3 Early Minnesotans: The Dakota and Ojibwe

Before Columbus’s 1492 voyage, the Western Hemisphere was home to perhaps 50 million people. Massive cities had long existed in Central and South America, and portions of current-day Mexico were among the most densely populated places in the world. North of Mexico, between five and ten million people lived in diverse and less densely settled communities that spread north to the Arctic and touched both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Five hundred distinct indigenous nations thrived and spoke as many as 300 different languages.

While indigenous nations were each distinct with their own histories, religious beliefs, customs, and cultures, some general similarities existed and differentiated indigenous culture from that of the arriving Europeans. Perhaps most notable was how each group understood its relationship with the environment. Many indigenous people saw themselves as part of their landscape. Minnesota Ojibwe historian, Winona LaDuke explained, “with our native traditions there is this immense ethic, this minibimaatisiiwin, this way that you live… which has something to do with the continuity of living in one place, of observing intergenerationally the changes on land and the behavior of all of your relatives that are four-legged and two-legged and trees and winged. You are very cognizant of your behavior as a part of a whole and the ramifications of your behavior in that bigger picture, and that if you’re going to live there for 10,000 years, you better figure that out.”[1]

Conversely, Europeans saw themselves as separate and above the landscape they encountered in North America. They followed the instructions provided in the first book of the Christian bible, where people were told to “be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.” Not only did these different perspectives cause continual misunderstandings, but they also impacted the landscape differently.

Closely related to the different perspectives regarding where people fit into the landscape was a disconnect regarding the concept of land ownership. Indigenous people believed in territorial occupancy and fought wars over access to land. Importantly, however, they did not see the land as something that could be owned by individuals. Europeans and later Euro-Americans brought the opposite understanding and saw land as perhaps the most important thing someone could own. These different perspectives later played a central role in a long and painful history of treaty making and land dispossession in and beyond Minnesota.

By the time Columbus arrived in the Caribbean in the late 1400s, Dakota people had been living in what would become Minnesota for countless generations. By the middle of the 1600s, European colonies had developed along the Atlantic seaboard, and the first explorers and traders began to reach the western edge of the Great Lakes. About the same time, the Ojibwe people neared the end of their generations-long migration that brought them into present-day Minnesota from the east. The Dakota and the Ojibwe have long histories of interacting with each other and in navigating the changes brought by the arriving Europeans and later the development of Euro-American communities. Before extensive European contact, they shared similar lifeways and perspectives that allowed them to live in unison with their surroundings.

The Dakota Oyate

Section Highlights

- The Dakota people have been in Minnesota the longest and teach that they originated here.

- The Dakota Oyate (Nation) is organized into seven Council Fires.

- The Dakota have been known by other names, including Sioux.

- Prior to reservation life, the Dakota lived lives closely connected to the land and moved with the seasons.

Of all the groups of people living in Minnesota, people belonging to the Dakota Oyate (Dakota Nation) have been here the longest. While not undisputed, many Dakota accounts trace their origin to Minnesota. According to Erin Griffin, a social anthropologist and member of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota, “claims of Dakota origins in places other than Mni Sota Makoce conflict with Dakota oral narratives and ultimately undermine Dakota connection to the land.” She explains, “We are told that we were brought here to this land from the stars to the places where the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers meet. This place, known as Bdote, is our place of genesis. We recognize Bdote as the center of the earth and all things…”[2]

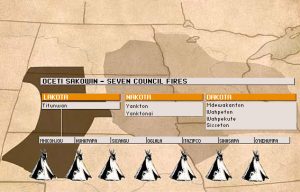

From this place of origin, the Dakota spread to cover a huge swath of land in the upper Midwest that includes the present-day states of Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota, along with eastern sections of Wyoming and Montana. The Dakota Oyate is organized into seven council fires based on location. Four of the council fires – Mdewakanton, Sisseton, Wahpekute, and Wahpeton – speak the Dakota dialect and are located in Minnesota. To the west, mostly in North and South Dakota, the Yanktonai and Yankton speak the Nakota dialect. Even further west, reaching into present-day Wyoming and Montana, the Teton speak the Lakota dialect.

