14 Searching for Bright Sunshine: The Civil Rights and Black Power Movements – 1945-1975

The two decades that spanned the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s were turbulent times in American history. Gaining traction in the late 1940s, the Civil Rights Movement realized remarkable gains by the middle of the 1960s.

Several Minnesotans, including Hubert Humphrey and Roy Wilkins, played prominent national roles in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Others, including Nellie Stone Johnson and Matthew Little, led Civil Rights advocates locally in Minnesota. Meanwhile, private colleges and state-sponsored campuses all worked to increase enrollment of minority students and create a more inclusive curriculum. At the University of Minnesota, students played a leading role in expanding their opportunities. In K-12 education, the state’s largest and most diverse districts struggled against public opinion and urban demographics to remedy their segregated schools.

But despite significant accomplishments of the Civil Rights Movement, daily life for many African Americans continued to be defined by frustrating discrimination and a lack of opportunity. In response to the sluggish rate of change and rampant inequalities in the ghettos of the northern cities, a less accommodating Black Power Movement emerged. By the late 1960s, race-based violence and large-scale riots stunned large cities across the nation.

In Minneapolis, the Black Power Movement made definite connections to the larger national movement, but also maintained its own unique identity that made it less violent and more connected with the city’s existing power structures. Regardless, in the summers of 1966 and 1967, frustration boiled over and riots rocked and burned the city.

Both Civil Rights activists and those more connected with the Black Power Movement fought against generations of ingrained discrimination and rampant inequalities. While the movements fell short of their goals of total equality, advocates forced the state and country to make difficult and painful steps forward.

Attempting to Walk Forthrightly into the Bright Sunshine: Civil Rights and Expanding Educational Opportunities

Civil Rights activists achieved significant accomplishments during and shortly after World War II that set the stage for the momentum of the 1950s and 1960s. As the country’s entry into World War II loomed, a potentially embarrassing proposed march on Washington convinced President Franklin Roosevelt to desegregate the defense industry in 1941. Shortly after the war, growing pressure from activists and Cold War image concerns helped convince President Harry Truman to desegregate the Armed Forces and the Civil Service in 1948. Throughout the 1940s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) continued to push for the end of state-mandated segregation and the adoption of anti-lynching legislation on the national level. At the same time, the local affiliates of the Urban League worked in cities across the country to advocate for racial cooperation and improved training and job opportunities for African Americans.

Mayor Humphrey: Changing the Status Quo in Minneapolis and Beyond

The time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states’ rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.

-Hubert Humphrey

Section Highlights

- Minneapolis in the 1940s was a city of 500,000 with small minority populations.

- Hubert Humphrey served as Mayor of Minneapolis from 1945 to 1948.

- Humphrey worked with Civil Rights Activists such as Cecil Newman to combat discrimination.

- Humphrey went on to serve in the US Senate and as Vice President and became a strong advocate for Civil Rights at the national level.

By the mid-1940s, Minneapolis was a city of 500,000, including a Jewish population of 25,000 along with an African American population of just 5,000. Like many other northern cities, Minnesota’s largest city discriminated against its minority residents by preventing equal access to employment, housing, education, restaurants, and other public accommodations. In 1946, the city gained the dubious distinction of being labeled the “Anti-Semitic capital of the United States” by Carey McWilliams of The Nation magazine.

The efforts of Cecil E. Newman, president of the Minneapolis Urban League and editor of the Minneapolis Spokesman, on behalf of the African American community, along with Jewish community organizations fighting Anti-Semitism, found a powerful ally when 32-year-old Hubert H. Humphrey became the mayor of Minneapolis in 1945. After controversially advocating for “equal opportunities…regardless of race” during his mayoral campaign, Humphrey worked to address discrimination in Minneapolis. In early 1946, he collaborated with community organizations to create the Council on Human Relations that worked “to assure all citizens the opportunity for full and equal participation in the affairs of this community.” In addition to educational efforts, the council conducted a community self-survey in 1947. Data collected by 600 volunteers confirmed that rampant discrimination existed in housing, employment, public accommodations, and other aspects of community life. It also revealed segregationist attitudes of the city’s white community (for example, 63% of those surveyed objected to having an African American neighbor).

Fighting for Civil Rights in 1940s Minneapolis and St Paul

- Hubert Humphrey during his run for the Mayor of Minneapolis in 1943.

