2 Who Are the Players?

Katherine Knutson and Jessica Flannery

Wondering why some text is in blue? Click here for more information.

2.0 Who makes public policy?

There are a lot of different individuals and organizations involved in the policymaking process. We call these players “actors.” Some actors are government employees whose involvement comes as a result of their official position, while others operate from outside of government. Actors that have an authorized role to play in the policymaking process based on the Constitution or statute (law) are called official actors. Official actors might include elected officials or unelected bureaucrats; the key distinguishing feature is that they have the authority to make a policy decision in a particular case.

Unofficial actors also have an interest in policy outcomes and work hard to influence policy outcomes, but lack the legal standing to actually make a policy decision. Unofficial actors are always going to be unofficial because they do not have the legal authority to make policy decisions. However, an individual or organization might be an official actor in one context, but an unofficial actor in another. For example, a mayor would be operating as an official actor in policy decisions controlled by the city in which they serve as mayor; however, they would be operating as an unofficial actor if they were trying to influence a state-level policy under consideration by the state legislature that would impact the city. Let’s take a minute to dig into these two categories of actors to identify the main actors within each category that seek to influence public policy.

2.1 Who are the official actors?

One of the defining features of the political system is that it is a federal system. Federalism means that powers are split between two or more levels of government. In the U.S., power is shared between the national (federal) government and the 50 state governments. Within states, power is shared between the state and various local governments (counties, cities, townships, etc.). At each level of government, power is further split between different branches of government, a principle called the separation of powers. The federal government and the states have three branches of government: legislative, executive, and judicial. Divisions exist at the local level as well. Each of these centers of policymaking power are called venues. The U.S. Supreme Court is a federal judicial venue and the Minnesota legislature is a state legislative venue. Each venue has specified powers and jurisdiction when it comes to making public policy.

All of these venues create the space for a lot of people to work for the government and who might play a role as an official actor. Remember that the individuals I mention in this section aren’t always operating as official actors, but the nature of their position means that they regularly function as official actors. We’ll review some of the main actors at the federal level first and then summarize some of the main actors at the state and local levels. At this point, I will primarily focus on the individuals and organizations so that you are familiar with the actors; we’ll look at the process in more detail in subsequent chapters.

Federal Level

At the national (federal) level, actors come from the three main institutions: Congress, the Executive Branch, and the federal courts. In addition to identifying the main positions within each branch, it is important to think about the demographics of the individuals who serve in these positions, since they have power over political decisions.

Congress

Members of Congress include the 100 elected Senators (two from each state) serving in the U.S. Senate and 435 elected Representatives (based on population) serving in the House of Representatives. Senators serve in the Senate and are elected to six year terms; one third of the Senate is up for election in even years. Representatives serve in the House of Representatives and are elected to two year terms. They serve a particular geographical district within a state (except in small states, where they represent the entire state). Every state is guaranteed two Senators and at least one Representative, regardless of their population size.

There are six additional non-voting members of the U.S. House of Representatives to represent the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the four U.S. territories: American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Marianas Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. These positions are non-voting because only states are allowed to have full voting representation in Congress. Many people don’t realize that there are two additional delegate positions that have been outlined in treaties but not yet filled; one delegate to represent the Cherokee Nation and one to represent the Choctaw Nation. Delegates have some voting rights in Congress, but are not allowed to vote on final passage of bills.

Among legislators, there are certain individuals who have more influence over the policymaking process as a result of their position. Leaders in each chamber (the Speaker of the House, majority leader, and minority leader in the House and the Majority and Minority leaders in the Senate) have a lot of power to control the agenda of items that come up for discussion and votes. Similarly, committee chairs and ranking members (the highest ranking member of the minority party in each committee) exercise gatekeeping power within the committee.

In addition to the 541 elected members of Congress, there are over 10,000 people who work as congressional staffers, either for individual members or with committees. These individuals are not elected and they don’t cast votes, but they serve as an extension of the members on many policy actions.

Figure 2.1: Gustavus political science graduates, Nate Long ’16 and Marcus Schmit ’07 in front of Representative Tim Walz’s Washington office in the Rayburn House Office Building. Long and Schmit both worked as congressional staffers as one of their first jobs after graduating from Gustavus.

Congress serves three primary functions. First, it legislates, meaning that it proposes, debates, and passes (or fails to pass) legislation that creates and funds public policies. The details of how it does this are discussed in chapter 5. Second, Congress provides confirmation for positions within the executive and judicial branch. This happens in the Senate, where nominees are reviewed by various committees and then voted on by the full chamber. Finally, Congress provides oversight to the other branches of government. These oversight functions were established in the U.S. Constitution to provide checks and balances in the political system. Congress can check the power of the executive by overriding vetoes (requiring a 2/3rds vote in both chambers), providing advice and consent on presidential nominations to the bureaucracy and the courts, approving the federal budget and appropriations (authorization to spend money), ratifying treaties, and, in extreme cases, impeaching and removing people from office, including the president and Supreme Court justices.

Figure 2.2: Gustavus students meet with Representative Jack Bergman ‘69 (MI-01) in a committee room for the Committee on Veterans Affairs in January 2017.

In addition to these formal roles outlined by the Constitution, Congress provides representation, meaning it reflects the voices and viewpoints of the people in the decision making process. Members of Congress view their role as representative differently. Some see themselves as primarily meant to represent the policy interests of those who elected them (this is called substantive representation). Others view themselves as representatives of people who share their demographic characteristics, regardless of the district or state in which they reside (this is called descriptive representation). Some are deeply loyal to a political party, while others care more about ideology, particular policies, or the places they are from.

A majority of members of Congress are white men, but that has changed in recent years. The 118th Congress (2023-2025) is the most racially and ethnically diverse Congress ever elected. 26.9% of the House and 12% of the Senate identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, or Native American.[1] There are 17 immigrants serving in the House and one in the Senate[2]. Despite these gains, whites make up 59% of the U.S. population but still account for 73% of Congress.

In terms of gender, there are more women in the current Congress than at any other time in history.[3] 128 women serve in the House (including three women delegates) and 25 women serve in the Senate.[4] Women make up 28% of Congress compared to just over 50% of the population. There are also 13 LGBTQ members of Congress, which is an increase from the previous congress.[5]

Information about the demographics of congressional staff is a little harder to come by. A survey of staff working for Senate Democrats reveals that the number of staff from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups has increased to 35% from 29% in 2020.[6] A survey of top staff positions in the U.S. Senate found that 7.9% of Senate staff directors identify as people of color and 3.6% of top committee staff positions are held by people of color.[7] Analysis by the Washington Post found that 45% of House staffers are women, though women were less likely to occupy top positions in the office (like Chief of Staff or Legislative Director) and more likely to occupy positions like Scheduler, Caseworker, and Office Manager (95% of House Office Managers were women).[8]

The Executive Branch

In the executive branch, the President is obviously an important official actor (remember that presidents might also serve as an unofficial actor when they’re trying to influence policy at the state or local level or even when they’re trying to influence the policy decisions of other federal actors). The President is elected through the Electoral College to serve a four year term of office (2 full terms, maximum). The president serves military and diplomatic roles, like being Commander in Chief of the armed forces and negotiating treaties. The President also serves executive functions such as appointing individuals to some government positions, issuing pardons, and issuing directives through executive orders. The primary executive function of the President is implementing and enforcing the laws passed by Congress. The President can even serve some legislative functions through agenda setting (more on this in the next chapter), and signing or vetoing legislation.

Like Congress, the President has a lot of staff who work to shape and influence policy, including the Executive Office of the President, and the Cabinet.

Figure 2.3: Gustavus students pose for a photo outside the White House in January 2009

The Executive Office of the President was created in 1939 to provide the President with expert advisors. It includes the people who work directly in the White House Office as well as those in the Office of Management and Budget, the national Economic Council, the Domestic Policy Council, the National Security Council, and other organizations. Of these, the Office of Management and Budget is particularly important because it is responsible for preparing the president’s annual budget proposal and it reviews all proposed bills and agency regulations.