| Dialect | Name | Meaning | ||

| Dakota | Mdewakanton | The spiritual people who live by water | ||

| Sisseton | The medicine people who live by water | |||

| Wahpekute | Warriors who protected the medicine people and could shoot from among the leaves | |||

| Wahpeton | The people who live in the forest | |||

| Nakota | Yanktonai | Those scattered at the edge of the forest | ||

| Yankton | The people who live at the edge of the great forest | |||

|

Lakota |

Teton |

Dwellers of the plains |

Previously, and at times still today, the Dakota Oyate is sometimes called the Great Sioux Nation. This name refers to the three branches or dialects and the seven council fires discussed above. Although the Dakota Oyate and the Great Sioux Nation refer to the same people, the connotations of the names differ. The word Sioux is derived from a European shortening and mispronunciation of an Ojibwe word, nadowe-is-iw-ug, meaning snake. The Ojibwe used this term to describe the Dakota people during a period of conflict between the two nations. The word Dakota is a name used by the Dakota people themselves that translates to friend or ally. Given this history, the name Sioux has been controversial, and many Dakota prefer it not be used in identifying their people. This controversy continues into our own time, most notably when the University of North Dakota changed its nickname from the Fighting Sioux to the Fighting Hawks in 2015. Some Dakota people saw the Fighting Sioux nickname and mascot as an honor and source of pride, while others found it insensitive and offensive. As a result of this controversy, the University made the name change, as have other college and professional sports teams recently. It is also important to note that during the 19th century, the US government often used Sioux to refer to the Dakota, and that name is used consistently in treaties. Other names for the Dakota people utilized by U.S. government documents include Minnesota Sioux, Sioux of the Mississippi, Eastern Sioux, Santee Sioux, and Santee.

Dakota Oyate – Seven Council Fires

Prior to extensive European contact, the Dakota people lived lives closely connected with the land. They moved with the seasons and adapted to their environments, meaning life for the Dakota-speaking people living in the wooded areas of Minnesota was a bit different than it was for the Lakota-speaking people living on the prairies to the west. Regardless of location, all Dakota people moved with the seasons. In Minnesota, the spring saw people leave their winter quarters – men moved into hunting camps while women and children established sugar camps where they tapped sap from trees to boil down to be used as a syrup and a sweetener. In the summers, people moved into their permanent settlements, often near lakes or rivers, cultivating corn, beans, and squash, while also hunting and fishing. In the late summer and into early fall, family groups collected and processed wild rice from the shallow waters in northern Minnesota. As fall turned colder, smaller extended-family groups established mobile camps – men hunted and women moved the lodges and prepared food. Winter, the most difficult of the seasons, saw people spread out into smaller groups – mending clothes, subsisting on food gathered during the summer and fall, hunting, and fishing through the ice.

Wild Ricing

Arrival of the Ojibwe

Section Highlights

- The Ojibwe share many similarities with the Dakota, including a traditional culture of moving with the seasons.

- The Ojibwe are sometimes called the Anishinaabe today and were referred to as Chippewa in 19th-century US government documents.

- After a centuries-long migration, Ojibwe people arrived in what would become Minnesota during the 17th century.

- The Ojibwe played an important, middleman role in the fur trade that brought trade goods to the Dakota.

- The peaceful coexistence of Ojibwe and Dakota in Minnesota was interrupted by a war between 1739 and the early 1800s.

The Ojibwe, who arrived in the western portions of the Great Lakes in the middle of the 1600s, share many similarities with the Dakota – they too were descendants of Woodland cultures, moved with the seasons, harvested wild rice, and made sugar from maple tree sap. There were important differences as well – the Ojibwa spoke a different language, held different origin stories, and religious beliefs. They built wigwams (dome-shaped lodges covered with bark), while the Dakota lived in earthen lodges and used teepees while on the move. The Ojibwe birchbark canoes also differed from the Dakota preference for hollowed-out log canoes. Upon the arrival of the Ojibwe in the area, the two nations began a long and dynamic relationship that continues to this day.

