota farmers, the depression started in the early 1920s and grew worse in the 1930s.

- The Minnesota Farm Holiday Association used a variety of methods to prevent farm foreclosures and encourage the state government to address farmers’ issues.

- In 1932 the state-wide unemployment was 29% but reached 70% on the Iron Range.

For Midwestern farmers, including those in Minnesota, the depression began long before the stock market crash in the fall of 1929. Spurred on by World War I demand that brought high prices, farmers expanded their production and took out loans to acquire labor-saving machinery. After the war ended and the immediate relief efforts concluded, demand fell, and prices plummeted (see table 11.3). The gross income of Minnesota farms fell from a 1918 high of $438 million to just $155 million in 1932. When the Great Depression spread to the rest of the economy in the early 1930s, demand fell even further – many farmers were unable to pay their taxes or meet loan payment obligations. Between 1922 and 1932, 2,866 Minnesota farms went bankrupt. In just six years between 1926 and 1932, 1,442 of the state’s farms were lost to foreclosure. To make matters worse ecological disasters between 1933 and 1934 – a drought and waves of grasshoppers – ravished famers in west-central Minnesota.[2]

GRAPH 11.3

Minnesota Farm Commodity Prices – 1914-1932

Source: Cameron, Linda A. “Agricultural Depression, 1920–1934.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/agricultural-depression-1920-1934 (accessed July 9, 2023).

As New Deal policy makers scrambled to help the agricultural sector with programs and agencies from Washington D.C., Midwestern farmers took matters into their own hands. In May of 1932, the president of the Iowa Farm Union, Milo Reno, established The National Farm Holiday Association (FHA) and began preparing for an agricultural strike wherein farmers would withhold their produce from the market to increase demand and raise prices. In late July of 1932 Kandiyohi farmer John Bosch founded the Minnesota branch of the FHA. Uncoordinated farmer strikes ran by local FHA branches took place in Iowa in August and in Minnesota in September of 1932. Although short-lived and violent at times, the strikes brought national attention to the famers’ plight and emboldened the FHA which began interfering in the farm foreclosure process. When attempts to negotiate with lenders and delinquent farmers failed, FHA members would sometimes physically block access to farm auctions. Alternatively, in what became known as “penny auctions,” FHA members coordinated to bid only pennies to purchase foreclosed farms only to return them to their original owners – with debts cleared. In March of 1933, the Minnesota FHA organized a march of 20,000 farmers on the state capitol in Saint Paul to advocate for state-level legislative help. That same year, however, an attempted nation-wide FHA strike failed when dairy farmers and corn growers disagreed on tactics and the organization lost much of its relevance.

By the early 1930s, the economic pain Minnesota farmers were feeling for more than a decade spread to the rest of the state. In 1932 unemployment hit 29% statewide and 70% on the iron range. Iron production that had constantly hit an annual rate of 33 million tons in the 1920s, dropped to just 2.2 in 1932. That same year, nearly 9 in ten Minnesota businesses operated at a loss. Bank closures also plagued the state throughout the 1930s – 320 state banks and 58 national banks closed during the decade. As Minneapolis’ Gateway District filled up with unemployed men, poverty was widespread and disheartening. Duluthian Raymond Noyes summed up the feeling of many when he recalled that “it was so degrading during the Depression for a man not to have employment. I had a brother and a sister besides myself, mother, and father. Five of us in the family. And, from day to day, we wondered where our next meal was coming from.”[3]

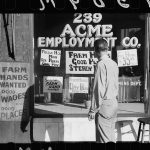

Depression-Era in the Gateway District of Minneapolis

During the Great Depression the Roosevelt Administration created the historical division within the Farm Security Administration. The FSA sent photographers across the nation to document the suffering of hard-working Americans in hopes of increasing support for New Deal relief programs. While the FSA dispatched most of the photographers to the rural areas of the South and Southwest, a selected few documented life in northern cities. Saint Paul native Gordon Parks famously made photographs in Washington DC. Photographers Russell Lee made photographs in Minneapolis in 1937 and John Vanchon photographed in the city in 1939. Here are a selection of FSA images from Minneapolis’ Gateway District in the late 1930s.