The Cabinet is composed of the Vice President and the leaders of the main executive branch departments. It serves an advisory role only and does not have the power or authority to make decisions on its own. Many members of the Cabinet oversee the fifteen major administrative units in government called executive departments: Agriculture; Commerce; Defense; Education; Energy; Health and Human Services; Homeland Security; Housing and Urban Development; Justice; Labor; State; Interior; Treasury; Transportation; and Veterans Affairs. The people who lead each of these departments are called Secretaries (except for the head of the Department of Justice who is called the Attorney General). They are nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, but they serve at the pleasure of the President.

No woman has been elected President, and Kamala Harris is the first woman, Black person, and Asian person elected Vice President. Barack Obama is the only Black person elected to serve as President to date. Charles Curtis was the only person with Native American ancestry to serve as Vice President (1929-1933).[9] All other presidents and vice presidents have been white men. Among cabinet officials in the Biden administration, about 55% are people of color and 45% are women.[10] Comparatively, President Donald Trump’s cabinet was 18% people of color and 18% women.

The executive branch also includes other agencies, bureaus, boards, and commissions. Some smaller agencies are housed within the larger executive department agencies. For example, the Office of Minority Health operates within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A group of Independent Agencies oversee specific government operations such as elections (the Federal Election Commission) or space exploration (NASA). Other independent agencies called Independent Regulatory Agencies, oversee specific economic activities (such as the Securities and Exchange Commission or the Consumer Product Safety Commission). Leaders of both types of independent agencies are nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, but they are protected from removal by the president for political reasons. Independent Regulatory Agencies often have 5-7 leaders who serve for fixed, staggered terms that go beyond a presidential term and some of these agencies are required by law to have a bipartisan membership.

Finally, there are government corporations, or businesses established by Congress that perform some type of public service that could theoretically be performed by a private business. Some examples include the U.S. Postal Service and Amtrak. The President nominates, and the Senate confirms, people to serve on leadership boards.

There are about 2.7 million federal civilian employees and the military employs about 1.4 million people. This means that the executive branch employs more than four million people. Of these, about 70% work for defense and security-related agencies like the Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Veterans Affairs. Even though 4 million people is a very big number, proportionate to the population, the size of the federal government has actually decreased over the past 50 years. Another interesting fact is that most federal employees (85%, in fact) work outside of the federal capitol in Washington, D.C. All of these people who work for government agencies in the executive branch are called bureaucrats. That term can sometimes be used pejoratively, but it just means the people who work for a government agency.

Early in the country’s history, positions in the federal government were awarded based on personal relationships and party loyalty, a system called patronage. Beginning in the 1880s with the passage of the Civil Service Reform Act in 1881, the system changed to a merit-based system called the Civil Service System. This means that most federal jobs (about 90% of them) require a person to have expertise in the topic and be qualified to hold the position and it also means that most federal bureaucrats hold the job regardless of the president in power and they are protected from being fired for political reasons. In turn, they are also prohibited from engaging in many forms of partisan political activity through the Hatch Act. This civil service system creates a lot of stability in the federal workforce.

There are, however, still several layers of leadership positions that are political appointees and about 1,200 positions that require Senate confirmation. These upper-level management positions are partisan because they are appointed by the president, and they can set the tone for the department or agency, particularly in terms of deciding where to focus attention and resources.

As of December 2020, people of color make up about 38% of the full-time federal workforce and women make up 44%.[11] The federal bureaucracy is one of the most diverse parts of government and is more diverse than many employers within the private sector. This is the direct result of intentional efforts on the part of the government to diversify its workforce that began in the 1940s and expanded in the 1970s in the wake of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[12] It is illegal for federal agencies to discriminate against employees and job applicants on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, disability, or age. In addition to proactive efforts to recruit workers from underrepresented groups, those workers benefited from the merit-based system, which made it more difficult to discriminate in hiring based on race, ethnicity, or gender. This is not to say that the federal bureaucracy is entirely without flaws when it comes to diversity; people from underrepresented groups are not well represented in supervisory positions.

The Judicial System

Finally, the federal court system is an important official actor. There are nearly 900 federal judges who are nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. The U.S. federal court system has three levels. Most cases originate at the local level in one of 94 district courts staffed by 673 district court judges. The next level is the 13 appellate courts in the federal system staffed by 170 judges. Finally, the U.S. Supreme Court is staffed by 9 justices.

Individuals are nominated by the President to a judicial position and those nominations must be confirmed by a majority vote of the U.S. Senate. Those who have been nominated and confirmed serve either as judges (at the district and appellate levels) or justices (at the Supreme Court…the leader of the Supreme Court is called the Chief Justice) until they choose to retire, they die in office, or they are removed by Congress through the impeachment process.

Among all federal judges, 74% are white and 67% are men.[13] The low numbers of women and people of color in the federal judiciary reflects that fact that judges and justices do not have term limits and many were appointed decades ago. Under President Obama, about 36% of judicial appointees were people of color and 42% were women. Under President Trump, about 16% of judicial appointees were people of color and 24% were women. In the first year of President Biden’s administration, 78% of his judicial appointees were women (32) and 63% (26) were people of color.[14]

Of the 116 justices who have served on the U.S. Supreme Court, 108 have been white men. Six women have served on the Supreme Court, with the first being Sandra Day O’Connor, confirmed in 1981 and the most recent being Kentaji Brown Jackson, confirmed in 2022. The other women are Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Amy Coney Barrett. Three Supreme Court justices have been African American: Thurgood Marshall appointed in 1967, Clarence Thomas, and Kentaji Brown Jackson. Sonia Sotomayor, confirmed in 2009, is the first and only justice of Latinx descent.

Figure 2.4: Current members of the U.S. Supreme Court: Front row, left to right: Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., Associate Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., and Associate Justice Elena Kagan. Back row, left to right: Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. Photo credit: Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Trump Era

The election of President Donald Trump in 2024 has resulted in substantial changes to the actors and roles described above. It is unclear if these changes are temporary or permanent and so, for now, I’ve chosen to simply highlight three areas in which the current political environment deviates from historical trends in this section.

First, the line between official and unofficial actors has blurred under the Trump administration. The role of businessman Elon Musk is a prime example. Musk was categorized as a “special government employee” leading a newly developed Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) tasked with cutting federal spending. Rather than simply serving in an advisory capacity (as an unofficial actor), Musk led efforts to dismantle government agencies such as the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Department of Education. White House Assistant Chief of Staff Stephen Miller has played a similarly ambiguous role in regard to immigration policy.

Second, execution of the separation of powers and checks and balances outlined in the Constitution has shifted. The executive branch has taken a significantly larger role in policymaking. Most of these actions have come through traditional means of presidential power such as executive orders. For example, Trump signed 26 executive orders on his first day, including banning diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in federal agencies and ordering a temporary pause of federal grants and loans. Trump also used his executive power to pardon most of the people charged in the January 6 insurrection. For other actions, Trump has invoked existing law to justify his unilateral actions. For example, in defending his decision to send troops to U.S. cities like Los Angeles, Washington, D.C. and Portland, the administration cites a 1903 law that allows the president to federalize National Guard troops to combat a “rebellion or danger of a rebellion” within the U.S. (10 U.S.C. §12406)..Similarly, Trump points to laws such as the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 as legal justification for unilateral action to enact high tariffs on goods manufactured in other countries.

In contrast, the 119th Congress has done little in the way of policymaking. The most significant policy passed by Congress was P.L. 119-21, commonly known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. This law significantly increased spending for border enforcement and deportations, cut spending to Medicare, expanded work requirements for SNAP benefits (food stamps), expanded tax cuts and deductions, and terminated clean energy tax credits. In general, Congress has deferred to presidential power, even in cases where the Trump administration has refused to comply with laws passed by Congress or spending authorized by Congress. Rather than serving as a check on presidential power, the Republican-led Congress has largely supported Trump’s expansion of political power.

The Courts have had a mixed response. Many of Trump’s actions have been challenged in court, with lower courts deciding to temporarily block administrative actions. The first substantial round of challenges to Trump policies reached the Supreme Court in 2025, with decisions expected in 2026. The scope of presidential power will be shaped by those decisions. However, it is also important to note that the Trump Administration has openly defied court orders and there is no mechanism for the Supreme Court to enforce its rulings.

