16 Into A New Century: Minnesota from 1980 to the Present

In his 2005 book, A Popular History of Minnesota, historian Norman Risjord stated:

Historians who venture into the field of state and local history encounter a problem when the narrative reaches the twentieth century. In the past century the federal government, through its regulatory and taxation powers, has touched nearly every facet of American life. Of local decision making there is not much of a story for the historian to tell. Similarly, the development of a mass media and instantaneous communications have tended to homogenize American society, leaving only traces of once-colorful local variations in speech, customs, manners, and dress.[1]

He followed up that observation with a discussion of what he believed was unique or exceptional about Minnesota (we mentioned this in our introduction). But that discussion was not really about our recent history, which is a difficult story for historians to tell.

From the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century until today, our nation has undergone significant changes and continues to face daunting challenges. Although it is difficult to understand the historical significance of such recent history, the recent political turmoil and national challenges impact Minnesotans just as significantly as it does other Americans. As a result, this chapter opens with an overview of national political history that directly impacted Minnesotans and concludes with discussions of Minnesota-specific topics that add to that larger narrative.

A Polarizing Nation – Politics From 1980-2022

Section Highlights

- Since 1980, national politics has grown more partisan and divisive.

- Republican Ronald Reagan served as President from 1981 to 1989.

- Republican George Herbert Walker Bush served as President from 1989 to 1993.

- Democrat Bill Clinton served as President from 1993 to 2001.

- Republican George W Bush served as President from 2001 to 2009.

- Democrat Barack Obama became the first African American to serve as President. He served from 2009 to 2017.

- Republican Donald Trump served as President from 2017 to 2021.

- Democrat Joe Biden was elected in 2020.

- Significant national events that affected Minnesotans during the period include: the AIDS/HIV crisis, the First Gulf War, the presidential election of 2000, the 9/11/2001 terrorist attacks, Hurricane Katrina, wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the 2020 Capitol riot.

In the election of 1980, Republican Ronald Reagan easily defeated the embattled Democratic incumbent, Jimmy Carter, and took office the following January. Four years later, he easily defeated Carter’s Vice President, Minnesotan Walter Mondale, to earn a second term. The Reagan Revolution, as his rise to the Presidency and his years in office are sometimes called, had brought together a new coalition of voters that included wealthy financial supporters advocating for a better business climate, Evangelical Christians worried about cultural issues, and working-class voters frustrated with high taxes and large government. In many ways, this “New Right” was a backlash against the political and social upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s. It opposed legalized abortion, sex education in public schools, and the feminist movement as it advocated for tax cuts, reduction in government programs, and a return to what its supporters believed were traditional family values. Ronald Reagan, the actor-turned-politician who was a pragmatic statesman with a folksy communication style, proved to be a charismatic and effective leader for the movement.

Reagan cut taxes for the wealthy and reduced government regulation in a belief that doing so would create a better business environment, spur investment, and create jobs for the less well-to-do. A growing economy would hopefully produce enough tax revenue to support government spending even as it is taxed at a lower rate. This concept is still advocated by conservatives today and is known as supply-side, or trickle-down economics, but most just called it “Reaganomics” in the 1980s. Although he trimmed spending on social welfare programs, Reagan was never able to balance the budget because he spent heavily on national defense. Under his administration, the federal deficit grew threefold as the tax breaks given to the wealthy never really did trickle down to those below. During the 1980s, the gap between the haves and have-nots grew as the wealthy grew wealthier and the poor grew poorer.

The Reagan Administration exposed a disconnect between the conservative right that adored the president and supported his policies, and a disillusioned liberal left that felt the opposite. The increasing polarization of the American electorate has continued unabated under Reagan’s predecessors from both political parties and is one of the most daunting challenges the country faces today. These fundamental disagreements go beyond tax and spending policies and seem most combustible when applied to cultural or political issues. In the 1980s, the government’s insufficient response to the HIV / AIDS epidemic, which has since taken the lives of 675,000 Americans, and its aggressive response to the drug epidemic, which helped increase the prison population by 4 times over the last decades of the 20th century, provided cultural flash points.

Reagan’s Vice President, George Herbert Walker Bush, won the presidency in 1988. Bush oversaw the end of the Cold War as the Berlin Wall, which had divided the German Capital between a U.S.-supported democratic section and a Soviet-supported Communist section since 1961, came down in 1989, and the Soviet Union imploded in 1991. That same year, the United States led an impressive 34-nation coalition that expelled Iraqi invaders from the oil-rich nation of Kuwait in what is now known as the First Gulf War. Regardless of these foreign policy achievements, Bush was more moderate and lacked the political charisma of his predecessor, and he lost the 1992 election to Democrat Bill Clinton.

Bill Clinton went on to serve two terms as President and presided over a period of extended economic growth aided by the expansion of the information-age economy. He reversed Reagan-era tax policies by increasing taxes on the wealthy and reducing them for the less well-off and small businesses. He oversaw the ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement that had been negotiated under the Bush Administration and created the world’s largest free market by connecting Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Free of Soviet opposition under Clinton, the United States involved itself in localized conflicts in the Middle East, the Balkans, and Somalia to mixed success while regrettably refusing to intervene in an ongoing genocide in Rwanda.

On political and cultural issues, Clinton moved the democratic party toward the center in a realignment that responded to the Republican Party’s move to the right under Reagan. Retreating a bit from a campaign promise to end the military’s ban on LGBTQ people serving by imposing a “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy that pleased no one. He also signed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which defined marriage as a heterosexual union and denied federal benefits to same-sex couples.

