2 Place and People: Geography and Prehistory

Minnesotans have always had a close relationship with their surroundings. While this is most probably true of people in all places, our history suggests that in Minnesota this relationship is perhaps more pronounced. This connection can be seen in what we call things. Minnesota, for example, the name for the state and one of the state’s major rivers is derived from the Dakota word Mni Sota Makoce, which roughly translates to “cloudy, muddy, or sky-tinted water,” or “land where the waters reflect the sky.” For many Minnesotans, place is top-of-mind – it drives our history and helps define our culture.

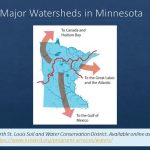

Situated near the center of the North American Continent, and at the elbow of navigable waterways running east from the Atlantic Ocean and south to the Gulf of Mexico, Minnesota’s location in relation to land and water helps make this connection enduring. Tall and skinny, the state borders the greatest of the Great Lakes, Lake Superior, and is the origin point of the continent’s mightiest river, the Mississippi. The state is also located at the junction point of three continental ecological systems (or biomes) and sits on the seam of three watersheds that send Minnesota water running in three different directions.

Ancient and massive glaciers carved the state’s landscape and left in their wakes rolling hills, rocky cliffs, fertile prairies, an extensive network of rivers, and over 15,000 lakes. As soon as the glaciers finished their work, prehistoric peoples inhabited this place and began a story of human interaction that was both driven by Minnesota’s environment and fundamentally altered that environment.

Place

Section Highlights

- Thousands of years ago, Minnesota’s landscape was formed by glaciers.

- Minnesota is located near the center of North America and is the meeting point of continental biomes and watersheds.

- Minnesota’s network of rivers complements the layout of its biomes and watersheds.

- Minnesotans continue to struggle with preserving their environment while providing opportunities to make a living from it.

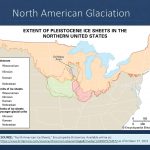

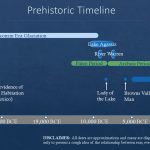

Beginning over two million years ago, the Nebraskan Ice Stage (2,000,000 BCE), the Kansan Ice Stage (400,000 BCE), and the Illinoian Ice Stage (150,000 BCE) sent successive sheets of glacial ice south from Canada that advanced and retreated across what would become Minnesota. The weight of these ice sheets gouged the landscape and, in their retreats, scattered massive amounts of glacial till. Over these millions of years, all of Minnesota, except for a small section in the southeasternmost part of the state (known as the Driftless area), was covered in glacial ice. But it was the fourth and final glaciation period, the Wisconsin Ice Stage, that left the most lasting impact on Minnesota’s landscape. From around 100,000 BCE to about 7,000 BCE the Wisconsin Ice Stage moved glacial ice back and forth across the landscape, once again reshaping the land and depositing sediment.

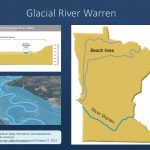

As the climate warmed and the ice retreated, Glacial Lake Agassiz formed from meltwater around 10,000 BCE. Dwarfing all of today’s Great Lakes combined, Lake Agassiz covered most of the Canadian province of Manitoba and spilled over into parts of Saskatchewan, Ontario, and the American states of North Dakota and Minnesota. The enormous lake covered over 123,500 square miles and reached depths of 400 feet. At various times, the lake drained through a variety of routes, and its water found its way to the oceans. During two separate periods, around 9,500 to 9,000 BCE and again around 7,900 to 7,400 BCE, Glacial River Warren drained Agassiz water and carved a path through southern Minnesota 300 feet deep and up to five miles wide. Today, we can see the remnants of Agassiz in the Red River, which runs through its dried-up bed, and we can see what remains of the River Warren’s path in the Minnesota River Valley. The results of these climatic variations, moving and then melting ice, and raging waters have created the landscape we know today.

Glaciation

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

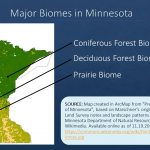

Minnesota is unique in that it sits on the meeting points of ecological systems, weather patterns, and watersheds. Three continental biomes meet in Minnesota. The mixed coniferous forest biome covers the northeast portion of the state, while the prairie biome defines the southwest and western boundary. In the seam between these two lay the deciduous forest biome of hardwoods that runs northwesterly through the middle of the state. Each of these biomes is characterized by different weather patterns and corresponding vegetation growth.

