4 Europeans: Exploration and Political Claims

When Christopher Columbus reached the Caribbean on October 12, 1492, he fundamentally and irreversibly altered world history. While not the first mariner to reach the West from the East, Columbus’s voyage was the first to establish an ongoing connection between the two isolated hemispheres. This new connection facilitated a swap of people, plants, animals, technology, culture, and pathogens that historians call the Columbian Exchange. This exchange touched nearly every corner of the globe, and in the Americas, it quickly became catastrophic. Pathogens carrying deadly diseases to which indigenous American populations had no immunity rippled out from the Caribbean, and as contact spread throughout the Americas, American indigenous populations endured devastating population losses that reached perhaps 90% of their pre-contact levels. In all corners of the Western Hemisphere, including Minnesota, the Columbian Exchange left what historian Francis Jennings has called “a widowed land.”

As European nations – most notably Spain, France, and Great Britain – attempted to reap the rewards of Columbus’s “discovery,” they fought each other in a series of wars for empire that would, by the second half of the 18th century, define the political future of the Americas. By 1763, Great Britain had wrestled away France’s North American Empire, only to lose the heart of its colonial holdings in 1783, after its American colonists successfully revolted against imperial control.

These events, of course, impacted not only European colonists and North American maps drawn in Europe, but also American indigenous peoples living in all corners of what became the United States. Beginning in the middle of the 17th century, growing European colonies, exploration, and an ever-expanding fur trade set people in motion and upended the status quo. Minnesota’s unique position at the western edge of the Great Lakes, along with the fact that it contained the starting point of the Mississippi River, made the area particularly important throughout this period. Not only did Minnesota’s geography and resources draw European explorers and traders to the area, but diplomats repeatedly used the Mississippi River as a political dividing point on their ever-changing maps.

Before this quest for empire, we do know that Viking mariners from Scandinavia established a short-lived settlement in what is today Newfoundland, Canada, around 1021 CE. An imaginative theory suggesting that the Vikings reached Minnesota in 1362 is unlikely but continues to be debated. By the 17th century, the western Great Lakes, including what would become Minnesota, were claimed by France as it strove to convert indigenous peoples to Catholicism, explore the region, and extend a lucrative fur trade. This fur trade and ballooning English colonies in New England pushed people into motion and, among other things, helped encourage the Ojibwe to continue their migration from northern sections of the Atlantic seaboard into the western sections of the Great Lakes region, then inhabited by the Dakota. After the French defeat in the French and Indian War in 1763, it ceded the territory east of the Mississippi River to Great Britain and passed lands west of the river to Spain.

Minnesota Vikings?

Section Highlights

- Vikings established a short-lived settlement in what is today Newfoundland, Canada around 1021 CE.

- Olof Ohman claimed to have discovered a runestone near Kensington, MN in 1898, that he argued proved that the Vikings had reached Minnesota in 1362.

- While debate continues, it is unlikely that the runestone is authentic.

While Christopher Columbus became one of the most important figures in world history when he reached the Caribbean in 1492, he was not the first explorer from the East to arrive in the Americas. During the opening decades of the 11th century, Viking explorers sailing west from their settlements in Greenland reached the northeastern portions of present-day Canada. While Viking sagas

had long mentioned various accounts of short-lived Norse settlements in North America, it was not until the 1960s that archeological evidence corroborated Viking legends and provided convincing evidence. Today, historians and archaeologists agree that Viking explorers and settlers had established a small colony on the northernmost shore of Newfoundland, Canada, by 1021 CE that endured for some 15 years.

In 1898, long before scholars begrudgingly agreed that the Vikings had indeed beaten Columbus to the Americas, Olof Ohman and his 10-year-old son uncovered what they claimed was evidence that Norse explorers had found their way to Minnesota in 1362. As they worked to expand their farm field near Kensington, they claimed to have found a runestone, like ones Viking explorers had left in the British Isles and all over Europe, with an inscription that read:

We are eight Goths and 22 Norwegians on an exploration journey from Vineland through the West. We had a camp by a lake two days’ journey north from this stone. We were out and fished one day. After we came home we found 10 of our men red with blood and dead. AVM save us from evil. We have 10 of our party by the sea to look after our ships, 14 days’ journey from this island.[1]

