8 Environmental Policy

Katherine Knutson and Eric Fowler

Wondering why some text is in blue? Click here for more information.

8.0 Environmental Policy

In 2015, a group of 21 young people (including future Gustavus student Nathan Baring ‘22[1]) filed a lawsuit against the U.S. federal government arguing the government was endangering their future by failing to take action against climate change despite knowing about its harmful effects. The case, Juliana v. United States, has been on a legal roller coaster ever since, with the federal government (both under Republican and Democratic administrations) working to have the case dismissed.[2]

Figure 8.1: Nathan Baring ‘22, one of the 21 plaintiffs in Juliana v. United States, stands in front of Old Main at Gustavus.

Juliana, and the debate over climate change, are one chapter in a larger story of environmental policymaking in the United States. Rinfret, Scheberle, and Pautz define environmental policy as “a broad umbrella term that encompasses government action, or inaction, related to the natural environment.”[3] Such policies cover a wide range of environmental media, or components of the natural environment, including air, water, land, and wildlife. Environmental policy is closely related to energy policy since energy production, distribution, and consumption have clear environmental impacts and given recent efforts to develop more renewable sources of energy in response to climate change.[4]

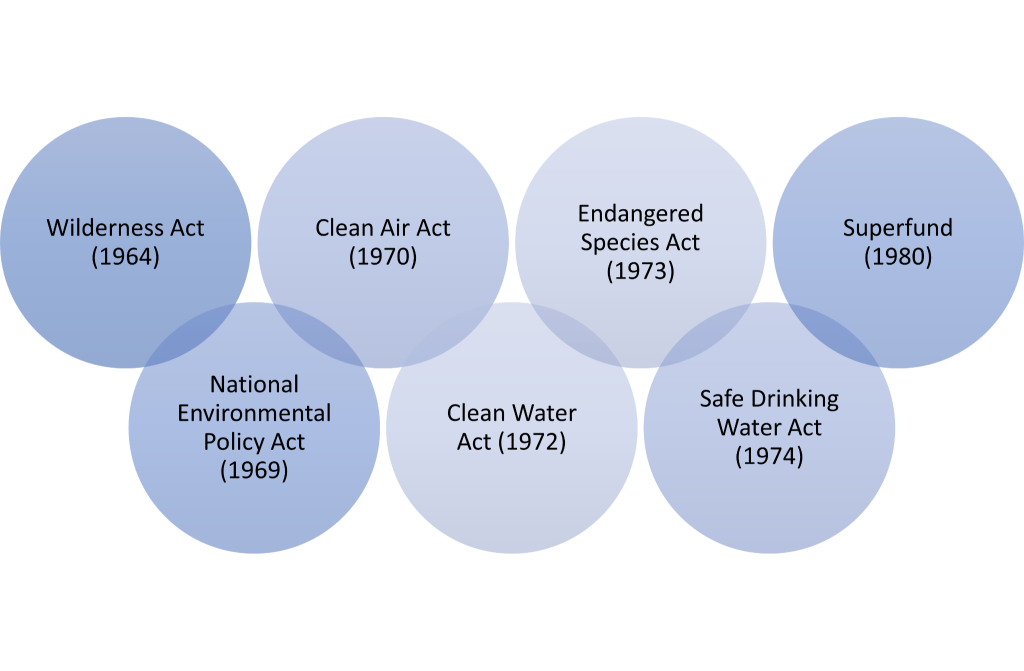

Environmental policymaking has gone through several phases. The first efforts related to protecting the environment began in the 1900s highlighting a philosophical debate between conservationists, who argued in favor of using natural resources wisely, and preservationists, who advocated for the complete protection of nature and wild areas.[5] It was during this phase when national parks and national forests were established (pleasing preservationists) and the Bureau of Reclamation was formed to help manage water use in western states (pleasing conservationists). It was also during this time period that many of the first environmentally-focused advocacy groups formed, including the Sierra Club (formed in 1892) and the National Wildlife Federation (formed in 1936).

Despite these initial efforts toward conservation and preservation, this was also a time of industrialization and population growth. The rise of factories contributed to significant air and water pollution, which led the federal government to pass the Air Pollution Control Act of 1955 and the Clean Air Act of 1963. Despite their names, these laws only required the federal government to study the causes of and solutions to air pollution, not to actually “control” or regulate pollution.[6]

Environmental problems are a classic example of a collective action problem. A collective action problem is a situation in which everyone would be better off if they worked together to achieve a goal, but their conflicting interests and personal self interest keep them from doing so.[7] One type of collective action problem is called the tragedy of the commons.[8] The tragedy of the commons is a situation in which people who have access to a common resource (such as water, air, or land) act in their own self-interest by using the resource, which negatively impacts access to, or the quality of, the resource for others. As industry grew, businesses benefited by dumping toxins directly into lakes and rivers, burying toxic waste, and using as much land as necessary to increase production, despite the obvious harms to air, water, and land quality. In cases such as this, government action is necessary. As Kraft and Vig argue, “government plays a preeminent role in this policy arena primarily because environmental threats, such as urban air pollution and climate change, pose risks to the public’s health and well-being that cannot be resolved satisfactorily through private actions alone.”[9]

8.1 Major environmental policies

The growing problem of pollution led to the modern age of environmental policymaking. Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act in 1969, which firmly established a role for the federal government in protecting the environment. The law was signed by President Richard Nixon as his first official act of the year on January 1, 1970. The NEPA asserted that it is the policy of the federal government, in partnership with the states, to “create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony.”[10] It also required federal agencies to conduct an environmental impact review for proposed federal actions. Furthermore, the law established the Council on Environmental Quality, housed within the Executive Office of the President, which was designed to help advise the president and congress on matters related to the environment and to ensure that federal agencies followed the requirements of NEPA.

Nixon followed the enactment of NEPA with an executive order establishing the Environmental Protection Agency for the purpose of protecting human health and the environment. Upon its creation, the EPA drew together multiple existing government agencies focused on environmental protection, energy, and public health.

These two actions–passage of NEPA and creation of the EPA–preceded a wave of policymaking focused on environmental protection.

Air

The Clean Air Act, first passed in 1963 to study air pollution, was significantly amended in 1970. The new CAA regulated air pollution within the U.S. and created federal air quality standards to protect human health and the environment. The CAA was amended multiple times, with particularly significant changes in 1977 and 1990 to further expand federal protection over air quality.[11] Part of the CAA requires the Administrator of the EPA to set emission standards for motor vehicles that contribute to harmful air pollution.

In 2003, the EPA’s administrator decided that the EPA did not have the authority to regulate carbon dioxide emissions or other greenhouse gasses linked to climate change. In response, twelve U.S. states and several cities sued the EPA to force the agency to regulate those emissions. The case, Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency (2007), eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court and, in a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the EPA must take action to regulate four greenhouse gasses emitted by new vehicles (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and hydrofluorocarbons) as part of their mandate from the Clean Air Act.[12]

Water

The Clean Water Act, passed in 1972, amended the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948. The CWA established a structure for regulating the discharge of pollution from point sources and set water quality standards for lakes, rivers, streams, wetlands, and reservoirs (so called surface water).[13] Point source pollution is pollution that comes from a single source that is easy to identify, like a factory. In contrast, non-point source pollution is harder to track and comes from multiple locations, like storm runoff. Amendments to the CWA in 1987 attempted to address non-point source pollution by directing states to develop plans to curb runoff from stormwater from farmland, construction sites, and urban areas and other non-point sources of water pollution.

In 1974, Congress passed the Safe Drinking Water Act to specifically protect access to safe drinking water. The law requires the EPA to set national standards for drinking water quality and works with states to monitor and track harmful contaminants in drinking water.[14]

Land

Several policies protect and conserve public land or regulate the use of public land. The 1964 Wilderness Act set aside over 9 million acres of land for federal protection. Today, there are over 109 million acres of federal land protected by the Wilderness Act, managed primarily by the National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[15] The Federal Land Policy and Management Act, passed in 1976, established guidelines for managing public lands.[16] Managing public land involves balancing the multiple uses of that land including historic preservation, scientific discovery, recreation, economic development, and energy production.[17]

A related set of policies address solid waste, hazardous waste, and waste clean up…in other words, what to do with all the stuff we produce but no longer want and the dangerous byproducts of the stuff we produce. The 1976 Resource Conservation and Recovery Act monitors the generation, transportation, storage, and disposal of hazardous waste through the EPA and it encouraged states to develop plans for solid waste disposal in landfills.[18] In 1980, Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response and Liability Act, more commonly known as Superfund. This federal pot of money helps to coordinate and fund hazardous waste cleanup efforts across the country. Originally, the money for this program came mostly from taxes imposed on petroleum and chemical producers, but today it comes directly through government spending. The EPA maintains a list of priority clean up sites, which as of January 2024 has 1,336 sites listed, including one in Mankato, MN.[19]

Wildlife

Some of the agencies overseeing wildlife protection were established in the first era of environmental action. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, for example, was created in 1939 through a merger of the Bureau of Biological Survey and the Bureau of Fisheries. The 1956 Fish and Wildlife Act took the initial steps of establishing a federal policy for conserving fish and other wildlife, and several subsequent bills attempted to protect endangered species, but the Endangered Species Act of 1973 was the most significant effort by the federal government to protect wildlife. The ESA requires the federal government (through the Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service (also known as NOAA Fisheries)) to determine whether species are endangered or threatened, give those species the protection of the federal government, and create recovery plans.[20] In addition to protecting animals, the ESA also protects endangered or threatened plants.

