1 What is Public Policy?

Katherine Knutson and Henry Adebisi

Wondering why some text is in blue? Click here for more information.

1.0 Why did I write this book?

This morning I listened to news from NPR, a station born of the 1967 Public Broadcasting Act. As I ate breakfast, I read the government-mandated nutrition label on the box of cereal. I left the house for work using a road maintained by taxes. The regulations that guided my hiring and employment, the programs that protect me from poverty and sickness, the laws that ensure I have access to clean air to breathe and water to drink, are just some of the many ways in which government policies impact my life on a daily basis.

Unfortunately, not everyone in the United States has experienced public policies in this way. The residents of Flint, Michigan, were exposed to toxic levels of lead in their drinking water supply over a multi-year period as a result of government decisions that failed to prioritize the health and wellbeing of the community. Similarly, years after over 600,000 young undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children were given legal protection to work and attend school without fear of deportation through an Executive Order, these Dreamers (as they are called in reference to a policy proposal called the DREAM Act) are still living in legal limbo, without a permanent path to citizenship or access to many educational and employment benefits. What these examples suggest is that, whether for benefit or for harm, public policies directly impact the daily lives of people living in the United States.

Knowing the impact policy has on our lives leads me to many questions. How do policies that affect our lives so dramatically come into existence? What factors affect the decisions that government officials make? Why do we have this set of policies rather than something else? Why don’t we pass some policies that are very popular but do pass some policies that aren’t popular? Why do the policies that we have benefit some at the expense of others?

This book is an introduction to the study of U.S. Public Policy designed to address these questions. It was written for Gustavus students, by a Gustavus professor, and with contributions from Gustavus alumni. Because I had this audience in mind while writing the book, many of the examples are specific to the experience of Gustavus students and I’ve marked these with blue text. If you’re not a Gustavus student, you are welcome to skip these chunks without missing any of the main ideas.

This book is intended for those with some familiarity with the U.S. political system who want to learn more about the policies that govern our lives, want to understand why our policies look the way they do, and want to be able to analyze both policies and the policymaking process in a way that moves beyond the partisan rhetoric that characterizes contemporary politics.

I wrote this book after teaching U.S. Public Policy at Gustavus for 17 years. Over the years, I’ve used four different textbooks, each with various strengths and weaknesses. I’ve also witnessed the price of textbooks increase and the impact those extra costs have on students. I wrote this book for two primary reasons. First, I want to provide a free resource to my students so that everyone in the class has full access to the course material. Second, I want to present the material through themes that are not represented in any of the other existing textbooks on the subject.

Figure 1.1: My daughter takes one of the public policy textbooks I’ve used in this class for a walk in the Sohre Hall apartment, circa 2014.

This text explores the topic through two themes that permeate the book. First, I emphasize the impact of race, class, and gender on the formation and implementation of public policy. This approach is rooted in the theoretical framework, the Social Construction of Target Populations, first articulated by Anne Schneider and Helen Ingram in 1993, and described in more detail in chapter 5.[1] This theory calls our attention to the ways in which both political power and social constructions interact to produce policy outcomes and how these outcomes feed messages back to individuals about the political process and their value in the democratic process.

Second, I emphasize the importance and skill of writing in the field of public policy. Each chapter introduces students to a different genre common in the field and features reflections and writings from Gustavus alumni who work in a variety of public policy-related careers. Rather than thinking of writing as a separate process from learning about policy and policymaking, I hope that students will use writing as a way to learn about policy and policymaking and will develop practical skills to become better writers. I’ve found that most Gustavus students are very good at writing term papers; however, writing in public policy-related careers requires a different skill set…the ability to find and analyze different types of material, to synthesize information clearly and concisely, and to differentiate situations that call for an informative approach from situations that call for a persuasive approach, and respond accordingly.

I’m aiming for short, accessible chapters that summarize the most important concepts and theories, supplemented by sidebars that highlight contributions from Gustavus alumni. I’ll provide resources for learning more information about some of the topics, for those who want to dig a little deeper. Each chapter is guided by a key question. I find that defining research questions is an important part of my research process, and I encourage students to formulate their own research questions as we move through this material.

1.1 What is public policy?

With that said, let’s jump into the study of U.S. public policy and policymaking! Your first question might be: what is public policy? There are dozens of definitions, but the one I prefer combines aspects of definitions from both Carter Wilson and Thomas Dye: public policy is the authoritative statements and actions of the government that reflect what governments choose to do or not to do.”[2] Policymaking involves the processes for how governments do this and why they make the particular decisions they do. Or, to put it another way, public policy is the “what?” and policymaking is the “why?” and “how?”. These definitions give us space to talk about existing policies (or proposals) and to think about how they came into being (or why they failed to come into being) and what impact they have. Although lots of organizations make and have policies, in this book, we are especially interested in the policymaking activity of domestic government institutions. Domestic means that this book is focused on the policies and policy proposals that affect things within the United States rather than in foreign policy or the policies of other nation states. Government includes the institutions operating at the national (federal), state, and local level. And institutions include any of the bodies that are designed to formulate and implement public policy including legislatures, executives, bureaucratic agencies, and courts. Some of the individuals working in these institutions are elected, some are appointed, and some are hired based on their expertise or ability.

There are lots of ways we could approach the study of public policy. In this book, I will introduce you to some of the main theoretical approaches scholars of public policy have developed to make sense of public policy. The theories are meant to both explain what has happened in the past and to help us make predictions for future policymaking. Theories will never be able to explain all of an outcome and they usually won’t allow us to make completely accurate predictions, but they do help call our attention to the important aspects of the policymaking process. We will also learn some of the key terms (concepts) that are common in the field. I’ll bold any key concepts that you should know so that it is easy to find these important ideas. These terms are the vocabulary building blocks of the study of public policy and so it is important to understand what they mean and how to use them. In the first half of the book, I focus on big questions that help us understand the policymaking players and process. In the second half of the book, we dive into a few specific public policies, using the guiding questions from the first half to explore the policies in more depth.

1.2 Is there a pattern to public policy?

One way we could approach the study of public policy is by picking out a few policies that are interesting and learning more about them, but this would be pretty unsatisfying from the perspective of a social scientist. Social scientists want to be able to find commonalities between different topics and explain processes in addition to describing what we see. Social scientists who study public policy have taken a lot of different approaches ranging from developing frameworks or typologies that are fairly simple to developing very complex theories. In this section, I’ll introduce you to two foundational frameworks and one typology that have been very influential in the study of public policy. In subsequent chapters, I’ll introduce you to a few more complex theories that help to explain the policymaking process. The purpose of a theory is to provide us with an outline of how a process works and to call our attention to certain key aspects of the process. Theories offer a simplified version of the process rather than describing every detail of the process. You’ll notice that the different theories described in this book attempt to explain and call our attention to different aspects of the process. Ideally, a theory will offer some predictive power that will help us to make an educated guess about a future situation, but even when it doesn’t, a theory can still be useful because it gives us the tools to analyze a policy or policy process by drawing attention to the aspects and processes that are important.