Since Ohman shared the runestone with locals in nearby Alexandria a debate has been raging between those who believe it to be a relic left by a forgotten Viking incursion into the heart of the North American continent, and those who are convinced it is a hoax perpetuated by a late 19th-century Swedish immigrant with a sense of humor and an interest in his heritage. Defenders point to a 1354 order found in Scandinavian archives in which Norwegian Monarch Magnus Erickson ordered Baron Paul Knutson to travel to Greenland and re-establish contact with settlements that the king feared had “fallen away from the [Catholic] faith.” From there, generations of largely self-taught defenders weave an interesting theory that takes Erickson’s expedition from a four-year search of the St Lawrence Bay to Hudson Bay, up the Nelson River, through Lake Winnipeg, and finally up the Red River to the location of the runestone’s discovery near Kensington. The theory concludes by suggesting that the Norsemen eventually gave up their search and made their way further west into present-day North Dakota, where the Mandan people took them in.

Despite the passionate and enduring arguments supporting Ohman’s claim, academically trained historians, archaeologists, and linguists discount the runestone as a hoax. Noting that defenders continue to ignore historical context and selectively use evidence, they argue that the stone contains markings of a later era that were unknown in 1362. Historian William Lass summed up the detractors’ view, stating that there is “overwhelming evidence that the stone is a hoax,” and that the authenticity argument is only persuasive “for those unfamiliar with the nature of historical proof and hoaxes.”

Despite the stinging and consistent criticism, the stone continued to attract attention both within and beyond Minnesota. In 1948, the Smithsonian displayed the stone and announced that it was “probably the most important archeological object yet found in North America.” The following year, the stone returned to Alexandria and played a prominent role in the territorial (1949) and state (1958) centennial celebrations. By the late 1950s, it found a permanent home in Alexandria’s Runestone Museum, as its host city began referring to itself as “the Birthplace of America.” The debate continued to rage into the early 21st century, with defenders continuing to publish lengthy volumes advocating the stone’s authenticity. In 2003, defenders and detractors met at the first-ever joint conference at Fort Snelling that was cordial but settled little. Later that same year, the stone traveled to Europe for study and public display.

The Kensington Runestone

- The Kensington Runestone

- Olof Ohman (center) posed with the Kensington Runestone about 1929. Start Tribune File Photograph

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

The runestone debate has now raged for well over a century, and there is little to suggest consensus will be reached in the foreseeable future. So, for now, the Kensington Runestone will continue to capture the imagination of its defenders and the public and offer history students an interesting look at evidence-based historical research.

A Colonial Struggle for a Continent

Section Highlights

- European nations competed to control the land and resources of North America throughout the colonial period.

- For over 100 years, France claimed the western Great Lakes, including what would become Minnesota, as part of their North American empire.

- From 1634 to 1763, the French explored the Western Great Lakes and established a thriving fur trade.

- France lost their North American holdings to Great Britain in 1763. Soon after, in 1783, Great Britain lost its holdings south of Canada to the new United States of America.

Regardless of the extent of the Viking presence in North America, the contact was temporary and did not produce a long-lasting impact. Columbus’s 1492 voyage, on the other hand, established an ongoing connection between the continents that resulted in world-changing outcomes. Among the most devastating for the Americas was the depopulation of indigenous people resulting from the introduction of European diseases to the Americas. Populations across the Americas plummeted to unimaginable levels, falling by as much as 90% within decades of localized contact.

In the void left by these virgin-soil epidemics, European nations rushed to colonize and reap the benefits of newly discovered and now sparsely settled land. Spain, for whom Columbus sailed, spread across the Caribbean, Central America, the southern sections of North America, and the western portions of South America while yielding what would become Brazil to the Portuguese. Other European nations soon arrived to challenge Spain’s dominance. The French claimed Eastern Canada and moved through the Saint Lawrence Seaway, and down through the Ohio River Valley, to the lower portions of the Mississippi River, where it exited into the Gulf of Mexico. This French crescent pinned English colonial outposts, which sprouted up from New England down to Georgia, to the Atlantic Seaboard.

