5 Why Does Policy Look Like This?

The purpose of public policy is to achieve desired goals by changing behavior. There’s not just one way to get people to change their behavior in a way that achieves your goals, though. Imagine that you are a student in my class who has missed a day of class and wants to get a copy of the notes from a classmate. You have several different options from which to choose: You could ask a classmate for their notes. You could offer to take notes for a classmate for a future day in exchange for their notes from the day you missed. You could demand they provide you with notes. You could threaten to beat them up if they don’t share their notes (I don’t recommend this approach). You could ask me to provide extra credit on the next exam for anyone who shares their notes with you. There are a lot more options, but you get the idea…you have many different ways you could go about getting those notes. Think of these different options as the tools you have at your disposal for achieving your desired goal of obtaining the notes you missed by changing the behavior of a classmate.

In a similar way, policymakers have various tools they can use to get the public to behave in ways that satisfy the goals of public policy. In this chapter, we’ll talk about these different options and introduce a theory that helps explain and predict which options policymakers pick in different situations. The Social Construction of Target Populations, a theory developed by Anne Schneider and Helen Ingram helps to answer the question that frames this chapter: why does policy look like this? But before we get to that, I want to explore two motivating factors that impact policy design: goals and blame.

What goals motivate policymaking?

It probably seems obvious that a major goal in policymaking is to address or alleviate a problem that’s been identified, but as policymakers go about doing that, they also bump into the fact that individual actors have multiple and sometimes conflicting goals which impact the policymaking process by affecting the way policy is designed. Let’s start by identifying some of those goals. Deborah Stone identifies five major goals in policymaking: equity, efficiency, welfare, liberty, and security. Michael Kraft and Scott Furlong add two additional criteria worth mentioning: effectiveness and political feasibility. There are, of course, other goals in play, but let’s briefly focus on these six as a starting point.

Figure 5.1: Seven Common Political Goals

Equity (and its cousin, equality) is a major goal for many in the United States. Kraft and Furlong define equity as: “fairness or justice in the distribution of the policy’s costs, benefits, and risks, across population subgroups.”[1] While this may sound fairly clear cut, Stone argues that it is actually quite complicated. She uses an example of trying to divide up a chocolate cake in her class and identifies nine different ways that the cake could be distributed “equitably” and only one of them involves cutting an equal sized piece for each student in the class.

Equity (and its cousin, equality) is a major goal for many in the United States. Kraft and Furlong define equity as: “fairness or justice in the distribution of the policy’s costs, benefits, and risks, across population subgroups.”[1] While this may sound fairly clear cut, Stone argues that it is actually quite complicated. She uses an example of trying to divide up a chocolate cake in her class and identifies nine different ways that the cake could be distributed “equitably” and only one of them involves cutting an equal sized piece for each student in the class.

Efficiency is about “getting the most for the least, or achieving an objective for the lowest cost.”[2] As Stone points out, though, efficiency really isn’t itself a goal, it is just a means to an end. Nevertheless, when we have a choice between two different solutions, we generally favor the one that is the most efficient.

When Stone talks about the goal of welfare, she doesn’t mean a government program to provide financial assistance to families in need, but rather the general belief that “society should help individuals and families when they are in dire need.”[3] This includes both material needs like food, water, and shelter but also symbolic and relational needs.

The goal of liberty is about protecting personal freedom. But personal freedom can lead to harm and so a major question for policymakers involves deciding when it is appropriate for the government to interfere with personal liberty in order to protect against harm. Generally it’s pretty clear that the American public supports interference if the harm is physical, but harms can also be economic, social, psychic, spiritual, or moral. Furthermore, harms might be cumulative–the harm might build up over a period of time.

The goal of security is about both objectively being safe and also subjectively feeling safe. Safety can include not only physical security, but also financial, cultural, social, and emotional security.

The goal of effectiveness involves the ability of the policy that is created to meaningfully address the problem it was designed to solve. Kraft and Furlong define effectiveness as, “the likelihood of achieving policy goals and objectives.”[4]

A final goal that we will consider is that of political feasibility. Political feasibility has to do with whether it is realistically possible to adopt a particular policy solution. Some proposed policies might be completely effective if enacted, but nearly impossible to pass given the current political environment. One common saying in politics is that the best is often the enemy of the good. What this means is that sometimes the policy solution that might be the most effective isn’t as good as a slightly less effective proposal that actually has enough political support to pass.

There are a few major things to keep in mind when it comes to goals like the seven I’ve outlined here. First, there are lots of different goals and different actors prioritize different goals. This simple principle is behind a lot of political conflict. Republicans tend to prioritize goals like liberty and efficiency while Democrats tend to prioritize equity and welfare. This means that when a given policy issue arises, each party will have a very different set of priorities in addressing it.

Second, even when different policy actors express support for a single goal, there are actually lots of ways of interpreting a goal. For example, does the goal of equity mean equity in terms of the outcomes for an individual or for members of a group?

Finally, it is important to recognize that many goals conflict with each other. Security and liberty, for example, are often in conflict. Consider, for example, debates about metal detectors and other security measures in schools. Added security protections go hand in hand with reductions in personal privacy (liberty). Even though an actor might view both as important goals, a policy that enhances security often does so to the detriment of individual liberty.

Policymakers are motivated by these values, which shape their approach to policymaking and the language they use to discuss policy. Advocates use these values to craft arguments for and against policies. One of the most useful skills you can develop as an observer of the policymaking process is to determine which values a given actor is prioritizing in a policy debate and to use that information to help understand the dynamics of the debate.

Who is to blame for problems?

A second factor influencing policy design involves a determination of blame. When something goes wrong, we naturally seek out its cause in order to hold that person or thing responsible for the problem. This is an important preliminary step in policymaking because a proposed solution is unlikely to be effective if it does not address the true cause of a problem. In practice, a lot of policy simply addresses effects rather than causes, but even in those situations, you’ll notice that the actors are still concerned about identifying the cause of the problem. It is also true that, as Kingdon’s Streams Model argues, policy solutions often exist before the problems even happen. But even in this case, policy actors still have to justify their policy proposal as something that is able to alleviate a problem, which involves a determination of blame.

These causal stories help us interpret the things happening around us, but they also point out who (or what) is to blame for the problem and, through this blame, affect the direction policy should take. Deborah Stone argues that there is a pattern to the types of stories we tell about the causes of problems.