The state is at the meeting point of two continental divides, which create three major watersheds. In the northwest and northern portions of the state, 34% of the state’s water drains through the Red River drainage basin and out through Hudson Bay. The northeast part of the state, an area known as the arrowhead region, sends about 9% of the state’s water through Lake Superior, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, and eventually to the Atlantic Ocean. Most of the state’s water, 57%, is collected by the Mississippi drainage basin and sent south to the Gulf of Mexico.

Biomes and Watersheds

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

Overlaying these watersheds is a network of rivers that tie the landscape together. The continent’s most celebrated river, the Mississippi, begins at Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota and runs south to the Gulf of Mexico. The Falls of St Anthony in Minneapolis sit on the Mississippi at the ecological seam between biomes and near other major rivers. The location and waterpower of the falls are, in large part, responsible for the development of Minneapolis. Dredged by the Army Corps of Engineers to allow for barge traffic up to the falls, the Mississippi River continues to serve as a vital north-south artery throughout our recent history. But its location, when viewed from its proximity to other waterways, had made it critically important centuries before barges appeared on its waters. Travelers going west along the Great Lakes could travel out of Lake Superior through the St Louis River, portage a relatively short distance to the St Croix River (which defines the border between eastern Minnesota and northwest Wisconsin), and follow that to where it drains into the Mississippi about 20 miles south of Saint Paul. This geography puts Minnesota at the junction point of an east-west, north-south water route through the heart of the North American Continent.

Because of its prominence, European nations and later the United States used the Mississippi River repeatedly as a political boundary. When the American colonies won their independence from Great Britain in 1783, treaty negotiators used the river to define the western boundary of the newly created United States. While negotiators had a relatively clear understanding of the river’s north-south course through the middle of the continent, their understanding of its upper regions was less certain. Using a map that misrepresented and obscured the origin of the Mississippi, negotiators assumed it lay west of Lake of the Woods and declared that the new boundary ran “to the said Lake of the Woods; Thence through the said Lake to the most Northwestern Point thereof, and from thence on a due West Course to the river Mississippi.”[1] In 1832, the United States and Great Britain determined that the Mississippi began at Lake Itasca, south, not west, of the Lake of the Woods. This realization left a little piece of Minnesota surrounded by the waters of Lake of the Woods on three sides and Canadian territory on the fourth. This geographical oddity is known as the Northwest Angle, is the northern-most point in the lower 48 states and gives credibility to the state motto: “L’Etoile du Nord (Star of the North).” In 2021, just over 100 Minnesotans lived on the Angle – they need to take a boat, travel over lake ice, or go through Canada to get to the mainland United States.

Other rivers have also played an important role in our history. The Red River that defines the boundary of Minnesota and North Dakota runs nearly straight north through what once was Glacial Lake Agassiz. As a result of its ecological history, the Red River Valley is home to some of the continent’s most fertile soil. The Minnesota River was called the St. Pierre River by the French and then the Saint Peter’s River by the British before the Americans settled on its Dakota name – Minnesota. Largely used for recreation today, it makes the rough V shape through the southern part of the state. It follows the same path long ago carved by the Glacial River Warren, but only at a tiny fraction of the ancient river’s width and volume.

Major Rivers in Minnesota

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

Regardless of its impressive network of rivers, Minnesota is better known for its over 15,000 lakes, mostly sprinkled through the northern part of the state. Nowhere are these lakes more celebrated than in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCA), which is located in northeastern Minnesota and connected to Canada’s Quetico Provincial Park north of the international boundary. The BWCA is part of the Superior National Forest and spans over a million acres, encompasses 1,100 lakes, and is visited by over 150,000 tourists in a typical year. The current designation of the BWCA came out of the 1978 BWCA Wilderness Act that aimed to balance Minnesotans’ desire to preserve the environmental jewel with the hopes of those living close to it that they might make a living by logging and attracting tourists. This tension is a theme that will run through Minnesota’s history and show up at various times and in a variety of places.