Although Clinton remained a popular president, he suffered some significant setbacks, including losing control of Congress to Republicans and failing in a high-profile attempt to reform the healthcare system so that it could provide affordable universal coverage to all Americans. His administration was also saddled with a scandal that made him a polarizing politician and led to his impeachment. While being investigated for sexual harassment, Clinton denied under oath that he had a sexual relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. When evidence presented later undermined his testimony, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives sent two articles of impeachment to the Senate, charging Clinton with perjury and obstruction of justice. The Senate, which requires a 2/3 majority to convict in impeachment hearings, acquitted Clinton of both charges.

The first two decades of the 21st century have been filled with successes and challenges. Our most recent past has tested the American political system and exacerbated a growing rift between the conservative and liberal elements in our society.

Politically, the century began on a shaky note when a tight presidential election between Clinton’s Vice President, Al Gore, and Texas Governor George W. Bush (the son of former President Bush) came down to contested ballots in Florida. The initial tally gave Bush a 527-vote lead, but apparent voting irregularities and significant numbers of disqualified ballots in four heavily democratic counties persuaded Gore to call for a hand recount. The recount bogged down and missed state-imposed deadlines, resulting in a court case that made its way up to the Supreme Court. The nation’s highest court ruled in a 5-4 decision to stop the recount and award Florida’s electors to Bush. As a result, George W. Bush became the 43rd President with a 271 to 266 electoral college victory. In doing so, he became the fourth person to win the presidency despite losing the popular vote (a phenomenon that again occurred in 2016 when Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton despite losing the popular vote).

Later that same year, on September 11, 2001, terrorists affiliated with al-Qaeda hijacked commercial airliners and crashed them into the World Trade Center Towers in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. Passengers on the fourth plane forced it down in rural Pennsylvania before it could reach its intended target. The attack was devastating and the deadliest in human history, taking nearly 3,000 lives, injuring more than 25,000, and causing over $10 billion in infrastructure and property losses. It also fundamentally changed America. In its aftermath, the federal government struggled to balance the urgency of defending the nation from terrorism with that of protecting its citizens’ civil liberties. It also launched a war on terror and endorsed a pre-emptive foreign policy that led to two prolonged conflicts in Afghanistan (2001-2021) and Iraq (2003-2011).

President Bush also faced difficulties from a distressing natural disaster and a severe economic downturn. Shortly after beginning his second term in office (he had defeated Democratic challenger John Kerry in the 2004 election), the country endured another catastrophe when Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in late August of 2005. The storm surge and subsequent flooding left 80% of the city underwater and took the lives of more than 1,800 people. Americans widely criticized the inadequate federal response under the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) that left many stranded New Orleanians with little food, fresh water, or other necessities. Additionally, numerous corporate scandals and the collapse of the real estate sector threw the country into a financial crisis that led to an economic recession that lasted from 2007 to 2009.

Amid this economic turmoil, Americans elected Barack Obama in 2008 and made him the first African American to serve as President of the United States. Obama’s election was as historic as his tenure in office was divisive. With his Democratic Party initially controlling both houses of Congress, Obama was able to continue economic relief efforts begun under President Bush, revise the tax structure to provide more relief to lower earners, and usher through a health care reform bill that sought to provide health insurance to all Americans while maintaining the private-sector insurance structure. Although more popular now, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) initially faced blistering attacks from Republicans, endured a bumpy roll-out, and several Supreme Court challenges that altered the law, but left it mostly in place. Opposition to the health care overhaul allowed Republicans to gain a majority in the House of Representatives in the 2010 midterm election. Although Obama won re-election in 2012, he never again enjoyed Democratic control of both houses of Congress, and therefore, his ability to enact significant legislation waned in the last six years of his tenure.

Political divisions in the nation grew under the Obama Presidency and accelerated after Republican Donald Trump won the election in 2016. Like Obama, Trump enjoyed a Congress controlled by his party and was able to pass a tax overhaul that hoped to simplify the tax code and provide more relief to top earners in hopes that the benefits would trickle down to those below. A first-time, unconventional, and controversial politician, Trump broke Presidential norms and fiercely galvanized those who supported him and those who opposed him. In the midterm election of 2018, the Republicans lost control of the House of Representatives but kept a slim majority in the Senate. The Democratic House went on to impeach the president twice, only to see the Senate acquit in both cases. The last impeachment vote stemmed from President Trump’s purported role in the January 6, 2020, Capitol Riot. Having lost the election to Democratic challenger Joe Biden, President Trump claimed election fraud but was unable to provide any supporting evidence. Nevertheless, he rallied his supporters, who then violently attacked the nation’s capital in a failed attempt to stop the certification of Joe Biden’s election. Two years into Biden’s Presidency, the nation is still transfixed by congressional investigations of a former president who has declared his candidacy for office again in 2024. It is an unfolding political drama that continues to divide the nation.

Minnesota’s Recent Political History

Section Highlights

- In the last half of the 20th century and the first decades of the 21st century, Minnesota politicians have played important roles on the national stage.

- Walter Mondale was a long-time senator, vice president (1977-1981), and presidential candidate (1980).

- Paul Wellstone was a high-profile liberal senator from Minnesota. He served in the Senate from 1991 to 2002.