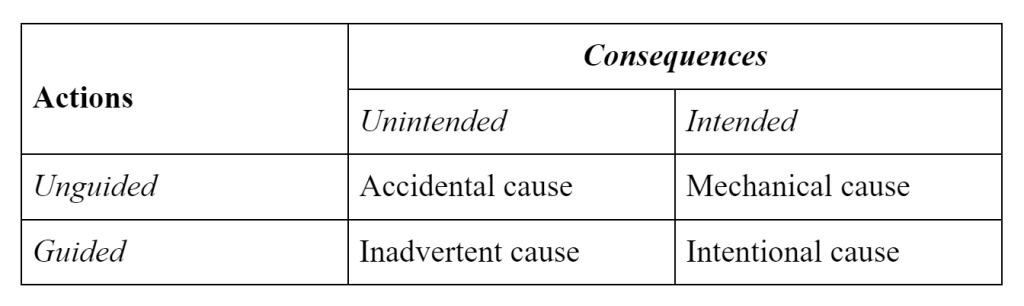

Stone argues that problems can be grouped according to two dimensions: actions and consequences. In terms of actions, problems might be guided or unguided. In terms of consequences, problems might be intended or unintended. This leads to four different types of causal stories that are used to explain problems, cast blame, and point to potential solutions. When something happens in the world, one of the first things that happens in response is an effort to explain why it happened. Stone shows us how these explanations tend to fall into one of four categories: accidental causes, mechanical causes, inadvertent causes, intentional causes.

Figure 5.2: Causal Stories

The first of these categories is what Stone calls accidental causes. These are situations where no one is clearly to blame for the outcome. Natural disasters fall into this category as do freak accidents. Any time we describe a situation as an “act of God,” we’re attributing the problem to an accidental cause, something beyond the scope of what any individual or institution could have prevented. Stone points out that “politically, this is a good place to retreat if you are being blamed, because in the realm of fate, no one can be held responsible.”[5]

The second category, mechanical causes, is how we define problems that are unguided but have indirectly intentional consequences. Machines or bureaucratic processes that are designed and trained by humans (guided) might function well most of the time, but occasionally lead to harm when the machines or bureaucrats fail to respond to changes in the environment or when they break down.

The third category, inadvertent causes, includes problems that are driven by purposeful human action but with unintended consequences. Stone calls one variation of this the “help-is-harmful” argument, which she says is particularly common among conservatives. Inadvertent causes can also include instances of ignorance and of carelessness.

The final group of causal stories include situations where there is a clear person or group responsible for an outcome and that person or group meant for the outcome to happen. Stone calls these intentional causes and argues that this “is the most powerful offensive position to take, because it lays the blame directly at someone’s feet, and because it casts someone as willfully or knowingly causing harm.”[6]

Keep in mind that the causal story that develops for a problem is not inherent, but rather it represents intentional efforts by political actors to make sense of the world around them. Causal stories are debatable and they can change over time. One actor might have an interest in pushing a narrative that attributes a problem to one type of cause while another actor is pushing a conflicting narrative. Or as new information emerges, we might shift from one causal story to another to make sense of a situation.

Causal stories lead directly to policy design because they create a framework that makes some policy approaches seem like a more effective option than others. In more formal terms, different causal stories lead to the use of different policy tools.

How do policymakers gain compliance?

Policy tools are the mechanisms that policymakers use to motivate people or institutions to behave in ways that satisfy the goals of public policy. As I demonstrated in the example about getting notes from a classmate, there are lots of different ways to gain the compliance of a particular group, or target population.

Policy tools can confer either benefits or burdens on the target population. Benefits or burdens might be financial, social, physical, mental, or emotional. Policy tools can also be either coercive or voluntary for the target population. In other words, the policy tool can incentivize, but not require participation or it can mandate participation.

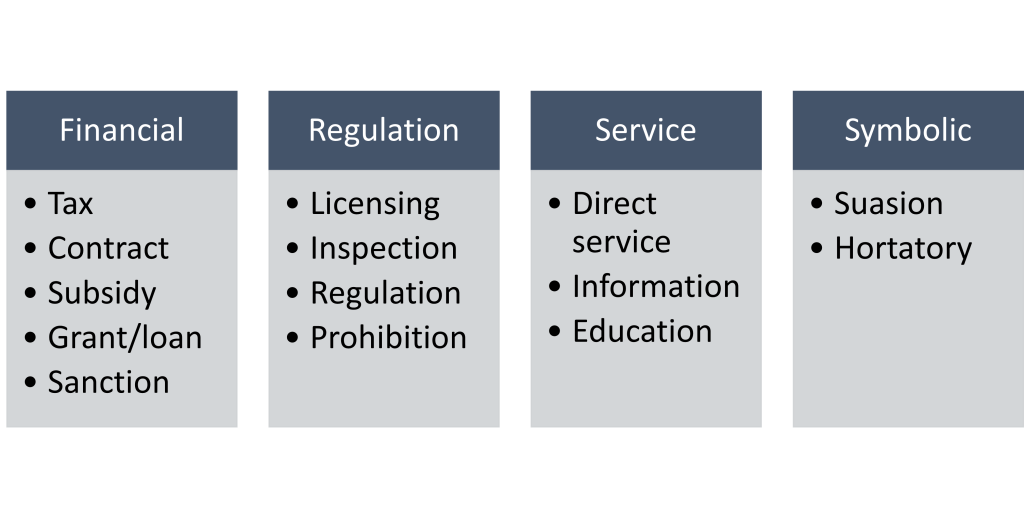

There is no definitive list of policy tools, or approaches that governments take to gain compliance, but I think it is helpful to think of four main categories of tools: financial, regulation, service, and symbolic.

Figure 5.3: Policy Tools

Financial tools include any type of policy that involves providing financial benefits in exchange for desired behavior. It also includes imposing financial penalties either to pay for government activities or as a penalty for undesired actions. Financial tools include taxes, contracts, subsidies, grants, loans, sanctions, and fines.

Regulation tools cover a broad range of activities from those that create procedures and standards to those that require punishment. Regulations requiring licensing or inspection often apply to businesses and may grant, require, or prohibit action. Regulations involving activity defined as criminal may include punishment that ranges from fines to imprisonment and even to death.

