3 Why Are We Talking About This Now?

How can we understand the timing of policymaking?

This is a chapter about the timing of policy making. There are lots of issues on which the government can act, but while the government can do a lot at one time, it can’t act on everything at once. This leads to the question of why certain items are under consideration by the government at a given time…and why others are not. The main point I hope to convey in this chapter is that the things that the media or government are talking about and acting on aren’t random or accidental; rather, there’s a pattern and a process behind the issues of the day. In this chapter, we’ll explore two theories that attempt to explain the timing of policy making and policy discussions: John Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework and Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones’ Punctuated Equilibrium Theory. The Multiple Streams Framework focuses primarily on the stages that lead up to a policy decision, while the Punctuated Equilibrium Theory seeks to explain both the periods of stability that characterize public policy most of the time and the periods of major change at certain points in time.

Multiple Streams Framework

John Kingdon outlined the Multiple Streams Framework in a 1984 book.[1] The MSF seeks to explain why and how issues become things that policymakers pay attention to and act on. Before we can begin to explore these questions, there are two concepts that we need to understand: problems and agendas.

Bad, unpleasant, and annoying things exist all around us, but not all of them rise to the level of being a public problem worthy of the government’s attention. Kingdon refers to these conditions as opposed to problems. A more intuitive way might be to think of them as public problems (as opposed to personal problems). As Kingdon puts it, “there is a difference between a condition and a problem. We put up with all kinds of conditions every day, and conditions do not rise to prominent places on policy agendas.”[2] There are four factors that help move something from the “condition” category to the “problem” category. First, problems violate important values such as justice, equality, or liberty. Something that is just annoying, might bother me without violating an important value. Second, problems must affect a substantial number of people. What qualifies as “substantial” depends on what level of government we’re talking about and how those people are distributed. Something affecting 100 people would be substantial if those 100 people all lived in the same small town but not if they were spread out across the entire country. There’s no magic number when it comes to what makes it substantial, but in general, if more people are affected by something, it is more likely to be defined as a problem rather than as a condition. Third, problems should have a clearly identifiable cause and that cause can’t just be random. Finally, problems should have a possible governmental remedy or solution. If government action can’t fix or at least ameliorate the situation, then it’s less likely that we will think of something as a problem. Thus, a public problem is something that violates important values, impacts a large number of people, has a clear cause, and can be addressed by government intervention.

There are a lot of topics that can clearly be described as political problems: the maintenance of roads and bridges, undocumented immigration, or guidelines for gun ownership. However, there are many topics where there is disagreement about whether the topic is a condition or a problem. Take, for example, the high rates of pollution within communities of color. Some argue that this is a personal problem related to where individuals have chosen to live and where businesses have chosen to deposit waste. Others argue there is a pattern to environmental disparities that goes beyond individual life choices, one that disproportionately affects minoritized communities.

The first stage of the process of getting the government to take action is to ensure that the government believes the topic is worthy of government attention. While some issues are clearly within the purview of government action, policy actors play a major role in convincing both the public and government actors that other issues are also worthy of government action. Their goal is to define the condition (or personal problem) as a problem (public problem), which moves the issue onto the systemic agenda. Roger Cobb and Charles Elder define the systemic agenda as “all issues that are commonly perceived by members of the political community as meriting public attention and as involving matters within the legitimate jurisdiction of existing government authority.”[3] The systemic agenda is a discussion agenda, or the items that actors view as important in public life. There will be different systemic agendas for the different political communities. Your state has a systemic agenda which varies from that of other states.

Figure 3.1: Agenda levels

Being on the systemic agenda is only the first stage, though. The next step is to move the issue onto the institutional (or governmental) agenda. The institutional agenda is the list of topics to which a particular institution is paying attention at any given point in time. Cobb and Elder define it as “that set of items explicitly up for the active and serious consideration of authoritative decision-makers.”[4] These are the list of items about which government actors propose and debate bills, regulations, and opinions. An institutional agenda is smaller than the systemic agenda because the government doesn’t have the time or resources to address every issue.

The final level is the decision agenda. The decision agenda is the list of items that are about to be acted upon by governmental bodies. When Congress or a state legislature debates and votes on a bill, that policy is part of the decision agenda. The decision agenda is even smaller than the institutional agenda.

I find it helpful to think of agenda levels as a set of concentric circles with the systemic agenda as the largest circle and the decision agenda as the smallest. Although the systemic agenda is virtually limitless, there is a limit to the agenda space at the institutional and decision levels because government actors are limited in time and resources. This means that there is going to be some competition over what issues get pushed into the next level. Different actors may have different goals when it comes to agendas. Actors who are in positions of control, might wish to keep items off of the institutional and decision agendas because they are satisfied with the status quo. Actors who want change will seek to push issues on to the agenda and further into the center of the agenda circle. Because there are multiple venues (remember federalism and the separation of powers), these battles over agendas are occurring in lots of different places (state legislatures, the federal court system, etc.).

Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework is built to explain the conditions under which problems move on to the institutional and decision agendas. As you recall, the goal of a policy theory is to call our attention to certain key elements of the process. Kingdon does this by directing our attention to, what he terms, the three streams of the process: Problems, policies, and politics.

