10 Reform Minded at the Turn of the Century: The Populist and Progressive Eras

As we have seen, late 19th-century mass immigration, industrialization, and urbanization fundamentally transformed the nation and the state. The massive scope and scale of these changes, along with the breakneck speed at which they transformed how Minnesotans lived and worked, resulted in a number of unsettling, if unintended, consequences. Beginning during the later decades of the 19th century and continuing through the first decades of the 20th century, Minnesotans joined the rest of the nation in attempts to address the less desirable side effects of this transformation. In a general way, these attempts can be organized into three developments: The Populists movement, the rise and decline of organized labor, and the Progressive Era.

In the political sphere, farmers feeling exploited by railroad companies, flour millers, industrialists, and Eastern financiers joined with equally mistreated urban laborers in a populist movement that threatened to reshuffle the two-party political system. Minnesotans Oliver Kelley and Ignatius Donnelly were among the leaders of the Populist movement that began with the creation of the Grange during the 1860s and culminated with the formation of the People’s Party in the 1890s.

As populists fought in the political arena, workers flocked to labor unions in an attempt to combat low pay, poor working conditions, long hours, child labor, and lack of worker protections. Like the Populists, organized labor grew rapidly after the Civil War but declined sharply by the end of the century. Confrontations between workers and company owners earlier in this period were marked by violence that often turned public opinion against workers. In response, unions formed in an attempt to organize workers for joint, thoughtful, concerted action. The inclusive Knights of Labor (KOL) was established in Philadelphia in 1869 and opened its membership to most skilled and unskilled workers, including both women and African Americans. By 1888, membership reached 700,000 (including 10,000 Minnesotans). That same year, however, violence during a KOL rally in Chicago’s Haymarket Square turned public opinion against the organization and its influence, and its membership plummeted. Two years earlier, in 1886, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) formed and organized skilled workers into craft unions. Unlike the KOL, however, the AFL was exclusive and closed its ranks to unskilled workers, women, and people of color. Early in the following decade, two failed high-profile strikes further diminished the power of organized labor. In 1892, the Homestead Strike in Pennsylvania turned violent and ended without the union’s demands being addressed. And then, in 1894, the Pullman Strike stopped the nation’s railroads and induced the federal government to get involved and crush the strike. As a result, when the country moved into a new century, organized labor struggled to combat the dismal conditions many workers faced.

Both Populists and union members fought for reforms at the close of the 19th century. As the new century dawned, their efforts expanded into a larger Progressive Era that defined the first two decades of the 20th century. Progressives sought to address and correct the ills of American society by ending political corruption, reforming government to make it more efficient and effective, and offsetting the societal ills resulting from urbanization and industrialization. Spurred on by what President Theodore Roosevelt called muckraking journalists, Progressives fought for the common good in the intellectual, cultural, and political spheres and at the local, state, and national levels.

At the local level, college-educated women established settlement houses in large cities to assist immigrant and urban poor with housing, healthcare, education, and employment. Progressives worked to reform corrupt local government and make it more accountable to the working classes. At the state level, governors like “Fightin’ Bob” Lafollette in Wisconsin and Minnesota’s own “Honest John” Lind pushed reforms that expanded democratic participation and worked to make state government more accountable to voters. Nationally, the 20th-century’s first three presidents – Republicans Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) and William Howard Taft (1909-1913) and Democrat Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921) – all oversaw progressive reforms including: regulation of large corporations and public health-related industries, conservation of natural resources and places, and reformation of the tax system and banking structures. The 16th Amendment (graduated income tax), 17th Amendment (direct election of senators), 18th Amendment (prohibition of alcohol), and 19th Amendment (women’s suffrage) are all Progressive era constitutional adjustments.

In all levels and aspects of the Progressive Era, from local settlement houses to the passage of the 19th Amendment, women played a significant role. Minnesotans like Clara Ueland joined national leaders to force change in not only acquiring the vote, but subsequently using newly won political power to push other progressive reforms. African Americans, too, worked to lay the groundwork for the emerging fight for Civil Rights as Minnesota attorney Fredrick McGhee joined national leaders like WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington in a national debate over the best way to achieve equality. The NAACP, which would come to play a leading role in this struggle, was also established during this period.

Progressive era reforms brought much-needed attention to issues that plagued the country at the beginning of the 20th century. In many cases, reforms resulted in positive changes that we often take for granted today. However, in working on behalf of social justice, Progressives at times slipped into advocating social control in xenophobic attempts at regulating immigrant populations, curtailing African American quests for more equal treatment, and pushing back against industrial workers’ attempts to achieve better employment treatment. These controls also resulted in attempts to end alcohol consumption and prostitution and regulate leisure activities and public schooling.

In all aspects of these reform impulses – Populism, organized labor, and Progressivism – Minnesotans played a role locally and nationally.

Populism

Section Highlights

- The Grange, established by Oliver Kelley in the late 1860s, created a social, educational, and cooperative organization for farmers.

- Ignatius Donnelly gained notoriety as a granger before founding the short-lived Anti-Monopoly Party and playing a prominent role in the establishment of the People’s Party.

- Populism reached its high point in the 1890s with the emergence of the People’s Party.

- Eva McDonald Valesh was a prominent journalist, labor activist, and Populist speaker.

Populism in Minnesota and beyond sought to draw together discontented farmers and laborers into a political force able to combat the political might of big business interests. In Minnesota, populism began with struggling farmers and the organization of the Grange. While farmers were able to acquire free land through the Homestead Act or purchase more desirable plots inexpensively from railroad companies, nearly everything else about farming was a struggle. Unpredictable weather, natural disasters such as the grasshopper plague of the early 1870s, and a mysterious and fluctuating market for crops all made farming the Minnesota frontier difficult at best.