Service tools include policies that provide direct services, information, or education. Any government work that is done by the government itself to provide a good or service is an example of a service tool.

Finally, symbolic tools include policies that urge, but don’t require, compliance. Policy tools might attempt to persuade compliance with goals (called suasion). Policy tools might motivate good behavior through recognition and honor (called hortatory).

With all these options for policy tools, how do policymakers choose between them and is there a pattern to their choices?

Why does the policy look like this?

Anne Schneider and Helen Ingram argue that policy design, or the particular policy tools selected to address a problem, isn’t random or accidental. Instead, there is a pattern to the way policies are designed and that pattern directly relates to who the policy affects. Their theory, the Social Construction of Target Populations, offers both an explanation and a critique of this process. The theory rests on two important concepts: social constructions and target populations

Before we jump into this theory, I need to issue a warning. We’re going to be talking about stereotypes of groups, a widely held but simplified belief about a group of people. Some stereotypes are positive (Gustavus students are hard working!), but others are negative and can be very hurtful. Stereotypes might be based on a kernel of truth, but they can also be way off base. Most of us prefer to think that we aren’t susceptible to stereotypes…that we prefer to judge people individually rather than lumping them together as part of a group. But regardless of what we like to think about ourselves, it’s just a fact that humans tend to rely upon stereotypes. It is what motivates an entire set of biases and behaviors that we might not even be aware of, what psychologists call implicit biases. Digging into the psychology of implicit biases is more than we can accomplish in this book, but for now, it’s important to recognize that–like it or not–these biases and stereotypes exist and they impact human behavior.[7] Please hear me clearly when I say that talking about stereotypes (which we will be doing shortly) does not mean that we believe those stereotypes are true or accurate reflections of the group. It also does not mean that we condone the stereotypes. Pretending that people don’t hold these stereotypes doesn’t make them go away, but talking about them can make us more aware of how they function in society and how we might go about changing or even ending them.

I believe that change is possible because the stereotypes themselves are not inherently true statements about a group of people. They are socially constructed. That means that society has created a story about the group that includes information about the group’s habits, likes, dislikes, tendencies, morals, characteristics, goals, and motivations. This process of social construction happens through the media, art, public leaders, and personal experiences. It involves identifying a set of common attributes for an entire group of people and then attributing those attributes to individuals who are part of that group.

In the study of public policy, we can talk about that group as a target population. A target population is the group of people whose behavior you wish to change. This can be a tricky concept because almost every policy affects a broad range of people, both intended and unintended. When using this theory to analyze policy, it’s important to think about the primary intended target population, which is usually specified through the eligibility criteria of policy.

The attributes (or stereotypes) we hold for different target populations are normative. In other words, some of those stereotypes are positive and others are negative. Think about an attribute like “hard working”. Most of us would agree that hard working is a positive characteristic. We could probably think of individuals who we would describe as hard working, but I’d bet you can also think of groups you would describe as hard working (college students?). In contrast, an attribute like “lazy” connotes a negative image. Again, you could easily think of an individual person you could describe as lazy, but I’m guessing you could also come up with a group that you’ve heard described as lazy. Remember that it’s not important that you personally hold the belief that the group fits the attribute, but that you know there are a substantial number of people out there in the world who believe that. How would you know if such a belief exists? It’s likely you’ve seen that belief expressed by political leaders, on mass media, or in popular media (music, movies, etc.).

These positive and negative social constructions relate to beliefs about deservedness. Groups that are characterized by positive attributes are often deemed deserving of good things and undeserving of bad things while groups characterized by negative attributes are often viewed as undeserving of good things but deserving of bad things.

Because social constructions are constructed and not inherent, they can change. They can change either through actions that members of the group itself takes to change the perception others hold about it or through non-group members changing their beliefs. This type of external-led change usually happens when non-group members have personal experiences with members of the group that don’t conform to their expectations. As an example, consider a socially conservative person who has always held negative stereotypes about the GLBTQ community but then finds out that a close family member is gay. That personal experience will challenge the stereotypes they hold about the group. When that type of experience happens to enough people, that larger narrative about the group that supports the stereotype starts to break down. Just as media portrayals of groups can create a social construction, they can also help to change a social construction. Major, dramatic events can also lead to a change in social construction.

The other effect of the “constructed” nature of social constructions is that they are often contested. The group may be viewed with one set of attributions by one segment of society and a very different set of attributions by another segment. For our purposes, the biggest place we see this play out is between liberals and conservatives. As an example, think about the ways in which undocumented immigrants are viewed by liberals and by conservatives. Liberals emphasize a certain set of (mostly positive) attributes while conservatives emphasize a very different set of (mostly negative) attributes. Part of what is happening in the political world is a battle between these two competing narratives of the group.

Before we move on, I also want to point out the obvious fact that individual people are part of multiple groups and, thus, are subject to multiple social constructions. As we work with this theory, it’s helpful to remember that it is useful in explaining how policy impacts groups of people, but it won’t necessarily explain the outcome for a particular individual because individuals are part of so many different groups.

Before we jump into the meat of the theory, I want to pause to explain its significance. Most of political science is concerned with power as an explanatory variable. They measure power by things like wealth, participation in government, access to decision makers, and ability to organize effectively. Schneider and Ingram think that power matters, but they also draw our attention to the ways in which groups are socially constructed–the social construction of target populations–as a critical variable in explaining policymaking.

The Social Construction of Target Populations argues that we can understand the design of public policy by considering the interaction between political power and social construction. Schneider and Ingram present a typology based on these two factors that helps predict and explain the design of public policy.

One dimension of the typology is political power. Political power includes things like access to financial resources, civic participation, access to power, and the ability to organize. Some groups have strong political power while others have weak political power.

The second dimension of the typology is social construction. Social construction can be positive or negative. Groups with positive social constructions are described by positive attributes and are viewed as deserving of good things and undeserving of bad things. Groups with negative social constructions are described by negative attributes and are viewed as deserving of bad things and undeserving of good things.

The interaction of these two factors, power and social construction, results in four categories. Identifying the category in which a given target population fits is the first step in using the theory to predict or explain the selection of policy tools.

