11 Beginnings of a Modern Era: The First World War and the Roaring Twenties

As the Progressives feverishly worked toward their most notable accomplishments during the 1910s, the nation’s attention was increasingly drawn beyond its borders. Americans first turned their gaze south toward Mexico which was convulsing in the throes of a drawn-out revolution, and then east toward Europe as it descended into the horrors of the First World War. While American troops were deployed to both places, they were sent in much larger numbers to Europe where they helped win what was hoped to be “the war to end all wars” in November of 1918. Post war demobilization was chaotic and made worse by race-based violence, the Red Scare, and the 1918 flu pandemic. In many ways, the following decade – the 1920s – ushered in modern America. Movies, cars, and radios drove a popular culture awkwardly constrained by a framework created by prohibition and a rural backlash to a rapidly changing world. While urban areas benefitted from a robust economy and dynamic changes ushered in by technological and cultural innovation, farmers struggled as demand for their crops fell and small-town populations pushed back against the rapid changes occurring in the country’s urban areas.

In 1910, Mexican revolutionaries overthrew the dictatorial government of Porfirio Diaz and the country descended into chaotic warfare that lasted a decade. American interventions in 1914 and again in 1916 accomplished little beyond souring relations between the two countries that had been strained since the Mexican American War of the 1840s. More importantly, the Mexican Revolution destabilized the country and led to a million Mexican deaths while encouraging perhaps as many as 1.5 million others to immigrate north to the United States during the first three decades of the 20th century. Many of these immigrants joined Mexican Americans already in the country and found migratory agricultural work. By the 1910s and 1920s, Minnesota agricultural companies began recruiting Mexican and Mexican-American labor – especially as sugar beet harvesters. While most returned south after the season, slowly families began to settle in small Minnesota towns like Albert Lea and Moorhead while others found their way to St Paul’s Westside where they created a vibrant Mexican American community in the capitol city.

In late June of 1914, a Serbian nationalist assassinated the heir to the Austria-Hungry throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife, in the Bosnian city of Sarajevo. The murders began a chain reaction which triggered an alliance system of bi-lateral mutual defense treaties that, until that point, had kept growing European militarism, nationalism, and imperialism in check. By early August, virtually all of Europe had descended into a war that pitted the Triple Entente (France, Great Britain, and Russia) against the Triple Alliance or Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire). While alarming, all of this seemed far away to Minnesotans and their fellow Americans, including President Wilson who declared American neutrality at the war’s outset.

As the war first stalemated and then dragged-on, it became increasingly difficult for the United States to remain neutral. Violations of free shipping that left American vessels subject to German submarine warfare, and a proposed alliance between Germany and Mexico uncovered by British intelligence added to growing economic concerns and pushed America toward war. In the spring of 1917, the United Sates entered the conflict in support of France and Great Britain. That fall, Bolshevik revolutionaries seized power in Russia, instilled a communist government, and withdrew from the war. The American entry more than made up for the Russian exit, and by November of 1918, the allied powers led by France, Great Britain, and the United States claimed a costly victory. The war had been devastating. New weapons, including: airplanes, submarines, tanks, artillery, machine guns, and poison gas transformed warfare and resulted in massive casualties on a scale the world had never seen. The loss of over 100,000 American troops, though devastating, paled in comparison to world-wide losses that exceeded 17 million.

In prosecuting the war, the American government felt it needed to actively campaign for support. Not only had Wilson urged Americans at the outset to remain “impartial in thought as well as in action,” but there had been no attack on the American homeland. More concerning was the 17 million Americans who had family ties to the Central Powers and the millions of Irish Americans who were wary of supporting Great Britain. For example, many midwestern states, including Minnesota, had large populations of German-Americans. To address these concerns, the federal government established the Office of War Information which used extensive and effective propaganda to convince Americans to support the war. In many measures the OWI was successful and Americans overwhelmingly came to support the war effort, but it also led to the violation of civil liberties and left a xenophobic legacy that ripened in the 1920s.

The country continued to face daunting challenges as it demobilized in the wake of the war. A flu pandemic killed 50 million people world-wide and in America sickened 20 million and killed 675,000. Inflation spiked, wages stagnated, and Americans faced shortages and saw their cost of living double. Approximately four million workers engaged in over 3,000 strikes in response. Race-based violence became commonplace as well when returning soldiers – White and Black – added tension to changing racial dynamics that had emerged after large numbers of African Americans moved to northern cities in search of war-time jobs. During the “Red Summer” of 1919 alone, 250 people died in 25 race riots.

Additionally, many Americans linked the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia with what they perceived as growing socialist radicalism in the American labor movement into a fear of a communist takeover of the American government. Tensions rose considerably when anarchist bombings led U.S. Attorney General Palmer to conduct raids that ended in widespread violations of civil liberties, the jailing of 5,000 Americans, and the deportation of 250 Russians. In northern Minnesota, the government crackdown on Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) activity was part of this larger Red Scare.

The realization that the “war to end all wars” had not seemed to make the world a better place, along with the chaos of the post-war years, convinced many Americans to shun activist-government whether it be in pursuit of domestic progressive reforms or international efforts to make the world safe for democracy. Wilson suffered a stroke during his unsuccessful attempts to convince the Congress to sign on to the Peace of Versailles that ended the war and established the League of Nations. In the election of 1920, and the two that followed, Americans elected Republican Presidents who promised a return to normalcy and an environment that would foster business growth and economic development.