- Former entertainer Jesse Ventura was a third-party Governor of Minnesota from 1999 to 2003.

- Minnesota has a reputation for being a Democratic state, but it also elects Republicans to state and national offices.

- The three components of the Minnesota state government are typically divided between political parties.

Since the middle part of the 20th century, Minnesota politicians have played an important role in our national political story. Having served as Mayor of Minneapolis during the 1940s, Hubert Humphrey burst onto the national stage when he gave a speech supporting Civil Rights at the 1948 Democratic Convention. In that historic speech, Humphrey famously declared that “The time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states’ rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.” He went on to represent Minnesota in the United States Senate (1949-1964; 1971-1978) and served as Vice President (1965-1969). During the 1968 presidential campaign, Humphrey defeated fellow Minnesotan, DFLer Eugene McCarthy, to win the Democratic nomination before losing the general election to Republican Richard Nixon.

When Humphrey became Vice President, his protégé, Walter Mondale, completed his unfinished term in the Senate. Mondale went on to a long political career that in many ways mirrored Humphrey’s – serving as a vice president and securing the democratic nomination for president. He served in the U.S. Senate from 1964 to 1976 before becoming Jimmy Carter’s Vice President in 1977. The Carter-Mondale administration transformed the role of the Vice Presidency by making it central to the everyday workings of the administration, whereas before it was little more than ceremonial. After Carter lost the 1980 election to Republican Ronald Reagan, Mondale won the democratic nomination for President in 1984. He made history by selecting Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate, making her the first woman in American history to be nominated for the vice presidency by a major political party. In the general election, Mondale lost in a landslide to a very popular and charismatic Reagan; he carried only the District of Columbia and his home state of Minnesota.

Although he served as the Ambassador to Japan from 1993 to 1996 and then as an envoy to Indonesia, most of Mondale’s post-presidential life was spent in the private sector. His last campaign for public office came in the wake of a tragedy that shook his home state of Minnesota. In 2002, incumbent DFL Senator, Paul Wellstone was locked in a fierce re-election campaign with Republican and former Saint Paul Mayor Norm Coleman when he, his wife, daughter, three campaign aides, and two pilots were killed in a small plane crash near Eveleth, MN, eleven days before the election. The Minnesota DFL party asked Mondale to step in in Wellstone’s absence. Mondale agreed and lost by a slim margin to Coleman.

On April 19, 2021, Mondale passed away of natural causes. Former President Jimmy Carter memorialized his friend by saying, “Today I mourn the passing of my dear friend Walter Mondale, who I consider the best vice president in our country’s history.” The current President Joe Biden, who had served in the Senate with Mondale, called Mondale a “dear friend and mentor” who had “defined the vice presidency as a full partnership, and helped provide a model for my service.”

Remembering Walter Mondale, 1928-2021

Throughout our more recent history, Minnesota has gained a reputation as a “blue state” that supports democratic candidates and liberal politics. It has also fostered a reputation for collaborative government and a continued willingness to embrace third-party politicians for state office. That reputation, however, is a bit misleading and only part of a more complicated and evolving story.

When Mondale stepped into the void left by Paul Wellstone in 2002, he was attempting to fill the shoes of one of the Senate’s most liberal voices. Born and raised in the South, Wellstone came to Minnesota in 1969 to teach political science at Northfield’s Carlton College. In 1990, he shocked the state and drew the attention of the nation when he defeated two-term Senate incumbent Rudy Boschwitz in an underfunded campaign characterized by witty, low-budget ads and a green campaign bus. Unapologetically liberal, and repeatedly telling his supporters that “We all do better when we all do better,” Wellstone went on to win a second term in 1996. His third campaign in 2002 was cut short by his untimely death less than two weeks before the election.

Paul Wellstone, 1944-2002

- Campaign Bus, 2006

- Official Senate Photograph

As it had during the early part of the 20th century, Minnesota has proven more willing than most other states to support third-party candidates. At the time of Wellstone’s death, Jesse Ventura was serving his final year as the state’s first third-party governor since the 1930s. A Minneapolis native, Ventura was born James George Janos in 1951. After serving as a Navy SEAL during the Vietnam War Era, Janos became a professional wrestler and adopted the name and persona of Jesse “The Body” Ventura before expanding into acting and, later, politics. Ventura entered politics and served as the mayor of Brooklyn Park in the early 1990s, before unexpectedly defeating Republican Norm Coleman and Democrat Hubert H. “Skip” Humphrey III in the 1998 gubernatorial election. After serving a combative term, he decided not to run for a second. Ventura was not unique for being a celebrity turned politician, but rather for his rejection of the two-party system. Calling himself “fiscally conservative and socially liberal,” he won the election as a Reform Party candidate, but later switched to the Independence Party. In capturing the governorship through grassroots, independent campaigning, Jesse “The Body Politic” Ventura tapped into a then dormant Minnesota legacy that embraced political outsiders and an openness to alternatives to the two-party system.

In addition to the state’s most prominent national politicians being Democrats, the vision of Minnesota as dependably “blue” is furthered by the fact that the state has voted for Democratic presidential candidates in every election since 1976. But these two realities do not tell the whole story. While supporting Democrats for president, Minnesotans often elect to send Republicans to Congress and to serve in state government. Since 1980, only five times have all three components of the state government (the House, Senate, and Governorship) been controlled by the DFL. In the remaining 18 sessions, power has been divided between the two parties. Minnesota’s earlier political history was dominated by the Republican Party.

