8 Statehood and Civil Wars: Transition and Crisis

The national quest for Manifest Destiny encouraged Minnesota’s territorial push in the late 1840s, but less than a decade later, when Minnesota began moving toward statehood, the national political climate complicated the process and made it far more difficult. Since the 1820s, growing sectionalism between the industrial states in the North closed to slavery, and the agricultural states in the South dependent on slavery, had resulted in a concerted effort to keep the number of free and slave states equal. Politicians hoped that the resulting sectional equality in the Senate would allow each region to have its interests protected and permit the national government to survive the increasing polarization.

The balancing act worked for a while and to a point, but the territory added to the Union during the 1840s had pushed the nation to a breaking point. In December of 1845, the United States annexed Texas, then the northern province of Mexico that had declared its independence nine years earlier. The annexation in general and a border dispute in particular led to war between the United States and Mexico that began in the Spring of 1846. At the war’s conclusion in early 1848, the United States acquired what is today the southwestern portion of the nation. Additionally, during the summer of 1846, the U.S. had negotiated an agreement with Great Britain over disputed territory in the Pacific Northwest that brought what is today Oregon into the nation. In short, the territorial gains between 1845 and 1848 increased the size of the United States by some 70%. The challenge of incorporating these new territories into the nation while balancing the interests of free vs. slave states became the test of the 1850s.

The Compromise of 1850 brought California into the nation as a free state and patched together a host of other compromises that left no one happy. In 1854, the decision to allow the question of slavery to be settled locally in Kansas ended in disaster and open bloodshed. Among a long list of other events that further pushed the sections apart, the Dred Scott Decision – a case coming out of Minnesota – played its part in the growing rift. An attempt to bring both a free state of Minnesota and a slave state of Kansas into the union together faltered when Kansas deteriorated into a low-level civil war. By 1858, when Minnesota was admitted to the Union as a free state, Congress had all but abandoned the idea of keeping a balanced number of slave and free states. Because the 1850 admission of California gave free states a one-state advantage in the Senate (16 to 15), and free states had larger populations and therefore controlled the House of Representatives, Minnesota was eventually admitted to the Union as the 32nd state in 1858.

Balancing States Open to Slavery with Those Closed to Slavery

- 1837

- 1846

- 1850

- 1858

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

While Minnesotans struggled to address internal differences around statehood, the nation descended into the Civil War. Seven states in the Deep South withdrew from the Union when Republican Abraham Lincoln won the election to the presidency in 1860. After South Carolina attacked the federal garrison at Fort Sumter in 1861, six additional slave states from the Upper South left the Union and joined the Confederacy. With war declared, Minnesota proudly became the first state to offer troops to the Union cause. The Minnesota First Volunteer Regiment, along with other Minnesota regiments, went on to play a crucial role in the devastating four-year conflict.

While no Civil War battles were fought in Minnesota, the war certainly impacted daily life in the state. To make matters exceedingly more distressing, inept federal American Indian policies coupled with incompetent decision-making led to a devastating war between factions of the Dakota people and the U.S. government that erupted in southern Minnesota during the summer of 1862.

Manifest Destiny of the 1840s and the Sectional Crisis of the 1850s

MANIFEST DESTINY OF THE 1840s

- 1845: Texas is annexed and becomes the 28th state (open to slavery)

- 1846: The Oregon border dispute with Great Britain is settled

- 1846: Iowa becomes the 29th state (closed to slavery)

- 1848: Wisconsin becomes the 30th state (closed to slavery)

- 1848: Territory in the South and West Coast added to the union at the conclusion of the Mexican American War

- 1849: Minnesota becomes a territory

SECTIONALISM OF THE 1850S

- 1850: Compromise of 1850 – California becomes the 31st state (closed to slavery)

- 1852: Uncle Tom’s Cabin published

- 1854: Kansas-Nebraska Act applies “popular sovereignty” to the slavery question

- 1854: After the demise of the Whig Party, the Republican Party is founded

- 1855: Bloodshed over the slavery question begins in Kansas and becomes known as “Bleeding Kansas”

- 1856: Charles Sumner, an abolitionist Senator, is caned by Preston Brooks

- 1856: Dred Scott Decision

- 1858: Lincoln-Douglas Debates

- 1858: Minnesota becomes a state

- 1859: John Brown attacks Harper’s Ferry, Virginia

- 1860: Republican Abraham Lincoln elected President of the United States

- 1860-1861: Southern states secede, 1860-61

- 1861: The Confederate States of America established

- Federal garrison at Fort Sumter attacked by South Carolinian forces

- 1861: Civil War begins

Statehood

Section Highlights

- The national debate over slavery complicated Minnesota’s quest for statehood during the 1850s.