Figure 5.4: Social Construction of Target Populations

A target population that has a high level of political power and a positive social construction is likely to receive benefits from public policy and unlikely to experience burdens. Schneider and Ingram call target populations that meet this description as Advantaged. Advantaged groups have benefits that are oversubscribed, in other words, they get more benefits than they should, and burdens being undersubscribed, or getting fewer burdens than they should. Because advantaged groups have a lot of political power, they tend to have a lot of control over the policymaking process, which allows them to craft policies that maximize benefits and minimize burdens. Policies that have an advantaged target population are likely to use policy tools that provide resources (grants, subsidies, direct services) with few strings attached. When there are burdens, policy tools usually rely on voluntary or non-coercive tools like allowing the group to regulate itself. To relate back to Lowi’s typology from chapter 1, Advantaged groups are most likely to be the beneficiaries of distributive policy.

A target population that has low levels of political power but a positive social construction is likely to receive some benefits, but less than might be expected given how society views the group (benefits are undersubscribed). They are also likely to receive more burdens than expected (burdens are oversubscribed). Schneider and Ingram call this group Dependents. Dependents have little control over the political process. Think, for example, of children who are not able to vote and who don’t have an independent source of income or the ability to mobilize effectively. Children have little say in policymaking and so even though we view them favorably, policy concerning children is often less aggressive than we might expect. Policy tools for dependents often involve symbolic tools, the provision of information rather than direct services. Financial benefits like grants or subsidies might include eligibility requirements or other hurdles that make it difficult to apply for government help or create limitations on government help.

Contenders is the name Schneider and Ingram give to groups that have high levels of political power but a negative social construction. Benefits to Contenders tend to be given in secret or obscured while burdens are overt but generally only symbolic. One way benefits toward Contenders are hidden is by placing them within the tax code, which makes it difficult for the average citizen to notice or comprehend. Symbolic burdens include fines that might seem like a large amount, but represent only a small share of a company’s annual profit. Because of their access to political power, Contenders have some control over the policymaking process which helps them limit the impact of burdens and maximize their benefits. However, because of their negative social construction, political actors have to be careful about being too overt in distributing benefits to groups that fall in the Contenders category. Policy tools commonly used for Contenders include sanctions (a burden) and tax breaks (a benefit, but hidden in the tax code) or government contracts (a benefit that is not highly visible).

The final group are Deviants who suffer from both a low level of political power and a negative social construction. Deviants have virtually no control over policymaking because they don’t have access to political decision makers and decision makers have little to gain in terms of popularity by helping them. Deviants are unlikely to receive benefits from policy but they are very likely to receive burdens. Policy tools tend to be coercive and might include sanctions, imprisonment, or even death. Consider criminal penalties for drug possession, which tend to criminalize drug use rather than treating it as a medical condition (addiction).

The theory helps us to understand why particular policy tools are selected based on the political power that a target population holds and their social construction. However, the theory doesn’t end there and there is one additional contribution from the theory that I think is particularly important to mention. Not only do the social constructions of a group impact the type of policy tools used to change the behavior of the group, but the selection of those particular policy tools communicates a message to the group. Schneider and Ingram consider this feedback to be particularly important because the way a policy is designed sends a message to the groups about their status in society and what they should expect from the government. Individual citizens, particularly those who are part of the group itself, citizens internalize that message and the message affects how they view government and how they participate in government.

Members of Advantaged groups receive benefits from the government and those benefits communicate to members of those groups that they are important, valuable, and worthy of government attention. Advantaged group members receive the message that their opinions matter and that they should participate in the political process. They hear that the government works for them (and works well for them) and that the government cares about them. People who aren’t members of Advantaged groups see the benefits conferred on the Advantaged and it reinforces their status and positive social construction as deserving recipients of government benefits.

In contrast, Deviants receive mostly burdens from government and those burdens communicate the message that they are a detriment to society and undeserving of help. Deviants hear the message that the government doesn’t care what they think and doesn’t want their input into decisions. Out-group members see the burdens Deviants face and it confirms their beliefs that members of Deviant groups deserve the burdens they face and deserve to be disenfranchised from the political system.

Dependents hear the message that the government cares, but it might sound patronizing or condescending. Dependents hear that they are reliant on the good will of other people but they aren’t encouraged to find their own sense of agency. Paternalistic policies toward Dependents communicate to out-group members that Dependents should be protected and appeased but not empowered.

Contenders hear the message that they are powerful and important but that they’ll need to conceal their power in order to preserve their access. They hear that if they continue to financially support the political system, they will continue to receive oversubscribed benefits from that system. Out-group members see the benefits received by Contenders and superficial penalties they face as evidence that the system is biased and that money matters more than anything else.

All of this means that each of us experiences the world of policy and politics very differently depending on the messages we have received as members of socially constructed target populations. It also means that when analyzing policy, we need to think about what the policy tools say about and to the people who are most directly impacted by the policy.

On one hand, this is a fairly pessimistic place to end this discussion because the theory confirms what a lot of people already believe about politics: that strong, popular groups really do get more from the government while weak, unpopular groups bear more burdens. But I think the theory also gives us the tools for achieving change. If we understand that both power and social construction matter, we can use that information to focus our efforts on changing a group’s level of political power or its social construction, or both.

Changing political power involves mobilizing members of the group to vote, to contact policymakers, and to attempt to shape the public discussion over the issue. Changing social construction involves changing commonly-held beliefs about a group. Both of these efforts can involve media strategies like writing opinion-based articles for newspapers and magazines, so let’s spend a bit of time discussing this genre.

What is an op-ed?

Most of the content space of public affairs-oriented newspapers is taken up by news articles, articles written by journalists to report information about things that happened in the world. The journalists who write these articles are guided by a set of journalistic norms that encourage them to try to keep their reporting as neutral and fact-based as possible, focusing on answering basic questions about recent events in a way that is accurate and accessible to the general public. These news stories are not based on opinion, though they may report on the opinions of some political actors, and you might notice that they usually include information that comes from “both sides” of a given topic or debate.

Most public affairs-oriented newspapers also contain a smaller, separate section that is dedicated to arguments about the news stories covered by the paper. This section is often called the opinion section. This section of the newspaper usually features at least four different types of things: editorials, op-eds, letters to the editor, and editorial cartoons.