New France

After a failed 1560s effort to challenge Spain’s dominance in Florida, the French turned their attention to the fish and furs abundant in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in present-day northeastern Canada. Moving up the St Lawrence River, the French established Quebec in 1608 and Montreal in 1642 as hubs in the sprawling colony of New France. Reaching its height in the early 1700s, the French North American Empire claimed the heart of the North American continent, stretching from Newfoundland in the north to the Canadian Prairie region in the west, to the Gulf of Mexico in the south. These claims included the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys, along with the Great Lakes Region, including what would one day become Minnesota. But New France was an empire in name only. The growing British colonies along the Atlantic seaboard and the massive Spanish populations in Central and South America dwarfed its sparse population. Initially dependent on North Atlantic fisheries, the economic engine of the colony became the fur trade, and by the middle of the 17th century, Montreal emerged as a trading hub.

From the early exploration phase beginning in the 1530s, to its height in the early 1700s, to its ultimate demise in 1763, New France’s economic viability and very existence were tied to its partnership with the Huron, Ottawa, Ojibwe, and other indigenous nations. The French provided sought-after trade goods, including arms, to their indigenous allies and assisted them in their ongoing feud with the powerful Iroquois to the south. In return, the allies hunted fur-bearing animals, provided military assistance, and tolerated French Catholic missionary efforts. Maintaining and extending this relationship was of paramount importance to the success of New France.

Initially under the able leadership of Samuel de Champlain (1574-1635), and later under the administration of Jean Talon (1626-1694), New France sent explorers west from Montreal in hopes of extending its fur trading network, converting indigenous people to Catholicism, and finding a water-route to the Pacific Ocean. Minnesota’s location at the western edge of the Great Lakes and that it encompassed the origin of the Mississippi River drew French interest and the first Europeans to the region.

French Exploration, 1634-1763

The fortunes of early New France fell on the shoulders of Samuel de Champlain, who spent over three decades of his life working to expand the trading network of the colony and discover a water route through North America. Traveling west from Quebec with the assistance of indigenous guides, Champlain had reached the Huron and Ontario Lakes, “discovering” them for France in 1615. During the 1630s, rumors again swirled suggesting major rivers flowed to a southern sea. Too old and ill to undertake any additional voyages of discovery, Champlain sent Jean Nicolet, who traveled south and west into present-day Wisconsin, where he met the Ho-Chunk people at Green Bay in 1634. Later that year, Champlain died, and the Company of New France struggled with rivals, Iroquois hostility, debts, and unlicensed traders. It largely abandoned sanctioned exploration for two decades.

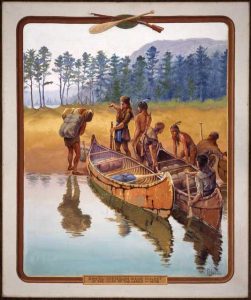

Two of the most well-known of these renegade (or unlicensed) traders were Pierre Esprit Radisson

and Medard Chouart des Groseilliers. Although not sanctioned by the New France Company, and therefore operating illegally, they made two important expeditions. In 1654, des Groseilliers moved through Lake Huron and Lake Michigan, and five years later, in 1659, the two jointly led an expedition of 30 Frenchmen and a larger group of Huron and Ottawa guides that took them along the shores of Lake Superior. The expedition brought them into contact with the Dakota in what would become Minnesota. Importantly, Radisson spent six weeks living with the Dakota at Lake Mille Lacs and made notes of their culture and practices.

Historian Mary Wingerd, however, reminds us that the two were likely not the first Europeans to reach Minnesota, stating, “Some 200 illegal traders are estimated to have worked the Northwest before Radisson and Groseilliers set out on their historic travels.” Regardless, this expedition is notable because it resulted in the earliest European account, as biased and exaggerated as it was, of the Dakota and the region’s geography. The importance was not lost on Radisson, who hoped to profit from his exploits when he wrote: “We are Caesars, being nobody to contradict us.”[2]

Believing that they would be forgiven for unlicensed trading when they returned with vast knowledge of the region and piles of furs, Radisson and Groseilliers were surprised to be detained, sanctioned, and stripped of their furs. Once released, they both left North America, made their way to England, and played an important role in the development of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Ironically, the formation of the Hudson’s Bay Company immediately spurred administrators in New France to quicken the pace of exploration. Later, the company proved instrumental in the French downfall in North America.