Third, executive actions have changed the players in government. Trump took immediate steps to reduce the size of the federal workforce. The administration fired around 55,000 probationary employees not covered by civil service protections. Federal workers were offered buyouts to retire/resign, which over 150,000 did. In addition to a reduction in official actors, personnel in some offices that have generally been apolitical, such as in the Justice Department and in Inspector General positions, have been removed and replaced by Trump loyalists. Finally, the Trump administration has attempted to remove government officials from appointed positions in independent agencies before their terms expire. All of these personnel decisions have been challenged in court and most of those cases are still working their way through the legal system at this time.

State and Local Level

Each state is a little different, but in general, most states model their structure after the federal structure of government with a legislature, executive, and judiciary. In this section, I’ll summarize some of the key official actors in Minnesota; most other states have a similar structure.[15]

The Legislative Branch

The Minnesota legislature is like the federal system in that it is bicameral (has two chambers), but there are several important differences.[16] The state of Minnesota is divided into 67 legislative districts, each with about 80,000 residents. Each of these districts is represented by one Senator who is elected for a four year term, except once a decade (election years ending in 0) when they serve only a two year term. Each legislative district is divided in half (A and B) and each half elects a Representative. There are 134 Representatives (two in each Senate district) and Representatives serve two year terms. Legislators in Minnesota must be 21 years old and a resident of the state for at least a year. They have to live in the district for which they are running at least six months before the election. Minnesota’s legislature is a part-time institution, and so it only meets for a few months of the year, even though legislators are pretty busy all year long. Members get paid $31,140 per year and they also receive a daily stipend for living expenses when the legislature is in session (this is called a per diem allowance).

The current legislature is the most diverse in Minnesota history. Of the 201 elected legislators, 35 are people of color and 12 are part of the LGBTQ community. Five of the legislators who identify as people of color are Republicans, but the others are all part of the Democratic-Farmer-Labor party, Minnesota’s version of the Democratic Party. Another milestone in the 2022 election was that three Black women were elected to the Minnesota Senate, which is the first time that any Black woman has served in the Senate.

The Minnesota legislature also employs numerous staff members who work for individual members, the party caucuses, and committees. The role of Legislative Assistant is one of the main entry-level positions for people interested in working in politics and government. LAs work with assigned legislators to help with daily administrative tasks like scheduling, interacting with constituents, and tracking legislation.

Figure 2.5: Gustavus students at the Minnesota Capitol in March 2020. This building not only houses the legislative chambers (House and Senate), but it also houses the Governor’s office, and a ceremonial courtroom that was formerly used by the Minnesota Supreme Court.

The Executive Branch

Every U.S. state has an executive branch with an elected Governor who oversees the state bureaucratic agencies and functions as the chief spokesperson for the state. The power of governors varies across states, with some governors having full responsibility for setting the state’s budget and some having veto power over state legislative decisions. In addition to an elected governor, most states also have other statewide elected officials such as Lieutenant Governor and Attorney General.

Unlike the federal system, the Minnesota executive branch includes five executive offices who are elected statewide: The governor and lieutenant governor, the Secretary of State, the Auditor, and the Attorney General. The Governor and Lieutenant Governor are elected jointly for a four year term. The other three executive officers are elected individually, also for four year terms. The governor is the chief executive for the state, responsible for administering laws, appointing the heads of state departments and agencies, appointing judges to fill vacancies, proposing a budget, reviewing bills and either signing or vetoing them and serving as commander-in-chief of the state national guard. The lieutenant governor serves as an official representative of the governor and assumes the governor’s duties in the event that the governor is absent, incapacitated, or resigns. The secretary of state is the head election official in the state, certifies official state documents like laws, and regulates businesses in Minnesota. The auditor oversees audits of local governments in Minnesota, which means that they review the financial statements prepared by cities and counties to make sure they are accurate and complete. The attorney general is the primary lawyer for the state, providing legal advice to state agencies and representing the state in court cases.

Minnesota’s governor also has a cabinet, consisting of the leaders of the 24 cabinet departments. These individuals are called Commissioners and they are selected by the Governor and confirmed by the Senate. Minnesota also uses a civil service system for other agency employees. As at the federal level, people who work in state agencies are called bureaucrats.

Minnesota has never elected a non-white Governor, but the current lieutenant governor, Peggy Flanagan, is a member of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe (she is the first person of color to serve as lieutenant governor in Minnesota). It may or may not shock you to learn that across all 50 states over the entire history of the U.S., there have only been 27 governors who identify as people of color. Only 15 U.S. states have been represented by a governor who is not white (New Mexico leads the pack, having elected 7 governors of Mexican heritage).

The Judicial Branch

Each state also maintains its own state-level judicial system. State courts hear criminal cases and civil cases. Most court cases begin in state courts. States differ in terms of how they select judges for state courts. In some states, judges are appointed by governors or by the legislature. In other states, judges are elected through either partisan or nonpartisan elections.

Minnesota’s court system is structured similarly to the federal system. There are 87 district courts organized into 10 judicial districts, which are served by nearly 300 judges. Decisions can be appealed to the Court of Appeals, whose 20 or so judges hear cases as part of 3-judge panels. The final court of appeal is the Minnesota Supreme Court. There are 7 justices on the Supreme Court.

Judges in Minnesota are nonpartisan (not explicitly affiliated with a political party), elected to six-year terms, and must retire at age 70. When a vacancy occurs, the governor can fill the vacant position with a person recommended by the Minnesota Commission on Judicial Selection. Then, the judge or justice is up for reelection during the election cycle after they have served for one year. Anyone who meets the qualifications (“learned in the law” and admitted to practice law in Minnesota) can file to run in a judicial election, though the winning candidates are usually ones who have been appointed.

The demographics of state-level judges vary widely by state. In 20 states, there are no state supreme court justices who identify as a person of color. Among all state supreme courts, only 18% of justices are people of color and only 41% are women.[17]

Local Governments

Policy is also made at the local level–in counties, towns, townships, school districts, and other special districts. The U.S. Constitution doesn’t specifically mention local governments, but the 10th Amendment to the Constitution delegates powers not mentioned by the Constitution to the states and most states have delegated powers to lower levels of government.

In Minnesota, county governments play an important role in policymaking. There are 87 county governments, which are governed by 5-7 member elected county commissions, and other elected officials (sheriff, attorney, auditor, treasurer, etc.). County government elections are generally non-partisan. Cities may be ruled by a mayor and city council or just a city council and appointed city manager. City officials are also generally non-partisan. Other local government entities include school districts (overseen by an appointed superintendent and elected school board), soil and water conservation districts, and watershed districts, to name just a few.

Remember that the individuals and organizations I mentioned in this section aren’t always going to be official actors in every situation. I’ve described them in this section so that you are familiar with all the different actors, but we would only consider them to be official actors when they are dealing with an issue over which they have authority to act. If they are trying to influence policy in an arena where they don’t have authority to act, we would categorize them as unofficial actors.

2.2 Who are unofficial actors?

In addition to the many people who work in government positions, there are individuals and organizations that operate outside of the government structure to influence government decisions. These unofficial actors may not have the authority of law to make decisions, but they do a lot to shape the policies under consideration and sway the opinions of decision makers.

We’ve already discussed political parties in chapter one, but here I want to note that political parties operate as unofficial actors to shape policy outcomes. Parties generally outline their preferred policy outcomes through their party platforms, a list of their positions on major political issues. Party leaders attempt to influence which issues are under discussion by official actors and they try to hold their members to a common position on those issues. There are some demographic trends among people who identify as members of a political party. Women are slightly more likely to identify as Democrats (56%) than men (44%). 84% of Black voters, 63% of Hispanic voters, and 65% of Asian voters identify with the Democratic party.[18]

Interest groups, also known as advocacy groups, are another set of unofficial actors. Interest groups are organizations that engage in political activity. They are different from political parties because they don’t nominate candidates for office. They are different from social movements because they are more organized and structured. The primary goal of an interest group is to influence public policy in a way that is beneficial to members of the group. Interest groups include trade associations, labor unions, citizen groups, and professional associations. The advocacy efforts of for-profit businesses, non profit organizations, and colleges and universities also fall within this category. Lobbyists are the individuals who represent the interests of the group before government actors.