Editorials are brief articles written by newspaper-employed editorial staff about major issues. The people who write these editorials are not the same journalists who are writing the news articles; they are people specifically hired to write argument-based commentary about the topics covered in news articles. The editor or group of editors who write a newspaper’s editorials are not expected to remain neutral on a topic but rather to write something thoughtful and provocative that makes a clear argument. Newspapers tend to have editorial sections that lean either to the right or the left, which is where the perception that a newspaper is either liberal or conservative comes from. For example, the editorial board of the New York Times generally publishes editorials that make a more liberal argument (although there are conservatives on the editorial board) while the editorial board of the Wall Street Journal generally publishes editorials that make a more conservative argument. However, it is important to remember that–especially in a large newspaper–the editorial staff is generally separated from the news staff. In a small town newspaper, the person who writes news stories might be the same one who writes editorials, but they generally try hard to keep the news articles fact-based and neutral, saving their arguments for the editorial column.

Beginning in the 1970s, the New York Times added another set of opinion articles to present an alternative perspective to the ones articulated in the editorials. Because these articles were placed opposite from the editorial, they came to be called op-eds (opposite the editorial). Many op-eds (or sometimes just called “opinion” pieces) are written by columnists employed by the newspaper to produce a regular flow of articles each week. Other op-eds are written by people who don’t work for the newspaper but have expertise in a particular topic. Like editorials, op-eds are argument-driven essays that are meant to be thought-provoking and persuasive.

I’ll explain more detail about op-eds in just a bit, but for now, let me finish up describing the other things you’re likely to see in a newspaper’s opinion section.

Letters to the editor are letters written by readers of the newspaper in response to news articles or opinion pieces (editorials or op-eds). Letters are generally very brief and focus on one single and specific article that was published within the past week. Most newspapers limit letters to 200 words or less (The New York Times limits letters to 175 words). Newspapers usually require that the letter writer identify themselves and don’t print anonymous letters. Like editorials and op-eds, letters must be argument driven.

The final thing that is common in opinion sections is editorial cartoons, also known as a political cartoon. These are drawings, like you would find on the comics page, but they contain political commentary that relates to current events and/or politics. These are basically arguments like what you would find in editorials or op-eds made mostly with pictures (and a few captions) rather than words.

Now that we’ve talked about the opinion section of a newspaper, let’s focus a bit more on op-eds. As a reminder, the purpose of an Op-Ed is to make and support a persuasive argument about a relevant topic rather than to present both sides of an issue. As New York Times columnist Bret Stephens says, “op-ed pages are for one-handed writers.”[8]

Topics that are in the news usually make the cut as relevant, but it is also possible to make a case for a topic that isn’t in the news to be relevant if the argument you’re making is that the topic should be in the news. Remember that venue matters for relevance too…a story about an issue facing a specific state wouldn’t be relevant to a national audience, but it would be relevant to a state audience.

Speaking of audience, the audience for an Op-Ed are general readers of the particular news outlet (i.e. The Star Tribune, USA Today, The New York Times, The Mankato Free Press, The Gustavian Weekly, etc.). Now that everything’s available through a quick Google search, it is true that anyone anywhere in the world can search for and read an op-ed online. However, the people who write op-eds still focus on the readers of the newspapers as their primary audience. They know that most readers are reasonably informed about issues, but they aren’t experts. This means that op-ed writers try to avoid technical jargon.

One thing that op-ed writers know is that politicians and decision makers (and their staff) are regular readers of newspapers and op-ed pages and so op-ed writers are often writing with those decision makers in mind as they build their argument.

In terms of style and writing conventions, op-eds tend to be organized and written in a very particular way. Op-eds open with a lede, or a sentence that is designed to grab the reader’s attention. A lede should make the case to the reader that the topic is interesting, important, and timely. There are lots of approaches you can use to develop a good lede. Connecting the topic of the op-ed to a current event is a very common technique. A related technique is to use an anniversary of an event as the lede. Both of these techniques communicate a sense of timeliness. Another approach is to use a dramatic anecdote or personal story. This works best if you have an experience or expertise that relates to the topic of the op-ed

Within the first few paragraphs, the op-ed should articulate an argument. You might remember that an argument (sometimes called a thesis) is a statement about which reasonable people can disagree. If your “argument” is something that is simply true or that everyone already agrees with, it is not a good argument to make. It can feel a little risky to articulate an argument when you know there are people who might disagree, but this is exactly what you should be doing in order to have an interesting and effective op-ed. Because coming up with an argument that you know might be controversial is a little intimidating, some writers have the instinct to work their way up to the argument, not fully articulating it until the very end. If this is you, I need to tell you that op-ed writing is not like writing a mystery novel…your reader wants to know who killed Colonel Mustard with the candlestick in the billiards room at the beginning of the piece, not at the end.

The op-ed should then develop and support that argument through a series of supporting points. You should have at least two supporting points and I wouldn’t recommend having more than four supporting points. An op-ed just isn’t long enough to develop your argument if you have too many supporting points. The length limitations for different news outlets vary, but most have a limit of 700-800 words. For reference, that’s about three double-spaced pages, which is not a lot of room to work with. For each supporting point, the writer should present credible evidence and explain how the evidence supports the individual point and the larger argument. Writers should think carefully about what kind of evidence will be most effective in supporting their argument.

There are many types of evidence that writers use. A writer might incorporate statistical evidence, like the number of people impacted by an event or the percentage of people who engaged in a particular activity. Research findings are another, closely related, form of evidence. Research findings make causal claims based on research that shows that two or more factors are related. Writers might rely on the testimony of experts or the first-hand experience from people who are impacted by an issue. Writers might even incorporate their own personal experiences as a form of evidence. Historical facts and figures might make up a form of evidence. And often, writers will use logical reasoning or an analogy to support their argument. A good op-ed writer is going to incorporate multiple forms of evidence in building their argument rather than relying on just one form of evidence.

Citing evidence is important in an op-ed, but it looks very different from how we cite evidence in a traditional research paper. When an author submits an op-ed, they have to demonstrate to their editor that they have evidence to support their claims. This might mean providing a bibliography of sources. However, a published version of an op-ed won’t include a bibliography and it won’t look like a traditional research paper.

Rather than using footnotes or in-text citations, citations are embedded into the text. Embedding a citation means to include relevant details about the source of the information right in the text itself. It takes some practice to learn what the relevant details are for a particular source of evidence. It might mean providing information about the author, about the publication title, or about the author’s institutional affiliation. Very rarely will it mean including the title of the source in the text because titles don’t do much in terms of establishing credibility. The key is to think about what information the reader needs to know in order to find the evidence credible. In essence, as a writer of an op-ed, you are trying to cash in on the source’s credibility to strengthen your own credibility.