The flurry of environmental policymaking in the 1970s and 1980s slowed dramatically beginning in the 1990s, in large part due to political factors that I will discuss shortly. Despite growing consensus in the scientific community that human activity is the primary cause of climate change, the federal government has been unable to pass significant new legislation protecting the environment (again, more on this in just a bit).

Figure 8.2: Major Environmental Policies in the U.S.

Most recently, support for environmental initiatives has been tucked into larger spending packages. For example, the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, passed in response to the Great Recession, focused on stimulating job creation. But it also included over $90 billion in research, funding, and tax incentives for environmental initiatives related to developing clean energy.[21] A little over a decade later, President Joe Biden signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 (also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law), which devoted federal spending to public transit, environmental projects, electric vehicles, and the transition to renewable energy. The following year, Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act into law. The IRA was the largest investment by the U.S. federal government into climate-related policies in U.S. history. The law devoted $391 billion to reduce carbon emissions and explicitly defined carbon dioxide as an air pollutant under the Clean Air Act.[22] The law also created tax breaks for the production of low-carbon energy such as wind and solar and for individuals to purchase electric vehicles. Policy analysts predicted the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Act would together result in reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 40% below 2005 levels by 2030.[23] Upon taking office in January 2025, President Trump moved quickly to block some provisions of the IRA related to environmental protection by issuing a freeze on federal grants and cancelling funding for green energy projects.[24]

Major trends and themes

Several trends have emerged over the past three decades of environmental policymaking in the U.S. that are worth mentioning before we move on to address other questions about the policymaking process.

During the golden era of environmental policymaking in the 1970s, public opinion strongly supported government action and both parties worked to pass environmental legislation. Remember that NEPA and the EPA both occurred under Republican Richard Nixon. To be sure, conservatives during this time period tended to oppose policies that protect the environment at the expense of business while liberals tended to support such policies, much as they do today.

However, in contrast to ideological differences, party affiliation was not an important predictor of public opinion on the environment until the early 2000s. For example, in 1997, 46% of Democrats and 47% of Republicans reported believing that the effects of global warming had already begun to happen. By 2023, however, 85% of Democrats believed that but only 33% of Republicans did, a gap of 52%.[25] As Kraft and Vig point out, “since 1995…the bipartisan consensus on environmental policy has broken down, replaced by an increasingly acrimonious debate between the two major parties.”[26] Republican leaders in Congress and the executive branch have been among the most prominent skeptics of climate change and of the scientific evidence demonstrating human activity is the main cause of climate change.

As party differences began to emerge in the 1990s, it became more difficult for Congress to pass environmental legislation. Democrats controlled both the House and Senate from 1987-1994, but Republicans gained control of both chambers from 1995-2006, the same time Republican party leaders became less supportive of environmental policy and more skeptical of climate change. Republican opposition stems largely from their preference for reducing government regulations and protecting job and economic growth, all of which were viewed by Republicans as being in conflict with efforts to protect the environment. Between 2007 and 2024, there were multiple periods where Democrats controlled one chamber and Republicans controlled the other, making it nearly impossible for the two chambers to agree to identical policy language.

Due to the challenges within Congress, policymaking made three adaptations. First, federal policymaking shifted from legislation to regulation and executive action. In the absence of new legislation passed by Congress, agencies worked to clarify existing legislation and respond to emerging scientific research through creating new regulations. Presidents have also taken independent action, such as President Bill Clinton’s executive order requiring federal agencies to identify and address any negative health or environmental effects of federal policy that disproportionately harm minority or low-income populations.[27]

Second, with the federal government largely deadlocked on new policy, the states moved into action. States already played a major role in enforcing federal environmental policies, but states took new action to extend environmental protections beyond federal guidelines. As Rabe notes, states “have also made increasingly aggressive use of litigation to attempt to force the federal government to take new steps or reconsider previous ones.”[28]

In Minnesota, for example, Democrats passed Clean Energy by 2040 in 2023. The policy requires all electric utilities to get a percentage of their electricity from carbon-free sources. The percentage grows from 80% in 2030 up to 100% by 2040.

Finally, with the relative absence of U.S. federal leadership in addressing climate change, international organizations have taken a leading role. The United Nations formed the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which prepares scientific reports on climate change and efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change. Countries met in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan to negotiate a plan for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Though the United States signed the Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change, it was never ratified by the Senate. World leaders negotiated another international treaty in 2015. The Paris Climate Agreement set the goal of reducing the increase in global average temperature, with individual countries determining their own steps to reach their emissions reductions commitments.[29] The U.S. signed the Paris Agreement in 2016, but President Donald Trump announced his intention to withdraw the U.S. from the agreement in 2017. When President Joe Biden assumed office, one of his first official acts was rejoining the Paris Agreement.[30] Trump immediately withdrew from the Paris Agreement upon taking office in January 2025.

8.2 Who are the players?

As we’ve already seen, environmental policy involves a range of local, state, federal, and international government actors in addition to unofficial actors such as businesses and interest groups. Let’s take just a moment to identify and categorize these actors.

Federal official actors

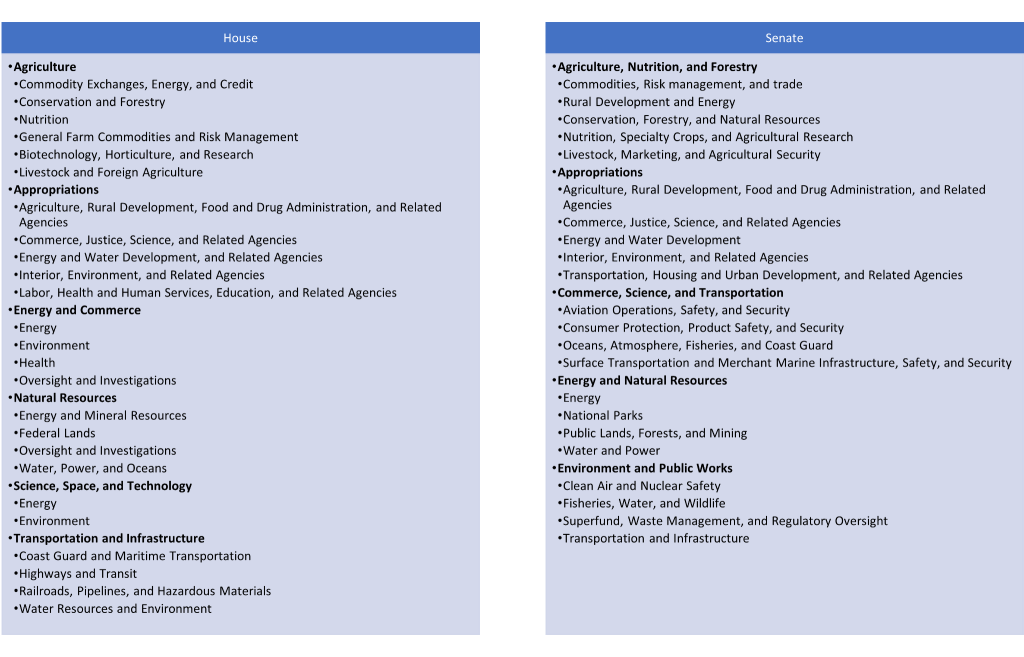

By one count, at least 28 House and 20 Senate committees and subcommittees have jurisdiction over environmental and/or energy policy.[31] In the House, the Energy and Commerce Committee and the Natural Resources Committee and in the Senate, the Energy and Natural Resources Committee and the Environment and Public Works Committee play particularly important roles in environmental policymaking. As chapter 4 described, the overlap in jurisdiction between committees and the imperfect alignment of topics between the House and the Senate makes policymaking difficult when the two chambers must pass identical language.