In the past, the realities of a mixed state government resulted in more bipartisan collaboration. But as the country became more partisan, so too has Minnesota. Recent years have seen more gridlock and combative politics in St Paul and resulted in state government shutdowns in 2005 and 2011. Mirroring the nation, the state is also seeing a growing disconnect between people living in urban areas (specifically the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area), who overwhelmingly support Democratic candidates and policies, and those living in Greater Minnesota, who are much more likely to support Republicans. Regardless of who Minnesotans vote for, Minnesotans vote in higher percentages than the rest of the nation. Since 1980, the state has topped all others in voter turnout during presidential elections with the single exception of 1992, when it finished second to Maine. (see Graph 15.1).

Minnesota and National Voter Participation in Presidential Elections, 1980-2020

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

SOURCES: Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections | The American Presidency Project (ucsb.edu); Minnesota Election Statistics, 1950-2020 (state.mn.us); Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections (uselectionatlas.org)

People

Section Highlights

- According to the 2020 census, Minnesota’s population is 76% Caucasian.

- The Twin Cities metropolitan area continues to be more diverse.

- The Twin Cities metropolitan area is home to the largest Hmong-American community in the nation.

- The Twin Cities metropolitan area is home to the largest Somali-American community in the nation.

The 2020 census counted just over 5.7 million Minnesotans – an increase of 7.6% from 2010. Although the state’s population continued to diversify, it was still predominantly Caucasian. Just over 76% of Minnesotans self-identified as White on the census, while Minnesotans identifying as Black, indigenous, other peoples of color, or those identifying as more than one category accounted for the remaining 24%. Most of the state’s population (55%) lived in the Twin Cities seven-county metropolitan area in 2020. This trend was especially true for the state’s minority populations, whose members were far more likely to be living in the metropolitan area than the population at large. The only exception to this was the state’s indigenous people. While Minneapolis is home to one of the largest and most diverse urban communities of indigenous people, most of the state’s Dakota and Ojibwe people live in Greater Minnesota – many reside in one of the four Dakota communities or the seven Ojibwe reservations. Around 68,500 people identified as indigenous in Minnesota, accounting for about 1.2% of the total population, while an additional 91,300 people identified as a combination of indigenous and another category. Although small, Minnesota’s indigenous communities continue to play a significant role in the state and add to its cultural richness.[2]

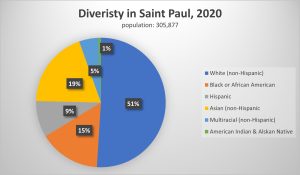

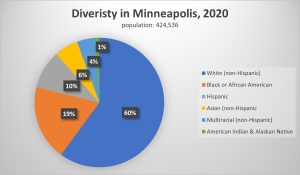

Despite Minnesota’s relatively homogeneous population, during the closing decades of the 20th century and into the opening decades of the 21st the Minneapolis and St Paul metropolitan area continued to diversify (see graphs 15.2 and 15.3). Vibrant immigrant and refugee communities developed during this period. According to the University of Minnesota immigration historian, Saengmany Ratsabout, recently, “most of Minnesota’s immigrants come from Somalia, Mexico, China, India, Laos, and Myanmar. The number of African immigrants in the state grew by 620 percent in the 1990s, and the number of immigrants from Latin America increased by 577 percent. Between 2000 and 2010, Latinx people accounted for … 27.8 percent of the population growth in Minnesota.”[3] In addition to the long established and growing African American and Mexican American communities, Minnesota, and specifically the Twin Cities, is home to a variety of groups that have more recently chosen to make the state their home. This list includes, but is not limited to: Hmong, Somali, Ethiopian, Oromo, Karen, Khmer, Asian Indian, and Filipino.[4] Of these groups, two of the largest and most prominent in the Twin Cities are the Hmong and Somali communities.

Diversity in Minneapolis and Saint Paul, 2020

- Graph 15.2

- Graph 15.3

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

SOURCES: DataUSA: Minneapolis, MN (Minneapolis, MN | Data USA); DataUSE: Saint Paul, MN (St. Paul, MN | Data USA)

Hmong Minnesotans

When American efforts to stop the spread of communism in Southeast Asia failed in the mid-1970s, victorious communist regimes began persecuting those who supported the American efforts. This led to a refugee crisis that brought people from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos to the United States. Prominent among this group, Hmong people, exiled from Laos, came in large numbers to make their homes in and around St. Paul. Today, Minnesota is home to the second-largest Hmong population in the nation, trailing only California. Because over 95% of the state’s 88,215 Hmong residents live in the Twin Cities, the metro area houses the largest Hmong community in the country.

Indigenous to northeastern China, pockets of Hmong migrated south and reached Southeast Asia by the middle of the 1800s. After World War II, Southeast Asian Hmong communities, which practiced subsistence agriculture and depended solely on oral traditions to pass down their history and culture, found themselves caught up in international Cold War politics. Two-thirds of the Laotian Hmong population came to support American efforts to confront communism, and large numbers of men and boys aided the American effort by waging a Secret War against their Communist foes, directed by the CIA. Hmong soldiers assisted downed American pilots and worked to disrupt enemy movement down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In doing so, they sacrificed dearly for the American cause, dying in higher percentages than did the Americans. When the American effort collapsed and the U.S. military withdrew from South Vietnam, all but the highly connected Hmong families were left to fend for themselves in the face of an angry Pathet Lao government determined to murder or “re-educate” those who supported the Americans. Persecuted, some Hmong families subsided for years moving through the jungle, while others fled across the Mekong River to Thailand and into dismal refugee camps before navigating the slow process of immigrating to America.