Minnesota’s northeastern boundary, running along the shoreline of Lake Superior from Duluth to the Grand Portage, makes up what Minnesotans call their North Shore. The state’s connection to Lake Superior and therefore to the other Great Lakes, the St Lawrence Seaway, and the Atlantic Ocean, has always been important for travel and trade. From the International ports at Duluth and Two Harbors, to the commercial fishing enterprises that once sprinkled the shoreline north to Canada, to today’s tourist-based businesses, the lake has provided Minnesotans living in the Arrowhead Region with a unique culture and lifestyle for generations.

Like the Boundary Waters, Lake Superior has also been a tension point between those hoping to make a living off the water and the shore, and those striving to ensure its preservation. One example of this tension occurred in the early 20th century when the Welland Canal opened between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, allowing large sea-going ships to travel into Lake Superior to the western ports at Duluth and Superior, Wisconsin. The canal was certainly important economically for the state and the region, but the ships unintentionally introduced sea lamprey into the lake, an invasive species that devastated the lake trout populations.

Minnesota is also home to three iron ranges spread throughout its northeastern region. The Cuyuna, Vermillion, and Mesabi Ranges began producing ore in the late nineteenth century and provided much-needed iron that, when processed into steel, helped build the nation and win two world wars. The ore also attracted large numbers of immigrants, primarily from Scandinavia and Eastern Europe, who provided the back-breaking and dangerous work required to harvest the ore from underground and open pit mines. Multi-ethnic range towns with unique cultures developed throughout the region as a result. Here, too, we can see an example of economic and environmental tensions. In the 1950s, Minnesotans discovered a way to process low-grade ore from the Mesabi Range into taconite pellets that could be easily transported across Lake Superior for processing into iron and steel. While the taconite industry employed thousands of Minnesotans and supplied the nation with much-needed steel and iron, the processing required to reduce the ore-containing rocks into pellets created a significant amount of waste material. Initially, from the 1950s to 1980, this waste material was flushed into Lake Superior, harming the water quality and threatening the lake.

In both being stewards of the environment and capitalizing on the opportunities it provides, Minnesota has set aside parts of its landscape for environmental protection and to attract tourists. The state is home to 52 state parks, 11 state forests, and nine wildlife management areas. Minnesota also contains six national parks: Voyageurs National Park, Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, Pipestone National Monument, North Country National Scenic Trail, and the Grand Portage National Monument. The number and variety of Minnesota’s parks play into the out-of-doors culture that many identify with the state.

The landscape in Minnesota, carved by glaciers and at the crossroads of watersheds and biomes, drew people here and defined what they did upon arrival. It also, however, continues to provide economic opportunities and preservation challenges.

People

Section Highlights

- How people first came to be in North America and Minnesota is not clearly known, but scholars have emphasized that migration across Beringia played a role.

- Minnesota’s landscape holds evidence of a fascinating prehistoric past that spans the Paleo, Archaic, Woodlands, and Mississippian archeological periods

- People living during the Woodlands and Mississippian periods constructed thousands of burial mounds in Minnesota – examples of these can be seen at Saint Paul’s Indian Mounds Park and Grand Mound in northern Minnesota.

- From 5,000 BCE to the 1760s, Minnesotans carved petroglyphs in rock outcropping near Jeffers, MN – leaving intriguing clues about the state’s ancient past.

Traditionally, scholars have explained the peopling of North America by emphasizing migrations that occurred over Beringia – the land bridge that long ago connected what is today Siberia in Russia to current-day Alaska. Climatic changes exposed Beringia for thousands of years between 28,000 BCE and 8,000 BCE. Anthropologists, archaeologists, historians, and linguists have tracked three waves of migrants who moved into the Americas across Beringia and have hypothesized that some arrived along coastal water routes as well. While these migrations did indeed bring people to North America and Minnesota beginning around 12,000 BCE, it is doubtful that those people were the first to arrive. In 2009, archaeologists discovered fossilized human footprints in New Mexico’s White Sands National Park and studied them for decades. In 2021, scientists determined that the oldest of the footprints date from about 21,000 BCE, meaning people were here during the ice age – nearly 10,000 years earlier than previously thought. Clouding this story even further, Dakota people, who can track their history in Minnesota the longest, believe they have always been here, emerging from Mother Earth at the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers.