Figure 8.3: A sample of some of the many congressional committees that have jurisdiction over environmental policy

As I’ve already mentioned, there was relatively broad support for environmental policy in Congress in the 1970s and 1980s, but particularly beginning in 1994, the parties began to divide on the issue making it more difficult for Congress to act.[32]

Presidents and the executive branch have stepped into the void left by Congress.[33] Presidential impact comes through several mechanisms. Presidents can prioritize environmental policy through their policy agenda, their appointments to positions in government, their budget proposals, and through executive orders they issue.

Within the President’s inner circle, there are a few particular individuals who carry special weight when it comes to environmental policy. Within the Executive Office of the President, the Council on Environmental Quality, coordinates presidential efforts related to the environment. The CEQ was created through the National Environmental Policy Act in 1969 to advise the President about environmental issues. More recently, President Joe Biden created a new White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy through an executive order to coordinate domestic environmental policy making. Biden also created a new position within the Executive Office of the President: the U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate.

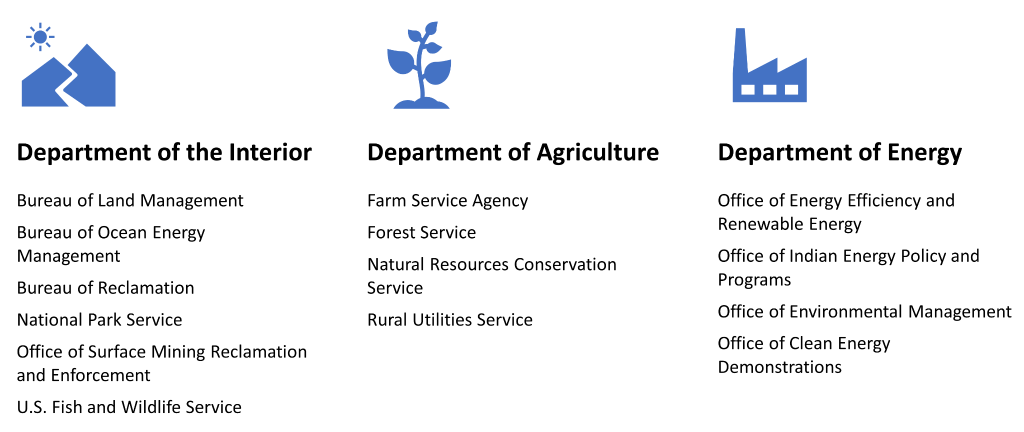

In the executive branch, at least 12 cabinet-level executive departments have some jurisdiction over environmental policy in addition to the Environmental Protection Agency and several other independent agencies, independent regulatory agencies, and government corporations.[34] The Department of the Interior plays a critical role in overseeing public lands and wildlife protection, while the Department of Agriculture oversees soil conservation efforts.[35] The Nuclear Regulatory Commission is an independent agency that oversees nuclear energy production but also has a mandate for protecting people and the environment.[36] The Tennessee Valley Authority is a government corporation that provides power but also monitors water quality.[37]

Figure 8.4: A sample of some of the executive agencies that have jurisdiction over environmental policy

And, of course, the Environmental Protection Agency is the leading federal agency overseeing environmental policy. The EPA is headed by an Administrator, a position appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Structurally, the EPA is headquartered in Washington, D.C. and has ten regional offices throughout the United States.[38] The EPA works closely with state environmental protection agencies and over half of the EPA’s annual budget is spent on grants to states and non-profit organizations.[39]

Bureaucratic actors both implement policy passed by Congress and create policy through the rulemaking process. For example, the EPA created more than 300 rules to implement the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990.[40]

Judges also play an increasingly important role in environmental policymaking. Judges determine legal standing, or who has the right to bring a lawsuit. In the U.S. legal system, you must be directly harmed in order to have legal standing in a case. This is important in environmental cases because the harm might not be obvious or direct. Judges also interpret the intent behind environmental policies.[41] Finally, judges can force the government to act, as was the case in Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency (2007), or prevent or delay the government from acting.[42]

Over the past few years, the Supreme Court has taken steps to restrict federal environmental efforts. Two cases in 2023, Sackett v. EPA and West Virginia v. EPA took a more conservative view of the EPA’s power to enforce the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act. And, in the 2024 Supreme Court Cases Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless, Inc. v. Department of Commerce, the Court overturned the Chevron doctrine, a 40 year precedent that gives federal agencies the right to interpret ambiguous federal laws through the rulemaking process.

State and local official actors

Each of the states has a roughly parallel set of official actors who are involved in environmental policymaking. State actors are particularly important in environmental policy because once the policies have been set, “much of the work is delegated to the states for implementation.”[43] The state actors are responsible for issuing most environmental permits and conducting most of the monitoring and enforcement. However, only about a quarter of state agency budgets comes from federal funding.[44] At least twenty states have a policy similar to the National Environmental Policy Act that requires an environmental impact review for all proposed state government projects and at least five states (including Minnesota) require environmental impact reviews for local government projects.[45]

Environment and energy committees within state legislatures help shape state environmental policies. Similar to the federal government, most states have multiple committees and subcommittees with jurisdiction over environmental issues.

In Minnesota, for example, House committees on Agriculture Finance and Policy, Climate and Energy Finance and Policy, Environment and Natural Resources Finance and Policy, and Sustainable Infrastructure Policy and Senate committees on Agriculture, Broadband, and Rural Development; Energy, Utilities, Environment, and Climate; and Environment, Climate, and Legacy all have environmental issues within their jurisdiction.

Similar to the President, governors can set the tone for environmental policymaking through their agenda choices, budget proposals, and executive appointments. Many states have developed a single agency to address environmental issues.[46]

In Minnesota, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, formed in 1967, is the main body overseeing environmental policy. The MPCA is led by a commissioner appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate. Other state agencies in Minnesota focused on the environment include the Environmental Quality Board, the Forest Resources Council, the Department of Natural Resources, the Office of Energy Security, and the Board of Water and Soil Resources.

Like federal judges, state judges can play a role in cases involving state environmental policies. Following the model of Juliana, multiple cases have been filed in state courts against state governments. Lawsuits in Hawaiʻi and Montana brought by young people argue that the state has an obligation to provide a “clean and healthful environment.”[47]

Finally, unlike the federal government, many states have an initiative, referendum, and/or constitutional amendment process that puts voters in the role of official actors in making policy. In 2022, voters passed seventeen policies at either the state or local level related to protecting the environment.[48] For example, voters in Minnesota in 2008 approved the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment to the Minnesota constitution. The Legacy Amendment increased sales tax and designated that the money be spent on environmental, historic, and artistic programs.[49]

Figure 8.5: Minnesota Legacy Amendment funds contributed to the construction of facilities for a herd of bison in Minneopa State Park. (Photo credit: Brian Knutson)

Unofficial actors

Unofficial actors play an influential role in environmental policymaking. Public interest groups, business groups, think tanks, and scientists contribute information and money to policy debates.

In his study of environmental advocacy groups, Bosso notes that “environmental advocacy at the national level in the United States is dominated by a loosely knit community of established organizations.”[50] Some of the largest and most well known include the World Wildlife Fund, the Sierra Club, The Nature Conservancy, The National Wildlife Federation, Ducks Unlimited, and Greenpeace. Some of these organizations fall more in the conservationist camp (Ducks Unlimited, for example), while others fall more in the preservationist camp (Greenpeace). According to the website OpenSecrets, in 2023, environmental advocacy groups spent over $30 million on lobbying efforts related to the environment.[51] Environmental groups also spent heavily on elections. In the 2020 election, donors affiliated with environmental groups contributed more than $57 million.[52] Some environmental organizations, like Earthjustice (whose tagline is, “Because the earth needs a good lawyer”), have particularly focused on legal strategies.

These public interest groups, however, face strong and well funded opposition from business interests. Oil and gas companies, chemical companies, and business groups have deep pockets. Koch Industries alone gave $27 million, almost entirely to Republican candidates and conservative interest groups in the 2022 election cycle.[53] Strong opposition to environmental policy comes from two interest groups in particular: the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers.[54] The American Petroleum Institute and the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers have also led efforts to curb regulation regarding vehicle emissions.

As the green energy sector develops, there is an emerging sector of business and industry trade groups in support of environmental policy. The American Council on Renewable Energy and the American Clean Power Association are just two examples at the national level. Minnesota Renewable Energy Society is an example of a non-profit organization advocating for the use of renewable energy in Minnesota. Groups representing these emerging industries, however, tend to have fewer resources to devote to lobbying or campaign efforts compared to the traditional energy sector.

Information about environmental problems and policy ideas comes from a range of research organizations, including think tanks and universities. The Natural Resources Defense Council brings together lawyers, scientists, and policy experts. Most major U.S. think tanks have a branch dealing with environmental issues, including the Brookings Institution, Heritage Foundation, and American Enterprise Institute. Many universities have research centers devoted to both environmental and environmental policy research.