Click on the Images to expand them and use your browser’s back arrow to return to the text.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

During the summer of 1936 – over three years into President Roosevelt’s relief efforts – Minnesota still suffered and unrelenting heat seemed to make everything harder. In July Moorhead recorded a record high 114 degrees, while Duluth recorded numerous high temperatures above 100 degrees and the Twin Cities did so eight times in a nine-day stretch during the hottest weeks of the Month. The heat wave took the lives of 700 Minnesotans and 5,000 nation-wide. To make matters more difficult, the state’s popular Farmer Labor Governor, Floyd B. Olson, who was then serving a third term and polling well ahead in a senate race was critically ill with stomach cancer. He died the following August.[4]

The Farmer Labor Party at High Tide

Section Highlights

- Farmer Labor politician Floyd B. Olson was elected governor in 1930. He was reelected in 1932 and 1934 before his untimely death in 1936 while he was running for the senate.

- With Olson as governor, the Farmer Labor Party achieved a number of reforms, including: a progressive state income tax, unemployment insurance, pay equality for women, a minimum wage, expanded conservation programs, collective bargaining for unions, and a moratorium on farm foreclosures.

- In 1934 a truckers strike in Minneapolis turned violent.

- After Olson’s death the Farmer Labor Party lost much of its effectiveness.

- In 1938 Republican Harrold Stassen won the first of this three terms as governor and enacted policies of “enlightened capitalism.”

Floyd B. Olson’s three terms as governor denoted the high-water mark of Minnesota’s Farmer Labor Party (FLP). The Farmer Labor Party emerged in the early 1920s from within the Nonpartisan League – a grassroots political movement that connected discontented farmers with equally frustrated workers. Initially working from within the Republican Party, the FLP struck out on its own and replaced the Democratic Party as the primary rival to the Republicans. In 1922, it elected two senators and won a notable minority in the state legislature. With the state in the throes of the early stages of the Great Depression, Olson became the first FLP candidate to win the governor’s office in 1930 – a feat he repeated in 1932 and 1934. During his tenure in office, the Farmer Labor Party controlled the House, but never the senate and the governor proved adept at compromise and working with the Republican-held Senate. At the time of Olson’s untimely death in 1936, the Farmer Labor Party not only held the governorship, but also six out of Minnesota’s nine US congressional seats, and a comfortable majority in the Minnesota House of Representatives.

During his first term in office, Olson pursued a limited agenda that continued the moderation and pragmatism he showed during his campaign. By the time he won a second term in 1932 – in the same election that sent Franklin Roosevelt to the White House – the depression had worsened and frustrated Minneapolitans were protesting in the state’s largest city. Olson began his second term with a fiery inaugural speech that positioned his agenda well left of what Roosevelt was advocating in Washington. Despite a state senate controlled by conservative Republicans, the Olson-led Farmer Labor Party achieved fundamental reforms, including enacting a progressive state income tax, creating unemployment insurance, ensuring pay equality for women, establishing a minimum wage, expanding the state’s conservation programs, ensuring labor unions the right to collectively bargain, and placing a moratorium on farm foreclosures. Regardless of these notable successes, Olson was unable to achieve the more radical goals of the Farmer Labor Party that included state ownership of electrical utilities, iron mines, railroads, and meatpacking plants.[5]

During the 1930s, organized labor in Minnesota enjoyed support from the White House and the statehouse. In 1933, Hormel meatpacking workers in Austin, MN conducted the first successful sit-down strike in US history. In 1934, however, a truckers strike in Minneapolis turned violent and opened Olson’s measured response up to criticism by union officials.

