6 Does It Work?

Katherine Knutson and Marcus Schmit

Wondering why some text is in blue? Click here for more information.

6.0 How do we know if it works?

What do you think about the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022)?[1] Are state bans on using public funds to provide gender-affirming care to transgender teens a good idea?[2] What is your opinion of state laws legalizing the sale of marijuana for recreational purposes?

If you have strong thoughts about any of these policies–which I suspect you do–you’re already playing the role of policy evaluator. It’s likely that your evaluation of these policies is anecdotal; that is, it is likely based on your own personal experiences or the experiences of people you know, though it might also be based on things you have learned in the news, in school, or through your own personal research on the topic.

In practice, a lot of what passes as policy evaluation is anecdotal. We (both individuals and society as a whole) make informal judgements about the effectiveness of policies all of the time. A bad experience signing up for health insurance shapes our view of health care policy, a relative’s effort to gain legal authorization to work in the United States shapes our view of immigration policy, a newspaper article about a case of child abuse that ended in a death shapes our view of child welfare policy. Just as true as this is for us, it is also true for policymakers, who have their own personal life experiences with public policy and who are on the receiving end of thousands of stories from constituents and advocacy groups.

Anecdotal evidence is definitely important and personal anecdotes can help us to understand the impact of public policies, but in the study of public policy, we view anecdotal evidence as a supplement to (not a replacement for) empirical evidence. In contrast, empirical evidence involves systematic and objective evaluation of data using quantitative and/or qualitative social scientific research techniques.

Empirical evidence includes measures of policy outputs. Policy outputs are the actions that a government agency takes or the things that a government agency produces in the process of implementing a policy. For example, the number of people who receive Supplemental Assistance for Needy Families (food stamps) in a given year or the average dollar amount of SNAP benefits awarded per household are examples of measures of outputs. In general, policy outputs can be easily counted or measured.

Empirical evidence also includes measures of policy outcomes. Policy outcomes are the results or consequences of policy. Policy outcomes may be intended or unintended and outcomes may affect more than the initial target population. It can be helpful to think of policy outcomes as the impact that the policy had on society rather than simply a measure of government activity or production. Policy outcomes include things like reducing poverty or improving safety. Outcomes are more difficult to measure than outputs.

In attempting to measure outputs, policy evaluators often rely on more complex research designs that establish the causal relationships between public policies and outcomes such as experimental or quasi-experimental design, and before-and-after studies (more about this a little later…). Empirical analysis can help us to understand whether a person’s individual (anecdotal) experience is representative of the experience of others.

In this chapter, we explore the important question of whether policy works; that is, does a particular policy achieve its purpose or goal? Efforts to answer this question are at the heart of policy evaluation. Before we jump into this topic, let’s take a moment to define policy evaluation and distinguish it from the closely related task of policy analysis.

Policy evaluation is a backwards-looking process, focused on using data about existing policies to identify and understand successes and failures related to implementation and policy effects. Policy evaluation is used to discover whether a policy has been effective in achieving its stated purpose or goal. It is also used to analyze the effectiveness of the implementation or administration of the policy.

In many ways, policy evaluation is the inverse of policy analysis, which is a forward-looking process using data to make predictions about the effect and effectiveness of proposed public policies. Policy analysts help policymakers understand the potential consequences of a particular alternative. Whether backwards-looking evaluation or forwards-looking analysis, both processes rely on similar techniques and foundational concepts. Most of this chapter focuses on policy evaluation (does it work?), but the writing focus in this chapter introduces techniques used in policy analysis (will it work?).

6.1 Why do we evaluate policy?

In 2023, the federal government spent $6.13 trillion.[3] To put this in perspective, a stack of one trillion one-dollar bills would reach 67,866 miles high. Now multiply that by six and add a bit more! Add to that the spending by the 50 state governments and we are talking about a lot of money spent on public policy every single year so you can see why it might be important that we make the effort to understand if that money is being well spent. Do the policies we pass work in addressing problems? Are they being administered effectively? These two questions highlight the two central reasons why we evaluate policy: for learning and for accountability.

Good policy evaluation will help us learn whether the policy works or not to help policymakers develop better policies and to help policy implementers find more effective ways of turning ideas into action. Good policy evaluation also helps hold the government accountable to serving the people it represents by ensuring that the money spent is well used.

