6 The United States of America: Expanding the Western Frontier

The 1783 Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War and created the United States of America with its western boundary at the Mississippi River. As a result, portions of the future state of Minnesota east of the Mississippi fell within the claims of the new nation, but Spain retained title to most of what would become Minnesota. In the early 1800s, Spain transferred its land claims west of the Mississippi to France before the United States acquired the territory through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Finally, in 1842, the United States and Great Britain agreed on the previously disputed northern border west of Lake Superior. This agreement made the last remaining portions of the future state of Minnesota part of the territorial claims of the United States. European maps claiming who owned what had not mattered much in Minnesota because, in reality, the Dakota and Ojibwe controlled the region. As the new United States gained momentum, however, American maps did start to matter. Unlike the Europeans who entered Minnesota primarily for trade, the Americans came to Minnesota looking for much more – they wanted to acquire the land and did so at a startling speed.

The American acquisition and settlement of Minnesota were part of a larger national story driven by the idea of Manifest Destiny – a belief that God had destined the new nation to expand across North America. By the 1840s, just as Minnesota was filling up with European immigrants and Euro-Americans from the Northeast, the country made good on its expansionist aspirations. It enlarged its territorial holdings by some 70% by acquiring land in the Pacific Northwest through diplomacy and in the Southwest through war. From one perspective, Manifest Destiny brought representative government, religious freedom, economic opportunity, and large degrees of personal freedom. These benefits, however, were mostly reserved for Euro-Americans and excluded nearly all others. From the perspective of those seemingly excluded from an equal place in the expanding nation – Mexicans, enslaved African Americans, and indigenous Americans (including the Dakota and Ojibwe in Minnesota) – Manifest Destiny brought a new and, in many ways, distressing reality.

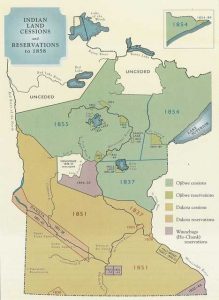

The new nation’s first attempt at creating a presence in Minnesota came in 1805 when Lieutenant Zebulon Pike arrived in search of a suitable location for a military post. In negotiations with Dakota leadership, Pike purchased two tracks of land – one at the confluence of the St Croix and Mississippi Rivers and the other at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers – and began a process of dubious treaty making that transferred Minnesota lands from the Dakota and Ojibwe to the United States. During the 1820s, the United States military constructed Fort Snelling in what one day would become the metropolitan area of Minneapolis and Saint Paul. 1830s treaties acquired land between the Mississippi and the St Croix. Additional treaties in the 1850s transferred most of the rest of Minnesota from the Dakota and Ojibwe people to the United States. While indigenous people were pushed onto reservations, Euro-American populations skyrocketed. In 1849, Minnesota became a territory, and in 1858, it reached statehood.

Fort Snelling at Bdote

Section Highlights

- The U.S. military constructed Fort Snelling at the meeting point of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, a place the Dakota call Bdote, in the 1820s.

- Fort Snelling established a U.S. presence in the region, dissuaded British interference in the area, policed the fur trade, and attempted to keep the peace between the Dakota and Ojibwe.

- The U.S. Government established the St. Peters Indian Agency near the fort to administer federal Indian policy.

- Despite being illegal, slavery existed in Minnesota and was centered at the fort.

Due to a variety of domestic and international circumstances, including the War of 1812, it took the United States 14 years to follow up on Pike’s treaty. Then, in the summer of 1819, Major Thomas Forsyth arrived at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers, a place the Dakota called Bdote, with payment for the 14-year-old treaty that ceded the area to the United States. Although Pike had estimated the value of the land at $200,000, Forsyth delivered just $2,000 in goods to Dakota leaders as payment for the land. By late summer, just over 200 U.S. soldiers under Lieutenant Colonel Henry Leavenworth were busy erecting quarters and preparing to build a military outpost. Pike had indeed chosen a strategic location, according to the secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, “the post at the mouth of the St. Peter’s is at the head of navigation on the Mississippi, and in addition to its commanding positions in relation to the Indians, it possesses great advantages, either to protect our trade, or prevent that of foreigners.”[1] Although the fur trade would soon enter a downward spiral, it remained top of mind when choosing the location for the military’s westernmost post.