One of the most important ways that interest groups influence public policy is through providing decision makers with information. Interest groups serve as policy experts for decision makers who are forced through the demands of their job to be generalists. It’s just not possible for an elected official to know everything about every topic that comes before them. Interest groups work to develop a reputation for providing decision makers with accurate, up-to-date information. They also work to gain and maintain direct lines of communication with decision makers and their staff so that they will be able to share their perspectives on policy.

Research suggests that women are underrepresented in the lobbying profession. One study finds that women make up about 37% of lobbyists and are underrepresented in some of the biggest and most powerful lobbying firms.[19] Racial and ethnic minorities are underrepresented in the lobbying profession.[20]

Think tanks and research institutions conduct and disseminate research with the goal of influencing public policy. Most think tanks have an ideological affiliation. Research institutions are often affiliated with universities or governments, but they function similarly to think tanks (which are sometimes called “universities without students”). The Heritage Foundation is an example of a very influential conservative think tank. The Cato Institute is an influential libertarian think tank. The Brookings Institution is a think tank that has a reputation for being politically moderate. The Center for American Progress is a liberal think tank. Scholars affiliated with think tanks and universities play a major role in developing policy proposals and in evaluating the effectiveness of policies. Their research and ideas directly influence the decision making of official actors, particularly those who share their ideological positions.

The media plays an important role in the political process. The media includes traditional news outlets like newspapers, radio, and broadcast television as well as newer forms such as cable news, the internet, social media, and citizen journalists. Most journalists (the people who write the news stories) adhere to norms of objectivity and fairness in their reporting, but there are journalists and media outlets on both the right and the left of the ideological spectrum that seek to advance specific policy goals in their reporting. The political commentators featured in media outlets can also influence political outcomes through the arguments they advance. It is more challenging than ever for readers, listeners, and viewers to distinguish between political news and opinion. In the old days, a printed newspaper physically separated the news section from the opinion section. Today, all of those different articles pop up right next to each other in the news feed on your phone. Unless you look carefully at the fine print at the top of the article, you might not realize whether you’re reading news or commentary.

Figure 2.6: Tim Nelson ‘89, a reporter for Minnesota Public Radio, speaks with Gustavus students at the Day at the Capitol networking event in March 2020.

As I mentioned earlier, government actors can play a role as unofficial actors when they seek to influence policy outcomes over which they don’t exert control. Government officials can do this as individuals or as part of an organization, like the National Governors Association or the National Association of Chiefs of Police.

Finally, members of the public can operate as unofficial actors. Individuals do this any time they call, write, or email an elected official to advocate for an issue. With most public officials having a profile on social media, members of the public can even tag official actors in posts as a way of gaining their attention. Sometimes individuals are mobilized to action through other unofficial actors, particularly political parties and interest groups. One caveat to classifying members of the public as unofficial actors is when they act as policymakers during an initiative process (more about this in chapter 4).

2.3 Whose voices matter most?

One of the biggest questions facing scholars of public policy is whose voice matters the most when it comes to decision making. There are lots of ways of approaching this question, but there are two main schools of thought on the question: elite theory and pluralist theory.

Elite Theory

Some scholars and political observers argue that public policy outcomes reflect the preferences of political and economic elites and are not reflective of the needs or wants of average citizens. This perspective is termed Elite Theory and was developed by scholars such as C. Wright Mills, Thomas Dye, and William Domhoff.[21] Elite theory is an influential perspective for many policy scholars because it seems to help explain policy outcomes that conflict with public opinion.

One idea about public policy formation to emerge from the elite theory perspective is the concept of an iron triangle. An iron triangle is the closed relationship between a congressional committee or subcommittee, an executive agency, and powerful interest groups in a particular policy domain. The idea was that policymaking is controlled by different iron triangles that benefit from the stability of keeping the number of participants in a decision limited. The idea for focusing on small subsystems within government came from Ernest Griffith, who called them “whirlpools.”[22]

A variation of the iron triangle is the concept of a policy monopoly, developed by Frank Baumgarter and Bryan Jones. A policy monopoly refers to the small group of the most important actors (both official and unofficial) who control policy making in a given domain. But, unlike the iron triangle model, Baumgartner and Jones argue that policy monopolies can and do change regularly as policymakers and the public gain and lose interest in different topics. The policy monopoly concept recognizes that there are periods of stability in policymaking that come from having a small set of actors in control of decision making. However, it also recognizes that changes in the policy monopoly can lead to changes in policy as new actors come into the process and old ones are driven from it.

Pluralist Theory

Other scholars and political observers argue that policy outcomes are the result of a struggle between multiple groups within a society. For this camp, the competition between groups is a defining feature of political life. Public policy is a reflection of the interests and preferences of the winning groups. This perspective is termed Pluralism or Group Theory and was developed by scholars such as Earl Latham, David Truman, and Robert Dahl.[23] Group theory has also been an influential perspective for many policy scholars, especially in light of research which raised questions about the accuracy of the iron triangle model.[24]

One idea about public policy formation to emerge from the group theory perspective is the concept of issue networks, developed by Hugh Heclo.[25] An issue network is a loose constellation of participants who move in and out of the network at various points in the process. It might include official and unofficial actors

There is evidence to support and refute both elite theory and group theory, which means that there is no definitive answer to the question of whose voice matters the most. There are more actors involved in the policymaking process than elite theory suggests and yet the process is not an even playing field as group theory suggests. It is probably most accurate to say that there are times when elites dominate decision making and times when a broader range of participants influence outcomes.

E.E. Schattschneider offers some insight into when we might expect the number of participants to be limited and when we might expect it to be broad.[26] Schattschneider describes the scope of conflict in politics, arguing that those who are currently in position of power tend to prefer to privatize the conflict, limiting the number of participants in decision making. Keeping the decision making group small means that policy change is unlikely because the people in the room most likely already agree with the status quo, since they had a hand in setting it. In contrast, those who are unhappy with the status quo have an interest in socializing conflict, or expanding it to bring in new participants. As Schattschneider argues, “there is nothing intrinsically good or bad about any given scope of conflict. Whether a large conflict is better than a small conflict depends on what the conflict is about and what people want to accomplish.”[27]

2.4 Why should we care about actors?

In any given policy debate, the constellation of actors will vary, which can make things a little confusing. Learning to identify the key players in a policy debate is one of the most important steps in understanding the issue, especially if you want to influence the policy process. It just isn’t effective to write a persuasive letter to an actor who does not have an official role to play in a policy decision. Even if you are only trying to learn about a policy, it is important to identify which actors are trying to influence the decision and which actors have the authority to act on a decision. It can also be helpful to analyze the coalitions that form…which actors are aligned with which?

In addition to thinking about the roles themselves, it is also important to consider who the individual people are who occupy those roles. Life experiences matter. They shape our view and understanding of the world and, in turn, those views shape how people approach the creation of public policy. Policymaking is always going to reflect the views and experiences of policymakers, so it is worth taking the time to consider the lived experience of those policymakers.

Those individuals, in their role as official or unofficial policy actors, work hard to influence the policymaking process. Their influence involves both providing information and providing persuasive evidence in ways that are easily understandable and digestible by their audience, and this brings us back to thinking about writing.

