15 The Times They Are A Changin’: The Antiwar Movement and Identity Politics – 1965-1980

Just as the Black Power Movement captured the attention of the nation’s cities in the middle of the 1960s, opposition to American involvement in Southeast Asia escalated. Soon, increasingly confrontational student antiwar protests destabilized college campuses across Minnesota and the nation. Other marginalized groups – American Indians, women, Latinos, gays and lesbians – followed the example and tactics of the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Antiwar movements to advocate for their own causes. It seemed to many older Americans who had endured the Great Depression and fought World War II that their children were ripping the country apart from within.

In Minnesota, all of these groups – from American Indian activists to gay and lesbian advocates – had important connections to the wider struggles going on at the national level. They were also driven by more local concerns and issues that provided a set of unique experiences during the turbulent era of Civil Rights, Antiwar protests, and the emergence of Identity Politics. As did activists across the nation, Minnesotans stood up for what they believed in and helped make change during a chaotic period in our history.

The Times They Are A-Changin’

Come mothers and fathers throughout the land – and don’t criticize what you can’t understand – your sons and your daughters are beyond your command – your old road is rapidly agin’ – please get out of the new one If you can’t lend your hand – for the times they are a-changin’ -Bob Dylan, 1964

A number of Minnesotan politicians and activists played important national roles during the 1960s and 1970s. Among the most prominent was singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, whose music came to epitomize the character of the Civil Rights and Antiwar Movements.

Robert Allen Zimmerman was born in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1941, but moved with his family to the iron range town of Hibbing when he was six. After moving to Minneapolis and enrolling in the University of Minnesota in 1959, he began introducing himself as Bob Dylan while playing American Folk music at several venues around Dinkytown – a neighborhood adjacent to the university. By May of 1960, he had dropped out of the university, and the following January, he left Minnesota for New York. He went on to record protest songs that came to define the social unrest of the 1960s and 1970s, including: Blowin’ in the Wind (1963); The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964). Since the 1960s, for over 50 years, Dylan has continued to write and record music. He has sold over 100 million albums and remains one of the best-selling artists of all time. In 2024, the biopic, A Complete Unknown, chronicled Dylan’s early history in the New York Folk Music scene through his controversial decision to use electric instruments at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965.

The Antiwar Movement

During the mid-1960s, large numbers of Baby Boomers (the post-World War II generation) entered the nation’s colleges and universities. As they did, many began to feel disconnected from their parents and questioned some of the assumptions and beliefs by which the preceding generation lived their lives. Their parents had endured the Great Depression, fought World War II, and created a post-war economic boom that laid the foundation for our current economy. Many built nondescript homes in the suburbs and raised their children in comfortable, consumer-driven, and conforming surroundings. Their experiences during the depression and the war had developed a deeply held sense of patriotism and trust in the government.

As baby Boomers reached young adulthood, they brought with them completely different childhood experiences, faced a world much changed since the 1940s, and watched as the federal government struggled with domestic unrest and an uncertain Cold War foreign policy. Gone were their parents’ blind trust in government and the willingness to conform – a notable generation gap had emerged.

Nothing exacerbated this generation gap as much as did the Vietnam War. As the war escalated into the late 1960s, opposition to it grew across all segments of the population, but young adults – and those in college especially – moved to the forefront of an increasingly confrontational Antiwar Protest Movement. Meanwhile, many of their parents held true to their beliefs in the honor of unquestioning service to their country and trust in the government.

In late 1969, the government instituted a draft lottery and, in 1971, had ended deferments granted to students enrolled in college. These significant adjustments in the conscription process corresponded with increased antiwar protest activity on campuses in Minnesota and across the country.

Baby Boomers at the Forefront of the Antiwar Movement

Section Highlights

- As US involvement in Vietnam escalated, college students in Minnesota and across the nation led an Antiwar Movement.

- Arrested while attempting to destroy draft cards, seven of the “Minnesota Eight” were sentenced to five-year prison terms in a highly publicized trial.

- Student protests at the University of Minnesota became confrontational and violent by the early 1970s.

As American involvement in Vietnam escalated during the mid-1960s, so too did civilian opposition to the controversial war effort. Although people from all segments of American society came to oppose the war, baby boomers led a burgeoning Antiwar Movement that clashed, at times violently, with the U.S. government and with many of the ideals of their parents’ generation. The Free Speech Movement that developed on the University of California-Berkeley campus in the fall of 1964 demanded “participatory democracy” – a larger role in the political decision-making that directly impacted the lives of young adults. This sentiment soon spread across the nation’s college campuses and became a confrontational Antiwar Movement. A small but noticeable minority of the baby-boom generation went beyond protesting government policy and formed a counterculture that advocated, not only an end to US involvement in Southeast Asia, but also alternative lifestyles that included mood-altering drugs, rock music, and, in some cases, communal living.

Mirroring antiwar activity on campuses around the country, students around Minnesota took part in the expanding movement. The first peace rally at the state’s largest campus, the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities, took place in February 1965 when 200 protestors addressed a crowd of 4,000. King told the spirited audience that the Vietnam War “divided our country [and] invited hatred, bigotry, and violence” while “diverting attention from civil rights.”

As neighborhoods bordering the University developed counter-culture communities, the Antiwar Movement thrived on campus and spilled over into the larger community. On October 15, 1969, Moratorium Day, 6,000 demonstrators turned out at the university to protest the faltering war effort. Also in 1969, hundreds of students and faculty members from across the state launched Operation Honeywell – an ongoing protest against the Minnesota-based company for their use of university research in the production of cluster bombs. Highlighting the polarization of the nation, Honeywell responded by stating that the company “was proud to provide our troops with necessary weapons.”