Political Systems Model

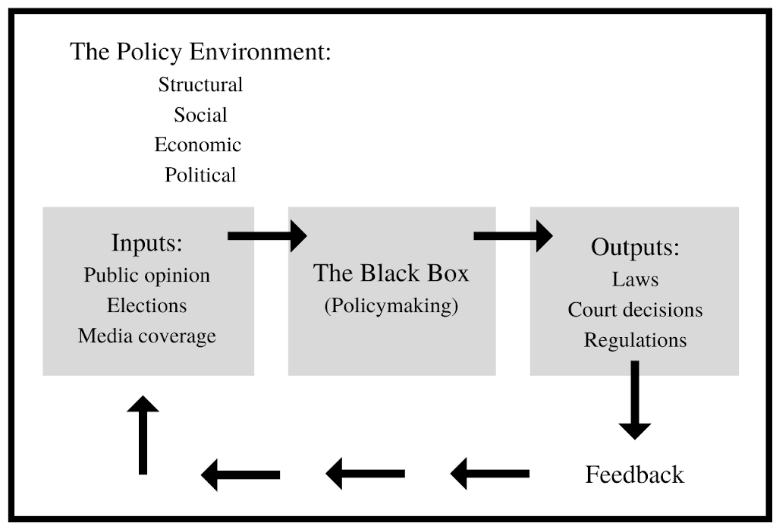

One of the earliest attempts to make sense of the policymaking process comes from David Easton.[3] In a 1957 article and a 1965 book, Easton attempted to provide a broad framework for understanding how decisions are enacted in society. Easton’s Political Systems Model conceived the process as involving inputs and outputs into a political system embedded within an environment. Inputs include demands for action that come from individuals and groups as well as the support for the system that comes when individuals and groups accept the system of government, for example by paying taxes, obeying laws, and abiding by results of elections. The outputs of the political system are the policies such as laws, court decisions, and bureaucratic regulations. These outputs feed back into the political system, in a process appropriately called feedback.

Figure 1.2: The Political Systems Model

This process happens within a specific context, and Easton calls us to pay attention to four components of this context, what he terms “the policy environment.” First, he points us to the political environment, which includes factors such as which political party controls the government, approval ratings of politicians, the public mood, and voter turnout in elections. Second, is the economic environment. This includes the distribution of wealth and indicators of economic health such as unemployment, wages, and the gross domestic product. Third is the social environment. This includes the composition of the population according to factors such as age, race, gender, and immigration status. Finally is the structural environment. This includes the constraints placed on policymaking as the result of federalism and the separation of powers.

According to the Political Systems model, the outputs produced by the policymaking system provide feedback that then influences the next set of decisions.

The Political Systems model is useful because it calls our attention to the overall policy process and to key factors that we should consider in analyzing politics. It is definitely important to consider the policy environment and the inputs that shape policy outputs. It is also useful to think about the many different types of policy outputs, including laws, court decisions, and regulations. Easton also helps us remember that the policies themselves affect the creation of new policies (feedback). However, Easton’s model raises more questions than it answers. For example, what exactly happens in that “political systems” box? Do all aspects of the environment matter equally?

Lowi Typology

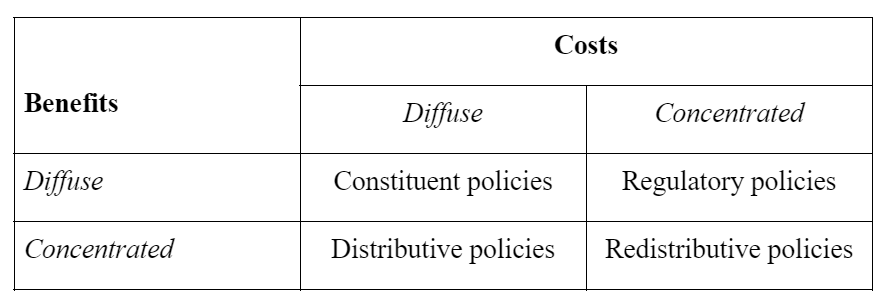

Working at about the same time, Theodore Lowi set out to create a more systematic way of classifying public policies. First in 1964 and then in more detail in 1972, Lowi outlined a method for categorizing public policies based on their impact or expected impact on society in terms of who pays for the policy (costs) and who benefits from the policy (benefits).[4] What Lowi developed is less a theory and more of a system of categorization, but I’m including it here because it was an early attempt to provide a systematic (and predictive) model of policy.

Lowi argued that costs and benefits can be diffuse (spread out among many people) or concentrated among a few. Distributive policies spread the costs out among a large group of people (largely through taxes) but concentrate the benefits among certain recipients. An example of a distributive policy would be a road or school. All people in a state pay taxes that go toward funding roads and schools, but only people who drive on the road or attend the school benefit directly from them. However, even though the immediate benefits are generally fairly concentrated, secondary benefits flow to the broader community and it’s fairly easy to understand those benefits. I might not drive on the road that was built, but maybe traffic on the road I do drive on is reduced because of the other road. Similarly, I benefit from others in society having good education even if I didn’t attend the school and, if I value education, I likely value education for others too. Because we don’t view these government services as mutually exclusive or in competition with each other (we don’t have to choose between a road and a school) and because we understand the broader benefits to society even when they don’t impact us directly, Lowi predicts that policymaking isn’t likely to be very contentious with distributive policies. Distributive policies create a lot of winners and very few losers because the costs are shared so broadly among members of society that most people don’t even notice the burden and the benefits are easily recognizable.

In contrast, regulatory policies concentrate the costs among a few people but distribute the benefits widely. Regulatory policies create rules and restrictions that impact individuals and businesses for the benefit of protecting the health, welfare, and safety of the public. Some scholars further differentiate between competitive regulatory policies and protective regulatory policy. Competitive regulatory policies control who is allowed to enter a market. When the government requires a doctor to have a license to practice medicine, it is establishing a competitive regulatory policy. Protective regulatory policies protect the public from harm. Restrictions on auto emissions or regulations on food producers are examples of protective regulatory policies. Regulatory policies limit the activities of individuals and businesses or require them to spend additional resources in order to meet government requirements. The broader community benefits from the regulation, but it is the individual or business that bears the cost. Regulatory policies can get controversial, but often the individuals and businesses being regulated have a large role to play in the creation or enforcement of the regulations.