The first Hmong families arrived in Minnesota beginning in 1975 and began the slow process of acclimating to their new, foreign surroundings. Newly arrived families faced cultural and language challenges, made even more difficult by the forced conversion from rural subsistence to urban living. Government resources, volunteer organizations, and Hmong-run community associations all played a role in the development of today’s vibrant Twin Cities Hmong culture. St. Paul’s Hmong community became the first in the nation to elect a Hmong politician, Mee Moua, to the state Senate in 2002. It also proudly hosts annual celebrations of the Hmong New Year. Furthermore, acclaimed Hmong authors like Kao Kalia Yang and Mai Neng Moua continue to produce popular creative non-fiction work celebrating Hmong culture that reaches a broader audience.

Somali Minnesotans

Minnesota is home to the largest Somali community in the country. While exact population numbers are hard to determine, a 2019 estimate suggested that approximately 69,000 Minnesotans were either born in Somalia or children of Somali immigrants, 80% of whom are U.S. Citizens. Today, most of the Somali American community lives in Minneapolis and the surrounding metropolitan area.

Somalia straddles the equator on the East African coast. France, England, and Italy colonized and divided the nation in the early 20th century. Somalis again gained their independence after World War II and established a democratic government in 1960. Nine years later, General Mohamed Siad Barre seized power by force and destabilized the country. Resistance to Barre’s rule escalated in the 1980s and forced him to relinquish power in 1991. Tragically, the nation descended into decades of chaos and civil war after Barre’s removal as clans and warlords fought for control. In 2010, Somalis established a transitional government supported by the UN and the African Union, and two years later held parliamentary elections for an internationally recognized government. Difficulties with the transition of political power in 2021, along with drought, the climate crisis, economic ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the war in Ukraine, have combined to make ongoing economic, social, and political stability a challenge.

The civil unrest beginning in 1991 displaced over 2.5 million people and forced over a million Somalis to make the difficult decision to leave their nation. By 1992, Somali refugees and asylum seekers began arriving in Minnesota, many after fleeing first to Ethiopia or Kenyan refugee camps. In Minnesota, new arrivals joined an existing small, mostly student population already here. Government agencies, faith-based non-profits, and Somali-run organizations helped the increasing number of immigrants transition to their new lives in Minnesota. Like all immigrant groups, Somali people faced challenges in their new homes. In addition to the difficulty of leaving one’s home and language barriers, historian Anduin Wilhide noted that the Somali experience was even more challenging as refugees “have dealt with multiple traumas; they have survived a civil war, life in refugee camps, and resettlement in a country with very different cultural and religious traditions.”[5]

Somali Minnesotans make up one of the state’s largest Muslim communities, and practicing their Islamic faith, integral to the broader Somali culture, is sometimes difficult in a predominantly Christian environment. Praying five times throughout the day, fasting during Ramadan, avoiding alcohol and pork while eating foods that are processed according to Islamic law, and, for some Somali women, wearing a head covering (or hijab) sometimes present challenges in Minnesota. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, unfairly brought more scrutiny to Muslims living in America, including Minnesota’s Somali community. This situation was made worse by the radicalization of a small number of Somali young men in Minnesota, which led to about 20 returning to Somalia to join the terrorist group Al-Shabaab between 2007 and 2008. In 2016, nine Somali men were convicted or pleaded guilty to conspiring to fight with ISIS in Syria. These high-profile events were devastating for the larger Somali community, who have embraced their Minnesota home and practice mainstream Islam, a peaceful religion. According to Wilhide, the vast majority of “Somalis strongly disagree with the ideas and practices of violent extremists and terrorist organizations like Al-Shabaab, Al-Qaeda, and ISIS. The majority of Somalis advocate for Islam as a religion of peace.”[6]

As the Somali population in the Twin Cities continues to mature, Somali-run community organizations and a growing number of mosques have created a social network that continues to support the growing community. Somali youth increasingly pursue higher education at public and private institutions including St Paul College. Home ownership is also increasing with the help of Somali-run organizations like the African Development Center that provides no-interest loans to home purchasers allowing them to abide by the Islamic law that forbids paying interest.

The Minnesota Somali community has also become involved in local, state, and national politics. In 2017, Ilhan Omar became the first Somali American to serve in the Minnesota legislature after winning the election to House District 60B in 2016. Omar’s history mirrors that of many Somali Minnesotans – she fled Somalia with her family in the 1990s and lived in a Kenyan refugee camp before coming to the United States and eventually Minnesota in 1997. In 2018, she made history again by winning an election to the United States House of Representatives to represent Minnesota’s 5th District, which includes Minneapolis and some surrounding suburbs. She has since been reelected in 2020 and 2022.

A State That Works… For Some

Section Highlights

- In 1973, Time Magazine published an article praising Minnesota as a “state that works.”

- In 2015, The Atlantic published an article praising Minneapolis’ “affordability, opportunity, and wealth.”

- The Minnesota legislature established the Metropolitan Council in 1967.

- The 1971 legislative “Minnesota Miracle” revised the tax and funding structures in the state as they related to local government public school funding.