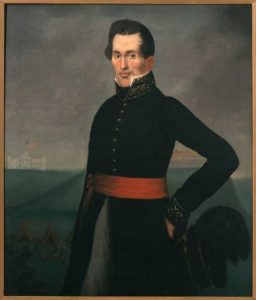

Work on the fort lagged, and the soldiers endured a difficult first winter that left over 30 of them dead by spring. Late the following summer, the War Department sent Colonel Josiah Snelling to replace Leavenworth. Under Snelling’s leadership, construction of a diamond-shaped stone structure, initially called Fort St. Anthony, began in September of 1820. The fort was completed in 1823 and renamed in honor of Colonel Snelling two years later. In addition to dissuading further British interference on the frontier and policing the fur trade, soldiers at the fort were charged with keeping Euro-Americans off Dakota and Ojibwe lands and attempting to resolve disputes between the two that might threaten the fur trade.

St. Peters Indian Agency

As the military constructed Fort Snelling, the federal government also established the St. Peters Indian Agency adjacent to the fort. From 1820 to 1839, Lawrence Taliaferro (pronounced TAHL-ih-ver) served as the government’s Indian Agent in charge of enforcing fur trade regulations, negotiating treaties, and resolving disputes between the Dakota and Ojibwe. In an agency rife with corrupted and incompetent agents, Taliaferro proved the exception – he was honest and consistently advocated for what he believed were the best interests of the Dakota and Ojibwe. Unfortunately, what Taliaferro believed was best for the Dakota and Ojibwe was driven by his worldview that saw indigenous people as inferior to Euro-Americans. Taliaferro was a slave-holding Virginian who believed in a strict racial hierarchy. According to historian Mary Wingerd, Taliaferro “never doubted that his natural superiority as a white man and gentleman granted him the duty and the right to look out for their interests as he determined was best.”[2] This outlook led him to push assimilation policies, advocated by the federal government, that attempted to remake the Dakota and Ojibwe in the image of Euro-American farmers.

Taliaferro’s vision of a neatly structured hierarchical society was still elusive in 1820s Minnesota. The American presence at Bdote was growing, but still in its infancy. It was dwarfed by a relatively egalitarian society dominated by the Dakota and made diverse by the presence of the Ojibwe, French Canadian fur traders, Swiss and Scottish refugees from the failed Selkirk Colony, and countless people of mixed ethnicity. Historian Peter Decarlo summarized the atmosphere, stating: “the 1830s was the most culturally diverse period in the early history of Fort Snelling and Bdote. The Dakota were the region’s most powerful residents, the fur trade was of great economic importance, and the small European American community was relatively isolated from the rest of the United States. Several fur traders, military officers married Dakota Women… establishing important kinship ties.”[3]

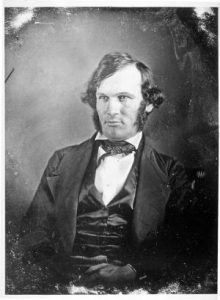

Perhaps Taliaferro’s biggest challenge was policing the fur trade, and his attempts to do so brought him into near constant conflict with traders. By the 1820s, the Fort Snelling area had become the hub of the fur trade in Minnesota, and the American Fur Company had established its headquarters across the river from the fort in a community called Mendota (an alternative pronunciation of Bdote – the Dakota name). In 1834, the 24-year-old Henry Hastings Sibley arrived to take charge of the company’s operations. Sibley ended up making a career in Minnesota – he came to play an important role in the early political and military history of the soon-to-be territory and state of Minnesota.

Slavery at Fort Snelling

Despite being made illegal by the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 and later the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Slavery existed in Minnesota and was centered at Fort Snelling. Regardless of federal laws, throughout Minnesota’s pre-territorial period and while it was a territory from 1849 to 1858, army officers, government employees, vacationing visitors, and new residents all brought enslaved people to Minnesota. Although the region’s largest single slaveholder was Indian Agent Lawrence Taliaferro, the largest group of slave holders were US Army officers, including Colonel Snelling, who brought enslaved people to serve as personal servants while deployed to the fort. During the 1820s and 1830s, anywhere between 15 and over 30 enslaved people were forced to reside at the fort. When future President Lieutenant Colonel Zachary Taylor brought the First US Infantry to the fort in 1828, 33 out of his 38 officers enslaved people at some point during their Fort Snelling deployment.