- Democrats led by Sibley and Republicans led by Ramsey each met separately during the convention and drafted separate constitutions.

- The shape of the state and the political status of African Americans were the two most contentious issues discussed at the convention.

- The Constitution did not provide voting rights for African Americans.

- Over southern objections, Minnesota became the 32nd state on May 11, 1858.

The ability to play a more active role in the contentious national political debate, exert more local control over taxation and government policy, and attract more governmental investment in railroad construction and infrastructure development all encouraged Minnesotans to pursue statehood in the latter half of the 1850s. The path to statehood, however, was marred with difficulties both nationally and locally. On December 24, 1856, Minnesota’s territorial representative introduced an enabling act in the House that would authorize Minnesota to begin the process of preparing for statehood by writing a state constitution and forming a state government. Passing the House, the bill moved on to the Senate where it endured a protracted debate over a provision allowing people in the process of becoming US citizens (but not yet US citizens) the ability to vote for delegates to the state constitutional convention as well as the political ramifications of adding another state closed to slavery to the Union. Over the dissenting votes of 22 southern senators, the Minnesota Enabling Act passed the Senate and became law on February 26, 1857.

The passage of the Enabling Act allowed Minnesota to hold a convention to draft a state constitution and elect state officeholders. Throughout the early territorial period, political affiliation did not matter much, but the unfolding national crisis changed that as Minnesota prepared for its convention. The Kansas-Nebraska Act and the subsequent bloodshed over slavery in Kansas had destroyed the Whig Party and undermined the national unity of the Democratic Party. In the void left by the demise of the Whigs, the Republican Party emerged in the North with the primary goal of stopping the spread of slavery into the territories. In the South, the pro-slavery southern wing of the Democratic Party held near total control. In Minnesota, Democrats led by Henry Sibleyand Henry Rice (who seemed to ignore the whole slavery issue) had a bit more support than the growing Republican Party led by the former Whig Alexander Ramsey.

The convention got off to a stumbling start when it opened in July of 1857. The election of delegates was hotly contested, and the results were extremely close. So close, in fact, that when an error sent 30 additional delegates to the convention, it became unclear which party had more legitimate support and should therefore be in control of the proceedings. Unable to reach a comprise, the two parties met separately and each created a draft constitution. Separately, they both dealt with two primary issues: the shape of the state and the status of African Americans within it. Interestingly, both conventions came to similar conclusions.

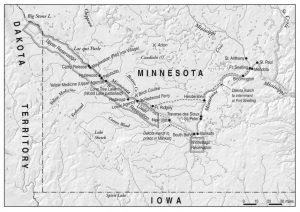

The enabling legislation defined a tall skinny state that set the international border as its northern boundary, Iowa as its southern boundary, and spanned from the Mississippi and Saint Croix rivers in the east to the Red River in the west. A second proposal discussed in both conventions, but finding more support with the Republicans, was for a shorter, fatter state with its western border at the Missouri River and its northern border just north of Saint Paul. This second proposal also included a failed attempt at relocating the state capitol from Saint Paul to Saint Peter. In the end, both delegations agreed to a taller, skinnier state – and, after some political shenanigans, the capitol remained in Saint Paul.

A more contentious issue was of a national origin and had to do with the status of African Americans in the new state. Indeed, several weeks before the conventions opened the St. Paul Pioneer and Democrat declared the most crucial question to be answered at the convention pitted “White Supremacy against Negro Equality!”[1]

While Minnesota never contemplated legalizing slavery in its constitution, the Republican convention did debate whether the franchise – the right to vote – should be extended to African American men. In the end, fear that doing so might derail the constitution’s ratification in the US Congress convinced Republicans to join the Democrats in leaving the provision out. Having developed similar documents and understanding that the dueling conventions made Minnesota look silly, the factions agreed to compromise by incorporating some Republican suggestions into the Democratic version of the constitution before sending it on to Congress. State-wide elections put the legislature in Democratic control, and Democrat Henry Sibley narrowly defeated Republican Alexander Ramsey to become the state’s first governor.

Although ready by early 1858, Minnesota’s quest for statehood bogged down in Congress as the nation watched the situation in Kansas continue to descend into chaos. After a four-month delay and over southern opposition, Minnesota received congressional approval on May 11, 1858, and became the nation’s 32nd state.