In addition to advocacy groups and think tanks/research organizations, policymaking influence comes from the mass media and from individual citizens. Several news organizations focus specifically on the environment and clean energy. EcoWatch, Grist, and Inside Climate News are examples. Traditional news media often have sections devoted to environmental news. The New York Times, for example, has a Climate and Environment section.

Finally, individual citizens also play an important role in pressing the government to act. Younger people, in particular, view addressing climate change as a top priority for the government.[55] Citizen activists including former Vice President Al Gore, Winona LaDuke, and Xiuhtezcatl Martinez (pronounced Shoe-Tez-Caht) have each inspired public activism in their own way. And from the first Earth Day in 1970 to the People’s Climate March in 2014 and 2017, members of the public have found ways to communicate their support for environmental policy to policymakers.

One of the most visible examples of citizen activism began in April 2016 on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota as indigenous and environmental leaders joined together to protest the Dakota Access Pipeline. Using the hashtag #NoDAPL, protesters drew attention to their effort to halt the construction of an underground oil pipeline a half mile from the Standing Rock Reservation and within proximity to the Missouri River. Over 800 people were arrested over the course of the protests.

Figure 8.6: Rise and Repair, a coalition of organizations advocating for Indigenous rights and climate justice, pause on the steps of the Minnesota Capitol during their 2024 lobby and rally day. (Photo credit: Kate Knutson)

8.3 Why are we talking about this now?

Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework can help us understand and analyze the timing of policy action. In this section, we’ll use this framework to briefly explore a case where a policy window opened and one where it didn’t.

As I’ve already described, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 was the precursor to a wave of policy action in the early 1970s. In explaining the timing of this action, the Multiple Streams Framework calls us to examine the problem, politics, and policy streams.

The problem stream was active in the leadup to the NEPA. Biologist and writer Rachel Carson published an influential book in 1962 that became an immediate bestseller. Silent Spring explored the harmful effects of pesticides and blamed chemical companies for intentionally spreading false information. Not long after the book, several focusing events clearly illustrated the environmental problems she described. The Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio caught fire several times as a result of the toxic chemicals that had been dumped in the river. A picture of one of the fires was printed in Time and National Geographic in 1969, drawing national attention to water pollution.[56] Two major oil spills occurred off the coast of California in 1969 that also drew national attention. These focusing events, along with the indicators documented in academic studies and popular books helped to define environmental degradation as a problem in need of government action.

In the politics stream, the rising visibility of environmental advocacy groups and growing public opinion for environmental action helped to create favorable political conditions. Environmental advocacy groups shifted from a primarily educational strategy to a more political strategy beginning in the 1960s, including lobbying and engaging in political campaigns.[57] Polling data showed that the percent of people who said that “reducing pollution of air and water” should be a government priority grew from 17% to 53% between 1965 and 1970.[58] Although there wasn’t yet a strong partisan divide, Democrats controlled large majorities in both the House and the Senate from 1959 through 1980 making passage of policies in Congress a little easier. Control of the presidency changed from Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson to Republican Nixon in 1969, but though Nixon wasn’t a strong environmentalist, he recognized the political benefit of aligning with the public and congressional leaders on the issue.[59]

In the policy stream, Congress had spent nearly a decade debating establishing a national environmental policy and had discussed similar proposals. Members of the House and Senate met in 1968 for a joint meeting on the topic of creating a national policy for the environment.[60] These ideas coalesced into bills that were introduced in the Senate by Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-WA) (S. 1075 introduced on February 18, 1969) and in the House by John Dingell (D-MI) (H.R. 12549 introduced on July 1, 1969). The Senate held hearings in April of 1969. One of the witnesses in the Senate hearing was Dr. Lynton Caldwell, Professor of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University, and he is credited with introducing the idea of adding a provision for environmental impact statements during his testimony. The final version of the policy included this provision.[61] The Senate passed their version of the bill in July 1969 and the House passed a different version in September 1969. A conference committee met to address differences and both chambers reached agreement in late December.[62]

Kingdon’s framework helps us understand the passage of NEPA. Both the policy and the politics streams were favorable to passage, with policy ideas beginning to coalesce, strong public opinion, and congressional support. Indicators from the problem stream helped to develop support for a national environmental policy framework. The focusing events of 1969 (oil spills and national media coverage of the Cuyahoga River fires), however, helped open the window of opportunity for policy making by drawing the public’s attention to environmental problems and the need for government action.

Figure 8.7: The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act (1978) set aside over one million acres of protected land in northern Minnesota. The U.S. Forest Service reports that the BWCAW is the most heavily used wilderness area in the country, with about 150,000 visitors each year. (Photo credit: Brian Knutson)

The Green New Deal proposal offers a contrast to the successful passage of NEPA. The Green New Deal was a resolution introduced by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Senator Ed Markey (D-MA) on February 7, 2019. The resolution identified human activity as the dominant cause of climate change and extreme weather. The resolution proposed a ten year national mobilization to develop renewable energy, clean up hazardous waste, and overhaul transportation, among many other goals.

The problem stream in 2019 was less clear than it had been in 1969. On one hand, there was convincing scientific evidence (indicators) of warming temperatures caused by human activities. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Fifth Assessment Report, published in 2014, concluded “human influence on the climate system is clear, and recent anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gasses are the highest in history. Recent climate changes have had widespread impacts on human and natural systems.”[63] These indicators were dramatically emphasized through the growing number of extreme weather events in the U.S. In the first half of 2019, for example, there were six weather-related disasters in the U.S. that caused more than $1 billion in damages.[64] Taken together, these weather-related focusing events, coupled with scientific indicators seem to make it clear that there are environmental problems.

However, there is ideological and partisan disagreement as to the cause of the problem. Beginning in the 1980s, conservative think tanks helped to spread skepticism about scientific research concerning climate change.[65] Conservative media personalities provided a platform for these ideas in the 1990s and into the 2000s while corporate interests funded the work. Climate change denial has been most pronounced among Republicans. A Pew Research student found that in 2022, only 23% of Republicans and those who lean Republican view climate change as a major threat.[66] The end result is that there is not a clear consensus about the problem among all Americans. In addition to the partisan and ideological split. There is also a generational divide, with younger generations being more supportive of efforts to combat climate change.[67]

Additionally, in the politics stream, the proposal for the Green New Deal was introduced during a time of divided government. In 2019, Republicans controlled the Senate while Democrats controlled the House. The president at the time, Republican Donald Trump, strongly opposed the proposal.

In the policy stream, the ideas behind the Green New Deal originated from a youth activist group called the Sunrise Movement, which held sit-ins outside the office door of then-Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi in 2018. It also drew inspiration from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies during the Great Depression.[68] As a resolution rather than a bill, the Green New Deal did not articulate specific policies, but rather a broad series of goals combining environmental, economic, and social initiatives.

Kingdon’s framework helps us see that, unlike the case of NEPA, there was disagreement within the problem stream, unfavorable conditions within the politics stream, and a lack of clarity within the policy stream. Perhaps unsurprisingly, despite lots of media attention, the resolutions introduced by Representative Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Markey were not adopted by Congress.[69]

8.4 How is policy made?

Since regulation is one of the major policy tools used in environmental policymaking, this section describes the policymaking process for the regulation of PFAS or “forever chemicals” (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances). The EPA proposed regulating PFAS in drinking water in March 2023.

PFAS include about 600 chemicals used in commercial products such as nonstick pans, waterproof cosmetics, and takeout food containers. When these products are disposed of, the chemicals leach into the ground and eventually wind up contaminating soil and water. “Exposure to certain PFAS has been linked to increased risk of prostate, kidney and testicular cancer, fertility problems, developmental delays, reduced immune system function (including reduced vaccine effectiveness), increased cholesterol and obesity, ulcerative colitis, high blood pressure during pregnancy, hormone system interference and liver and thyroid problems.”[70]

The government first became aware of the potential harmful effects of PFAS in 1998, when scientists from the Minnesota company 3M discovered that PFAS can build up over time in the blood. However the first policy action wasn’t until 2002, when the EPA required manufacturers to notify the agency when they manufacture or import some PFAS chemicals.

In 2019, Andrew Wheeler, the EPA Administrator announced a PFAS Action Plan to research the effects of PFAS on human health and potentially limit human exposure to the chemicals.[71] The EPA continued to work on the issue, gathering and disseminating research and reporting data.