In addition, Midwestern farmers felt isolated and exploited by railroads, grain elevator operators, flour millers in Minneapolis, and an unfriendly national currency system. First, railroads that provided service to rural farming areas had no competition and therefore set freight rates at whatever they wanted. Second, grain elevators – often owned by railroad companies – that weighed, graded, and stored grain before shipment lacked any kind of regulation and short-changed farmers. Third, by 1876, a handful of large corporations controlled the flour milling industry in Minneapolis and formed the Minneapolis Millers Association that controlled wheat purchasing to keep prices low. And finally, a tight monetary policy increased the value of currency, which resulted in farmers being forced to pay back loans for equipment in a currency worth more than when the loans were made (making it more expensive).

In this bleak environment, the Grange emerged as an early advocacy organization for farmers in Minnesota and beyond. Having served as a federal agent involved in assessing the devastation in the post-Civil-War South, Oliver Kelly became convinced that farmers needed a social and educational organization that would allow them to collaborate in the market, support farmer-friendly government policies, and share the latest agricultural innovations. In 1867, Kelley and some associates formed the National Grange in Washington, D.C. in hopes of tying together farmers across the nation into a social fraternity. Three years later, in 1869, Kelley oversaw the organization of the required 15 local grange chapters and established the Minnesota State Grange – the first in the nation. Five years later, Minnesota boasted 450 local Granges.

Although the Grange was not a political party – it never ran candidates for office – it did attempt to push proposed legislation that initially focused on railroad-company monopolies. Minnesota Grange efforts resulted in several railroad regulatory attempts in the 1870s that were ultimately undermined by difficult economic conditions and a lack of enforcement mechanisms. But their grassroots efforts did eventually pay off – in 1887, growing public calls from all corners of the country to regulate railroads at the federal level found support in both the Democratic and Republican parties. These pressures resulted in the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which established “just and reasonable” rates along with other controls and regulations.

Postwar Progress: Oliver Kelley and the Grange

The immense popularity and rapid growth of the Grange in the early 1870s was largely a result of the efforts of Ignatius Donnelly. Born and raised in Philadelphia and educated as an attorney, land speculating brought the 24-year-old Donnelly to Minnesota in 1856. As the Civil War loomed, he became active in politics and served as Alexander Ramsey’s Lieutenant Governor in the early 1860s. He went on to serve three terms in the US Congress before a falling out with Ramsey alienated him from the Republican Party. By 1872, he had found a calling with the Grange and became its most prominent and effective speaker. Donnelly pushed the Grange to move further into politics, and when it refused, he formed the Anti-Monopoly Party in 1873, eventually splintering the Grange and pushing it into a downward spiral with plummeting membership. Finding some electoral success, the Anti-Monopoly party partnered with the Democrats to push farmer-friendly railroad regulations. Shortly thereafter, the Anti-Monopoly Party merged with the short-lived Greenback Party and focused on currency reform.

By the late 1880s the national, if fragmented, Farmers Alliance movement gained momentum in rural Minnesota just as organized labor was making inroads with Minnesota’s urban workers. Donnelly, seeing an opportunity to facilitate the melding of these two exploited groups, threw himself back into protest politics. By the early 1890s, he was playing a leading role in the emergence of the People’s Party that held its first national convention in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1892. Having been active in Midwest politics for three decades and an accomplished author, Donnelly was the most well-known politician at the convention and the primary author of the party’s platform. In it, he painted a dire picture of the nation, stating: “The people are demoralized…. The newspapers are largely subsidized or muzzled, public opinion silenced, business prostrated, homes covered with mortgages, labor impoverished, and the land concentrating in the hands of capitalists. The urban workmen are denied the right to organize for self-protection, imported pauperized labor beats down their wages, a hireling standing army, unrecognized by our laws, is established to shoot them down…”[1] He then declared that the new People’s Party sought to “restore the government of the Republic to the hands of the ‘plain people,’” and announced a platform that, among other things, called for:

- A subtreasury plan

- Free coinage of silver to increase the money supply

- A graduated income tax

- Immigration restrictions

- An eight-hour workday

- Government ownership of railroads, telephone, and telegraph

Although Donnelly is the best-known populist leader from Minnesota, others certainly played important – if less remembered – roles as well. Eva McDonald Valesh was one of these Minnesotans. Journalist, union advocate, and sought-after political speaker, Valesh had arrived in Minneapolis by way of Stillwater in the mid-1870s. A member of the typographers’ union, she worked as a typesetter before she began writing for the St Paul Globe in 1888 at the age of just 22. For more than a year, Valesh went undercover to expose the long hours, low wages, and dismal conditions faced by women working in various capacities across the twin cities. Her articles, published under the pseudonym “Eve Gray,” earned her high praise from other populists and acclaim in the expanding labor movement. Soon, she was speaking both locally and nationally on behalf of workers organizing and becoming politically active. She worked closely, although not always seamlessly, with Donnelly and other populists in the Midwest before leaving Minnesota in 1896. She finished her career on the East Coast, continuing her work as a journalist and union activist.

Women in Minneapolis History: Eva McDonald Valesh

The People’s Party 1892 presidential nominee, James B Weaver, won a million votes but finished a distant third behind Republican Benjamin Harrison and the Democratic winner, Grover Cleveland. In 1896, the Democratic Party co-opted the People’s Party’s issues, and the latter found itself forced to support William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee, whom Valesh introduced on his campaign stop in Minneapolis. Bryan ended up losing to Republican William McKinley in the general election – a defeat from which the People’s Party could not recover. Although the party ceased to exist after 1896, the issues it advocated for became political causes that outlasted the party.

Organizing Labor

Section Highlights

- Late 19th-century workers in Minnesota and the nation faced dismal conditions, including long hours, low pay, dangerous working environments, and no worker protections.

- The Knights of Labor was an inclusive national union that organized skilled and unskilled workers while opening its membership to women and people of color.

- The American Federation of Labor organized skilled workers according to their craft – it was exclusive and closed to women and people of color.