We often remember the 1920s as the Jazz Age or the roaring twenties – a time that ushered in modernity. Movies, magazine, spectator sports, and radio broadcasts provided new opportunities for leisure activities that served to foster a national culture. The rise of advertising and the availability to purchase on credit allowed people wide-spread access to the latest consumer goods – none more important than the automobile that transformed where Americans lived, worked, and played. The Prohibition Era gave rise to an extra-legal night life and an opportunity organized crime could not resist. The period also provided an atmosphere where women, mostly those living in cities, began to redefine their role in society and challenge long-held norms. Prominent Minnesota authors took part in a literary movement later characterized as the Lost Generation, while African American musicians, artists, and authors led a cultural flowering centered in Harlem, New York that exposed the rest of the nation to many aspects of their culture.

Change was fast and at times unrelenting – especially for those living in rural areas and watching much of the transition from afar. An economy that was booming in the consumerism of the urban areas was struggling under the burden of low crop prices in rural areas. As the urban/rural divide expanded, a nativist backlash emerged that eyed immigrants with suspicion and resulted in restrictive immigration policies. A second and more mainstream Ku Klux Klan rose to prominence in the middle of the decade and used fear, intimidation, violence, and lynching as tools it aimed mostly at African Americans. Science and religion clashed in a cultural war that was highlighted in a small Tennessee town where a teacher was put on trial for teaching evolution in a high school.

Themes from 1920s America

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

In general, Minnesotans experienced the World War I and Prohibition eras much the same way other Americans did. At times, though, Minnesota played a more prominent role – as it did when its Commission of Public Safety took the nation’s quest to ensure patriotism to extremes, or when Charles Lindbergh became the first to fly across the Atlantic in 1927, or when Saint Paul infamously became a prized Prohibition-area gangster hangout.

Minnesota During the Great War

Section Highlights

- During World War I, 188,500 Minnesotans served in the military, 57,400 or who were deployed to Europe during the war.

- Over 3,600 Minnesotans died while serving their country during World War I.

- The Minnesota Commission of Public Safety (MCPS) dominated the home front during the war and strictly enforced patriot support of the war and violated the civil liberties of some Minnesotans.

- City leadership in New Ulm, a heavily German-American city, clashed with the MCPS during the war.

- The MCPS targeted the Nonpartisan League and the Industrial Workers of the World.

- The Minnesota Home Guard was the enforcement mechanism of the MCPS.

Although Minnesota supported neutrality early in the conflict, once the Congress had declared war in 1917, Minnesotans largely supported the war effort. By wars end, 118,500 Minnesotans had either been called up by the National Guard, enlisted, or been drafted into the armed services. Of that number, 57,400 were deployed to France. Most Minnesotan soldiers did not serve in isolated Minnesota units, but were dispersed across the military. The single exception to this rule was the 151st Field Artillery. First organized during the Civil War as the First Regiment of Heavy Artillery, the unit had been activated in 1916 to help defend the southern border in the wake of the Poncho Villa attack. Once the U.S. joined the European war, the unit was re-designated as the 151st, attached to the 42nd “Rainbow” Division, and sent to France. The “Gopher Gunners” served with distinction for 18 months, and endured a staggering 264 days of combat across six campaigns. Being the only Minnesota National Guard Unit to see action, it received a hero’s welcome home when it returned in May 1919. By war’s end, Minnesotans suffered 1,432 killed in battle and 2,175 additional casualties from sickness, disease and other causes. Many more returned physically injured, emotionally scarred, or both.[1]

Smaller numbers of Minnesota women also served in France – mostly as nurses, aid workers, and drivers. Most, however, served the war effort on the home front by filling vacated industrial jobs and assuming farm work as large numbers of men left for the war. In addition, women played a leading role in planting liberty gardens in support of food conservation efforts as the state and nation attempted to conserve food by advocating for meatless and wheatless meals. Women also, according to historian Kathryn Goetz, “joined, led, and donated their time and money to groups that provided soldiers with food, shelter, and supplies. They joined YWCA sewing and knitting circles to craft items for soldiers and civilians. They rolled bandages and collected funds for the Red Cross.”[2] The leaders of such efforts were often upper class and lived in urban areas where support for the war effort was generally higher.

Without question, Minnesota’s World War I home front was dominated by the activities of the Minnesota Commission of Public Safety (MCPS). On April 16, 1917, just over a week after the United States entered the war, the Minnesota legislature established a seven-member commission with broad powers to coordinate Minnesota’s war effort. Led by Governor Joseph A. A. Burnquist, the MCPS provided critical support for the state’s war effort, including establishing price controls, coordinating food distribution, and managing fuel conservation programs. These public-service activities, however, were soon overshadowed by the commission’s obsession with ensuring loyalty to the nation and its war effort. As historian Matt Reicher concisely stated, “ensuring clear-cut loyalty to America eventually overtook the MCPS’s other efforts.”[3] William Lass agreed, adding that the MCPS “became a virtual government in its own right, employing its own agents and constabulary. Arbitrarily assuming powers and responding vigorusly to the worse fears of superpatriots.”[4] Increasingly, the MCPS employed secret surveillance, public intimidation, and governmental actions to protect Minnesota from supposed subversion. In doing so, the commission focused its attention on three groups: Minnesotans with ethnic ties to the Central Powers, the Nonpartisan League, and the Industrial Workers of the World.

At the outbreak of the war, German was the single largest ethnic group in the state. Much of southern and western Minnesota was farmed by German immigrants or children of immigrants. In towns with the heaviest German-American concentrations, like New Ulm, German-language newspapers predominated and school lessons and church sermons were delivered in German. Given this reality, the MCPS feared, as did the Wilson Administration nationally, that these “hyphenated” Americans would not sufficiently support the war effort.