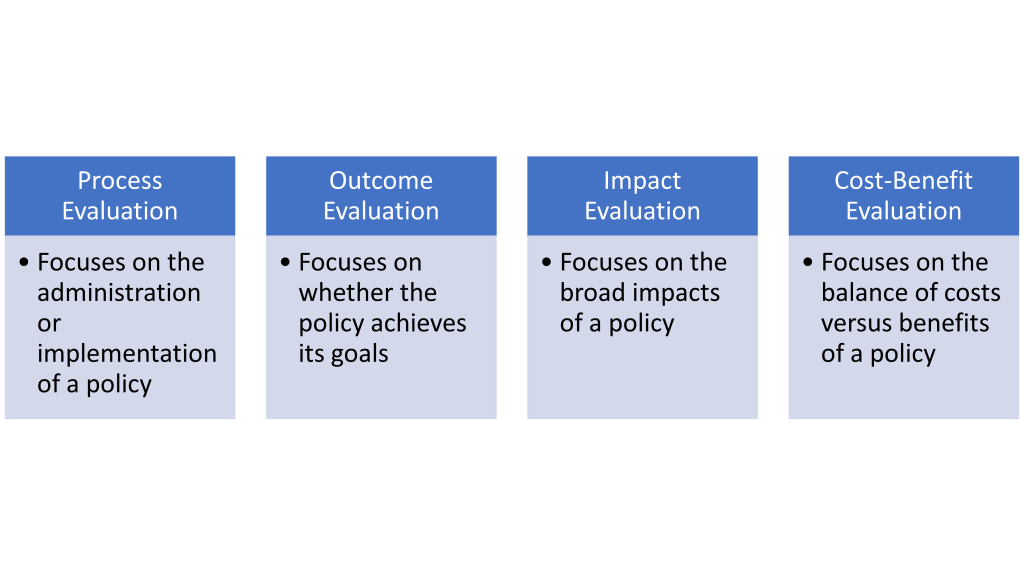

Learning and accountability are at the heart of all policy evaluation. There are, however, multiple types of evaluations and multiple methodological approaches to evaluation. In this section, I’ll highlight four common types of evaluation and in the following section, I’ll summarize some of the different methodological approaches to evaluation.[4]

Figure 6.1: Four Types of Evaluation

Process evaluation, sometimes called implementation evaluation, focuses on how well a policy is administered (or implemented). This type of evaluation focuses on the delivery mechanisms for the policy and asks whether the people or agencies that are carrying out the policy are doing it effectively or efficiently. This type of evaluation is useful when there is a problem in implementing a policy that has to do with the administration of the policy rather than the policy itself.

Outcome evaluation focuses on what the government produces as a result of the policy.[5] This type of evaluation looks at both outputs (what the government produces) and outcomes (the degree to which the policy achieves its intended goals and purposes). Outcome evaluation focuses on whether the policy has achieved its goals.

Impact evaluation moves beyond outcome evaluation to explore the impacts of a policy on various target populations. Rather than simply ask whether the policy has achieved its intended goals, this evaluation approach looks more broadly at all of the impacts of a policy. These impacts may include intended or unintended consequences.

Cost-benefit evaluation focuses on establishing the balance of costs versus benefits associated with a policy to determine whether the benefits outweigh the costs. There are four primary steps in a cost-benefit analysis.[6] First, the researcher identifies all of the long-term and short-term effects or consequences of a policy and categorizes them each as either costs or benefits. During this step, the researcher should consider the various target populations impacted by the policy and include both direct and indirect effects of the policy. Second, the researcher puts a monetary value on the costs and benefits. Third, the researcher accounts for inflation over time. And finally, the researcher compares the total value of costs and benefits to see whether costs outweigh the benefits or the benefits outweigh the costs.

There are reasons a policy evaluator might choose one type of evaluation over another, but a primary motivation comes from what the evaluator was tasked with doing by their supervisor or client. A bureaucrat might be asked to evaluate the implementation of a relatively new policy to ensure that it is working as planned (process evaluation). A legislative aid might be asked by the legislator for information about whether a policy is effective in reducing poverty before the legislator decides whether or not to reauthorize the program for another five years (outcome evaluation). Researchers at a university might be interested in understanding the long-term effects on indigenous families as a result of the Indian Child Welfare Act (impact evaluation). A non-profit agency might be interested in whether a particular policy is worth the cost compared to other options (cost-benefit evaluation). These different reasons, or motivations, will drive the policy evaluation.