For some members of the Minnesota Conspiracy to Save Lives, antiwar activities went beyond protesting. In January 1970, several members broke into the Saint Paul post office, destroyed draft cards, and stole 1200 draft stamps (used to indicate that service had been fulfilled when placed on draft cards). The raid was one of the largest of the war and convinced Federal Bureau of Investigation chief J. Edgar Hoover to dispatch 100 agents to Minnesota. Additional break-ins followed until FBI agents caught up with eight burglars, all with ties to the University of Minnesota, as they attempted to break in and destroy draft cards in the selective service offices in Little Falls, Alexandria, and Winona. Three days after the Minnesota Eight’s arrests, riots rocked Minneapolis. In the highly publicized trials that followed, seven of the eight were tried for burglary, convicted, and sentenced to five-year prison terms.

The Minnesota Eight

- Seven members of the Minnesota Eight, approximately 1970.

- Seven members of the Minnesota Eight, 2007

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

By the early 1970s, the Antiwar Movement had permeated college campuses in all corners of the country and had become reactive to the federal government’s foreign policy actions. When President Nixon ordered US troops into Cambodia on April 30, 1970, campuses exploded in protest. Just days later, on May 4th, National Guard troops shot into crowds of students at Kent State University in Ohio and killed four. On the same day, 5,000 University of Minnesota students and faculty had voted to strike in protest of the Cambodia invasion. As news of the shootings at Kent State spread, the university entered a week of protests that included a memorial, building occupations, pickets, and rallies. On Saturday, May 9th, students from Augsburg, Macalester, Saint Thomas, Hamline, Saint Catherine’s, and Concordia joined University of Minnesota students in a march to the state capitol in Saint Paul. Similar protests occurred on campuses all over the state. After a heated debate at the Moorhead campus of the state university system, students voted by a margin of two-to-one in favor of a three-day strike.

Although University of Minnesota President Malcolm Moos received praise for his handling of campus unrest in the spring of 1970, two years later, events spiraled out of his control. President Nixon’s decision to mine Haiphong Harbor in North Vietnam brought renewed campus activism in May 1972. Police arrested dozens of student protestors on outstate campuses of the state university system at Mankato and Marshall. At the University of Minnesota, the escalation sparked over a week of demonstrations beginning on May 9th that became the most violent in the university’s history. On May 10th, rowdy demonstrators, fires, and rumors that the armory was to be torched convinced the university to call Minneapolis riot police on campus. Outside of the control of university officials, the police used nightsticks, mace, and tear gas sprayed from a helicopter in attempts to disperse the increasingly hostile demonstrators. By early the next morning, the National Guard arrived on campus and brought a calming effect on the police-student standoff. Regardless, the following days saw massive rallies, sporadic fires and explosions, and students blocking traffic around campus and on nearby Interstate 94. Slowly, the University reestablished order and attempted to address student concerns by holding teach-ins on May 17th and 18th.

Student Protests at the University of Minnesota – May, 1972

Star Tribune Photographs.

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

The violent unrest at the University of Minnesota in May 1972 was part of the last round of student antiwar protests that rattled the country. In 1973, President Nixon withdrew US combat troop from Vietnam and college campuses across the country quieted. In Minnesota and across the nation, the Antiwar Movement clearly impacted the country’s foreign policy, and its confrontational tactics served as a catalyst for other identity-based groups and causes.

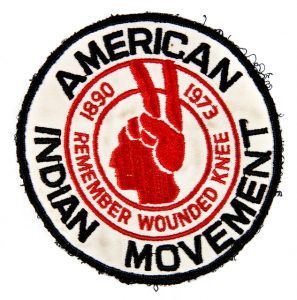

Red Power: The American Indian Movement

During the 1960s, American Indians in Minnesota and throughout the nation adopted the strategies of the Civil Rights and Antiwar protest movements to draw attention to systemic discrimination and to advocate for more equal treatment. The Minneapolis-based American Indian Movement (AIM), founded in July 1968, began as a local attempt to improve American Indian living conditions in the Twin Cities but quickly grew to lead a national “Red Power” movement that advocated equal rights for all American Indian people.

Postwar Federal Policy

Section Highlights

- Post World War II federal policy encouraged American Indians to relocate to urban areas.

- In 1953, Public Law 280 transferred criminal and civil jurisdiction from the federal to the state level in several states, including Minnesota.

- The urban American Indian populations of Duluth, St. Paul, and Minneapolis increased significantly after 1950.

Post-World War II federal policy concerning indigenous people attempted to dismantle federal recognition of indigenous nations and encourage American Indians to leave poverty-stricken reservations and rural areas for employment opportunities in the nation’s cities. Officially enacted by Congress in 1953, the policy of Termination attempted to sever the federal government’s relationship with indigenous nations and “to make Indians within the territorial limits of the United States subject to the same laws and entitled to the same privileges and responsibilities as are applicable to other citizens of the United States.” As part of the Termination effort, Congress also passed Public Law 280 in 1953, transferring criminal and civil jurisdiction of tribal lands from the Federal government to the state governments. Congress made the legislation mandatory in five existing states (California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, and Wisconsin) and extended it to Alaska once it reached statehood. In Minnesota, the new policy impacted all indigenous people living in the state with the exception of the Red Lake Ojibwe, who had lobbied successfully to be left out of the legislation.

A government effort to encourage indigenous people to move from reservations to cities in hopes of acquiring better jobs, housing, and self-sufficiency also played a role in the Termination Policy. In the early 1950s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs began programs aimed at encouraging indigenous people to relocate to urban centers. In 1956, Congress furthered this effort by passing the Indian Relocation Act, which provided vocational training for urban indigenous people between the ages of 18 and 35. These programs and non-government-sponsored migration resulted in a significant shift in indigenous demographics – urban populations swelled. In 1940, prior to these government efforts, only 8% of the indigenous population lived in urban areas; by 2000, 79% of American Indians lived in cities.