When rural Minnesota’s support for the war effort seemed to be lukewarm at best, the MCPS focused its energies to ensure compliance. More than anywhere else, New Ulm – a southern Minnesota town of 6,000 with a heavy German heritage – became a focal point for MCPS efforts. In late July, 1917, the city hosted an anti-draft rally at which prominent city leaders urged attendees to comply with a newly passed conscription law, but questioned the legality of sending New Ulm’s young men to fight in Europe. While praising the patriotism of the city, the speakers noted that their “people did not want to fight for Wall Street, England, or France.” They hoped to avoid sending New Ulm boys of German descent to fight Germans in Europe. While New Ulm and Brown County (of which New Ulm was the seat), ultimately complied with the draft law, the MCPS held investigative hearings in September and October. Governor Berquist removed the town mayor, Dr. Louis Fritsche and city attorney, Albert Pfaender from their offices for “promoting and participating in seditious public meetings.” Furthermore, Fritsche had his medical license revoked while Pfaender was expelled from the bar. The MCPS also pressured Martin Luther College to remove its President, Adolph Ackermann, for his role in the rally. Finally, Albert Steinhauser, an attorney turned newspaper editor was charged with sedition and arrested.[5]

The MCPS went on to encourage school boards to ban the use of German in public schools while Arch Bishop John Ireland put pressure on Catholic schools to do the same. Early in 1918, the commission began requiring non-citizens to register with the state and, among other things, explain why they had not yet become U.S. Citizens. The MCPS also encouraged private citizens to spy and report back on the supposed un-American activities of their neighbors. Some went beyond surveillance, as did a group of Minnesotans in the southwestern city of Luverne when they tarred and feathered a neighbor they suspected of disloyalty. They then drove him to South Dakota and promised to hang him if he returned to his farm.

In addition to potentially disloyal individuals, the MCPS also set its sights on radical labor organizations and political groups it deemed a menace to the war effort. As a result, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the Nonpartisan League (NPL) found themselves high on the list of MCPS priorities. Disgruntled miners and socialists had established the IWW in Chicago in 1905 and it soon became the most radical of labor unions – advocating, in the words of historian John Haynes, “the overthrow of capitalism through strikes, sabotage, and eventual revolution.”[6] By World War I, the IWW had reached the miners and lumberjacks in northern Minnesota and had orchestrated a Mesabi Range strike in the summer of 1916 and a work-stoppage against the Virginia and Rainy Lake Lumber Company later that year that spread to the entire lumber industry (see chapter 9). Connecting the IWW radicalism and socialist leanings to the Bolshevik Revolution and fear of international communism that came to be called the first Red Scare, the MSCP led a successful government campaign to dismantle the IWW.

Minnesota During World War I

Excerpt from Bring Warm Clothes

“Like many Minnesota soldiers, Longyear found himself overseas when the U.S. entered World War I. Back home, it was a time of super-patriotism and paranoia.”

Original Broadcast: 03/01/1996

Length: 7 minutes, 37 seconds.

In a similar fashion, the MCPS also set its sights on the Nonpartisan League. Established by North Dakota flax farmer Arthur Townley in 1915, the NPL had moved its headquarters to Saint Paul in 1917 just as the nation entered World War I. In many ways, the North Dakota NPL was the most-recent example of farmers organizing to advocate for their interests. Before expanding to Minnesota, the NPL had worked within the Republican Party to elect the North Dakota Governor and the majority of its legislature in 1916. Once in Saint Paul, the organization realized that since Minnesota was an urban and rural state, to be successful it had to unite farmers with urban and iron-range workers. Initially, it planned to continue to support NPL candidates within the Republican Party, but when their chosen gubernatorial candidate, Charles Lindbergh Sr., lost a close primary to sitting Republican Governor Burnquist, they ran David Evans as a third-party candidate. Although losing the election to the incumbent, Evans polled well above the Democratic challenger and the NPL emerged as a force in Minnesota politics that would soon develop into the Farmer Labor Party in the early 1920s.

Although the NLP had declared its support for the war effort, that its most high-profile candidate, Charles Lindbergh Sr., had opposed entering the war drew the attention of the MCPS. That the NLP advocated some socialistic policies, courted organized labor, and attracted German-American farmers as it sought to up-end the two-party system also brought suspicion of disloyalty. The MCPS was unable to outright ban the NPL, but it did work to disrupt its meetings and jailed Townley and other leaders. While campaigning in the Republican primary, Lindbergh was received warmly in some places but met with MCPS-inspired resistance in others – he was even shot at and hung in effigy. These heavy-handed tactics, while in-line with what was occurring elsewhere in the nation, pushed farmers toward more radical urban and iron-range workers into a political collaboration that helped give rise to the Farmer Labor Party.

Critical to the enforcement of MCPS policies and regulations, was the Minnesota Home Guard. Days after the MCPS was established, it created the Home Guard to replace the Minnesota National Guard that had been deployed to support the war effort. The Home Guard organized over 7,000 volunteers into 23 battalions and the following year added 2,500 more volunteers (along with their vehicles) into the Motor Corps that provided for the Guard’s transportation needs. The Guard and the Motor Corps provided needed services in support of the war effort, including: serving as honor guards and escorts, selling liberty bonds, harvesting crops, supporting Red Cross efforts, and providing disaster relief in the wake of a devastating tornado and forest fires that occurred late in the war.

The Home Guard also served as the enforcement arm of the Commission of Public Safety. It executed “slacker raids,” in search of draft dodgers – at one point, jailing 500 men from Saint Paul in a single operation. The MCPS also deployed the Guard to suppress efforts of organized labor. When transit workers in the Twin Cities went on strike in 1917, the Home Guard disbursed a crowd of thousands before clearing and securing a six-block section of downtown Saint Paul. Then and now, the Home Guard was controversial, as Peter DeCarlo summarized: “At times, the Home Guard helped bring stability to Minnesota during the World War I years. However, it was also a wedge that further divided opinion on issues like sedition and free speech, labor and business, loyalty and disloyalty, and race. Many people felt it was necessary; others thought it infringed on the rights of citizens.”[7]

A Difficult Transition: Minnesota at War’s End

Section Highlights

- On October 12, 1918 forest fires swept through Northeastern Minnesota killing 450 people and displacing thousands

- The 1918 Influenza Pandemic infected 500 million world wide, killing 50 million – including 675,000 Americans and 10,000 Minnesotans.