- The glowing assessments of Minnesota and the Twin Cities ignored the vastly different experiences faced by Minnesotans of color.

- Samuel L. Meyers has named the different experiences between white people and people of color in the state the Minnesota Paradox.

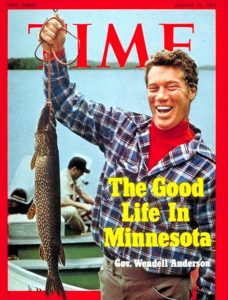

The August 13, 1973, issue of Time Magazine cover featured a smiling Wendell Anderson, flannel-clad and proudly holding a fish in front of a picturesque Minnesota lake. Underneath the outdoorsy Minnesota Governor’s image read “The Good Life in Minnesota.” The cover story, “Minnesota: A State That Works,” heaped praise on the state in its opening paragraphs:

If the American good life has anywhere survived in some intelligent equilibrium, it may be in Minnesota…. Some of the nation’s most agreeable

qualities are evident there: courtesy and fairness, honesty, a capacity for innovation, hard work, intellectual adventure and responsibility…. Politics is almost unnaturally clean – no patronage, virtually no corruption. The citizens are well educated; the high school dropout rate, 7.6%, is the nation’s lowest. Minnesotans are remarkably civil; their crime rate is the third lowest in the nation…. Minnesota nurtures an extraordinarily successful society.[7]

The article went on to praise the state’s vibrant business community, affordability, its “comparatively unspoiled land,” civic engagement, and community fundraising. The end of the piece became a political profile of the up-and-coming governor, but more importantly, suggested that innovative governmental action, specifically the 1967 creation of the Metropolitan Council and the 1971 legislative Minnesota Miracle, was at least partially responsible for Minnesota’s “good life.”

By the 1960s, the growing Twin Cities metropolitan area faced escalating challenges relating to natural resource management, pollution control, transportation, and economic disparities. In 1967, at the urging of local governments, concerned citizens, and business communities, the state legislature established the Metropolitan Council to provide governmental oversight for the seven-county metropolitan area. The council, according to Governor Harold LaVander, “was created to do a job that proved too big for any single community.” Over the next several years, additional legislation provided the Met Council with tools to oversee transportation (now Metro Transit), a regional sewer and water treatment system, a regional parks system, and housing assistance.

In 1971, DFL Governor Anderson, working with a Republican controlled House and Senate, enacted what has since been called the “Minnesota Miracle,” a massive reordering of the state’s tax and funding system, specifically as it related to funding for local governments and public schools. The first part of the miracle, related to local government funding. Prior to the reform, communities within the metropolitan area competed to attract business investment – this served to undercut tax revenues and began to create inequalities across the metro. The legislation created a tax-sharing system that worked through the Metropolitan Council to pool a portion of tax revenues and spend them equally across the seven-county region, significantly reducing inequalities. The second part of the miracle related to how schools were funded. Before the reform, public schools depended on local property taxes for much of their funding. This resulted in property-tax-rich regions having better-funded schools than property-tax-poor areas. Additionally, Minnesotans paid disproportionately high property taxes. The legislation raised state income tax, the sales tax, and taxes on alcohol and tobacco, and took over much of the funding, thereby equalizing public education in the state, and in many cases reducing property taxes.

The tax and spending structures set up in the Minnesota Miracle legislation remained largely in place until 2002, when the legislature began making changes. That its approach proved successful was one of the reasons a 2015 Atlantic article, titled “The Miracle of Minneapolis,” suggested that the Twin Cities mixed “affordability, opportunity, and wealth” better than any other metropolitan area in the nation. The article argued that “a highly unusual approach to regional governance, one that encourages high-income communities to share not only their tax revenues but also their real estate with the lower and middle classes” (put in place largely by the Minnesota Miracle legislation) is responsible for the metro area’s affordable housing, high median income, high college graduation rates, and a disproportionate number of Fortune 500 companies. The article continues to explain that 70% of affordable housing constructed in the 1970s and 1980s was built in “the wealthiest white districts.” And “by spreading the wealth to its poorest neighborhoods, the metro area provides more equal services in low-income places and keeps quality of life high just about everywhere.”[8]

The Minnesota Paradox

When analyzing data regarding quality of life in Minnesota and the Twin Cities, the two articles mentioned above determined that Minnesota is an excellent place to live. Data suggests this is true for most Minnesotans. But because African Americans and other people of color represent a small percentage of the total population (especially outside of the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area), their experiences have been overlooked. As we mentioned earlier toward the end of Chapter 1, University of Minnesota Economist, Samuel L. Myers Jr., has analyzed the different experiences in Minnesota by ethnicity. He found that while Minnesota is one of the best places to live by a variety of measures for white people, it is also one of the most difficult places to live for people of color. He has named this phenomenon the “Minnesota Paradox.” Myers points out that “measured by racial gaps in unemployment rates, wage and salary incomes, incarceration rates, arrest rates, home ownership rates, mortgage lending rates, test scores, reported child maltreatment rates, school disciplinary and suspension rates, and even drowning rates, African Americans are worse off in Minnesota than they are in virtually every other state in the nation.”[9]

Clark, Castile, and Floyd: Black Lives Matter

Section Highlights

- Minnesota has been thrust to the forefront of a national confrontation over police departments’ disproportionate use of deadly force during confrontations with African American men.

- Jamal Clark was killed in Minneapolis by a police officer during a confrontation in 2015.