Regardless of the uncertainty about how people came to be–or always were–in North America, it is certain that people living in what would one day become Minnesota were part of an ancient and storied past. Beginning with small groups of big-game hunters, to the development of trade networks, gender roles, and spiritual beliefs, to the slow spread of farming and the emergence of larger, more sedentary communities, ancient Minnesotans were part of a fascinating past that reaches back before our collective memory. Evidence of this prehistoric past is still visible today – buried in the ground, etched into stone, and built into earthen mounds.

Some of the earliest evidence of human occupation in Minnesota came in the form of human remains discovered by accident in the early 1930s. In the summer of 1931, a road crew near Pelican Rapids discovered the remains of a teenage girl who had likely drowned around 8,000 BCE. Originally and inaccurately dubbed Minnesota Man, she has since been known as Minnesota Woman, Pelican Lakes Woman, or Lady of the Lake. At the time of her death, she carried with her an elk-antler dagger and a conch-shell necklace or sash. Given that the shells had come from Florida, her discovery suggested that there was an extensive trade network operating during her lifetime. Three years later, in 1933, an amateur archaeologist discovered the remains of an adult male in a gravel pit near Browns Valley on what long ago was an island in Glacial River Warren. Scientific analysis of his remains suggests Browns Valley Man lived around 6,000 BCE, maybe 2000 years after the Lady of the Lake. At the time, these discoveries were among the best preserved remains yet discovered and furthered our understanding of how long ago people occupied North America. While their lifetimes were perhaps separated by thousands of years (precise dating of the remains continues to be elusive), both lived in western Minnesota, near the outlet of glacial Lake Agassiz, and give us a glimpse of the scope of our prehistoric past. While studied, displayed, and kept in private hands during the middle of the 20th century, the remains of both have since been returned to their indigenous descendants and buried in North Dakota.

Browns Valley Man and Lady of the Lake Markers

- Browns Valley Man Historical Marker

- Minnesota Woman Historical Marker

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

The Lady of the Lake most likely lived at the very end of what archeologists call the Paleoindian Period, which was characterized by big game hunters who lived in small extended family groups. They were the first people to leave an archeological record in North America, and their culture endured until climate change caused the extinction of the animals they hunted. If our understanding of his age is accurate, Browns Valley Man lived at the beginning of the Archaic period, which ran from around 8,000 to 500 BCE. During that span of thousands of years, Minnesota’s climate became warmer and drier. People adapted to their immediate surroundings, tools and projectile points became more refined, communities grew a bit larger, and gender roles and spiritual beliefs developed further. Archaeologists believe the lives of Archaic people in Minnesota varied greatly by their immediate environment and that they perhaps used snowshoes, toboggans, canoes, and lived in bark or skin-covered lodges. Excavations of archaic sites in Minnesota have yielded bison remains, copper tools, projectile points, and remnants of hunting camps.

Around 500 BCE, a gradual but notable change occurred that ushered in the Woodland Period (named so because it was first identified occurring in the eastern wooded areas of what would become the United States). This period lasted until about 1,000 CE and is characterized by important innovations such as the extensive use of pottery, the emergence of the bow and arrow, and a more focused dependence on agriculture that, among other things, allowed for larger community development. While the woodland culture diminished in most of Minnesota around 1,000 CE, in the far north it remained isolated and intact until French explorers reached the area in the middle of the 1600s. Also notable is that woodland cultures in Minnesota began gathering, managing, and eating wild rice – an activity that has since become so important to the Dakota and Ojibwa, and continues to define a significant part of Minnesota’s culture.