- In June of 1920, three African American young men were lynched in Duluth after being falsely accused of rape.

While the fall of 1918 brought a victorious end to the war, it also brought more devastation in the form of fire, sickness, and, several years later, race-driven violence to Minnesota.

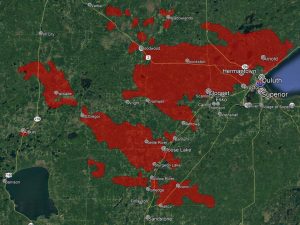

The fall of 1918 had been exceedingly dry, and sparks from locomotives coupled with high winds ignited a series of seven fires on October 12, 1918. The fires swept through a 1,500 square-mile section of Northeastern Minnesota, devastating the towns of Moose Lake, Cloquet, Hermantown and their surroundings. Within hours, 450 Minnesotans lost their lives and thousands more were displaced.

Just weeks before fires charred northeastern Minnesota, an even more devastating sickness reached the state. Misleadingly named the Spanish Flu, the virus that caused the pandemic originated in Kansas and was brought to Europe by American soldiers. Returning soldiers quickly spread the disease around the world and it arrived in Minnesota in September of 1918. The disease spread fast and killed quickly, causing health officials at the state and local levels to scramble to protect the public. Schools, public events, and places were closed and people encourage to avoid gatherings and wear masks. By the end, the pandemic infected 500 million people world-wide and killed over 50 million. In the United States, 50 million were sickened and approximately 675,000 succumbed to the disease, including 10,000 in Minnesota.[8]

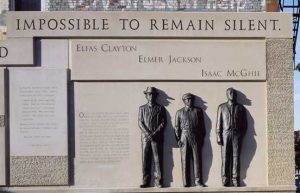

The third tragedy connected to the war’s end, a devastatingly brutal act of racially motivated violence, took place in the port city of Duluth in the summer of 1920. Falsely accused of rape, three African American men: Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, were lynched by a crowd numbering in the thousands. The three victims were working with a traveling circus and had been jailed after a teenaged girl accused them of raping her (a charge later disproven). After a sensational local newspaper story incited the city, a mob broke into the jail and lynched the three young men. While the details of the tragedy are specific to Duluth, the context in-which the murders took place are also connected to widespread racial tensions that gripped the nation at war’s end.

Employment opportunities created by the war accelerated the movement of African Americans from the rural South to northern cities. While Duluth, a growing industrial port city of 100,000 with a tiny African American population of less than 500, seemed far removed from the impact of this Great Migration, it wasn’t. US Steel operated a steel mill in Duluth and actively recruited African Americans to fill vacant positions throughout the war. Similar to experiences in larger cities, the growing Black population in Duluth faced discrimination and restrictions in where people could eat, shop, and live. As soldiers returned from the war, racial tensions intensified across the north and, during 1919, violence broke out in 25 cities. The following summer, violence reached Duluth.

In the wake of the lynchings, Duluth’s Black population plummeted even as the city itself continued to grow. Those who chose to stay, established a branch of the NAACP and worked with other Minnesotans under the leadership of St Paul’s Nellie Stone Johnson to enact anti-lynching legislation. More recently, the city of Duluth has attempted to come to terms with the tragedy by creating a memorial and developing school curriculum around the events that had been previously obscured by city and state histories.

Minnesota’s Roaring Twenties

Section Highlights

- Prohibition lasted from 1920 to 1933 providing an opportunity for Kid Cann in Minneapolis to emerge as a crime boss, and Saint Paul to develop into a haven for criminals.

- While many sectors of the state enjoyed favorable economic conditions, Minnesota farmers struggled as prices fell after World War I ended.

- F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sinclair Lewis were Minnesota-born writers of the Lost Generation.

- Automobiles became widely available and emerged a life-changing mode of transportation.

- Northwest Airlines emerged in the early 1920s and Charles Lindbergh Jr., became the first person to fly a plane across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927.

- Electricity and indoor plumbing was widely available in cities and town, but not in rural areas.

- Wilbur Foshay, who made a fortune in public utilities and built the Foshay Tower in Minneapolis, lost everything after the stock market crashed in 1929 and shortly after went to prison for misleading his investors in a Ponzi scheme.

During the 1920s, Minnesotans and their fellow Americans pushed boundaries in technology, travel, and culture as the state and nation emerged into the modern era. Like the rest of the nation, Minnesota became more urban than it was rural – meaning more people came to live in urban places of 2,500 people or more than those living on farms, or in small towns, or in rural villages. Minnesota’s developing urban culture of its largest cities – Minneapolis, Saint Paul, and Duluth – led the state’s transition into the modern era driven by mass media (advertising, movies, radio), automobiles, electricity, modern conveniences, buying on credit, and an upturning of age-old cultural norms that had dictated women’s accepted role in society. Prohibition which had gone into effect in January of 1920 and unintentionally created a vibrant night life driven by speakeasies and controlled by organized crime syndicates made this emergence into the modern more traumatic. But even as urban Minnesotans charged ahead into the modern, people living in rural areas of the state (just under half of the population), clung more closely to the familiar, and eyed changes emerging from the cities with skepticism.