- Philando Castile was killed by a police officer during a traffic stop in Falcon Heights in 2016.

- George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis by police officer Derek Chauvin in 2020.

- Black Lives Matter is leading the protests over police shootings of African American men in Minnesota and the nation.

Seven months after the publication of “The Miracle of Minneapolis,” Minneapolis police shot and killed Jamal Cark, an unarmed African American 24-year-old man, while responding to a domestic disturbance call in Northeast Minneapolis. Clark’s death highlighted for the larger population what people of color in Minneapolis had known for generations – that the state does not work the same for everyone. The 2015 Atlantic article completely ignored race in its glowing assessment of the Twin Cities, and the 1973 Times piece dismissed it by commenting, “Blacks rioted in Minneapolis in 1966 and 1967, but with only 1% of the state’s population, they have not yet forced Minnesotans into any serious racial confrontation.” Sadly, our most recent history witnessed the Minneapolis and Saint Paul region propelled to the very front of a national and international racial confrontation. Clark’s death resulted in an outpouring of anger and an 18-day Black Lives Matter protest; the Minneapolis police officers involved were not charged in the incident nor disciplined by the department. [10]

Sadly, Clark is not alone in being a victim of police shootings in Minnesota. Like the rest of the nation, Minnesota is struggling to address the disproportionate use of deadly force faced by its communities of color. In July of 2016, St Anthony police officer Jeronimo Yanez pulled Philando Castile over in the Saint Paul suburb of Falcon Heights because he mistook him for a robbery suspect. While retrieving his driver’s license, Castile informed Yanez that he was legally carrying a gun. After repeated orders from Yanez to not pull out the gun and assurances by Castile that he wasn’t, Yanez, unable to clearly see Castile’s hand, fired seven shots into the car. Five bullets hit Castile, and he died from the wounds soon after. Castile’s girlfriend and their four-year-old daughter were in the car at the time of the shooting. Castile had graduated from Central High School and was a long-time beloved staff member of the St Paul Public Schools nutrition services department. Like with Clark just months before, the killing sparked outrage and protests in the Twin Cities and across the nation. Although charged, a jury acquitted Yanez. The St. Anthony Police Department quickly terminated his employment after the verdict, and the city paid out a wrongful death suit.

Four years later, in May of 2020, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd, an unarmed African American man, by kneeling on the back of his neck for nearly nine minutes as other police officers stood by and shocked bystanders streamed the gruesome event on social media. Unlike the split-second decisions involved in the Clark, Castile, and several other police killings, Floyd’s death was not a result of a quick, panicked reaction, but rather a drawn-out, slow decision. Chauvin was charged, convicted, and sent to prison for murder. Other officers who stood by and did not intervene were convicted of lesser crimes associated with Floyd’s death and sent to prison. The murder drew worldwide condemnation and a concerted effort led by Black Lives Matter in Minneapolis and elsewhere to reimagine how police departments are structured and operated. Two years later, it is uncertain what meaningful changes will come out of the outrage caused by the deaths of Clark, Castile, Floyd, and many others across Minnesota and the nation.

Conclusion: Looking Forward

Without question, it is difficult to conclude a history of Minnesota with accounts of devastating police killings of Black men in the Twin Cities. Sadly, it is as necessary as it is uncomfortable and unsettling. As we have seen, Minnesota’s past is filled with inspirational, uplifting stories as well as those that are devastating and heart-wrenching. Both are important and help us use our past to chart a collective path forward. As Paul Gruchow stated in his essay, we read at the outset of the course, “history gives us the imagination…to plan for the future.”

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Lee, Mai Na M. . “Hmong and Hmong Americans in Minnesota.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/hmong-and-hmong-americans-minnesota (accessed December 5, 2022).

Kenney, Dave and Thomas Sailor. Minnesota in the ‘70s. (St Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2013).

Myers, Samuel Jr. “The Minnesota Paradox.” Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota. The Minnesota Paradox | Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs (umn.edu)

Sturdevant, Lori. “Politics in Minnesota .” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/politics-minnesota (accessed December 5, 2022).

Vang, Chia Youyee. Hmong in Minnesota. (St Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2008).

Wilhide, Anduin. “Somali and Somali American Experiences in Minnesota.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/somali-and-somali-american-experiences-minnesota (accessed December 5, 2022).

Yusuf, Ahmed Ismail. Somalis in Minnesota. (St Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2013).

- Norman Risjord, A Popular History of Minnesota (Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005), 232. ↵

- “Demographic Trends: American Indian Health Status in Minnesota: 30-Year Retrospective,” Minnesota Department of Health, July 2021. Available online as of November 28. 2022 at Demographic trends: American Indian health status in Minnesota (30-year retrospective) (state.mn.us). ↵

- Ratsabout, Saengmany. "Immigrants and Refugees in Minnesota: Connecting Past and Present." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/immigrants-and-refugees-minnesota-connecting-past-and-present (accessed November 28, 2022). ↵

- For an overview and personal stories from many of these groups, see the Minnesota Historical Society’s online resource: “Becoming Minnesotan: Stories of Recent Immigrants and Refugees” Becoming Minnesotan | Stories of Recent Immigrants and Refugees (Becoming Minnesotan | Stories of Recent Immigrants and Refugees (mnhs.gitlab.io) ↵

- Wilhide, Anduin. "Somali and Somali American Experiences in Minnesota." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/somali-and-somali-american-experiences-minnesota (accessed December 3, 2022). ↵