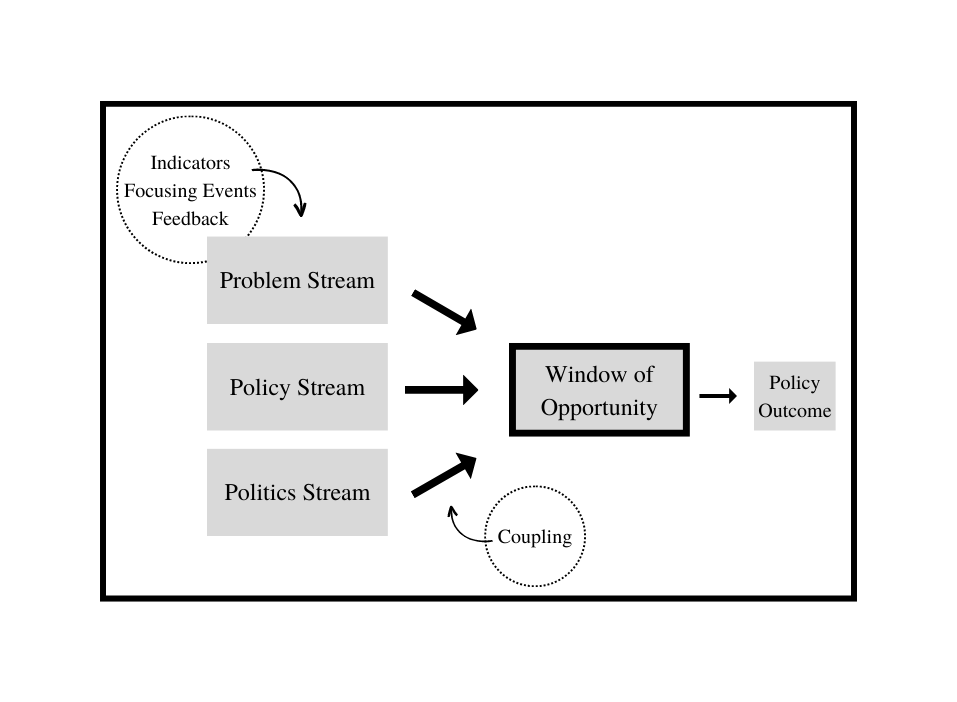

Figure 3.2: Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework

In the problem stream, conditions come to be defined as problems worthy of government attention. Kingdon outlines three primary ways this happens: indicators, focusing events, and feedback. Indicators are pieces of data that are used to measure the size and scope of the problem. An example would be statistics related to the federal poverty level, which can tell us how many people in the United States earn incomes that place them above or below the level of income we deem as living in poverty. Indicators help us make comparisons either over time or between two groups. This helps us make the case that something is getting better or worse…or just staying the same.

Focusing events are major events that draw attention to a problem. A focusing event might be a natural or human-caused disaster like a hurricane or a terrorist attack, but in any case it has to have a cause that is amenable to government action. Sometimes there is debate over whether or not a problem is amenable to government action. For example, after Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005, there was a lot of debate over whether the resulting destruction was an unforeseen act of God, or whether it was the result of faulty work by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in building and maintaining the levee system that failed to prevent flooding or predominantly poor and minority neighborhoods.

Feedback is information that official actors receive from either formal or informal sources. Formal sources include routine monitoring of programs that result in an oversight report or legislative testimony from an agency leader about the workings and effectiveness of a given program. Informal feedback comes from constituents when they call or send letters to elected officials.

In order for policymaking to happen, a topic must be viewed as a public problem by decision makers and so defining a situation as a problem using indicators, focusing events, or feedback is a key step in the policy process. Both official and unofficial actors play an active role in doing this.

The next stream is the policy stream. This is the world of policy ideas that exists in, what Kingdon terms, a “policy primeval soup” in which “many ideas float around, bumping into one another, encountering new ideas, and forming combinations and recombinations.”[5] Kingdon’s point is that there are a lot of policy ideas that exist long before some conditions are ever defined as problems. These ideas are developed by both official and unofficial actors, in and out of government. Kingdon points out that many of the people behind these policy ideas are hidden from the general public, but that they are often well known within “loosely knit communities of specialists.” (This sounds a little like issue networks, doesn’t it?)

Think tanks, research institutions, bureaucratic agencies, and congressional staffers play a big role in this part of the process because they help develop some of the policy ideas that eventually emerge as formal proposals. One of the big roles that actors who are involved in the policy stream play is in narrowing down the list of viable policy alternatives. Sometimes the ideas are pretty extreme on either end of the spectrum, but as they continue to bump around among policy actors, the ideas start to seem more mainstream. Kingdon calls this “softening up”.

The final stream is the politics stream. Here, Kingdon draws our attention to aspects of the political environment that influence how issues move on or off the agenda. These aspects include the result of elections and the national mood (how people are feeling about ideological approaches in general). An election that brings unified control of government (where one party controls both chambers of Congress and the presidency) brings a different set of dynamics compared to one which results in divided government.

These three streams (problem, policy, politics) operate independently until political actors do the work to join them together. Kingdon calls the merging of streams “coupling.” A coupling of all three streams gives an issue the best chance of moving on to the decision agenda. Items that move on to the decision agenda have a brief block of time, a window of opportunity, in which policy action could occur. Some windows open at predictable times; the first 100 days of a new president’s term is a common window of opportunity. Other windows are unpredictable and related to changes in the problem stream or the politics stream. Windows are only open for a short period of time and Kindgon isn’t clear about what this time frame might be.

According to this theory, people who are interested in policy change must be aware of the problem, policy, and politics stream and work to bring them into alignment. This might mean having a policy proposal ready to go so that when something happens in the problem stream (a focusing event, for example), and when the political conditions are favorable (strong public opinion, for example), they can make their case to government actors that their preferred policy alternative is the best solution to the problem.

As a policy theory, Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework helps to draw our attention to three important aspects of the process. Analyzing the policymaking process using this framework means that we need to pay attention to the things happening in the problem stream that bring an issue to the attention of policymakers. It means that we should consider the policy ideas that are already in existence, even long before the current focusing event occurred. And it means that we should pay attention to the political environment. Policy actors who are skilled at joining all three streams are likely to find success in moving their issue on to the decision agenda. Their window for action might be small, but it’s there.

The MSF helps us make sense out of things like the flow of news following a disaster or the speed of the policymaking process at some points. Why, after a mass shooting event, are there always people on television talking about sensible gun control or arming teachers? How is it that Congress was able to draft and pass a 342-page bill just 45 days after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks? The MSF isn’t as helpful with predictions. It can’t tell us when a policy window will open or how long it will remain open. It can’t explain why coupling doesn’t always lead to policy action.

Punctuated Equilibrium

Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones developed the theory of Punctuated Equilibrium to help explain what they observed looking back at decades of U.S. public policy history: most of the time, public policy in the United States is relatively stable, but occasionally, it changes dramatically.[6] To put it in the terms of the theory, most of the time U.S. policy is characterized by an equilibrium (balance) but marked by punctuations (think exclamation points!) of major change. The Punctuated Equilibrium Theory helps explain periods of policy stability and predict when major change is likely to occur by focusing on the “politics of attention,” or the competition between issues.