6.2 How do we evaluate policy?

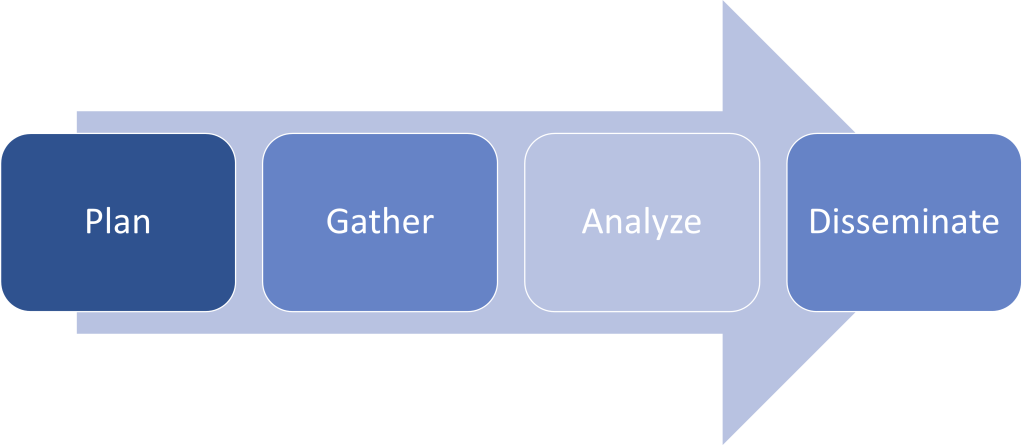

There are several very thorough guides that provide detailed instructions for conducting policy evaluations. I recommend two in particular: The Magenta Book is produced by the British government to guide the process of government policy evaluation[7] and A Guide to Measuring Advocacy and Policy was produced on behalf of the Annie E. Casey Foundation specifically to help guide nonprofits who engage in evaluation of both policy and advocacy work.[8] Rather than rewrite these guides, this section will provide a brief overview of the main steps in the evaluation process, highlighting some of the challenges facing policy evaluators in each stage.

Scholars differ as to how many steps there are in the process of policy evaluation. Theodoulou and Kofinis identify three: plan, gather data, and disseminate the results. The Magenta Book lists five. Bardach and Patashnik identify eight, which they condense into two: “All of your time doing a policy analysis is spent on two activities: thinking (sometimes aloud and sometimes with others) and hustling data that can be turned into evidence. Of these two activities, thinking is generally the more important, but hustling data takes much more time…”[9] There’s clearly no magic number, so in this section, I’ll summarize four steps that I think are worth mentioning in the process of policy evaluation: Plan, Gather, Analyze, and Disseminate.

Figure 6.2: Stages of Policy Evaluation

Plan

As Bardach and Patashnik argue, the planning stage is perhaps the most important part of policy evaluation. Without thoughtful planning, a policy evaluation is unlikely to produce useful results. During this first part of the process, a policy evaluator should devote time to thinking about the following five areas.

First, the evaluator must decide what kind of evaluation is best (see the four main types listed in the previous section). Generally, this will be set by the person asking you to do the evaluation, but it is important at the outset to know for what purpose the evaluation is taking place.

Second, the evaluator should take time to learn about the policy itself and the intended goals and objectives of the policy. The evaluator should be able to articulate what is called a “theory of change” in the nonprofit world. In other words, when the policy was designed, what was the expected causal chain between the policy and the desired outcomes? How was the policy supposed to work?

Third, the evaluator should formulate a primary research question to help guide the research. The evaluator may have more than one research question, but articulating a clear question or a small handful of questions will help keep research efforts focused. A good policy evaluator is going to formulate a relatively narrow research question that appropriately responds to the purpose of the evaluation.

Fourth, the evaluator should identify and define key concepts that will be explored in the evaluation and consider how those concepts might be measured.[10] For example, if a policy’s goal was to reduce poverty among a particular target population, how might you define and measure “poverty”? As with academic research, definitions are important and a policy evaluator should take the time to provide clear definitions of concepts and explain how those concepts are measured.