- Early Minneapolis and Saint Paul strikes included: Streetcar workers (1899), Great Northern Railway employees (1894), and flour millers (1903).

- The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance emerged in the early 1900s and worked to keep the city free of organized labor.

- The Industrial Workers of the World was a radical union that opposed the capitalist system and hoped to organize all workers into one big union.

- Miners and timber workers in northern Minnesota struck in 1907, 1916, and 1917.

- While most strikes were initially unsuccessful, employers often provided some worker concessions after the strikes were broken.

The struggle for better working conditions, shorter hours, improved pay, worker protection, and workplace regulations went hand-in-hand with the Populist agenda and were among the reforms later Progressives sought. Late 19th-century working conditions in Minnesota and the nation were abysmal compared to today’s standards. Most workers worked between 10 and 14 hours a day, six to seven days a week; child labor of kids as young as 12 was common; there was no federal or state mandated minimum wage; there were no workplace safety assurances; workers received no paid time off or compensation for being injured on the job. As Populists sought to make workers politically active, labor unions attempted to organize them into united fronts that could effectively challenge their workplace mistreatment by large corporations.

Union activity began in Saint Paul in the 1850s. In 1873, union leaders formed the state’s first federation – Workingmen’s Association Number One. Five years later, in 1878, Minneapolis workers established the state’s first Knights of Labor branch – by 1886, the KOL had a Minnesota membership of 10,000, and the organization held its two-week convention in Minneapolis the following year. By the late 1880s, however, the KOL was suffering from a tattered public image in the wake of the Haymarket Square fiasco and was struggling to provide effective representation for its workers. As it declined, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) – a more restrictive federation of skilled laborers organized by craft – gained prominence nationally and in Minnesota. Founded in 1886, by 1890, the AFL had begun establishing a presence in Minnesota cities as it worked within the existing labor system for better pay and improved working conditions for its members.

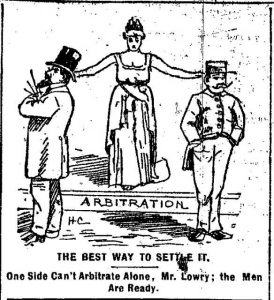

Some of the metropolitan area’s earliest strikes were conducted by railroad workers. Both Minneapolis and Saint Paul had established horse-drawn rail streetcars in the 1870s. By the end of the 1880s, Thomas Lowry had acquired both the Minneapolis and St Paul streetcar companies and was in the process of transitioning the system from horse-drawn carts to steam-powered cable cars (which were nearly immediately abandoned for electricity). To offset the costs of the transition, Lowry reduced worker wages by 15% in April of 1889. In response, 900 employees represented by the Street Railways Employees’ Protective Agency walked off the job. Violence and destruction of property perpetuated by strikers and citizens sympathetic to their plight increased when Lowry refused arbitration and instead brought replacement drivers in from Kansas. Two weeks after the strike began, workers reluctantly returned to their jobs with their demands unmet. The cities had lost thousands of dollars per day over the two-week strike and had to compensate Lowry for property losses.

Four years later, in 1894, a second rail-related strike – this time against James J Hill’s Great Northern line – ended better for the workers. Facing an economic downturn that cut into profits, Hill instituted wage cuts that resulted in an 18-day work stoppage organized by the newly formed American Railway Union. The strike brought Hill to the negotiating table with union President Eugene Debs, where an arbitration ruling forced the Great Northern to rescind the pay cuts. Debs and the ARU went on to represent the workers in the Pullman strike later that year. After stopping virtually all train traffic, the federal government crushed the strike and jailed Debs and other ARU leaders.

In September of 1903, some 1500 Minneapolis flourmill employees represented by an AFL-affiliated union, struck in a quest for higher wages and an eight-hour work day. Mill owners refused requests to negotiate and instead hired replacement workers. Unable to keep the mills shut down, the strike had failed by mid-October. In addition to a clear union defeat, the strike resulted in the emergence of the Minneapolis Citizens Alliance – a business owners’ association that worked to keep Minneapolis clear of effective union organization. The Citizen’s Alliance, supported by banking interests, proved instrumental in defeating a World War 1-era Rapid Transit strike in Minneapolis and Saint Paul, and helped bring the Twin Cities Labor activits to a violent standoff with employers in the Trucker’s Strike that took place in 1934.

Another flashpoint in Minnesota’s early labor history took place in the first decades of the 20th century in northern Minnesota. In 1907, Finnish immigrant miners on the Mesabi Range, organized by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) led over 10,000 miners in a strike against the Oliver Mining Company (a subsidiary of US Steel) to address low wages, long hours, and dangerous working conditions. While the strike lasted several months, it was ultimately broken when the Oliver Company employed strike-breaking replacement workers. Although failing, the WFM strike was the first large-scale work stoppage on the Iron Range and began a long tradition of union activism.

In 1916 and 1917, the Industrial Workers of the World – a radical organization that opposed capitalism in general and advocated that workers consolidate into “one big union” – represented sawmillers, lumberjacks, and mine workers in failed attempts to win better pay and working conditions. In June of 1916, a spontaneous walkout at a Mesabi mine led to a general strike that lasted until September. Although generally peaceful, sporadic violence resulted in three deaths, a government clampdown, and the arrests of IWW leaders ended the strike without direct company concessions. Although technically a failed strike, mining companies did address miners’ concerns shortly afterward by ending the contract labor system, limiting the workday to eight hours, and raising pay rates.

In late December of that same year, the IWW oversaw a strike that began at saw mills operated by the Virginia and Rainy Lake Lumber Company and spread to lumber camps and additional saw mills throughout the region. Sawmill employees were working 12 hours a day, seven days a week, in poor conditions and for low pay. When lumberjacks joined their cause, the sawmills slowed to a standstill. As had happened earlier with the miners’ strike, the lumber companies had the support of local governments and police departments. With IWW leaders arrested, the strike fizzled and ended by February 1, 1917. As had happened with the miners, strikers’ demands were not met by the end of the strike, but owners improved conditions and pay shortly afterward.