Minnesota and the Civil War

Section Highlights

- The Minnesota First Volunteer Regiment was the first to be offered to defend the Union during the Civil War.

- Approximately 25,000 Minnesotans fought for the Union during the Civil War – 2,500 died in battle or due to sickness. A far larger number were wounded physically or mentally by the war.

- The Minnesota First played a crucial role in the Union Victory at Gettysburg in July 1863.

- The Minnesota Third, Fourth, and Fifth Regiments played a critical role durring the capture of Vicksburg on July 4th, 1863

- Gettysburg and Vicksburg – both Union victories won during the first four days of July 1863 – were a turning point in the war.

In November of 1860, the country elected Republican Abraham Lincoln as the 16th President. Lincoln won the presidency without even being on the ballot in the southern states that were then outnumbered by northern states closed to slavery by 18 to 15 (Oregon had been admitted in 1859). Believing that their interests could not be served by a government controlled by states hostile to slavery, South Carolina left the Union in December. By February 1861, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had also departed and joined South Carolina in forming the Confederate States of America. Just over a month after Lincoln was inaugurated in March, South Carolinian forces attacked a federal garrison at Fort Sumter and forced its surrender. After fighting had commenced, six additional slave states from the upper south – Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, Missouri, and Kentucky left the Union and joined the Confederacy. Just three years after Minnesota had joined the union, the nation had tragically splintered into two, and what was left of the United States was determined to make it whole again. Patriotism ran high in Minnesota, and the new state quickly pledged itself to do its part in repairing its nation.

Memorial to the Union Soldiers and Sailors of the War of 1861-1865

The “Soldiers and Sailors” monument sits adjacent to the Saint Paul College campus across Summit Avenue. The inscription reads in part: “To perpetuate the memory of the Union Soldiers and Sailors of the war of 1861-1865. Their patriotism inspired unquestioning devotion – Their valor was attested on hard-won battlefields – Their suffering and sacrifice exalted the glorious cause and ennobled the splendid triumph.” Erected in 1903, the “statue represents Josias R. King the first man to volunteer in the first Minnesota Infantry Regiment tendered to the government for the suppression of the rebellion.” Recently, researchers uncovered that Josias King “also participated in violent campaigns to punish Dakota people after the US-Dakota War of 1862, known as the Punitive Expeditions. These included the Massacre of White Stone Hill, in which the US military killed hundreds of Native men, women, and children. King’s participation in the massacre has complicated his presence in the monument.”[2]

The “Soldiers and Sailors” monument sits adjacent to the Saint Paul College campus across Summit Avenue. The inscription reads in part: “To perpetuate the memory of the Union Soldiers and Sailors of the war of 1861-1865. Their patriotism inspired unquestioning devotion – Their valor was attested on hard-won battlefields – Their suffering and sacrifice exalted the glorious cause and ennobled the splendid triumph.” Erected in 1903, the “statue represents Josias R. King the first man to volunteer in the first Minnesota Infantry Regiment tendered to the government for the suppression of the rebellion.” Recently, researchers uncovered that Josias King “also participated in violent campaigns to punish Dakota people after the US-Dakota War of 1862, known as the Punitive Expeditions. These included the Massacre of White Stone Hill, in which the US military killed hundreds of Native men, women, and children. King’s participation in the massacre has complicated his presence in the monument.”[2]

Alexander Ramsey, having been elected the second governor of Minnesota in 1860, happened to be in Washington when news of Fort Sumter’s attack reached the city. He quickly offered the federal government 1,000 Minnesota troops, making Minnesota the first state to offer troops in defense of the Union. The regiment that formed to fulfill Ramsey’s pledge, the First Minnesota Volunteer Regiment, was just the beginning of the state’s commitment. By the war’s conclusion, Minnesota contributed 11 infantry regiments, three cavalry regiments, three artillery regiments, two companies of sharpshooters, and a regiment of rangers. Of the 25,000 men Minnesota sent to fight in the war, 2,500 were lost in battle or to illness – a far larger number returned physically and/or mentally wounded. According to historian Richard Moe, Minnesotans “did their part and more. They were among the first northerners to enlist, among the first to see combat, among the most battle-tested, among the most honored. They fought from the first battle at Bull Run to the final surrender at Appomattox Court House. They shed their blood at Shiloh, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, and Nashville, and there are monuments to their courage and sacrifice at each of those places.”[3] It is therefore fitting, perhaps, that a Minnesotan is credited with being the last surviving member of the Union army. Albert Woolson, who had served as a drummer boy in the First Minnesota Heavy Artillery, lived to be 109 before passing away in Duluth in 1956.