Finally, the evaluator should brainstorm key indicators that could be used to evaluate the policy and begin to consider options for collecting data that will help to answer the research question(s). Will you simply need to collect output data or will you need to develop a research design to identify causal relationships between the policy and outcomes?

In this planning stage of the evaluation process, several challenges emerge that are important to mention. Both James Anderson and Theodoulou and Kofinis note that the policy being evaluated may have ambiguous goals or ambiguous target populations that can make it difficult for the evaluator to clearly articulate and operationalize. Ambiguity can lead to problems with internal validity in the research; that is, is the research actually measuring the thing that the researcher is trying to measure?

To summarize this stage of the process, before jumping into the research, the policy evaluator should become familiar with the policy and be able to articulate the original goals and objectives the policy was intended to achieve. From there, taking the time to develop a clear research question and operational definitions for any key concepts is critical.

Gather

Once the policy evaluator understands the original purpose of the policy and has a clear research question in mind, it is time to “hustle” the data. There is a lot of information out there and a researcher could spend years gathering various tidbits of interesting information. But unless you’re a college professor, most employers are going to be interested in getting results and getting results in a timely manner means that you need to focus your data collection efforts.

Relevant outputs might be important to gather during this stage. How much did the government spend on the program? Where did the money go? How many people were served? Output information is often available via government sources and a librarian can be really helpful at this stage of the process in helping track down this type of information.

Sometimes a policy evaluation only requires output data and the evaluator can move on to analysis. But your evaluation question might also require a more sophisticated research design using social science research techniques. This isn’t a research methods textbook, but I’ll briefly describe a few common research designs used in policy evaluation.[11]

An experimental design is generally considered the gold standard in social science for establishing causality (that one thing caused something else to happen), but in policy research, the experiments happen in the real world rather than in a laboratory setting, which means there is always room for side effects from other factors. In an experimental research design, an experimental group and a control group are randomly selected from a target population. The experimental group receives the benefit of the policy (the treatment) and the control group does not. Then the two groups are studied to determine the impact of the policy. In 2020, researchers working with the city of St. Paul used an experimental design to test the impact of a guaranteed minimum income policy by randomly selecting some St. Paul residents to receive a monthly payment and then studying the effects on both the treatment group and a control group that didn’t receive payments.[12]

When an experimental approach is not possible, researchers might opt for a quasi-experimental design, sometimes called a natural experiment. The main difference between the two is that a quasi-experiment doesn’t include random selection of participants, but the researchers still attempt to control for as many different factors (variables) as possible. A researcher might compare two or more states or cities, for example. In one foundational study of the impact of a minimum wage increase, economists David Card and Alan Krueger explored the impact of New Jersey’s increased minimum wage by using Pennsylvania as the control group.[13]

A third type of research design is a before-and-after study. Here researchers look at data from before a policy was implemented and compare it to data from after a policy was implemented. Researchers could use either a qualitative approach (like case studies) or a quantitative approach (like a time series analysis) to compare conditions before and after a policy was implemented. The Department of Health and Human Services used this approach in a report about the impact of the Affordable Care Act on access to preventative health care.[14]

Finally, researchers might employ statistical methods, like regression analysis, to analyze data as a way of establishing causal relationships. Frank Baumgartner, Derek Epp, and Kelsey Shoub looked at data collected from over 20 million traffic stops in North Carolina between 2002 and 2016 to explore the prevalence of racial profiling.[15]

There are challenges inherent in each of these research designs. Experimental designs are very useful in establishing causality, but they can also raise ethical concerns because some people receive benefits while others are excluded from those benefits. Quasi-experimental and non-experimental designs can make it difficult to disentangle the multiple factors that might impact a given outcome. Did the policy cause an outcome or was that outcome the result of another policy or some other factor altogether? All of these approaches raise questions of external validity: can a finding from this type of study be generalized to other venues?

In addition to challenges with establishing causality and external validity, each of these social scientific methods can also run into the problem of having a limited time perspective. Will effects identified in a before-and-after study or a natural experiment hold up over the long term or are they just a short term blip? Has the policy had enough time to actually work or will it take longer before we see positive outcomes?

