7 Health Care Policy

Katherine Knutson; Karin Lund; and Matthew Vierzba

Wondering why some text is in blue? Click here for more information.

7.0 Health Care Policy

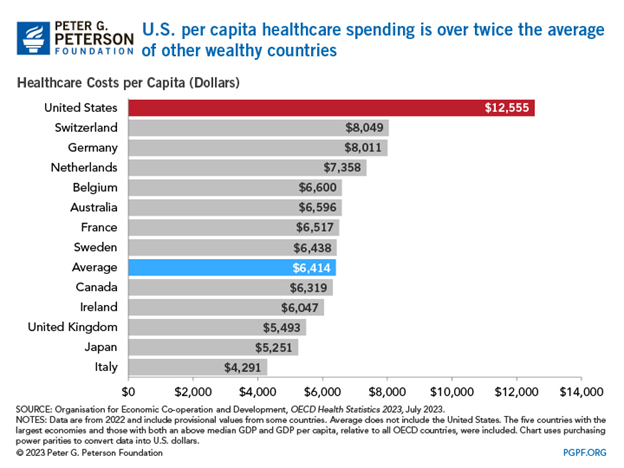

The U.S. boasts some of the best medical care in the world, including the renowned Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. But that quality comes at a high price. The U.S. spends more than $13,000 per person, per year on health care.[1] This is more than twice the amount that people in the United Kingdom, Australia, France, Japan, or Canada spend on health care each year.[2] Furthermore, the U.S. ranks first among the nations for the highest percentage of its gross domestic product (GDP) going towards health care costs, with 17% of the U.S. GDP spent on health care.[3] The federal government alone spends nearly $2 trillion on health programs and services each year.[4]

Figure 7.1: Healthcare spending in the U.S. compared to other countries. Peter G. Peterson Foundation. Retrieved [March 27, 2024], from https://www.pgpf.org/blog/2023/07/how-does-the-us-healthcare-system-compare-to-other-countries

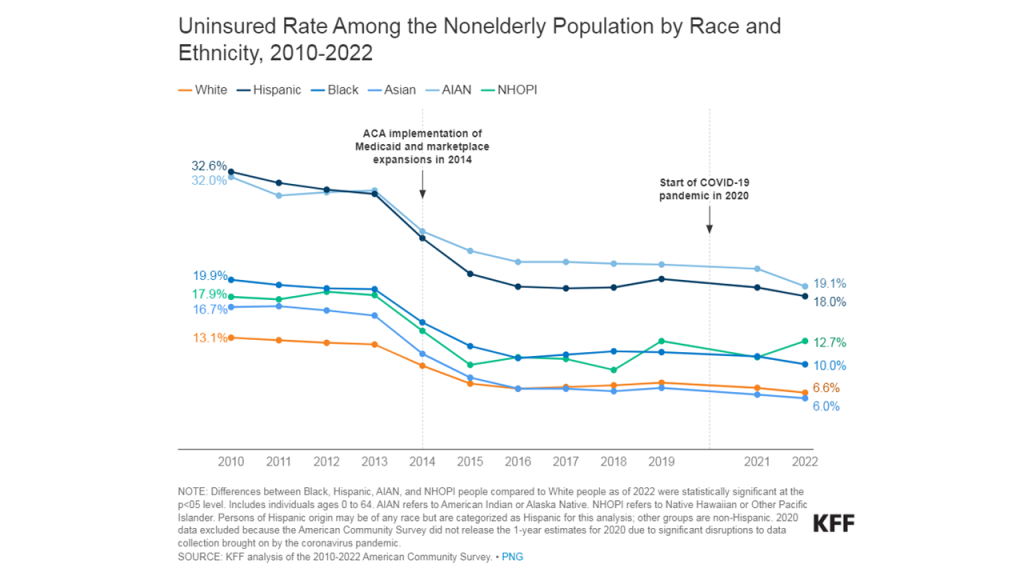

Ironically, however, the U.S. has a lower life expectancy than many other developed countries.[5] The average American will live 77.5 years while in comparable countries, life expectancy is over 82 years.[6] The U.S. also has shockingly high rates of infant mortality, chronic disease, and obesity.[7] 26 million Americans lack health insurance.[8] Access to health care is not evenly distributed, with nonelderly American Indian and Alaska Natives and Hispanic Americans twice as likely to be uninsured compared to Whites.[9]

The gap between what we spend on medical care and what we get in terms of health outcomes is at the heart of debates over health care policy in the U.S. Health care policy includes laws, regulations, and government actions (or inaction) that influence access, delivery, quality, and funding of medical care, including both physical and mental health. Health care policy is closely related to public health policy. According to the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, public health policy is the “laws, regulations, actions, and decisions implemented within society in order to promote wellness and ensure that specific health goals are met.”[10]

Providing access to quality and affordable medical care is a classic example of a collective action problem. A collective action problem is a situation in which everyone would be better off if they worked together to achieve a goal, but their conflicting interests and personal self interest keep them from doing so.[11] One type of collective action problem is called the free rider problem.[12] A free rider problem develops when people who benefit from a resource (health, for example) either don’t pay or under pay for the resource. One of the most controversial issues in debates over health care is whether people should be required to carry health insurance, a solution to the free rider problem. The requirement that hospitals treat all patients is another example of where the free rider problem comes up in health care policy.

7.1 Major health care policies

The government has long been involved in protecting the health and wellbeing of citizens, starting when the federal government established a military hospital in 1798, which was the precursor to the current Public Health Service. Another milestone was passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act (amended in 1938 as the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act), which established the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to ensure access to safe food, medication, and medical devices.

Modern health care policy in the U.S. is shaped by three major policies: Medicare, Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act. Medicare and Medicaid were both created in 1965 and the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010.

Figure 7.2: The three main health care policies in the U.S.

Medicare

Medicare is a federal program providing medical insurance to people ages 65 and older and younger people with certain disabilities. It is considered an entitlement program, meaning that if you meet the qualifications for the program, the government is required to provide the program benefits to you. It is funded through payroll taxes and administered by the federal government through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, a unit within the Department of Health and Human Services.

The Medicare program has four distinct parts. Part A covers health care costs associated with hospitalization. People are automatically enrolled in Medicare Part A when they reach age 65. Medicare recipients pay a deductible and then Medicare pays the rest of the cost of hospitalization up to 60 days per illness.[13] Part A also pays for recovery time in a nursing home following a hospitalization and for hospice care for terminally ill people. The funding for Medicare Plan A comes entirely from payroll taxes. Workers earning less than $200,000 per year are taxed 1.45% and their employers match that amount. Workers earning more than $200,000 are taxed 2.35%, matched by their employers.[14]

Medicare Part B is optional and covers physician care like trips to the doctor’s office and laboratory and diagnostic tests. It has a small monthly premium and yearly deductibles. Though Medicare Part B recipients do pay some of the costs associated with health care through their premium and deductible, the federal government ends up paying about three-fourths of the total cost of the care. Part B makes up the biggest share of government spending in the Medicare program.[15]

Medicare Part C, also called Medicare Advantage, allows Medicare recipients to enroll in private health plans to cover the services provided in Parts A and B. Part C is entirely voluntary. Part C was created through the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 as a mechanism for reducing Medicare spending by shifting people to private plans.[16]

Finally, Part D provides recipients with a discount drug card to make prescription drugs more affordable. Part D was created through the Medicare Prescription, Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, more commonly known as the Medicare Modernization Act. Part D is also a voluntary program. Part D recipients pay a monthly premium and a deductible in exchange for coverage of prescription medications. The Inflation Reduction Act made it possible for Medicare to negotiate some drug prices directly with drug companies to lower the cost of prescription medication for consumers.

As of 2020, there were more than 63 million enrollees in Medicare, which is about 19% of the U.S. population, and the government spent more than $769 billion per year on the program. Medicare falls in the category of mandatory spending, meaning that the government is required to provide the funding to cover those who are eligible for the program rather than allocating a specific amount of money in each year’s budget. As a result of the rising costs of medical care and the growing number of people eligible for Medicare, spending on Medicare has increased dramatically. In 1970, Medicare made up 3% of federal spending. By 2020, it was 12% of federal spending. And by 2051, it is estimated to make up 20% of federal spending if the policy remains the same.[17]

Medicaid

Like Medicare, Medicaid was established in 1965. Medicaid serves low income adults and children and the disabled. Additionally nearly one-third of nursing home care is covered by Medicaid. A related program, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, created in 1997, provides insurance and preventative care for uninsured children. About one-third of all children are covered through either Medicaid or CHIP.