Indigenous demographics in Minnesota mirrored what was happening across the country: populations increased and became more urban. In 1950, only 589 of the 12,528 indigenous people in Minnesota lived in Minneapolis and St. Paul. As the total indigenous population in the state increased, the percentage living in the state’s largest metropolitan area increased even faster. By 1960, the indigenous population of the Twin Cities had climbed to 3,085; by 1970, it reached 9,578. Of the 49,392 indigenous people living in Minnesota in 1990, nearly 40% lived in the core urban centers of Minneapolis (12,335), St. Paul (3,697), or Duluth (1,837).

Minneapolis and the Origin of the American Indian Movement

Section Highlights

- Indigenous Activists formed the American Indian Movement in Minneapolis in 1968.

- Initially, the organization focused its efforts on addressing local issues facing the indigenous community.

- AIM created the AIM Patrol, Indian Health Board, Legal Rights Center, and survival schools in Minneapolis and St Paul.

- AIM leaders became involved in confrontational protests outside of Minnesota, including Alcatraz and Mount Rushmore.

- AIM activists occupied the Twin Cities Naval Air Station in 1971.

As the urban population of indigenous people swelled in Minneapolis, so, too, did poverty, inadequate education, poor housing, unemployment, discrimination, and allegations of police brutality. Taking their cue from other protest movements of the period, Minneapolis American Indian activists Clyde Bellecourt, Dennis Banks, and George Mitchell organized a meeting of about 100 people in North Minneapolis on July 29, 1968. They created what they initially called Concerned Indian Americans (CIA). Within weeks, the organization changed its name to the American Indian Movement (AIM) and established an office in the city’s Phillips neighborhood – the heart of its American Indian community.

Initially, AIM focused its sparse resources on local issues facing indigenous people living in Minneapolis: discrimination, police brutality, lack of effective social services, and inadequate legal representation. AIM began to file discrimination lawsuits on behalf of American Indians and organized the AIM Patrol to monitor police activities in their communities. AIM Patrol members monitored police radios, used two-way radios to communicate, and patrolled the Phillips neighborhood in visible red cars. Armed with cameras and tape recorders, the AIM Patrol began documenting encounters between police and American Indian citizens.

In 1969, AIM helped create the Indian Health Board – the first urban-based health care service for American Indians. The following year, utilizing the expertise of paid and volunteer attorneys, AIM created the Legal Rights Center that began to provide free legal services for indigenous people in Minneapolis. By the early 1970s, AIM’s Franklin Avenue storefront office became a place where the Minneapolis indigenous community could turn to for help with a variety of challenges – from transportation to loans to legal assistance. At that time, an AIM chapter in St. Paul was operating under the leadership of Pat Bellanger and Eddie Benton-Banai.

On January 3, 1972, AIM opened the American Indian Movement Survival School in the basement of its Franklin Avenue office to its first two students. The school went on to take advantage of funding provided by the Indian Education Act of 1972 and became the Heart of the Earth Survival School. It operated for nearly 40 years, educating over 10,000 American Indian students, before being forced to shut its doors in the face of an embezzlement scandal involving its director in 2008. In the Frogtown neighborhood of Saint Paul, the Little Red School House Survival School also opened its doors in 1972 and operated with an emphasis on American Indian language and culture until 1990.

AIM also attempted to draw attention to government violations of indigenous treaty rights in Minnesota and beyond. In November 1969, indigenous activists occupied Alcatraz, an abandoned federal prison in San Francisco Bay. The group, Indians of All Tribes (IAT), claimed that the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty returned all abandoned, out-of-use, and retired federal lands to indigenous nations. Since the federal government had closed the prison and abandoned the island, IAT claimed it for all Indian peoples. In December, an AIM leadership contingent visited the occupied island for several weeks before returning to Minneapolis, trained in the tactics of direct confrontation and land seizure. The occupation lasted for 14 months before federal marshals, FBI agents, and police took control of the island and ended the occupation. The following summer, AIM leaders Banks and Russell Means traveled to South Dakota to participate in the occupation of Mount Rushmore. Protesters demanded that the federal government return the Black Hills to the Lakota people (also mandated in the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie).

The following spring, on May 17, 1971, AIM employed similar reasoning and tactics when it occupied the Naval Air Station at the Minneapolis/St. Paul International Airport. Since the base was in the process of being decommissioned, AIM claimed ownership. AIM leaders planned to open an indigenous survival school on the abandoned base. Negotiations continued for four days before federal marshals stormed the base and arrested several of the occupiers, including Banks, Bellecourt, and Means. While the occupations of Alcatraz, Mount Rushmore, and the Twin Cities Naval Air Station did not result in any government concessions, they did raise the national consciousness about indigenous treaty rights issues.

Minneapolis and the Origin of AIM

- On May 17, 1971, AIM activists climbed over the fence at the Twin Cities Naval Air Station to begin their takeover of the base. Minneapolis Star photo

- After the occupation of the Twin Cities Naval Air Station had ended, AIM leaders held a news conference with U.S. Senator Walter Mondale (right). AIM co-founder Dennis Banks is at the microphone. Co-founder Clyde Bellecourt is seated on the left. Minneapolis Tribune photo. 1971.

- In 1980, these students learned a traditional indigenous game at the Red School House in Saint Paul.

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

Confrontational Politics in Minnesota and Beyond

Section Highlights

- By the early 1970s, AIM emerged as a national movement.

- Threatened violence during the 1972 AIM National Conference held on the Leech Lake Reservation was narrowly averted.

- AIM demonstrated in Gordon, NE, after the murder of Raymond Yellow Thunder in 1972, and in Custer, SD, after the murder of Wesley Bad Heart Bull in 1973.