Finally, acquiring the data can be a challenge. The data might be too expensive or time consuming to collect or it simply might not exist. The study I mentioned by Baumgartner, Epp, and Shoub was only possible because North Carolina passed a law in 1999 that required the State Highway Patrol to record the sex, race, and ethnicity of the driver in every traffic stop.[16] Without that law, the data used in that study would not exist.

Analyze

Once an evaluator has collected the data, the next step is to analyze it. What do the data say about the research question?[17] During this step, the policy evaluator is turning raw data (facts and statistics) into meaningful information and evidence. It is important that the evaluator not assume that “the data speaks for itself.” In many ways, this is a continuation of thinking that happened during the planning stage because the evaluator is comparing the results found through the data to the original goals and objectives.

Disseminate

The final stage in policy evaluation is to disseminate the results. This often involves some sort of writing, but it could also involve an oral presentation. Written results from a policy evaluation might take the form of a full report, policy brief, or issue brief. Results from a policy evaluation might also be summarized in news articles, legislative testimony, an op-ed, or other advocacy genres.

Because there are so many different formats for the dissemination of policy evaluation, I will simply emphasize a few reminders.

When an evaluator is presenting the results of a policy evaluation, they should explain the methodological approach and identify the source(es) of data used in the evaluation. The information will be more persuasive and credible if your reader/listener knows how and where it came from.

Second, the evaluator should summarize the results (either through words or through tables, graphs, and/or figures) and explain what they mean (present your analysis). Again, remember that the data doesn’t speak for itself; the evaluator has to explain its significance to their audience.

Third, the evaluator needs to be honest about what the evaluation does and does not show. Credibility as a policy evaluator rests on your ability to be truthful with the data. Manipulating data to “find” a particular result does nothing to advance the two primary goals of evaluation: learning and accountability.

At this stage, aside from the challenges associated with clear writing (see the section later in this chapter for advice on writing policy analysis documents), evaluators might also run into political challenges. Official actors may resist contributing to, accepting, or responding to policy evaluation. Resistance might stem from ideological or partisan beliefs and loyalties or it might come from attempts to maintain control or power. A policy evaluation might be ignored by agencies or elected officials or it might even be attacked.

Now that we know what a policy evaluation is and how it’s done, we can talk about two more important questions. First, who is involved in policy analysis and second, what happens with the information produced by an evaluation?

6.3 Who evaluates policy?

Have you heard of the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act, known colloquially as the “Evidence Act”? I hadn’t heard of it either until I started working on this chapter. The Evidence Act was signed into law in 2019 after being shepherded through Congress by former House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) and Senator Patty Murray (D-WA).[18] It was inspired by a report from the 2017 U.S. Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking. The Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking was created by an act of Congress to study how the federal government uses evidence to make decisions about public policy and to make recommendations for improving the government’s use of evidence in decision-making.[19] The Evidence Act requires federal agencies to develop plans for using evidence to evaluate the policies they oversee, meaning that bureaucrats are definitely important sources of policy evaluation. But they’re not the only ones who do policy evaluation, so let’s take a moment to explore some of the key actors.

Official actors clearly play a big role in policy evaluation. At the federal level, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) is a non-partisan, independent agency that conducts policy evaluations on behalf of Congress and executive agencies.[20] Congressional committees, subcommittees, or individual members of Congress can request an evaluation of a federal policy to determine how well the policy meets its objectives.[21]

The Office of Management and Budget serves a similar function for the executive branch, examining the effectiveness of agency programs and administration.[22] And, of course, the agencies themselves conduct evaluations of the policies they oversee through evaluation plans that are mandated by the Evidence Act. Most federal agencies also have an Inspector General, who has the responsibility of mostly process-type evaluations to prevent fraud, waste, and abuse.[23]

States also engage in evaluation. In Minnesota, the Impact Evaluation Unit, housed within the Department of Management and Budget, is “tasked with producing high quality evidence about the efficacy and impact of state-funded programs.”[24]

Official actors aren’t the only ones conducting policy evaluation. Research organizations like universities and think tanks play an important role in policy evaluations. Some of the best evaluation work on health care comes from the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit organization.[25] Sometimes governments even contract with research organizations to conduct the evaluation. For example, the study about the St. Paul minimum income program that I mentioned earlier was conducted by the Center for Guaranteed Income Research at the University of Pennsylvania. News organizations and interest groups also both conduct and publicize the results of policy evaluation.