In the Spring of 1934 Minneapolis Teamsters Local 574 struck to earn better wages, union recognition and the ability to organize warehouse workers. Their efforts bumped up against the Citizens Alliance – a powerful anti-union business organization that sought to keep unions out of Minneapolis. In late May a violent clash between strikers and Citizen Alliance “Special Deputies,” left two strikebreakers dead. After a tentative agreement brokered by Olson began to break down, the local renewed its strike in the middle of July and attempted to stop all truck traffic in the city. Four days after the renewed strike began, on what is now known as “Bloody Friday,” the police working closely with the Citizens Alliance opened fire on unarmed strikers, wounding 67 and killing two. In the wake of the violence and outrage that followed, outside mediators were brought in to broker a deal recognizing union demands, but one that the Citizens Alliance rejected. In response, Olson declared martial law and began issuing permits for certain trucking companies to bring essentials into the city. This led the Union Local president to declare that Olson was “the best strikebreaking force our union has ever gone up against” – not an enviable characterization for a Farmer Labor politician. Despite the criticism, Olson allowed only trucking companies that signed on to the agreement to bring trucks into the city, forcing the hold-out companies to reluctantly comply. By the end of August, all companies agreed to the pro-union brokered deal and the strike ended.

Olson’s untimely death in 1936 began an almost immediate decline in the political power of the Farmer Labor Party. It also cemented his reputation in Minnesota history. According to his biographer, George Mayer, “death enhanced Olson’s reputation because he died before political apathy and the increasing threat of war undermined the reforming zeal of the 1930s. As the lesser leftwing leaders who succeeded him wasted their energies in futile skirmishes, Olson’s faults were forgotten, and his achievements took on legendary proportions. Minnesota came to remember him as a fearless and effective crusader for social justice.”[6]

Among the most prominent of those lesser leaders was Elmer Benson who had the unfortunate distinction of being elected governor by the widest margin in 1936, only to lose in his re-election bid by another record margin in 1938 to the 31-year-old Republican Harold Stassen. Stassen easily won reelection in 1940 and again in 1942 before resigning to join the navy during World War II. An effective campaigner and administrator, Stassen preached “enlightened capitalism,” a Republican counter to the liberal reform movement embraced by the Farmer Laborers and the Democrats. He re-organized state government and sought to root out corruption and communism from Minnesota. The Farmer Labor Party never recovered from Olson’s death and Benson’s trouncing. In 1944 it merged with the Democratic Party to form the Democratic Farmer Labor Party (DFL) and in 1948 the more conservative wing of the DFL pushed out the more liberal leaning former Farmer Laborers. Today, Minnesota Democrats continue to use the DFL name more as a nod to the state party’s history than to separate itself from the national Democratic Party.

A New Deal in Minnesota

Section Highlights

- The Civilian Conservation Corps in Minnesota put young unemployed men to work in military-style regiment and completed over 150 projects the benefitted the public.

- African Americans in Minnesota faced discrimination in the CCC.

- The CCC-Indian Division completed projects important to indigenous communities.

- Part of Roosevelt’s Second New Deal, the Works Progress Administration invested $250 million in Minnesota to the benefit of 600,000 people.

- The WPA in Minnesota erected 1,443 bridges, built or improved 28,000 miles of roads, and constructed 1,324 public buildings, 52 grandstands, 119 athletic fields, 56 sewage plants, six swimming pools and three airports.

- The Federal Arts Project (FAP) and the Federal Writers Project (FWP) were part of the WPA in Minnesota.

- The Rural Electrification Administration (REA) used federal New-Deal funds to bring electricity to many rural Minnesotans.

In a general way, President Roosevelt’s relief efforts sought to put unemployed Americans to work developing infrastructure, producing goods, and providing services to benefit the public. To achieve this dual purpose, the New Deal created dozens of acts, agencies, and programs. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) were among the most prominent of these programs. All these agencies had a significant presence in Minnesota and much of their work is still visible and utilized by the public today.

The Civilian Conservation Corps in Minnesota

President Roosevelt established the Civilian Conservation Corps in March of 1933 – the same month he took office. The program aimed to put 250,000 unemployed young men to work on conservation and public park projects across the nation. The program was open to men between the age of 17 and 23, who were U.S. citizens, unmarried, unemployed, mentally and physically competent, and had finished high school. The men lived in camps, subject to military-style structure, schedule, and discipline. They earned $30 a month, of which $25 was sent home to their families.