New France continued to struggle, and in 1663, Louis XIV converted it into a royal colony and appointed able administrators to revive the enterprise. Spurred by news of the organization of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670, Jean Talon launched a renewed effort to explore the Great Lakes region and extend the colony’s trading network. In 1673, a Jesuit Priest, Jacques Marquette, and the philosophy student-turned-fur-trader, Louis Joliet, traveled the Fox River and then the Wisconsin River to where it met the Mississippi River just south of present-day Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. They then travel down the Mississippi to the confluence of the Arkansas River before returning via the Chicago and Illinois Rivers and famously camping at the future site of Chicago. While they were saddened to realize that the Mississippi led south and not west, they did note the Missouri River converging from the west, and identified a southern route into Minnesota (traveling up the Mississippi), to complement the northern route through Lake Superior.

Before the decade was out, the first sanctioned delegation from New France reached Minnesota. In 1678, Montreal and Quebec traders sent Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut

to the western shore of Lake Superior in an effort to revive the stagnated fur trade. He and his small party accompanied a delegation of Ojibwe from Sault St. Marie to the present-day city that bears his name and traveled with them to the principal Dakota village at Mille Lacs. Du Lhut was witness to negotiations that brokered a peace between the Ojibwe, then just entering the region, and the Dakota that would benefit not only the two indigenous nations but also the French by stimulating a collaborative fur trade. The peace lasted for the most part into the 1730s. Before Du Lhut departed, he conducted an elaborate ceremony formally claiming the territory for his king. Regardless of the gesture, the French were visitors in the region, allowed to move freely only due to the goodwill of the Dakota and Ojibwe.

The following summer, Du Lhut learned of three captives held by the Dakota and, according to his telling, was able to arrange their release. The three were a detachment sent from an expedition led by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, then at the mouth of the Illinois River. They were sent north to investigate the upper regions of the Mississippi while the rest of the expedition traveled south. After spending two months struggling against the current and moving up the Mississippi, they were overtaken by a Dakota hunting party, and, either as captives or honored guests, brought to Lake Mille Lacs. Regardless of their status, Du Lhut’s account of his role in their “release” is most certainly exaggerated. Upon hearing of Du Lhut’s account, his rival La Salle lamented, “he will not fail to exaggerate everything… He speaks more in keeping with what he wishes than what he knows.”[3]

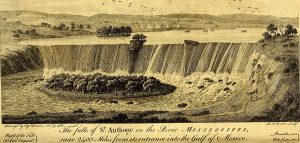

Belgian Father Louis Hennepinwas the diarist and cartographer for the “captured” detachment. After his release, Hennepin returned to Europe in 1683 and published Descriptions of Louisiana, the first book describing Minnesota to curious European readers. Hennepin emphasized the things he thought would interest his readers, and he embellished – if not outright concocted – many aspects of his account. Among the places he described, Hennepin recalled the northernmost waterfall on the upper Mississippi. While with the Dakota, he was taken by the waterfall that he named after his patron saint, Anthony of Padua. The falls had for generations been a spiritually important place for the Dakota, and so too would they become important for traders and the eventual Euro-American settlers. Today, the Falls of St. Anthony are surrounded by Minneapolis – a city they helped build.

By the 1680s, exploration began to give way to the establishment of an ongoing French fur trading presence. Nicolas Perot established fur trading posts in Minnesota – one near present-day Duluth and another on the Wisconsin side of Lake Pepin. One of his Lieutenants, Pierre Charles Le Sueur, reached Minnesota in 1700 by traveling up the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico and established a fur trading post on the Blue Earth River under the guise of mining copper from the region. Le Sueur was the first explorer of the Minnesota and the Blue Earth rivers, and the county bears his name today.

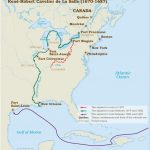

French Exploration

- Jean Nicollet Exploration Route, 1634.

- Radisson and Groseillers exploration route, 1659-1660.

- Marquette and Jolliet Exploration Route, 1673-1694.

- Sieur de La Salle Exploration Route, 1670-1687.