Redistributive policies have concentrated costs and concentrated benefits, but the group that pays the costs is different from the group that gets the benefits. Most examples of this type of policy are related to income (social welfare policies that provide income support to the poor from taxes paid by the wealthy), but the groups could be based on age, race, gender, or any other division. Affirmative Action is viewed as a redistributive policy, shifting benefits of jobs from one racial group (white) to another (Black, Latinx, Asian, etc.). As you might expect, redistributive policies tend to be very controversial because they change the distribution of resources.

The fourth category in the Lowi Typology is constituent policies and these are policies that change government rules and structures. Constituent policies have broad costs and broad benefits. Lowi predicts that constituent policies will not be very controversial because not many people care about the rules and procedures of government other than the people who work in government.

Figure 1.3: Lowi Typology

Lowi’s typology offered a big step in trying to think about how different policies were related in terms of more than just topic. It provided some testable hypotheses (policymaking for these kinds of policies should look like this) and called our attention to some of the important dynamics that shape policymaking like the allocation of benefits and burdens. However, as you have probably already noticed, there are some big flaws. First, not every policy fits neatly into a category; some policies have elements of multiple categories. Second, the distinction between distributive and redistributive policies is very much in the eye of the beholder; nearly every policy could be classified as redistributive, if you think about it in that way. In short, Lowi’s typology doesn’t provide definitive answers about public policy, but it did help move us along the path of finding more structured ways of classifying and analyzing policy.

The Stages Framework

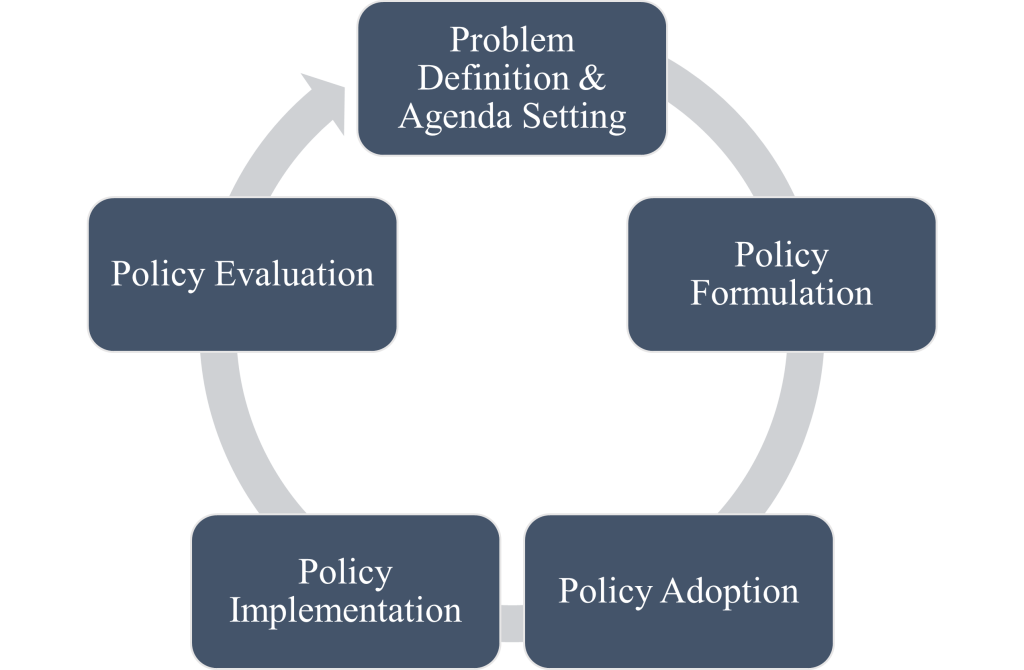

Harold Lasswell gets the credit for conceptualizing the policymaking process as cyclical.[5] Lasswell identified seven distinct stages in the process of policymaking and many subsequent authors built on his idea.[6] The variation of this idea that is most commonly used today is the Stages Framework, also known as the Policy Cycle, outlined by James Anderson, David Brady, and Charles Bullock in 1978.[7] In more recent iterations, Anderson identifies five stages in the policy process: problem definition and agenda setting, policy formulation, policy adoption, policy implementation, and policy evaluation.

Figure 1.4: Stages Framework

In the first stage of the process, problem definition and agenda setting, the focus is on understanding what topics receive attention from policymakers. There are lots of problems in the country, but policymakers don’t care about them all equally and they don’t consider them all at the same time. Problem definition involves defining a situation as something that is worthy of attention from government. Agenda setting involves bringing the topic to the active attention of policymakers. Before any policy is made, government actors need to be aware of the issue and must believe that it is worthy of government attention and action.

In the second stage, policy formulation, government officials develop proposals for addressing the issue. Proposals or policies might originate from legislatures (Congress, at the national level; state legislatures, at the state level; or county commissions, city councils, or school boards, at the local level), executives (the President, governors, or mayors), bureaucrats, or courts. In this stage, policymakers draft the policy to address a problem.

In the third stage, policy adoption, government officials formally adopt the policy. At the federal level, this might involve Congress passing legislation and the President signing it into law. This is the formal process of turning a proposal into a law or regulation.

The fourth stage of the process is policy implementation. Policy implementation involves actually putting the policies that are passed into action. A lot of this work comes down to the administrative agencies and departments that make up the bureaucracy. Implementation happens at all levels of government, from teachers in your local school district who administer curriculum to the federal Internal Revenue Service who collect taxes.

The final stage, policy evaluation, involves efforts by government and other policy actors (like academics!) to find out whether the policy was effective in reaching its intended goals. Government programs cost a lot of money to run and so it is important to most people to make sure that the money is being spent properly and that it is creating the desired effects.

The Policy Cycle framework provides a straightforward and clear description of a very complex topic (policymaking). It calls our attention to important parts of the process and helps us identify some of the predictable elements of the process. However, you’ve probably already noticed that it is a very simplified version of the process. Most policies don’t work in a neat circle and the framework doesn’t help us understand how topics move from one stage to the next or why some of them get stuck at a particular stage or jump around. Nevertheless, this framework gives us an entry point into thinking about the policy process and you’ll notice that the chapters in this book are loosely organized according to this framework.