In Minnesota, the federal government invested $84,900,000 and employed 77,224 men over the decade the corps existed (1933-1943). At the height of the program in 1935, 104 camps operated in the state – significantly more than the 54 Minnesota averaged over the span of the program. Work completed in the state was impressive and included:

- 156 completed projects

- 124 million trees planted

- Construction of 4,500 miles of roads

- Construction of 3,330 miles of fire breaks

- Stringing of 3,338 miles of rural telephone lines

- Provided 3.5 million days of labor for the US Forest Service and other forest-related work.

- Construction of dozens of state and national park structures across Minnesota.

Today it is not hard to see the work of the CCC across Minnesota. While roads, fire breaks, and telephone lines are more difficult to identify, the CCC work in the state’s parks are a visible reminder of the corps’ imprint on the state. The CCC rustic stone and log architecture are still present in Minnesota’s State Parks, including, but not limited to: Itasca, Flandrau, Jay Cooke, Interstate, Sibley, Scenic, Camden, Fort Ridgley, Monson, and Whitewater. Perhaps two of the state’s most prized CCC projects are at two of Minnesota’s most iconic parks: Gooseberry Falls on Lake Superior’s north shore and Lake Itasca – the source of the Mississippi River. At Gooseberry Falls State Park, CCC workers built, among other structures, a highway overpass near Castle Danger that mimics the façade of a castle. In addition, they constructed trails and stairs that still today lead visitors to the falls and their surroundings. At Itasca State Park, CCC work created the dam topped with steppingstones at the source of the Mississippi River. Today’s Park visitors can tip-toe across the Mississippi following a path laid by the CCC.[7]

While the CCC was open to both African Americans and indigenous Minnesotans, their opportunities and experiences differed markedly from white enrollees. The legislation creating the Corps prohibited discrimination, stating: “in employing citizens for the purposes of the Act, no discrimination shall be made on account of race, color, or creed.”[8] Regardless, all camps, including those in Minnesota, were run by the War Department and subject to the army’s segregation policies (The US military was not desegregated until 1948). Further, during the 1930s the Supreme Court 1896 ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson was still the law of the land and allowed for “separate but equal” accommodations (this did not change until the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision). All of this meant that African American enrollees in Minnesota CCC camps slept in segregated bunk areas and ate at separate tables. Since the work was done jointly, the US Army considered these camps nonsegregated or mixed.[9]

If segregated facilities could be rationalized as not technically violating the discrimination clause of the initiating CCC legislation, other realities could not. African American enrollees were not allowed to attend certain social events run by the camps, including dances and sporting events. Further, as the program grew, the War Department accepted fewer and fewer qualified African Americans into the Corps in Minnesota and nationwide. Then, in 1938 the existence of nonsegregated camps in the state came to an end when the War Department ordered all Minnesota African American CCC workers to be sent to segregated camps in Missouri. Loud protests from African American leaders and some politicians did little to change the situation. By the late 1930s, historian Barbara Somers noted, “the CCC administration and the army kept most qualified black enrollees out of the program and sent those few who did succeed in enrolling to camps in other states.”[10]

New Deal programs treated indigenous people differently than it did African Americans. The Indian Reorganization Act passed in 1934 sought, imperfectly, to reverse federally driven assimilation policies and made steps toward accommodating traditional indigenous concepts of landownership, culture, and governance. Working under that umbrella, the Indian Emergency Conservation Work program (IECW) began in June 1933 and later became known as the Civilian Conservation Corps – Indian Division (CCC-ID). While its enrollees did similar work, the CCC-ID was separate from the CCC and had some differences. First, being run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, enrollees were subject to less military-style regiment and discipline. There was also no upper age limit on acceptable candidates. Work camps were established on or near reservations and enrollees put to work on nearby projects important to local communities. Further, the CCC-ID offered vocational and academic courses from forestry to drama and history.[11]