Prohibition created a cultural backdrop to life in Minnesota’s largest cities. A vibrant night-life gave some women, often called flappers, the opportunity to push long-accepted norms. They wore new fashions, frequented speakeasies with male counterparts, danced, smoked and became more independent. The national ban on the manufacture, transportation and sale of alcohol also created an opportunity for organized crime to prosper. In Minneapolis, Prohibition assisted the up-and-coming criminal Isadore Blumenfeld, known as Kid Cann, in his quest to become a crime boss. He went on to a long career in bootlegging, racketeering, and a variety of other illegal activities. Accused of several murders and a host of other crimes, Cann for the most part avoided long prison sentences and died rich in 1981.

In Saint Paul, the era propelled an already corrupt system in which the police department regulated and controlled criminal activity in the city. Prior to Prohibition’s enactment, Saint Paul Police Chief, John O’Connor, had created a corrupt system in-which criminals paid bribes to be left-alone and even protected by the police when in Saint Paul. As Prohibition became the law of the land, O’Connor left office, but his lay-over system did not leave the city. By the early 1930s, Saint Paul had a well-earned reputation as a gangster’s haven. Perhaps Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, one of the city’s most well-known criminals, put it best: “Every criminal of any importance in the 1930s made his home at one time or another in St Paul. If you were looking for a guy you hadn’t seen for a few months, you usually thought of two places – prison or St Paul. If he wasn’t locked up in one, he was probably hanging out in the other.”[9] The Ma Barker Gang, Machine Gun Kelly, and John Dillinger are just a few of the gangsters who frequented St Paul as a result of its reputation. When the nation repealed Prohibition in 1933, St Paul criminals became more violent and turned to high-profile kidnapping and ransom schemes that eventually led to an FBI crackdown.

Saint Paul: Gangster’s Haven

This week’s lecture takes a closer look at Saint Paul during the 1920s and early 1930s.

The economic conditions of urban versus rural Minnesota differed during the 1920s. While the urban economy boomed – spurred on by the availability of new modern devices, advertisers, and available credit – rural Minnesota farmers struggled with a stagnating produce market brought on by the end of the war. Prices for farm commodities peaked in 1919 but as Europe recovered from the war, the prices sank rapidly. To make matters worse, many farmers had recently acquired debt to purchase land and equipment when wartime demand drove up prices. While other sectors of the state and nation enjoyed a robust economy throughout the 1920s, for Minnesota farmers the Great Depression started early. Between 1926 and 1932 Minnesota farmers lost 1,442 farms accounting for over 258,500 acres to foreclosure.[10]

Transportation by automobile and airplane also accelerated during the first two decades of the twentieth century. During the 1910s, Minnesota’s “Good Roads” movement, first initiated by bicyclists, began improving roads for the more than 42,000 automobiles that were operating in the state by 1913. In 1921, the state created the Minnesota Department of Highways to further the work of creating, improving, and maintaining the state’s roads. In 1914, a mineworker turned auto-dealer, Carl Wickman, began a bus service for iron miners in Hibbing. Three years later, the service incorporated into the Mesabi Transportation Company which became the Greyhound Corporation in 1930.

It was not long after the Wright brother’s historic 1903 flight in North Carolina that commercial air travel began to develop. In Minnesota, a Saint Paul businessman backed by out-of-state investors established Northwest Airlines to transport mail and passengers from the Twin Cities to Chicago. The venture became one of the most successful airline companies over its 80-year history before being acquired by Delta Airlines in 2008. Perhaps another Minnesotan, Charles Lindbergh, Jr., did more for the development of aviation than any other when the Little Falls native became the first to fly an airplane non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927. In the wake of his historic flight, he used his celebrity to advance aviation and worked with his wife, Ann Murrow – also a pilot, to map airline routes across the country.

It was not long after the Wright brother’s historic 1903 flight in North Carolina that commercial air travel began to develop. In Minnesota, a Saint Paul businessman backed by out-of-state investors established Northwest Airlines to transport mail and passengers from the Twin Cities to Chicago. The venture became one of the most successful airline companies over its 80-year history before being acquired by Delta Airlines in 2008. Perhaps another Minnesotan, Charles Lindbergh, Jr., did more for the development of aviation than any other when the Little Falls native became the first to fly an airplane non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927. In the wake of his historic flight, he used his celebrity to advance aviation and worked with his wife, Ann Murrow – also a pilot, to map airline routes across the country.

Minnesota’s Lost Generation

The difference between life in larger urban areas and small-town Minnesota can also be seen in the work of two of Minnesota’s most renowned authors of the era: F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sinclair Lewis. Both were prominent members of a group of American authors known as the Lost Generation, and both relied heavily on their childhood experiences – in Saint Paul for Fitzgerald and in Sauk Center for Lewis. Fitzgerald is perhaps best known for his 1925 Great Gatsby novel that celebrated Long Island’s urban Jazz-Age culture. The book’s main character, Nick Carraway, remembers his St Paul home fondly as much smaller and more stable than his Long Island surroundings. Like many authors of the era, Fitzgerald wrote short stories for magazines – many of which he set in his Saint Paul childhood. A collection of his St. Paul-based stories was compiled and published in the 2004 The St. Paul Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Throughout his career, Fitzgerald became closely associated with a city-centered Jazz Age culture his writing highlighted.

By contrast, Sinclair Lewis’s breakout 1920 novel, Main Street, is set in the fictitious small town of Gopher Prairie, MN (a little disguised replica of Lewis’s Sauk Center boyhood home that had a population of 2,700 in 1920). The book’s heroine, Carol Kennicott, leaves St. Paul after marrying a doctor from Gopher Prairie. The novel highlights the differences between life in St Paul versus the much smaller Gopher Prairie. Lewis is cynical of his fictionalized hometown and depicts a Gopher Prairie population content in their lives and weary of changes occurring in larger cities. Taken together, the works of Fitzgerald and Lewis highlight the different life experiences between people living in large metropolitan areas and those living in small-town Minnesota.