- In 1972, the Trail of Broken Treaties ended with the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs offices in Washington, DC.

- In 1973, the 71-day standoff at Wounded Knee ended with two activists and one US Marshal killed.

By the spring of 1972, AIM had grown into a national movement that was talking publicly about more aggressive tactics that hinted at violence. The organization had decided to hold its second national convention on the Leech Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota on the weekend that the state opened its walleye fishing season. When the nearly 900 AIM activists arrived – some of them armed – leaders threatened to blockade roads to stop sports fishermen from reaching lakes located on reservation lands. At the urging of local Ojibwe leaders (who had just won a controversial legal case confirming their rights to fish, hunt, and gather wild rice on their reservation outside of state regulation), AIM agreed to open the roads, and the tense situation subsided (See Movie 14.2). But the threats and firearms had served their purpose – AIM gained more notoriety as a potentially violent advocate for American Indian Rights. Several days after the averted standoff, Means announced in a press conference that “confrontational politics” was now the official policy of AIM and suggested that violence might come soon.

Television News Coverage of the 1972 AIM Convention at Cass Lake, Minnesota

AIM held its 1972 National Convention at Cass Lake, a small city located within the borders of the Leech Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota. The convention was held on the opening weekend of the sport fishing season, and AIM’s threats of blockading roads leading to popular fishing lakes brought controversy. News coverage focused on the impact the threatened blockade and potential violence had on the fishing opener. As you view this newscast, understand that it is a product of its time. Does it present a balanced account of the events? Is the use of the phrase “too many chiefs and not enough Indians” appropriate? What does the tone of the report tell us about the context of white Indian relations in the early 1970s?

Reporter Roger Huff stands outside Cass Lake during the American Indian Movement Convention. He reports on how the media is being treated and forced off of tribal lands by AIM members. Hubbard Broadcasting Corporation, KSTP Television (Channel 5). June 8, 1966. KSTP-TV Archive, Minnesota Historical Society. 27291

Also in the early 1970s, AIM began to play a leading role in indigenous rights issues beyond Minnesota. Means later recalled that “AIM had decided on a policy. We would advocate for any Indian man or woman, any Indian family, any Indian community, or any Indian nation. All they had to do was call us, and we would respond.” After justice seemed to stall in the wake of the murder of Yellow Thunder in Gordon, Nebraska (a town just south of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota), his family members contacted AIM for assistance. AIM descended on the city, demonstrated, brought attention to Yellow Thunder’s murder, and prompted state and federal authorities to take an interest in the case that ultimately brought convictions of the four white murderers involved in his death.

In October 1972, AIM met with seven other national indigenous organizations in Denver, Colorado, and planned “The Trail of Broken Treaties Caravan” – a protest caravan that would bring indigenous protesters and concerns from across the country to Washington, D.C. Caravans formed in the West Coast cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle and reached Saint Paul on October 23. While in the Twin Cities, caravan participants drafted a Twenty-Point Position Paper to be delivered to the president upon the group’s arrival in Washington, D.C. On November 2, the caravan arrived in the nation’s capital and, after the Nixon Administration refused to meet with them, occupied the offices of the Bureau of Indian Affairs during the week of the presidential election. On November 9, the protesters agreed to leave after vague promises from the Nixon Administration to review their position paper and receipt of $66,000 to offset the costs of returning to their homes. In the end, the Nixon Administration rejected the proposals in the Twenty-Point Position Paper, but once again, AIM and its allies had successfully captured the attention of the nation.

Just months after the BIA occupation, AIM continued to gain headlines in protests at Custer, South Dakota, and the occupation of Wounded Knee. In January 1973, Darld Schmitz stabbed Wesley Bad Heart Bull during a scuffle outside a bar just miles from the Pine Ridge Reservation. When prosecutors refused to seek a first-degree murder indictment, AIM coordinated a protest at Custer, South Dakota, in response. An angry confrontation turned violent – activists destroyed two police cruisers, burned the chamber of commerce building, and attempted to do the same to the courthouse. Police arrested 22 people, including the victim’s mother, Sarah Bad Heart Bull, along with Banks and Means. Three weeks later, AIM led 200 activists and occupied Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation. By far the most confrontational of all AIM protests, the occupation lasted 71 days and ended with two activists and one US Marshal killed.

AIM Occupation of Wounded Knee, 1973

- AIM leader Russell Means, left and assistant U.S. attorney general Kent Frizzell sign settlement of the Wounded Knee problem April 5, 1973 in South Dakota. Looking on left is Frizzells assistant Richard Helstern and AIM leader Dennis Banks. (AP Photo)

- American Indian Movement leader Dennis Banks holds an envelope addressed to the Justice Department containing ashes of a federal proposal for Indians to evacuate Wounded Knee, on March 5, 1973. Russell Means, center, and Carter Camp look on. (AP Photo)

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

AIM always had its detractors and those who felt it was harming indigenous progress, but it certainly brought indigenous concerns, including those of urban populations, to the forefront of the nation’s consciousness. In 1973, the American Indian Press Association summed up AIM’s contribution to the drive for American Indian rights when it wrote, “they are respected by many, hated by some, but never ignored.”

Beyond Black and White: Other Social Movements

In Minnesota and throughout the nation, other marginalized groups followed the lead of the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Antiwar movements and began to advocate for equal treatment. Some of the most prominent included: the feminist movement, the Chicano Movement, and the Gay Liberation Movement.

Women’s Rights and Liberation in Minnesota

Section Highlights

- Both the Women’s Rights and the Women’s Liberation Movements made great strides in Minnesota and the nation during the 1970s.

- The various groups advocating for women’s causes in the Twin Cities struggled to present a united front.