1.3 But what about the other ways of thinking about public policy?

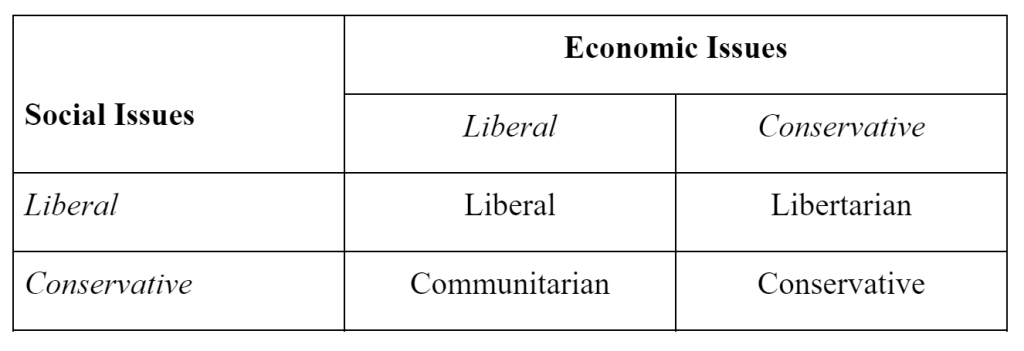

The two frameworks and typology that I describe here are only a handful of approaches scholars have used to bring order to the study of public policy. We’ll explore a few more approaches in later chapters, but I want to take just a minute to address one of the main ways the general public and the media often classify public policy: in ideological terms. When people talk about public policies, you’ll often hear them talk about liberal or conservative policies (or policies favored by liberals or conservatives). Sometimes commentators will also throw in a mention of a political party. Hopefully you remember a bit about political ideology and political parties from previous classes, but it is worth a brief review.

Political Ideology

Ideology refers to an organized set of beliefs about the proper role of government in a society. Much of a person’s ideology is based on their answer to the question of what role the government should play in the economy. If we think about this as a continuum, there are those on one end of the spectrum (commonly referred to as the right side) who believe that the government should play a very minimal role in regulating the economy. These people favor low taxes, fewer regulations on business, and lots of freedom for individuals to operate on their own without government interference. The label we use to describe this ideology today is conservative.[8] On the other side of the spectrum (commonly referred to as the left side), there are people who believe that the government has an important role to play in regulating the economy in order to keep a fair playing field for all. These people favor government spending on programs that benefit people’s health and welfare and they support the government stepping in to regulate businesses in areas like consumer protection and workplace safety. The label we use to describe this ideology is liberal.

But there’s another dimension to ideology besides the economic aspect and that is the question of the role the government should play in regard to social issues, many of which involve questions that are related to race, ethnicity, sex, gender, and religion as well as behavioral decisions. Again, thinking of these on a continuum, there are some people who believe that the government should enforce a traditional social order (right side) while others believe that the government should protect individual rights and privacy even when these conflict with traditional beliefs (left side). It is fairly unhelpful that we also use the terms “conservative” and “liberal” to describe these two positions, respectively. Those who are conservative on social issues might oppose access to abortion, the legalization of recreational marijuana, or the teaching of critical race theory in schools. Those who are liberal on social issues would take the opposition positions on those issues.

The use of the two terms to reflect beliefs about both economic and social issues creates a lot of confusion because when someone identifies as “conservative”, it might mean that they are conservative just on economic issues or just on social issues or it might mean that they are conservative on on both economic and social issues. I think it is most helpful to think about these two dimensions of ideology as intersecting and then consider ideological positions based on both dimensions. Those who are conservative on both economic and social issues are usually called conservatives and those who are liberal on both economic and social issues are usually called liberals. Those who are conservative on economic issues but liberal on social issues are called libertarian. There’s no agreed upon term for those who are liberal on economic issues but conservative on social issues, but Carter Wilson calls this group communitarian.[9]

Figure 1.5: Political Ideology Typology

There are a few other ideological terms that often get mentioned in political discussions. At the far right end of the social continuum (past conservative) is fascism, which advocates for complete control of public life by government. Socialism rests at the far left end of the economic continuum, emphasizing collective ownership of business. Over the past few years, I’ve noticed that many of my students prefer to identify as “radicals”. It would be safe to place those students on the far left of both the economic and social dimensions of ideology.

A person’s ideology is shaped by lots of different factors including their families, friends, education, media consumption, religious beliefs, and personal experiences.

Political Party Affiliation

Closely related to the concept of ideology are political parties. Political parties are organizations of likeminded people who work together to win control of government through elections. Political parties are related to ideology in that the parties have an ideological leaning that is often (but not always!) shared among people who identify as members of the party. This has not always been the case, but the parties have become more ideologically cohesive in recent years. Today, most people who identify as part of the Republican Party hold a conservative or libertarian political ideology, while most people who identify as part of the Democratic Party hold a liberal political ideology.

Even though ideology and party identification closely overlap, it’s important not to use these terms interchangeably because they are still different concepts. In fact, even though the parties are more ideologically cohesive than they used to be, there is still a lot of ideological variation within each of the two major parties. For example, there are Democrats who are far enough to the left ends of the spectrum that they identify as Democratic-Socialists (Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Bernie Sanders, for example) and there are Democrats who consider themselves to be moderates or pragmatists (Representatives Dean Phillips and Angie Craig, for example).

If you read the news about public policies or talk to your family about it, chances are you’ll hear people use ideology and partisanship (support for a particular political party) to describe policies.[10] There’s definitely something to this… liberals and conservatives (and Democrats and Republicans) do have very different views of what policies are best for the U.S.

However, if our analysis of a policy only goes as deep as whether the policy is supported or opposed by a particular political party, we’ll miss a lot of the story. Knowing whether a policy is more liberal or more conservative doesn’t actually tell us very much about whether the policy will get enacted or ignored or how effective it might be. And. there are plenty of examples of a party in control of government failing to pass policies it supports (look no further than the failure of the Republican party to repeal the Affordable Care Act–a top priority for Republicans–when it controlled the House, Senate, and Presidency from 2017-2019).

That said, partisanship and ideology are important factors influencing the development of public policy and they will pop up in every chapter of this book. One way they show up is in the writing produced by people looking to shape policy and the policy process. Before we wrap up with this chapter, let’s take a minute to think specifically about policy writing.

1.4 What kind of writing happens in the field of public policy?

You’ve probably done a lot of writing in your years as a student. One of the most common genres (or types) of writing in an academic situation is a research paper where you collect and summarize information about a topic. You may have been asked to develop a thesis, or an argument, about your topic. This kind of writing assignment is useful in teaching you skills of research, critical analysis, and writing, but the final product (the research paper) is very different from the types of writing you find in the field of public policy.

In this book, I employ a rhetorical approach. The rhetorical approach asks us to consider the purpose and audience for our writing (and for evaluating things we read!) and reminds us that there are different genres (types of writing) all of which have a different set of conventions and expectations associated with them. I think the rhetorical approach is helpful because it gives us the tools to analyze the information we’re reading and to become more flexible and successful writers ourselves.

Everything that you write and everything that you read has a purpose–a reason for writing or a goal of communication–whether you realize it or not. Two of the most common purposes are to inform and to persuade. Informational writing involves providing a reader with information about a topic with the goal of summarizing information and presenting it in a clear and understandable format. Persuasive writing is meant to change someone’s mind about a topic or get them to act (or not act) on a topic. A piece of writing can be both informative and persuasive; they aren’t mutually exclusive. Other purposes in writing might be to evaluate, express, inspire, entertain, or learn. It’s a good idea when you begin the writing process to know what kind of purpose you have, otherwise you might write something persuasive when your boss (or professor) may have wanted something informative. It’s also important to think about purpose when you are reading something…was the author trying to provide you with information (like when you read a newspaper article) or were they trying to persuade you (like when you read an editorial)?