During the 1920s, electricity and in-door plumbing where widely available to people living in larger cities and smaller towns. These two conveniences made lives much easier for those who had them. But not everyone living in the state’s largest and most technologically advanced cities had access to these life-changing conveniences. The shacks and shanties of immigrant communities in Saint Paul’s Westside Flats and Swede Hollow along with Minneapolis’s Bohemian Flats lacked both electricity and plumbing – not only making life more difficult, but also increasing the risks to public health. Likewise, Minnesotans living on rural farms largely went without these two conveniences. Of the 185,255 farms in 1930, only 23,342 had indoor lighting (and the vast majority of those were gas lights, not electric). Because it was not cost-effective for power companies to deliver electricity to sparsely populated rural areas, as late as 1934 less than 7% of Minnesota farms had central-station electrical service.[11] By the middle of the 1930s, the Federal Rural Electrification Administration (REA) began working to bring electricity to Minnesota farms, but the work was slow and some went without until well into the 1950s.

Prior to the Federal Government’s creation of the REA, demand for electricity in the growing cities and from rural families anxious to take advantage of electric lights and in-door plumbing provided a lucrative business opportunity for forward-looking entrepreneurs. One such visionary was Wilbur Foshay, who arrived in Minneapolis around 1913 and began building a national public utilities empire. Many of the companies Foshay acquired worked to provide power to rural residents, including some in Minnesota. As his holdings and wealth grew, Foshay began constructing a headquarters in downtown Minneapolis to not only house his business offices, but also to display his self-made success. Integrated into a two-story building Foshay had renovated into a pedestal, the 32-story Foshay Tower rose to 447 feet and was built to resemble the Washington Monument. The structure design made use of the latest technological advancements and was constructed from fabricated steel and reinforced concrete. Not only did the tower become the city’s first sky scraper, but it was the tallest building between Chicago and the West Coast. It opened with a three-day celebration held from August 30th to September 1st, 1929 that included fireworks displays, a march written by John Philip Sousa, and special guest dignitaries from around the country – brought to Minneapolis at the company’s expense.

Sadly, many of the construction and celebration expenses went unpaid and Foshay’s company only occupied the building for two months. As the building opened, the W.B. Foshay Company was having difficulties meeting its financial obligations and two months later, when the stock market crashed at the end of October, 1929, Foshay lost everything. His company immediately went bankrupt, and his creditors went unpaid. After leaving the city for Colorado, Foshay got word that the Federal Government was investigating him for mail fraud. In what today is known as a Ponzi scheme, Foshay had defrauded his investors by misleading them about his company’s value and paying dividends from additional share sales and not company profits. His misdeeds resulted in a 15-year sentence he began serving in Leavenworth Prison in the Spring of 1934. Three years later, President Roosevelt commuted his sentence and later President Truman issued him a pardon.

The Foshay Tower

- The Foshay Tower, 1929

- Today the Foshay Tower remains a Minneapolis landmark

- Wilbur Foshay, 1929

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

Foshay’s meteoric rise and devastating fall was in a way emblematic of 1920s America. He embraced the modern and appeared to have made a fortune providing electric power to those who craved the decade’s comforts. He used fabricated steel – the innovation allowing 1920s cities to grow up rather than out – to create a symbol of his wealth. But he had employed unsound and deceptive business practices to grow his company on pretend value – an underlying problem that infected the economy in general and led to its demise in the fall of 1929.

Conclusion

Minnesota’s contributions to the war effort during the First World War were significant despite the misgivings of many of its German-American inhabitants. As the state’s young men fought overseas, the Commission of Public Safety worked to enforce patriotism sometimes at the expense of civil rights. At war’s end, the state struggled with a devastating pandemic, a distressing fire, a Red Scare, and racial violence that ended with the murder of three young African American men. The 1920s brought the state and the nation into the modern era city-first, with rural populations cautiously following at a distance. Finally, the rise-and-fall story of Wilbur Foshay provided a microcosm of the recklessness of the roaring twenties and foreshadowed significant problems on the horizon.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

“Duluth Lynchings: Resources Relating to the Tragic Events of June 15, 1920.” Minnesota Historical Society. https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/ (accessed May 24, 2022).

Hampl, Patricia and Dave Page (eds.) The Saint Paul Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald. St. Paul, MN: Borealis Books, 2004.

Maccabee, Paul. John Dillinger Slept Here: A Crooks’ Tour of Crime and Corruption in St. Paul, 1920-1936. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1995.

Nathanson, Iric. World War I Minnesota. Chareslton, SC: The History Press, 2016.

“Wilbur B. Foshay: The Man & His Tower, Part I” , 08 Mar 2011, Ampers. https://ampers.org/mn-art-culture-history/wilbur-b-foshay-the-man-his-tower-part-i/. (accessed May 24, 2022).

“Wilbur B. Foshay: The Man & His Tower, Part II” , 08 Mar 2011, Ampers https://ampers.org/mn-art-culture-history/wilbur-b-foshay-the-man-his-tower-part-ii/. (accessed May 24, 2022).