Like the Dakota, the Ojibwe have been known by a variety of names over the centuries. The word Ojibwe (sometimes spelled Ojibwa or even Ojibway) is an Ojibwe word whose origin is most likely connected to the puckered seam of a traditional Ojibwe moccasin (shoe), or it could also refer to the Ojibwe practice of writing on birch bark. Either way, the Ojibwe people use the term Ojibwe to differentiate themselves from other indigenous groups. Sometimes the Ojibwe are referred to as Anishinaabe – a term the Ojibwe often use to identify indigenous peoples in general. Finally, the word Chippewa had been commonly used by Europeans and later the United States Government to denote the Ojibwe people. The term Chippewa was used consistently in 19th-century US government documents and treaties, but since it is mostly a mispronunciation of the word Ojibwe, it is little used today.

Source: Dave Kenney, Northern Lights: The Stories of Minnesota’s Past (St. Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society, 2013), 53.

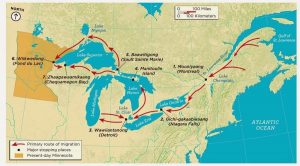

Originally, Ojibwe ancestors were part of the larger group of Algonquian-speaking people settled along the eastern seaboard in what is today the northeastern sections of the United States and eastern Canada. Around 500 CE, the Ojibwe began to distinguish themselves as a separate subgroup within the Algonquian linguistic grouping as they made their first steps in what became a centuries-long migration. Following the urging of prophets, the Ojibwe traveled in small groups along the St Lawrence Seaway and eventually into the Great Lakes region. By the early 1700s, they began entering what would become northern Minnesota. As the prophet had foretold, the Ojibwe knew they had reached the end of their journey when they found wild rice, food growing on the water.

During their migration, the Ojibwe had developed and maintained a close connection with French fur traders. As they moved west, they became the conduit in a Great Lakes fur trading network that exchanged furs from the interior for European goods such as kettles, knives, traps, tools, beads, cloth, and guns. This connection proved crucial as the Ojibwe entered Dakota homelands. In 1679, the Dakota met with the Ojibwe at Fond Du Lac in present-day Minnesota and negotiated an arrangement that allowed the Ojibwe access to Dakota lands west of the Mississippi in exchange for Dakota access to French trade goods provided through Ojibwe middlemen. The mutually beneficial arrangement not only brought economic prosperity to both nations, but it also included ongoing cultural exchanges and extensive intermarriages. This collaboration endured for 57 years.

Mille Lacs Indian Museum and Trading Post

Longtime friends turned enemies in 1739 after the son of a French explorer was killed in a skirmish between a joint French, Cree, and Assiniboine party and an allied force of Dakota and Ojibwe near Rainy Lake in northern Minnesota. Although both the Ojibwe and the Dakota had been involved in the conflict that led to the death, the French held the Dakota solely responsible and armed for retribution. The Ojibwe were then forced to choose between their friendship with the Dakota and their economic relationship with the French. They chose the latter, and an extended period of bloody conflict ensued between the former allies. The Ojibwe and Dakota fought Pitched battles at Sandy Lake (1744), Mille Lacs (1745), on the St Croix River (1755), at Leech Lake (1760), and Red Lake (1770). By the 1770s, Ojibwe access to French weaponry and trade goods helped them push the Dakota south, and the intensity of the ongoing conflict lessened. Intermittent, low-level fighting continued into the 19th century when the pressure brought by Euro-American settlement eclipsed the conflict, and the nations slowly settled their differences.

Ojibwe Seasonal Cycle

Like the Dakota, the Ojibwe moved with the seasons. The images below are from the Four Seasons Room at the Mille Lacs Indian Museum.

- Spring

- Summer

- Fall

- Winter

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book. Photograph by Aaron Bommarito December, 2021.

From Storytelling to Written History

Section Highlights

- Like most American Indian nations, the Dakota and Ojibwe recorded their past by passing down oral stories to younger generations.

- The first written accounts of Dakota and Ojibwe lifeways were recorded by European men and reflected their worldview.

- William Warren (1825-1853), a person of mixed French and Ojibwe heritage, wrote the first history of the Ojibwe people that used Ojibwe oral stories as sources.

- Charles Eastman (1858-1939) published 11 books about Dakota culture and his life experiences.

Like most American Indian nations, prior to extensive European contact, both the Dakota and Ojibwe passed along their history and culture to younger generations through spoken stories. While this tradition continues to this day, European contact has resulted in adding a written record to this process as well. Many early written sources about the Dakota and Ojibwa came from European men and were presented through their life experiences and worldviews. Adding a different perspective to this narrow viewpoint came 19th-century authors of mixed European and indigenous heritage. Two Minnesota scholars who provided insight into the traditional indigenous lifeways were William Warren, who was part Ojibwe, and Charles Eastman, who was part Dakota.