- Advances toward equality in education were achieved at the primary, secondary, and postsecondary levels.

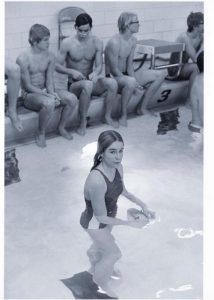

- Minnesota girls fought for equal access to school-sponsored sporting opportunities as Title IX was leveling the playing field nationwide.

During the 1960s, women organized and accelerated a long tradition of political advocacy that had waned a bit since they had gained the right to vote in 1920. In 1966, Betty Friedan and other activists organized the National Organization for Women (NOW) and began advocating for causes affecting women’s lives, including gender equality in the workplace, support of the Equal Rights Amendment, equal access to education, development of gender studies programs at colleges and universities, and support of reproductive rights. Scholars have labeled the branch of the movement led by NOW as the “Women’s Rights” or “Reform” movement.

By the late 1960s, frustrated with the pace of change in the emerging movement and legislative focus of NOW, some younger women adopted more confrontational tactics to draw attention to the inequalities faced by women. Many of the activists in what became known as the Women’s Liberation Movement (seen as more radical than the reform movement led by NOW) were veterans of the Civil Rights and Antiwar protest movements. They had grown tired of the sexist treatment they received not only in the public sphere but also within protest movements themselves. In Minnesota and across the nation, women from a variety of backgrounds and circumstances became part of the fluid, multifaceted Women’s Rights and Liberation Movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

By the fall of 1970, when NOW established a chapter in the Twin Cities (TCNOW), the Women’s Liberation Movement in Minneapolis and St. Paul was well under way. Earlier that year, the Twin Cities Female Liberation Group (TCFLG) opened an office in Minneapolis’s Dinkytown, began publishing a newsletter, and serving as a “politically impartial umbrella group,” attempting to coordinate the variety of groups, causes, and activities that had already emerged in the metropolitan area into a united women’s movement. On August 26, 1971, members of the TCFLG joined activists from the Women’s Counseling Service (established in 1970) and other groups in Strike Day. Urging women across the Twin Cities to skip work, the women hung a banner from the observation deck of the Foshay Tower in Minneapolis reading “WOMEN UNITE,” distributed leaflets, and performed guerrilla theatre in the Nicollet Mall.

Despite an impressive amount of protesting, demonstrating, publishing, marching, and organizing by dozens of groups, the movement proved too diverse to unite under TCFLG, and the organization splintered and finally dissolved in April 1971. In the absence of TCFLG, the Twin Cities movement met with further division but also scored impressive successes. In the fall of 1971, the women’s monthly Gold Flower appeared, and the Minnesota Women’s Political Caucus formed. But at the caucus’s second conference in January 1972, lesbian activists heckled keynote speaker and NOW founder, Friedan, questioning the author’s well-known anti-gay and anti-lesbian views. Gold Flower reported that the meeting dissolved into “a near riot.”

Despite the formation of a second umbrella organization, the Twin Cities Women’s Union, in 1972, divisions within the movement continued to intensify throughout the 1970s, as dozens of smaller, more focused groups worked individually to advance specific causes. These groups developed counseling services, health care services, radio shows, theater, art, literature, and a variety of other support services for women. In just one example, women in St. Paul worked to establish phone counseling for women focused on domestic abuse, family law, health care, and other areas. Their efforts expanded, and, in the mid-1970s, the group opened the Women’s Advocates House, the first shelter for battered women in the nation. In 1977, a similar facility, the Harriet Tubman Women’s Shelter, opened in Minneapolis.

As Women’s Liberation activists worked in the Twin Cities, achievements at the state and national level advanced their cause in education and impacted girls and women in Minnesota. Since the establishment of continuing education courses for women at the University of Minnesota in 1960, the university has been a national leader in providing educational opportunities for women. When the university established its Women’s Studies program in 1973 (currently the Department of Gender, Women & Sexuality), it reflected a broader change nationwide that saw colleges and universities across the nation offering nearly 30,000 Women’s Studies courses by 1980.

The tide of change also affected younger students. In 1971, NOW activist Charlotte Striebel brought a complaint against the St. Paul Public School District for denying her seventh-grade daughter the opportunity to join the Murray Junior High boys swim team and for offering no alternative. Striebel cited a St. Paul ordinance prohibiting gender discrimination in the schools, and the city’s Human Rights Department concurred. Murray Junior High allowed Kathy Striebel to join the team and eventually established a girls’ swim team; other schools followed its example. In April 1973, a Minneapolis District Court made a similar statewide ruling on behalf of two female student athletes. Toni Pierre, a runner and skier from Hopkins, and Peggy Brenden, a tennis player from St. Cloud, were prohibited from joining their schools’ boys teams (neither school offered girls teams) because the Minnesota High School League barred female athletes from competing against male athletes. The Eighth Court of Appeals found the regulations “arbitrary and unreasonable, in violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.” The ruling complied with the federal law, Title IX, established the previous year but still in the implementation process, which provided that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Two other issues important to women activists across the state and nation, reproductive rights and the Equal Rights Amendment, were also decided at the national level during the 1970s. In a controversial 1973 ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court protected a woman’s right to have an abortion during the first two trimesters of a pregnancy in the landmark Roe v. Wade decision. For nearly fifty years, the decision has remained a decisive issue. In the summer of 2022, a conservative-leaning U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Roe ruling and removed the constitutional right to an abortion in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The reversal left individual states to determine the legality of abortion and, in doing so, jolted the country. While those opposed to abortion celebrated, those supportive of a woman’s right to decide loudly protested. Several states have outlawed abortion, while others are moving in that direction. In other states, including Minnesota, women still have access to an abortion, but it is no longer a right protected by the U.S. Constitution and could be curtailed by future state or national legislation.