- Johnson, Jack K. "151st Field Artillery Regiment." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/151st-field-artillery-regiment (accessed May 3, 2022). ↵

- Goetz, Kathryn. "Women on the World War I Home Front." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/women-world-war-i-home-front (accessed May 3, 2022). ↵

- Reicher, Matt. "Minnesota Commission of Public Safety." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/minnesota-commission-public-safety (accessed May 3, 2022). ↵

- William Lass, Minnesota: A History, Second Edition. (New York: Norton, 1998), 219. ↵

- Nelson, Paul. "New Ulm Military Draft Meeting, 1917." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/event/new-ulm-military-draft-meeting-1917 (accessed May 9, 2022). ↵

- John E. Haynes, “Revolt of the Timber Beasts” - IWW Lumber Strike in Minnesota.” Minnesota History, Spring 1971, 163-174. ↵

- DeCarlo, Peter. "Minnesota Home Guard." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/minnesota-home-guard (accessed May 9, 2022). ↵

- Laine, Mary. "Influenza Epidemic in Minnesota, 1918." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/event/influenza-epidemic-minnesota-1918 (accessed May 6, 2022). ↵

- Paul Maccabee, John Dillinger Slept Here: A Crooks’ Tour of Crime and Corruption in St. Paul, 1920-1936. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1995. ↵

- Cameron, Linda A. "Agricultural Depression, 1920–1934." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/agricultural-depression-1920-1934 (accessed May 23, 2022). ↵

- Cameron, Linda A. "Agricultural Depression, 1920–1934." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/agricultural-depression-1920-1934 (accessed May 23, 2022). ↵

The growth of cities and industry in the late nineteenth century brought sweeping changes to American society. Minneapolis and Saint Paul grew rapidly. Urban labor provided new opportunities for Minnesotans as well as new challenges. Business practices and labor rights became topics of heated debate. The Progressive movement spread amid growing concerns about the place of ordinary Americans in the new urban landscape.

Thomas Backerud, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/progressive-era-minnesota-1899-1920

From the 1850s to the 1960s, St. Paul’s West Side Flats was a poor, immigrant neighborhood—frequently flooded but home to a diverse group of Irish, Jewish, and Mexican workers and their families. In the early 1960s all residents were moved out to make way for an industrial park.

Paul Nelson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/west-side-flats-st-paul

“I had a little bird, its name was Enza. I opened the window, and In-Flu-Enza!” Children innocently sang this rhyme while playing and skipping rope during the 1918 influenza pandemic, which caused an estimated fifty million deaths worldwide. 675,000 of these were in the United States; over 10,000 were in Minnesota.

Mary Laine, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/influenza-epidemic-minnesota-1918

In December of 1916, mill workers at the Virginia and Rainy Lake Lumber Company went on strike, and lumberjacks soon followed. The company police and local government tried to crush the strike by running the lumberjacks out of town, but when the strike was called off in February, the company had granted most of the workers’ demands.

Anja Witek, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/iww-lumber-strike-1916-1917

Writers of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution took a little more than one hundred words to prohibit the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages. It fell to Minnesota Congressman Andrew Volstead to write the regulations and rules for enforcement. The twelve-thousand-word Volstead Act remained in effect for thirteen years, from 1920 until Prohibition was repealed in December 1933.

Rae Katherine Eighmey, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/national-prohibition-act-volstead-act

A group of American writers who came of age during World War I and established their literary reputations in the 1920s. The term is also used more generally to refer to the post-World War I generation.

Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lost-Generation

The 151st Field Artillery is one of the oldest, most decorated units in the Minnesota National Guard. Its performance in combat during World War I as part of the Forty-second “Rainbow” Division, and during World War II with the Thirty-fourth “Red Bull” Division, drew high praise from senior Army commanders and remains a source of pride to the soldiers in its ranks.

Jack Johnson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/151st-field-artillery-regiment

On April 12, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson called upon Americans on the home front to help fight what would become known as World War I. In response, many Minnesotans turned to backyard gardening to increase their food supply. Homegrown vegetables filled pantries and stomachs and allowed “citizen soldiers” to conserve wheat, meat, sugar, and fats that were essential for U.S. troops and their European allies.

Rae Katherine Eighmey, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/liberty-gardens-1917-1919

The Minnesota Commission of Public Safety (MCPS) was a watchdog group created in 1917. Its purpose was to mobilize the state's resources during World War I. During a two-year reign its members enacted policies intended to protect the state from foreign threats. They also used broad political power and a sweeping definition of disloyalty to thwart those who disagreed with them.

Matt Reicher, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/minnesota-commission-public-safety

Exploited by powerful corporate and political interests in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Midwestern farmers banded together in the early twentieth century to fight for their political and economic rights. Farmers formed the Nonpartisan League (NPL) and wrote a significant chapter of Minnesota's progressive-era history.

Peter DeCarlo, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/nonpartisan-league

The World War I draft rally held in New Ulm on July 25, 1917, was an exciting event; it featured a parade, music, a giant crowd, and compelling speakers. The speakers urged compliance with law, but challenged the justice of the war and the government’s authority to send draftees into combat overseas. In the end, people obeyed the draft law, while the state punished dissent. Three of the speakers lost their jobs; the fourth was charged with criminal sedition.

Paul Nelson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/new-ulm-military-draft-meeting-1917

Born in County Kilkenny, Ireland, in 1838, John Ireland came to St. Paul with his parents in 1852. He was ordained a Catholic priest in 1861, served briefly as chaplain for the Fifth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment in the Civil War, and was appointed bishop in 1875. By the time he was appointed archbishop of St. Paul in 1888, he was one of the city's most prominent citizens, and he was responsible for recruiting Irish immigrants to settle in communities throughout Minnesota, including Clontarf, Adrian, Graceville, and Ghent.

Kate Roberts, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/ireland-john-1838-1918

Charles August (C. A.) Lindbergh, father of the aviator Charles Augustus Lindbergh, was a Little Falls lawyer who represented Minnesota’s Sixth District in the United States Congress for five terms. He was a leader of the progressive wing of the Republican Party and opposed the United States’ entry into World War I. As the nominee of the Nonpartisan League, he waged an unsuccessful campaign to unseat Governor Joseph Burnquist in the bitterly fought 1918 gubernatorial Republican primary.