When you write, it’s also important to think about your audience. The audience refers to the intended recipient of your communication. In school, your audience has usually been your professor or teacher. Sometimes you are writing for yourself (like when you take notes or write in a diary). In your future career, you’ll probably be writing for a boss or employees. In the field of public policy, you might be writing for a policymaker (an elected official or bureaucrat) or for the public. Sometimes your audience is very specifically identified either by name or position like, for example, when you write a letter or memo that is addressed to a particular person. Other times, you are writing to a broader audience, like readers of a particular newspaper or website. In the case of both a specific and a general audience, you need to think about who that person or people are that are going to be reading your writing so that you can write effectively for them.

One question to ask about your audience is whether or not they are already knowledgeable about the topic of your writing. Answering this question helps you make decisions about the kind of language and level of detail you will use. If you’re writing to someone who knows a lot about the topic, you can use more technical language and jargon. If you’re writing to someone who knows very little about the topic, you’ll have to explain specialized terms.

When you are writing things that are persuasive in nature, you’ll want to think about whether your audience is likely to be sympathetic, skeptical, or even hostile to your argument. You might need to use different supporting evidence or logical reasoning for different audiences in order to be more effective.

Finally, you want to think about what genre of writing you are doing. Genre refers to the different types of writing that have different styles and writing conventions associated with the genre.

To give you an example, I wrote this textbook. The textbook is a genre that is meant to provide an overview of a topic and a summary of information to a student enrolled in a class. In writing this book, I’ve thought a lot about you (the audience) and your needs. I’ve thought about what terms you’re likely to be familiar with and which ones I might need to explain in more depth. I’ve also thought about the style and tone I should use so that you read this without falling asleep (too often!). I have also spent a lot of time thinking about the purpose of this book. There are lots of public policy textbooks (I’ve looked at over a dozen of them in preparing to write this book!) and so I’ve had to think about the purpose of writing something new. I know that my primary goal is to inform you about this content and I have a secondary goal of persuading you that it is both important and interesting. I’ve asked myself, what are the most important topics you need to know as an undergraduate student taking a course in public policy. Finally, I’ve thought a lot about the textbook genre and looked at a lot of examples of textbooks. I know that textbooks have certain writing conventions and styles like chapters, subheadings, key terms that are highlighted, discussion questions, and supporting material. I want my book to look and read like a textbook rather than like a novel or academic journal article and so I make stylistic choices to reflect this genre.

Learning to identify different genres when you encounter them in the wild is important because it helps us understand and interpret the things we are reading. Knowing what genre we’re reading gives us some insight into the audience and purpose of the text and can help us ask good questions about the text. Recognizing different genres is also the first step in learning how to write in different genres, and this is a critically important skill for anyone who has a job that involves any amount of writing (sorry to break it to you, but most of them do!).

There are tons of different genres–news articles, nonfiction books, and blog posts, to name just a few–but in this book, we’re going to focus on the genres that are common in public policy-related fields. You will read some different genres, including news articles, journal articles, bills and laws, and this textbook. You will also practice writing a few different genres as part of the class. We’ll focus on a different genre in each chapter of this book and I’ve included a bit of bonus material in the appendix.

Over the past few years, the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has revolutionized the workplace. AI can do a lot and it can do it quickly. While it might be tempting to think that there’s no need to develop your writing skills because AI will write everything in the future, I think this would be a mistake. Writing skills–and the critical thinking skills that go along with writing–are going to be more important than ever as AI continues to improve. While anyone can type a prompt into AI, only people with some expertise will know if what it produces is accurate and appropriate for the task. AIs tendency to hallucinate information is particularly problematic. I should also note that AI itself raises all kinds of interesting policy issues, from the location of data centers to harmful environmental impacts. That said, I do think there are lots of ways that AI can be helpful in the writing process and I will include some examples of this throughout the book.

Let’s start with the press release genre.

1.5 What is a press release?

Press releases (also called media releases) are short documents (usually only 1-2 pages in length) that are written to provide basic information about an event or action that is going to happen or that has already happened. Press releases are commonly written and distributed by government officials (such as legislators), but they are also used by advocacy groups, businesses, and nonprofit organizations.

Press releases have two audiences. The main audience for a press release are journalists. This is because the main purpose of a press release is to get the media to cover your story. To do this effectively, a press release needs to look professional, include newsworthy information, and make the job of the journalist easy by providing all of the relevant information.

The second audience for a press release is the public, which often includes policymakers.

The primary purpose of a press release is to inform. A press release might be informing people about an upcoming event or it might be informing them of something that has already happened. A press release might also have another purpose. For example, a Member of Congress issuing a press release about a bill they sponsored might be intended to inform their constituents about the bill but it might also be intended to persuade them that the bill is an important proposal that should be passed.

The press release genre has a very formal structure and most press releases look fairly similar. The words “Media Release”, “News Release,” or “Press Release” are usually clearly written at the top. A press release might include a statement that says “For Immediate Release” to communicate that the information in the document is meant to be shared at the moment it is received. The top section also contains information about the author of the release and contact information.

A press release is written a little like a news article, with an attention grabbing headline; a lede (the first sentences that are meant to grab the readers’ attention) that answers the big questions of who, what, where, when, why, and how; and details provided in an inverted pyramid style. The inverted pyramid is the idea of putting the most important information toward the top of the article and details of lesser importance toward the bottom. A press release will usually include quotations from relevant sources and you might notice that the source names are bolded.

At the bottom, press releases usually include a paragraph that describes the organization or the person issuing the press release. And a press release ends with a marker (usually three hashtags) centered at the bottom to signal the end of the release.

The ultimate goal for most writers of a press release is that media outlets will use a lot of the press release verbatim…in other words, the goal is to basically write the news article for the journalist, which allows the writer of the press release to control how the story is framed and presented to the public.

In addition to sending press releases to media outlets, government officials and other organizations that issue press releases often post them on their websites. As a side note, when you’re researching a topic, press releases can be a very helpful way of figuring out what an individual or organization thinks about a topic. Individuals and organizations use press releases to indicate which issues they care about and to articulate their positions on issues.

Even though the body of a press release can look a lot like a newspaper article, it is important to remember that it is not a newspaper article; press releases are marketing tools not impartial coverage of events. Since press releases are often posted on a website, they can also sometimes look like blog posts, but the information provided at the top of the page should help you recognize it as a press release.