In Minnesota, Ojibwe communities in the north and Dakota communities in the south participated and benefitted from the CCC-ID. In all, the federal government invested over $3 million in the state and the program reached over 2,500 of Minnesota’s indigenous families. Some of the most well-known and impactful projects completed by the CCC-ID included rebuilding the palisade at the Northwest Company’s old Grand Portage stockade and collecting fur-trade-era artifacts along the portage and at Fort Charlotte on the Pidgeon River side of the trail. This work began the process that eventually made Grand Portage and national historic monument. Crews also made wild ricing beds at Rice Lake more accessible by constructing log walkways, building docks, digging canals, and clearing campsites. In southern Minnesota, Dakota crews worked to enhance access to the Pipestone Quarry and laying the groundwork for that site’s national monument designation which came in 1937.[12]

The Works Progress Administration in Minnesota

On the eve of the 1936 election, President Roosevelt pushed Congress to pass a slate of additional relief measures that he dubbed the Second New Deal. Congress responded by, among other pieces of legislation, passing the Emergency Relief Appropriations Act that authorized the allocation of $4.8 billion to federally funded relief efforts. Out to that funding, the Roosevelt Administration established the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in May of 1935. The WPA sought to take unemployed Americans off direct public relief (the dole) and provide employment in shovel-ready projects that would benefit the public. While the most remembered division of the WPA was engaged in building public infrastructure – roads, bridges, airports, buildings, and other public works projects, the program also employed artists, writers, and musicians along with high school and college students. Between its establishment in 1935 and the program’s closure in 1943, the WPA employed 8.5 million Americans and built or improved 8,000 parks, laid 16,000 miles of water lines, and constructed 650,000 new or improved miles of roads. In addition, WPA workers produced 382 million articles of clothing and served 1.2 billion school lunches.[13]

Given the WPA’s massive scope, it is difficult to determine how many projects were completed and people employed in Minnesota. Nevertheless, architectural historian Rolf Anderson has suggested that the federal government invested over $250 million in WPA projects in the state, and in doing so provided benefits to nearly 600,000 people. Anderson estimates that the WPA erected 1,443 bridges, built or improved 28,000 miles of roads, and constructed 1,324 public buildings, 52 grandstands, 119 athletic fields, 56 sewage plants, six swimming pools and three airports. The results of these projects can still be seen in every corner of the state today, including: the Harriet Island Pavilion and Como Zoo buildings in Saint Paul, park features in Minnehaha and Theodore Worth Parks in Minneapolis, Hwy 101 in the western Minneapolis/St Paul metropolitan area, Wade Stadium in Duluth, Selke Field on the St Cloud State University Campus, and the Mahnomen County Fairgrounds. The WPA also assisted the CCC in their work at Gooseberry Falls. Furthermore, WPA workers built the scenic overlook in Mendota off highway 13 which continues to provide Minnesotans a majestic view of the Minnesota River and the Minneapolis/St Paul international airport just beyond. In a field near the overlook, a lone stone chimney is all that remains of the WPA camp that housed the workers who quarried the stone and constructed the park nearly 90 years ago.

Much of the WPA work, however, was less obvious and served to sustain and improve the urban infrastructure of Minnesota’s cities. In the state’s largest city, historian Iric Nathanson noted that “by 1942, the WPA in Minneapolis had paved 60 miles of streets, curbs and gutters; installed 64,000 traffic signs, built 313,000 feet of sewers; and reconditioned 113 public schools”[14]

While the iconic image of the WPA construction worker and the built environment the work crews left behind are perhaps our most vivid memory of the WPA, the program included a “cultural” side too. Two of the most prominent cultural programs included: the Federal Arts Project and the Federal Writers Project. Both left an impact on the state.

According to historian Katherine Goertz, The Federal Arts Project (FAP) in Minnesota sought not only to fund public art, but also “to promote and support art education, to produce research in art, and to focus on how art could serve Minnesota communities.” To reach these objectives, the FAP employed hundreds of artists across the state to create paintings, sculptures, photographs, prints, posters, and murals. Minnesota FAP artists focused on Americana and painted Minnesotans farming, mining, milling, and working in factories. They also produced imagery of indigenous Minnesotans along with cityscapes and rural scenes – some as murals to adorn public buildings. FAP artist also taught low-cost courses in St Paul, Minneapolis, and Duluth. In Minneapolis, FAP artists worked to establish the Walker Art Center – which continues to serve the community as a nationally respected art museum.

