5 Fur Traders: Economic and Cultural Exchanges

From the earliest stages of European exploration onward, the quest for imperial wealth and power drove competition in North America. Spain, France, Great Britain, and, to a lesser extent, Denmark and Sweden all rushed to found colonies, claim territory, and convert abundant resources into economic power. Spain, having sponsored Columbus, established an early presence in the Caribbean, which quickly expanded to create vast wealth through the cultivation of sugar and the mining of precious metals. Unable to dislodge Spain from the Caribbean basin, France looked to Canada to establish its foothold. The northeastern coast of North America did not support large-scale agriculture, nor did it yield vast deposits of precious metals. It was, however, teaming with fish and fur-bearing animals, and it was on these resources that the French focused their colonial efforts.

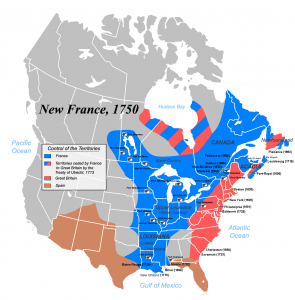

Although Great Britain, Denmark, and Sweden established colonies further south along the Atlantic seaboard and traded goods for furs with American Indian nations, from the early 1500s to the middle of the 1700s, the French, under the auspices of its colony New France, claimed the territory and controlled trade in around the Great Lakes and into the interior of what is today south-central Canada and the upper reaches of the American middle west.

From the establishment of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670, through its conquest of New France a century later, Great Britain ultimately proved successful in dislodging the fur trade from French control. By the 1790s, Britain’s North West Company had established its inland headquarters at Grand Portage in what is now the northeastern-most corner of Minnesota. Through Grand Portage, the North West Company connected Montreal with over 120 fur trading posts west of Lake Superior – it was a massive enterprise that connected Minnesota to the rest of the world. The arrival of the United States in 1783 and its expansion in 1803 ushered in a new and final phase of the trade administered through the American Fur Company’s headquarters near Fort Snelling in southeastern Minnesota. By the 1850s, the fur trade had ended in Minnesota as changing fashions in Europe, depletion of game, and the American hunger for land all combined to undermine an international business that operated for hundreds of years.

New France

Section Highlights

- The fur trade was based on cooperation between American Indians and Europeans – each group received benefits from the trade.

- France controlled the Great Lakes fur trade from the early 1600s until the 1760s.

- France adopted existing trade and diplomacy practices and learned the customs and languages of their American Indian trading partners.

- French traders intermarried with American Indian communities.

- Britain chartered the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670 to challenge the French dominance in the Great Lakes fur trade.

The fur trade depended on a cooperative working relationship between American Indians and Europeans. Both sides got something from the arrangement that they couldn’t get without close cooperation with the other. The Europeans received fur-bearing animal pelts in high demand, which they used to make coats and hats. Indigenous communities received European-manufactured goods such as tools, kettles, knives, needles, beads, fabric, dyes, guns, ammunition, etc. These trade goods made their lives easier. As the trade expanded from the coastline inland, the French established trading outposts at Quebec in 1608 and Montreal in 1642. This expansion coincided with two important developments. First, the Ojibwe were in the midst of their migration into the Great Lakes region, which allowed them to become the essential link in connecting French traders with people further west, including the Dakota living in what would become Minnesota. Second, the beaver hat became extremely popular in Europe. The underfur of the beaver was soft, resisted rain, and was easily manufactured into felt. It was perfect for making a variety of hats, which were in fashion in Europe. Having depleted the beaver populations in Europe, the French and others looked to America to supply the coveted furs.

The French controlled the fur trade through the Great Lakes and into the middle of the North American continent from its origin through the middle of the 18th century. In doing so, they adopted the customs of diplomacy and trade already existing between indigenous people for generations. French traders and voyageurs lived among indigenous communities, adopted their culture, learned their languages, and often married indigenous women. Not only did these marriages tie traders to indigenous communities economically, but they also resulted in large numbers of children of mixed ethnicity who later served as a bridge between the two cultures as they became more connected and dependent on each other.