AI can be helpful when generating a press release because it is such a structured genre. As a test, I asked Gemini to “write a press release from a political advocacy organization about an upcoming event.” This very generic prompt resulted in a very useful press release template that could easily be used by a political advocacy group. Notice that AI knew to incorporate a lot of the genre conventions discussed above (“for immediate release,” an inverted pyramid style, a quotation, information about the group, and even the three hashtags at the end). As the policy professional, you still need to fill in the template and adjust it to meet your needs, but using AI to generate the template might be a helpful starting point.

Press Release Template Generated by AI

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

[Date of Release: e.g., November 4, 2025]

[Bold, Punchy Headline Summarizing the Event’s Core Purpose/Goal]

[Subheadline: One sentence expanding on the headline, e.g., “Coalition to Mobilize Hundreds of Advocates for Crucial Vote on Clean Energy Bill X”]

[CITY, STATE] – [Organization Name], a leading advocacy group committed to [briefly state organization’s core mission/issue, e.g., “advancing sustainable infrastructure and climate justice”], today announced it will host a [Type of Event, e.g., “Town Hall, Rally, Advocacy Day”] focused on [Key Policy/Goal of the Event]. The event will take place on [Day of the Week], [Date of Event] at [Time of Event] at [Location Name and Address].

The [Event Name] is being held to [State the main “Why” – what is the immediate objective? e.g., “urge local representatives to support the passage of Senate Bill 101, which would mandate a 50% reduction in local carbon emissions by 2035”]. This legislation is vital because [briefly state the significance/impact, e.g., “it represents the most significant step our city can take to protect public health and secure a livable future for our children”].

Event Details & What to Expect

- Who: The event will feature speeches from [Name and Title of Key Speaker 1, e.g., Coalition Director, State Senator Jane Doe], [Name and Title of Key Speaker 2, e.g., Climate Scientist Dr. John Smith], and several community members directly impacted by [the issue].

- What: Attendees will participate in [Specific Activities, e.g., brief training sessions on contacting legislators, a collective signing of a public petition, and a rally with unified messaging].

- When: [Date of Event] at [Start Time] to [End Time] [Time Zone].

- Where: [Full Address of Venue]. [Optional: Note on accessibility, e.g., “The venue is wheelchair accessible and near the Main Street Metro station.”]

- Call to Action: The organization is urging all concerned citizens to [Clear, Specific CTA, e.g., “RSVP at [Link] to attend” or “Join the digital advocacy campaign at [Link]”].

Quote from Organization Spokesperson:

“This is a critical moment for our community. We cannot afford inaction on [the issue]. Our event on [Date] isn’t just a gathering; it’s a demonstration of the widespread public will demanding that our elected officials stand on the right side of history by passing [Bill/Policy Name],” said [Spokesperson’s Full Name], [Spokesperson’s Title, e.g., Executive Director] of [Organization Name]. “We invite everyone who cares about [The Core Value, e.g., clean air, fair housing, etc.] to join us.”

About [Organization Name] (Boilerplate)

[Organization Name] is a [State your focus, e.g., non-partisan, grassroots, statewide] advocacy organization founded in [Year]. Our mission is to [State your mission in one sentence, e.g., “mobilize the public and influence policy to ensure equitable access to clean water and environmental protection across the state.”] We work to achieve meaningful change through public education, direct action, and legislative engagement.

Media Contact

[Contact Person’s Full Name]

[Title, e.g., Communications Director]

[Email Address]

[Phone Number]

[Organization Website]

###

Take a look at this press release on the Gustavus website: https://news.blog.gustavus.edu/2022/11/22/gustavus-recognized-for-student-voter-participation/ Can you spot the stylistic markers that make it a press release? Who issued it? What media outlets do you think they might have sent this to? What members of the public do you think they hope will read it? What purpose do they have for writing it?

1.6 Why do you write?

Figure 1.6: Henry Adebisi ‘18

I am a current law student at the University of Wisconsin and a former Compliance Analyst of four years at Ameriprise Financial. At Gustavus I studied Political Science but the path to getting that degree was not simple. Originally, I studied Computer Science, with Political Science as a minor. I chose Computer Science because I had an interest in it in high school as a fun hobby, and I enjoyed the coding club led by our teachers. To my dismay, at Gustavus I realized I did not have a strong passion for Computer Science. I put off doing the work for the classes and would find myself reading every single word of my Political Science readings. Unfortunately, as a first-generation college student I felt compelled to complete the degree to maximize my chances of getting a well-paying job. I want to assuage anyone’s worry who is reading this— it is okay for your passions to change. Pursue the degree that makes you passionate and hungry to learn. In my case, my hunger and passion were a perfect fit in the Political Science department at Gustavus, and later at the University of Wisconsin Law School.

As a Compliance Analyst, my focus was monitoring new and upcoming regulations and law by the SEC, FINRA, and state legislatures. In my role I reported to two teams. On team one, my focus was communicating the new regulations and helping the business implement the changes and monitoring the changes through audits. For the second team, I worked with leaders in the company to create training to educate the entire company on upcoming regulatory changes or legal topics the company leaders wanted to address.

I wrote concisely to convey ideas and decisions. I wrote to team members, teams I audited, or high-level senior leaders. This was in the form of emails, reports, and company-wide training. Often, I would read 10-30 pages of new regulations and I would have to condense down the main findings to one page of training or a short email. Often, I would read 10-30 pages of new regulations and I would have to condense down the main findings to one page of training or a short email. This style of writing was jarring to me at first, because of the perceived contrast to academic writing. The focus was not to sound smart but rather to convey my ideas to people who would read them quickly. While this sounds easy, it is a skill that I still have trouble mastering, and it’s now a part of my editing process.

As a law student, I research and write to answer legal questions simulating the type of legal questions a client and then ultimately a supervising attorney could ask me. I used to think of legal writing as long-winded Latin filled documents, but the legal writing faculty actively fought this misconception. The professors consistently said do not write to sound like a lawyer but rather focus on communicating complex legal ideas or arguments in an accessible manner. The main form of writing here is objective legal memos that answer clients and supervise attorneys’ legal questions.

When I research a new topic, I strive to keep it all condensed into one document on Word that I can reference. This document will often contain hyperlinks and snippets of what I want to directly include in my writing. I also now include a sentence of why a snippet or link is relevant, because I found I forgot why a law, policy, or article was relevant without some context.

My writing process begins with an outline. I think it’s helpful to consider how your final document will ultimately be organized. Outlining is also helpful for me because I have a tendency to write in a scattershot way and so it helps me stay focused and concise. After I finish my first draft, I revise that draft a subsequent day so I can catch any minor mistakes and see if it makes sense. I continue my editing process referencing a document that I made for myself that includes common mistakes I make. To conclude I try to seek a peer review, because I find that sometimes I may write something that’s great to me but is not clear to someone else.