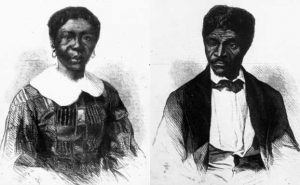

While most of the personal details of those enslaved at the fort are lost to history, several of those enslaved are well known even today. Among the most prominent were Dred Scott and Harriet Robinson. Lawrence Taliaferro brought Harriet Robison from Virginia to the fort as one of his slaves in 1835. She married Dred Scott, who had been brought to the fort by an army surgeon. The two were married in a ceremony presided over by Taliaferro sometime in 1836 or 1837. When forced south by circumstances beyond their control, Dred and Harriet sued for their freedom on the basis that they were illegally enslaved in territory that was supposed to be closed to slavery. While other enslaved people in Minnesota had successfully won their freedom in similar suits, Dred and Harriet’s effort became bogged down in continual and escalating litigation. The suit, first brought in 1846, bounced around various courts until it found its way to the US Supreme Court in 1857. The high court ruled that Dred and Harriet, being African American, did not have access to the courts and dismissed their case. Also importantly, the ruling invalidated the Missouri Compromise’s prohibition of slavery (or any prohibition of slavery anywhere, actually). While the case’s notoriety eventually led to the Scotts and their two daughters being sold and then freed, the case itself further divided the country as it stumbled toward civil war.

Slavery in Minnesota

In Scholar Module 3 we will look at the stories of three people enslaved in Minnesota.

Pig’s Eye

Section Highlights

- 1837 treaties opened land up to Euro-American settlement between the Saint Croix and Mississippi Rivers south of Mille Lacs.

- In 1838, over 150 families who had been squatting on land near the fort moved four miles down the river to what was briefly known as Pig’s Eye but soon became Saint Paul.

- Saint Paul grew rapidly and was designated the territorial capital city in 1849.

- Other cities, including Marine on St Croix, Stillwater, and Saint Anthony, developed along the rivers in the territory acquired in the 1837 treaties.

By 1823, the first steamboats had arrived in the vicinity of the fort, and the military outpost, along with the trading center across the river at Mendota, were becoming busier places. In 1837, two treaties transferred land south of Mille Lacs and between the Mississippi and Saint Croix Rivers from the Dakota and Ojibwe to the U.S. government. With more private citizens arriving in the vicinity, the US military took the opportunity to conduct a survey that expanded the military reservation and expelled the squatters who had been allowed to live on the reservation without legal standing since its creation. The unsanctioned settlement was significant and expanded beyond the core group of Selkirkers. The settlement had grown to include 150 families by the time the military expelled them in 1838.

After soldiers from Fort Snelling burned their homes on the military reservation, the settlers moved just outside its borders, about four miles down the Mississippi River to Fountain Cave, where a fellow squatter had erected a makeshift tavern and was using water flowing through the cave to distil whiskey. The entrepreneurial tavern keeper was Pierre Parrant, a fur trader-turned-bootlegger who had most recently made a living on the military reservation selling illegal liquor to indigenous people, soldiers, and fellow settlers. Given he wore a patch over a blind eye that some thought resembled a pig’s eye, he was commonly known as Pig’s Eye, and so too was the settlement that grew up around his tavern. The name, although colorful, did not endure. In 1841, a Catholic Priest named Lucien Gaultier arrived at Pig’s Eye and constructed a log cabin church he named the Chapel of Saint Paul. Shortly thereafter, the community adopted the more acceptable name of Saint Paul as its population quickly increased. When Minnesota became a territory in 1849, it named Saint Paul its capital city.

As Saint Paul expanded, so too did other early Minnesota communities located along rivers within the 1837 cessions. Lumber interests founded Marine Mills (today, Marine on Saint Croix) in 1839, as well as Stillwater just a bit later and just a bit further south. Having staked a claim on the east side of the Falls of St Anthony in 1838, Franklin Steele, a storekeeper at Fort Snelling, began developing milling interests in the 1840s, where the community of Saint Anthony developed before merging with Minneapolis.