While French traders went into the interior to live in and trade with indigenous communities, the British initially took a different approach in their attempt to challenge the French dominance in the upper Great Lakes. In 1670, King Charles II granted a charter to the Hudson’s Bay Company to trade throughout the Hudson’s Bay drainage area, then still technically part of New France. Rather than sending traders into the interior as the French had, the British established posts around the bay and waited for indigenous hunters to bring their furs to them. Regardless of Britain’s less-effective approach to trade, imperial warfare wrestled political control of the region away from France to Great Britain. While the French lost control of the territory surrounding the Hudson Bay in 1713 and the entirety of New France in 1760, many of the French Voyageurs continued to work in the fur trade, now under British control. Although the Hudson’s Bay Company continued relying on larger trading posts, other British fur trading concerns adopted an approach that mirrored the French tactic that sent their traders into the interior. With many French Canadians continuing to supply the labor for the British-run fur trade, French language and collaborative customs endured under British administration of the trade, which lasted from 1763 into the early 19th century.

Grand Portage – the Voyageur’s Highway

Section Highlights

- Grand Portage in the northeastern-most corner of present-day Minnesota became an important inland hub of the British fur trade.

- During the early 1780s, smallpox devastated Ojibwe populations in northern Minnesota.

- Montreal traders founded the North West Company in the early 1780s.

- The North West Company established its inland headquarters at Grand Portage in the mid-1780s, where it connected Montreal to some 120 fur trading posts west of Lake Superior.

- In 1802, the North West Company moved its operations north into British territory to avoid regulation and conflicts with the new United States.

Although the French-Canadian voyageurs continued to play their instrumental role in the trade, the British takeover did result in significant changes. Unlike the French, who attempted to control the fur trade through the government-sanctioned New France Company, the British opened the trade up to competition. By the mid-1760s, virtually anyone who could afford a license could legally engage in trade throughout the Lake Superior region. While the lack of oversight initially provided the Ojibwe, Cree, and Assiniboine more bargaining power, it also created a chaotic and violent atmosphere of ruthless competition among British traders carried out in a region free of any law enforcement. Massive amounts of alcohol, coveted by indigenous populations, French-Canadian voyageurs, and British traders alike, saturated the trade and made the situation even more dire.

Around this same time, the Grand Portage, located on the western edge of Lake Superior in what is today the northeastern-most corner of Minnesota, replaced Fort Michilimackinac as Britain’s western-most trading outpost in the Great Lakes region. The local Ojibwe people knew the portage as the Great Carrying Place because it bypassed a treacherous eight-and-a-half-mile stretch of the Pigeon River that connected Lake Superior to the vast interior west of the lake. Europeans soon took to calling the portage “the voyageur’s highway.” By the late 1770s, nearly 40,000 pounds of goods and furs passed over the portage each season, and as many as 500 people came to the area to participate in the trade. The lack of regulation and absence of any governing authority, however, made the Grand Portage a dangerous and scary place. One trader described it as “a pent-up hornet’s nest of conflicting factions in rival forts.” Another lamented “the traders [were] in a state of extreme hostility, each pursuing his own interests in such a manner as might most injure his neighbor.”[1]

As the Grand Portage was emerging as the crucial junction point of the chaotic trade west of Lake Superior, the British colonies along the Atlantic coast revolted against Great Britain and won their independence in a war that raged from 1775 to 1783. While no battles were fought in what would become Minnesota, the war did result in two critical developments that impacted the region. First, smallpox devastated colonial armies and spilled over through trade networks to decimate the Ojibwe and, to a lesser extent, the Dakota people living in Minnesota. Ojibwe people at Grand Portage, Leech Lake, and Rainy Lake were hit particularly hard by the pandemic in 1782 and 1783. Second, trade moving from Fort Michilimackinac, down the Wisconsin River, up the Mississippi River to the Dakota was disrupted. This interruption made the trade moving through Grand Portage even more important.