6.4 What do we do with evaluations?

A good policy evaluation will help us learn to create better policy and will hold government institutions accountable. Multiple scholars have worked to classify the types of learning that occur as a result of policy evaluation and in this section I present five of these ideas.

First, evaluation may produce government learning, that is, learning about how well the policy tools or implementation designs work to improve the delivery of policy.[26] Government officials can use evaluation to make organizational changes to implement policy more effectively.

Second, evaluation may produce policy-oriented learning, or learning about changes that can be made to policy to better achieve desired goals and objectives.[27] Sabatier argues that, unfortunately, it can be difficult for policymakers to believe evaluation information that contradicts their basic worldview and so most policymakers use evaluation to reinforce their existing policy beliefs.[28] However, there is some evidence to suggest the policymakers do learn from evidence and modify their policy beliefs even when the new information challenges their preexisting beliefs and preferences.[29]

Third, evaluation may provide lesson-drawing.[30] Policy makers learn negative and positive lessons from other venues that they apply to their own situation. In other words, policymakers look to other states, cities, or countries for inspiration and information about policies that work and don’t work. Then they use that information to make decisions about policies within their own venue. This type of learning is at the heart of the process of policy diffusion. Policy diffusion is the spread of policy ideas from one government to another (from one state to another, for example.) Learning from other venues is one of the primary forces behind policy ideas spreading between venues.[31]

Fourth, evaluation may provide social policy learning, which involves learning about how the social construction of a policy or problem affects how people perceive the government action.[32] Social policy learning involves changing the goals of a policy in response to what is learned through the process of evaluation.

Finally, evaluation may provide political learning, or learning about effective (and ineffective) strategies for advocating for a particular policy.[33] In essence, this is information that helps increase the political feasibility of a policy proposal. This is the type of learning on display in cases of mimicking (see chapter 3).

The information gleaned through evaluation can be helpful for reshaping policy moving forward. Often that process is slow and incremental, but sometimes policy change can be massive (remember Punctuated Equilibrium Theory from chapter 3?). But sometimes, the evaluation shows that the policy has simply failed. “A policy fails, even if it is successful in some minimal respects, if it does not fundamentally achieve the goals that proponents set out to achieve, and opposition is great and/or support is virtually non-existent.”[34] Policy evaluations that indicate a policy has failed usually come from single case studies, which makes it difficult to really understand the concept of policy failure because most of the research comes from cases society has already deemed to be examples of failure.

McConnell points out several challenges of defining policy failure. What one group views as a failure might reflect success to another group. For example, many Republicans view the Affordable Care Act as a failure while it is a resounding success in the eyes of many Democrats. Failure isn’t an “all or nothing” situation and it is hard to identify the tipping point between a policy that didn’t live up to all expectations and a policy that failed. Requiring police officers to wear body cameras during stops, for example, hasn’t resulted in the clarity supporters hoped for, but does that mean that cities should stop requiring it? A policy may be a failure for one target population but have positive benefits for another. Finally, situations might change over time and a policy that is seemingly failing at one point in time might be successful at an earlier or later time.

Regardless of whether a policy is deemed a failure or not, one simple truth remains and that is that government programs rarely end as a result of policy evaluation. That’s not to say that policies never go away; some policies are never reauthorized after their sunset clause expires, while others are rescinded or replaced through legislative action. But the feedback gained through policy evaluation–even when it is deemed a failure–is essential in the policymaking process.

Up to this point in the chapter, most of our focus has been on looking at policy that already exists (policy evaluation), but similar techniques are also used to estimate the possible effects of future policy (policy analysis).

6.5 What is a Policy Analysis Report?

A policy analysis report is a research-based document that describes a problem and identifies and evaluates alternative policy responses. A policy analysis report may or may not make a recommendation as to which alternative should be selected. Policy analysis is forward-looking, so it involves making some predictions based on data and it requires the analyst to consider and weigh competing values.