Medicaid and CHIP are funded collaboratively by the states and the federal government but administered entirely by the states under federal guidelines. As of 2023, there were about 90 million enrollees in the program, representing about 21% of the population.[18] In eight states, Medicaid and CHIP cover more than 25% of state residents.[19]

Like Medicare, Medicaid is an entitlement program and spending on Medicaid is part of the mandatory portion of the federal budget. In 2020, the government spent about $458 billion on Medicare with approximately two-thirds of that cost covered by the federal government.

While Medicaid and CHIP are predominantly funded by the federal government, they are administered by state government agencies. States have some flexibility to create a version of the Medicaid program that works best in their state, though they do have to meet some federal requirements regarding eligibility and services provided. State Medicaid programs are required by the federal government to cover hospital care, nursing home care, physician care, laboratory services, immunizations, and family planning services.[20] States can choose to provide coverage for things like prescription drugs, dental care, or vision care. Many state Medicaid programs have their own name. For example, Medicaid in Minnesota is called Medical Assistance. Medical Assistance covers about 18% of Minnesota residents.

Affordable Care Act

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, commonly known as “Obamacare” was enacted in 2010. At the time the bill was being debated, about 48 million people lacked health insurance (about 18% of the population under age 65) but by 2020, following passage of the ACA, that number had fallen to 30 million (11% of the population under age 65).[21] In 2022, the number of uninsured Americans hit a record low of 26 million.[22]

As passed, the bill was over 1,200 pages long and changed nearly every aspect of the healthcare system. Rather than establishing an entirely new program, the Affordable Care Act expanded eligibility for existing programs, incentivized state action, and restricted some of the behavior of insurance companies. The ACA increased access to health insurance by expanding eligibility for Medicaid. The federal government encouraged states to expand Medicaid coverage to adults with incomes up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (currently $20,120 for an individual) and then provided additional funding to cover the majority of the cost. As of 2022, 40 states and the District of Columbia have chosen to expand Medicaid.[23]

To keep insurance costs low, the ACA mandated that all people purchase health insurance (through their employer, the government, or the private market) or pay a penalty. The so-called individual mandate provision survived a 2012 legal challenge at the Supreme Court but was repealed in the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017.[24] The theory behind the individual mandate was that, without it, the only people who would willingly purchase health insurance would be those who needed a lot of medical care, overtaxing the system.

In addition to the provisions to expand access, the government encouraged states to create health insurance exchanges, or marketplaces. The exchange is a website in which individuals can view, compare, and purchase individual insurance plans. The federal government also created an exchange for people living in states that did not create their own. Additionally, the federal government provides subsidies to people who are not eligible for Medicare or Medicaid but can not afford individual plans. Consumers need to purchase their insurance through an exchange in order to receive income-based subsidies. Practically speaking, most people get their insurance through their employer or through Medicare or Medicaid. However, the exchanges help people who are self-employed or employed by a small business that isn’t required to offer health insurance. There is an open enrollment period each year from November 1 to January 15 in which people can enroll in a new insurance plan.

Finally, the ACA included several protections for patients such as prohibiting insurance companies from denying coverage based on preexisting conditions, requiring insurers to allow families to keep their children on their insurance plans until age 27, requiring insurance plans to cover services such as preventative screenings, maternity care, mental health, and hospital care, and eliminating annual or lifetime caps on benefits. Prior to the ACA insurance companies could, and did deny coverage to people who had preexisting conditions such as a past history of cancer or diabetes, making it nearly impossible for some people to purchase medical insurance.

One provision in early drafts of the Affordable Care Act was something called the “public option.” The public option refers to a government-run health insurance plan open to anyone. This provision was removed from the proposal before the final vote, but the idea has continued to surface in Democratic circles, most recently in calls from some presidential candidates to create a “Medicare for all” program.

Major trends and themes

Three major themes stand out in debates over health care policy. The first is the dependence on the private market to provide both health care services and insurance. The second is the impact of partisanship on policy making. The third is the growing understanding of the interconnectedness between physical and mental health and other factors impacting wellbeing. Let’s take a moment to briefly explore these three themes.

The Private Market

One of the defining features of the U.S. healthcare system is its reliance on the private market to provide services and funding. Unlike in many other industrialized countries (the U.K. and Canada, for example), the health care system in the U.S. developed within the private market rather than being run by the government as a single-payer system. In a single-payer health care system, the government pays the bills for health expenses of all citizens rather than processing medical payments through insurance companies. As a side note, the U.S. does have two systems that function as single-payer health systems: the Veterans Health Administration and the Indian Health Service. In both of these systems, the government not only funds the health care, but also provides most of the health care services directly.

Health insurance began to develop in the 1930s during the Great Depression to help pay the cost of medical treatment. The number of people purchasing private health insurance grew in the 1940s, but the industry expanded significantly in the 1950s and beyond. One of the major factors that precipitated the growth of health insurance was a 1954 federal law that exempted insurance offered by employers to their employees from federal and payroll taxes.[25] The change in the tax code created an incentive for businesses to provide health insurance to their employees; businesses had to pay taxes on wages but not on health insurance benefits. It also created an incentive for employees to favor employer-provided insurance because the benefit was also tax-free for employees. Today, this benefit (the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance) adds up to a massive amount, reducing federal and state tax revenue by $273 billion in 2019.[26]

At the end of World War II, President Harry Truman proposed a national insurance plan to provide coverage to all Americans.[27] Doctors, represented by the American Medical Association, and hospitals, represented by the American Hospital Association, vigorously opposed such a system because they believed it would lower profits to doctors and hospitals.

Once Medicare and Medicaid were established in 1965 and most other people received insurance through their employer, the demand for a government-run single-payer system declined. It wasn’t until the late 1980s and early 1990s that growing costs pushed the issue back into public consciousness. By 1991, 90% of Americans “felt that American health care needed to be fundamentally changed or completely rebuilt.”[28]

Partisanship

A second important trend, at least since the 1960s, has been the impact of partisanship on health care policy making. Passage of Medicare and Medicaid was possible because Democrats controlled both chambers of Congress by a 2-to-1 majority and Democrat Lyndon Johnson won the presidential election by a landslide. Establishing a health insurance program for the elderly and the poor was a priority for Democrats and they had the institutional power to do it.

Later efforts to reform the healthcare system in the early 1990s by President Bill Clinton failed, in large part due to opposition from Republicans and advocacy groups representing the insurance industry.[29]

In the vote for the Affordable Care Act, not a single Republican in the House or the Senate voted in favor of the bill. Over the next decade, Republicans tried unsuccessfully to repeal the ACA. In 2016, Republicans won control of both chambers of Congress and the White House and “repeal and replace” was a major campaign theme. Yet, despite Republican majorities, a bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act failed in the Senate when three Republican senators (John McCain, Susan Collins, and Lisa Murkowski) joined with all of the Democrats in voting against the bill.

Republicans have successfully framed efforts toward providing universal health care as “socialized medicine.”[30] This phrase emerged during Truman’s efforts to pass universal care and it has continued to be a common refrain.[31] As communications professor Jeff St. Onge argues in his review of the term, “…Republicans could not convince every citizen that every Democrat was a socialist, but without a doubt the organized opposition to health care reform was successful in positioning the issue as a choice between liberty and socialism, and thus as strengthening a perception that government intervention in health care issues should be viewed with extreme distrust.”[32]

In more recent years, some Democrats have embraced the “socialist” label, with people like Senator Bernie Sanders and Representative Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez identifying as Democratic Socialists and advocating for “Medicare for All.”

Social Determinants of Health

Healthcare providers and political actors are increasingly aware of the ways in which physical and mental health are inextricably linked to a variety of other factors. Public health scholars and practitioners refer to social determinants of health (SDH) as “conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”[33] Essentially, these are non-medical factors that impact health outcomes.

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion within the Department of Health and Human Services identifies five categories of social determinants of health:

- Economic stability – Economic factors like poverty, unemployment, food insecurity, and housing insecurity affect health outcomes and, relatedly, health conditions affect the ability of people to work and achieve economic stability.

- Education access and quality – People who have obtained higher levels of education are healthier and have longer lives. Access to early childhood education, completing high school, and access to and enrollment in higher education affect health outcomes. For example, infant mortality rates in the U.S. are higher among mothers who didn’t finish high school.[34]

- Health care access and quality – People without health insurance or a primary care provider are less likely to seek medical care, leading to negative health outcomes.

- Neighborhood and built environment – Geographical factors such as the quality of housing, exposure to crime and violence in home communities, and environmental conditions such as the quality of air or water or access to parks and bike paths all impact health outcomes. For example, children who are exposed to lead in substandard housing have lower cognitive functioning.[35]

- Social and community context – Having a community of support through healthy relationships with family, friends, coworkers, and neighbors is related to health outcomes.