According to the theory, two factors shape the context for policymaking: boundedly rational decision-making and political institutions. Let’s break these concepts down a bit. If asked, I would guess that most people would say they are rational decision makers, meaning they make decisions based on information and logic. In the field of public policy (and economics), the term rationality has a specific meaning, so let’s take a moment to explain it. A comprehensively rational decision is the ideal type of decision because it is based on logic and evidence. In order to make a rational decision, the decision maker must 1) have access to and be able to understand and process all of the relevant information related to a decision, 2) be able to identify and rank their values and preferences, and 3) be able to evaluate the information in light of those preferences in order to arrive at the best possible decision.

This method of decision making sounds great in theory, but there are several problems with it. First, there are a lot of limitations on information. Decision makers might not have access to all relevant information or information they access may be inaccurate. Even when they have access to lots of information, they may not be able to sort through it all or understand its implications correctly. Second, it can be very difficult to identify and rank values and preferences. Often values conflict (think security versus liberty) or the context of the decision matters. Finally, this model doesn’t reflect reality very well, because we know that people make decisions that go against their preferences or interests all of the time.

Herbert Simon, an economist, pointed out these flaws in the rational model of decision making and argued that a more accurate way of understanding decision making would need to include some of the constraints under which decision makers operate. The approach that resulted from his work, Bounded Rationality, recognizes that decision makers have cognitive limitations related to both attention and emotion. Most importantly, individuals have a limited attention span. There are only so many things a person can pay attention to at any given time. In a world of information overload, we learn how to block some information out altogether and how to use mental shortcuts (called heuristics) such as taking cues from sources we trust. In addition to our limits in attention, we are also heavily influenced by our emotions. When we feel scared we make different choices from when we are feeling secure. These cognitive limits in attention and emotion are key to understanding the timing of policymaking.

Punctuated Equilibrium Theory recognizes that it’s not only individuals who make decisions with these limitations (bounds) but government institutions also operate under bounded rationality. This relates to the concept of agenda space we discussed earlier. There is only so much room on an institutional agenda and there is even less room on a decision agenda. However, because there are multiple venues (remember that term from chapter 2?), there is a bit more space to work with than with an individual. Each venue still has a limitation to its attention span, though. And, similarly to individuals, government institutions are influenced by emotion and attention.

Given these limitations in decision making for both individuals and institutions, the ways that issues are defined and the process of moving them on to the agenda become very important. This brings us back to the politics of attention. In the political system, some issues compete for the attention of policymakers while other issues work to avoid attention altogether. When issues avoid attention, change is limited and incremental. When issues gain attention, change can be explosive and sudden.

The battle for attention (or non-attention, in some cases) happens within a system that is designed to be very stable. The separation of powers between the three branches of government (with many overlapping powers) and the federal system that divides government powers between the national and state levels both slow the process down. The next chapter will provide more detail about the process it takes to enact a new policy, but for now, it’s enough to know that the American political system is very resistant to change.

Within this context, policy monopolies develop, what Baumgartner and Jones call subsystem politics. Policy monopolies are responsible for policymaking in one issue area. The actors in a policy monopoly who control policymaking of one issue are supported by a policy image, another way of saying the way the problem is defined. In other words, there is a dominant way that the public and policymakers think about the issue. Because all of the interested actors share that definition of the problem, there is little incentive to change the way the problem is addressed.

Policy monopolies insulate themselves by being specialized and developing norms of keeping conflict within the group. The actors within the policy monopoly bring expertise to the topic and generally try to keep the policy as technical and boring as possible because this helps keep the public disinterested. When actors within the policy monopoly have different opinions, they try to work them out within the group itself rather than expanding the conflict to a wider group because that way they know who they’re working with and what they’re working against. The uncertainty that comes when you bring new people into a conflict incentivizes policy monopolies to work out their differences internally. Different policy monopolies develop a policy of non-interference with other policy monopolies, deferring to their leadership over other issues and expecting deference in return.

Figure 3.3: Baumgartner and Jones’ Punctuated Equilibrium Theory

The stability of the system and its resistance to change, coupled with a stable set of actors and a shared policy image results in policymaking that is slow and incremental for long periods of time. For example, the budget for an existing program might be increased every few years to account for inflation or might be tweaked in small ways to adjust to new conditions. The same group of policy actors will be involved in making these minor changes.

To this point, we have thought about the equilibrium stage as maintained through policy monopolies, but pluralist theory suggests that it can also be maintained through an equal balance of group interests. In other words, another way to maintain equilibrium in the system happens when there are two firmly entrenched sides in the debate that wield approximately equal power to the point where policy decisions are relatively gridlocked.

Occasionally, though, the balance of power changes resulting in major policy changes (punctuations). Baumgartner and Jones call this macro politics.[7] The key factor that leads to change is the way the issue is defined, or a change in the policy image. Issue definition is about how a policy is described or understood. When this definition changes or when it becomes contested, it changes the politics of the debate and shifts the attention of policymakers.

So what factors lead to a change in an issue definition? Punctuated Equilibrium Theory identifies both external techniques and internal changes that affect issue definition. External techniques are used by actors to shape policy images and drive attention. Internal changes happen within individual decision makers.

Let’s start with external techniques that impact issue definition. The first technique is issue framing, which involves how the issue is defined as a problem. For each issue, there are multiple ways of approaching it based on a person’s values, goals, and preferences. There are different aspects of the issue that a person might want to emphasize or downplay given their preferences. There might be different explanations for what caused the problem or different ideas for what an appropriate solution might be. All of these factors go into the framing process. Interest groups and political parties play an important role in this part of the process because they work hard to frame issues in a way that supports their preferred policy outcomes.

One of the most important approaches interest groups and political parties use to develop their preferred framing of an issue involves seeking out media attention. Groups might stage events to gain coverage on the nightly news or run advertisements to shape the public’s understanding of an issue. The goal of these activities is to get people to think about the issue in a different way…or even to think about it at all. Getting back to the Multiple Streams Model, the goal is to move the issue on to the institutional agenda, but in a way that highlights their view of the issue. Actors use both empirical information (facts, research, etc.) and also emotional appeals to portray their preferred view of the issue. This shapes, or frames, the topic in a specific way that will ideally mobilize more people to join their cause.