What I’ve learned about writing is that often it is not how smart you are that dictates how well your writing will be perceived. The most valuable asset you can lend your writing is time. What I’ve learned about writing is that often it is not how smart you are that dictates how well your writing will be perceived. The most valuable asset you can lend your writing is time. This was something I struggled with coming from high school where I could write a paper the night before and still do well. My first college papers were graded harshly, and I thought this was more reflective of my intelligence instead of realizing I need to give my papers more time. The polish and level of nuance professors and later employers are expecting you to engage in is not something that can be accomplished the night before. I now try to finish my papers 3-4 days before the due date. That way each day I can edit the paper in a small and focused way. One day can be sentence clarity, the next day punctuation, another day passive voice and so forth. Obviously, you cannot control the time you have for every paper, but especially in the school context where a syllabus dictates the semester, strive to give your papers more attention and time.

1.7 What comes next?

In this chapter, we learned a basic definition for public policy and policymaking. We were introduced to a few of the early attempts to make sense of policy and policymaking and talked a bit about the impact of ideology and partisanship. And we learned about the genre of press releases. In the next chapter, we’ll find out more about the people involved in the policymaking process.

Questions for Discussion

- What are some of the public policies that impact your life the most? How much do you know about them and how did you learn what you know? What questions do you have about these policies?

- Where do you fall ideologically? What factors do you think impacted your ideology? Do you identify with a political party? Why or why not? What factors do you think impacted your party affiliation (or lack thereof)?

- Do you enjoy writing? Why or why not? What kind of writing (genres) are you most familiar with or comfortable with? What is your writing process like?

- What questions does the material in this chapter raise for you about public policy, the policymaking process, or writing about public policy?

Glossary

Agenda Setting: Bringing the topic to the active attention of policymakers.

Audience: The intended recipient of your communication.

Communitarian: liberal on economic issues but conservative on social issues

Competitive Regulatory Policies: Public policies that control who is allowed to enter a market.

Constituent Policies: Public policies that change the rules and structures for how the government operates.

Conservatives: Those who believe the government should play a limited role in the economy but should play an active role in preserving traditional morals and values.

Distributive Policies: Public policies that spread the costs of a policy out among a large group of people (largely through taxes) but concentrate the benefits among certain recipients.

Domestic: Focuses on the policies and policy proposals that affect things within the United States rather than in foreign policy or the policies of other nation states.

DREAM Act: The DREAM Act is a policy proposal that would protect a group of undocumented immigrants who came to the United States as children. The full name of the proposal is the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act. It was first introduced into Congress in 2001 but it has not yet been enacted into law.

Fascism: Rests at the far right end of the ideological continuum, advocating for complete control of public life by government.

Feedback: Feedback refers to the way the outcomes or effects of a public policy influences the development of new policies or the revision of existing policies.

Genre: The different types of writing that have different styles and writing conventions associated with the genre.

Government: The institutions operating at the national (federal), state, and local level to structure social interactions within a community.

Gross Domestic Product: The GDP is a measure of economic activity that reflects the monetary value of the goods and services produced in a country within a specific year.

Ideology: An organized set of beliefs about the proper role of government in a society. Liberal and conservative are two of the main terms associated with ideology.

Institutions: Any of the bodies that are designed to formulate and implement public policy including legislatures, executives, bureaucratic agencies, and courts.

Inputs: Demands for action that come from individuals and groups as well as the support for the system that comes when individuals and groups accept the system of government, for example by paying taxes, obeying laws, and abiding by results of elections.

Inverted Pyramid: This term is related to news articles and involves putting the most important information toward the top of the article and details of lesser importance toward the bottom.

Lede: This term is related to news articles and references in the first sentences in an article that are meant to grab the readers’ attention; answers the big questions of who, what, where, when, why, and how; and details provided in an inverted pyramid style.

Liberal: Those who believe the government should play an active role in regulating the economy but should play a limited role in preserving traditional morals and values.

Libertarian: Those who believe that the government should play a limited role in regulating the economy and should also play a limited role in preserving traditional morals and values.

Outputs: In the political system, outputs are the policies such as laws, court decisions, and bureaucratic regulations.

Partisanship: Support for a particular political party.

Persuasive Writing: This type of writing is intended to change someone’s mind about a topic or get them to act (or not act) on a topic.

Policymaking: The processes of designing, passing, and implementing a government policy.

Policy Formulation: The process of designing and passing a government policy.

Policy Adoption: The process of formally adopting a government policy.

Policy Implementation: The process of actually putting the government policies that are passed into action.

Policy Evaluation: Efforts by government and other policy actors (like academics!) to find out whether the policy was effective in reaching its intended goals.

Political Systems Model: This theory of policymaking conceives the process as involving inputs and outputs into a political system embedded within an environment.

Political Parties: Organizations of likeminded people who work together to win control of government through elections and that help to structure and organize the policymaking process.

Press releases: Short documents (usually only 1-2 pages in length) that are written to provide basic information about an event or action that is going to happen or that has already happened. (Also called media releases)

Problem Definition: Defining a situation as something that is worthy of attention from the government.

Protective Regulatory Policies: Public policies that are designed to protect the public from harm.

Public Policy: The authoritative statements and actions of the government that reflect what governments choose to do or not to do.

Purpose: A reason for writing or a goal of communication. Common purposes include informing, summarizing, persuading, encouraging, and entertaining.

Redistributive Policies: Public policies that have concentrated costs and concentrated benefits, but the group that pays the costs is different from the group that gets the benefits.

Regulatory Policies: Public politics that concentrate the costs among a few people but distribute the benefits widely.

Rhetorical Approach: This approach to analyzing written texts asks us to consider the purpose and audience for our writing (and for evaluating things we read!) and reminds us that there are different genres (types of writing) all of which have a different set of conventions and expectations associated with them.

Socialism: This ideological perspective rests at the far left end of the economic continuum, emphasizing collective ownership of business.

Theory: Provides an outline of how a process works and calls attention to certain key aspects of the process. It is meant to explain what has happened in the past and to help us make predictions for future policymaking.

Additional Resources

The New York Times: Reading the U.S. news section of The New York Times each day is a great way to stay up to date on current political events. A subscription to the New York Times is free to Gustavus students: http://orgs.gustavus.edu/senate/documents/OnlineReadershipDocNov2022.pdf

The Pew Political Typology: The Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan (no political party affiliation) research organization that focuses on politics and social issues. They’ve created a short ideology quiz for the purpose of better understanding the political beliefs of people in the U.S.