Two years after the war concluded and the new United States of America claimed lands east of the Mississippi River, a group of British merchants from Montreal and prominent fur traders operating out of Grand Portage combined to form the North West Company. The company quickly created a monopoly and pushed out most smaller companies and independent traders. As the North West Company consolidated power, it built a trading outpost on the Superior side of the Grand Portage that grew to include some 16 structures surrounded by palisades. During the 1790s, the North West Company’s operations at the Grand Portage reached its peak, and the company bypassed its rival, Hudson’s Bay Company, in size, reach, and volume. The depot became the transshipment point for trading goods arriving from Montreal and furs flowing in from over 100 posts throughout the interior west of the Great Lakes.

But Grand Portage’s trading peak proved short-lived. Fears of US government intervention convinced the North West Company to move its operations north into British territory in 1803. The following year, it enveloped the XY Company (a smaller rival formed in 1798) before merging with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821.

The Voyageurs

The voyageurs were the workmen of the fur trade. They paddled limitless miles in canoes, carried goods and furs across countless portages, and provided all the labor required during the fur trade. Mostly French Canadian or Metis (a person of mixed indigenous and European heritage), the voyageurs left behind a legacy of the jovial workman – they dressed colorfully and sang to keep the time and stave off boredom as they paddled. Many, however, found themselves stuck in disadvantageous contracts that left them in debt to the company and therefore stuck in a hard life of unrelenting labor.

There were two distinct categories of voyageurs in the trade west of Lake Superior.

North Men:

The North Men were voyageurs who spent the winters in the interior supplying the labor for the posts. Their responsibilities included transporting goods into the post in the fall and furs out of the post in the spring. During the winter, they provided the labor required to establish and operate the post. In the trade west of Lake Superior, voyageurs who spent their first winter in the interior were recognized with a plume to signify the first time they crossed the continental divide west of the lake. Other names for this group include Nor’ Westers and Winterers.

Montreal Men:

The Montreal Men transported trade goods from Montreal to Grand Portage in the spring and furs from Grand Portage to Montreal in the fall. They paddle large Montreal canoes capable of transporting over a ton of cargo and requiring ten to 16 men to power. Often, Montreal Men paddled fourteen hours a day for up to two months in their runs between Montreal and Grand Portage. In addition to transporting goods in canoes through the lakes, their contracts typically required that they take a certain number of 90-pound bundles across the portage as well. Other names for this group include Greenhorns and Pork Eaters.

Rendezvous

Section Highlights

- By the 1790s, the North West fur trade administered through the Grand Portage became a massive business that brought some 1,200 people together in a yearly cycle.

- The annual summer rendezvous held at Grand Portage became the high point of the Lake Superior fur trade.

By the 1790s, the Grand Portage had become the focal point of the seasonal trading cycle administered by the North West Company west of Lake Superior. In doing so, it not only filled a vital economic role, but it also served as a meeting point for cultural exchanges between the Ojibwe, French Canadian voyageurs, and British traders – many of Scottish descent. At its height, the fur trade seasonal cycle operating out of Grand Portage looked like this:

Fall

In the late summer or early fall, greenhorn voyageurs left Grand Portage in canoes loaded with furs collected from the interior the preceding winter. The massive Montreal Canoes each carried a ton of furs and had to be powered by up to 16 men. They paddled daily for six or more weeks through the Great Lakes and up the St Lawrence Seaway before arriving in Montreal, where merchants exported the pelts to Europe.

A second group of voyageurs – known as Nor’Westers or winterers left for the interior laden with trade goods brought from Europe and Asia through Montreal the previous summer. Wintering Partners, clerks, and voyageurs returned to interior posts located throughout Minnesota and points beyond.

Winter

Upon arrival and establishment of their fur posts, traders provided goods to Ojibwe trappers on credit. Throughout the winter, Ojibwe men hunted and trapped fur-bearing animals, while Ojibwe women prepared pelts and conducted trade negotiations at fur posts. Wintering Partners supervised trading posts, while clerks kept accounts. Ojibwe families provided not only pelts but also food as part of the trade.