The Federal Writers' Project (FWP) employed around 120 authors across the state. While the program faced challenges over unwanted editorial direction from the federal government, organized writers who threatened to strike, and turn-over in its leadership, it did produce several publications that honored the state’s history and culture. Most prominent was the 1938 publication of Minnesota – A state Guide. Now known as the WPA Guide to Minnesota, the comprehensive volume was part of a national state series and provided a historical and cultural overview of Minnesota along with descriptions of suggested auto and city tours of various places across the state. In addition, Minnesota FWP writers also published more focused studies – most notably, The Minnesota Arrowhead Country and an ethological study of Bohemian Flats in Minneapolis. While many unemployed writers were happy to have the work, others were disappointed with the low pay and what they considered trivial assignments. Among the most prominent of Minnesota authors employed by the FWP was Frances Densmore who was in the middle of a life-long career that produced 20 books, 200 articles, and captured over 2,500 recordings of indigenous music – including that of the Dakota and Ojibwe.

The Rural Electrification Administration in Minnesota

In May of 1935, President Roosevelt created the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) through Executive Order 7037. Although there were a spattering of cooperatives and programs that brought electricity to a handful of farms in Minnesota in the 1920s, for the most part farmers and other Minnesotan living in rural areas went without access to electricity. The high costs of building power plants and electrical lines to service a spread-out rural population made rural electrification unattractive to private companies. As a result, by 1934, although most Minnesotans living in urban areas had access to electricity and the conveniences it brought, less than 7% of farms had central-station electrical service. To address this inequality, the REA sought to provide electrical service to rural Americans by providing low-interest loans to subsidize the construction of power plants, stringing of power lines, wiring homes and farms, installing indoor plumbing, and purchasing electrical machines and household appliances.

Even after the federal government established the REA, power companies were still reluctant to extend service to rural Minnesotans. To overcome this obstacle, Minnesota farm communities by-passed them and began forming cooperatives to access REA funding and administer the process of electrification. The first REA funded cooperative, the Meeker Cooperative Light and Power Association (MCLPA), was organized in September of 1935 and began providing electricity to just under 700 farms in late 1936. By 1940, mostly because of REA-funded cooperatives, 30% of Minnesota farms had access to central-station power. Earlier that year, Congress made the REA a permanent agency that operated until 1994. By the early 1960s, 99% of American farms had electricity – in no small part due to the REA.

Conclusion

Like many Americans, Minnesotans struggled and faced daunting challenges during the Great Depression. They also showed endurance and elected perhaps the country’s most liberal governor in Floyd B. Olson that resulted in significant state-level reforms enacted in the face of depression-era difficulties. Minnesotans also took advantage of federal New Deal programs that provided direct relief and resulted in projects that continue to be enjoyed and utilized today. These reforms and programs, although helpful, did not provide a final definitive answer for the economic challenges of the 1930s. Instead, the American entrance into World War II in December of 1941 retooled the economy and laser focus the generation on a different and perhaps even more daunting challenge.

The Living New Deal in Minnesota

Here is a web site that provides information about New Deal Programs in Minnesota. You can use the interactive map to learn about programs near your city.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Cameron, Linda A. . “Civilian Conservation Corps in Minnesota, 1933–1942 .” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/civilian-conservation-corps-minnesota-1933-1942 (accessed July 7, 2023).

Cartwright, R. L.. “Farmers’ Holiday Association in Minnesota.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/farmers-holiday-association-minnesota (accessed July 7, 2023).

Nathanson, Iric. “Olson, Floyd B. (1891–1936).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/olson-floyd-b-1891-1936 (accessed July 7, 2023).

O’Connell, Tom. “Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party, 1924–1944.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/minnesota-farmer-labor-party-1924-1944 (accessed July 7, 2023).

Saylor, Thomas. Remembering the Good War: Minnesota’s Greatest Generation. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005.

Sommer, Barbara W. Hard Work and a Good Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2008.

Sturdevant, Lori. “Politics in Minnesota .” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/politics-minnesota (accessed July 7, 2023).