The First Minnesota

Of all the Minnesota Regiments, the First Minnesota Volunteers were the most honored and remembered. Just two weeks after Ramsey’s April 13th, 1861 commitment, 1009 Minnesotans from Saint Paul and surrounding communities were mustered into the U.S. Army at Fort Snelling. Quickly taught how to march together, clad in red flannel hunting shirts, black pants, and black wide-brimmed hats, the troops were sent by steamboat and then train to the East. By early July, they were stationed in Alexandria, VA. Before the month was out, and several months before they were to be issued their Union blue uniforms, they saw their first action.

The first major engagement of the war, the Battle of First Bull Run, took place outside Washington, D.C. On July 21, 1861. The battle resulted in a stunning Union defeat and shattered the country’s perception of a quick and relatively easy conflict ahead. While a disaster for the Union, the Minnesota First distinguished itself during the fighting. It had traveled the furthest of any unit in the engagement and found itself in the middle of the heaviest fighting. A twenty-year-old First Minnesota soldier from Hastings, Jasper Searles, recounted his experience at Bull Run in a letter he wrote to his “Friends at Home” just days later. Searles was proud of the showing the Minnesotans made for themselves during an otherwise dismal day. He recalled that the Minnesotans had to be “commanded to retreat three times before we obeyed.” Unlike most other units that broke and ran in disarray, the Minnesota First retreated in an orderly fashion that protected itself as it withdrew. Beyond pride, though, the letter also revealed a frustration with leadership that Searles felt allowed his regiment to be “marched up like sheep to the slaughter,” resulting in a 20% casualty rate that left 42 dead, 108 wounded, and 30 missing. Searles also, like many others in the wake of Bull Run, realized that “All ideas of having a short and easy conflict is past, and the people must prepare to meet the issue of events as they occur.”[4]

Attached to the Army of the Potomac in the Eastern Theater, the First Minnesota Volunteers built on the reputation it began to earn at Bull Run, but at an increasingly devastating cost in men lost. Over the next two years, the First fought at Balls Bluff, through the Peninsula Campaign, the Seven Days Battles outside of Richmond, and sustained 147 casualties at Antietam, MD in September of 1862 – the bloodiest single day of the war. By the summer of 1863, the First Minnesota Volunteers were massively understrength but were battle-tested and dependable.

The turning point of the war came during the first three days of July, 1863, when Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia met the Army of the Potomac, then commanded by George Meade, at the tiny Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg. On the second day of fighting, General Hancock ordered the First Minnesota into a breach in the Union line near Cemetery Ridge. Outnumbered by as many as four to one, the First stopped the Confederate advance long enough for reinforcements to plug the gap. The decisive charge saved the Union line, which had it broken would have changed the course of the battle and perhaps even the war. The costs, however, were devastating. Of the 262 men ordered into the breach, 215 were killed or wounded in a matter of 15 minutes. The nearly 85% casualty rate was the highest of the war, and earned the First Regiment the well-deserved reputation that follows it to this day.

Minnesota Remembers: Battle of Gettysburg – 1863

Immediately after Gettysburg, the First was sent to help quell the draft riots in New York City. Early in 1864, the First Minnesota Volunteer Regiment, its three-year enlistment ending, returned to Minnesota. On April 28, 1864, 16 officers and 309 enlisted men, all that remained of the 1009 men mustered into the army three years earlier, were decommissioned at Fort Snelling.

Minnesotans in the Western Theater

Outside of the First Minnesota’s attachment to the Army of the Potomac, all other Minnesota units saw action in the war’s western theater of operations. The Third Minnesota Volunteer Regiment,

for example, was mustered into service at Fort Snelling in October of 1861 and attached to the Army of the Ohio, then in Kentucky and Tennessee. The following July, the regiment suffered the embarrassment of being surrendered by its officers before it was given an opportunity to fight a smaller force under Confederate Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Paroled and sent back to Minnesota, a large contingent of the 3rd participated in the Battle of Wood Lake against the Dakota before being exchanged and allowed to return to the South.