Throughout the territory acquired by the United States in 1837 and especially around Fort Snelling, Mendota, and Saint Paul, things changed quickly. Euro-American populations were increasing; traders moved from a trade in furs to what was sometimes called the “Indian business” – trade connected to money brought into the region through federal annuity payments made to the Dakota and Ojibwe for lands ceded through treaties. Furthermore, some traders and military officers began ending marital unions they had entered into with Dakota women, in many cases abandoning their families and remarrying Euro-American women. The multicultural, fluid atmosphere that had existed was transforming into something more rigid. When Minnesota became a territory, this process quickened.

Treaty Making in Minnesota

A big part of the pre-territorial, territorial, and early statehood history of Minnesota is tied to how treaties were used by the United States to acquire territory from the Dakota and Ojibwe people. This story, which spanned most of the 19th century, is discussed in the following chapter.

Minnesota Territory

Section Highlights

- The 1848 convention in Stillwater was an important step in Minnesota becoming a territory in 1849.

- An 1849 census declared that there were 4,535 Euro-Americans in Minnesota territory – mostly congregated in St. Paul, Stillwater, St Anthony, and Pembina. An estimated 32,000 indigenous people lived in the territory.

- The Euro-American population exploded in the 1850s, growing to 172,072 in 1860.

- Schools, hospitals, and newspapers all developed along with the growing population.

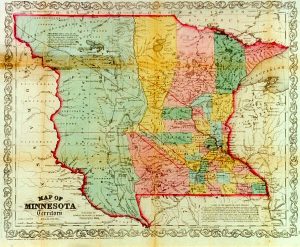

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 established the process for bringing the unorganized territory north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi River into the nation on equal footing as the original 13 states. Ratified that same year, the US Constitution granted Congress the power to admit states beyond the Northwest Territory. The process methodically moved regions from an unorganized status to an organized territory, and eventually to statehood. During the 19th century, this process was fluid, and maps changed often. Portions of the growing nation were usually part of several different territories before reaching statehood. What became the state of Minnesota was at some point a part of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa Territories before being designated as its own territory in 1849. Additionally, territories were typically larger than the states derived from them (as was the case with Minnesota). This created maps that constantly changed throughout the 19th century.

Caught up in the enthusiasm of Manifest Destiny, Euro-American Minnesotans began pushing to be formally organized as a territory in the middle of the 1840s. In 1848, 61 men met in Stillwater and agreed to send Henry Sibley to Washington to petition Congress for the creation of a Minnesota Territory. Sibley allied with Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas, who had previously lobbied to keep the region out of the newly minted states of Iowa (1846) and Wisconsin (1848). Although almost certainly lacking the required 5,000 Euro-American citizens required for territorial status, Minnesota became a territory by an Act of Congress signed by President Polk on March 3, 1849. Polk dispatched Alexander Ramsey, a Whig politician from Pennsylvania, to the new territory to serve as its governor. Ramsey came to make his political career and live the rest of his life in Minnesota.

The new territory stretched from the Mississippi and Saint Croix rivers in the east to the Missouri River in the west, and from Iowa in the south to the international border in the north. A census conducted during the summer of 1849 set the Euro-American population at 4,535. But this number was almost certainly inflated and included what historian Annette Atkins called “facts and guesses.” Conveniently, census takers determined that people of mixed ethnicity, most probably about 1/3 of the total number, were Euro-American if they “dressed and lived in the European fashion.” The Euro-American population in 1849 was congregated in the port town of Saint Paul, the lumbering community of Stillwater, and the developing sawmilling town at St. Anthony – all relatively close to each other and within the boundaries of the 1837 cessions. In addition, the census takers counted nearly everyone living in the Metis community of Pembina located in the far northeast along the Red River and connected to St. Paul by ox cart trails. The census completely ignored the estimated 32,000 Dakota, Ojibwe, and Ho-Chunk people who dwarfed the tiny Euro-American population.[4]