The EPA held two public meetings in the early months of 2022 to share preliminary information about the environmental justice considerations behind the development of a proposed rule to regulate PFAS in drinking water. They also accepted pre-proposal comments in spring of 2022.[72] This approach responds to the “growing calls for the regulatory approach to be more collaborative because environmental protection is achieved not by government alone, but through the partnership of government, the regulated community, and other public interests.”[73]

In February of 2023, the EPA announced that it would use $2 billion from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to address the problem of PFAS chemicals in drinking water. One month later, the EPA announced a proposed regulation on six PFAS chemicals under the Safe Drinking Water Act. The proposed PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (or PFAS NPDWR) began with publishing the proposed regulation in the Federal Register (this took 117 pages![74]) and opening a two month public comment period. The EPA also held multiple informational meetings and a public hearing. The proposed rule would set levels for six PFAS in drinking water, would monitor for those PFAS, would notify the public as to the levels of the PFAS, and would reduce the levels of PFAS if they went above the standard.

The EPA received over 1,600 comments during the open comment period from state and local governments, businesses, advocacy groups, and individuals.[75] At the end of the comment period, the EPA reviewed the comments and finalized the rule, sending it to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs within the Office of Management and Budget for review.

Once the regulation is finalized, state and tribal government agencies will implement the new regulations within their public water systems. The Safe Water Drinking Act gives these agencies three years from the date the regulation is finalized to fully comply with the regulation. This aligns with what Rinfret and Pautz tell us about most regulations dealing with environmental policy: “After the regulations have been promulgated, much of the work is delegated to the states for implementation; and typically,state environmental protection agencies assume primary responsibility for the implementation of these laws.”[76]

8.5 Why does policy look like this?

In 1979, sociologist Robert Bullard was asked to conduct a study of the location of city solid-waste disposal facilities in Houston, Texas to be used in support of a class action lawsuit filed on behalf of a group of neighbors who were facing the construction of a new landfill in their community.[77] During the process of researching the city’s decisions about where to locate new landfills, Bullard discovered that nearly all of the city’s landfills were situated within predominantly Black neighborhoods and that those neighborhoods had been established well before the landfills were placed there. Bullard wrote about this case and the larger issue of environmental racism in his book, Dumping in Dixie, first published in 1990.

Bullard defines environmental racism as “any policy, practice, or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages (whether intended or unintended) individuals, groups, or communities based on race or color.”[78] A large body of research supports Bullard’s claim that “the nation’s environmental laws, regulations, and policies are not applied uniformly; as a result, some individuals, neighborhoods, and communities are exposed to elevated health risks.”[79]

In recent years, more efforts have been taken to recognize and remedy cases of environmental racism in policymaking, but there are still many examples of policy failures. Continuing the theme of water quality, this section uses the Social Construction of Target Populations theory to briefly explore the water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

In April 2014 the city of Flint, Michigan switched its supply of city water from Lake Huron to the Flint River as a cost-savings measure.[80] The Flint River was heavily polluted, and city residents immediately began to complain about the water, saying that it looked, smelled, and tasted bad. Local officials tried treating the water with higher levels of chlorine, but the added chlorine further corroded Flint’s aging lead water pipes.[81] The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (now called the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy) was tasked with monitoring water quality, but did not require the city to have a corrosion control program. Subsequent evidence suggests that at least one agency employee altered data when reporting results to the EPA.[82] Nevertheless, city, state, and federal officials continued to maintain that the water was safe to drink.

Over the next year, scientific evidence began to mount that the water was not only unpleasant, but harmful. A research team from Virginia Tech began collecting water samples from Flint in August 2015 and the team announced in September that they had found substantial increases in lead levels. A local pediatrician also found elevated levels of lead in city children, finding that the levels of lead had doubled since the previous year.[83]

Figure 8.8: Drinking water pipes in Flint, Michigan (Source: VCU Capital News Source (CC BY-NY 2.0 DEED))

It wasn’t until October 2015, about 18 months after the switch to Flint River water, that Flint residents were advised not to drink the tap water and the Genesee County Health Department declared a public health emergency. Shortly thereafter, the city, state, and federal government each declared a state of emergency and devoted resources toward remedying the problem.

City and state officials worked to portray this as an accidental problem, while many residents and advocacy groups viewed it as an intentional byproduct of cost saving measures.[84]

Whether accidental or intentional causes are behind the situation, the Social Construction of Target Populations theory helps us analyze this case. Nearly 60% of Flint residents were Black[85] and 40% had income under the federal poverty line.[86] With an overall population of just under 100,000 people, the unemployment rate in the city was nearly 14% at the time of the crisis. The population was also significantly younger compared to the state as a whole and Flint residents were less likely to have completed education beyond high school compared to the state as a whole.[87] All in all, Flint was a town that was Blacker, poorer, younger, and less educated than many other Michigan towns. Given what we know about general trends in political power of these demographic groups, it is safe to conclude that Flint residents had, or were at least perceived as having, relatively low levels of political power.

In his study of the Flint water crisis, Pauli chronicles how in November 2011, a Michigan review panel declared Flint to be in the midst of a financial emergency due to a $30 million deficit and, as a result, the governor appointed an emergency manager to take over the executive and legislative functions of the city’s government. Ironically, the announcement came the same day as local elections when, “Flint voters learned that the person they were in the process of electing would be, institutionally speaking, powerless.”[88] From the perspective of state leaders, the city of Flint was viewed as a delinquent, having failed to be fiscally responsible.

The low level of political power held by Flint residents and the negative view of the town held by state leaders suggests that the target population (Flint residents) might best be classified as deviants under the Social Construction Theory. Deviants have little control over policymaking, which was certainly the case here as decisions were made by state-appointed actors rather than by city elected officials. Deviants receive few benefits and are likely to receive burdens. In this case, lead-contaminated water.

As the situation developed, two notable changes occurred. First, attention began to focus on the impact of the lead contamination on children. Research by Flint pediatrician, Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, was particularly important in drawing attention to the public health impacts on children. Several prominent news outlets including the Detroit Free Press, National Public Radio, and the Washington Post highlighted Dr. Hanna-Attisha’s research emphasizing the harmful effects of lead in children. Studies document that high levels of lead are associated with learning disabilities and problems with attention and fine motor coordination. An estimated 6,000-12,000 children were exposed to high levels of lead in their water in Flint. When attention shifted to the impact on children, it helped shift the target population from deviant to dependent. Government agencies declared a public health emergency and began providing money for water filters and water testing.

Second, Flint residents began organizing to demand government action. These self-proclaimed “water warriors” attended government meetings and protested outside city buildings.[89] A coalition of Black and white working class citizens raised media attention of the situation and social media hashtags like #FlintWaterCrisis and #HelpFlint helped to broaden the scope of conflict. The activists intentionally used the term “crisis” to describe what was happening in Flint.[90] Advocacy groups like the Coalition for Clean Water, Flint Democracy Defense League, and Flint Rising helped coordinate water testing efforts that confirmed the scope of the problem.[91] In June 2015, the Coalition for Clean Water filed a lawsuit alleging the city “recklessly endangered” the health and safety of residents. Activists protested the Governor’s 2016 State of the State address, calling for his resignation and arrest.[92] Through this mobilization, the citizens of Flint increased their political power, shifting the group into the advantaged category.

Flint’s water warriors weren’t just interested in stopping the tainted water, they wanted accountability through punishment of those responsible and reparations to repair the harms done to Flint residents.[93] Ultimately a state task force placed most of the blame on the MDEQ and concluded that “the Flint water crisis is a story of government failure, intransigence, unpreparedness, delay, inaction, and environmental injustice.”[94] Multiple government officials were also charged with various crimes, though to date, there have been no felony convictions related to the Flint water crisis.

Social Construction Theory helps explain why government actors made the choices they did and why they reversed course once the social construction and political power of the target population began to shift.

8.6 Does it work?

As with all public policy, it is important to ask whether environmental policy works (also known as an outcome evaluation). Federal agencies publish regular reports on the effectiveness of the major environmental policies. According to Rinfret and Pautz, “generally speaking, this form of regulation in the environmental area works and produces results.”[95] For example, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, since 1990 “there has been approximately a 50% decline [in the] emissions of key air pollutants.”[96] Similarly, since passage of the Clean Water Act, the number of bodies of water that were deemed unsafe for fishing has declined.[97] And, according to the World Wildlife Federation, 99% of the species that received protection under the Endangered Species Act recovered.[98]

That said, environmental problems persist. 2012-2021 was the warmest decade on record and we are beginning to see effects such as rising sea levels, more intense hurricanes and storms, droughts, heat waves, and longer wildfire seasons.

One challenge in evaluating environmental policies is that the costs of environmental protection are high. Therefore, one key question in evaluation efforts is whether the environmental benefits of a policy outweigh the economic costs (a cost-benefit evaluation). For example, several analyses of the Clean Water Act have found that the costs of the policy are higher than the benefits.[99] The tension between economic costs and environmental benefits of a policy is significant, but as with all evaluation, it is also difficult to measure. A policy evaluator can measure the change in an environmental outcome following the implementation of a policy compared to the cost of implementing the policy, but they also have to account for the fact that the environmental situation would not have remained constant in the absence of the policy.