Figure 7.3: Healthy People 2030, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Retrieved [March 1, 2024], from https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

These social determinants of health contribute to health disparities, or avoidable differences in health outcomes that exist between different groups of people. Recent research suggests that SDH might account for up to 50% of health outcomes, which means that policymakers interested in improving health outcomes need to look beyond simple changes to health care policies.[36]

7.2 Who are the players?

Federal official actors

There are multiple congressional committees that have strong involvement in health care policy. In the Senate, the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee and the Subcommittee on Health Care (within the Finance Committee), and in the House, the Health Subcommittee (within the Energy and Commerce Committee) and the Ways and Means Committee have primary jurisdiction over health issues. There are, however, over 40 other committees and subcommittees that touch on health-related topics.[37]

During debate over the Affordable Care Act, for example, three separate House committees (Energy and Commerce; Ways and Means; and Education and the Workforce) held nearly 80 hearings on the proposal. Similarly in the Senate, the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee and the Finance Committee held dozens of hearings and roundtable discussions.

In the executive branch, the President obviously plays a major role in shaping the agenda for health care policy. For better or worse, presidents are closely associated with proposals or policies passed under their administration. In 2013, Gallup conducted an interesting experiment, asking members of the public about the Affordable Care Act but using different ways of describing it. When people were asked about the “Affordable Care Act,” with no mention of President Obama, 45% approved of it. When they were asked about “Obamacare,” with no mention of the ACA, only 38% approved of it.[38] People’s perception of the law was shaped not by the provisions of the policy itself, but rather by its affiliation with the president. In case you’re wondering, public support for the ACA currently stands at just under 60%.[39]

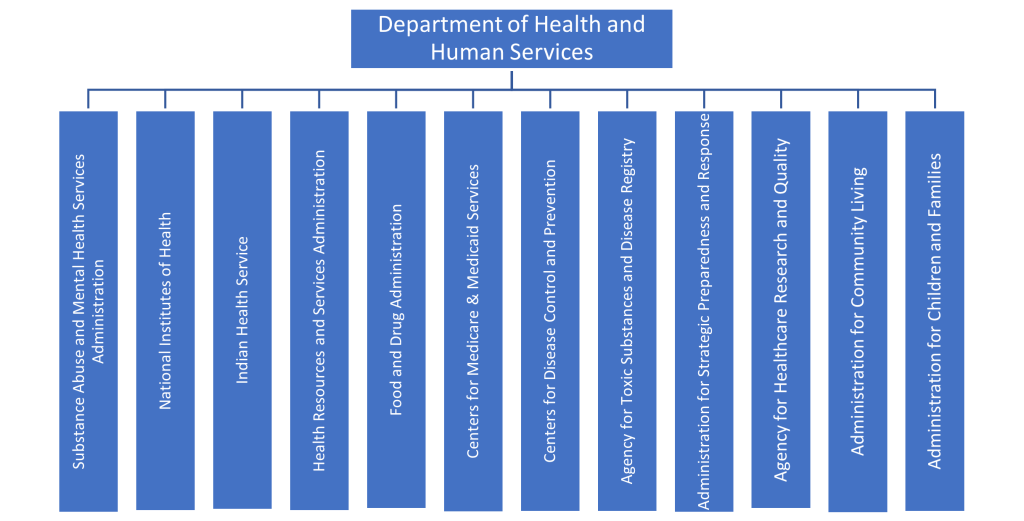

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is the federal agency with primary responsibility over health care in the U.S. The Secretary of Health and Human Services is nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Formed in 1953, HHS has twelve main operating divisions, many of which focus on a distinct aspect of health care. I’ll highlight a few of the divisions that are especially influential in shaping and enforcing health care policy.

Figure 7.4: Divisions within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is responsible for promoting health and preventing disease, injury, and premature death. Based in Atlanta, Georgia, one of the agency’s first tasks was combating the spread of malaria in the U.S.[40] Today, the CDC also responds to global outbreaks such as Ebola in West Africa and the COVID-19 pandemic. The CDC conducts research and disseminates health information to the public. Over 20,000 people spread across over 60 countries work for the CDC.[41] Currently, the director of the CDC is a political appointee who does not require Senate confirmation, but beginning in 2025, the agency’s director will need Senate confirmation.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) oversee Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP. CMS also certifies nursing homes and oversees the health insurance marketplaces. CMS employs about 6,000 people, most of whom work at their headquarters near Baltimore, Maryland

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates prescription and over-the counter medication, vaccines, medical devices, cosmetics, tobacco products, electronic products that give off radiation, and most food (The U.S. Department of Agriculture has primary responsibility for regulating meat, poultry, and egg products). About 20% of products purchased in the U.S. are regulated by the FDA.[42] The FDA employs more than 18,000 people at offices and laboratories across the country. New medical drugs or medical devices go through an extensive review process to ensure their safety before being approved for sale in the U.S. by the FDA.

The Indian Health Service (IHS) provides comprehensive health care services to any American Indian or Alaska Native who is a member of one of 574 federally recognized tribes in 37 states. The IHS provides health care to over 2.56 million people and directly operates 24 hospitals and over 75 health centers staffed by about 6,500 public health professionals.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) conducts and funds biomedical research. About 10% of its research budget funds research at NIH facilities, with about 80% of its budget funds research projects at colleges, universities, and other research institutions.[43] The NIH operates research institutes such as the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Finally, it’s important to mention the Public Health Service, The modern version of the Public Health Service was established in 1870 and in 1995, it came under the auspices of HHS. It currently falls under the Assistant Secretary for Health, and is overseen by the Surgeon General. The PHS operates within nearly all of the HHS divisions including within the NIH, FDA, CDC, and IHS. About 6,000 employees within the PHS are uniformed and commissioned officers, like other members of the military, and this service is considered active military service. The PHS has the mandate to protect and promote the health and safety of the public.

Outside of the agencies associated within the Department of Health and Human Services, another key health-related agency is the Veterans Health Administration (VA), housed within the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The VA provides care to 9 million veterans each year at over 1,300 health care facilities around the country staffed by over 113,000 health professionals.

As with other policies, the courts have played a major role in shaping health care policy. Following passage of the Affordable Care Act, multiple lawsuits challenged various provisions. In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the individual mandate but also held that the federal government couldn’t require states to expand Medicaid coverage.[44] In a 2021 case, California v. Texas, the Court rejected another effort to challenge the ACA.[45] The 2014 case Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores is another example of the Court’s role in policymaking.[46] The Affordable Care Act required that employers offer health insurance that included contraception coverage for employees. Hobby Lobby argued that this provision violated the religious beliefs of the company’s owners and that, as a privately-held business, the company should be exempt from the policy. The Supreme Court agreed, allowing a for-profit corporation to avoid the requirement because of their religious beliefs.

State and local official actors

State and local governments have traditionally held broad authority over public health and safety stemming from the Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which reads that “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the People.” The doctrine of state police power “has traditionally implied a capacity to…promote the public health, morals, or safety, and the general well being of the community…”[47] As a result, state and local governments play a large role in setting and enforcing health-related policies.

Most state legislatures have standing committees focused on health. To give you a glimpse of the level of policy making activity in the states, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, in 2023 alone, there were 1,771 bills related to public health and 825 bills related to prescription drug access and affordability that were introduced in the 50 states and the District of Columbia.[48] In Minnesota, the House Health Finance and Policy Committee and the Senate Health and Human Services Committee take the leading role in drafting policy related to health care.