As you read more op-eds, you’ll begin to notice how authors use strong signal verbs to introduce sources. Sources might “argue”, “emphasize”, “endorse”, “contend”, or “urge.” Researchers at certain prestigious universities might “claim”, “reaffirm”, or “question.” Analogies might “demonstrate”, “suggest”, or “warn”. Using specific and vivid verbs when presenting supporting evidence helps the author to gain the credibility that comes from the source while keeping their reader engaged.

After developing 2-3 supporting points, an op-ed writer needs to clearly address the counterargument to their position. This is the time to raise and respond to the argument that a reader might make in response to the op-ed. It’s tempting to throw out a very weak argument, a technique that is called making a straw-man argument, but this is actually a very bad strategy. Your argument is only as strong as your ability to respond to a strong counterargument. If there is a strong counterargument and you don’t raise and respond to it, your reader will know that and assume it’s because your argument isn’t strong enough. If there isn’t a strong counterargument to your position, it is probably a sign that you aren’t really making an argument (remember, an argument has to be arguable!). As with the supporting points you develop, you can’t just assert your response to the counterargument; you have to provide evidence in support of your assertion. Be sure to embed those citations when you are developing your response to the counterargument just like you did when you were developing your own supporting points.

A good op-ed usually wraps up by connecting back to the lede in some way and restating the argument. Since you are trying to get your reader to change their mind about an issue or take some action on an issue, this is the place to say that. Should Congress pass a bill? Say that. Is it time for the American people to email their legislators? Tell them to do it. Don’t spend this paragraph summarizing everything you’ve already said, but make sure you give your reader the main take-away point.

I’ve just described a lot. And remember, you have to do that all within about 700-800 words. Yikes! This means that editing is super important with an op-ed. A good op-ed writer will probably start with a piece that’s about twice as long as they need and then do some ruthless editing. One thing to pay attention to is passive voice. With passive voice, the subject of the sentence is acted upon by the verb (that sentence itself is written in passive voice!). Passive voice sentences usually contain a conjugated form of the verb “to be”. With active voice, the subject of the sentence performs the action. In policy writing, this also means that it is clear exactly who is responsible for doing the action. (i.e. The legislature passed the bill (active) vs. The bill was passed by the legislature (passive). The reason this matters for op-eds is because writing with active voice usually takes up fewer words and because it is usually more vibrant and interesting to read.

The final writing convention that I want to emphasize about op-eds is that they usually feature very short sentences and paragraphs. You might even find a one sentence paragraph in an op-ed! In a traditional research paper you might use paragraphs made up of 5-6 sentences. This would be very uncommon in an op-ed. Try keeping your sentences zippy and your paragraphs short.

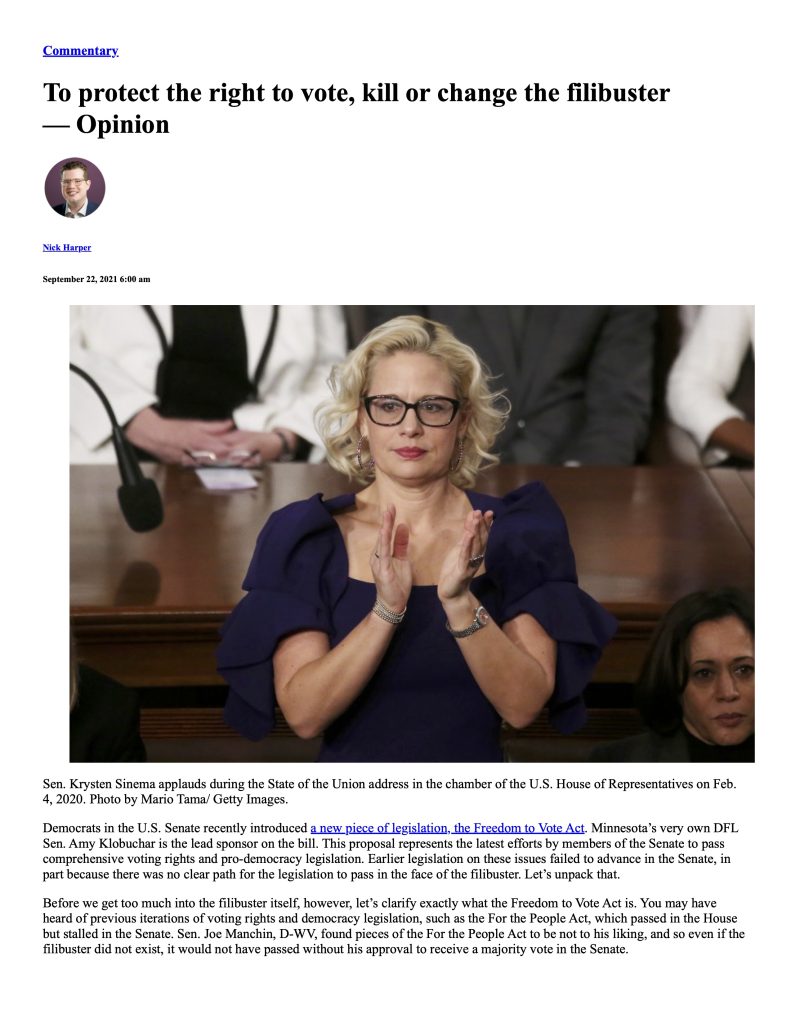

Take a look at this sample op-ed written by Nick Harper ‘10 and published in the Minnesota Reformer. Can you spot the stylistic markers that make it an op-ed? Who wrote it? What media outlets published it? What members of the public do you think they hope will read it? What purpose do they have for writing it?

Figure 5.5: Sample Op-Ed by Nick Harper ‘10, Senior Policy Attorney for the advocacy group State Voices (https://www.statevoices.org/). Source: Republished from The Minnesota Reformer under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Why do you write?

Figure 5.6: Mikka McCracken ‘09, Senior Manager at Autodesk

My name is Mikka McCracken. I was adopted from South Korea as an infant and grew up in a small town in northern Minnesota. I have lived in Chicago, Illinois since graduating in 2009. After failing my first three chemistry tests as a first-year, pre-med track Gustavus student, I took a J-term non-profit organizations class and found my way to a major in political science and minor in peace studies.