A second major challenge in evaluating environmental policies is that the data are not always available. According to the Government Accountability Office, only about half of U.S. waters have been assessed for quality as of 2017.[100] The challenge of accessible data has been exacerbated under the second Trump administration, which has removed climate science data from federal websites, cut funding for climate science research at federal agencies, and ended the collection of future climate data.[101]

Policymakers faced with a decision over an environmental policy, then, may or may not have access to conclusive evaluation data. Policymakers within the bureaucracy are also relatively secluded from the opinions of the public since they don’t regularly interact with voters as do elected officials. When drafting regulation, bureaucrats are required to solicit information from experts and the public during a public comment period of usually 30-90 days. In the next section, we’ll explore how to write and submit a comment to a federal agency.

8.7 What is a public comment?

When federal agencies and most state agencies are in the process of developing regulations, there is an opportunity for members of the public to comment on proposed actions during a designated open comment period. Public comments may be short or long and they may come from an individual, an organization, or anonymously. They focus on a specific proposed regulation or are part of the process of developing a proposed regulation.

Public comments have one primary audience: the agency engaging in the rulemaking process with the goal of providing agency decision makers with relevant information as they shape the regulation. However, it’s important to remember that, for the most part, comments submitted to federal agencies are part of the public record and anyone can access them through Regulations.gov.[102]

The majority of comments federal agencies receive during open comment periods are what bureaucrats consider non-substantive and simply reflect either general support or opposition to the proposed regulation. While this does provide decision makers with information, it is important to remember that a comment is not a vote. “One well supported comment is often more influential than a thousand form letters”[103] Yes, the agency wants to know if you support or oppose the proposed regulation, but they are also seeking constructive feedback to help inform their decision making process.[104] The public comments that are most helpful are what bureaucrats call substantive comments. “The most valuable public comments are unique, fact-based, and succinct.”[105]

Experts within the agency carefully read through all of the substantive comments they receive during an open comment period and group them by topic or by the outline of the proposed regulation. Information learned through the public comment process is used by the agency to shape the final regulation.

The first step in making a public comment is to find something to comment on. At the federal level, this information is available on the website Regulations.gov. Here, the federal government posts proposed federal regulations and provides an opportunity for public comment.

You can use the search bar at the top of the page to search by topic, agency, regulation title, or docket number. A filter on the left side of the page allows you to narrow the results to documents that are open for comment.

Before you submit a comment, read the proposed regulation carefully. Be sure that you understand the proposed regulation that you’re commenting on. Each proposal will have contact information for a person in the agency who can answer questions you might have before submitting a comment.

Because regulations often use technical language, AI could be helpful in summarizing key ideas. Paste the regulation into an AI tool and ask it to summarize the main points in language that a high school student could understand.

Every proposed regulation has a name and a docket ID number. This information will be important to include when you write your comment and it will help you keep track of what happened to the proposed legislation.

Most agencies do accept paper copies of public comments, but it is much easier to submit your comments electronically. Using the Regulations.gov website, you can paste your comment directly into the submission form or upload it as a document using the blue “comment now!” button in the top right corner of the website. You can upload up to 20 files if you have supporting material to include in your public comment.

After submitting a public comment you can sign up through Regulations.gov to receive updates when the agency responds to the comments in the final rule. You will get a comment tracking number for your comment and can use this to find your comment on Regulations.gov. You won’t be able to see your comment immediately because it has to be processed by the agency first. It can take a few weeks to do this.

In your comment, you should include the regulation name and docket ID number in the subject line.

In the opening paragraph, you should clearly state your expertise and credentials in relation to the topic at hand. What experience do you have that makes you a particularly important voice to consider?

In the next paragraphs, present your information clearly and concisely. Are you raising concerns about the proposal? If so, what are those concerns? Are you informing the agency of new information? If so, what is that information? Are you providing evidence in support of a position? If so, what is that evidence?

The agencies will find it helpful if you consider trade-offs and opposing views as part of your analysis.[106] They are also interested in evidence, so you can and should include supporting evidence and a bibliography in a substantive public comment.

As with all policy writing, you should be clear, concise, and professional. Functionally, I’d recommend drafting your public comment in a separate document and then uploading it to the website rather than trying to draft your comment directly in the website.

The Public Comment Project, a nonprofit organization that promotes “evidence-based policy by facilitating scientists’ engagement in public comment on federal regulations”[107] suggests the following template to help structure your public comment:

Figure 8.9: Public comment template

| Re: [Docket ID Number]

To Whom It May Concern:

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on [Docket Title]. I am [1-2 sentences introducing yourself and your credentials].

I would like to [raise concerns / inform you of new information / provide supporting evidence] regarding [document title].

1st main point. [Develop argument and include references to supporting evidence in bibliography].

2nd main point. [Develop argument and include references to supporting evidence in bibliography].

…

In summary [1-2 sentences summarizing your comment].

Sincerely, [Name and affiliation]

Bibliography [Include list of sources cited]

|

8.8 Why do you write?

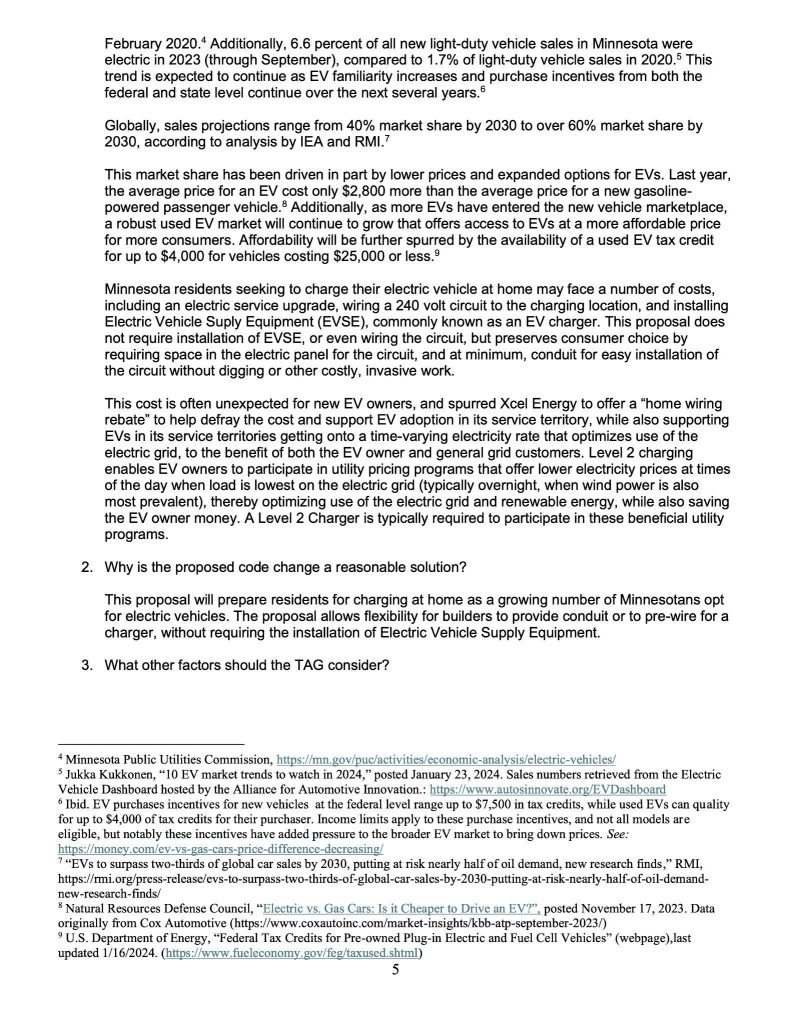

Figure 8.10: Eric Fowler (Halvorson) ‘13, Senior Policy Associate at Fresh Energy, in front of the Minnesota Capitol after testifying in support of a bill he helped develop (which is now law) to provide $6.5 million for electric panel upgrades.

My name is Eric Fowler (he/him), and I grew up in West Fargo, North Dakota to parents with a high school diploma and an associate’s degree. I’m a white, queer, neurodivergent person who didn’t have a clear idea where a political science degree might lead me, but knew I wanted to do something “activist-y.”