Our most lasting connections to woodland-era life in Minnesota are the burial mounds people left. There were 12,000 or more in Minnesota alone, although less than ½ of that number survived the 19th-century Euro-American farmers. In the metropolitan area of Minneapolis/St Paul, the only remaining examples are protected within the boundary of Indian Mounds Regional Park on Dayton Bluff overlooking St Paul. Although the city has not always done an adequate job of respecting the sanctity of the site, beginning in 2021, visitors are reminded that “this is a cemetery” as they enter the park. Six of the original 58 mounds are protected by the park’s fencing. Scholars believe the mounds had been constructed between 200 BCE and 400 CE. Nineteenth-century excavations produced carved animals, utensils, pottery, ceremonial pipes, copper tools, and human remains.

The state’s largest burial mound is located along the Canadian border at the confluence of the Rainy and Big Fork Rivers near International Falls. The site is currently owned by the Minnesota Historical Society but has been closed to the public since 2005. It contains five burial mounds, ancient villages, and fishing sites. The largest mound is about 15 times bigger than the average burial mound, and might, some scholars suggest, be an effigy of a serpent or a muskrat.

In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), the same act that sent the remains of the Lady of the Lake and the Browns Valley Man to the Dakota for proper burial, put a legislative halt to burial-mound excavations in the nation. In Minnesota, a state law enacted in the 1970s had already put an end to that controversial practice.

Burial Mounds in Minnesota

- Indian Mounds Regional Park

- Indian Mounds Regional Park

- Indian Mounds Regional Park

- Indian Mounds Regional Park

- Indian Mounds Regional Park

- Grand Mound

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

As European encroachment loomed, a Mississippian culture emerged in middle America around 700 CE and flourished until contact. Centered along the Mississippi and its tributaries, this last prehistoric culture was characterized by full-time farming and aided by an extensive trade network. The culture was dominated by the huge city of Cahokia, which was in what is today Southern Illinois, across the Mississippi River from St. Louis. Emerging around 900 CE, Cahokia reached its peak around 1100 CE when the city spanned six square miles and perhaps housed as many as 20,000. It was the largest pre-Columbian city north of Mexico. For reasons unknown today, the city began to decline around 1350, but not before connecting the vast middle continent, including people living in Minnesota, in a cultural network that boasted complex religious, political, and economic institutions. Today, Cahokia Mounds State Park is designated as a World Heritage site.

Among the most fascinating remnants of Minnesota’s prehistory are the 5,000 petroglyphs carved into the Sioux quartzite outcroppings in southwestern Minnesota between the small towns of Jeffers and Comfrey. Created by Native American ancestors, the images permanently etched into the stone record people, ceremonies, religious beliefs, animals, atlatls (spear-throwing sticks), thunderbirds, shamans (religious leaders), and turtles. Because the earliest petroglyphs are believed to have been created around 5,000 BCE and the most recent during the 1760s, the site is one of the oldest continually utilized sacred sites in the world. It is also the largest collection of petroglyphs in the Midwest and is currently a historic site operated by the Minnesota Historical Society, where it, along with the local Dakota community, preserves and interprets the site for the public. Noting the spiritual significance of the Jeffers Petroglyphs to the Ioway, Otoe, Cheyenne, and Dakota people, the historical society notes:

Jeffers Petroglyphs is a special place. To Native Americans who reside in and around the state, it is a very spiritual place — one where Grandmother Earth speaks of the past, present, and future. To descendants of those who left these markings, this is a place of worship, a prayer place, likened to other places of worship such as a church, synagogue, or mosque.[2]

Jeffers Petroglyphs

Jeffers Petroglyphs

Photographs by Aaron Bommarito, July 31, 2020.

NOTE: You can click on these images to enlarge them. After viewing an image, use your browser’s back arrow to return to the book.

Conclusion

Minnesota was created by glaciation that left a varied landscape sprinkled with lakes and a network of rivers. While located in the north from a national perspective, it is near the center of the North American Continent and sits on the seam of ecological biomes and continental watersheds. It is also located at the western end of the Great Lakes and houses the starting point of the Mississippi River, putting it at a junction point of an east-west, north-south waterway. These unique features become incredibly important for Minnesota’s history.

Minnesota’s environment, resources, and location brought prehistoric people here and dictated what they did once they arrived. While we only have a brief and frustratingly incomplete glimpse of what life may have been like all that time ago, what we do know connects Minnesota to the larger picture of pre-Columbian America.