I began my career working with a national non-profit, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA). After starting in gender justice advocacy, I transitioned into leadership with ELCA World Hunger, the church’s global relief and development organization at work in over 60 countries. Finally, I designed and launched the organization’s first innovation function to help the church connect with and learn from the experience of GenZ people.

In late 2020, I pivoted from non-profit into for-profit and big tech. Now, I am a senior global program manager at Amazon.com, Inc. where I am the single-threaded leader of a global employee experience program for 450 people in 30-plus countries. So far, I have yet to go into a job that existed before I was in it. I love the challenge of closing the gap between a big, audacious vision and the real-time, practical experience of that idea in action. That’s where writing comes in.

When I began working at Amazon, one big surprise was the organization’s writing culture. Whether I’m proposing a project idea, preparing a weekly business update, or drawing together a new work team, the work begins with the formal process of “doc writing.” Good docs are a mix of descriptive/informative and influence writing. They clarify the issue at hand, create a level playing field for conversation, and speed up decision-making.

Every document includes an outline: purpose (i.e., Why is this document being written? What is this document about? Who is it for? How should it be used?); proposal (i.e., a proposed action, learning, idea); data (i.e., often a combination of internal and external research, including citations, and both quantitative and qualitative content); and a frequently asked questions (FAQ) section. We even include appendices – though all your main argument and content should be understandable from the body of the doc itself. In addition to doc writing, I also draft executive messages, scripts, and talking points for organization-wide communications and events, both for myself and executive leadership.

Here are my top four takeaways for writing at work:

- Know your point; get to it; provide the right information to help others understand. At Amazon, my ability to craft a solid thesis with supporting evidence, self-edit to remove filler words, and write in active tense actually make a difference in my performance. Being a strong writer makes me a better, more competitive team member.

- Remove your ego and ask for help. Every Amazon doc goes through a “doc review” where a small group reads your doc and gives live feedback. This process strengthens both my writing and – most importantly – my idea. Seeing my document through the eyes of others is key, so I ask colleagues for feedback.

- Pro tip: In addition to asking other subject matter experts, I also ask for feedback from someone who has very little knowledge of my topic area. The new reader often provides the best insights for clarity, because they cannot read between the lines.

- Start early. Most of my writing is for executive leadership consumption, which means shorter is better, and quality, focused products take more time. (Thomas Jefferson is thought to have said, “The most valuable of all talents is never using two words when one will do.”) Typically, my first drafts are too long and full of extra content. By the time I reach the doc review stage, I am on my fifth or sixth draft.

- Inclusion matters. Though English is the common business language in my organization, my colleagues are often working in their second, third, or fourth language. For clarity, I try to write with basic vocabulary and shortened sentence structure.

Even with all this writing, I don’t consider myself a strong writer. Recently, I went back to school and completed a master’s in Organizational Leadership and Learning at George Washington University. At first, it was a challenge to switch from business writing back into formal, academic writing. Now, I am stronger in both areas.

I never could have guessed how all the writing, research methods, and argument analysis from my liberal arts, political science degree would play out, but I use those skills almost every day. Program management, like all my previous roles, is all about influence and collaboration. I stick with the writing, because I care about the work. Happy writing!

What comes next?

In this chapter, we explored the process of policy design, looking for patterns to help us understand why policies look the way they do. We learned that policies don’t just pop out looking a certain way. They are shaped by the goals policymakers hold, the causal stories they tell about the problem, and the social construction and political power of target populations. The shape of public policy is a result of strategic decisions made by political actors. Furthermore, the design of policies communicates important information to the public about their worth and place in society.

With this in mind, we can turn to the final big question addressed by this book and that is how do we know if the policies work. The final substantive chapter addresses the topic of policy evaluation.

Questions for discussion:

- Are there some goals that are more (or less) important to you? Why do you think these goals have come to be a priority for you? Are there ways in which some of your goals might conflict with each other?

- Consider a current policy debate. What goals are at stake in this debate? Do people with different views on the topic seem to be prioritizing different goals (or do they interpret the same goal in different ways)?

- Thinking about some of the situations that are in the news right now, can you identify the causal stories that are being created to explain those situations? How might the dominant causal story impact the policy response?

- What are some common attributes used to describe groups of people in policy debates? Which are positive and which are negative? To what groups are these attributes applied? How do you think these particular attributes came to be applied to these groups?

- Pick a policy you care about. Who is the target population for that policy? How would you characterize that target population in terms of its political power and social construction? Are the policy tools used in the policy the ones that the Social Construction Theory of Target Populations predicts?

- Why do you think that politicians and decision makers read op-eds? Are there reasons to think this might help the policymaking process? Are there reasons to think it might be harmful to the policymaking process?

- What questions does the material in this chapter raise for you about policy design or writing about public policy?

Glossary

Accidental Causes: A type of causal story in which no one is clearly to blame for the outcome of a situation.

Active Voice: The subject of the sentence performs the action.

Advantaged: A target population that has a high level of political power and a positive social construction. Advantaged groups are likely to receive benefits from public policy and unlikely to experience burdens.

Causal Stories: Help interpret the things happening around us, but they also point out who (or what) is to blame for the problem and, through this blame, affect the direction policy should take.

Contenders: A target population that has a high level of political power but a negative social construction. Contender groups are likely to receive hidden benefits from public policy and visible, but minimal burdens.

Counterargument: A response to a writer’s argument. Good argumentative writing always raises and responds to a strong counterargument.

Dependents: A target population that has low levels of political power but a positive social construction. Dependent groups are likely to receive some benefits, but less than might be expected given how society views the group.

Deviants: A target population that has a low level of political power and a negative social construction. Deviant groups are likely to receive few benefits and lots of burdens by public policy.

Editorials: Brief argument-driven essays written by newspaper-employed editorial staff about major issues.

Editorial Cartoons (also known as Political Cartoons): Drawings containing political commentary that relates to current events and/or politics.

Effectiveness: Involves the ability of the policy that is created to meaningfully address the problem it was designed to solve.

Efficiency: Getting the most for the least, or achieving an objective for the lowest cost.

Embedding a Citation: Including relevant details about the source of the information right in the text itself instead of using a footnote or a parenthetical citation.