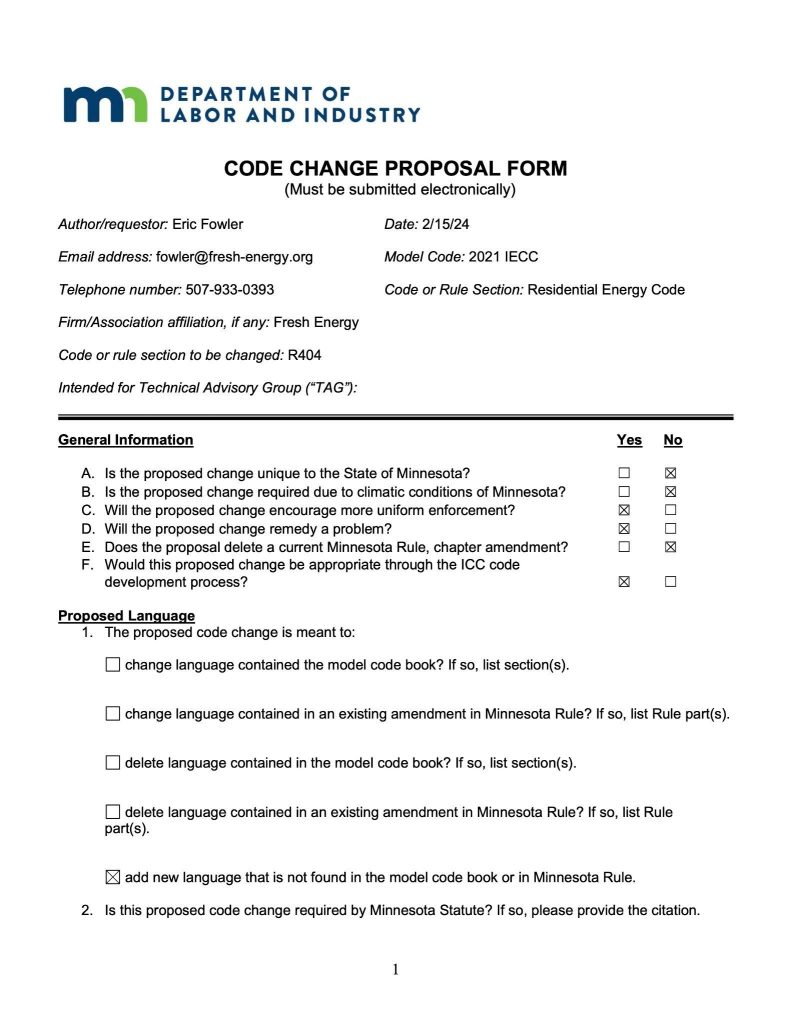

I graduated as Eric Halvorson in 2013 with a major in Political Science, minor in Religion, and an almost minor in French. While in Kate’s class, I joked that it was so much more “nutsy boltsy” than the political theory classes where I spent most of my time. Yet here I am, in a technical job focused on the nuts and bolts of policymaking. I’m a Senior Policy Associate for Buildings at Minnesota climate and energy policy nonprofit Fresh Energy. We’re about a 30 person organization, and I am responsible for our advocacy and policy positions on building energy codes, and support efforts to advance electrification and reduce fossil fuel combustion in our buildings. From late 2023 to early 2024, I was a voting member of the Technical Advisory Group convened by the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry to write the new residential energy code. Being part of technical policymaking processes is an excellent way to live out the values that my political theory classes helped to articulate.

I was privileged and lucky to break into this work without a master’s degree, thanks in part to my year of service during Lutheran Volunteer Corps at the Chicago Jobs Council in Illinois. I came on as a Policy Research Assistant before being hired on full time and gaining responsibilities for external communications and continued policy work. I spent much of my time in Chicago working to eliminate transportation barriers to employment, particularly by supporting legislation that ended driver’s license suspension as a collection tool for parking ticket debt.

Whether at Chicago Jobs Council or Fresh Energy, this work has varied widely across different days and seasons. Things are busiest for me during the legislative session, though some of my colleagues focus more on areas with different schedules like the Public Utilities Commission, administrative departments, or building community support for our issues. On a given week, I will have anywhere from 3 to 13 meetings or calls (including ~15 minute phone calls here–that’s not all 60 minute sit-downs). Other tasks include research, attending webinars and coalition calls, reading relevant news and reports, presenting at or attending a conference, or staring at a spreadsheet trying to estimate how many homes might benefit from a $6.5 million state investment in residential electric panel upgrades.

One constant is writing. From sharing meeting notes to suggesting edits on a bill draft, I am always working with words. Sometimes it’s more academic, like preparing an argument full of citations for public comment to an agency. Other times it’s soundbites, like writing talking points for myself before an interview or for a legislator before a bill introduction. While I have a love/hate relationship with emails, they are a huge portion of my writing. Well written and organized emails keep advocates and the partners we work with coordinated, informed, and better prepared for critical opportunities to influence policy outcomes.

My writing process has evolved a lot, and changes depending on the product. Once I swore by pen and paper. Now, most of my writing happens on the computer. Occasionally I even like the narrow focus of working on my phone where I cannot practically split my screen or keep flipping between tabs.

My first drafts, especially in persuasive writing, tend to be exhaustive and without order. I throw everything at the wall, dropping in quotes and citations I want to use, and rambling until I’ve repeated each point at least 2 different ways. Then I take a break, come back with fresh eyes, and start to organize my thoughts. This may not sound like it’s conducive to starting with an outline, because it is not. I’ve gotten better about outlining where I want to go over time, but I don’t always know what I’m trying to say until I’ve written it, so when I do use an outline, it often changes a lot.

There are two pieces of advice I would share with someone starting in public policy or a writing-heavy field. First, stay curious, and be adaptable when you learn more. Working to advance more energy efficient buildings at the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry, I once wrote out an extensive argument about the need for a stricter building energy code in order to meet state carbon emission reduction goals. Then, I learned that the Department can’t justify code updates based on climate goals. Minnesota law established the building code “for health, safety, welfare, comfort and security of the residents of this state and [to] provide for the use of modern methods, devices, materials and techniques which will in part tend to lower construction costs.”

Before a code update goes into effect, an Administrative Law Judge will review a statement of need and reasonableness that must justify the changes based on statute. That statute doesn’t include carbon or climate change, and key staff do not understand their authority to include them. After better understanding my audience and the statute they’re bound by, I have learned to ground my leading arguments in this venue with comfort, welfare, health, and safety, and emphasize that using “modern methods, devices, materials and techniques” means requiring extremely efficient new homes. Climate change is still my and my organization’s reason for being there. But when I include the argument to the department, it goes last as a final appeal, only after I have provided my audience with the most statutorily relevant justifications for the changes I hope to advance in the energy code.

The second piece of advice is simpler: take breaks! Writing may not be manual labor, but it’s still physical. I have dealt with chronic wrist pain since Gustavus. Pay attention to your body and learn about ergonomic adaptations. Move, stretch, and try not to sit all the time, especially in the same chair.

Figure 8.11: This is a code change proposal to make all new homes ready for electric vehicle charging that was written by Eric Fowler and submitted to the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry.

Glossary

Chevron doctrine: Legal precedent that gives federal agencies the right to interpret ambiguous federal laws through the rulemaking process.

Clean Air Act: Federal law that created air quality standards and regulates air pollution to protect human health and the environment.

Clean Water Act: Federal law that created water quality standards and regulates point source pollution.

Collective action problem: A situation in which everyone would be better off if they worked together to achieve a goal, but their conflicting interests and personal self interest keep them from doing so.

Conservationist: Perspective on environmental policy that promotes the wise use of natural resources by humans.

Council on Environmental Quality: Office within the Executive Office of the President that coordinates presidential efforts related to the environment.

Endangered Species Act: Passed in 1973 to protect wildlife (animals and plants) at risk of extinction.

Energy policy: Government action, or inaction, related to production, distribution, and consumption of energy.

Environmental policy: Government action, or inaction, related to the natural environment.

Environmental Protection Agency: Federal agency responsible for protecting human health and the environment.

Environmental racism: Any policy, practice, or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages (whether intended or unintended) individuals, groups, or communities based on race or color.

Green New Deal: Unsuccessful resolution introduced in 2019 to identify human activity as the dominant cause of climate change and to propose a national mobilization to develop renewable energy, clean up hazardous waste, and overhaul transportation systems.

Inflation Reduction Act: Passed in 2022, this was the largest investment by the U.S. federal government into climate-related policies in U.S. history.

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency: The primary state-level agency in Minnesota overseeing environmental policy.

National Environmental Policy Act. Passed in 1969 to establish a national environmental policy for the United States and require an environmental impact review for federal actions.

Non-point source pollution: Pollution that comes from multiple locations like stormwater runoff.

Paris Climate Agreement: International plan negotiated in 2015 to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The U.S. signed on to the agreement in 2015, withdrew from it in 2016, and rejoined it in 2021.

Point source pollution: Pollution that comes from a single point like a factory.

Preservationist: Perspective on environmental policy that promotes the complete protection of nature and wild areas.

Public comment: Communication to the government regarding a proposed regulation.

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act: Passed in 1976 to monitor the generation, transportation, storage, and disposal of hazardous waste.