These maps are from the Virtual Museum of New France. For interactive maps and fuller descriptions of these journeys of exploration, visit: Virtual Museum of New France: The Explorers

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

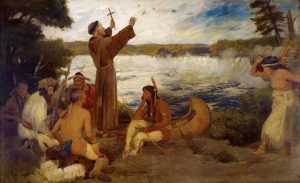

Father Hennepin Discovering the Falls of St. Anthony

This controversial 1905 painting by Stephen A. Douglas Volk is the painter’s imagined portrayal of Father Louis Hennepin preaching to Dakota people at the Falls of St Anthony in 1680. For many years, it hung in the Governor’s Reception Room at the Minnesota State Capitol, where countless Minnesotans viewed it without any historical context. The scene the image presents is an inaccurate view of history and is offensive to some in its depiction of the Dakota. The painting has since been moved to a gallery inside the capital that allows for interpretation that provides historical context for the image. Take some time to view the image and watch the commentary below. What are your thoughts about the painting and the Minnesota Historical Society’s decision to remove the image from the reception room but keep it displayed in a separate gallery?

Wars for Empire

The French successful attempts to explore, claim, and establish the fur trade in Minnesota played out in the context of a wider struggle for control of North America. Europeans engaged in five conflicts that historians sometimes call the Great Wars for Empire. The first four conflicts started in Europe or the Caribbean and expanded to include a theater of operation in North America, which saw each empire’s colonial populations engage each other, along with the assistance of their respective indigenous allies. With two notable exceptions, the peace treaties of these various conflicts left the North American map unchanged. The first exception occurred at the end of Queen Anne’s War in 1713, which saw the Hudson Bay region pass from French to British control. This change made room for the British fur trade to flourish in the region as administered by the Hudson Bay Company, and the French to work to draw the fur trade further south into regions they still controlled.

|

The Great Wars for Empire

|

The fifth and final War for Empire was the second exception and proved critical in the history of North America. Unlike all the conflicts that preceded it, the French and Indian War began in the Ohio River Valley as a skirmish between British and French colonists and grew into a world war. Although the French, aided by their indigenous allies, ran up early victories, massive British investment proved too overwhelming, and they were forced to surrender the entirety of New France in 1763. This British victory remade the European map of North America. Land east of the Mississippi River passed to the British while lands west of the Mississippi River passed – although in name only – to the Spanish. As a result, parts of Minnesota east of the Mississippi River were now claimed by the British, while land to the west of the river was technically part of the Spanish North American empire.

The peace that concluded the French and Indian War ended the era of French-sponsored exploration and their control of the fur trade in the western portions of the Great Lakes region. In doing so, it ended over 100 years of exploration and trade development. During that extended period, the French had accomplished much, including mapping much of the area, developing a thriving fur trade, discovering numerous waterways, establishing the French language as the standard for trade in the region, and placing French traders in the area who would remain after France lost political control of the region.

British Period 1763-1783

The British total victory in the French and Indian War proved short-lived. Acquiring a huge swath of land from former French holdings brought administrative burdens, conflicts with indigenous peoples used to the more collaborative relationships they had with the French, and an unsettled colonial population pushing to expand into indigenous lands. British administration of the territory began with a devastating and brutal war with an indigenous confederation led by the Ottawa leader Pontiac and others. It concluded with the loss of its holdings south of present-day Canada to its colonists in 1783.

Given the chaotic and brief period in which Great Britain claimed the eastern portion of Minnesota, the legacy of British-led exploration paled in comparison to the French period that preceded it. One expedition, marred in controversy, did, however, result in the publication of Jonathan Carver’s Travels Through the Interior Parts of North America: 1766, 1767, 1768. Born in colonial New England, Carver served in the French and Indian War before signing on as a map maker for an expedition intent on discovering a passage to the Pacific Ocean through the northwest region of the continent. Unbeknownst to Carver, the expedition was unsanctioned and ended in its leader’s arrest. Regardless, during the winter of 1766 and 1767, Carver, detached from the main exploratory party, wintered with the Dakota along the Minnesota River. He later converted his journals into a book published in 1778 that unfortunately included long sections of plagiarized text added by the editor. Even still, the book endured challenges to its authenticity and went through 16 editions in just 20 years after its initial publication. For all its shortcomings, it was the first English-language book of its kind and did document the time Carver spent with the Dakota in Minnesota.

Conclusion

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Columbus’s journey to the Caribbean in 1492 and the impact it had moving forward in world history. Reverberations impacted Minnesota as they did nearly everywhere else. While France, Spain, and Great Britain claimed all or parts of the area that would become Minnesota at various times, only France and Great Britain attempted to develop a presence in the area. Early European explorers and traders, mostly French Canadians, paved the way for the development of the fur trade, which came to dominate European-indigenous interaction through the 17th and 18th centuries.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Backerud, Thomas. “Radisson, Pierre Esprit (1636/1640–1710).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/radisson-pierre-esprit-16361640-1710 (accessed February 22, 2018).