Thanks for reading this chapter. The book in which this chapter sits is a work in progress and I welcome feedback and suggestions for improvement. If you notice incorrect or out of date information, please let me know using the feedback form linked below. If something was particularly helpful to you, I’d also love to hear about it. If you are a faculty member or public policy practitioner who is interested in collaborating on this project, you can also use this feedback form to contact me. ~Kate

Feedback form: https://forms.gle/LKBykHHRLe2kNW2AA

- Anne Schneider and Helen Ingram, “Social Construction of Target Populations: Implications for Politics and Policy,” American Political Science Review 87, No. 2 (June 1993): 334-347. ↵

- Carter Wilson defines public policy as “the authoritative statements or actions of government which reflect the decisions, values, or goals of policymakers” [Carter Wilson, Public Policy: Continuity and Change 3rd Edition (Illinois, Waveland Press, Inc., 2019),17] while Thomas Dye [Thomas Dye, Understanding Public Policy (New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1987), 1] defines public policy as “whatever governments choose to do or not to do.” ↵

- David Easton, “An Approach to the Analysis of Political Systems,” World Politics 9, no. 3 (April 1957): 383-400; David Easton, A Systems Analysis of Political Life (New York: Wiley, 1965). ↵

- Theodore J. Lowi, “American Business, Public Policy, Case-Studies, and Political Theory,” review of American Business and Public Policy: The Politics of Foreign Trade, by Raymond A. Bauer, Ithiel de Sola Pool, and Lewis Dexter, World Politics 16, No. 4 (July 1964): 677-715; Theodore J. Lowi, “Four Systems of Policy, Politics, and Choice,” Public Administration Review 32, No. 4 (1972): 298-310. ↵

- In fact, Lasswell is credited as being the founder of “policy sciences” through his 1951 chapter. [Harold, Lasswell, “The Policy Orientation” in The Policy Sciences: Recent Developments in Scope and Method, ed. Daniel Lerner and Harold Lasswell (California: Stanford University Press, 1951), 3-15.] ↵

- Harold Lasswell, The Decision Process (Maryland: University of Maryland Press, 1956). ↵

- James Anderson, David Brady, and Charles Bullock, Public Policy and Politics in America (Massachusetts: Duxbury Press, 1978). This version of the framework outlined six stages: Problem formation, policy agenda, policy formulation, policy adoption, policy implementation, and policy evaluation (p. 8). ↵

- The definitions of the terms conservative and liberal have changed a lot over time and are likely to change again in the future. ↵

- Carter Wilson, Public Policy: Continuity and Change 3rd Edition (Illinois, Waveland Press, Inc., 2019), 29. ↵

- When people use the term [pb_glossary id="90"]bipartisan[/pb_glossary], it means that members of both parties worked together on something. ↵

The DREAM Act is a policy proposal that would protect a group of undocumented immigrants who came to the United States as children. The full name of the proposal is the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act. It was first introduced into Congress in 2001 but it has not yet been enacted into law.

The authoritative statements and actions of the government that reflect what governments choose to do or not to do.

The processes of designing, passing, and implementing a government policy.

Focuses on the policies and policy proposals that affect things within the United States rather than in foreign policy or the policies of other nation states.

The institutions operating at the national (federal), state, and local level to structure social interactions within a community.

Any of the bodies that are designed to formulate and implement public policy including legislatures, executives, bureaucratic agencies, and courts.

Provides an outline of how a process works and calls attention to certain key aspects of the process. It is meant to explain what has happened in the past and to help us make predictions for future policymaking.

This theory of policymaking conceives the process as involving inputs and outputs into a political system embedded within an environment.

Demands for action that come from individuals and groups as well as the support for the system that comes when individuals and groups accept the system of government, for example by paying taxes, obeying laws, and abiding by results of elections.

In the political system, outputs are the policies such as laws, court decisions, and bureaucratic regulations.

Feedback refers to the way the outcomes or effects of a public policy influences the development of new policies or the revision of existing policies.

The GDP is a measure of economic activity that reflects the monetary value of the goods and services produced in a country within a specific year.

Public policies that spread the costs of a policy out among a large group of people (largely through taxes) but concentrate the benefits among certain recipients.

Public politics that concentrate the costs among a few people but distribute the benefits widely.

Public policies that control who is allowed to enter a market.

Public policies that are designed to protect the public from harm.

Public policies that have concentrated costs and concentrated benefits, but the group that pays the costs is different from the group that gets the benefits.

Public policies that change the rules and structures for how the government operates.

Defining a situation as something that is worthy of attention from the government.

Bringing the topic to the active attention of policymakers.

The process of designing and passing a government policy.

The process of formally adopting a government policy.

The process of actually putting the government policies that are passed into action.

Efforts by government and other policy actors (like academics!) to find out whether the policy was effective in reaching its intended goals.

An organized set of beliefs about the proper role of government in a society. Liberal and conservative are two of the main terms associated with ideology.

Those who believe the government should play a limited role in the economy but should play an active role in preserving traditional morals and values.

Those who believe the government should play an active role in regulating the economy but should play a limited role in preserving traditional morals and values.

Those who believe that the government should play a limited role in regulating the economy and should also play a limited role in preserving traditional morals and values.

Political ideology that is liberal on economic issues but conservative on social issues.

Rests at the far right end of the ideological continuum, advocating for complete control of public life by government.

This ideological perspective rests at the far left end of the economic continuum, emphasizing collective ownership of business.

Organizations of likeminded people who work together to win control of government through elections and that help to structure and organize the policymaking process.

Support for a particular political party.

Officially titled the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and more commonly known as "Obamacare," the ACA was enacted in 2010 and changed nearly every aspect of the U.S. healthcare system by expanding eligibility for Medicaid and creating new requirements for insurance companies.

A reason for writing or a goal of communication. Common purposes include informing, summarizing, persuading, encouraging, and entertaining.

This type of writing is intended to change someone’s mind about a topic or get them to act (or not act) on a topic.

The intended recipient of your communication.

The different types of writing that have different styles and writing conventions associated with the genre.

The process of using computers to perform tasks that usually require human intelligence by using machine learning techniques on large collections of data.

Hallucination is when an artificial intelligence system generates incorrect information that sounds plausible. Hallucinations can be minor factual errors, but AI can also completely fabricate facts, citations, or even images.

Short documents (usually only 1-2 pages in length) that are written to provide basic information about an event or action that is going to happen or that has already happened. (Also called media releases)

This term is related to news articles and references in the first sentences in an article that are meant to grab the readers’ attention; answers the big questions of who, what, where, when, why, and how; and details provided in an inverted pyramid style.

This term is related to news articles and involves putting the most important information toward the top of the article and details of lesser importance toward the bottom.

This theory of policymaking conceives the process as involving inputs and outputs into a political system embedded within an environment.

This approach to analyzing written texts asks us to consider the purpose and audience for our writing (and for evaluating things we read!) and reminds us that there are different genres (types of writing) all of which have a different set of conventions and expectations associated with them.

Provides an outline of how a process works and calls attention to certain key aspects of the process. It is meant to explain what has happened in the past and to help us make predictions for future policymaking.