State executive leaders can spearhead efforts to shape health care policy and those state efforts can even spread to other states or to the federal level. Portions of the Affordable Care Act were modeled after a 2006 health care policy from Massachusetts passed under Republican governor Mitt Romney. The Romney policy included an expansion of Medicaid, an employer mandate to provide insurance, subsidies for low income individuals, and an online insurance exchange, all of which made their way into the Affordable Care Act.[49]

Every state has a health department. Some state departments are explicitly focused on public health, while others pair health with either social services or the environment. These departments are led by either a secretary of health or state health commissioner, a position usually appointed by the Governor. The Commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Health oversees an office of about 1,500 employees and a $500 million budget.[50] MDH staff monitor infectious disease outbreaks and air and water quality. They have a special focus on advancing health inequities caused by structural racism.[51]

While state health departments play an important role, local health departments are on the front lines of implementing health care policy. Across the country, about 3,000 local health departments provide community health services, track health conditions, and engage in disease prevention efforts.[52]

In Minnesota, about 70 local health departments are guided by the Local Public Health Act and have a set of priorities that include: promoting healthy behavior and healthy communities, preventing the spread of communicable diseases, responding to emergencies, and identifying gaps or barriers in health-related services.[53] When you think about health-related services provided by the government, a lot of these activities are carried out by local health departments. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, local health departments offered free testing and, later, vaccines. Local health departments inspect restaurants, grocery stores, and schools to ensure safe food and sanitary conditions. Public health nurses from local health departments provide support to new parents through home visitation programs.[54] Most of the funding for local public health departments in Minnesota comes from local taxes and fees. About 34% comes from the federal government and the remaining 15% or so comes from the state.[55]

Finally, the state courts can play a role in shaping health care policy.[56] State courts are especially likely to hear cases about individual medical situations involving patients and doctors or insurance companies. For example, a patient whose insurance denies covering a certain procedure might sue or a family might seek a court order to remove a family member from life support (or to force the medical providers to keep them on life support). On their own, each case decision does not necessarily set policy, but taken together, they definitely influence both the delivery of health care and health care policy.[57]

Unofficial actors

Advocacy groups play a major role in shaping health care policy and they spend a lot of money to do so. In fact, four out of the top six organizations that spent the most money lobbying in 2023 were connected to the healthcare industry.[58] There are five major categories of advocacy groups active in this debate. First, health care providers are represented by trade and professional associations. Among the largest and most powerful of these is the American Medical Association (AMA), a professional association representing over 270,000 physicians and medical students. Similar professional associations exist for other medical professionals such as the American Nurses Association and the American Counseling Association. Institutions are also represented by trade associations such as the American Hospital Association and the American Health Care Association and the National Center for Assisted Living. The American Hospital Association was the third biggest spender on lobbying in 2023, spending over $30 million to shape policy.

A second category of groups includes those representing health insurance companies and related industries. Of these, America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), a group representing the health insurance industry, was instrumental in helping defeat the Clinton health reform proposal. Individual health insurance companies also pursue their own lobbying efforts independent of organized groups.

The third category of groups includes those representing the medical industry. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) has historically been one of the loudest and most persuasive voices in resisting efforts to allow the government to negotiate drug prices for Medicare recipients. The Medical Device Manufacturers of America is another trade group that spends heavily to influence policy. In 2022, the group spent $1.2 million on advocacy efforts. Again, individual companies that produce medical products are likely to be involved in advocacy efforts.

Groups representing employers make up the fourth category. These groups are involved in the debate because most Americans get their health insurance through their employer. The National Federation of Independent Businesses and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce have been particularly active participants in health care policy debates.

Finally, there are many active groups representing patients. Broad citizen groups like Families USA or AARP (formerly known as the American Association of Retired Persons) and specialized groups like the American Cancer Society or the Autism Society monitor policies that are relevant to their constituent groups, lobby, and encourage their members to participate in advocacy efforts.

Policy itself is shaped in part through the work of think tanks and research organizations. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and KFF (formerly known as the Kaiser Family Foundation) provide policy makers and the public with high quality, nonpartisan information related to health care.

Most major universities operate health policy or public health research institutions, which not only produce and disseminate information that is useful to policymakers but also train future policymakers. Students at these institutions might earn a Master of Public Health, preparing them to engage in healthcare policy making or public health education efforts.

And, as always, citizen activists can play a big role in shaping health care policy. Laws are sometimes named after a particular individual whose situation inspired the legislation. For example, the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act was passed in 2022 to support access to mental health care for medical professionals in honor of Dr. Lorna Breen who died by suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic.[59] In Minnesota, the Alec Smith Insulin Affordability Act passed in 2020 was championed by the mother of a 26-year old who died as a result of being unable to afford the high cost of insulin.[60] These types of individual cases that point to larger trends offer compelling feedback to policymakers.

7.3 Why are we talking about this now?

Health care is nearly always on the institutional agenda in some way, shape, or form. Throughout the years, the federal government has made incremental changes to health care policy, such as creating a prescription drug policy for Medicare or funding programs to provide breast and cervical cancer screenings to members of racial and ethnic minority groups.[61] The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was, however, a seismic shift in health care policy in the U.S. One scholar of health care policy called it “the most significant reform of our health care system since the 1965 enactment of Medicare and Medicaid…”[62] The Punctuated Equilibrium theory helps explain the timing of the law’s passage.

Punctuated Equilibrium theory argues that most of the time, policymaking is characterized by long periods of stability. During these moments of equilibrium, policy change is incremental and is controlled by a relatively small group of policy actors operating within a policy subsystem. In the case of health care reform, congressional leaders and interest group leaders, particularly the influential American Medical Association, America’s Health Insurance Plans, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, and Chamber of Commerce, engaged in heavy lobbying to maintain the status quo and resist major changes to the health care system.

However, public concern over the state of health care access began to grow in the mid 2000s and the campaign leading up to the 2008 presidential election opened the door to change and helped to destabilize the policy monopoly. Public opinion surveys from 2008 indicated that health care was one of the top concerns of voters. At the time of the election, 44 million Americans were uninsured and millions more were underinsured.[63] The first forum of the campaign season featuring the Democratic candidates was held in March of 2007 and focused largely on health care.[64]

As the primary field narrowed, leading Democratic candidates Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama outlined proposals for reforming health care. Clinton supported an individual mandate, requiring all people to have health insurance, while Obama’s plan required only children to have insurance but mandated employer coverage. Ultimately, Obama won the primary election and went on to face Republican Senator John McCain in the general election. In contrast to Obama, McCain proposed moving away from employer-sponsored insurance and instead giving tax credits to individuals who purchase health insurance.[65]

After winning the general election, Obama faced a challenging economic situation (the country was in the midst of “the Great Recession”) but Obama continued to prioritize health care reform despite some advisors who encouraged him to focus on other issues. Two months into his term, Obama convened a White House summit on health care reform, bringing together congressional leaders from both parties and key interest group leaders.[66] Throughout the next few months, Obama continued to focus public attention on health care reform through his public speeches and interactions with Congress. In a speech to a joint session of Congress on September 9, 2009, Obama introduced his proposal for comprehensive health reform, presenting it as a middle path between liberal and conservative approaches.

In explaining the breakdown of a policy monopoly, Punctuated Equilibrium Theory calls our attention to pressures from both external and internal sources. Contextually, the debate over Obama’s health care proposal was happening in the midst of a massive shock to the economic system. The housing market collapsed and many banks failed between mid-2007 and mid-2009. The unemployment rate spiked, reaching 10% by October 2009 and thousands of people lost their homes and savings.

While not a traditional focusing event because it unfolded over several months, the Great Recession served to focus attention on the need for government intervention to stabilize the economy. Indicators such as the foreclosure rate, unemployment rate, and GDP helped communicate the problematic nature of the economy during this period of time. Obama drew an explicit connection between the country’s economic woes and health care during the first few months of the debate over health care reform.[67] An analysis of his public rhetoric reveals that during this initial period, Obama emphasized the economic benefits of health care reform and the economic harms that would result from the failure to act. Comprehensive health care reform “was portrayed in Obama’s speeches as one solution to help resolve the economic crisis.”[68] By linking this economic framing of health care reform to the focusing event of the Great Recession, Obama helped to create external pressure on the policy monopoly.

Additionally, internal pressures were building. The election of Obama over McCain was coupled with Democratic majorities in both chambers of Congress, giving Democrats unified control over both branches of government for the first time since 1993. The campaign helped focus attention on health care reform because it was a priority for most of the candidates. The Obama administration also worked proactively with interest groups that had opposed health care reform in the past to shift their preferences. In the end, the Obama administration was able to secure support from the American Medical Association, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the American Hospital Association, and America’s Health Insurance Plans.

The death of longtime senator and advocate of health care reform, Ted Kennedy (D-MA) and the surprising election of Republican Scott Brown in January 2010 to replace him, spurred Democrats in Congress to act quickly. Brown’s election gave Republicans in the Senate 41 seats, which allowed them to filibuster Senate proposals. To work around this impediment, Democrats passed legislation in the House which would then be considered by the Senate under a special procedure called reconciliation, which is not subject to the filibuster.[69]

From this point, there was still a lot of political maneuvering that happened leading up to the final vote on the bill in March of 2010, but the combination of pressures from both internal and external sources helped weaken the policy monopoly that had dominated health care policy making since the late 1960s.[70]

7.4 How is policy made?

Access to reproductive health care, particularly abortion, has been one of the most contentious political issues over the past fifty years. Although Congress has waded into the issue, policymaking in the area of reproductive health has been driven by the courts and the states. In this section, I’ll walk through two recent examples of policy making related to access to reproductive health care that shifted across venues from state legislative to federal judicial action.