2.5 What is an issue brief?

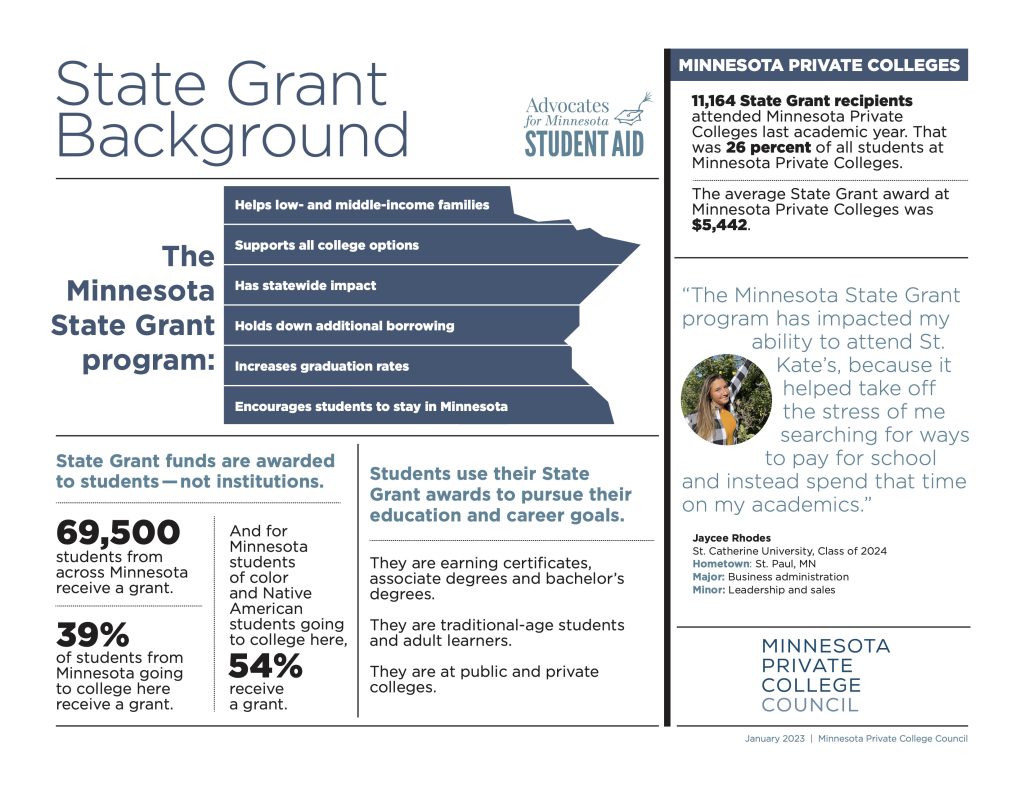

There are lots of ways that unofficial actors try to influence policy, but one common written technique, particularly among interest groups, is the issue brief. An issue brief is a very short document (1-2 pages) that is used to inform policymakers, and sometimes the public, about a particular issue. Sometimes this type of document might be called a fact sheet. If you ever attend a legislative hearing or participate in a day at the capitol event with an interest group, chances are that you will encounter an issue brief.

The purpose of an issue brief is both to inform and persuade an audience. The primary audience for an issue brief are decision makers like legislators.

Writing an issue brief requires knowing a lot about an issue but then being able to communicate the most important information clearly and concisely, which is why I like to say that an issue brief is a research-based document written for busy people. There are a few distinguishing features of an issue brief.

First, it is brief. 1-2 pages maximum. Because it’s so short, it usually focuses on a very narrow aspect of the policy.

Second, it is written for a general audience rather than a specific person. Ultimately, the goal is to provide decision makers with information, but an issue brief is not targeted to a specific individual legislator. As a result, issue briefs need to clearly summarize any information that isn’t common knowledge and need to use language that is accessible to people who aren’t experts in the topic.

Third, issue briefs focus on communicating the facts about the issue. Although the goal is ultimately always persuasion, writers of issue briefs don’t want to be viewed as partisan hacks. They want to present unbiased, nonpartisan information in a way that demonstrates the validity of their position. Decision makers need quality information, and producers of issue briefs want to provide them with that and to maintain their credibility as a high quality source of information.

Fourth, issue briefs often incorporate elements of graphic design, like infographics, pictures, figures, and bulleted lists to communicate information quickly and effectively. The layout of an issue brief should be visually appealing and easy to read.

Issue briefs are produced by advocacy groups to distribute to legislators during legislative advocacy days or posted on the group’s website to serve as a resource for the media, legislative staffers, or group members.

AI can offer some help when it comes to writing issue briefs. AI could be used to generate ideas about what information to include in an issue brief, but you need to look at what it produces carefully to ensure that it hasn’t hallucinated information. If you are producing an issue brief for an advocacy group, that group’s name and reputation are on the line and so accuracy is crucial. Another consideration is that AI writing tends to be verbose and generic, so you may have to do quite a bit of editing to make sure it clearly communicates your message. There are lots of AI-based tools that can help with graphic design or creating infographics. Piktochart and Canva are two programs that can be used to produce visually appealing issue briefs.

Take a look at this sample issue brief. Can you spot the stylistic markers that make it an issue brief? Who issued it? What purpose do they have for writing it? How do they use elements of graphic design to support their message?

Figure 2.7: Sample issue brief from the Minnesota Private College Council about the Minnesota State Grant Program.

Closely related to issue briefs are bill summaries. A bill summary is quite literally a summary of the contents of a specific bill. Like issue briefs, a bill summary must be very short, accessible to a general audience, and unbiased. Unlike issue briefs, they are generally fairly text heavy rather than relying on graphics and images. Bill summaries are usually written by legislative staffers rather than interest groups. The primary audience for a bill summary is legislators, but interested members of the public might also read them. There’s an example of a bill summary in the next section.

2.6 Why do you write?

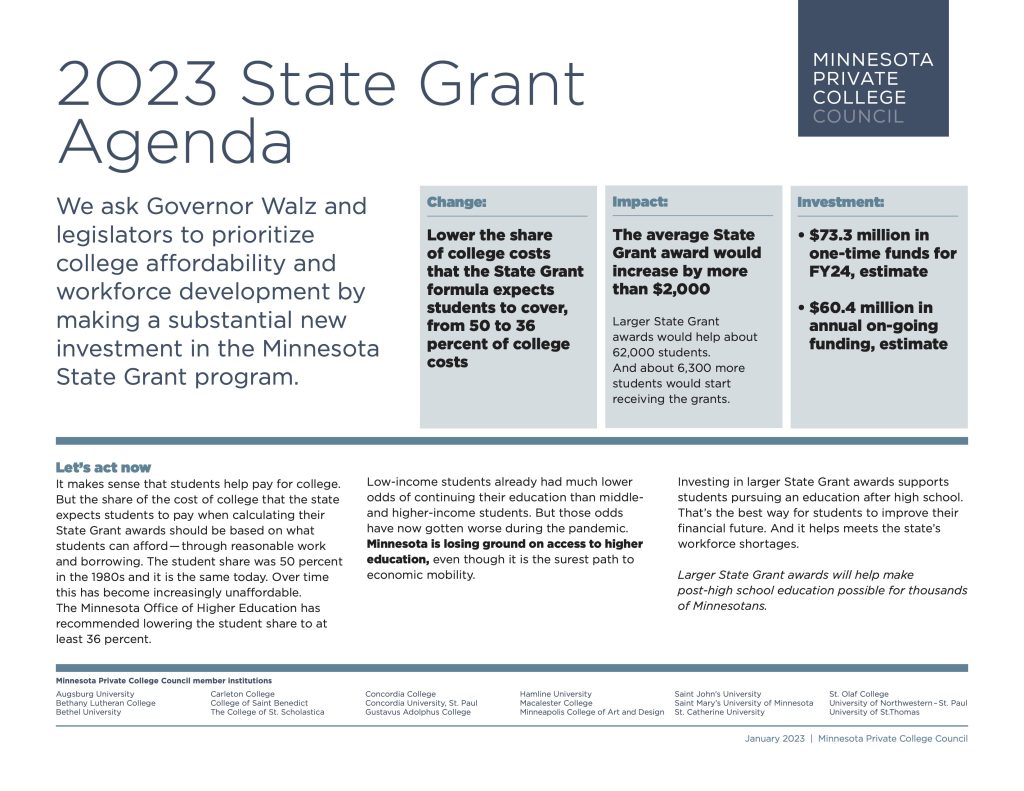

Figure 2.8: Jessye Flannery ‘13, Research Analyst for the Iowa House of Representatives Democratic Research Staff in the Iowa House of Representatives chambers

I was born and raised in Des Moines, Iowa. Growing up my parents frequently talked about politics at the dinner table, and I had a few distant relatives who were elected officials. From a very young age I was interested in politics. In seventh grade I job-shadowed the chief clerk of the Iowa House of Representatives and fell in love with the political process. That led me to become a legislative page my junior year of high school which only solidified my passion for politics. When picking a college, I knew I was going to major in political science and ultimately chose Gustavus because they had a larger political science program than the other schools I considered.