Spring

Partners, clerks, and voyageurs concluded trading, finalized accounts for the season, packaged furs, and began the journey back to Grand Portage.

In Montreal, merchants hired voyageurs to paddle canoes filled with trade goods headed to the Grand Portage.

Summer

During the summer, fur traders from the interior arrived at Grand Portage with the furs collected throughout the winter. Voyageurs and clerks received their salaries, much of which was spent on goods, food, and drink purchased from North West Company stores within the post. Meanwhile, merchants from Montreal traveled to the Grand Portage to hold annual business meetings with the wintering partners arriving from the interior. Ojibwe families also traveled to and spent time trading at Grand Portage during the summer. All this activity was the high point of the cycle and referred to as the rendezvous. At its height, perhaps upwards of 1,000 people representing all the different players in the fur trade participated in the annual rendezvous at Grand Portage.

The Grand Portage National Monument

The North West Depot at Grand Portage

text here

- North West Company flag

- North West Company re-enactor.

- Voyageur re-enactors

- Re-enactment of Montreal Canoes arriving at the Grand Portage

- Re-enactor portraying a voyageur

- Great Hall and Kitchen at the North West depot at Grand Portage

- Trade goods stock piled at Grand Portage

- The Grand Portage National Monument. January 2022.

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book. Photograph by Kurt Kortenhof July, 2004-2022.

The American Fur Company

Section Highlights

- The American Fur Company, founded in 1808, came to dominate the fur trade in Minnesota after the North West Company moved its headquarters out of Grand Portage.

- The geographical focus of the fur trade moved from Grand Portage to Fort Snelling, which the U.S. Military had built in the early 1820s.

- The American period of the fur trade was short-lived as fashion tastes in Europe changed, game became harder to harvest, and an American quest to acquire ownership of land all combined to undermine the trade.

Despite the relocation of its headquarters, North West interior posts remained operating in Minnesota and throughout the Lake Superior region well into the second decade of the 19th century. Regardless, the American Fur Company, founded in 1808, soon came to dominate the trade in Minnesota. The conclusion of the War of 1812, after which the British agreed to do a better job of respecting American territorial sovereignty, and President Monroe’s 1817 declaration that closed all trading on US soil to non-U.S. citizens further solidified the American Fur Company’s position. In many cases, especially for those trading with the Dakota in southern Minnesota, British traders who were often of French-Canadian ancestry simply became American citizens and continued their work. In time, many came to work for the American Fur Company.

From their headquarters in southeastern Minnesota near the meeting point of the Mississippi and the Minnesota Rivers, the American Fur Company had established a monopoly on most trade in Minnesota by the early 1820s. Several years earlier, the US military began construction on a post that became Fort Snelling to help, among other things, administer the fur trade. A profitable business in trading furs for the American company proved to be temporary, however, as changing fashions in Europe, depleted resources in Minnesota, and an encroaching nation hungry for land all combined to undercut the centuries-old trade.

The American Fur Company at Mendota

The Minnesota Historical Society’s Sibley Historic Site in Mendota depicts, among other things, the fur trade under the American Fur Company.

- Henry Hasting Sibley Historic House

- American Fur Company trade goods

- American Fur Company pelts

- American Fur Company fur press

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book. Photographs by Kurt Kortenhof July 2004.

Cultural Impacts

Section Highlights

- The fur trade facilitated a meeting and, to a certain extent, the merging of cultures.

- Ojibwe and Dakota Women played a leading role in these cultural connections as they entered into marriages with European voyageurs and traders.

- The children of mixed European and indigenous heritage will go on to play a leading role as the two cultures become increasingly connected in the new United States.