The controversial Texas Heartbeat Act (Senate Bill 8), enacted in September 2021, bans abortions in Texas once cardiac activity can be detected in the embryo, which happens at around 6 weeks into a pregnancy, often before a woman even realizes she is pregnant. The law provides no exceptions for pregnancies resulting from incest or rape. It permits abortions for a narrow segment of health reasons if the pregnancy could endanger the mother’s life or lead to “substantial and irreversible impairment of a major bodily function.”

The Texas Heartbeat Act was introduced by Texas Republican Senator Bryan Hughes on March 11, 2021. Republican Representative Shelby Slawson introduced a companion bill (HB 1515) into the Texas House of Representatives a day later. The bill was strongly supported by Texas Governor Greg Abbott and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, and was a priority for Republicans, who controlled both chambers of the legislature.

The Senate State Affairs committee, chaired by Senator Hughes, held a public hearing on March 15, which featured testimony from 65 witnesses. Later that day, the State Affairs committee voted 7 to 2 to send the bill to the full Senate for consideration. The full Senate voted to approve the bill on March 30 by a vote of 19-12. All Republican Senators and one Democratic Senator voted in favor of the proposal; all of the votes opposed to the proposal came from Democrats.

Following a successful vote in the Senate, the House sent the bill to the Public Health Committee for consideration. The committee held a hearing on April 7 featuring testimony from over 25 witnesses. Just over a week later, the committee approved the proposal by a vote of 6 to 4. The full House voted to pass the proposal on May 6 by a vote of 83 to 64. There were slight discrepancies between the two versions and so the Senate voted on May 13 to approve the amendments from the House. The finalized bill was immediately sent to Governor Abbott, who signed the bill on May 14, 2021. The controversial new law went into effect on September 1, 2021.

At the time of its passage, the Texas Heartbeat Act seemingly violated the guiding legal precedent Roe v. Wade (1973) as well as other subsequent Supreme Court decisions protecting a woman’s right to obtain an abortion during the first two trimesters of pregnancy.

In Roe the Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision, established that the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment protects a woman’s right to privacy, which includes the right to terminate a pregnancy in the first two trimesters (approximately six months of pregnancy) when the fetus is incapable of surviving outside the womb (a concept referred to as viability).[71] When Roe was decided, about two thirds of the states had policies banning or significantly restricting access to abortion that had to be rewritten in order to conform to the new precedent.[72] In response, legislators in many states immediately began introducing proposals to create other restrictions on access to abortion, introducing 188 anti-abortion bills across 41 states within three months of the decision.[73]

Nearly two decades later, the Court reiterated the constitutional right to abortion in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992) but also ruled that states can enact pre-viability abortion restrictions as long as those restrictions don’t create an undue burden on a woman’s access to abortion.[74] That decision allowed states to implement mandatory waiting periods, parental consent laws, and other types of restrictions. The Court had a chance to strike down both precedents in 2016 when challenges emerged from a state ban on abortion after six weeks passed by North Dakota and a state ban on abortion after twelve weeks passed by Arkansas. The Court declined to hear those cases, which meant that the lower court decisions striking down those laws as unconstitutional violations of Roe were upheld.

The Texas law sidestepped the precedent set by Roe by explicitly barring state officials from enforcing it. Instead, the Heartbeat Act deputized private citizens (Texans or not) by allowing them to sue anyone who performs an abortion or “aids and abets” a procedure. While patients could not be sued, doctors or someone who provided transportation to a patient could be sued for up to $10,000 plus legal fees.

The design of the policy also made it particularly difficult to challenge in court because it is hard to know who to sue to block it. Nevertheless, abortion providers and abortion rights activists in the state immediately sued to block the law as an unconstitutional violation of Roe. Their case, Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson, was eventually appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the Court declined to block the law from going into effect. The federal government also attempted to block the bill in a related lawsuit, U.S. v. Texas, but again, the Court declined to block implementation of the law.

Instead, the Supreme Court agreed to hear both cases during three hours of oral arguments in November, 2021. Rather than focusing on the substantive constitutional question of whether the law violated the precedent set by Roe, the Court focused only on the procedural question of whether the entities challenging the law had the legal standing to do so. The legal principle of standing is that a person needs to be able to demonstrate that a policy directly harmed them in order to bring a lawsuit. Ironically, the design of the policy itself seemed antithetical to the legal principle of standing, since it allowed anyone to bring a suit against an abortion provider.

In December 2021, the Court ruled that abortion providers in Texas could challenge the law by suing some state officials in federal court, specifically state licensing officials, like the executive director of the Texas Medical Board, who are authorized to take disciplinary action against abortion providers who violate the law. But the Court refused to block the law as a whole and instead sent it back to the state trial court for consideration.

Instead of going back to the state trial court, at the request of the state of Texas, the federal appeals court (5th circuit), sent the case directly to the Texas Supreme Court to rule on whether the state licensing officials that were mentioned in the U.S. Supreme Court decision have the power to enforce abortion law. This was viewed by opponents of the law as a delay tactic and an attempt by state leaders to avoid a lower court decision that would have sided with abortion providers.

In March 2022, the Texas Supreme Court ruled that state officials did not have power to enforce the law “directly or indirectly” and so could not be sued. “The act’s emphatic, unambiguous and repeated provisions” declare that a private civil action is the “exclusive” method for enforcing the law, the justices wrote. They added, “These provisions deprive the state-agency executives of any authority they might otherwise have to enforce the requirements through a disciplinary action.”

Texas’ law sparked efforts in several conservative states to pass similar policies. Idaho enacted a similar law in 2022, allowing family members of the “preborn child” to sue abortion providers for up to $20,000. The Idaho ban included an exception for abortion in the case of rape or incest but only if the woman had filed a police report for the crime.

While this case was capturing national media attention, another case–which proved to be even more significant in the history of reproductive health policy–was winding its way through the legal system. In March 2018, the state of Mississippi passed the Gestational Age Act banning abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy. The law contained exceptions for medical emergencies but not for rape or incest. The Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the only abortion clinic in the state of Mississippi, immediately sued to block enforcement of the law arguing that it was in direct violation of the Supreme Court precedent set in Roe (1973) and Casey (1992).

A federal district court judge sided with the Jackson Women’s Health Organization, blocking enforcement of the Gestational Age Act the day after the bill was signed. The judge eventually ruled the ban unconstitutional in November 2018. The state of Mississippi appealed this ruling to the Fifth Circuit Court, where a three-judge panel issued a ruling upholding the district court judge in December 2019.

Again, Mississippi appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. In December 2021, the Supreme Court held oral arguments on the case Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. “Dobbs” refers to Thomas E. Dobbs, State Health Officer of the Mississippi Department of Health.

The legal question in the Dobbs case was “whether all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are unconstitutional.” In a landmark ruling, by a 6-3 vote, the Supreme Court overturned forty years of precedent, finding “the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion; Roe and Casey are overruled; and the authority to regulate abortion is returned to the people and their elected representatives.”[75]

Immediately following the decision, states scrambled to respond. Several states had so-called “trigger laws”, or bans on abortion access that were designed to take effect immediately if Roe was overturned. Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, and South Dakota are examples of states where existing laws prohibiting abortion became enforceable following Dobbs. Within the first two months following the Dobbs decision, over 100 bills restricting abortion were introduced. 14 states currently have total or near-total bans on abortion and 21 states have restrictions that limit abortion earlier in the pregnancy than what Roe allowed.[76] An additional three states have abortion bans that have currently been blocked by a judge.

Other states moved to protect access to abortion. Since Dobbs, 18 states have passed laws protecting the right to abortion or access to abortion. Currently, abortion is legal in 26 states and the District of Columbia.