Policy actors can often take advantage of focusing events in their framing attempts. A focusing event has the advantage of already drawing media attention, and a clever policy actor might be able to link their preferred framing to the event. Remember, though, that these policy images are generally contested. Even a focusing event won’t always lead to everyone agreeing on the nature of the problem (think back to the school shooter example).

A second external technique is called venue shopping. In short, groups strategically seek out more favorable venues for action. If there is a policy monopoly on an issue at the federal level, they might look to pursue change at the state level. If the legislature seems unlikely to budge, they might pursue a legal strategy. The venue itself might even become a part of the frame as policy advocates make the case that the issue ought to be decided in a particular venue. When pursuing this approach, groups might engage in mimicking, or copying a successful strategy from other policy areas in a new issue. A group concerned about gender bias, for example, might copy the approach of previous efforts related to bias based on race and ethnicity.

Venue shopping can be effective for two reasons. First, it allows the policy actors to shift the debate to a context in which it will be easier for them to draw the attention of the policy makers. Issues at the federal level compete with an overwhelming number of other issues, but the competition is reduced at smaller levels of government. The calculation here is about which venue will provide the easiest access, knowing that agenda space is limited and policymakers can only pay attention to a certain number of issues at once. Second, venue shopping is related to framing in that certain venues are more receptive to certain frames. An ideologically conservative frame will be more appealing to a venue that is dominated by ideological conservatives. A frame that emphasizes constitutional rights might be more successful in a legal venue than in a legislative venue, where actors care strongly about reelection.

Both of these techniques–framing and venue shopping–involve changing the attention paid to the issue, which we know is in limited supply, and changing how we think and feel about the issue.

In addition to these external techniques to shape attention and emotion, there are internal changes that can happen affecting individual decision makers. First and foremost, individual decision makers can change their preferences. This may come about because a decision maker encounters new evidence. Individual official actors are people too and they have experiences that can profoundly impact their beliefs and values. Think about what happens when an ideologically conservative person finds out that their child is gay or what happens when an ideologically liberal person is a victim of a violent crime. People do change their preferences based on personal experiences. Of course, the new evidence could also be empirical evidence resulting from research, but this is often less impactful than personal experience (another reason bounded rationality is a more accurate approach to understanding decision making behavior than classic rationality).

It can be very difficult for policymakers, particularly those who are elected, to change their preferences. In politics, people who change their minds about an issue are often attacked for it in campaigns. This is unfortunate because changing your mind in response to new information is the definition of learning, and it seems like that is something we should encourage rather than scorn.

Second, individual decision makers are also subject to changes in attention. With this, it is not that the decision maker is changing their mind about an issue, but rather that it’s just not the most important issue at the time for them. If you think about an individual candidate running for office, they usually outline a platform of their positions on a few important issues. These are obviously not the only issues on which they have opinions, but they are the issues they consider important at the moment. Similarly, once in office, they make choices about which issues to devote their limited resources (time and staff). This list of issues might change based on what is happening within the larger political environment.

Finally, individual decision makers themselves can be replaced, with the new decision makers holding different preferences than their predecessors. This makes the time period following elections particularly ripe for major changes.

The changes that happen within individuals and the techniques used to shape the system help to explain the timing of major policy change. Most of the time, we should expect very minimal changes to policy, an incremental approach. This is because the system is set up to resist change and because policy monopolies further reduce the likelihood of change. But when actors are successful in changing the attention of institutions and individuals through providing an alternative policy image, rapid change can occur quickly. The Punctuated Equilibrium framework has been empirically tested using decades worth of data in the U.S. and in other countries and the pattern of long periods of stability followed by short bursts of activity is remarkably consistent.

What do these theories tell us about timing?

The Multiple Streams Framework and the Punctuated Equilibrium Theory give us insight into the dynamics that help us understand the timing of policy decisions. Issues don’t just pop up randomly; rather, actors work strategically to shape the way we define issues and problems and to move those issues on to the agenda of policymakers. One common claim between these two theories is that policy problems aren’t inherent, but that they are socially constructed by policy actors. Social construction means that the policy actors give the problem its meaning and worth and policy actors are responsible for highlighting some issues as worthy of government attention while keeping other issues relatively obscured. Reading that sentence might send you straight into the elite theory camp, but remember that the policy actors represent a range of players, from elected officials to interest group leaders to the general public.

The big point is that the timing isn’t random; It is predictable and strategic. A perfect policy window might not always result in policy, but policy doesn’t change without the conditions outlined by these two theories. If we want to understand the policymaking process, we need to pay attention to the process that brought, or might bring, the issue to the forefront of the agenda and remember that there are actors behind that effort.

Figure 3.4: The first 100 days of a new president’s term are usually considered a big policy window. Here are some Gustavus students attending the inauguration of President Donald Trump in January 2017.

In preparation of pushing an issue onto the agenda, policy actors need to know a lot about the topic. Behind the scenes, interest groups, think tanks, political parties, and government staffers take time to research different topics so that they are prepared to act when the right moment arises (or so that they are prepared to create the right moment themselves!). Because there are so many issues out there, the people who actually make decisions don’t always know a lot about the topics. Instead, they rely on information provided to them by their staff or other interested groups. One common vehicle for this information is a briefing memo.

What is a briefing memo?

There are several variations of a briefing memo common in the field of public policy. All of them share the common characteristic of attempting to summarize large chunks of information for a particular audience. Briefing memos range in length. There are a few examples of documents that fall within this category in this book, like the sample bill summary shown in chapter 2 and Appendix A or the sample event memo shown in in Appendix D, which are examples of short briefing memos. The purpose of the bill summaries is to briefly summarize bills for legislators while the purpose of the event memo is to help prepare an elected official for a public event. Legislative briefing memos also include the longer, more detailed reports published by the Congressional Research Service.[8]

In this class, we practice the skills needed to write different types of briefing memos through a policy history assignment. A policy history, sometimes called a legislative history or a regulatory history, is an informative, research-based document that provides a specific decision maker with information and context for an impending decision by offering a clear and concise explanation of how the government has addressed a problem through legislation, regulation, and/or judicial ruling.. Policy histories are often written by staffers working for elected officials, bureaucrats, or interest groups. Depending on the policy/issue in question, a policy history may involve one or more levels of government (federal, state, local) and one or more jurisdictions (legislature, executive, judicial).