Safe Drinking Water Act: Passed in 1974 to set national standards for drinking water quality.

Superfund (Comprehensive Environmental Response and Liability Act): Passed in 1980 to coordinate and fund toxic waste cleanup efforts around the country.

Tragedy of the commons: One type of collective action problem in which people who have access to a common resource act in their own self interest by using the resource, which negatively impacts access to, or the quality of, the resource for others.

Wilderness Act: Passed in 1964 to preserve land for federal protection.

Additional Resources

Websites

Environmental Council of the States (https://www.ecos.org/) Nonprofit, nonpartisan association of state environmental agency leaders.

Environmental Law Institute (https://www.eli.org/) Nonpartisan think tank focused on environmental policy

National Conference of State Legislatures (https://www.ncsl.org/environment-and-natural-resources) Research on state legislative efforts related to environmental policy.

National Surveys on Energy and the Environment (https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/100167/version/V19/view;jsessionid=81A9F0389449860EF8CE6A7101BB9CBE) Biannual survey exploring national public opinion on a variety of environmental topics starting in 2008.

Pew Research Center (https://www.pewresearch.org/topic/international-affairs/international-issues/environment/) Public opinion data on environmental issues with more of an international focus.

Regulations.gov Website that tracks the development of federal regulations and other regulatory documents and allows the public to submit comments.

Resources for the Future (https://www.rff.org/) A nonprofit think tank focused on environmental policy.

State Energy and Environmental Impact Center (https://stateimpactcenter.org/) Nonpartisan university research program focused on state environmental efforts.

Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/) University research program focused on public opinion and behavior related to environmental issues.

Books

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company. 1962.

Rinfret, Sara R. and Michelle C. Pautz. U.S. Environmental Policy in Action, Second Edition. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Vig, Norman J., Michael E. Kraft, and Barry G. Rabe (Eds.). Environmental Policy: New Directions for the Twenty-First Century, Eleventh Edition. Los Angeles: Sage/CQ Press, 2022.

Documentaries

Thanks for reading this chapter. The book in which this chapter sits is a work in progress and I welcome feedback and suggestions for improvement. If you notice incorrect or out of date information, please let me know using the feedback form linked below. If something was particularly helpful to you, I’d also love to hear about it. If you are a faculty member or public policy practitioner who is interested in collaborating on this project, you can also use this feedback form to contact me. ~Kate

Feedback form: https://forms.gle/LKBykHHRLe2kNW2AA

- Read more about Nathan here: https://news.blog.gustavus.edu/2021/02/25/nathan-baring-named-finalist-for-truman-scholarship/ or here: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/dec/31/alaska-youth-climate-change-activist-nathan-baring-lawsuit-fossil-fuel-government ↵

- Youth v. Gov is a 2020 documentary about this case that is available to watch on Netflix. ↵

- Sara R. Rinfret, Denise Scheberle, and Michelle C. Pautz. Public Policy: A Concise Introduction (California, Sage/CQ Press, 2019), 237. ↵

- I’m planning a separate policy chapter focused on energy policy. ↵

- Carter A. Wilson, Public Policy: Continuity and Change, 3rd Edition (Illinois: Waveland Press, 2019). ↵

- Carter A. Wilson, Public Policy: Continuity and Change, 3rd Edition (Illinois: Waveland Press, 2019). ↵

- Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1965). ↵

- Other types of collective action problems are free riding (see the chapter on health care policy) and the prisoner’s dilemma (see the chapter on criminal justice policy). ↵

- Michael E. Kraft and Norman J. Vig, “U.S. Environmental Policy: A Half-Century Assessment.” In Environmental Policy: New Directions for the Twenty-First Century, 11th Edition, eds. Norman J. Vig, Michael E. Kraft, and Barry G. Rabe (California: Sage, 2022), 6. ↵

- National Environmental Policy Act, 42 U.S.C. 4331(a) ↵

- U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Clean Air Act: A Summary of the Act and Its Major Requirements, RL30853, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL30853 ↵

- Kimberly Smith, “Environmental Policy in the Courts,” in Environmental Policy: New Directions for the Twenty-First Century, 11th Edition, eds. Norman J. Vig, Michael E. Kraft, and Barry G. Rabe (California: Sage, 2022), 137-154; the EPA’s regulatory power was limited by the more recent Supreme Court ruling [pb_glossary id="731"]West Virginia v. EPA[/pb_glossary] (2022) in which the Court ruled that the EPA does not have the power to issue regulations across the power sector. ↵

- U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Clean Water Act: A Summary of the Law, by Claudia Copeland, RL30030 (2016), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL30030.pdf ↵

- “Overview of the Safe Drinking Water Act,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, last updated February 14, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/overview-safe-drinking-water-act. ↵

- “Law and Policy,” National Park Service, last updated November 16, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/wilderness/law-and-policy.htm. ↵

- “The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976,” The Bureau of Land Management, last accessed February 20, 2024, https://www.blm.gov/sites/default/files/AboutUs_LawsandRegs_FLPMA.pdf ↵

- U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Federal Land Management: When “Multiple Use” and “Sustained Yield” Diverge, LSB10982 (2023), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10982 ↵

- “EPA History: Resource Conservation and Recovery Act,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, last updated June 7, 2023, https://www.epa.gov/history/epa-history-resource-conservation-and-recovery-act. ↵

- “Superfund: National Priorities List (NPL),” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, last updated October 20, 2023, https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-national-priorities-list-npl. ↵

- “Summary of the Endangered Species Act,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, last updated September 6, 2023, https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-endangered-species-act. ↵

- The total bill authorized 7 billion. Christina Romer, “Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on the Clean Energy Transformation,” April 22, 2010, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2010/04/21/impact-american-recovery-and-reinvestment-act-clean-energy-transformation#:~:text=Column 1 shows that of,devoted to clean energy programs. ↵

- “Summary of Inflation Reduction Act Provisions Related to Renewable Energy,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, last updated October 25, 2023, https://www.epa.gov/green-power-markets/summary-inflation-reduction-act-provisions-related-renewable-energy. ↵

- “Investing in American Energy,” U.S. Department of Energy, August 16, 2023, https://www.energy.gov/policy/articles/investing-american-energy-significant-impacts-inflation-reduction-act-and. ↵

- Alejandra Borunda, Jeff Brady, Michael Copley, Rebecca Hersher, Julia Simon, and Lauen Sommer, “Countries Are Gathering For Climate Negotiations,” NPR, November 10, 2025 https://www.npr.org/2025/11/10/nx-s1-5601876/trump-cop30-climate-brazil-belem ↵

- Lydia Saad, “A Steady Six in 10 Say Global Warming’s Effects Have Begun,” Gallup, April 20, 2023. https://news.gallup.com/poll/474542/steady-six-say-global-warming-effects-begun.aspx ↵

- Michael E. Kraft and Norman J. Vig, “U.S. Environmental Policy: A Half-Century Assessment,” In Environmental Policy: New Directions for the Twenty-First Century, 11th Edition, eds. Norman J. Vig, Michael E. Kraft, and Barry G. Rabe (California: Sage, 2022), 3. ↵

- “Executive Order 12898 of February 11, 1994, Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations,” Federal Register, vol. 59, No. 32 (February 16, 1994). ↵

- Barry G. Rabe, “Racing to the Top, the Bottom, or the Middle of the Pack? The Evolving State Government Role in Environmental Protection,” in Environmental Policy: New Directions for the Twenty-First Century, 11th Edition, eds. Norman J. Vig, Michael E. Kraft, and Barry G. Rabe (California: Sage, 2022), 45. ↵

- “The Paris Agreement,” United Nations Climate Change, last accessed February, 20, 2024, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement. ↵

- “Paris Climate Agreement,” The White House, January 20, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/20/paris-climate-agreement/. ↵

- Michael E. Kraft and Norman J. Vig, “U.S. Environmental Policy: A Half-Century Assessment,” in Environmental Policy: New Directions for the Twenty-First Century, 11th Edition, eds. Norman J. Vig, Michael E. Kraft, and Barry G. Rabe (California: Sage, 2022), 3-33. ↵

- Michael E. Kraft, “Environmental Policy in Congress,” in Environmental Policy: New Directions for the Twenty-First Century, 11th Edition, eds. Norman J. Vig, Michael E. Kraft, and Barry G. Rabe (California: Sage, 2022), 111-136. ↵

- Norman J. Vig, “Presidential Powers and Environmental Policy,” in Environmental Policy: New Directions for the Twenty-First Century, 11th Edition, eds. Norman J. Vig, Michael E. Kraft, and Barry G. Rabe (California: Sage, 2022), 87-110. ↵

- Sara R. Rinfret and Michelle C. Pautz. U.S. Environmental Policy in Action, 2nd Edition. (Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 136. ↵