7.5 Why does policy look like this?

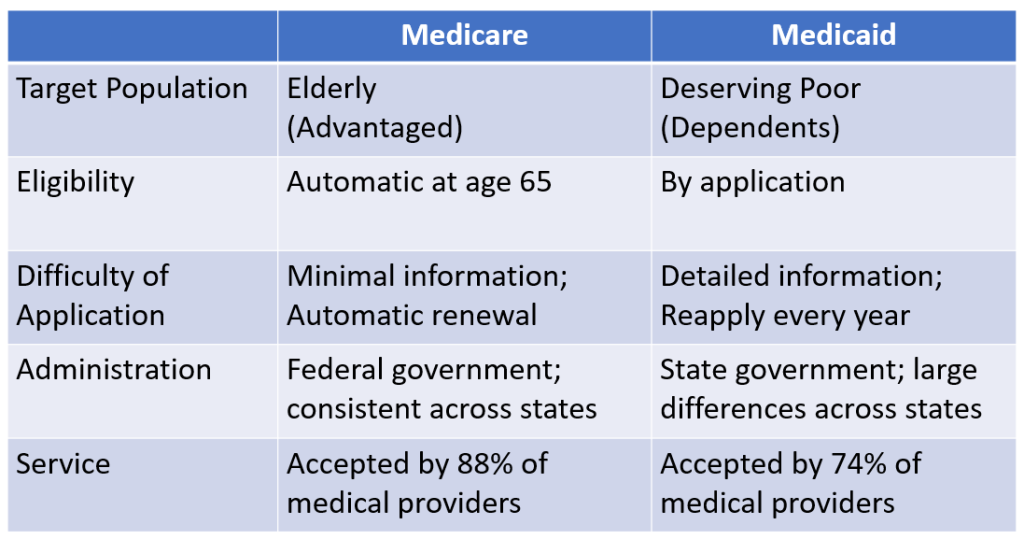

Social Construction Theory points us to consider the political power and social construction of target populations to understand the selection of policy tools. Let’s use the theory to explore the differences in policy tools used in the two major health care policies in the U.S.: Medicare and Medicaid. Both programs were enacted in 1965 as amendments to the Social Security Act.[77] Just under 40% of the U.S. population is covered by either Medicare or Medicaid, with the numbers split nearly evenly between the two programs. However, the target population and policy design of each program are very different.

The target population for Medicare are Americans ages 65 or older who qualify for Social Security. As they are today, older Americans in the 1960s tended to be more actively involved in politics than younger Americans.[78] Additionally, at the time of Medicare’s passage, the population of those ages 65 and older was growing, promising increased political power from the elderly. The AARP (originally known as the American Association of Retired Persons) was founded in 1958 to represent Americans over the age of 55 in politics.

Today, of course, the elderly continue to be among the most powerful demographic groups in U.S. society. In the 2020 presidential election, 76% of people over the age of 65 voted compared to only 51% of those ages 18-24.[79] In the 2022 elections 34% of the people who voted were 65 or older.[80] Older Americans are also much more likely to donate money to political campaigns. Open Secrets found that the average age of the top 500 donors to federal campaigns in 2014 was 65.6.[81] Research finds that older Americans are also more likely to contact elected officials, attend local government meetings, and work or volunteer for campaigns compared to those ages 18-29.[82] Elderly Americans were also politically strong in the 1960s. Today, the AARP is one of the largest and most powerful interest groups active in U.S. politics.[83]

In terms of social construction, the elderly tend to be viewed favorably by the public. In 1965, the elderly were part of a cohort known as the “lost generation”, a group that included veterans of World War I and those who lived through the Great Depression and World War II. While there is scholarly debate about whether negative stereotypes about the elderly were, and are, prevalent, in general, the elderly maintain a positive social construction.[84]

Using the Social Construction Theory, Americans ages 65 and older would fall into the Advantaged category because of their strong political power and positive social construction. We would expect to see policies targeted toward Advantaged populations providing benefits with very few associated burdens.

In looking at the policy as it was designed, all Americans ages 65 or older are automatically eligible for Medicare and are automatically enrolled in Medicare Part A.

Those receiving Social Security retirement benefits between age 62 and 65 are automatically enrolled in Medicare Part A and Part B when they turn 65. Those applying for Social Security benefits at 65 sign up for Medicare at the same time. Those who defer Social Security benefits because they are still working, sign up for Medicare online. The process of applying for Medicare involves creating an online account and providing a few basic pieces of information:

- Social security number

- Location of birth (city, state, country)

- Start and end dates for any current health insurance plans

- Valid email address

Medicare coverage automatically renews every year, so recipients don’t need to re-enroll every year once they complete the initial enrollment process.

Though Medicare tends to reimburse medical providers at lower rates compared to private insurance, almost all medical providers accept Medicare.[85] Most Medicare recipients contribute to Medicare through payroll or income taxes during their working years, however, “…most current beneficiaries receive substantially more in benefits–in the range of 5 to 10 times more–than they contributed to the system….”[86]

To summarize, Medicare, a policy targeted toward an Advantaged target population, is a policy that provides oversubscribed benefits (more than deserved) to recipients with very minimal barriers to accessing those benefits.

In contrast to Medicare, the target population for Medicaid at the time of its creation was limited to specific subgroups of poor people. Before the ACA, there were three groups of people who were eligible to receive Medicaid:

- Poor families with children (as defined by the federal poverty level).

- The elderly poor (Low-income people aged 65 or older who qualify for the Supplemental Security Income program (SSI)).[87]

- The disabled poor (People under aged 65 with long-term disabilities who qualify for SSI).

States could decide to cover additional low-income subgroups under Medicaid such as pregnant women in families above the poverty level.[88] As a result, before the ACA, the target population varied considerably between states, though all recipients were economically poor.

Poor people in the United States have historically held very low levels of political power. In 1964, just under 54% of the poorest 20% of the population voted compared to 85% of the richest 20%.[89] Poor people are also less likely to donate money to political campaigns, contact elected officials, engage in political campaigns, or be affiliated with political organizations.[90] While there are advocacy organizations that represent poor people, they are not as powerful, as visible, or as large as interest groups representing those with money.[91]

Research in political science and sociology devotes a lot of attention to discussion of society’s construction of the distinction between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor. As sociologist Herbert Gans argues in his book, The War Against The Poor, the “deserving” poor includes “the sick and old, as well as the working poor,” all of which are “considered good or worthy of help.”[92] Gans traces the development of the social construction of the “undeserving” poor, a group that includes “able-bodied nonworking poor people.”[93] He points out that there has often been a racial dimension to the labeling and stigmatizing of the “undeserving” poor, with poor people of color more likely to be cast as “undeserving”.

Using the Social Construction Theory, the target population for Medicaid when it was first enacted were people who fell within the category of the “deserving” poor. This group had a positive social construction but low levels of political power, placing them within the Dependent category. Social Construction theory predicts policy designs that confer benefits but require recipients meet eligibility requirements that “often involve labeling and stigmatizing recipients,” in this case based on their income level and lack of material resources.[94]

In looking at the policy as it was designed, Medicaid eligibility is based on financial status related to taxable income. To get Medicaid coverage, a person first has to see if they or their family members are eligible. Since each state has its own requirements, a person (or family) might qualify in one state but not in another. Eligibility depends on a combination of factors including age, income, the number of people in the family, and whether a person is pregnant or has a disability (traditional indicators of “deservedness”).

Medicaid was originally designed as a voluntary program for the states, so states could decide whether or not they wanted to participate. It wasn’t until 1982 that all 50 states participated in the program. As a state-run program, eligibility and benefits vary considerably between the states. “Poor people who are eligible for care in one state will often be ineligible in another. Treatments covered in one state may not be covered in another.”[95] Additionally, beginning in 1977, the Hyde Amendment prohibited the states from spending any federal funds to provide abortion services through Medicaid except in cases of rape, incest, or if the mother’s life is in danger.

To access Medicaid benefits, an eligible person (or family) must create an online account and then fill out a state Medicaid application. In Minnesota, the application requires providing the following information:

- A social security number for each person applying.

- The date of birth for everyone in the household (not just the people applying for coverage).

- A driver’s license, Tribal identification, or other identification

- A Green Card or other immigration documents for non-citizens

- Last year’s 1040 tax form for each person applying.

- The two most recent pay stubs for each person applying.

- Documents for other sources of income for each person applying (social security, unemployment, self employment, etc.).

- A W2 form or Employer Tax ID Number for each person applying.

- Information about any employer-sponsored health insurance available to each person applying, even if they aren’t enrolled in it.

Recipients must reapply for benefits each year, often providing the same type of detailed information required in their initial application.

Physician reimbursement rates are lower in Medicaid than Medicare and lower compared to employee-sponsored insurance plans. As a result, fewer physicians accept Medicaid insurance. One study found that only 74% of providers accept Medicaid patients compared to 88% of providers who accept Medicare and 96% who accept private insurance.[96] This can make it difficult for people with Medicaid to access health care services.[97]

In other words, compared to Medicare, Medicaid is a policy targeted toward a Dependent target population. While the policy does provide benefits, recipients face multiple barriers in receiving those benefits. In addition to navigating a complex system that is different from state to state, the application process is rigorous, must be repeated every year, and calls attention to the socioeconomic status of the recipient. And, in the end, it is still difficult for recipients to access service because so many medical providers don’t accept Medicaid patients.