- Hubert Humphrey, Mayor of Minneapolis, 1946.

- Cecil Newman. Founder, editor and publisher of the “Minneapolis Spokesman” and the “St. Paul Recorder”

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

To challenge this reality, Humphrey, the Council on Human Relations, and other community organizations pushed the city council to enact the nation’s first enforceable Fair Employment Practices Ordinance (FEPO). It established a commission to review cases that violated the ordinance’s ban on discrimination in employment and hiring. While the commission reviewed few cases early on, the ordinance did change the status quo in Minneapolis and made employers and business owners question longstanding discriminatory practices.

In 1948, Humphrey was elected to the United States Senate and became a strong voice for minority rights on the national stage for the next three decades. He introduced himself to the national debate over civil rights at the 1948 Democratic National Convention when he famously told the convention and the nation:

My friends, to those who say that we are rushing this issue of civil rights, I say to them we are 172 years late. To those who say that this civil-rights program is an infringement on states’ rights, I say this: The time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states’ rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.

Hubert H Humphrey speaks at the 1948 Democratic National Convention in support of Civil Rights

Humphrey went on to have a long and effective political career not only as a US Senator from 1949 to 1964 and 1971 to 1978, but also as Vice President from 1965 to 1969 and as the Democratic presidential nominee in 1968. Among other achievements, Humphrey proved instrumental in the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act that outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, gender, or national origin in public places.

Local Activists, National Leaders, and Marching on Washington

Section Highlights

- Nellie Stone Johnson was an influential Civil Rights and labor leader in the Twin Cities.

- Roy Wilkins, who spent his childhood in Saint Paul and attended the University of Minnesota, led the NAACP from 1949 to 1977.

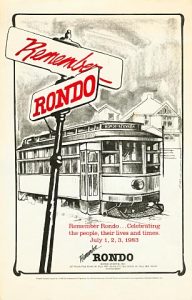

- The construction of Interstate 94 bisected Rondo, a Saint Paul African American community during the 1960s, displacing many of its residents.

- Local activists, including Matthew Little, organized Minnesota’s participation in the 1963 March on Washington.

- The success of the 1963 March on Washington helped lead to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Many Minnesotans played important roles in the Civil Rights Movement, both nationally and at the state and local levels. Nellie Stone Johnson, a labor and Civil Rights activist, became the first African American elected to a Minneapolis citywide office when she won a seat on the library board in 1945. She became an advisor to the incoming mayor and worked closely with Humphrey in creating the city’s F.E.P.O. Ten years later, she was again a strong voice in support of minority and workers’ rights in her advocacy of the Minnesota State Act for Fair Employment Practices, a statewide version of the Minneapolis ordinance, which became law in 1955.

Minnesota Civil Rights Leaders

- Nellie Stone Johnson (1905-2002) was a labor activist, a civil rights leader, and a business owner.

- Anna Arnold Hedgeman, politician and activist.

- Roy Wilkins, who led the NAACP from 1949 to 1977, grew up in St. Paul and graduated from the University of Minnesota.

- Whitney Young – President of the National Urban League – photograph taken during a meeting between Civil Rights leaders and President Johnson on January 18, 1964.

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

Also in 1955, Roy Wilkins, who spent his childhood in St. Paul and earned a sociology degree from the University of Minnesota in 1923, became the executive secretary of the NAACP. Having been acting executive secretary since 1949, Wilkins led the organization for the better part of 30 years before retiring in 1977. During his tenure, the NAACP played a leading role in realizing significant legal achievements, including the Brown v. Board of Education ruling that outlawed segregation in public schools in 1954, the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1964, and 1968, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Perhaps one of Wilkins’ most gratifying achievements was the role he played in the historic March on Washington in 1963. In June of that year, President John Kennedy had asked Congress for significant Civil Rights legislation that would outlaw segregation in public places, ensure voting rights, and end discrimination in publicly funded programs. An impressive coalition of Civil Rights groups quickly organized a massive march on the nation’s capital in support of the bill. As the head of the NAACP, Wilkins played a prominent role in planning and executing the effort. But he was not the only planner with ties to Minnesota. Whitney Young, the executive director of the Urban League, was also a graduate of the University of Minnesota, having earned a master’s degree in social work in 1947. While in the Twin Cities, he had first joined the Urban League as a volunteer in its Saint Paul affiliate. Additionally, Dr. Anna Arnold Hedgeman, the only woman on the planning team, grew up in Anoka, Minnesota. In 1922, she had become the first African American graduate of Hamline University in Saint Paul. She went on to have a prolific career as a Civil Rights leader, educator, and author.