The following July, the fortunes and reputation of the Third Minnesota improved greatly when the regiment participated in a successful siege of Vicksburg. Vicksburg, Mississippi, is located on the Mississippi River just above its exit into the Gulf of Mexico at New Orleans. In the summer of 1863, the city, situated on a bluff high above the Mississippi, was the final Confederate holdout on the strategically important river. President Lincoln himself placed a great deal of importance on the city, stating, “Vicksburg is the key – the war cannot be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.”[5]

In addition to the Third, other Minnesotans were part of U.S. Grant’s army that took Vicksburg, including the Minnesota Fourth and Fifth Infantry Regiments, along with the First Minnesota Battery of Light Artillery. Vicksburg fell on July 4, 1863 – just a day after Lee lost at Gettysburg. The combination of the two Union victories foreshadowed the downward trajectory of the Confederate cause, although the war was to grind on for more than a year.

In mid-December 1864, Much of Minnesota’s fighting force was at the last major engagement in the western theater – the Battle of Nashville. The Minnesota Fifth, Seventh, Ninth, and Tenth Infantry Regiments were joined by the Second Minnesota Light Artillery to play a major role in the Union victory that closed the western theater of action. Because so many Minnesotans were involved in the battle, it also gained the dubious distinction of resulting in 302 Minnesota casualties – the highest of any single battle of the war. Months later, in the Spring of 1865, Grant’s Army of the Potomac chased Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia out of Richmond and Petersburg and trapped it at Appomattox Court House. There on April 9th, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant, and for all practical purposes, the Civil War drew to a close. Less than a week later, on April 15, John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in Washington, and the country’s nightmare continued.

Minnesota Remembers: The Battle of Nashville – 1864

The U.S. Dakota War of 1862

Section Highlights

- In 1862, while the United States was fighting the Civil War, the U.S. Dakota War took place in southwestern Minnesota.

- A failed U.S. policy toward the Dakota combined with poor decision making by government agents created an atmosphere ripe for conflict.

- The murder of five settlers by four Dakota young men began the war.

- Many Dakota and people of mixed ethnicity did not participate in the fighting, and many aided Euro-American settlers.

- Both sides committed atrocities and there were victims on both sides.

- The Dakota war faction was defeated after six weeks of fighting.

- 38 Dakota were tried and sentenced to death in dubious post-war trials. On December 26, 1862, the U.S. government hung 38 Dakota men in Mankato, MN.

- During the winter of 1862-63 the Dakota people were imprisoned at an internment camp at Fort Snelling – as many as 300 died.

- The U.S. government took away Dakota reservations and cancelled annuity payments after the war.

- Most of the Dakota were sent to reservations west of Minnesota in the Spring of 1863

In the summer of 1862, with the country and state distracted by the Civil War, a disastrous federal Indian policy and short-sighted decision-making combined to bring a second war to southern Minnesota.

Failed Federal Policy

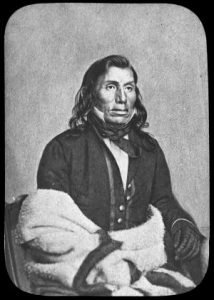

On the Dakota reservations established by the 1851 treaties, federal policy, assisted by well-intentioned but culturally biased missionaries, sought to assimilate the Dakota people by encouraging private land ownership, farming, and the adoption of white language, culture, and religion. These pressures served to divide the Dakota people into groups more resistant to change, called “Blanket Indians,” and those more willing to assimilate, called “Cuthairs” or “Farmer Indians.” The presence of a large number of people of mixed Euro-Dakota ancestry served only to complicate the situation, made increasingly more difficult by the government’s failure to make good on its treaty promises and to make prompt and complete annuity payments. When the US Government called Dakota leaders to Washington in 1858, the Dakota believed they were summoned to discuss shortcomings in treaty administration. Instead, government negotiators stranded the delegation in Washington for six weeks before using dubious tactics to induce the Dakota to relinquish the northern portion of their reservation. The leaders, including Little Crow, returned home with their credibility damaged and leadership undermined in the eyes of their people.

By the summer of 1862, the situation had grown desperate for the Dakota. Confined to a reservation ½ its original size, the Dakota had endured a harsh winter and watched as cutworms destroyed crops, waited for past-due annuity payments, and learned that the traders had cut off credit. The Dakota people were starving. Then, on August 17, in a show of bravado fueled by smoldering frustration over dismal conditions on their reservation, four young Dakota men murdered five settlers north of the reservation.

War

Just before dawn the following morning, a delegation of chiefs led hundreds of young men to Little Crow’s frame house on the Dakota reservation in the Minnesota River valley. Roused from sleep, Little Crow, an embattled Mdewakanton Dakota leader recently removed from any official leadership role, listened as the chiefs explained what had happened the day before.