Greg Gaut, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/lindbergh-charles-sr-1859-1924

Minnesota's Farmer-Labor Party (FLP) represents one of the most successful progressive third-party coalitions in American history. From its roots in 1917 through the early 1940s, the FLP elected hundreds of candidates to state and national office and created a powerful movement based on the needs of struggling workers and farmers.

Tom O'Connell, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/minnesota-farmer-labor-party-1924-1944

When the Minnesota National Guard was federalized in the spring of 1917, the state was left without any military organization. To defend the state’s resources, the Minnesota Commission of Public Safety (MCPS) created the Minnesota Home Guard. The Home Guard existed for the duration of World War I, and units performed both civilian and military duties.

Peter DeCarlo, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/minnesota-home-guard

The Minnesota Motor Corps was the first militarized organization of its kind in the United States. Made up of volunteers and their vehicles, the corps existed for the duration of World War I. It provided disaster relief, transported troops, and aided police. The Motor Corps’ services proved crucial, but many viewed it as a state-sponsored police force that infringed on the rights of citizens.

Peter DeCarlo, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/minnesota-motor-corps

The worst natural disaster in Minnesota history—over 450 dead, fifteen hundred square miles consumed, towns and villages burned flat—unfolded at a frightening pace, lasting less than fifteen hours from beginning to end. The fire began around midday on Saturday, October 12, 1918. By 3:00 a.m. on Sunday, all was over but the smoldering, the suffering, and the recovery.

Paul Nelson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/cloquet-duluth-and-moose-lake-fires-1918

Lynching is widely believed to be something that happened only in the South. But on June 15, 1920, three African Americans, Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, were lynched in Duluth, Minnesota.

Tina Burnside, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/duluth-lynchings

In the years leading up to and immediately following World War I, African Americans in St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Duluth established separate chapters of the recently formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Dave Kenney, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/origins-naacp-minnesota-1912-1920

Nellie Stone Johnson was an African American union and civil rights leader whose career spanned the class-conscious politics of the 1930s and the liberal reforms of the Minnesota DFL Party. She believed unions and education were paths to economic security for African Americans, including women. Her self-reliant personality and pragmatic politics sustained her long and active life.

Tom Beer, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/johnson-nellie-stone-1905-2002

In the annals of Minneapolis crime one man occupies the place held by Al Capone in Chicago and Meyer Lansky in New York and Miami: Isadore Blumenfeld, also known as Kid Cann. He was a lifelong criminal who made fortunes in liquor, gambling, labor racketeering (all protected through political corruption), and real estate. Only late in life did he serve more than a year in prison. He retired in Florida and died rich.

Paul Nelson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/blumenfeld-isadore-kid-cann-1900-1981

The O'Connor layover agreement was instituted by John O'Connor shortly after his promotion from St. Paul detective to chief of police on June 11, 1900. It allowed criminals to stay in the city under three conditions: that they checked in with police upon their arrival; agreed to pay bribes to city officials; and committed no major crimes in the city of St. Paul. This arrangement lasted for almost forty years, ending when rampant corruption forced crusading local citizens and the federal government to step in.

Matt Reicher, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/oconnor-layover-agreement

A few months before aviator Charles Lindbergh made his record-breaking transatlantic flight, Northwest Airways, Inc. began carrying airmail between the Twin Cities and Chicago. As Northwest Airlines, Inc., the company became a major international carrier before financial troubles forced its merger with Delta Air Lines, Inc. in 2008.

Linda Cameron, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/northwest-airlines

Charles A. Lindbergh, a native of Little Falls, became a world-famous aviator after completing the first nonstop, solo transatlantic flight in May 1927. Although his flying feats made him an American cultural hero in the 1920s, his links to Nazism, support for eugenics, and publicly unacknowledged children in Germany tarnished his legacy in the decades that followed.

Melissa Peterson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/lindbergh-charles-1902-1974

Author F. Scott Fitzgerald is a cultural icon of the Roaring Twenties and the Jazz Age. His work, although largely under-appreciated during his lifetime, reflects the thoughts and feelings of his generation.

Thomas Backerud, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/fitzgerald-f-scott-1896-1940

Sauk Centre’s Sinclair Lewis, short story writer, novelist, and playwright, was the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Patrick Coleman, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/lewis-harry-sinclair-1885-1951

Nestled into a small valley between the mansions of Dayton's Bluff and St. Paul proper, Swede Hollow was a bustling community tucked away from the prying eyes of the city above. It lacked more than it offered; houses had no plumbing, electricity, or yards, and there were no roads or businesses. In spite of this, it provided a home to the poorest immigrants in St. Paul for nearly a century.

Matt Reicher, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/swede-hollow

On May 11, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 7037 to create the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), a New Deal public relief program. The program provided $1 million for federal loans to bring electric service to rural areas. It revolutionized life in rural Minnesota and across the country.

Linda Cameron, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/rural-electrification-administration-minnesota

In 1932, singer Bing Crosby had a major hit with his recording of E. Y. Harburg and Jay Gorney's song "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?" Its lyrics could have been the story of Wilbur B. Foshay: "Once I built a tower up to the sun/ brick and rivet and lime/ Once I built a tower, now it's done/ Brother, can you spare a dime?" Foshay built a fortune, built a tower in Minneapolis—and then lost it all in the stock market crash of 1929.

Britt Aamodt, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/foshay-wilbur-1881-1957

Since 1929, the Foshay Tower has been a vital part of the Minneapolis skyline. When it was built, the thirty-two-story tower was the tallest building between Chicago and the West Coast. In the 1970s and 1980s, much taller skyscrapers were built, but the attractive Foshay Tower remained a crowning glory of Minnesota architecture.

Britt Aamodt, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/structure/foshay-tower