Saint Paul’s Rondo Neighborhood

Even as Wilkins worked to advance opportunities and equality for African Americans at the national level, the predominantly African American Rondo neighborhood of Saint Paul, where he had spent much of his childhood, fell victim to another form of discrimination. By the 1930s, Rondo, which spanned from Lexington Ave. in the west to Rice Street in the east and University Avenue in the north to Marshall Avenue in the south, had emerged as the center of Saint Paul’s African American community. A mixture of middle-class and lower-income families created a tight-knit, vibrant community that was, in many ways, self-sufficient. In 1956, Congress passed the Federal Aid Highway Act, which provided funding to create the interstate highway system. Over community objections, Saint Paul urban planners chose to run Interstate 94 through the heart of the Rondo Neighborhood and in the process displaced 433 households, including 312 “non-white” homes, nearly all of which were African American. In 1968, when I-94 opened to traffic through Saint Paul, it did so only after dissecting Rondo. In the 1980s, a community organization formed to “bring back a sense of community, stability, and neighborhood values of the old Rondo community.” Today, the Rondo Day Festival is held annually as an attempt to share “the contributions of African Americans and the rich cultural history of the Rondo community.

The coalition’s efforts came together on August 28 when an integrated crowd of 250,000 people from all corners of the country assembled at the Lincoln Memorial to sing, listen to speeches, and show peaceful support for “jobs and freedom.” King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, broadcast live to millions of TV viewers, proved to be a highlight of the event and caught the attention of the nation.

The local effort to organize the Minnesota contingent for the march fell to a committee of local activists chaired by Matthew Little. The group scrounged together $6,000 to charter a plane from Minneapolis-Saint Paul Airport to Washington, D.C. Upon the group’s return, it organized the March on Washington Committee and successfully lobbied the Minnesota Congressional delegation to support the pending legislation. The following year, in no small part due to the march and Humphrey’s efforts in the Senate, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law. The following year, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act. Gathering together again 40 years later, some of Minnesota’s event participants recalled the collaboration, the hope embodied in the march, and the nearly constant refrain of “we shall overcome.”

North Star: Minnesota’s Black Pioneers, “Minnesotans March on Washington”

Expanding Opportunities in Higher Education

Section Highlights

- By the middle of the 1960s, colleges and universities across Minnesota and the nation attempted to increase their minority enrollment.

- The E-Quality Program at Moorhead State College is an example of efforts to increase minority enrollment.

- Students at the University of Minnesota played a central role in pushing for more equal treatment and creating an African American Studies program.

By the middle of the 1960s, predominantly white colleges and universities across the nation began recruitment and programs aimed at increasing the enrollment of African American students. In Minnesota, private four-year colleges led the way and achieved significant increases in minority student enrollment. In 1968, Carlton College in Northfield created an Ad Hoc Committee on Negro Affairs and an Office of Minority Affairs the following year. These efforts corresponded with a drive to recruit African American students on a “selective and national scale.” As a result, African American enrollment grew from 50 students in 1968 to 130 in 1974, an increase from 3% of the student body to 8%. Macalester College in St. Paul posted even more impressive numbers. In 1969, the college established an Expanded Educational Opportunities Program that helped increase African American student enrollment from 40 (2% of the student body) in 1968 to 170 (10% of the student body) in 1974. The state college system (with campuses at Mankato, Winona, St. Cloud, Marshall, Bemidji, and Moorhead) also posted increases in minority student populations. Enrollment of minority students at all state-sponsored campuses, including the Twin Cities Campus of the University of Minnesota, which had the largest minority population of any campus in the state, rose from 2.9% in 1972 to 3.7% in 1974.

Even regional campuses that served local communities with tiny African American populations attempted to expand opportunities for minority students. Moorhead State College in northwestern Minnesota, which serves the Fargo, North Dakota/Moorhead, Minnesota, regional area, provides one example. In 1970, the two cities combined had a total population of nearly 89,500 people, which included only 101 African-American residents. Even so, in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in April 1968, Moorhead State College implemented an E-Quality Program that brought 50 minority students to campus that fall (including 35 African American, eight American Indian, and seven Mexican-American students). The program included recruiting, financial aid, counseling, and educational programs for its participants and continued into the early 1970s. E-Quality brought approximately 120 African American students to campus and served as a catalyst for the creation of the Institute for Minority Group Studies. E-Quality Program participants played a leading role in exposing the larger campus community to Civil Rights issues, even as they struggled with discrimination and intolerance on campus and in the surrounding community.