The audience for a policy history is generally a specific decision maker or group of decision makers who request information needed to address a particular issue. These individuals are very busy and so they don’t have time to learn everything about every issue. But, they need high quality information in order to be able to make a decision. An effective policy history provides a decision maker with the high quality information they need in the brief format they have time to digest. For example, a Member of Congress may want to know about previous efforts to prevent hate crimes before proposing a new measure or a governor might want information about how other states have addressed the question of whether to issue driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants. As both of these examples suggest, a policy history is usually written for a specific audience and with a specific purpose in mind. The governor in the example above doesn’t want an essay about immigration policy in general, she wants a summary of very specific information that will allow her to make informed policy decisions. Having a clear sense of your audience and the purpose of your task is the first step to take in writing a good policy history.

Unless the person asking for the policy history specifically requests that the writer recommend a course of action, the goal of a policy history is generally informative rather than persuasive. The job of the author is to provide the decision maker with accurate, timely, and relevant information so that they are able to make an informed decision. This doesn’t mean that the writer can’t or shouldn’t have a perspective on the topic, but it does mean that that perspective shouldn’t be the main message driving the writing and it shouldn’t interfere with accurate reporting. You don’t want your boss blindsided because you only focused on one side of an argument and didn’t give them enough information about the other sides.

Once you have a clear sense of your audience (who has asked for the policy history?) and purpose (what do they want you to find out?) it’s time to think about the scope of your research and to begin to do the research itself. You’ll need to know whether you are looking for information about federal, state, or local policy and whether you are interested in legislation, regulation, judicial decisions, or something else. You’ll also need to know something about the time frame. Are you trying to provide information that covers a long period of time or actions that are more recent?

Based on your answers to these questions, you should begin the research process by locating any relevant policies or proposals and information about those policies.

First, you need to provide a general understanding of the issue or conflict. What is the policy problem being addressed in the policy history? You need to be able to summarize this issue within a paragraph.

Second, you need to provide a summary of government responses to the problem. This means looking at existing laws or past policy proposals, bureaucratic rules and regulations, or court decisions. Doing this research is a lot like doing detective work as you try to track ideas through the policy process. You will find online databases like congress.org or federalregister.gov to be particularly helpful. Depending on your audience and their needs, you might be focusing your research on the federal level or at the state level.

Third, you need to provide your audience with information about key actors in this debate and their main arguments. The point in this type of writing is not to “pick a side” in the debate, but rather to make your audience aware of the key players and arguments. This also involves some detective work, as it may involve consulting news articles, congressional floor speeches, hearing testimony, or interest group websites.

The goal in this stage of the process is to learn about the problem, the policy solutions (or proposed solutions), and the key actors so that you can summarize this information in the policy brief. This part of the process should feel very familiar to you if you are used to doing academic research. But rather than looking for peer reviewed sources (like books or journal articles), as is common in academic research, you will focus on finding sources that help you understand the issue’s context and the policymaking process. This means that you might rely on primary sources (like the policy itself or other government documents) and sources that aren’t peer reviewed (like news articles, press releases, and websites). You are still responsible for using quality sources even if those sources aren’t the same as the ones you would use for an academic research paper.

One of the biggest challenges is that you are likely to learn a lot of information through your research but your audience does not have time to read or digest all of that information. You will have to make decisions about which information is most important to share and most relevant to the task at hand.

Once you’ve done all the research necessary to be able to summarize the issue, existing policy efforts, and key players and arguments, you’re ready to start writing.

A policy history generally takes the format of a long memo crossed with a research paper. It begins with the standard memo opening lines (date, to, from, subject). Your subject line functions as a title and should provide clear information about the content of the policy history. You should use subheadings within your policy history to help direct your reader to the different sections of the memo.

You have many options when it comes to organizing a policy history and the method you choose should reflect the specific purpose of the document. One method is to organize your policy history chronologically. This works well if you are summarizing the development of an issue or policy over time. A second method is to organize by policy. This works well if you are comparing multiple policies or are presenting multiple proposals designed to address a particular policy problem. A third method is to organize the policy history according to the most significant developments. This might mean picking out a few key policy decisions or actions. A fourth method is to organize the policy history topically. This works well when you are dealing with a large issue that has natural subtopics. Finally, you could organize the policy history by jurisdiction. This method is useful when you are covering actions taken in different jurisdictions (i.e. legislative, regulatory, and judicial). The method of organization you pick should help you achieve the purpose of the task.

Stylistically, a policy history should be succinct and clear, without flowery language or embellishment. Because you’ll be summarizing some policies, remember that you should write out the full policy name the first time. You can abbreviate it in later mentions.

Because a policy history is a research-based paper, it is important that you provide citations for all of your sources. Footnotes are a useful way of citing sources because they don’t distract from the prose the same way that in-text citations do but they still allow your reader to find the information. Be sure to use a citation guide to produce your bibliography.

Your finished product should provide a clear overview of the topic and be easy for your audience to skim through. It will probably be longer than a memo but shorter than a research paper (in the 2-10 page range). It will look like a memo, but will include a bibliography like a research paper. It will be targeted to a specific audience and written for a specific purpose.