- Wilhide, Anduin. "Somali and Somali American Experiences in Minnesota." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/somali-and-somali-american-experiences-minnesota (accessed December 3, 2022). ↵

- “American Scene: Minnesota: A State That Works,” Time Magazine, August 13, 1973, AMERICAN SCENE: Minnesota: A State That Works - TIME ↵

- Thompson, Derek. “The Miracle of Minneapolis,” The Atlantic, March 2015, The Miracle of Minneapolis - The Atlantic ↵

- Samuel L Myers Jr. “The Minnesota Paradox,” Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs – University of Minnesota, July 6, 2022, https://www.hhh.umn.edu/research-centers/roy-wilkins-center-human-relations-and-social-justice/minnesota-paradox ↵

- “American Scene: Minnesota: A State That Works,” Time Magazine, August 13, 1973, AMERICAN SCENE: Minnesota: A State That Works - TIME; Thompson, Derek. “The Miracle of Minneapolis,” The Atlantic, March 2015, The Miracle of Minneapolis - The Atlantic ↵

One of the most accomplished politicians in Minnesota history, Walter “Fritz” Mondale served as vice president under Jimmy Carter and ran an unsuccessful presidential campaign with running mate Geraldine Ferraro in 1984. During his long career, he advanced consumer rights as Minnesota's attorney general, maneuvered civil rights and procedural reform legislation as a US senator, and revitalized the notoriously stagnant vice presidency during the Carter administration.

Samuel Meshbesher, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/mondale-walter-1928-2021

Hubert H. Humphrey, a giant of Minnesota politics, was one of the most influential liberal leaders of the twentieth century. His political rise was meteoric, his impact on public policy historic. His support for the Vietnam War, however, cost him the office he most sought: president of the United States.

Tim O'Connel, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/humphrey-hubert-h-1911-1978

Paul Wellstone once described himself by saying, “I’m short, I’m Jewish, and I’m a liberal.” He was also a Southerner, a college professor, and a rural community organizer who became a two-term U.S. senator from Minnesota. He inspired a passionate following, in Minnesota and among liberals nationwide. Wellstone died in a plane crash while running for a third term.

Paul Nelson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/wellstone-paul-1944-2002

African Americans have lived in Minnesota since the 1800s. The local African American population developed from individuals who were born in the state as well as those who migrated to Minnesota from other states in search of a better life. Despite being subjected to discrimination and inequality, African Americans established communities and institutions that contributed to the vibrancy of the state. This article defines African Americans as Americans who are descendants of enslaved black Africans in the U.S. and does not include immigrants or refugees from Africa (for example, Somali and Oromo people.

Tina Burnside, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/african-americans-minnesota

Since the early 1900s, Latinos have been a productive and essential part of Minnesota. Most of the earliest Minnesotanos were migrant farm workers from Mexico or Texas and faced obstacles to first-class citizenship that are still being addressed. They overcame the instability associated with migratory work by establishing stable communities in the cities and towns of Minnesota. Latinos faced, and still face, discrimination—both racial and the kinds common to all immigrants, migrants, and refugees.

Jeff Kolnick, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/minnesotanos-latino-journeys-minnesota

The Hmong first arrived in Minnesota in late 1975, after the communist seizure of power in Indochina. They faced multiple barriers as refugees from a war-torn country, but with the help of generous sponsors, have managed to thrive in the Twin Cities area, a region they now claim as home. Today, many Hmong promote the economic, social, and political diversity of the state.

Mai Na M. Lee, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/hmong-and-hmong-americans-minnesota

Although the first Somalis to arrive in Minnesota were students and scholars, the majority of Somalis who live in the state in the 2010s came as refugees fleeing a civil war in their homeland. Like earlier immigrant communities, Somalis have struggled to figure out where they belong and how to maintain cultural traditions as they adjust to living in a new place. They have faced unique challenges as African Muslims living in a historical moment (post-9/11) when their religion is being scrutinized and their home country is in the news for instances of Islamic terrorism and piracy.

Anduin Wilhide, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/somali-and-somali-american-experiences-minnesota

After Kenya, which supports about half a million native Oromos, the state of Minnesota has the largest population of Oromo people outside their homeland in Ethiopia. As a result, Oromo people worldwide know the Twin Cities as Little Oromia. The story of how the area came to earn this name is intertwined with Oromo culture, politics, migration, religious faith, and adaptation to life in the United States in the late twentieth century.

Teferi Fufa, MNOpedia - Oromos in Minnesota: The Making of Little Oromia | MNopedia

In a special state senate election held in January of 2002, Mee Moua became the first Asian woman chosen to serve in the Minnesota Legislature and the first Hmong American elected to any state legislature. Her win in St. Paul’s District 67 made national news and had lasting political and cultural impacts on the Hmong community.

Tiffany Vang, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/event/election-mee-moua-minnesota-senate-2002

The Hmong New Year in St. Paul is a unique annual event encapsulated into a weekend celebration held at the end of November. Since 1977, Hmong people have gathered in the city to meet, eat, celebrate the harvest, and enjoy cultural performances. Though the event is rooted in the agricultural history of the Hmong people and their religious traditions, it has found a new expression in St. Paul—the home of one of the largest communities of Hmong outside Southeast Asia.

Kong Vang, MNOpedia - Hmong New Year, St. Paul | MNopedia