The Equal Rights Amendment, which proposed that “equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex,” had first been proposed to Congress in 1923. In 1972, due in part to the advocacy of NOW and other Women’s Rights organizations, the amendment passed Congress and was sent to the states for ratification. While the Minnesota Legislature ratified the amendment in February 1973, the effort eventually fell three states short of the required 38 and failed to gain approval.

The Chicano Movement in Minnesota

Section Highlights

- The destruction of the Lower West Side barrio brought the Chicano Movement to Saint Paul.

- Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church and the Neighborhood House served as important community resources.

- Saint Paul activists successfully fought for more affordable housing on the city’s west side and established various community service organizations.

- A branch of the Brown Berets operated in Saint Paul from 1969 to 1973.

- Activists fought for better access to education and the establishment of the Chicano Studies Department at the University of Minnesota.

The Chicano Movement gained national prominence in the mid-1960s when the United Farm Workers (UFW), an agricultural union of mainly migrant Mexican-American farm workers led by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, organized a strike against grape growers in California. The strike developed into a nationwide boycott that corresponded with a more militant urban-based movement of young Mexican Americans who, adopting the “Chicano” label, demanded civil rights and acknowledgement of their culture and history. In the West, Southwest, and other rural areas, the Chicano Movement, or El Movimiento, demanded protection for agricultural workers. In urban barrios across the country, activists fought for access to adequate education, political participation, and an end to police harassment and discrimination. In the barrio of St. Paul’s Lower West Side, the Chicano Movement made connections with the multifaceted national effort, but emerged from, and focused on, local issues.

Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church

- Young people from Our Lady of Guadalupe Church performing “Mexican Hat Dance” in observance of Pan-American Day. April 1948

- Procession in honor of the Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, St. Paul. December 12, 1950

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

Mexican and Mexican-American migrant workers began to arrive in Minnesota early in the 20th century, primarily working in the sugar beet industry. While many of these families stayed in Minnesota only during the harvest, slowly, some began to settle out and stay in Minnesota permanently. While a few families chose to settle in smaller Minnesota towns, and some went to Minneapolis, most found their way to St. Paul’s Lower West Side and established Minnesota’s first Mexican colonia (colony). Supported by a growing, close-knit community, Mexican-American businesses, the Neighborhood House, and Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church, the Lower West Side barrio flourished and expanded. By 1960, most of the Mexican-American population in Minnesota lived in the Twin Cities, and over half lived in the barrio on the Lower West Side of Saint Paul.

In the early 1960s, city planners targeted the Lower West Side for urban renewal. The subsequent destruction of the colonia brought the Chicano Movement to Minnesota. By 1960, the barrio’s housing stock was inadequate, dilapidated, and overcrowded. Marginalized by the surrounding city, much of the barrio was poverty-stricken and had little voice in the decision-making of the larger urban community. Eight years earlier, in the spring of 1952, the Mississippi River spilled over its banks and soaked the barrio. While spring flooding was not uncommon on the West Side flats, the scope of the 1952 flood was unprecedented and destroyed many homes and businesses. Urban planners considered the flood and what they saw as urban blight as logical reasons to level the neighborhood, build a flood wall, and create the Riverview Industrial Park. Planners’ assumption that the barrio residents would disperse across the larger urban area was proved wrong when 70% of the community stayed on the West Side and relocated just up the bluff to an area known as Concord Terrace. By 1970, the US Census counted 23,198 Mexican-Americans in Minnesota, with 6,512 living in Saint Paul, and most of them still living on the city’s West Side. But the destruction of its neighborhood brought a new sense of activism to the community, now determined to have its voices heard and rights respected.

Pre-dating the emergence of the national Chicano Movement, activists in St. Paul began by addressing local concerns, among the most pressing were adequate housing and social services. By 1963, nearly one-half of the displaced residents had already relocated to Concord Terrace, even as opposition from existing Euro-American residents scuttled city plans to build more affordable housing. But barrio residents became more politically active and used mass demonstrations and attendance at planning meetings to successfully push for the construction of new affordable housing and community rehabilitation. Community efforts resulted in the construction of Dunedin Terrace in 1966 (low income rental units for 1,500 people); the Concord Terrace Renewal Project in 1968 (housing rehabilitation, rezoning to allow for more single family homes, and neighborhood beautification); and the Torre San Miguel Project in 1972 (142 single family homes – the first cooperatively owned low-cost housing development in Minnesota). Additionally, community advocates also established the West Side People’s Health Clinic (La Clinicia) in 1970, the first bilingual health service in Saint Paul. Other community social service agencies included Central Cultural Chicano in 1972, Centro Legal in 1981, and Comunidades Latinas Unidas en Servico (CLUES) in 1981.

As Saint Paul’s local movement made connections with the larger national movement, some younger activists formed a branch of the Brown Berets. The Brown Berets, which formed in East Los Angeles, California, in 1969, took a militant stand against police brutality and discrimination in education and began self-policing their barrio. In 1969, a chapter of Brown Berets formed on the West Side of Saint Paul and had a sporadic existence until 1973. At its height, the chapter included about 50 active male and female members between the ages of 12 and 27. The Brown Berets donned uniforms, held weekly meetings, monitored the West Side neighborhood, supported the grape boycott, advocated for equal access to education, advocated for the development of recreational opportunities, and worked to expand employment opportunities for Saint Paul’s Chicano community. They also performed community service activities such as fundraising, serving as chaperones for children’s activities, raising money for families in need, and even holding educational sessions focusing on drug abuse, employment, and legal assistance. Despite striving for some of the same results, the Brown Berets were shunned by more mainstream Chicano organizations as too militant, and their activists, some of whom had criminal records, were targeted by police. Unable to overcome negative perceptions, Saint Paul’s Brown Berets dissolved in 1973.