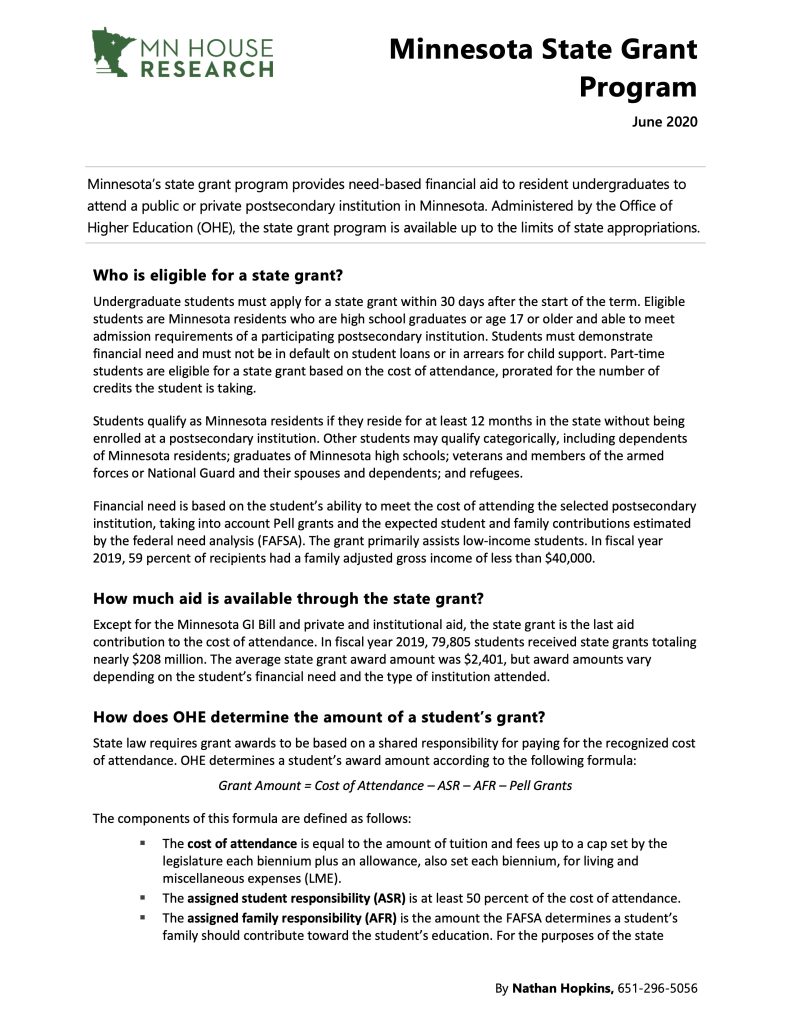

Take a look at this sample policy brief. Can you spot the stylistic markers that make it a policy brief? Who wrote it and for whom is it written? Can you make an educated guess as to what task the writer was asked to do? How did the author organize the document?

Figure 3.6: Sample Policy Brief

Why do you write?

Figure 3.7: Kaleb Rumicho ‘09

My name is Kaleb Rumicho. I was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and moved to Minneapolis when I was a child. My family and I immigrated to the U.S. as political asylees. So I grew up in a multilingual and multicultural home and community, where I had the privilege of observing and learning from all types of people and being immersed in domestic and international politics. Because of my lived experiences, I was fascinated by psychology, politics, and the law. When I attended Gustavus, I naturally majored in psychology and minored in political science with the goal of attending law school immediately thereafter. I recognized how powerful the U.S. legal system is compared to many countries around the world, and discovered that the law here is deeply rooted in political, economic, and social dynamics. I saw how the power of the law here changed my family’s destiny. In turn, I knew that pursuing a legal education was the best way for me to have an impact in my community.

After graduating from Gustavus, things did not turn out as I had planned. The economy collapsed. Many advised me not to pursue law school because there were too many lawyers and not enough jobs. Instead, mentors advised me to pursue another career or passion. After some soul searching, I decided to go into education then government and politics before ultimately pursuing my legal education at Howard University in Washington, D.C. and fulfilling my longtime goal. The experiences, the skills, and the relationships gained between undergraduate and law school were incredibly helpful to me during and after law school and made me appreciate the unexpected—or at least not to be afraid to deviate from my plans.

While my current position does not expressly involve public policy, the writing skills or process are still very similar and applicable. Currently, I am a corporate lawyer at an international law firm. In my role, I represent public and private companies on transactional and corporate law matters, including domestic and cross-border mergers and acquisitions. In other words, I—along with colleagues—represent clients where we advise, conduct due diligence, and draft and negotiate transaction agreements and ancillary documents, all related to the buying, selling, or merging of companies. There is a lot of drafting and paperwork in this line of work. The writing is more technical or legalese than it is creative. As such, attention to detail and word precision on any given document is vital to effective client representation. Further, I write many emails, memoranda, and other forms of correspondence, using similar, if not the same, process and approach as I did when I held various government roles.