- Tom Brokaw, The Greatest Generation (New York: Random House, 1998), cover flap. ↵

- Cameron, Linda A. . "Agricultural Depression, 1920–1934." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/agricultural-depression-1920-1934 (accessed July 9, 2023). ↵

- Barbara Sommer, Hard Work and a Good Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Minnesota. (Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul, Minn., 2008), 12. ↵

- Mark Steil, “Summer of 1936 brought heat, grief to Minnesota,” Duluth News Tribune, July 23, 2016. Available as of July 9, 2023 online at: Summer of 1936 brought heat, grief to Minnesota - Duluth News Tribune | News, weather, and sports from Duluth, Minnesota ↵

- William Lass, Minnesota: A History – Second Edition (New York: Norton, 1998), 223-26. ↵

- George Mayer, The Political Career of Floyd B. Olson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1951), 301. ↵

- Barbara Sommer, Hard Work and a Good Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Minnesota (Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2008), 99-108. ↵

- Sommer, Hard Work and a Good Deal, 23. ↵

- Sommer, Hard Work and a Good Deal, 23, 55. ↵

- Sommer, Hard Work and a Good Deal, 26. ↵

- LaFontaine, Harlen. "Civilian Conservation Corps-Indian Division." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/civilian-conservation-corps-indian-division (accessed July 12, 2023); Somers, Hard Work and a Good Deal, 26-27. ↵

- Somers, Hard Work and a Good Deal, 130-31; LaFontaine, Harlen. "Civilian Conservation Corps-Indian Division." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/civilian-conservation-corps-indian-division (accessed July 12, 2023). ↵

- Corbett, US History, 773-74; Lisa Thompson, “The Works Progress Administration (1935)” The Living New Deal. Available online as of August 6, 2023 at Works Progress Administration (WPA) (1935) - Living New Deal. ↵

- Iric Nathanson, “The WPA in Minnesota: economic stimulus during the Great Depression,” MINNPOST, Jan 7, 2009. ↵

Minnesota farmers enjoyed a period of prosperity in the 1910s that continued through World War I. Encouraged by the US government to increase production, they took out loans to buy more land and invest in new equipment. As war-torn countries recovered, however, the demand for US exports fell, and land values and prices for commodities dropped. Farmers found it hard to repay their loans—a situation worsened by the Great Depression and the drought years that followed.

Linda Cameron, MNOpedia Agricultural Depression, 1920–1934 | MNopedia

Founded in 1932, the short-lived Farmers' Holiday Association (FHA) is remembered for successfully fighting against farm foreclosures. The FHA also unsuccessfully lobbied Congress for a federal system that would pay farmers for their crops based on the cost of production.

-R. L. Cartwright, MNOpedia Farmers' Holiday Association in Minnesota | MNopedia

The Gateway District was Minneapolis’s original downtown, where life revolved around mills and railroads. As aging buildings became boarding houses for the thousands of temporary workers who spent their off-seasons in Minneapolis, the neighborhood gained a seedy reputation and the nickname “Skid Row.” The twenty-five-block zone was targeted for decades by mission workers, city planners, and police as a hub of vice and firetrap buildings, but the redevelopment of the area failed to mitigate its decline after World War II.

-Samuel Meshbesher, MNOpedia Gateway District (“Skid Row”), Minneapolis | MNopedia

As Minnesota's first Farmer-Labor Party governor, Floyd B. Olson pursued an activist agenda aimed at easing the impact of the Great Depression. During his six years in office, from 1931 to 1936, he became a hero to the state's working people for strongly defending their economic interests.

-Iric Nathanson, MNOpedia Olson, Floyd B. (1891–1936) | MNopedia

Minnesota's Farmer-Labor Party (FLP) represents one of the most successful progressive third-party coalitions in American history. From its roots in 1917 through the early 1940s, the FLP elected hundreds of candidates to state and national office and created a powerful movement based on the needs of struggling workers and farmers.