Both Warren and Eastman had been raised in traditions of their indigenous families but had received formal schooling in the Euro-American tradition. Their very existence is evidence of the massive changes European contact brought. They were each intimately connected to both traditions, and their scholarship provided important insights into their respective pre-contact cultures.

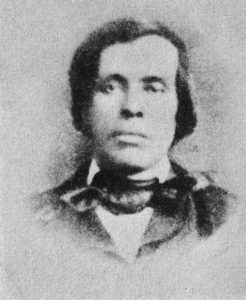

William Warren

William Warren was born in 1825 to an Ojibwe-French mother and a Euro-American father in La Pointe on Madeline Island near the western shore of Lake Superior (part of Wisconsin today). He spent his early childhood learning the language and customs of his mother’s people, but later was educated in the traditions of his father, first at mission schools on Mackinac Island and then at La Point before continuing in New York at Clarkson Academy. His connection to both cultures and his fluency in both languages led to employment as a government and private interpreter and to a stint in the Minnesota Territorial legislature. As a teenager, he began to collect stories from Ojibwe elders and eventually incorporated them into the first written history of the Ojibwe people. Sadly, in 1853, he died as a young man of just 28 before publishing his history or pursuing his vision of continuing his life’s work. His book, The History of the Ojibway People, Based Upon Traditions and Oral Statements, was eventually published in 1885 by the Minnesota Historical Society. One of its kind, the work continues to be important and is recognized as, in the words of Theresa Schenck, “a seminal work in Ojibwe history, it stands alone, a monument to the author’s knowledge and love of his grandmother’s people.”[3]

Warren understood that he was in a unique position to write the first account of Ojibwe history, given his connection to Ojibwe culture and his Western education. He also understood, as did others, that it was important to undertake the writing at a time when Euro-American contact was changing how the Ojibwe lived. In doing so, he converted oral storytelling to written history – a difficult task he did not complete without oversights – but one he did complete. When discussing his project with Buffalo, his grandmother’s cousin, the elder Ojibwe agreed to help him with his task and seemed to understand its importance, telling Warren: “You are now a man, you know how to write like the whites, you understand what we tell you. Your ears are open to our words, and we will tell you what we know of former times. You shall write it on paper that our words may last forever.”[4]

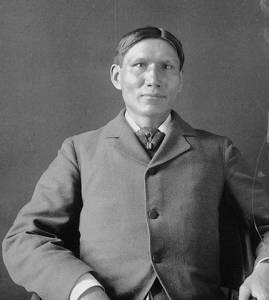

Charles Eastman

Charles Eastman was born to Dakota parents on the Lower Sioux Reservation near present-day Redwood Falls, MN, in 1858, five years after Warren’s untimely death. Unlike Warren, he spent his earliest years on a reservation. His mother died shortly after his birth. At the age of four, he was separated from his father and siblings as his community fled to Canada in the wake of the US Dakota War of 1862. His extended family raised him along traditional Dakota customs until the age of 15, when he was reunited with his father, who had by then converted to Christianity. Reluctantly at first, Eastman also converted to Christianity and began attending a mission day school. He continued his education by attending Beloit College and then Knox College before graduating from Dartmouth in 1887. Three years later, in 1890, he became one of the first indigenous person to earn a Western medical degree. Upon earning his medical degree from Boston University, Eastman returned to the Midwest and served as an Indian Agency physician on Dakota reservations in South Dakota. Still a new doctor, he attended to the wounded Dakota brought into the Pine Ridge Reservation from the Wounded Knee Massacre in December of 1890.

With the assistance of his wife, Elaine Goodale, he authored 11 books focusing on Dakota culture and his life experiences. Perhaps among the most important contributions these books provide are the presentation of Dakota traditional customs, beliefs, and lifeways. Eastman himself understood the importance of his efforts, stating: “I have attempted to paint the religious life of the typical American Indian as it was before he knew the white man. I have long wished to do this, because I cannot find that it has ever been seriously, adequately, and sincerely done.”[5] His writings, like Warren’s, provide a window into traditional indigenous customs and storytelling from the perspective of someone raised in those traditions.