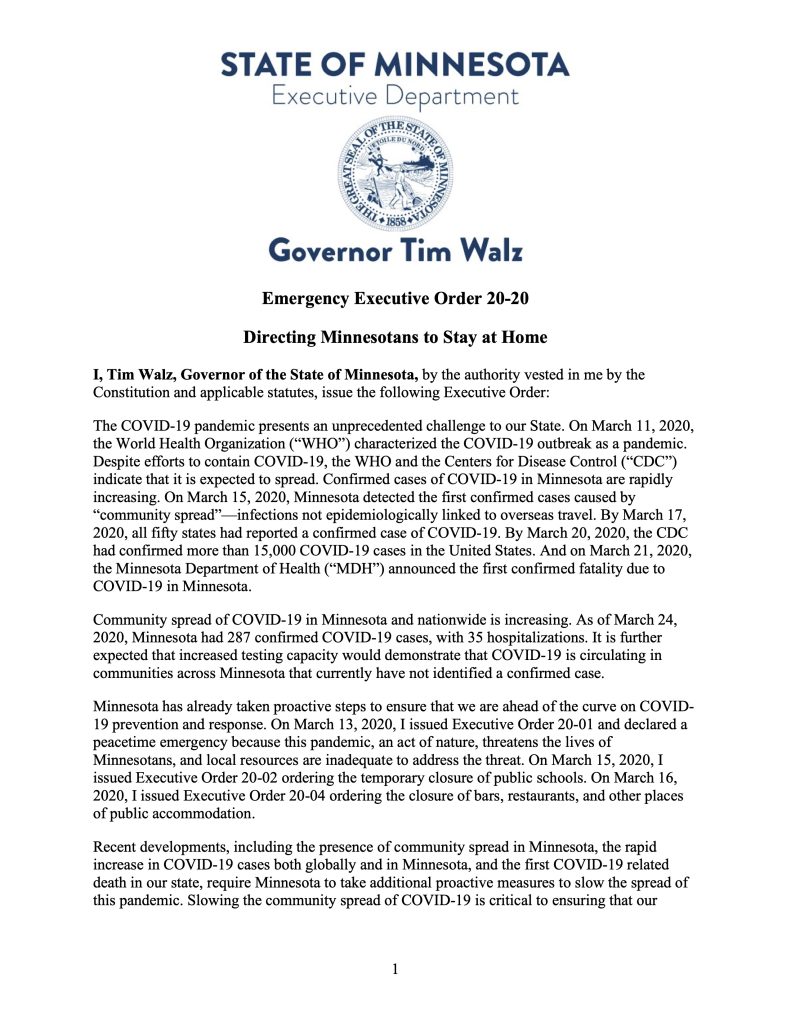

I previously held various positions in the public policy arena. Before law school, I worked in various roles for a U.S. Senator. During law school, I worked as a law clerk at the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. In these various roles, I had many opportunities to participate and engage in not just policy issues but also constituent, press, legal, and community-engagement issues. After law school and a couple of years in the private sector, I pivoted to state government, where I served as a legal advisor to the Governor and Lt. Governor of Minnesota during the height of the pandemic. In that role, I advised the Governor, Lt. Governor, and the rest of the Governor’s office on legal matters, including researching and writing on substantive legal issues and providing advice related to statutory interpretation. I provided legal advice on the Governor’s various authorities and executive orders. I advised on the legal response to the COVID-19 pandemic and social unrest—including drafting many of the earlier COVID-19 executive orders. I also oversaw the judicial appointment process for state appellate and district courts and executive branch courts.

In my role with the Governor’s office, I wrote a variety of things—legal memoranda, briefings, letters, press releases, speeches, reports, executive orders, etc. These writings, depending on their purpose, ranged from purely informative to persuasive. The recipients of these writings ranged from the Governor, Lt. Governor, colleagues, senior state officials, to judges and justices. No matter the type of writing, it was always backed up by research and facts. It was imperative that each and every work product produced by our office was well-researched and supported by facts.

Figure 3.8: First page of the Stay at Home Executive Order for Minnesota, drafted by Kaleb Rumicho. Click here to read the entire executive order: https://mn.gov/governor/assets/3a.%20EO%2020-20%20FINAL%20SIGNED%20Filed_tcm1055-425020.pdf

The Stay at Home Executive Order was the most consequential piece of writing I’ve done in my life. The Stay at Home Executive Order was the most consequential piece of writing I’ve done in my life. Although I drafted the initial draft and led the process, this wouldn’t have been possible without a number of people—especially my direct boss, the General Counsel—who were intimately involved in the details. I worked with the Governor, Lt. Governor, Chief of Staff, General Counsel, agency commissioners, subject matter experts, stakeholders, policy advisors, and many others to review, to understand the real-life implications of each item in the order, to find ways to mitigate negative consequences, to seek and receive feedback from stakeholders, to review and revise as many times as necessary and to finalize, execute and file this Executive Order. Nobody had a precedent or a playbook on how to respond to the pandemic. At this point of the pandemic, everyone was working together to ensure the safety and security of their constituents. Governors and their staff across the country–regardless of political party–were working and collaborating to ensure that we responded to this pandemic as best as we could. It was a unique and surreal time for many reasons. As you review the Executive Order, note the following: the preamble provides the legal and public policy rationale for the order. This is important in providing context for the “what” and “why” of the order, as well as, outlining the Governor’s authority to enact such order. Provisions 1-2, 7-12 lay out the Governor’s orders (i.e., law per the order). Provisions 5 and 6 lay out the exemptions under the order. When reviewing these exemptions, think about why they were included and what issues or concerns they are intended to mitigate. The other provisions lay out the Governor’s further instructions and rule of law for the time specified in the executive order (until the peacetime emergency declared by the Governor was terminated or rescinded).

As for my writing process, before I begin drafting, I think first and foremost about the objective at hand: the purpose of my writing, the perspective of my audience, and the complexity of the subject matter. This is helpful in organizing my thoughts and formulating an outline. If the purpose is to draft an agreement between two parties who are transacting, my writing will be different than if it is a legal analysis memo answering a specific legal question. Similarly, if my audience are two parties in an acquisition transaction, I have to make sure I reflect all negotiated and agreed upon terms in my draft agreement. But if it is a client who asked a specific legal question, I have to make sure I answer the question directly and provide my research and analysis to support such answer. Lastly, determining the subject matter informs me how much work will need to be put into the writing, thereby helping me allocate necessary time to the task.

Writing is like a puzzle. I note my thoughts, ideas, and, where applicable, research findings in a document. I try to group my notes by theme, issue area, or in some cases, by propositions or arguments that I would like to assert. Once I have the notes and information I need on paper, I open a different document and start rearranging and editing these notes. During this process, I work on the organization and flow of my writing. It also helps me catch items that need further research or discussion, or arguments that need to be reevaluated. Once I complete my first take at the puzzle, I walk away and come back to it later. I review a second time and, almost always, revise. Upon the completion of the revision process, when possible and depending on the confidential nature of the work product, I will ask one or two other people to review and comment. It is always good to get a fresh set of eyes on your work. It makes your work product better. Once I receive feedback, I accept comments that I agree with, review and revise one more time, and then consider it final and send to recipient(s).

Be clear, be concise, and do not bury the lead. The key to any non-technical writing—whether in private practice or public policy—is to be direct, succinct, easily digestible, and sufficiently informative. This is easier said than done. It is more important to make your writing accessible and understandable than long and fancy. Simplicity and clarity are important. People are busy and want to consume information in a quick and efficient manner. They do not have time to read a ten page memorandum when all of that could have been effectively conveyed in one page or less. Throughout my formal education, I have been taught that the more you write, the better; the fancier words you use, the smarter you sound. This may be true if you are writing a dissertation. But in my experience, much of that has not been true in the working world. Throughout my formal education, I have been taught that the more you write, the better; the fancier words you use, the smarter you sound. This may be true if you are writing a dissertation. But in my experience, much of that has not been true in the working world. In fact, most people prefer fewer words and more accessible language. They just want answers.

What comes next?

In this chapter, we explored the question of timing…why is it that we talk about certain issues at certain times but not at others? We reviewed Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework and Baumgartner and Jones’ Punctuated Equilibrium Theory as two tools for understanding the timing of the policymaking process. These theories answer similar questions about the things that have to happen before we can get to the point of policy action.