Tom O'Connell, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/minnesota-farmer-labor-party-1924-1944

“No trucks shall be moved! By nobody!” was the rallying cry of Minneapolis Teamsters Local 574 as they struck in the summer of 1934. Their demands were clear: a fair wage, union recognition, and the trucking firms’ recognition of inside workers as part of the union. Despite the violent reaction of the authorities, the 574 won on all these points.

-Eshan Alam, MNOpedia Minneapolis Teamsters’ Strike, 1934 | MNopedia

Elmer Benson was elected in 1936 as Minnesota’s second Farmer-Labor Party governor with over 58 percent of the vote. He was defeated only two years later by an even larger margin. An outspoken champion of Minnesota’s workers and family farmers, Benson lacked the political gifts of his charismatic predecessor, Floyd B. Olson. However, many of his proposals—at first considered radical—became law in the decades that followed.

-Tom Oconnell, MNOpedia https://www.mnopedia.org/person/benson-elmer-1895-1985

During a lifetime devoted to public service, Harold Stassen left an indelible mark upon American politics. He first gained national prominence in the 1930s by revitalizing Minnesota’s Republican Party and establishing a progressive, cooperative approach to state government. Although his achievements are often obscured by his seemingly relentless quest to become president, Stassen contributed greatly to the cause of international peace following World War II.

-Steve Werle, MNOpedia Stassen, Harold (1907–2001) | MNopedia

The U.S. Congress paved the way for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) when it passed the Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) Act in March 1933, at the height of the Great Depression. This New Deal program offered meaningful work to young men with few employment prospects. It resulted in a lasting legacy of forestry, soil, and water conservation, as well as enhancements to Minnesota's state and national parks.

-Linda Cameron, MNOpedia Civilian Conservation Corps in Minnesota, 1933–1942 | MNopedia

One of Minnesota’s most popular nature areas, Gooseberry Falls was the first of eight state parks developed along Lake Superior’s North Shore. Nearly all of its buildings were constructed by employees of the Civilian Conservation Corps between 1934 and 1941. The collection of stone and log structures presents a distinctively North Shore interpretation of the National Park Service’s Rustic Style of architecture, complementing the park’s river, waterfalls, woodlands, and lakeshore.

-Marjorie Savage, MNOpedia Gooseberry Falls State Park | MNopedia

The Itasca forest during the late nineteenth century contained towering pines and numerous lakes. Individuals like surveyor Jacob Brower became captivated by the region and the wildlife that inhabited it. They recognized that the economic potential of northern Minnesota would change its landscape. Their effort to preserve Lake Itasca led them to contend with the lumber industry, public interests, and the politics that weaved between them.

-Steven Penick, MNOpedia https://www.mnopedia.org/event/creation-itasca-state-park

Between 1933 and 1943, Native Americans worked on their lands as part of the Civilian Conservation Corps-Indian Division, run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). More than 2,000 Native families in Minnesota benefited from the wages as participants developed work skills and communities gained infrastructure like roads and wells.

-Harlen LaFontaine and Margaret Vaughan, MNOpedia Civilian Conservation Corps-Indian Division | MNopedia

The Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project was a New Deal relief program to fund the visual arts. From 1935 to 1943, the Minnesota division of the FAP employed local artists to create thousands of works in many media and styles, from large works of public art to posters and paintings.

-Katherine Goertz, MNOpedia WPA Federal Art Project, 1935–1943 | MNopedia

At the height of the Great Depression, nearly one in four Americans was unemployed. Under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the federal government created the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to employ millions of jobless Americans. The WPA hired men and women to do white collar work like writing, as well as manual labor and construction. In Minnesota, the WPA's Federal Writers' Project was marked by controversy and tension with the federal government, but it created state guidebooks and ethnic histories that are still read widely today.

-R.L. Cartwright, MNOpedia https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/wpa-federal-writers-project-1935-1943

From the 1890s through the 1950s, Frances Densmore researched and recorded the music of Native Americans. Through more than twenty books, 200 articles, and some 2,500 Graphophone recordings, she preserved important cultural traditions that might otherwise have been lost. She received honors from Macalester College in St. Paul and the Minnesota Historical Society in the last years of her life.

-Frederick L Johnson, MNOpedia Densmore, Frances (1867–1957) | MNopedia