Figure 7.5: Comparing Medicare and Medicaid

As Kant Patel and Mark Rushefsky summarize, “the generally accepted political explanation for the creation of Medicaid is that the program was created almost as an afterthought to Medicare.”[98] This sends an important political message to program recipients about their place and value in society. Patel and Rushefsky add that“…the Medicare program has enjoyed public popularity and legitimacy because it is tied to Social Security, a program that is contributory in nature (i.e., through Social Security taxes paid by workers). In contrast, from the beginning, Medicaid was burdened by the stigma of being associated with public assistance (i.e. welfare) programs…”[99] Again, the Social Construction Theory helps to explain the design of these policies and the effects of these designs on the target populations.

The Affordable Care Act made significant changes to the Medicaid program by…”making benefits available to all people who are poor, regardless of health status or family status.”[100] In practice, the ACA expanded to people earning up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. However, Medicaid continues to be a voluntary program and As of February 2024, 10 states have not yet expanded Medicaid, refusing to cover childless adults who are not disabled, pregnant, or elderly.[101]

Several politically conservative states have sought federal permission to adopt work requirements for Medicaid recipients and the Trump administration encouraged states to request a waiver that would allow them to implement such requirements. Kentucky was the first state to adopt work requirements in 2018. Under their proposal, Medicaid recipients between the age of 19 and 64 would need to complete 80 hours per month of community engagement (work, school, job skill training, or community service) or risk losing benefits. Kentucky’s plan was blocked by legal action. During the Trump administration, 13 states applied and were granted a waiver to implement work requirements but the Biden administration withdrew approval. Currently no states currently have a policy in place.

7.6 Does it work?

Most cost-benefit evaluations of Medicare and Medicaid have found them to be generally efficient programs compared to private insurance.[102] As Donald Barr notes, evaluators often look at how much of the cost of an insurance program goes into administration versus how much is spent on patient care. “Employer-based insurance typically spends 10 to 30 percent of costs on administration and other expenses not related to patient care (e.g. corporate profit). For nonprofit HMOs such as Kaiser Permanente, this figure is in the range of 5 to 8 percent. Medicare Part A spends 1 to 2 percent of all funds on administrative costs; the figure for Part B is typically 2 to 2.5 percent. Using this measure of administrative efficiency, traditional Medicare is one of the most efficient medical payment systems in the country.”[103] In contrast, “administrative costs for Medicare Advantage, operated by market companies, average about 14 percent of revenues.”[104] Similarly, research finds that “Medicaid costs 27 percent less for children and 20 percent less for adults than private insurance.”[105]

One major goal of the Affordable Care Act was to reduce health disparities between people from different racial and ethnic groups.[106] Multiple studies have explored the extent to which the ACA has reduced racial and ethnic disparities in terms of access to health insurance. These outcome evaluations have generally found some improvement in racial and ethnic disparities concerning access to insurance, but they have also found that disparities persist.

Using data from the American Community Survey, researchers compared the number of uninsured people from different racial and ethnic groups over time.[107] In 2008, before the ACA was adopted the uninsured rate among the non-elderly was 26% among those identifying as Black and 42% among those identifying as Hispanic. In comparison, only 15% of those identifying as White were uninsured. In 2014, after implementation of the ACA, the percentage of uninsured people had dropped significantly, but the largest changes were among those identifying as Black or Hispanic. 21% of those identifying as Black and 33% of those identifying as Hispanic were uninsured in 2014. The coverage gap between Whites and people of color fell more dramatically in states that expanded Medicaid eligibility compared to states that did not.[108]

Another study looked at the impact of the ACA on access to insurance for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders and found that the ACA completely reduced the gap between this group and Whites in terms of health insurance coverage.[109]

Despite these gains, research finds that there continue to be disparities in access to insurance based on race and ethnicity.[110] Recent data indicates that, while only 6% of White Americans lack health insurance, over 19% of American Indian and Alaska Natives and 18% of Hispanic people lack health insurance.

Figure 7.6: Trends in access to health insurance by race. KFF. Retrieved [March 28, 2024], from https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity/

Other research has looked at questions related to the extent to which patients can access care and the extent to which they use preventative health care services. Here, results are mixed. For example, using data from the National Health Interview Survey, researchers looked at whether people visited an emergency room or visited a physician.[111] They found that, controlling for other factors, the ACA increased the probability of having a physician visit by 3%, though there was not a statistically significant improvement for African Americans. Similarly, the same researchers looked at whether people delayed necessary medical care. They found that, controlling for other factors, Latinos were less likely to have delayed care after implementation of the ACA, though there was no statistically significant difference for African Americans.[112]

These types of mixed findings have led one researcher to conclude that, “even when policies are intended to winnow racial disparities [like the ACA], politics can undermine the steps necessary to do so.”[113]

Policy evaluation efforts surrounding the ACA also provide us with a good example of process evaluation. One of the key features of the ACA was the development of health insurance exchanges, websites designed to make shopping for a health insurance plan on the open market easier and more transparent. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services were responsible for hiring contractors to build a website for the federally facilitated marketplace, something that eventually became HealthCare.gov. Construction of the website began in September 2011 and was supposed to be fully functional by the start of the open enrollment period on October 1, 2013. However, by one account, only six people were able to sign up for insurance on the first day and it was weeks before the website began to work properly.[114] Additionally, construction of the website ended up significantly over budget, ultimately costing over $2.1 billion.

In addition to government-sponsored evaluation efforts, such as an investigation by the U.S. Government Accountability Office and the Office of Inspector General in the Department of Health and Human Services, private companies and universities have used it as a case study to help avoid similar mistakes in the future.[115]

7.7 What is an executive presentation? (by Karin Lund)

One of the most common ways to share information in the business world is through verbal presentations with accompanying slides. This method of communication is especially common when you have to persuade or update executives – leaders typically at the VP or c-suite level. A 15-minute presentation can make or break whether you receive funding for a project, gain the right solution to a problem, or effectively manage change. Becoming an excellent executive presenter takes time and practice, but here are the four main steps to the process.

Develop your presentation strategy.

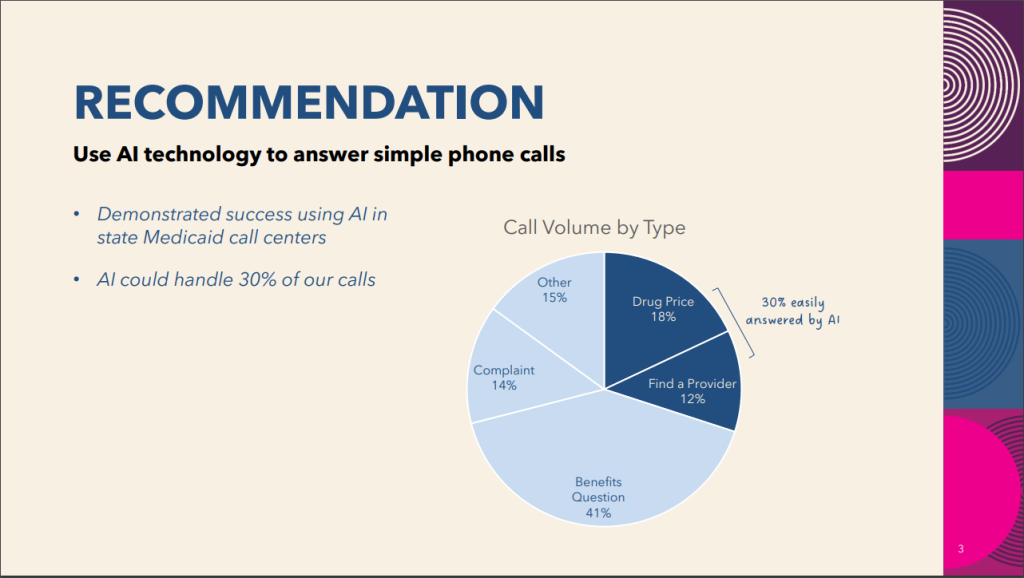

The first step is considering your desired outcome, who you are presenting to, how you will present. Let’s say you work for a company that has a government contract to run a call center for Medicare patients and you are asking c-suite leaders at your company for $1 million to pilot using AI to answer calls that come into your contact center. You want the leaders to agree with your proposal and give you the money – that’s your desired outcome. Next, you consider your audience. You’ll be presenting to a subset of the c-suite, which includes the Chief Executive Officer, the Chief Operating Officer, and the Chief Financial Officer. Take time to conduct a stakeholder analysis and put yourself in their shoes. What do each of these individuals value? What concerns might they have? Keep the answers to these questions in mind as you build your presentation.

You also have to consider the logistics of your presentation. Is it virtual or in-person? Will you have a way to share slides on a projector or large screen? How long do you have? Typically, you’ll have about 30 minutes for an executive presentation, but that includes time for questions, so you’ll want to plan about 15 minutes of presentation time.

Create your story.