The fur trade proved hugely successful in bringing trade goods to the Ojibwe and Dakota, which made their lives easier while providing sought-after furs for European markets. In addition, and perhaps more importantly, were the cultural ramifications that came with that trade. The fur trade connected Minnesota to the world not only economically, but culturally as well. It brought together merchants, partners, and clerks from Scotland and England, French Canadian voyageurs, and Ojibwe and Dakota people. In the process of exchanging goods, these cultures merged in the lands west of Lake Superior. Not only did indigenous peoples adopt European goods, but Europeans adopted the foods, dress, and technologies of the Ojibwe in the north and the Dakota further south.

Ojibwe and Dakota women stood at the very center of this cultural connection. From an economic perspective, they played a crucial role in preparing animal pelts for European traders and often took the lead in trade negotiations at the post level. Far more importantly, however, were marital unions that brought French Canadian voyageurs, British and Scottish clerks and partners together with Ojibwe and Dakota women. These marriages certainly facilitated economic relationships, but more importantly, they served to connect and merge cultures. Many of the children born of these unions grew up connected to both cultural traditions and proved invaluable going forward. With language skills and a multicultural understanding, these children and their children went on to help navigate a future that brought both the indigenous and European cultures closer together in the new United States.

Conclusion

North of Minnesota, in 1821, the Hudson’s Bay Company absorbed the North West Company as the fur trade declined. The following decade, silk replaced fur as the most sought-after material from which to fashion hats. The resulting decline in demand, combined with increased difficulty in harvesting depleted populations of fur-bearing animals, undermined the very foundation of the trade. Debts at all levels north and south of the international border went unpaid, and the international fur trade that dominated the interior of North America and connected it to the rest of the world for hundreds of years slowly faltered.

Throughout its history, the fur trade west of Lake Superior drove not only the economics of the area but also served as a conduit for cultural exchanges between Europeans, the Ojibwe, the Dakota, and other indigenous nations. The trade changed all groups involved and left of legacy through children born of European-indigenous unions and the unique culture created during the centuries-long collaboration. Just as importantly, however, the fur trade left Ojibwe and Dakota people dependent on trade goods, troubled by the introduction of alcohol, and saddled with unpayable debt. In the coming decades, the United States government used these realities to push land-cession treaties on indigenous nations in Minnesota and elsewhere.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Blegen, Theodore. Songs of the Voyageurs. St Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1966.

Ehrenhalt, Lizzie. “Grand Portage (Gichi Onigamiing).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/place/grand-portage-gichi-onigamiing (accessed December 30, 2021).

Lurie, Jon. “Fur Trade in Minnesota.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/fur-trade-minnesota (accessed December 24, 2021).

“The Fur Trade,” Historic Fort Snelling. Minnesota Historical Society. https://www.mnhs.org/fortsnelling/learn/fur-trade (accessed December 24, 2021).

White, Bruce M. “Give Us A Little Milk: The Social and Cultural Meanings of Gift Giving in the Lake Superior Fur Trade.” Minnesota History Summer, 1982. pp. 62-71.

Wingerd, Mary Lethert. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

- Wingerd, Mary Lethert Wingerd, North Country: The Making of Minnesota. (Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 59. ↵

Grand Portage (Gichi Onigamiing) is both a historic seasonal migration route and the traditional site of an Ojibwe summer village on the northwestern shore of Lake Superior. In the 1700s, after voyageurs began to use it to carry canoes from Lake Superior to the Pigeon River, it became one of the most profitable fur trading sites in the region and a headquarters for the North West Fur Company.

Lizzie Ehrenhault, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/grand-portage-gichi-onigamiing

The U.S. Army built Fort Snelling between 1820 and 1825 to protect American interests in the fur trade. It tasked the fort’s troops with deterring advances by the British in Canada, enforcing boundaries between the region’s Native American nations, and preventing Euro-American immigrants from intruding on Native American land. In these early years and until its temporary closure in 1858, Fort Snelling was a place where diverse people interacted and shaped the future state of Minnesota.

Matthew Cassady and Peter DeCarlo, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/fort-snelling-expansionist-era-1819-1858