At the Twin Cities Campus of the University of Minnesota, African American students themselves organized, forced change, and moved the university toward a more inclusive curriculum. In 1969, only 250 of the University’s 41,000 students were African American, and the University did not allow these students to live in the campus dormitories or join any of its social organizations. Further, the university offered no coursework relating to African American history or culture. In January 1969, about 60 student-members of the Afro-American Action Committee (AAAC), led by Rose Mary Freeman and Horace Huntley, took over Morrill Hall, a university administration building. They expelled the employees, barricaded the doors, and insisted that a list of demands they had previously delivered to University President Malcolm Moos be addressed. Increasingly hostile crowds gathered outside Morrill Hall, and the situation grew tense as students, local Civil Rights leaders, and administrators negotiated well into the night. The following day, negotiators reached a compromise that defused a potentially explosive situation. Out of the compromise came the Martin Luther King Program to advise and assist low-income students and an African American Studies Program, from which Rose Mary Freeman became a graduate a few years later.

The U and the Way

Excerpted from: Cornerstones: A History of North Minneapolis

Addressing Segregation in K-12 Public Schools

Section Highlights

- By the 1970s, housing patterns had created racially segregated schools across the nation and in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

- Minneapolis utilized busing in a controversial attempt to create racially balanced public schools.

By the early 1970s, housing patterns and urban school district policies had created racially unbalanced schools throughout the nation. Many districts, forced to address the disparities by Civil Rights advocates and actual or threatened legal action, turned to solutions that included busing students beyond neighborhood schools in attempts to balance enrollments. In Boston, Massachusetts, and Louisville, Kentucky, these efforts met with nationally publicized violent opposition.

In Minnesota, the two largest urban districts – Minneapolis and St. Paul – also faced racially unbalanced schools. The St. Paul Public School District established magnet schools with specific academic focuses to address the unbalance. By providing sought-after academic programs in predominantly African American schools, the district allowed families to take part in a voluntary approach to desegregation. In Minneapolis, where African American populations were larger and disparities more pronounced, the district adopted a proposed solution that included busing students beyond their neighborhood schools. The effort, while not leading to the violence witnessed in Boston, met with much opposition and only limited success.

Segregation in the Minneapolis public schools was most apparent in the district’s elementary schools. While minority students comprised under 15% of the district’s student population in the early 1970s, three elementary schools had minority populations of over 70%, while four other schools had six or fewer minority students. District measures to address the disparities proved half-hearted, and a vocal opposition movement emerged to oppose any efforts to utilize busing to address the inequalities. In early 1970, the Neighborhood School Committee collected 7,000 signatures in Minneapolis and St. Paul on a petition opposing busing. Nevertheless, that November, the Minneapolis School Board approved “human relations guidelines” that included a busing plan. But the five-hour meeting held at South High School drew an angry crowd of over 800 who verbally assaulted the board and convinced Superintendent John B. Davis that the “intensity” of the crowd and the “number of racist remarks showed a deep-seated hostility toward integration.”

During the first three months of 1971, the district held more than 100 meetings trying to address public concerns over a pilot busing program involving only two schools set to begin in the fall. Over intense opposition, the pilot program commenced with no major issues. Despite the unfolding bussing plan, the school board’s actions fell far short of state expectations. While the district developed a more comprehensive plan to desegregate, a court case, Booker v. Special School District No. 1, began in April 1972. Judge Earl Larson ordered that the district pursue its comprehensive plan, placed the district under judicial supervision, and mandated that no school have a minority population that exceeded 42%. While busing did begin to address the disparities and resulted in relatively few issues in the schools, the district continually fell far short of the court-mandated threshold. By 1976, 13 schools had student minority populations exceeding 42%.