As Little Crow sat in his bed with a blanket draped over his shoulders, the assembled chiefs discussed two courses of action. They could turn over the four murders to government authorities and endure punishment of unknown severity. Or, they could choose to rally the Mdewakanton Dakota and their sister bands in a general war against a US government distracted by its own Civil War. Little Crow joined Traveling Hail, Wabasha, and Big Eagle in advocating peace in opposition to Red Middle Voice, Young Shakopee (Little Six), and Medicine Bottle’s pleas for war. Young Shakopee argued, “blood had been shed, the payment would be stopped, and the whites would take a dreadful vengeance because women had been killed.” Little Crow seemed to be defusing the situation and turning the council toward reconciliation when Red Middle Voice declared that “Little Crow is afraid of the White Man; Little Crow is a coward!”

Little Crow’s son, who was in the room listening to the heated debate, recalled his father’s reaction. Throwing Red Middle Voice’s headdress to the floor, Little Crow countered: TA-O-YA-TE-DU-TA is not a coward, and he is not a fool! …

Braves, you are like little children; you know not what you are doing… Yes; they fight among themselves, but if you strike at them they will all turn on you and devour you and your women and little children just as the locusts in their time fall on the trees and devour all leaves in one day. You are fools. You cannot see the face of your chief; your eyes are full of smoke. You cannot hear his voice; your ears are full of roaring waters. Braves, you are little children – you are fools. You will die like the rabbits when the hungry wolves hunt them down in the Hard Moon. But after laying out his opposition to what he seemed to have felt was a hopeless situation, he added “Ta-o-ya-te-du-ta is not a coward; he will die with you.”[6]

Cheers of support filled the room and then poured out onto the grounds surrounding the house. The Mdewakanton Dakota would go to war, and Little Crow would lead them.

Before the war council concluded, Little Crow ordered an attack on the nearby Lower Sioux Agency to commence at daybreak. Big Eagle later recalled, “Parties formed and dashed away in the darkness to kill settlers.”[7] Shortly after dawn, Dakota soldiers attacked the agency, killing 21 civilians and government employees. By mid-morning, news of the attack had spread 13 miles to the east and reached Fort Ridgely, a small US military post garrisoned by just 76 men and two officers of Company B of the Minnesota Fifth Regiment. Captain John S. Marsh immediately set out for the Agency with 46 troops and marched directly into an ambush at the ferry crossing. Marsh lost ½ of his command and his life as he drowned attempting to swim the Minnesota River to escape the Dakota. By now, small groups of Dakota were murdering settlers, taking captives, and pillaging farms and settlements throughout the valley. When news of the hostilities reached the Upper Sioux Agency, a council of Wahpeton and Sisseton leaders was unable to agree upon a single course of action. While the majority opinion appeared to support joining the Mdewakanton, many leaders, including John Other Day and Paul Mazakutemani, the elected speaker of the Upper bands, refused and instead left the council to warn and aid settlers. Nightfall brought to a close a chaotic day that left the Dakota people and their Euro-Dakota relatives confused and fragmented, the settlers terrified, and over 200 civilians and US soldiers dead.

With the lack of a substantial military presence in the vicinity, settlers flocked to Fort Ridgely or the town of New Ulm. An unorganized Dakota effort to take New Ulm failed on August 19th, and the following days, soldiers and settlers successfully defended Fort Ridgely from a Dakota attack. On August 23rd, 650 Dakota soldiers again attacked New Ulm as settlers, now reinforced by militia units from surrounding communities, fiercely defended a three-block central perimeter as the rest of the town burned. But the 2,000 residents and refugees of New Ulm were now low on food, supplies, and ammunition and decided to flee to Mankato, some 30 miles to the east, the following day.

The Dakota lack of unity and the war faction’s failure to take Fort Ridgely or New Ulm proved critical as a relief force under the command of Col. Henry Hastings Sibley reached Fort Ridgely on August 28th. On the morning of September 2nd, a detachment of Sibley’s troops sent on a burial detail was surrounded and besieged for 31 hours at Birch Coulee. Sibley himself led a relief party that successfully lifted the siege midmorning of the following day, but not before enduring 60 casualties (13 dead; 47 wounded) and losing horses. On the same day, over 150 miles to the northwest, factions of Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota from the upper reservation attacked Fort Abercrombie on the Red River and then settled in for a three-week siege.