Labor organizing efforts in late 19th and early 20th-century Minnesota were wide-ranging. Although they met with limited success and few outright victories, they often earned concessions in the wake of failed strikes and certainly publicized worker exploitation. Many of the struggles that began in this period would continue into the middle part of the 20th century, when labor union activism would become even more effective.

Progressive Minnesota

Section Highlights

- Lincoln Steffens published “The Shame of Minneapolis: The Ruin and Redemption of a City that was Sold Out” in 1903.

- The election of Governor “Honest John Lind” in 1899 is seen as the beginning of the Progressive Era in Minnesota.

- Many of Democratic Governor John Johnson’s reform proposals were enacted under his Republican Successor, Adolph Eberhart.

- The 1904 Supreme Court ruling against James J. Hill’s Northern Securities Company was the first time the Sherman Antitrust Act was enforced against a large corporation.

- Saint Paul Attorney Fredrick McGhee played a prominent role in charting the course for the early Civil Rights Movement.

- U.S. Congressmen Andrew Volstead from Granite Falls wrote the very unpopular enforcement legislation for the Prohibition Amendment.

- Clara Ueland played a prominent role in Minnesota’s suffrage movement.

During the Progressive Era (1896-1920), Minnesota social reform efforts and political activism mirrored efforts undertaken across the nation. Settlement Houses emerged in hopes of addressing urban poverty, even as Lincoln Steffens exposed corruption in Minneapolis’s municipal government. Minnesota politicians followed national trends of reforming state government to combat corruption, enhance efficiencies, and provide more democratic features. Minnesotans featured significantly in the national story as well. For example, James J Hill‘s railroad monopoly was busted up as President Theodore Roosevelt made a name for himself as a trustbuster, and Saint Paul’s Fredrick McGhee worked with other African American leaders, laying the groundwork for the budding Civil Rights Movement. Finally, the national drives to curtail alcohol consumption and extend the right to vote to women had robust Minnesota backing.

Muckraking journalists spurred on many Progressive-Era reform movements. The January 1903 edition of McClure’s Magazine included the second installment of Lincoln Steffens’ series recounting corruption in American cities, later compiled into a book called The Shame of the Cities. Serving as the cover story for the issue, the article was titled: “The Shame of Minneapolis: The Ruin and Redemption of a City that was Sold Out.” In it, Steffens recounted widespread corruption orchestrated by former Minneapolis Mayor Albert "Doc" Ames that involved placing his brother as Chief of Police and collecting protection payments from gambling dens, brothels, and taverns. The exposure the story generated spurred the city to empanel a grand jury and put Ames on trial. Although the former mayor was able to evade prosecution in a series of five trials, Minneapolis did tidy up its local politics in the wake of this national shaming.

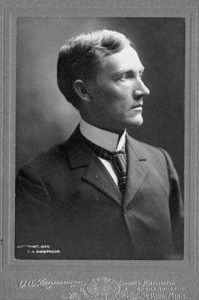

In Minnesota, the beginning of the Progressive Era is often connected to the inauguration of Governor John Lind

in January of 1899. Lind was a Republican Congressman who swayed away from the party during the Populists Movement and captured the governorship with support from Democrats, Populists, and disillusioned Republicans. His political journey, however, left him a “political Orphan,” by his own admission, and he faced a hostile legislature controlled by Republicans that limited his effectiveness as Governor. Regardless, Lind ushered in a host of Progressive Era reforms that, while not enacted during his term, were adopted in the years after he lost office in early 1901. Some of his reform proposals included:

- revising the tax system to take the heavy burden off property owners

- expanding the democratic features of the state government to include direct primaries, initiatives, referendums, and recalls

- enhance state support of education and care for the mentally ill

- increase in railroad taxes

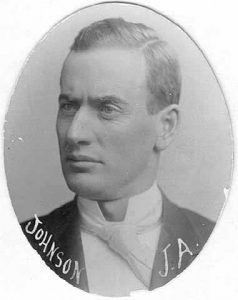

Not only did Governor Lind set the stage for future progressive reforms, but his election began a Minnesota tradition of voter independence. Minnesotans are more willing to cross party lines to vote for who they feel are the most qualified candidates, regardless of political affiliation. This reality resulted in Lind becoming the first Democratic State Governor since Henry Sibley held the office back in the late 1850s, and paved the way for the second person to do so, Democrat John Johnson, in 1905. In both cases, Minnesotans elected Republican legislatures in the same elections they voted in Lind and Johnson.

Minnesota State Capitol

When Governor John A. Johnson took the oath of office on January 4, 1905, Minnesota's third state capitol building had been open for just two days. Saint Paul Architect Cass Gilbert not only designed Minnesota’s new capitol, but he also oversaw its construction, which carried a $4.5 million price tag. The massive building touted the latest technology (its electrical wiring was connected to its own power plant), along with classic grandeur highlighted by a main dome that soared 142 feet high. The gold-leafed quadriga statue, officially named “Progress of the State,” that sits high above the main entrance was added in 1906. The Capitol has been renovated numerous times, most recently between 2013 and 2017 at a cost of $310 million. In addition to its role as the seat of Minnesota government, the state capitol is also a Minnesota Historical Society site, which provides free tours to the public.

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

Johnson was a Democrat from humble origins who was first elected governor in 1904 and held the office from 1905 until 1909, when he unexpectedly died while serving his third two-year term. Johnson’s bipartisanship allowed him to work with a Republican legislature to advance a number of progressive reforms, including regulation of insurance companies, tax reform, railroad regulation, allowing women to own property and sue in court, and the creation of a State Bureau of Labor to oversee working conditions. At the time of his death, Johnson had gained national notoriety in part through his work on insurance reform at the national level. He had unsuccessfully sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1908, and his allies’ aspirations for a 1912 run were dashed by this untimely death in 1909.