Ultimately, the district’s desegregation solution (of which busing was only one component) could not keep up with the city’s changing demographics. Between 1971 and 1976, the district’s white student population fell by some 15,000, or 27%, as families moved to the suburbs in a phenomenon often called white flight. After the district launched several unsuccessful court challenges, Larson raised the threshold to 48% minority student populations in 1978 and then to 50% in 1981. By 1983, the district was able to maintain the 50% proportion and was released from court oversight. In the end, the district’s attempt to desegregate its schools met with limited success and played a role in pushing the segregated-schools problem beyond the district’s borders. Between 1963 and 1983, for example, the minority student enrollment in Minneapolis schools rose from 6% to 35%. By 1989, minority students accounted for 50% of the total student population. Schools were becoming segregated by housing patterns that congregated minority families in Minneapolis and non-minority families in its surrounding suburbs. By the 1980s, it had become clear that effective desegregation policies would have to span the entire metropolitan area to have any real impact, but the political will and infrastructure for such an effort did not exist.

Minneapolis Public Schools Desegregation – KSTP News, March 14, 1972

The Black Power Movement

In the middle of the 1960s, even as the non-violent Civil Rights Movement scored some of its more important legal victories, a growing faction of younger activists began to grow impatient with the plodding pace of limited change. The Black Power Movement that emerged largely from the urban ghettos of large American cities was far less accommodated and not committed to non-violence. Driven by frustration bred by ever-present discrimination and lack of opportunity, Black Power brought race-based violence to cities across the country, including Minneapolis.

Long Hot Summers in Minnesota

Section Highlights

- Like other major urban areas, Minneapolis experienced race-based riots during 1966 and 1967.

- Disturbances and riots centered on Plymouth Avenue in the summers of 1966 and 1967.

- The Way, a community-based organization in North Minneapolis, aligned itself with the broader Black Power movement, but maintained unique ties to the existing power structure of the city.

- In the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Minnesotans marched peacefully, and Minneapolis remained quiet.

In the wake of the 1966 attempted assassination of James Meredith, who was shot while walking across Mississippi in what he had called the March Against Fear, Roy Wilkins held fast to his belief that pursuing legal challenges and peaceful protests was the most promising route to achieve integration and equality. Stokely Carmichael disagreed; he began advocating a more militant approach and coined the phrase “Black Power.” While Wilkins and others disapproved of the more militant wing of the movement, the nation’s urban centers erupted in violent conflicts. During the Long Hot Summers between 1964 and 1968, hundreds of riots destabilized the nation’s larger cities. Beginning in the Watts area of Los Angeles in 1965, when a 13-day riot left 34 dead, 900 injured, and 4,000 in jail, these summer clashes spread across the nation. In 1967, Milwaukee, Dayton, San Francisco, and Cleveland were rocked by urban uprisings, while in Newark, 25 died during a five-day riot. Just a week later, tanks and troops were needed to quell violence in Detroit that left 34 people dead and 7,000 arrested.

Minneapolis also saw race-based urban violence on its North Side in the middle of the 1960s. One of the few places where the city’s discriminatory housing policies allowed Jewish and African American residents to live, the Near North Side developed into a multicultural community during the first half of the 20th century. After World War II, however, many of the Jewish middle-class residents and business owners began to take advantage of expanding opportunities and move out of North Minneapolis to the nearby suburb of St. Louis Park.

Minneapolis denied these same opportunities to its African American residents, whose tiny population began to expand during the 1950s and early 1960s. These trends resulted in the development of an increasingly poverty-stricken African American enclave on the Near North Side that faced discrimination in housing, educational opportunities, and employment from the surrounding city.

In early August 1966, dozens of African American youths lashed out at what they associated with the source of discrimination – white-owned businesses along Plymouth Avenue. Shattering storefront windows, looting, throwing rocks and firing guns into the air, the would-be rioters quickly dispersed when 30 police officers equipped with riot gear responded. Civil Rights activist, politician, and Near North Side resident, W. Harry Davis recalled:

I was disheartened that most of the stores that were vandalized on Plymouth Avenue were Jewish-owned. Jews and blacks had lived in cooperative proximity in my old neighborhood for more than half a century, but the passions and events of the 1960s were pulling them apart. The end of housing discrimination opened the rest of the city and its suburbs to the North Siders, both black and Jewish, with the means to move out. Within a span of a few years, shop owners went from being neighbors to semistrangers who lived in comfort someplace else. As the Jewish population assimilated into the larger society, they increasingly became just white folks in the eyes of young black people. For a small but increasingly frustrated and impatient share of the black population that remained on the North Side, the shops became a near-at-hand symbol of what white people had and they did not. The shops were targets of rage, not because they were owned by Jews but because they were not owned by blacks.