In the next chapter, we’re going to talk about how policy is actually made; in other words, how do we get from the ideas floating around in the policy primeval soup to actual policy? Much of this information will likely be a review from your last U.S. Government class, but hopefully it will provide a useful refresher of the process.

Questions for discussion

- What are some conditions that are not problems? What are some conditions that have become problems in recent years?

- Think of a focusing event with which you are familiar. In what ways was that focusing event linked to policy proposals? To your knowledge, did the focusing event lead to any policy change? Use the theory to help you explain the outcome.

- Pick an issue that you are familiar with. What are some different ways that the issue can be framed? Have you seen examples of these frames in real life? What actors are behind the different frames?

- Pick an issue that you are familiar with. What venues are most important to policymaking for this issue? Has the issue changed venues at all? What actors might be behind the process of venue shopping?

Glossary

Bounded Rationality: This perspective on decision making recognizes that decision makers have cognitive limitations related to both attention and emotion.

Coupling: The process of two or more streams coming together in the Multiple Streams Framework.

Decision agenda: The list of items that are immediately about to be acted upon by governmental bodies.

Feedback: Information that official actors receive from either formal or informal sources that impacts the policymaking process.

Focusing events: Major, unexpected events that draw attention to a problem.

Indicators: Pieces of data that are used to measure the size and scope of the problem.

Institutional agenda: The list of topics to which a particular government institution is paying attention at any given point in time.

Issue framing: The process of defining an issue as a problem by choosing to highlight or de-emphasize certain aspects of the issue.

Macro politics: Major policy changes.

Mimicking: The technique of copying a successful strategy from one policy issue in a debate over a different policy issue.

Multiple Streams Framework: The MSF seeks to explain why and how issues become things that policymakers pay attention to and act on.

Systemic agenda: Issues that are viewed by members of the political community as meriting public attention and as falling within the legitimate jurisdiction of existing government authority.

Policy image: The way a problem is defined and portrayed to the public.

Policy stream: Part of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework in which different policy ideas exist independently of political problems.

Politics stream: Part of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework in which aspects of the political environment influence how issues move on or off the agenda.

Problem stream: Part of Kindgon’s Multiple Streams Framework in which conditions come to be defined as problems worthy of government attention.

Punctuated Equilibrium Theory: This theory seeks to explain why public policy experiences long periods of stability but can also feature sudden and dramatic changes at certain points in time.

Rational decision: A rational decision is one in which the decision maker must 1) have access to and be able to understand and process all of the relevant information related to a decision, 2) be able to identify and rank their values and preferences, and 3) be able to evaluate the information in light of those preferences in order to arrive at the best possible decision.

Social construction: The process of giving a problem its meaning and worth.

Softening up: Part of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework in which actors become more comfortable with policy proposals. This is especially common when ideas are pretty extreme on either end of the spectrum, but as they continue to bump around among policy actors, the ideas start to seem more mainstream.

Subsystem politics: Policymaking that is impacted by a small and stable group of official and unofficial actors.

Venue shopping: The process of proactively seeking out a more favorable venue for political action.

Window of opportunity: Part of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework. A brief block of time when multiple streams converge to allow policy action to occur.

Additional Resources

Comparative Agendas Project: https://www.comparativeagendas.net/us

Congressional Research Service Reports: https://crsreports.congress.gov/

Legislative Explorer: http://www.legex.org/

- John Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies 2nd Ed (New York: Harper Collins, 1995). ↵

- John Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies 2nd Ed (New York: Harper Collins, 1995), 198. ↵

- Roger W. Cobb and Charles D. Elder, Participation in American Politics: the Dynamics of Agenda Building (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983) pgs 82-93. ↵

- Roger W. Cobb and Charles D. Elder, Participation in American Politics: the Dynamics of Agenda Building (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983) pgs 82-93. ↵

- John Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies 2nd Ed (New York: Harper Collins, 1995), 200. ↵

- Frank R. Baumgartner and Bryan D. Jones, Agendas and Instability in American Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1993). ↵

- The terms subsystem politics and macro politics come from Emmette S. Redford, Democracy in the Administrative State (New York: Oxford University Press, 1969). ↵

- You can search for CRS reports at this website: https://crsreports.congress.gov/ ↵

The MSF is a theory developed by John Kingdon that seeks to explain why and how issues become things that policymakers pay attention to and act on.

Issues that are viewed by members of the political community as meriting public attention and as falling within the legitimate jurisdiction of existing government authority.

The list of topics to which a particular government institution is paying attention at any given point in time.

The list of items that are immediately about to be acted upon by governmental bodies.

Pieces of data that are used to measure the size and scope of the problem.

Major, unexpected events that draw attention to a problem.

Feedback refers to the way the outcomes or effects of a public policy influences the development of new policies or the revision of existing policies.

Part of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework in which different policy ideas exist independently of political problems.

Part of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework in which actors become more comfortable with policy proposals. This is especially common when ideas are pretty extreme on either end of the spectrum, but as they continue to bump around among policy actors, the ideas start to seem more mainstream.

Part of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework in which aspects of the political environment influence how issues move on or off the agenda.

The process of two or more streams coming together in the Multiple Streams Framework.

Part of Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework. A brief block of time when multiple streams converge to allow policy action to occur.

This theory seeks to explain why public policy experiences long periods of stability but can also feature sudden and dramatic changes at certain points in time.

A rational decision is one in which the decision maker must 1) have access to and be able to understand and process all of the relevant information related to a decision, 2) be able to identify and rank their values and preferences, and 3) be able to evaluate the information in light of those preferences in order to arrive at the best possible decision.

This perspective on decision making recognizes that decision makers have cognitive limitations related to both attention and emotion.

Policymaking that is impacted by a small and stable group of official and unofficial actors.

The way a problem is defined and portrayed to the public.

Major policy changes.

The process of defining an issue as a problem by choosing to highlight or de-emphasize certain aspects of the issue.

The process of proactively seeking out a more favorable venue for political action.

The technique of copying a successful strategy from one policy issue in a debate over a different policy issue.

The process of giving a problem its meaning and worth.

Part of Kindgon’s Multiple Streams Framework in which conditions come to be defined as problems worthy of government attention.