During the summer of 1912, Johnson’s Republican Lieutenant Governor Adolph Eberhart – now in his first elected term – oversaw a special session of the legislature that passed a slew of progressive reforms. Among them were the ratification of the Federal Constitutional Amendments allowing for an income tax (16th) and the direct election of senators (17th). The legislature also provided for direct primaries for state offices and reformed the state campaign laws. The following year, Minnesotans made their legislature non-partisan (meaning senators and representatives no longer carried political party affiliations). Although that change did not have much impact on how politicians campaigned or legislated, the legislature remained technically non-partisan until 1973.

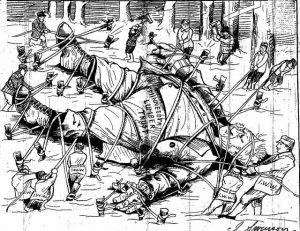

Another Progressive Era push was to regulate big business and protect consumers from monopolies. Nowhere was the threat of monopolies so overt as in the railroad industry. In 1902, when James J. Hill, J.P. Morgan, and associates attempted to combine the Great Northern,the Northern Pacific, and the Chicago and Burlington Railroads into the Northern Securities Company and create an even larger monopoly, the public called for government regulation. The following year, Theodore Roosevelt’s Justice Department employed the Sherman Antitrust Act to challenge the merger in court. In 1904, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the government and broke up the Northern Securities Company, marking one of the first times the Sherman Antitrust Act was successfully enforced against a corporate monopoly.

The Progressive Era social justice reform agenda, although not coordinated in any meaningful way, was largely led by white, educated, middle-class Americans. It is fair to say that the reform priorities of this leadership group did not include addressing inequalities and discrimination faced by African Americans. Regardless, turn-of-the-century African American leaders engaged in a national debate about how best to fight for equal treatment. As Booker T. Washington advocated a piecemeal approach focused on achieving economic opportunities, and W.E.B. Dubois advocated a far less accommodating approach, Saint Paul lawyer Fredrick McGhee

came to play a prominent role in defining the direction the early Civil Rights Movement would eventually follow.

In 1861, McGhee was born into slavery in Mississippi. After the war and emancipation, he moved with his family to Tennessee, where he graduated from college before going on to study law in Chicago. In 1889, he came to Saint Paul and became the first African American to practice law in the state. He was active in politics and by 1892 was serving on the state Republican Central Committee. That same year, he attended the Republican National Convention, held in Minneapolis. Although not designated a delegate, the Republican Party appointed him an at-large presidential elector who would be able to cast a Minnesota electoral ballot on behalf of the Republican candidate. When met with backlash for the honor bestowed on McGhee, the party rescinded the offer during the convention, which did little to support African American causes. In the aftermath of the convention, McGhee left the Republican Party and became one of the state’s leading African American Democrats.

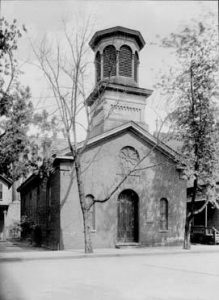

St Peter Claver Church

Around the same time McGhee was changing political affiliations, he also converted to Catholicism. He joined the small African American Catholic Congregation named in honor of Saint Peter Claver, who had been canonized (or bestowed Sainthood status) in 1888. Peter Claver was a Catholic priest from Spain who ministered to enslaved people in Colombia in the early 17th century. In 1892, the congregation constructed a church building for which both Arch Bishop John Ireland and Fredrick McGhee signed the charter. The church moved to its current Oxford Street location in the 1950s and continues its long history as an important religious and cultural pillar in Saint Paul’s African American community.

In July of 1902, McGhee played a central role in bringing the annual meeting of the National Afro-American Council to Saint Paul. Attended by the most prominent African American leaders in the nation, the meeting played a critical role in determining a way forward in the early struggle for Civil Rights. During the meeting, the conservative Booker T. Washington and his supporters maneuvered into control of the organization and its path forward. Disappointed in Washington’s tactics and approach, McGhee then partnered with one of Washington’s most notable critics, W.E.B. Dubois who advocated a more aggressive approach. Together, DuBois and McGhee went on to help found the Niagara Movement in 1905, a precursor to the NAACP established in 1909.

Our Able Attorney

Perhaps the two most remembered Progressive accomplishments came at the very end of the era: Prohibition and Women’s Suffrage. Entry into the First World War gave prohibition advocates momentum that resulted in Congress passing a constitutional amendment outlawing the manufacture, transport, or sale of intoxicating liquors. To become law, the amendment needed ratification by 36 states (3/4th of the total number, which in 1918 was 48). Well before this congressional move, over a dozen states had banned alcohol, and many more had implemented a mechanism allowing the issue to be decided at the county level. In Minnesota, County Option was adopted in 1915, and by the time the Prohibition Amendment was ratified and became law, 46 of 86 Minnesota counties had banned alcohol. In January 1919, Nebraska became the 36th and final required state to ratify the 18th Amendment. Within four days, Minnesota joined three additional states to ratify the amendment, which took effect in January 1920.

Because the 18th Amendment did not include enforcement language but only declared that “the Congress and the several states shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation,” enforcement at the national level fell to the House Judiciary Committee. At that time, Minnesota Congressman from Granite Falls, Andrew J. Volstead, chaired the committee, so drafting the legislation fell on his shoulders. As a result, the National Prohibition Actis commonly known as the Volstead Act. According to historian William Lass, the act “proved to be one of the most unpopular laws in the nation’s history and contributed significantly to the repeal of the 18th Amendment in 1933.”[2] The legislation surprised many by defining prohibited beverages as anything containing an alcohol content of .5% or greater, and therefore included wine and beer among the prohibited beverages. This alienated many who had previously supported Prohibition, assuming it was to ban only distilled spirits. While the national Prohibition experiment did reduce alcohol consumption, it also resulted in a marked increase in organized crime and lawbreaking by formerly law-abiding citizens.