After graduating from Gustavus, I moved back to Des Moines where I was a legislative clerk in the Iowa House. I managed an Iowa House race in 2014 and then worked for an interest group for the 2016 Iowa caucuses and general election. While campaigns were not my ultimate goal in politics, it was necessary to make the connections to move up in the political world. Now I am a research analyst with the House Democratic Research Office with the Iowa House of Representatives. My office provides support to all Democratic Representatives. I staff the Agriculture, Economic Growth, Labor, Transportation, and Economic Development Budget Committees. I am responsible for going to all committee and subcommittee meetings, reading all the bills voted on, and doing bill summaries for my committees. Helping Representatives respond to constituent questions is also a large part of my job, even when the legislature is not in session.

My position requires me to write every day. I write bill summaries, research briefs on different policy topics, longer issue backgrounders, newsletter articles, and constituent correspondence. Most of my writing requires research. I consult Iowa Code, legislative liaisons for departments within the state, online resources, and my coworkers. My writings usually go to the Representatives I staff. My bill summaries also go to the press and some lobbyists. Newsletter articles and constituent correspondence go to constituents. Representatives will send on the other reports I do to interested constituents. Everything I write, I write with the understanding it is public.

With the exception of constituent correspondence, everything I write has a predetermined template. I fill in the information and research in the template. This makes reports coming from anyone in my office uniform. I also build on past reports, some of which were not written by me. I update information that was previously written and add any changes in policy. The topics of the reports I write are determined by other people and usually based on popular policy topics. All formal reports are proofread by others. After the first proof is when most of the editing takes place. Writing has become easier with my growing understanding of the topic areas I staff.

During the session I get to work early to write bill summaries. I get more done between 7 and 8 in the morning than I do the rest of the day. I try to work on things in between committee meetings and floor debate but I usually get interrupted and finish at night after most people have gone home.

Over the years in my job, I have learned to write differently depending on what I am writing and who the audience is. When I write a bill summary, I summarize the entire bill, give background information as needed, and I do not need to be concise. When I write a newsletter article for Representatives to send to constituents, I need to be concise. This means I do not need to include all the details of the bill or policy but instead focus on how the policy will impact lives. Being concise and not giving all the details is something I continue to work on. I find writing out everything I want to say and then pairing down the details works best for me.

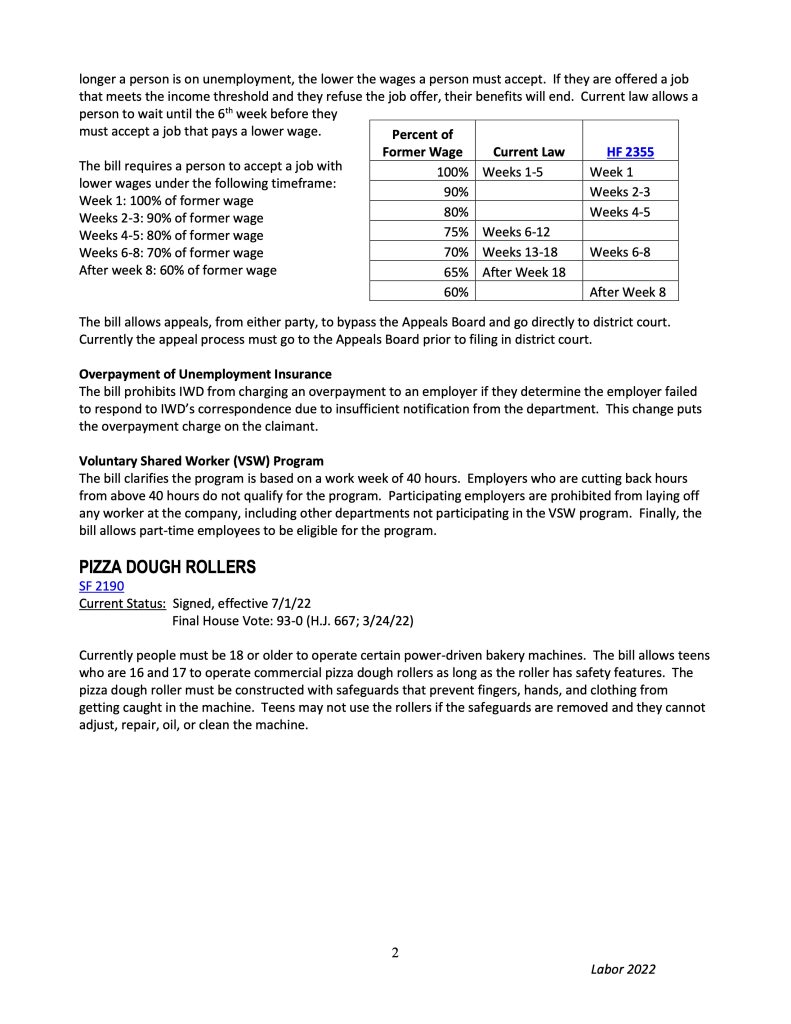

After the legislative session concludes, my office writes summaries for every bill passed out of committee. My writing sample is an excerpt from my end of session summaries for bills passed by the Labor Committee. HF 2355 was one of the most controversial bills that became law during the 2022 legislative session. SF 2190 was a much simpler bill that passed with unanimous support. These end of session summaries are sent to all Representatives to use back in their districts. Staffers in my office, myself included, often refer to previous end of session summaries to answer questions.

Figure 2.9: Bill summary sample written by Jessye Flannery

2.7 What comes next?

In this chapter, we focused on identifying the main players in the policymaking process. These players come both from inside and outside government, but they all play a role in influencing policy outcomes. Identifying the key actors in a given situation is an important first step in analyzing policy. From there, we can consider questions about which actors have the most policy influence and why.

In the next chapter, we explore the question of timing…why is it that we talk about certain issues at certain times but not at others? We’ll build on what we know about policy actors to consider how they act to bring items to the attention of decision makers or push them out of the public eye.

Questions for discussion

- What official actors have you interacted with in your life? What was the context for your interaction with them?

- Are your viewpoints represented by any unofficial actors? For example, are you part of a political party or interest group? Have you ever participated in political advocacy (writing or calling a legislator, attending a day at the Capitol lobbying event, participating in a march or protest, etc.)?

- Why might it be important to consider the demographic characteristics of the actors who influence policy making? What other demographic characteristics might matter beyond those discussed in this chapter?

- What questions does the material in this chapter raise for you about public policy, the policymaking process, or writing about public policy?

Glossary

Appellate Courts: Courts that review the decisions of the lower, district courts. There are 13 appellate courts in the federal system staffed by 170 judges.

Attorney General (State): the primary lawyer for the state, providing legal advice to state agencies and representing the state in court cases.

Bureaucrats: People who work for government agencies in the executive branch.

Cabinet: Composed of the Vice President and the leaders of the main executive branch departments. It serves an advisory role only and does not have the power or authority to make decisions on its own.

Civil Service System: A merit-based system in which most federal jobs (about 90%) require a person to have expertise in the topic and be qualified to hold the position and it also means that most federal bureaucrats hold the job regardless of the president in power and they are protected from being fired for political reasons.

Commissioners: The leaders of 24 cabinet departments of Minnesota’s governor’s cabinet. They are selected by the Governor and confirmed by the State Senate.

Confirmation: Congressional approval of positions within the executive and judicial branch.

District Courts: The first level of the federal court system, where most cases originate. There are 94 district courts staffed by 673 district court judges. These are the courts that hold trials with evidence presented and witnesses who testify.

Elite Theory: This theory argues that public policy outcomes reflect the preferences of political and economic elites and are not reflective of the needs or wants of average citizens. Keep in mind that this is a theory designed to explain observed reality; it is not a normative argument in favor of elite control over government.

Executive Departments: The fifteen major administrative units in government including Agriculture; Commerce; Defense; Education; Energy; Health and Human Services; Homeland Security; Housing and Urban Development; Justice; Labor; State; Interior; Treasury; Transportation; and Veterans Affairs.