Backerud, Thomas. “Greysolon, Daniel, Sieur du Lhut (c.1639–1710).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/greysolon-daniel-sieur-du-lhut-c1639-1710 (accessed February 22, 2018).

Gilman, Rhoda R. “Kensington Runestone Revisited: Recent Development, Recent Publication,” Minnesota History, Summer 2006. pp. 61-65.

Gould, Heidi. “Carver, Jonathan (1710–1780).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/carver-jonathan-1710-1780 (accessed February 22, 2018).

Goetz, Kathryn. “Hennepin, Louis (ca.1640–ca.1701).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/hennepin-louis-ca1640-ca1701 (accessed February 22, 2018).

Holand, Hjalmar R. “Concerning the Kensington Rune Stone,” Minnesota History, June, 1936. pp. 166-88.

Lass, William. Minnesota: A History. 2nd Ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1998.

Wingerd, Mary Lethert. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

- Rhoda R Gilman, “Kensington Runestone Revisited: Recent Developments, Recent Publication.” Minnesota History, Summer 2006, pp. 61-62; William Lass. Minnesota: A History, 2nd Edition. (New York: Norton and Company, 1998), 48. ↵

- Lass, Minnesota: A History, 56-57; Wingerd, North Country, 6-9; Backerud, Thomas. "Radisson, Pierre Esprit (1636/1640–1710)." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/radisson-pierre-esprit-16361640-1710 (accessed April 8, 2018). ↵

- Lass, Minnesota: A History, 58-59; Wingerd, North Country, 18-19; Backerud, Thomas. "Greysolon, Daniel, Sieur du Lhut (c.1639–1710)." MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/greysolon-daniel-sieur-du-lhut-c1639-1710 (accessed April 8, 2018). ↵

The Old Norse word saga means 'story', 'tale' or 'history' and normally refers specifically to the epic prose narratives written mainly in Iceland between the 12th- and 15th centuries CE, covering the country's history as well as Scandinavia's legendary past. A few sagas were also written in Norway but in either country their usually anonymous writers shaped their stories in high-quality, nuanced prose, leading the saga to now be considered one of the prime vernacular literary genres of Medieval Europe.

Emma Groeneveld, World History Encyclopedia - https://www.worldhistory.org/Saga/

The Kensington Runestone is a gravestone-sized slab of hard, gray sandstone called graywacke into which Scandinavian runes are cut. It stands on display in Alexandria, Minnesota, as a unique record of either Norse exploration of North America or Minnesota’s most brilliant and durable hoax.

Paul Nelson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/kensington-runestone

Pierre Esprit Radisson’s 1659 expedition to Lake Superior and beyond opened a door to the North American fur trade. Through it, he earned a reputation as a courageous explorer and a cunning merchant. In the 2010s he is remembered as one of the first Europeans to travel to what became the state of Minnesota.

Thomas Backenrud, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/radisson-pierre-esprit-16361640-1710

Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut (also known as du Luth), was born in Lyons, France, around 1639. A nobleman who quickly rose to prominence in the French royal court, he traveled to New France (Quebec, Canada) in 1674 at the age of thirty-eight to command the French marines in Montreal.

Thomas Backenrud, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/greysolon-daniel-sieur-du-lhut-c1639-1710

Father Louis Hennepin, a Recollect friar, is best known for his early expeditions of what would become the state of Minnesota. He gained fame in the seventeenth century with the publication of his dramatic stories in the territory. Although Father Hennepin spent only a few months in Minnesota, his influence is undeniable. While his widely read travel accounts were more fiction than fact, they allowed him to leave a lasting mark on the state.

Kathryn Goetz, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/hennepin-louis-ca1640-ca1701

Jonathan Carver was an explorer, mapmaker, author, and subject of controversy. He was among the first white men to explore and map areas of Minnesota, including what later became Carver County. While French explorers had been in the area earlier, they did not leave behind detailed maps or journals of their travels as Carver did.

Heidi Gould, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/carver-jonathan-1710-1780