The Progressive Era’s final major achievement, guaranteeing women the right to vote, was over 50 years in the making. The national effort began way back in 1848 when activists met at the Seneca Falls Convention in rural New York and published the Declaration of Sentiments, demanding that the right to vote be extended to women. Every year, beginning in 1878, a constitutional amendment providing this right was proposed in Congress, and every year it failed to receive the requisite number of votes to be sent to the states for ratification. During the waning years of the Progressive Era, as the country fought in World War 1 and debated prohibition, the push for Women’s suffrage gained unmistakable momentum.

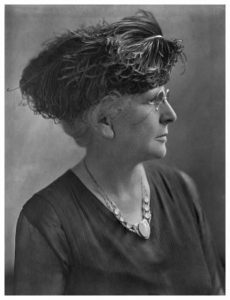

In Minnesota, the suffrage fight was led by Clara Ueland. Born in Akron, Ohio, Ueland came to Minnesota along with her family when she was nine. After working as a teacher, marrying, and raising eight children, Ueland was drawn to the suffrage movement as it gained momentum around the turn of the century. In 1913, she organized the Equal Suffrage Association of Minneapolis. The following year, she organized a march of some 2,000 demonstrators. In 1915, after becoming the president of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association, she organized six women to debate on behalf of women’s suffrage in front of the Senate Elections Committee. Several months later, a woman’s suffrage bill was defeated in the Minnesota Senate by a single vote. When the United States entered World War I, Ueland organized women to take jobs vacated by men in support of the effort.

By the end of 1917, 19 states had extended the right to vote to women. Despite the determined work of Ueland and other Minnesota suffragists, Minnesota was not among them. After President Wilson declared his support for the amendment, Congress finally garnered enough votes in June of 1919 to send the 19th Amendment to the states for ratification. On September 19, 1919, the amendment was ratified by the Minnesota legislature. Ueland, who was in the Senate chamber as it approved the amendment, claimed, “It is my happiest day.” On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th and last required state to ratify the amendment, which became law several days later.[3]

Conclusion

During the age of reform that swept the nation in the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century, Minnesota’s experiences were representative of what was occurring across the nation. At times, Minnesotans led the way, as did Oliver Kelley and Ignatius Donnelly when they rallied farmers to the populist cause, or when Fredrick McGhee helped guide the early Civil Rights Movement. At other times, Minnesota trailed other states in adopting significant reforms, as it did by ratifying the 18th Amendment only after it had become law of the land. In all cases, Minnesotans fought for change and achieved significant successes. As we move into the middle decades of the 20th century, the struggle that Populists, labor organizers, and Progressives began was taken up by a new generation of activists.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Backerud, Thomas. “Populism in Minnesota, 1868–1896.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/populism-minnesota-1868-1896 (accessed April 24, 2022).

Backerud, Thomas. “Progressive Era in Minnesota, 1899–1920.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/progressive-era-minnesota-1899-1920 (accessed April 24, 2022).

Croce, Randy. “Labor and Labor Organizing in Minnesota.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/labor-and-labor-organizing-minnesota (accessed April 24, 2022).

Gilman, Rhoda R. “Eva McDonald Valesh: Minnesota Populist.” In Women of Minnesota: Selected Biographical Essays, edited by Barbara Stuhler and Gretchen Kreuter, 55–76. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1998.

Nathanson, Iric. “African Americans and the 1892 Republican National Convention, Minneapolis,” Minnesota History, Summer, 2008. http://collections.mnhs.org/mnhistorymagazine/articles/61/v61i02p076-082.pdf (accessed April 24, 2022).

Steffens, Lincoln. The Shame of Minneapolis: The Ruin and Redemption of a City that Sold Out. With an Introduction by Mark Neuzil. The Minnesota Legal History Project. http://www.minnesotalegalhistoryproject.org/assets/steffens-%20shame%20of%20mpls.pdf (accessed April 22, 2022)

Stuhler, Barbara. Gentle Warriors: Clara Ueland and the Minnesota Struggle for Woman Suffrage. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1995.

- 1892 People's Party Platform. https://wwnorton.com/college/history/archive/reader/trial/directory/1890_1914/12_ch22_04.htm (accessed April 25, 2022) ↵

- William Lass. Minnesota: A History - Second Edition. (New York: Norton, 1998), 215. ↵

- Norman Risjord. A Popular History of Minnesota (Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005), 174. ↵

Oliver Hudson Kelley was a "book farmer," a man who had learned what he knew about agriculture from reading rather than from direct experience. In 1867, he helped found the National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, the nation's largest agricultural fraternity.

Kate Roberts, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/kelley-oliver-hudson-1826-1913

Ignatius Donnelly was the most widely known Minnesotan of the nineteenth century. As a writer, orator, and social thinker, he enjoyed fame in the U.S. and overseas. As a politician he was the nation's most articulate spokesman for Midwestern populism. Though the highest office he held was that of U.S. congressman, he shaped Minnesota politics for more than thirty years.

Rhoda Gilman, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/donnelly-ignatius-1831-1901

A muckraker is a named coined by President Theodore Roosevelt, for a journalist who used investigative reporting to expose the ills of soceity during the early part of the 20th century. In many cases, these journalists drew attention to causes Progressives then championed. A few of the most well known muckrakers include:

Lincoln Steffens, Shame of the Cities (1904)

Ida Tarbell, The History of Standard Oil Company (1904)

Upton Sinclair, The Jungle (1906)

"Reform!" was the rallying cry of late nineteenth-century America, and John Lind was in the vanguard. His election as the fourteenth governor of Minnesota and the first non-Republican governor of the state in decades heralded a new progressive era.