As September neared its end, however, the growing US military presence drained support from Little Crow’s war effort, and a peace faction of Dakota, always present, began to grow. The split became so severe that on several occasions, fighting nearly broke out between the peace and war factions of Dakota. Little Crow’s situation worsened when, on September 23rd, Sibley’s troops had unwittingly foiled a Dakota ambush attempt at Wood Lake. After about two hours of fighting, Little Crow’s forces withdrew in defeat, and most fled west into the prairies of the Dakotas. In their void, the Dakota peace faction took control of the 269 white and Euro-Dakota prisoners and arranged to deliver them to Col. Sibley on September 26th and 27th. At the same time, the army took 1200 mostly peaceful Dakota into custody. Over the following days, additional Dakota surrendered to Sibley, bringing the total of detainees to nearly 2,000.

Retribution

Within days of Little Crow’s exodus, Col. Sibley set up a five-person military tribunal to try Dakota men accused of murdering or assaulting civilians. By November 5th, the commission had tried 498 cases (some in as little as five minutes) and dispensed 303 death sentences in what was certainly a miscarriage of justice. The Lincoln Administration intervened and reduced the number of men sentenced to death to 39. After one additional reprieve, the largest mass execution in US history took place as 38 Dakota men were hanged together in Mankato on December 26, 1862. Little Crow, who had fled Minnesota after his defeat at Wood Lake, returned the following spring in search of horses. He was shot and killed by a farmer near Hutchinson on July 3, 1863, and his remains were brought back to St Paul and placed on public display.

Retribution was not confined to those convicted but extended to all Dakota, in most cases, regardless of the side they supported during the war. In November of 1862, the US army marched all detained Dakota people to Fort Snelling to spend the winter in an internment camp. Horrific conditions took the lives of as many as 300 people before the captives were exiled from the state the following spring.

Lower Sioux Agency Historic Site

With major fighting over in a matter of weeks, the US-Dakota War of 1862 left a wake of devastation, atrocities, and innocent victims on both sides. It has the dubious distinction of comprising what Gregory Michno has called “a massacre on a scale never before experienced by Americans” at its outset and the largest mass execution in US history at its conclusion.[8] It also proved to be an open salvo of an ongoing conflict that would soon spill west of Minnesota and take the country through the Great Sioux War (including Custer’s defeat at the Little Big Horn in 1876) and eventually the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890.

Conclusion

During the decade spanning the mid-1850s to the mid-1860s, Minnesota transitioned from a territory to a state, played a significant role in the US Civil War, and endured the devastating U.S. Dakota War. In many ways and for many people, the decade was filled with tragedy. The decade destroyed the lives of countless Dakota and Euro-American settlers in the Minnesota River Valley, and those soldiers lucky enough to return home from war often suffered from physical wounds and/or what was then called “soldier’s heart,” but today known as post-traumatic stress disorder.

For the Ojibwe forced onto reservations in the north and the Dakota, mostly expelled from the state and stripped of their reservations and land payments, the story moving forward from 1865 was one of endurance and resilience. For Euro-Americans who continued to flock into Minnesota to farm, cut down trees, and extract minerals from the ground, the story moving forward from 1865 was one of struggle and challenge.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Anderson, Gary, and Alan Woolworth, eds. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.

Carley, Kenneth. The Dakota War of 1862: Minnesota’s Other Civil War. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1961, 1976.

Carley, Kenneth. Minnesota in the Civil War: An Illustrated History. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2000

Moe, Richard. The Last Full Measure: The Life and Death of the First Minnesota Volunteers. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001.

Scher, Adam. “Long Remember: Minnesota at Gettysburg and Vicksburg.” Minnesota History (Summer 2013), 220-29.

The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Minnesota Historical Society. Accessed January 31, 2022. https://www.usdakotawar.org/.

- William Lass, Minnesota: A History of the State – 2nd edition (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1997), 124. ↵

- DeCarlo, Peter. "Soldiers and Sailors Memorial, St. Paul." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/thing/soldiers-and-sailors-memorial-st-paul (accessed February 7, 2022). ↵

- Carley, Kenneth, Minnesota in the Civil War: An Illustrated History. Forward by Richard Moe (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2000), xi. ↵

- Edward G. Longacre, ed. “‘Indeed We Did Fight’ A Soldier’s Letters Describe the First Minnesota Regiment Before and During the First Battle of Bull Run” Minnesota History (Summer, 1980), 67-70. ↵

- Adam Scher, “long Remember: Minnesota at Gettysburg and Vicksburg.” Minnesota History (Summer 2013), 224. ↵

- Gary Anderson and Alan Woolworth eds. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862 (Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988), 40. ↵

- Gary Anderson and Alan Woolworth eds. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862 (Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988), 36. ↵

- Gregory Michno, Dakota Dawn: The Decisive First Week of the Sioux Uprising, August 17-24, 1862 (New York: Savas Beatie, 2011), 2. ↵

The First Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment holds a special place in the history of Minnesota. It was the first body of troops raised by the state for Civil War service, and it was among the first regiments of any state offered for national service.