Equity: Fairness or justice in the distribution of the policy’s costs, benefits, and risks, across population subgroups.

Financial Tools: Any type of policy that involves providing financial benefits in exchange for desired behavior.

Implicit Biases: An entire set of biases and behaviors toward a group of people of which we might not even be aware.

Inadvertent Causes: A type of causal story in which problems are driven by purposeful human action but with unintended consequences.

Intentional Causes: A type of causal story in which there is a clear person or group responsible for an outcome and that person or group meant for the outcome to happen.

Letters to the Editor: Letters written by readers of the newspaper in response to news articles or opinion pieces (editorials or op-eds).

Lede: A sentence at the very beginning of an article that is meant to grab the readers’ attention.

Liberty: Protection of personal freedom.

Mechanical Causes: A type of causal story in which problems are unguided but have indirectly intentional consequences.

News Articles: Articles written by journalists to report information about things that happened in the world.

Normative: A description or claim about how the world ought to be based on value judgements.

Oversubscribed: When you get more of something than you should.

Passive Voice: The subject of the sentence is acted upon by the verb.

Political Feasibility: Has to do with whether it is realistically possible to adopt a particular policy solution.

Policy Tools: The mechanisms that policymakers use to motivate people or institutions to behave in ways that satisfy the goals of public policy.

Regulation Tools: Cover a broad range of activities from those that create procedures and standards to those that require punishment.

Security: Refers to both objectively being safe and also subjectively feeling safe.

Service Tools: Policies that provide direct services, information, or education.

Social Construction: The process of ascribing meaning to an event or group. A socially constructed story about the group that includes information about the group’s habits, likes, dislikes, tendencies, morals, characteristics, goals, and motivations.

Stereotypes: Involves identifying a set of common attributes for an entire group of people and then attributing those attributes to individuals who are part of that group.

Symbolic Tools: Policies that urge, but don’t require, compliance.

Target Population: The group of people whose behavior you wish to change.

Types of Evidence: There are multiple forms of evidence used in building arguments including: statistical evidence, research findings, testimony of experts, or even personal experience of writers.

Undersubscribed: When you get less of something than you should.

Welfare: The general belief that society should help individuals and families when they are in dire need.

Additional Resources

Implicit Association Test at Harvard University: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/education.html

The Op-Ed Project: https://www.theopedproject.org/

- Michael E. Kraft and Scott R. Furlong, Public Policy: Politics, Analysis, and Alternatives 7th Edition (California: CQ Press, 2021), 170. (Italics added) ↵

- Deborah Stone, Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, 3rd Edition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012), 63. (Italics added) ↵

- Deborah Stone, Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, 3rd Edition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012), 85. (Italics added). ↵

- Michael E. Kraft and Scott R. Furlong, Public Policy: Politics, Analysis, and Alternatives 7th Edition (California: CQ Press, 2021), 170. ↵

- Deborah Stone, Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, 3rd Edition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012), 209. ↵

- Deborah Stone, Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, 3rd Edition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012), 209. ↵

- You can learn more about implicit bias and even take online tests to identify your own implicit biases about different groups through the Project Implicit group at Harvard University: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/education.html ↵

- Bret Stephens, “Tips for Aspiring Op-Ed Writers,” The New York Times , August 25, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/25/opinion/tips-for-aspiring-op-ed-writers.html ↵

Fairness or justice in the distribution of the policy’s costs, benefits, and risks, across population subgroups.

Getting the most for the least, or achieving an objective for the lowest cost.

The general belief that society should help individuals and families when they are in dire need.

Protection of personal freedom.

Refers to both objectively being safe and also subjectively feeling safe.

Involves the ability of the policy that is created to meaningfully address the problem it was designed to solve.

Has to do with whether it is realistically possible to adopt a particular policy solution.

Help interpret the things happening around us, but they also point out who (or what) is to blame for the problem and, through this blame, affect the direction policy should take.

A type of causal story in which no one is clearly to blame for the outcome of a situation.

A type of causal story in which problems are unguided but have indirectly intentional consequences.

A type of causal story in which problems are driven by purposeful human action but with unintended consequences.

A type of causal story in which there is a clear person or group responsible for an outcome and that person or group meant for the outcome to happen.

The mechanisms that policymakers use to motivate people or institutions to behave in ways that satisfy the goals of public policy.

Any type of policy that involves providing financial benefits in exchange for desired behavior.

Cover a broad range of activities from those that create procedures and standards to those that require punishment.

Policies that provide direct services, information, or education.

Policies that urge, but don’t require, compliance.

Involves identifying a set of common attributes for an entire group of people and then attributing those attributes to individuals who are part of that group.

An entire set of biases and behaviors toward a group of people of which we might not even be aware.

The process of giving a problem its meaning and worth.

The group of people whose behavior you wish to change.

A description or claim about how the world ought to be based on value judgements.

Includes things like access to financial resources, civic participation, access to power, and the ability to organize.

A target population that has a high level of political power and a positive social construction. Advantaged groups are likely to receive benefits from public policy and unlikely to experience burdens.

When you get more of something than you should.

When you get less of something than you should.

A target population that has low levels of political power but a positive social construction. Dependent groups are likely to receive some benefits, but less than might be expected given how society views the group.

A target population that has a high level of political power but a negative social construction. Contender groups are likely to receive hidden benefits from public policy and visible, but minimal burdens.

A target population that has a low level of political power and a negative social construction. Deviant groups are likely to receive few benefits and lots of burdens by public policy.

Articles written by journalists to report information about things that happened in the world.

Brief argument-driven essays written by newspaper-employed editorial staff about major issues.

Letters written by readers of the newspaper in response to news articles or opinion pieces (editorials or op-eds).

Drawings containing political commentary that relates to current events and/or politics.

This term is related to news articles and references in the first sentences in an article that are meant to grab the readers’ attention; answers the big questions of who, what, where, when, why, and how; and details provided in an inverted pyramid style.

There are multiple forms of evidence used in building arguments including: statistical evidence, research findings, testimony of experts, or even personal experience of writers.

Including relevant details about the source of the information right in the text itself instead of using a footnote or a parenthetical citation.

A response to a writer’s argument. Good argumentative writing always raises and responds to a strong counterargument.

The subject of the sentence is acted upon by the verb.

The subject of the sentence performs the action.