Conclusion

The Dakota people have called Minnesota home longer than any other group. Toward the end of the 17th century, they were joined here by the Ojibwe, who were finishing a centuries-long migration that brought them west from the Northeastern Atlantic seaboard. Together, they navigated the rapid change brought by European exploration and trade and later the establishment of Euro-American communities. Today, both the Dakota and Ojibwe remain a vibrant part of Minnesota. What happened between the first European contact in the area and today is of critical importance in understanding our shared history.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Eastman, Charles, and Michael Oren Fitzgerald. The Essential Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa): Light on the Indian World. Lanham: World Wisdom, 2010.

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2009.

Peacock, Thomas. “The Ojibwe: Our Historical Role in Influencing Contemporary Minnesota.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/ojibwe-our-historical-role-influencing-contemporary-minnesota (accessed December 10, 2021).

Teresa Peterson and Walter LaBatte Jr.. “The Land, Water, and Language of the Dakota, Minnesota’s First People.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/land-water-and-language-dakota-minnesota-s-first-people (accessed December 10, 2021).

Treuer, Anton. Ojibwe In Minnesota. The People of Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010

Warren, William W., and Theresa M. Schenck. History of the Ojibway People. 2nd edition. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2009.

Westerman, Gwen and Bruce White. Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012

- Minnesota: A History of the Land, “Episode 1: Ordering the Land.” DVD. St. Paul, MN: College of Natural Resources – University of Minnesota; Twin Cities Public Television, 2005. ↵

- Westerman, Gwen and Bruce White, Mni Sota Makoce: Land of the Dakota (St. Paul, Minn: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012), 15, 231-32. ↵

- Warren, William, A History of the Ojibway People. Second edition edited and annotated with a new introduction by Theresa Schenck. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1885, new material 2009, 35. ↵

- Warren, A History of the Ojibway People, 15. ↵

- Eastman, Charles. Fitzgerald, Michael. Ed. The Essential Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa). Ed. Michael Fitzgerald. (Bloomington, IND: World Wisdom, 2007), xii. ↵

The footprint of the Dakota people, past and present, is evident throughout Minnesota. Mni Sota Makoce, the land of cloudy waters, has been the homeland of the Dakota for hundreds of years. According to the Bdewakantonwan Dakota creation story, Dakota people and life began in Minnesota, and despite a tumultuous history, they continue to claim this land as their home.

Teresa Peterson and Walter LaBatte Jr., MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/land-water-and-language-dakota-minnesota-s-first-people

When I think about how the Ojibwe have helped shape this great state, I tend to separate the ways we have influenced the land from the ways we have influenced its people.

Thomas Peacock, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/ojibwe-our-historical-role-influencing-contemporary-minnesota

Wild rice is a food of great historical, spiritual, and cultural importance for the Ojibwe people. After colonization disrupted their traditional food system, however, they could no longer depend on stores of wild rice for food all year round. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, this traditional staple was appropriated by white entrepreneurs and marketed as a gourmet commodity. Native and non-Native people alike began to harvest rice to sell it for cash, threatening the health of the natural stands of the crop. This lucrative market paved the way for domestication of the plant, and farmers began cultivating it in paddies in the late 1960s. In the twenty-first century, many Ojibwe and other Native people are fighting to sustain the hand-harvested wild rice tradition and to protect wild rice beds.

Jessica Milgroom, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/wild-rice-and-ojibwe

The North American fur trade began around 1500 off the coast of Newfoundland and became one of the most powerful industries in US history. In Minnesota country, the Dakota and the Ojibwe traded in alliance with the French from the 1600s until the 1730s, when Ojibwe warriors began to drive the Dakota from their homes in the Mississippi Headwaters region. Afterward, the Dakota continued trading in the south while Montreal traders and their Ojibwe allies established a network of trading posts in the north. For the next 120 years, the fur trade dominated the region’s economy and contributed to the development of a unique multicultural society.

Jon Lurie, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/fur-trade-minnesota

Famed author and lecturer Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa) was raised in a traditional Dakota manner until age fifteen, when he entered Euro-American culture at his father's request. He spent the rest of his life moving between Native American and settler-colonist worlds, achieving renown but never financial security.

Molly Huber, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/person/eastman-charles-alexander-ohiyesa-1858-1939