Executive Office of the President: Created in 1939 to provide the President with expert advisors. It includes the people who work directly in the White House Office as well as those in the Office of Management and Budget, the national Economic Council, the Domestic Policy Council, the National Security Council, and other organizations.

Federalism: A system in which powers are split between two or more levels of government.

Governor: the chief executive for the state, responsible for administering laws, appointing the heads of state departments and agencies, appointing judges to fill vacancies, proposing a budget, reviewing bills and either signing or vetoing them and serving as commander-in-chief of the state national guard.

Government Corporations: Also known as businesses established by Congress that perform some type of public service that could theoretically be performed by a private business.

Independent Agencies: Oversee specific government operations such as elections (the Federal Election Commission) or space exploration (NASA).

Independent Regulatory Agencies: Oversee specific economic activities such as the Securities and Exchange Commission or the Consumer Product Safety Commission).

Interest Groups: Also known as advocacy groups, are another set of unofficial actors. Interest groups are organizations that engage in political activity.

Iron Triangle: The closed relationship between a congressional committee or subcommittee, an executive agency, and powerful interest groups in a particular policy domain.

Issue Brief: A very short document (1-2 pages) that is used to inform policymakers, and sometimes the public, about a particular issue.

Issue Network: A loose constellation of participants who are working to influence a particular policy area.

Journalists: The people who write news stories.

Judge: Federal judges are nominated by the President and confirmed by a majority vote of the U.S. Senate to serve at the district and appellate levels.

Justice: Nominated by the President and confirmed by a majority vote of the U.S. Senate to serve at the Supreme Court; the leader of the Supreme Court is called the Chief Justice.

Legislate: Congress proposes, debates, and passes (or fails to pass) bills that create and fund public policies.

Lieutenant governor: serves as an official representative of the governor and assumes the governor’s duties in the event that the governor is absent, incapacitated, or resigns.

Lobbyists: The individuals who represent the interests of a business or interest group before government actors.

Members of Congress: The 100 elected Senators (two from each state) serving in the U.S. Senate and 435 elected Representatives (based on population) serving in the House of Representatives.

Media: Plays an important role in the political process. The media includes traditional news outlets like newspapers, radio, and broadcast television as well as newer forms such as cable news, the internet, and social media.

Minnesota Legislature: The branch of state government responsible for proposing, debating, and passing legislation. Like the federal system, the Minnesota legislature is bicameral (has two chambers), but there are several other important differences.

Nonpartisan: People not explicitly affiliated with a political party.

Official Actors: Actors that have an authorized role to play in the policymaking process based on the Constitution or statute (law).

Office of Management and Budget: A particularly important office within the executive branch that is responsible for preparing the president’s annual budget proposal and reviewing all proposed bills and agency regulations.

Oversight: Congress’ power to provide checks and balances on other branches of government by holding hearings, calling officials to testify in front of Congress, and issuing written reports about government agencies.

Party Platforms: A list of a party’s positions on major political issues where they outline their preferred policy outcomes.

Policy Monopoly: The small group of the most important actors (both official and unofficial) who control policy making in a given domain.

Pluralism or Group Theory: A theory that argues that the creation of public policy involves a struggle between different groups within society and the resulting policy reflects the interests and preferences of the winning groups.

President: The chief executive within the U.S. federal government. Presidents are responsible for overseeing the implementation of public policy and reviewing (by signing or vetoing) laws passed by Congress.

Representatives: Serve in the House of Representatives from geographical districts and are elected to two year terms.

Representation: This is the extent to which Congress reflects the voices and viewpoint of the people in the decision making process.

Scope of Conflict: This refers to the number of people involved in a particular decision. Those who are currently in a position of power tend to prefer to privatize the conflict, limiting the number of participants in decision making.

Secretary: The people who lead each of the departments within the executive departments. They are nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, but they serve at the pleasure of the President. All of the federal cabinet-level departments are led by a Secretary with the exception of the Department of Justice, which is led by the Attorney General.

Secretary of state: The Secretary of State is the head election official in the state, certifies official state documents like laws, and regulates businesses in Minnesota.

Senators: Serve in the Senate and are elected to six year terms; one third of the Senate is up for election in even years. (In Minnesota, Senators are elected to four year terms.)

Separation of Powers: At each level of government (federal, state, and local), power is further split between different branches of government (legislative, executive, and judicial).

State Auditor: The state auditor oversees audits of local governments in Minnesota, which means that they review the financial statements prepared by cities and counties to make sure they are accurate and complete.

Think Tanks: Research institutions that conduct and disseminate research with the goal of influencing public policy. These are often described as universities without students.

Unofficial Actors: Actors that have an interest in policy outcomes and work hard to influence policy outcomes, but lack the legal standing to actually make a policy decision.

U.S. Supreme Court: The highest level of court in the federal system, staffed by 9 justices.

Venues: Centers of policy making power.

Additional Resources

U.S. House of Representatives: https://www.house.gov/

U.S. Senate: https://www.senate.gov/

Track federal legislation: https://www.congress.gov/

The White House: https://www.whitehouse.gov/

Data about presidents: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/

The Supreme Court: https://www.supremecourt.gov/

Information about Supreme Court cases: https://www.oyez.org/

The Minnesota Legislature: https://www.leg.mn.gov/

The Minnesota Governor: https://mn.gov/governor/

The Minnesota Judicial branch: https://www.mncourts.gov/

The New York Times (subscription available for free to Gustavus students): https://www.nytimes.com/

The Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/

National Public Radio (free): https://www.npr.org/

Minnesota Public Radio (free): https://www.mprnews.org/

The Minnesota Star Tribune (subscription available for free to Gustavus students): https://www.startribune.com/

The Minnesota Reformer (free): https://minnesotareformer.com/

MinnPost (free): https://www.minnpost.com/

The Democratic Party: https://democrats.org/

The Republican Party: https://www.gop.com/

Thanks for reading this chapter. The book in which this chapter sits is a work in progress and I welcome feedback and suggestions for improvement. If you notice incorrect or out of date information, please let me know using the feedback form linked below. If something was particularly helpful to you, I’d also love to hear about it. If you are a faculty member or public policy practitioner who is interested in collaborating on this project, you can also use this feedback form to contact me. ~Kate

Feedback form: https://forms.gle/LKBykHHRLe2kNW2AA

- Katherine Schaeffer, “U.S. Congress Continues to Grow in Racial, Ethnic Diversity,” Pew Research Center, January 9, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/10/the-changing-face-of-congress/ ↵

- Aline Barros, “Upcoming US Congress Likely to Keep Its Share of Foreign-Born Lawmakers,” Voice of America, November 19, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/upcoming-congress-likely-to-keep-its-share-of-foreign-born-lawmakers/6838199.html ↵

- Rebecca Leppert and Drew DeSilver, “118th Congress Has a Record Number of Women,” Pew Research Center, January 4, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2023/01/03/118th-congress-has-a-record-number-of-women/. ↵

- Rebecca Leppert and Drew DeSilver, “118th Congress Has a Record Number of Women,” Pew Research Center January 4, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2023/01/03/118th-congress-has-a-record-number-of-women/. ↵

- Katherine Schaeffer, “118th Congress Breaks Record for Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Representation,” Pew Research Center, January 11, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2023/01/11/118th-congress-breaks-record-for-lesbian-gay-and-bisexual-representation/ ↵

- “Diversity Among U.S. Senate Democratic Staff on June 30th, 2021,” Diversity Among U.S. Senate Democratic Staff on June 30th, 2021 https://www.democrats.senate.gov/about-senate-dems/diversity-initiative/democratic-staff-survey-results-2021 ↵

- Lashonda Brenson, “Racial Diversity Among Senate Committee Top Staff,” Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, July 22, 2021. https://jointcenter.org/racial-diversity-among-senate-committee-top-staff/ ↵

- Casey Burgat, “Among House Staff, Women Are Well Represented. Just Not in the Senior Positions,” The Washington Post, June 20, 2017. ↵

- Curtis was a Republican from Kansas who served with President Herbert Hoover. He was a member of the Kaw Nation. He supported an assimilation policy, which pushed Native Americans to adopt western ways in exchange for being granted citizenship. ↵