Minnesota Historical Society, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/lind-john-1854-1930

Federal Income Tax

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.

Direct Election of Senators

The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, elected by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote. The electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State legislatures.

When vacancies happen in the representation of any State in the Senate, the executive authority of such State shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies: Provided, That the legislature of any State may empower the executive thereof to make temporary appointments until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct.

This amendment shall not be so construed as to affect the election or term of any Senator chosen before it becomes valid as part of the Constitution.

Prohibition

Sec. 1 - After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

Sec. 2 - The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Sec. 3 - This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.

Women's Suffrage

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Clara Ueland was a lifelong women’s rights activist and prominent Minnesotan suffragist. She was president of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association when the nineteenth amendment was passed in 1919. That same year, she also became the first president of the Minnesota League of Women’s Voters.

Elizabeth Loetscher, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/ueland-clara-1860-1927

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Fredrick McGhee was known as one of Minnesota's most prominent trial lawyers. In 1905, he was one of a group of thirty-two men, led by W. E. B. Du Bois, who founded the Niagara Movement, which called for full civil liberties and an end to racial discrimination.

Kate Roberts, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/mcghee-fredrick-1861-1912

In the late nineteenth century, a movement arose in Minnesota and across the United States to support the interests of working people and to challenge the power of big business and wealthy tycoons. That movement, called populism, shaped the young state's politics for close to three decades.

Thomas Backerud, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/populism-minnesota-1868-1896

For almost 150 years, the State Grange of Minnesota as an organization has thrived, faded, and regrouped in its efforts to provide farmers and their families with a unified voice. As the number of people directly engaged in farming has declined, the State Grange has shifted its focus toward recruiting a new type of member—often younger—interested in safe, healthy, and sustainable food sources.

Members of the Sunbeam Grange #2, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/state-grange-minnesota

Alexander Ramsey was Minnesota’s first territorial governor (1849–1853), second state governor (1860–1863), and a US senator (1864–1875). Although he directly contributed to the founding and the growth of Minnesota, he also played a major role in removing the area's Indigenous people—the Dakota and Ojibwe—from their homelands.

Jayne Becker, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/ramsey-alexander-1815-1903

The Farmers' Alliance in Minnesota thrived from 1886 to 1892. During this time, the organization achieved the most progress toward its political goals in the state. These included greater regulation of the railroad industry as it impacted the wheat market, elimination of irregularities in the grading of wheat, and minimization or elimination of the middleman in the wheat trade.

Molly Huber, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/farmers-alliance-minnesota

While moving in and out of politics, Donnelly also became a widely read author. The book that most closely connected to his political outlook was Caesar's Column. Published in 1892, the novel presented a dystopian vision of American in the 1980s - a dismal place controlled by ruthless monied elites. The book was an obvious warning of what Donnelly believed might happen if the political movement of exploited farmers and workers failed.

Some of his other notable works include:

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, 1882 a pseudo scientific argument that the submerged continent of Atlantis not only existed, but was also the cradle of civilization.

Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel, 1883 claims that a comet hit ancient earth destroying an advanced civilization and leaving 'drift' layers of gravel in its wake.

The Great Cryptogram, 1888 and The Cipher in the Plays and on the Tombstone, 1899 suggest Francis Bacon wrote plays attributed to William Shakespeare.

An 1890s populist plan calling for the federal government to construct warehouses (or subtreasuries) where farmers could store their crops and receive an immediate government loan of 80% of their current value. Once the crops were sold (within a year of deposit) the farmer then paid back the loan and 1% interest. This proposal was designed to stabilize the market by providing farmers more control over supply so they could realize higher prices for their crops.

A movement during the late 18th century to increase the monetary supply (which would make the dollar worth less), by enacting a policy of unlimited coinage of silver. This cause was championed by the Populist Party in 1892 and then the Populist/Democratic Party in 1896. When Republicans captured the Whitehouse and Congress they enacted the Gold Standard in 1900 - limiting the money supply and increasing the value of the dollar.

A graduated or progressive income tax is a tax structure in-which the rate of tax increases as income increases. Under they concept higher earners pay a higher percent of their income than lower earners.

In 1888, a St. Paul Globe exposé of women's working conditions penned by "Eva Gay" launched the career of Eva McDonald Valesh, a young writer. During the time that she lived in the state, Valesh left a big impression on Minnesota journalism, politics, and labor organizing.

R. L. Cartwrite, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/valesh-eva-mcdonald-1866-1956

The Knights of Labor shaped business and political policy in Minnesota communities in the late nineteenth century by working with the Farmers' Alliance and advocating for shorter work days, equal pay for women, child labor laws, and cooperation between workers.

Molly Huber, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/knights-labor-minnesota

Thomas Lowry was one of the most influential and admired men in Minneapolis at the time of his death in 1909. Streetcars, railroads, libraries, and many other endeavors benefited from his involvement.

Molly Huber, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/lowry-thomas-1843-1909

Wage cuts to employees of the Minneapolis and St. Paul streetcar companies in 1889 prompted a fifteen-day strike that disrupted business and escalated into violence before its resolution. In spite of public support for the strikers, the streetcar companies succeeded in breaking the strike with few concessions.

Linda Cameron, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/twin-cities-streetcar-strike-1889

In September 1903, workers in the Minneapolis flour milling industry coordinated a strike that halted production in fourteen different mills. The striking workers fought for higher wages and an eight-hour day. Though their effort failed, it marked a turning point in the city’s labor history by spurring mill owners and other business leaders to limit unions through the Citizens Alliance, an anti-worker organization.

Molly Jessup, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/minneapolis-flour-mill-strike-1903

When the Twin City Rapid Transit Company (TCRTC) refused to recognize the newly formed streetcar men's union, employees took to the streets of St. Paul and Minneapolis in the fall of 1917 to fight for their civil liberties. The labor dispute challenged state jurisdiction and reached the White House before finding settlement the following year.