Territorial status quickened the pace of change. Despite the often retold story of the gold rush and population increases in California during the 1850s, between 1849 and 1858, Minnesota was the fastest-growing place in the country. Saint Paul doubled its population in just three weeks after becoming the territorial capital – over the decade, its population grew from 900 to 10,000. In 1851, treaties with the Dakota opened southern Minnesota to Euro-American settlement, and shortly afterward, treaties with the Ojibwe did the same in the north. While indigenous people were confined to treaty-mandated reservations, the Euro-American population and settlement of Minnesota spiked. By the time Minnesota achieved statehood in 1858, it housed nearly 18,000 farms, most established on land acquired from the 1851 Dakota treaties. Perhaps most shocking was the increase in the Euro-American population in Minnesota that grew from 6,077 in 1850 to 172,072 in 1860 – a staggering increase of 2,813%.

With the massive increase in population came the establishment of infrastructure to go along with it. In 1847, Harriet Bishop arrived and opened a school for Saint Paul’s first seven students. Two years later, the territorial legislature established school districts and promised free public education to anyone between the ages of 4 and 21. They also chartered a university and established the historical society. In 1856, Hamline University opened its doors in Red Wing as the first four-year college in Minnesota, open to both men and women. Two years earlier, in 1854, the Sisters of Saint Joseph opened the first hospital in Saint Paul. Also significant were the nearly 30 banks and more than 80 newspapers established during the territorial period.

Conclusion

The arrival of the United States changed everything in Minnesota. By the time the U.S. military constructed Fort Snelling at the confluence of the Mississippi and the Minnesota rivers in the early 1820s, the area had overtaken the Grand Portage as the most significant contact point between indigenous people and newly arriving Euro-Americans. Initially, the fur trade continued under the American Fur Company, largely administered through its headquarters at Mendota. The trade, as it always had, depended on the cooperation between its traders and their indigenous partners. But the goals the United States brought to the region differed from what the French and then the British had wanted. While the Europeans were content to continue the economic relationship through trade, the United States wanted to own the land and settle it with Euro-Americans.

To make this vision a reality, the U.S. government acquired the land through numerous and problematic treaties that forced Dakota and Ojibwe people onto reservations against their will. With the Dakota and Ojibwe confined to reservations and subjected to assimilation policies pushed by the federal government and private missionaries, the newly acquired land filled quickly with Euro-American settlers. As Minnesota prepared for statehood, sectionalism at the national level and the dismal treatment of the Dakota people at a regional level would soon lead to devastating conflicts.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Becker, Jayne. “Ramsey, Alexander (1815–1903).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/ramsey-alexander-1815-1903 (accessed January 24, 2022).

Decarlo, Peter. Fort Snelling at Bdote: A Brief History. St Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2016.

Farber, Zac. “Taliaferro, Lawrence (1794‒1871).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/taliaferro-lawrence-1794-1871 (accessed January 24, 2022).

Gilman, Rhoda. “Sibley, Henry H. (1811–1891).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/sibley-henry-h-1811-1891 (accessed January 24, 2022).

Gilman, Rhoda A. “Territorial Imperative: How Minnesota Became the 32nd State.” Minnesota History (Winter, 1998-99): 155-171.

Vaughan, Margaret. “Métis in Minnesota.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/m-tis-minnesota (accessed January 24, 2022).

Wingerd, Mary. “Bishop, Harriet E. (1817–1883).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/bishop-harriet-e-1817-1883 (accessed January 24, 2022).

- Peter Decarlo, Fort Snelling at Bdote: A Brief History (Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2016), 29. ↵

- Mary Wingerd, North Country: The Making of Minnesota (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 95. ↵

- Decarlo, Fort Snelling at Bdote, 37. ↵

- Annette Atkins, Creating Minnesota: A History from the Inside Out. (St Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007), 39; Rhoda A. Gilman, “Territorial Imperative: How Minnesota Became the 32nd State.” Minnesota History (Winter, 1998-99): 158. ↵

Bravery at the Battle of Tippecanoe and during the War of 1812 distinguished the military career of Colonel Josiah Snelling, but he is best known for commanding Fort Snelling in the 1820s. It was the first permanent U.S. government outpost in what would become the state of Minnesota.