This is where you do a lot of brainstorming, as you are working on developing your main points and supporting details and how those flow together. One way to do this is to write each idea on a sticky note. Using our previous example, your stickies might say things like:

- AI has been used in other industries to answer simple phone calls.

- Other states have implemented similar programs using AI in Medicaid call centers.

- Our contact center staff is working overtime.

- 30% of our calls could be answered by AI.

- Using AI would allow our staff to answer the calls that need human intervention, and they wouldn’t have to work overtime.

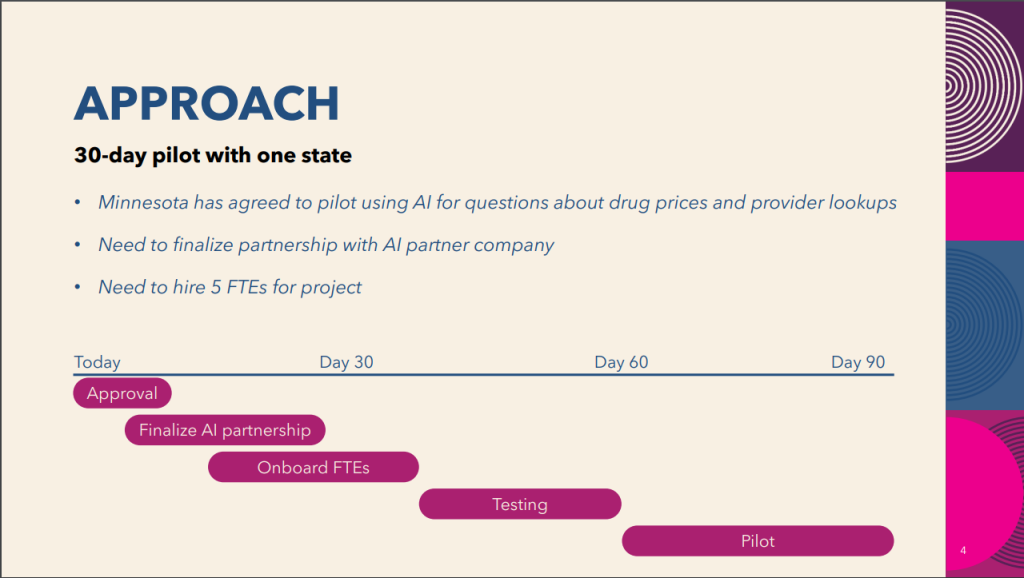

- We will need to hire 5 new people for this project.

- We will need to partner with an AI company.

- A pilot will allow us to test using AI on a subset of our calls.

- Our current cost per call is $10, which is above the industry average.

- Using AI could lower our cost per call to $7.50.

Then, you organize your stickies into themes, which become the main points of your presentation. For example:

Problem

- Our contact center staff is working overtime.

- Our current cost per call is $10, which is above the industry average.

Solution

- AI has been used in other industries to answer simple phone calls.

- 30% of our calls could be answered by AI.

Approach

- A pilot will allow us to test using AI on a subset of our calls.

- We will need to hire 5 new people for this project.

- We will need to partner with an AI company.

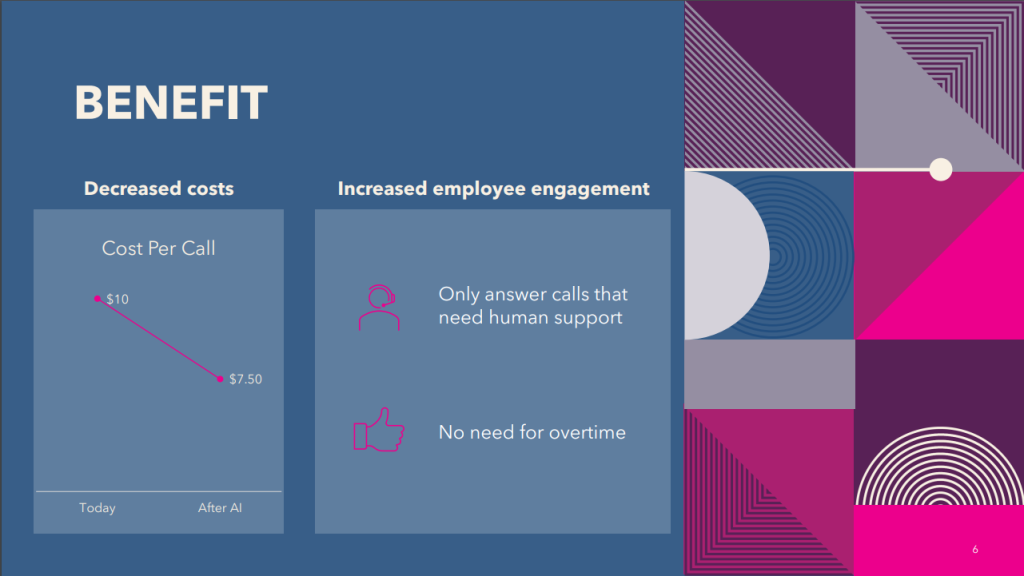

Benefit

- Using AI would allow our staff to answer the calls that need human intervention, and they wouldn’t have to work overtime.

- Using AI could lower our cost per call to $7.50.

Design your visuals.

Now that you have the basic outline of your presentation, you consider what visuals will accentuate your main points and help your audience understand your message. Slides can be much more than a few bullet points. Most presentation applications have a robust set of icons that can help represent an idea with an image. You can also use charts and graphs to display data or financial information. Generally, when you are designing slides, less is more. Poorly designed slides have too many words, repeat what you said verbally, or are so busy that they detract from your message. Think about how the slide will enhance what you are saying.

Figure 7.7: A sample presentation based on the example described above

Practice your delivery.

Now that you have your slides drafted, you figure out what you’ll actually say during each slide. Sometimes it is helpful to write a script just to get your thoughts onto paper. Effective presenters don’t usually memorize or read from a script, as that delivery can come across as robotic, but starting with a script is a good way to initially brainstorm your “talk track.” You can also write a few bullet points per slide to remind yourself of your main speaking points.

Then you practice, practice, practice. You want to ensure that your presentation fits within the allotted time and that you are confident and prepared. Practice in front of a mirror, with a friend, or record yourself. Watch out for any distracting physical movements, filler words (like “um”), and casual language (like “kinda”). It is also a good idea to consider what questions your audience may ask and how you will answer. After a few practice sessions, you’ll be ready to go!

7.8 Why do you write?

Karin Lund

Figure 7.8: Karin Lund ‘12 is AVP of Transformation Initiatives at Prime Therapeutics. Originally from Idaho Falls, Idaho, Karin worked for the Minnesota Attorney General’s Office and worked as a Government Programs Liaison at Blue Cross and Blue Shield Minnesota before joining Prime Therapeutics in 2020.

As I finished my political science major at Gustavus, I was pretty sure I’d go to law school after working for a year or two. Today, 12 years later, I lead large-scale transformations in the healthcare industry—not quite the same as life in a courtroom like I had pictured.

I got into healthcare by accident. My first job after college was at the Minnesota Attorney General’s office, and after a few months, my boss handed me the Minnesota Statutes that pertain to healthcare and told me I was going to mediate healthcare issues for Minnesota consumers. At that time, I didn’t know a lot about the healthcare system, but I certainly learned quickly. I loved the complexity of all the different players that make up the healthcare industry from insurance companies to physicians to pharmacies to hospitals. Most of all, I loved helping people when they were trying to heal and get well. I soon realized that when people are interacting with the healthcare system, they are often experiencing some of their most stressful and vulnerable moments. Our healthcare system is complicated and not especially patient friendly. I wanted to change that.

I went to the University of Minnesota and got my master’s degree in healthcare administration, so that I would have the skills and knowledge to be a leader in healthcare. And that’s where I am today!

In my current job, I don’t do a lot of traditional writing like memos or briefs, but I heavily leverage my writing skills for executive presentations. A critical part of my job is convincing c-suite leaders or boards of directors to invest in a transformation project—efforts that I think will make our healthcare system better. I’ll typically have 15-20 minutes and 3-5 slides to make my case. While the final presentation is brief, the work that goes into it is significant. This is where the writing part comes in.

Let’s say we are recommending acquiring a company. First, I’ll work with a team to do research. We’ll ask ourselves lots of questions and collect pages and pages of information. Sounds similar to starting a research paper, doesn’t it? Then, we’ll synthesize all of that research into a few main themes. By this time, we’ll be forming our main argument or our thesis statement, if you will. We’ll have something very succinct like, “We recommend purchasing this company because it will fill a need in our organization while advancing our corporate strategy and increasing our profits within three years.”