- Alana Wise, “Biden Pledged Historic Cabinet Diversity. Here’s How His Nominees Stack Up,” NPR, February 5, 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/president-biden-takes-office/2021/02/05/963837953/biden-pledged-historic-cabinet-diversity-heres-how-his-nominees-stack-up ↵

- Office of Federal Operations. Annual Report on the Federal Workforce. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. https://www.eeoc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-06/2018 Federal Sector Report.pdf ↵

- J. Edward Kellough, “Integration in the Public Workplace: Determinants of Minority and Female Employment in Federal Agencies,” Public Administration Review 50, no. 5 (September 1, 1990, 557-566); Sungjoo Choi, “Diversity and Representation in the U.S. Federal Government: Analysis of the Trends of Federal Employment,” Public Personnel Management 40, No. 1 (Spring 2011, 25-46). ↵

- “January 20, 2021 Snapshot: Diversity of the Federal Bench.” American Constitution Society. Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.acslaw.org/judicial-nominations/january-20-2021-snapshot-diversity-of-the-federal-bench/ ↵

- Russell Wheeler, “Biden’s First-Year Judicial Appointments--Impact,” Brookings Institution, January 27, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2022/01/27/bidens-first-year-judicial-appointments-impact/ ↵

- One big exception is Nebraska, which has the only unicameral legislature in the country. ↵

- Legislature refers to the institution. Legislator refers to the individuals who serve in the legislature. Legislation refers to the bills and laws that are sponsored by legislators and approved through the legislature. ↵

- Amanda Powers and Alecia Bannon, “State Supreme Court Diversity--May 2022 Update,” Brennan Center for Justice, May 25, 2022. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/state-supreme-court-diversity-may-2022-update ↵

- “Wide Gender Gap, Growing Educational Divide in Voters’ Party Identification,” Pew Research Center, March 2018, 7 https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2018/03/20/1-trends-in-party-affiliation-among-demographic-groups/ ↵

- Timothy M. LaPira, Kathleen Marchetti, and Herschel Thomas, “Gender Politics in the Lobbying Profession,” Politics & Gender 10, no. 3 (2020): 816-844. ↵

- “Diversity and Inclusion In Government Relations Survey,” Diversity in Government Relations Coalition, Accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.dgrcoalition.org/our-survey ↵

- C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956); Thomas Dye, Top Down Policymaking (New York: Chatham House, 2001); William Domhoff, Who Rules America: Challenge to Corporate and Class Dominance, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2009). ↵

- Ernest Griffith, The Impasse of Democracy, (New York: Harrison-Hilton Books, 1938), 182. ↵

- Earl Latham, The Group Basis of Politics (New York: Octagon Books, 1965); David Truman, The Governmental Process (New York: Knopf, 1951); Robert Dahl, Democracy and Its Critics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989). ↵

- Hugh Heclo, “Issue Networks and the Executive Establishment,” in Anthony King, ed., The New American Political System (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute, 1978), 87-124. ↵

- Hugh Heclo, “Issue Networks and the Executive Establishment,” in Anthony King, ed., The New American Political System (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute, 1978), 87-124. ↵

- E. E. Schattschneider, The Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1960). ↵

- E. E. Schattschneider, The Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1960), 17. ↵

Actors that have an authorized role to play in the policymaking process based on the Constitution or statute (law).

Actors that have an interest in policy outcomes and work hard to influence policy outcomes, but lack the legal standing to actually make a policy decision.

A system in which powers are split between two or more levels of government.

At each level of government (federal, state, and local), power is further split between different branches of government (legislative, executive, and judicial).

Centers of policy making power.

The 100 elected Senators (two from each state) serving in the U.S. Senate and 435 elected Representatives (based on population) serving in the House of Representatives.

Serve in the Senate and are elected to six year terms; one third of the Senate is up for election in even years. (In Minnesota, Senators are elected to four year terms.)

Serve in the House of Representatives from geographical districts and are elected to two year terms.

Congress proposes, debates, and passes (or fails to pass) bills that create and fund public policies.

Congressional approval of positions within the executive and judicial branch.

Congress’ power to provide checks and balances on other branches of government by holding hearings, calling officials to testify in front of Congress, and issuing written reports about government agencies.

This is the extent to which Congress reflects the voices and viewpoint of the people in the decision making process.

The chief executive within the U.S. federal government. Presidents are responsible for overseeing the implementation of public policy and reviewing (by signing or vetoing) laws passed by Congress.

Created in 1939 to provide the President with expert advisors. It includes the people who work directly in the White House Office as well as those in the Office of Management and Budget, the national Economic Council, the Domestic Policy Council, the National Security Council, and other organizations.

A particularly important office within the executive branch that is responsible for preparing the president’s annual budget proposal and reviewing all proposed bills and agency regulations.

Composed of the Vice President and the leaders of the main executive branch departments. It serves an advisory role only and does not have the power or authority to make decisions on its own.

The fifteen major administrative units in government including Agriculture; Commerce; Defense; Education; Energy; Health and Human Services; Homeland Security; Housing and Urban Development; Justice; Labor; State; Interior; Treasury; Transportation; and Veterans Affairs.

The people who lead each of the departments within the executive departments. They are nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, but they serve at the pleasure of the President. All of the federal cabinet-level departments are led by a Secretary with the exception of the Department of Justice, which is led by the Attorney General.

Oversee specific government operations such as elections (the Federal Election Commission) or space exploration (NASA).

Oversee specific economic activities such as the Securities and Exchange Commission or the Consumer Product Safety Commission).

Also known as businesses established by Congress that perform some type of public service that could theoretically be performed by a private business.

People who work for government agencies in the executive branch.

A merit-based system in which most federal jobs (about 90%) require a person to have expertise in the topic and be qualified to hold the position and it also means that most federal bureaucrats hold the job regardless of the president in power and they are protected from being fired for political reasons.

The first level of the federal court system, where most cases originate. There are 94 district courts staffed by 673 district court judges. These are the courts that hold trials with evidence presented and witnesses who testify.

Courts that review the decisions of the lower, district courts. There are 13 appellate courts in the federal system staffed by 170 judges.

The highest level of court in the federal system, staffed by 9 justices.

Members of the judicial branch who make decisions about court cases.

Members of the judicial system who serve on the U.S. Supreme Court

Leader of the U.S. Supreme Court.

The branch of state government responsible for proposing, debating, and passing legislation. Like the federal system, the Minnesota legislature is bicameral (has two chambers), but there are several other important differences.

the chief executive for the state, responsible for administering laws, appointing the heads of state departments and agencies, appointing judges to fill vacancies, proposing a budget, reviewing bills and either signing or vetoing them and serving as commander-in-chief of the state national guard.

serves as an official representative of the governor and assumes the governor’s duties in the event that the governor is absent, incapacitated, or resigns.

The Secretary of State is the head election official in the state, certifies official state documents like laws, and regulates businesses in Minnesota.

This elected position oversees audits of local governments in Minnesota, which means that they review the financial statements prepared by cities and counties to make sure they are accurate and complete.

the primary lawyer for the state, providing legal advice to state agencies and representing the state in court cases.

The leaders of 24 cabinet departments of Minnesota's governor’s cabinet. They are selected by the Governor and confirmed by the State Senate.

Court cases that involve violations of the law. In these cases, the government acts to prosecute the alleged perpetrator.

Civil cases involve disputes between two private individuals or entities.

People not explicitly affiliated with a political party.

A list of a party’s positions on major political issues where they outline their preferred policy outcomes.

Also known as advocacy groups, are another set of unofficial actors. Interest groups are organizations that engage in political activity.

The individuals who represent the interests of a business or interest group before government actors.

Research institutions that conduct and disseminate research with the goal of influencing public policy. These are often described as universities without students.

Plays an important role in the political process. The media includes traditional news outlets like newspapers, radio, and broadcast television as well as newer forms such as cable news, the internet, and social media.

The people who write news stories.

This theory argues that public policy outcomes reflect the preferences of political and economic elites and are not reflective of the needs or wants of average citizens. Keep in mind that this is a theory designed to explain observed reality; it is not a normative argument in favor of elite control over government.