Hampton Smith, MNOpeida - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/first-minnesota-volunteer-infantry-regiment

Henry Hastings Sibley occupied the stage of Minnesota history for fifty-six active years. He was the territory's first representative in Congress (1849–1853) and the state's first governor (1858–1860). In 1862 he led a volunteer army against the Dakota under Ta Oyate Duta (His Red Nation, also known as Little Crow). After his victory at Wood Lake and his rescue of more than two hundred white prisoners, he was made a brigadier general in the Union Army.

Rhoda Gillman, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/sibley-henry-h-1811-1891

Designed to commemorate people who served in the US military during the Civil War, the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in St. Paul (sometimes called the Josias King Memorial) was erected in 1903. Crowning the monument is a statue of Josias R. King, who is widely regarded as the first US volunteer in the Civil War. King also participated in violent campaigns to punish Dakota people after the US–Dakota War of 1862, known as the Punitive Expeditions. These included the Massacre of White Stone Hill, in which the US military killed hundreds of Native men, women, and children. King's participation in the massacre has complicated his presence in the monument.

Peter DeCarlo, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/soldiers-and-sailors-memorial-st-paul

With the fall of Fort Sumter in 1861, Minnesota became the first state to offer troops to fight the Confederacy. Josias Redgate King is credited with being the first man to volunteer for the Union in the Civil War.

Brian Leehan, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/king-josias-r-1832-1916

The Third Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment's record of service varied greatly. The regiment endured a controversial surrender in Tennessee, played a decisive role in the climactic battle of the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862, and helped win Union control of the vital Mississippi River.

Matthew Hutchinson, MNOpeida - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/third-minnesota-volunteer-infantry-regiment

The Fifth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment's Civil War service included participation in thirteen campaigns, five sieges and thirty-four battles, including duty on Minnesota's frontier during the US–Dakota War of 1862. They were the last of the state's regiments to form in response to President Lincoln's first call for troops.

Matthew Hutchinson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/fifth-minnesota-volunteer-infantry-regiment

The Seventh Minnesota Infantry served on Minnesota's frontier in the troubled summer of 1862 and through the first half of 1863. The regiment eventually headed south, taking part in a key battle that virtually destroyed a major Confederate army. They also participated in one of the final campaigns of the war.

Matthew Hutchinson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/seventh-minnesota-volunteer-infantry-regiment

The Ninth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment played an important role in defending its home state as well as in operations in the South. Its three years of service for the Union culminated in the Battle of Nashville, in which its members fought side by side with men from three other Minnesota regiments.

Matthew Hutchinson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/ninth-minnesota-volunteer-infantry-regiment

By the summer of 1862, it was clear that the Civil War would not be over quickly. In July and August, President Lincoln called for several hundred thousand additional men to enlist for the Union cause. In response, the Tenth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment formed between August and November of that year.

Matthew Hutchinson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/tenth-minnesota-volunteer-infantry-regiment

The Lower Sioux Agency, or Redwood Agency, was built by the federal government in 1853 near the Redwood River in south-central Minnesota Territory. The Agency served as an administrative center for the Lower Sioux Reservation of Santee Dakota. It was also the site of key events related to the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

Matt Reicher, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/lower-sioux-agency

The Battle of Birch Coulee, fought between September 2 and 3, 1862, was the worst defeat the United States suffered and the Dakotas' most successful engagement during the US–Dakota War of 1862. Over thirty hours, approximately 200 Dakota warriors pinned down a Union force of 170 newly recruited US volunteers, militia, and civilians from the area, who were unable to move until Henry Sibley's main army arrived.

Eric Weber, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/battle-birch-coulee-september-2-3-1862

On September 23, 1862, United States troops, led by Colonel Henry Sibley, defeated Dakota warriors led by Ta Oyate Duta (His Red Nation, also known as Little Crow) at the Battle of Wood Lake. The battle marked the end of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

Iric Nathanson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/battle-wood-lake-september-23-1862