Chicano activists believed that improved access to education was an important avenue to empowerment and worked to improve educational opportunities at all levels – from preschool to adult education. Initial efforts originated from Our Lady of Guadalupe Church (which had moved up the bluff along with the barrio) when it established the Guadalupe Elementary School in 1962. Lacking funds and sufficient enrollment, the school was forced to close in 1968. Undeterred, three years later, the parish opened the Mi Cultura Day Care Center, the first Mexican American licensed childcare center in the state. Also in 1971, the Saint Paul Public School District utilized federal funding to create the Mexican-American Cultural and Educational Center. But just four years later, in 1975, when the building that housed the center was condemned as a fire hazard and federal funds dried up, the district abandoned the effort. A variety of migrant agencies also appeared and utilized War on Poverty funding to establish educational programs that focused on English language skills in preschool and adult education.

Mexican Independence Day Parade, Saint Paul – 1971

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

Perhaps the most successful and enduring effort at expanding educational opportunities for Mexican Americans resulted from student efforts at the University of Minnesota. In 1969, just four of the 50,000 students at the University of Minnesota’s Twin Cities Campus were Mexican-American. That year, university students joined others from Macalester College in St. Paul to form the Latin Liberation Front, which began to recruit Chicano students and push the university to establish a Chicano Studies Department. On September 15, 1970, the Latin Liberation Front demonstrated in front of the university’s Morrill Hall, and in October 1971, it occupied the building. The University Regents approved the establishment of the Department of Chicano Studies in February 1972 for the purposes of “providing a course of study designed to acquaint students with the historical and contemporary experience of Chicanos.” By 1978, the department, the first in the nation, included six full-time faculty members.

Gay Pride and Power in Minnesota

Section Highlights

- The Stonewall Riot, which took place in New York City during the summer of 1969, served as a catalyst for the Gay Liberation Movement.

- Weeks before the Stonewall Riot, Fight Repression of Erotic Expression (FREE) formed in Minneapolis.

- Jack Baker and Michael McConnell were among the first same-sex couples nationwide to apply for a marriage license and were perhaps the first to be married in the nation.

- In 2015, the US Supreme Court overturned the 1971 Minnesota Supreme Court ruling in Baker v. Nelson that had defined marriage as a “union between a man and a woman.

On June 28, 1969, gay and lesbian patrons at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York City, took a stand against police harassment and discrimination. Police eventually dispersed the crowd and quelled the riot, only to see a larger crowd of perhaps 1,000 demonstrators gather the following night. To chants of “Gay Power,” the rioters demanded an end to harassment and discrimination and began what became a nationwide Gay Liberation Movement, later the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning (LGBTQ) movement. The next year, on the riot’s anniversary, the first Gay Pride parade took place. By the following year, LGBT advocacy groups operated in every major city in the nation. While LGBT groups certainly existed before the Stonewall Riots, they were not focused on public advocacy for equal treatment. The New York riot served as a catalyst for a new type of advocacy that mirrored other Civil Rights era movements in tactics and rhetoric. It began a visible movement that encouraged its members to be proud and utilize confrontational politics to call attention to its grievances.

Weeks before the Stonewall Riot, the gay community in Minneapolis became one of the first in the nation to organize and begin to publicly advocate for equal treatment. On May 18, 1969, Koreen Phelps and Stephen Ihrig formed Fight Repression of Erotic Expression (FREE) while teaching a “Homosexuality and Revolution” course at Free University, a counterculture educational organization located near the West Bank campus of the University of Minnesota. Phelps saw FREE as a “political militant organization” that hoped, in the words of co-founder Ihrig, to attract “hip, young, gay people here in Minneapolis” in an attempt to confront straight society and challenge legalized discrimination. During the summer of 1969, FREE became an official student organization at the university (the fourth such organization in the nation) and began meeting in the student union. As the fall term began, an active core group numbered around 50 and drew mostly from the university student body but also included members from the surrounding community.

Once on campus, FREE elected first-year law student Jack Baker as its president. Baker and his partner, university librarian Michael McConnell, furthered FREE’s agenda when they applied for a marriage license in May 1970. Denied by Hennepin County, they challenged the decision in the courts and appealed their case to the Minnesota Supreme Court, which in 1971 ruled in Baker v. Nelson that a marriage must be “a union of a man and woman, uniquely involving the procreation and rearing of children within a family.” The US Supreme Court denied consideration of their case in October 1972, citing a “want of a substantial federal question.”

While their case wound its way through the court system, McConnell adopted Baker who changed his name to the gender-neutral Pat Lynn McConnell. The couple then applied and received a marriage license in Mankato, Minnesota. The two were married in September 1971 before Blue Earth County had realized that it had issued a marriage license to a same-sex couple. Baker and McConnell were among the first same-sex couples nationwide to apply for a marriage license and were perhaps the first to be married in the nation.

FREE continued as an organization through 1972, when many of its members formed the Minnesota Gay Activists. Today, the University of Minnesota’s Queer Student Cultural Center identifies a direct connection to FREE and claims it as the group’s founding predecessor.

Baker v. Nelson Overruled

“Baker v. Nelson must be and now is overruled.” – U.S. Supreme Court

In 2012 Minnesota voters turned down a proposed constitutional amendment limiting marriage to a man and a woman. The following year, the state legislature passed and the governor signed the Marriage Equality Act (allowing for same-sex marriages). When the United States Supreme Court ruled “that same-sex couples may exercise the fundamental right to marry” in 2015, Michael McConnell and Jack Baker had been happily married for over 40 years.