The morning after the disturbance, Minneapolis Mayor Arthur Naftalin brought Civil Rights leaders together with business leaders and government officials (including Governor Karl Rolvaag) at City Hall in an attempt to address the underlying cause of the unrest. The governor, mayor, and Civil Rights leaders agreed to meet with the leaders of the discontented youth at Oak Park and heard from them that what they wanted, above all else, were employment opportunities. Business leaders promised jobs, advertised at a job fair held at City Hall, but they proved short-lived and had little impact.

Plymouth Avenue Disturbances, June 1966

In the aftermath of the 1966 disturbances, community organizers founded The Way on the Near North Side. The Way aligned itself with the national Black Power movement in that it advocated self-reliance, more militant protest, and African American pride, but it was also unique in its support from Mayor Naftalin, its funding received from the white business community, and its willingness to coordinate with the existing city power structure. Regardless of these notable distinctions, many middle-class white and black Minneapolitans opposed the organization as they saw it simply as a local affiliate of the Black Power movement. Even African American church leaders and established local Civil Rights leaders such as Cecil Newman and Harry Davis distanced themselves from The Way, as they feared it could lead to a reversal of many of the gains local activists had achieved.

Neither the mayor’s inadequate jobs initiative nor the efforts of The Way were able to avoid more violent confrontations along Plymouth Avenue the following summer. On the night of July 19th, 1967, frustrations boiled over again after the annual Aquatennial Torchlight Parade. Police tactics in responding to a fight as the parade concluded sparked a night of angry confrontation in North Minneapolis. Firefighters sent to put out fires set by demonstrators along the avenue were pelted with rocks and bricks before riot police arrived to protect them.

While volunteer staff members from The Way filtered through the crowd attempting to defuse the tension, community leaders urged Naftalin to avoid forcibly clearing the street. He followed their advice and did not order mass arrests but rather deployed the police to protect the firefighters as they battled the numerous fires then burning up and down the avenue. The decision resulted in few arrests and no deaths, but angered many in the police force who felt a stronger response was necessary to avoid further destruction of property. The following night brought additional but less intense unrest and numerous arson fires that began after news that a white bar owner had shot an African American patron made its way through North Minneapolis. As the weekend approached, Governor Harold Levander dispatched 600 National Guard troops to Minneapolis at Naftalin’s request, and order was restored in Minneapolis.

Racial Unrest in North Minneapolis – Plymouth Avenue, 1967

- National Guard in Minneapolis

- National Guard in Minneapolis

- Aftermath of race riots

- Aftermath of race riots

- Aftermath of race riots

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

The following spring, on April 4, 1968, news of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in Memphis, Tennessee, resulted in riots in over 100 cities across the nation. Federal and state governments responded by sending over 50,000 troops to quell the violence. In the end, 39 people lost their lives in the unrest – 34 of the fatalities were African American. Minneapolis, unlike most major cities, remained quiet in the wake of King’s murder. Rather than rioting, some 7,000 Minneapolitans took to the streets to march in a somber demonstration. Across the state, perhaps as many as 15,000 people took part in peaceful marches. Reflecting the city and state demographics, the Minneapolis Spokesman estimated that perhaps three-quarters of the marchers in the city and across the state were white.

While the disturbances in Minneapolis paled in comparison to the riots that rocked other major cities in the late 1960s, they did highlight the growing frustration of its African American community. Naftalin’s willingness to support African American empowerment efforts, as illustrated by his support of The Way, his inclusion of local African American Civil Rights Activists in decision making, and his restraint in dealing with the urban unrest, played a part in de-escalating tense situations. Regardless, his approach also drew harsh criticism for being too restrained. When Naftalin decided not to seek reelection in 1969, Charles Stenvig, a police detective and head of the Minneapolis Police Federation who had been especially critical of the mayor’s handling of the urban unrest in 1967, replaced him. Stenvig ran on a “law and order” platform that mirrored conservative political trends across the nation and easily defeated Harry Davis, the first African American to run for the city’s mayoral office.

Plymouth Avenue: The First Minneapolis Street With A History of Racial Conflict

Conclusion

Despite the significant Civil Rights achievements realized by the mid-1960s and well-intentioned efforts to address ongoing discrimination and inequalities that caused urban unrest in Minneapolis in 1966 and 1967, the struggle for real equality had just begun. That Minneapolis elected a “Law-and-Order” candidate as its mayor and that his African-American opponent, Harry Davis, received death threats and required police protection illustrates how difficult it is to undo generations of discrimination and inequality.