Suggestions for Further Inquiry

Gibbon, Guy. Archaeology of Minnesota: The Prehistory of the Upper Mississippi River Region. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Johnson, Elden. The Prehistoric Peoples of Minnesota. Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.

“Prehistoric Period: An Overview of Prehistoric Archaeology in Minnesota (12,000 BC – AD 1650),” Sate Archeologist, Minnesota Department of Administration. https://mn.gov/admin/archaeologist/educators/mn-archaeology/prehistoric-period/ (accessed March 29, 2022).

- "Treaty of Paris, National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/treaty-of-paris (accessed March 29, 2022). ↵

- "The Rock," Jeffers Petroglyphs, Minnesota Historical Society. https://www.mnhs.org/jefferspetroglyphs/learn/rock (accessed March 29, 2022). ↵

The Wisconsin Ice Stage is the most recent period in which glaciers covered parts of what today is the northern United States (including Minnesota). This last glaciation period lasted from about 73,000 BCE to about 9,000 BCE and left the most last impact on Minnesota's geography.

Minnesota's Northwest Angle in Lake of the Woods is farther north than any other part of the contiguous United States. Logically, it would seem that this area of about 123 square miles should be in Canada. But this oddest feature of the entire U.S.–Canada boundary was the proper result of American treaties negotiated with Great Britain.

William Lass, MNOpedia,

The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is located in the northern third of Superior National Forest. It is the most heavily used wilderness in the country, with about 250,000 visitors annually.

Julia Lavenger, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/boundary-waters-canoe-area-wilderness-bwcaw

The Arrowhead Region is located in the northeastern part of the U.S. state of Minnesota, so called because of its pointed shape.

The Cuyuna Iron Range is a former North American iron-mining district about ninety miles west of Duluth in central Minnesota. Iron mining in the district, the furthest south and west of Minnesota’s iron ranges, began in 1907. During World War I and World War II, the district mined manganese-rich iron ores to harden the steel used in wartime production. After mining peaked in 1953, the district began to focus on non-iron-mining activities in order to remain economically viable.

Fred Sutherland, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/cuyuna-iron-range

The Mesabi Iron Range wasn’t the first iron range to be mined in Minnesota, but it has arguably been the most prolific. Since the 1890s, the Mesabi has produced iron ore that boosted the national economy, contributed to the Allied victory in World War II, and cultivated a multiethnic regional culture in northeast Minnesota.

Alex Tieberg, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/mesabi-iron-range

Voyageurs National Park is located on the Minnesota–Ontario international border and is Minnesota’s only national park. Established in 1975, it is a 341-square-mile network of lakes and streams surrounding the Kabetogama Peninsula. Though the region has been home to various Indigenous nations for countless generations, the park is named for the predominantly French Canadian voyageurs (travelers) who transported furs and other trade goods between hubs like Montreal and points further west.

Karl Nycklemoe, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/voyageurs-national-park

The Grand Portage National Monument in far northeastern Minnesota was established in 1960, after the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (Ojibwe) ceded nearly 710 acres of their land to the US government. A unit of the National Park Service (NPS), it consists of the eight-and-a-half-mile Grand Portage trail and two trading depot sites—one on the shoreline of Lake Superior and one inland, at Pigeon River. A partially reconstructed depot sits at the Lake Superior site.

Christopher Homerding, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/grand-portage-national-monument

The six burial mounds at St. Paul’s Indian Mounds Park are among the oldest human-made structures in Minnesota. Along with mounds in Crow Wing, Itasca, and Beltrami Counties, they are some of the northernmost burial mounds on the Mississippi River. They represent the only ancient Native American burial mounds still extant inside a major US city.

Paul Nelson, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/indian-mounds-park-st-paul

Jeffers Petroglyphs is an internationally significant Native American sacred site and the location of the largest group of Indigenous petroglyphs (rock carvings) in the Midwestern United States. Situated in Dakota homeland, it is sacred to multiple Native American nations, including the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Iowa, and Ojibwe.

Thomas Sanders, MNOpedia - https://www.mnopedia.org/place/jeffers-petroglyphs