Conclusion

Utilizing the tactics championed by the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, young Minnesotans took an active part in the Antiwar Movement. At the same time, members of other marginalized groups – American Indians, women, Mexican-Americans, members of the LGBTQ community – also stood up for their rights during the 1960s and 1970s. In some cases, local advocates – such as Denis Banks, Russell Means, Clyde Bellecourt, and Jack Baker – became national leaders.

The Minnesota experience during these turbulent decades also reflects the pressures and conflicts within each of these movements. Groups and individuals did not always agree on the best course of action, even when their goals were similar. Disagreements between more established, conservative activists and younger, more impatient activists can been seen in almost all of these movements. Additionally, mainstream perceptions of the uniquely Minnesotan power movements were tainted by what was going on nationally and in some cases gave inaccurate views of local activism.

The Antiwar Protest Movement impacted our country’s foreign policy and played a part in American de-escalation in Southeast Asia. The efforts of other social movements shared many of the outcomes with the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements – they realized very real and concrete achievements, but only just begun the struggle for complete equality.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Davis, Julie L. Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Holmquist, June Drenning, ed. They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s Ethnic Groups. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society, 1981.

Kenney, Dave and Thomas Saylor. Minnesota in the 70s. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2013.

Kroll, Becky Swanson. “Rhetoric and Organizing the Twin Cities’ Women’s Movement.” Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, 1981. Microform

Lehmberg, Sanford and Ann M. Pflaum. The University of Minnesota 1945-2000. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Nathanson, Iric. Minneapolis in the Twentieth Century: The Growth of an American City. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010.

Valdés, Dionicio Nodin, Barrios Norteños: St. Paul and Midwestern Mexican Communities in the Twentieth Century. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000.

Valdés, Dionicio Nodin, Mexicans in Minnesota. The People of Minnesota Series. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005.

Roethke, Leigh. Latino Minnesota. Afton, Minn.: Afton Historical Society Press, 2007.

Treuer, Anton Steven. Ojibwe In Minnesota. People of Minnesota Series. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010.

Van Cleve, Stewart. Land of 10,000 Loves: A History of Queer Minnesota. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Wittstock, Laura Waterman. We Are Still Here: A Photographic History of the American Indian Movement. Saint Paul, Minn.: Borealis Books, 2013.

Since the 1970s scholars have been using the term “Identity Politics” to denote groups that form around a shared identity, fight discrimination and advocate for fair treatment. In this chapter we will discuss several of these groups’ experiences in Minnesota from the mid 1940s to the 1970s including: African Americans, American Indians, Mexican American, women, and gays and lesbians.

Around midnight on July 10, 1970, four teams of two or three people each broke into Selective Service offices in Little Falls, Alexandria, Winona, and Wabasha, intending to destroy as many military draft files as possible—acts of protest against the war in Vietnam. They mostly failed. Eight of them were arrested and charged with federal crimes. They became known as the Minnesota Eight.

Paul Nelson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/minnesota-eight

The American Indian Movement (AIM), founded by grassroots activists in Minneapolis in 1968, first sought to improve conditions for recently urbanized Native Americans. It grew into an international movement whose goals included the full restoration of tribal sovereignty and treaty rights. Through a long campaign of “confrontation politics,” AIM is often credited with restoring hope to Native peoples.

John Lurie, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/american-indian-movement-aim

Formed in August of 1968, the American Indian Movement Patrol (AIM Patrol) was a citizens’ patrol created in response to police brutality against Native Americans in Minneapolis. Patrollers observed officers’ interactions with Native people and offered mediators that community members could call on for help. As of 2016, a similar but separate group operates under the same name.

Brianna Wilson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/aim-patrol-minneapolis

In 1970, the American Indian Movement (AIM) declared its intention to open a school for Native youth living in Minneapolis. AIM had identified the urgent need for Indigenous children to be educated within their own communities. Two years later, Heart of the Earth Survival School opened its doors, providing hope to Native families whose children had endured the racial abuse prevalent in the Minneapolis public schools.

John Lurie, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/heart-earth-survival-school

We need not give another recitation of past complaints nor engage in redundant dialogue of discontent. Our conditions and their cause for being should perhaps be best known by those who have written the record of America's action against Indian people. In 1832, Black Hawk correctly observed: You know the cause of our making war. It is known to all white men. They ought to be ashamed of it.

The government of the United States knows the reasons for our going to its capital city. Unfortunately, they don't know how to greet us. We go because America has been only too ready to express shame, and suffer none from the expression - while remaining wholly unwilling to change to allow life for Indian people.

We seek a new American majority - a majority that is not content merely to confirm itself by superiority in numbers, but which by conscience is committed toward prevailing upon the public will in ceasing wrongs and in doing right. For our part, in words and deeds of coming days, we propose to produce a rational, reasoned manifesto for construction of an Indian future in America. If America has maintained faith with its original spirit, or may recognize it now, we should not be denied.

Press Statement issued: October 31, 1972

When migrant workers from Mexico began to look for homes in Minnesota in the mid-twentieth century, many joined a growing enclave in Westside St. Paul. In spite of challenges, they sought opportunities to create a strong community and build a brighter future. They saw the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s as a means to that end.

Shirley Saldivar, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/chicano-movement-westside-st-paul

Throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, migrant workers, mainly from Mexico, have played a vital role in Minnesota’s economy, often working in low-wage farming and food-processing industries.

Jessica Lopez Lyman, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/migrant-workers

Since the early 1900s, Latinos have been a productive and essential part of Minnesota. Most of the earliest Minnesotanos were migrant farm workers from Mexico or Texas and faced obstacles to first-class citizenship that are still being addressed. They overcame the instability associated with migratory work by establishing stable communities in the cities and towns of Minnesota. Latinos faced, and still face, discrimination—both racial and the kinds common to all immigrants and migrants.

Jeff kolnnick, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/minnesotanos-latino-journeys-minnesota