Sarah Shirey, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/snelling-josiah-1782-1828

Lawrence Taliaferro, the wealthy scion of a politically connected, slave-owning Virginia family, was the US government’s main agent to the Native people of the upper Mississippi in the 1820s and 1830s. He earned the trust of Dakota, Ojibwe, Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), Menominee, Sauk (Sac), and Meskwaki (Fox) leaders through lavish gifts, intermarriage, and his zeal for battling predatory fur traders. In a series of treaties, he persuaded these leaders to cede tracts of land in exchange for promises that the government would later break.

Zac Farber, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/taliaferro-lawrence-1794-1871

The Selkirk Colony or Red River Settlement was established in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, the 5th Earl of Selkirk on a 120,000 square-mile track centered at present-day Winnipeg. The colony was populated mainly by Scottish Highlander and Irish immigrants along with people of mix American-Indian and European ancestry. The colony struggled and many settlers left by way of Pembina, then ox cart trail to the Fort Snelling area in the late 1820s and throughout the 1830s. Many of the families expelled from the Fort Snelling military reservation who then settled Saint Paul were from the Selkirk Colony.

Henry Hastings Sibley occupied the stage of Minnesota history for fifty-six active years. He was the territory's first representative in Congress (1849–1853) and the state's first governor (1858–1860). In 1862 he led a volunteer army against the Dakota under Ta Oyate Duta (His Red Nation, also known as Little Crow). After his victory at Wood Lake and his rescue of more than two hundred white prisoners, he was made a brigadier general in the Union Army.

Rhoda Gillman, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/sibley-henry-h-1811-1891

African Americans Dred Scott and Harriet Robinson Scott lived at Fort Snelling in the 1830s as enslaved people. Both the Northwest Ordinance (1787) and the Missouri Compromise (1820) prohibited slavery in the area, but slavery existed there even so. In the 1840s the Scotts sued for their freedom, arguing that having lived in “free territory” made them free. The 1857 Supreme Court decision that grew out of their suit moved the U.S. closer to civil war.

Annette Atkins, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/dred-and-harriet-scott-minnesota

Marine Mill, the first commercial sawmill in Minnesota, operated in Marine Mills (Marine on St. Croix) along the banks of the St. Croix River from 1839 to 1895. Over a period of about six decades, the mill produced millions of board feet of lumber and provided construction material used in towns and cities throughout the state. The remaining ruins were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970 and opened to the public as a park and historic site two years later. The Marine on St. Croix Historic District, created in 1974, includes the mill’s remains.

Eric Hankin-Redmon, MNOPEDIA, https://www3.mnhs.org/mnopedia/search/index/structure/marine-mill-marine-st-croix

Alexander Ramsey was Minnesota’s first territorial governor (1849–1853), second state governor (1860–1863), and a US senator (1864–1875). Although he directly contributed to the founding and the growth of Minnesota, he also played a major role in removing the area's Indigenous people—the Dakota and Ojibwe—from their homelands.

Jayne Becker, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/ramsey-alexander-1815-1903

Pembina was an area in northwest Minnesota, northeast North Dakota and Manitoba, Canada. A metis culture of people of mix European and American Indian ancestry developed in the area. Four-hundred-mile-long ox cart trails connected Pembina to St Paul, which the metis used to transport furs, buffalo hides, pemmican, tallow and other handmade items for trade. Today, the city and county of Pembina are located in the northeastern-most corner of North Dakota.

In 1848 the U.S. government removed the Ho Chunk people, who initially lived in what today is Wisconsin, from a newly created reservation in northern Iowa to Long Prairie in Minnesota Territory. In 1855, another treaty moved the Ho Chunk to a reservation in Blue Earth County in southern Minnesota. Then, in 1863 new treaty moved the Ho Chunk out of Minnesota first to Crow Creek, South Dakota and then to Nebraska.

Harriet Bishop, best known as the founder of St. Paul’s first public and Sunday schools, was also a social reformer, land agent, and writer. In the 1840s, she led a vanguard of white, middle-class, Protestant women who sought to bring “moral order” to the multi-cultural fur-trade society of pre-territorial Minnesota.

Mary Wingerd, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/bishop-harriet-e-1817-1883