Linda Cameron, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/twin-cities-streetcar-strike-1917

Tired of ethnic discrimination as well as dangerous working conditions, low wages, and long work days, immigrant iron miners on the Mesabi Range in northeastern Minnesota went on strike on July 20, 1907. Their strike lasted only two months before it was suppressed with strikebreakers, but it was notable for being the first organized strike on the state's Iron Range.

R.L. Cartwright, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/mesabi-iron-range-strike-1907

The Oliver Iron Mining Company was one of the most prominent mining companies in the early decades of the Mesabi Iron Range. As a division of United States Steel, Oliver dwarfed its competitors—in 1920, it operated 128 mines across the region, while its largest competitor operated only sixty-five.

Alex Tieberg, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/oliver-iron-mining-company

During the summer of 1916, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) coordinated a strike of iron ore miners on the Mesabi Iron Range. The strikers fought for higher wages, an eight-hour workday, and workplace reform. Although the strike failed, it was one of the largest labor conflicts in Minnesota history.

David Lavinge, MNOpeida - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/mesabi-iron-range-strike-1916

In December of 1916, mill workers at the Virginia and Rainy Lake Lumber Company went on strike, and lumberjacks soon followed. The company police and local government tried to crush the strike by running the lumberjacks out of town, but when the strike was called off in February, the company had granted most of the workers’ demands.

Anja Witek, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/iww-lumber-strike-1916-1917

The growth of cities and industry in the late nineteenth century brought sweeping changes to American society. Minneapolis and Saint Paul grew rapidly. Urban labor provided new opportunities for Minnesotans as well as new challenges. Business practices and labor rights became topics of heated debate. The Progressive movement spread amid growing concerns about the place of ordinary Americans in the new urban landscape.

Thomas Backerud, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/progressive-era-minnesota-1899-1920

James J. Hill fit the nickname “empire builder.” He assembled a rail network—the Great Northern (1878), the Northern Pacific (1896), and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy (1901)—that stretched from Duluth to Seattle across the north, and from Chicago south to St. Louis and then west to Denver. He was one of the most successful railroad magnates of his time.

Paul Nelson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/hill-james-j-1838-1916

Albert Alonzo Ames, called “Doc,” was mayor of Minneapolis four times, between 1876 and 1903. Though he earned notoriety as "the shame of Minneapolis" for his involvement in extortion and fraud during his last term in office, Ames also won praise for his work as a doctor and an advocate for veterans.

Tamatha Pearlman, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/ames-albert-alonzo-doc-1842-1911

Henry Hastings Sibley occupied the stage of Minnesota history for fifty-six active years. He was the territory's first representative in Congress (1849–1853) and the state's first governor (1858–1860). In 1862 he led a volunteer army against the Dakota under Ta Oyate Duta (His Red Nation, also known as Little Crow). After his victory at Wood Lake and his rescue of more than two hundred white prisoners, he was made a brigadier general in the Union Army.

Rhoda Gillman, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/sibley-henry-h-1811-1891

John Albert Johnson was Minnesota's first governor born in the state, its first governor to serve a full term in the third state capitol, and its first governor to die in office, making him one of the state's most notable leaders. He also was the first Minnesota governor to bask, albeit fleetingly, in the national spotlight when he sought the 1908 Democratic presidential nomination but lost to William Jennings Bryan.

Minneosta Historical Society, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/johnson-john-albert-1861-1909

On Wabasha Hill, just north of downtown St. Paul, stands Minnesota’s third state capitol building. This active center of state government was built between 1896 and 1905, and was designed by architect Cass Gilbert. Its magnificent architecture, decorative art, and innovative technologies set it apart from every other public building in the state.

Brian Pease, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/structure/minnesota-s-third-state-capitol

Seventeenth Minnesota governor Adolph Olson (A. O.) Eberhart lived the classic American story of an immigrant who achieved success through hard work and ability.

Minnesota Historical Society, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/eberhart-adolph-olson-1870-1944

The Great Northern Railway was a transcontinental railroad system that extended from St. Paul to Seattle. Among the transcontinental railroads, it was the only one that used no public funding and only a few land grants. As the northernmost of these lines, the railroad spurred immigration and the development of lands along the route, especially in Minnesota.

Aaron Hanson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/great-northern-railway

Founded in 1888, St. Peter Claver Church was the first African American Catholic Church in Minnesota. The parish was created by St. Paul’s African American Catholic community and an Archbishop who vowed to “blot out the color line.”

Kathryn Goetz, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/group/st-peter-claver-church-st-paul

Born in County Kilkenny, Ireland, in 1838, John Ireland came to St. Paul with his parents in 1852. He was ordained a Catholic priest in 1861, served briefly as chaplain for the Fifth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment in the Civil War, and was appointed bishop in 1875. By the time he was appointed archbishop of St. Paul in 1888, he was one of the city's most prominent citizens, and he was responsible for recruiting Irish immigrants to settle in communities throughout Minnesota, including Clontarf, Adrian, Graceville, and Ghent.

Kate Roberts, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/ireland-john-1838-1918

Writers of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution took a little more than one hundred words to prohibit the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages. It fell to Minnesota Congressman Andrew Volstead to write the regulations and rules for enforcement. The twelve-thousand-word Volstead Act remained in effect for thirteen years, from 1920 until Prohibition was repealed in December 1933.

Rae Katherine Eighmey, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/national-prohibition-act-volstead-act

Minnesota’s suffragists worked tirelessly to win the vote beginning in the late 1850s, when Mary Colburn delivered what is believed to be the state’s first women’s rights speech. After a long struggle, the dream of equal suffrage took a big leap forward on September 8, 1919, when the state legislature voted to ratify the woman suffrage amendment, making Minnesota the fifteenth state to do so.

Linda Cameron, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/ratification-nineteenth-amendment-minnesota