Clearly, in Minnesota and across the nation, activists did not achieve all that they set out to do in the 1960s and 1970s. They did, however, score impressive successes and brought local and national attention to the disparities within our society. They could not be ignored and, therefore, began a conversation that has expanded to include other marginalized groups – including indigenous people, Mexican Americans, Women, and same-sex couples – that continues to evolve today.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Davis, W. Harry. Overcoming: The Autobiography of W. Harry Davis. Afton, Minn.: Afton Historical Society Press, 2002.

Cooper, Arnold. “Beyond the Threshold: Black Students at Moorhead State College, 1968-1972.” Minnesota History, Spring 1988.

Holmquist, June Drenning ed. They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s Ethnic Groups. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society, 1981.

Kenney, Dave and Thomas Saylor. Minnesota in the 70s. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2013.

Lehmberg, Sanford and Ann M. Pflaum. The University of Minnesota 1945-2000. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Maddox, Camille Venne. “The Way Opportunities Unlimited, Inc.”: A Movement for Black Equality in Minneapolis, 1966-1970.” BA Honors Thesis, Emory University, Department of African American Studies, 2013.

Nathanson, Iric. Minneapolis in the Twentieth Century: The Growth of an American City. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010.

Rosh, B. Joseph. “Black Empowerment in 1960s Minneapolis: Promise, Politics and the Impact of the National Urban Narrative.” MA Thesis. Moorhead State University, 2013.

Taylor, David Vassar. African Americans in Minnesota. The People of Minnesota Series. Saint Paul, Minn: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002.

Hubert H. Humphrey, a giant of Minnesota politics, was one of the most influential liberal leaders of the twentieth century. His political rise was meteoric, his impact on public policy historic. His support for the Vietnam War, however, cost him the office he most sought: president of the United States.

Tim O'Connel, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/humphrey-hubert-h-1911-1978

Roy Wilkins, who spent his formative years in the Twin Cities, led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from 1949 to 1977. During those years, the NAACP helped achieve the greatest civil rights advancements in U.S. history. Wilkins favored new laws and legal challenges as the best ways for African Americans to gain civil rights.

-John Fitzgerald, MNOpedia https://www.mnopedia.org/person/wilkins-roy-1901-1981#

Nellie Stone Johnson was an African American union and civil rights leader whose career spanned the class-conscious politics of the 1930s and the liberal reforms of the Minnesota DFL Party. She believed unions and education were paths to economic security for African Americans, including women. Her self-reliant personality and pragmatic politics sustained her long and active life.

Tom Beer, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/johnson-nellie-stone-1905-2002

Cecil Newman was a pioneering newspaper publisher and an influential leader in Minnesota. His newspapers, the Minneapolis Spokesman and the St. Paul Recorder, provided news and information to readers while advancing civil rights, fair employment, political engagement, and Black pride.

Daniel Bergin, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/newman-cecil-1903-1976

With a career spanning fifty years, Anna Arnold Hedgeman was an educator, civil rights advocate, and writer. In 1963, she was the only woman on the planning committee for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Tina Burnside - MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/hedgeman-anna-arnold-1899-1990

St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood ran roughly between University Avenue to the north, Selby Avenue to the south, Rice Street to the east, and Lexington Avenue to the west. African American churches, businesses, and schools set down roots there in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, creating a strong community. Construction of Interstate-94 (I-94) between 1956 and 1968 cut the neighborhood in half and fractured its identity as a cultural center.

Eshan Alma, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/rondo-neighborhood-st-paul

Black students at the University of Minnesota staged a twenty-four-hour protest at Morrill Hall, the school’s administrative building, in 1969. The demonstration led to the creation of the university’s Afro-American Studies Department.

Tina Burnside, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/morrill-hall-takeover-university-minnesota

On the night of July 19, 1967, racial tension in North Minneapolis erupted along Plymouth Avenue in a series of acts of arson, assaults, and vandalism. The violence, which lasted for three nights, is often linked with other race-related demonstrations in cities across the nation during 1967’s “long hot summer.”

Susan Marks, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/civil-unrest-plymouth-avenue-minneapolis-1967