A policy analysis report is written for a specific audience and that audience will specify if they want a recommendation. The audience might be a supervisor or a client and that person/organization will have particular goals that the policy analysis should keep in mind. The length of a policy analysis report varies. Information may be provided in a short memo or it may be much longer.

The best resource for someone tasked with a policy analysis report is A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis by Eugene Baradach and Eric Patashnik.[35] In this book, Baradach and Patashnik outline eight steps in policy analysis and I’ll summarize them briefly here.

1. Define the problem

Step one involves defining the problem and Bardach and Patashnik recommend doing so in terms of deficit and excess (i.e. “too many” or “too small”). They warn policy analysts not to inadvertently include the solution as part of the problem. For example, “too many families are homeless” rather than, “there is too little shelter for homeless families.” This creates space for multiple policy alternatives to address the problem.

2. Assemble some evidence

As I mentioned earlier in this chapter, this is the step in the process that takes the most time. Bardach and Patashnik recommend that a policy analyst carefully thinks about what information they do and don’t need to collect rather than filling their time collecting unnecessary data. During this stage, analysts should review existing research, survey best practices, and identify possible analogies.

3. Construct the alternatives

Step three is all about brainstorming. The goal in this step is to identify as many policy alternatives as possible to address the policy problem. Bardach and Patashnik suggest asking questions like “how would you solve the problem if money were no object?” “where else would a solution work?” and “why not?” to help ensure a comprehensive list of alternatives. Once these alternatives are identified, come up with a very short sentence or phrase to label each alternative. At this stage, you can start to winnow your list of alternatives down to the best options, but don’t restrict the list too much yet.

4. Select the criteria

Step four establishes the mechanism for deciding between policy alternatives by articulating the criteria that will be used for making a decision. The most important criteria, Bardach and Patashnik tell us, is whether the alternative will solve the problem, but there are plenty of other criteria to consider that might influence a decision. Some common evaluation criteria include a numerical target or target date, efficiency, equality/equity/fairness/justice, freedom/community, or democratic process. Bardach and Patashnik argue that it is helpful to focus on a primary criterion to maximize (or minimize) and then to specify quantitative metrics that would indicate an increase or decrease in the criterion.

5. Project the outcomes

Bardach and Patashnik describe this as the hardest step. The challenge lies in the fact that the analyst is making a prediction about the future and none of us really knows what is going to happen in the future. The goal here is to be realistic about possible outcomes and to base them in reasonable assumptions and evidence rather than being overly optimistic. The starting point in projecting outcomes is establishing what Bardach and Patashnik call the “base camp.” The base camp is the condition that exists today and the alternatives are then described “in terms of the difference between what would (probably) exist tomorrow under the alternative and what (arguably) exists today.”[36] One useful suggestion for projecting outcomes is to create an outcomes matrix. The analysts lists policy alternatives in separate rows and evaluation criteria in columns and then fills in each cell with information. Bardach and Patashnik recommend putting the more important criteria in the more leftward columns to help in the next step.

6. Confront the trade-offs

Sometimes there is one clear winner among your alternatives, but usually there are going to be benefits and drawbacks of each alternative. In order to evaluate trade-offs, the analyst needs to convert alternatives into outcomes, particularly outcomes that can be stated as a monetary cost or savings. Bardach and Patashnik provide a few ways of negotiating trade-offs such as a break-even analysis, which involves identifying how much of a good must be produced in order to justify the costs of choosing it.

7. Stop, focus, narrow, deepen, decide

The seventh step of policy analysis is to take stock of the analysis so far and make sure that the alternatives that are rising to the top make sense. Bardach and Patashnik encourage an analyst to ask, “if your favorite policy alternative is such a great idea, how come it’s not happening already?” If, at this stage, you can’t convince yourself that a particular alternative offers the best path, it’s probably time to go back to an earlier stage of the process.

8. Tell your story

Finally, it’s time to communicate your story. As with any form of policy writing, it is important to keep the audience in mind. Bardach and Patashnik argue that the analysis needs a narrative flow that meets the interests and abilities of the audience. One common organizational structure is to begin by defining the problem and then describe each alternative within subsequent subsections. At the end, the analysis will summarize the alternatives and discuss any trade-offs. If the analyst has been asked to make a recommendation, this information should be included early in the report; remember that we’re not writing mystery novels!

In terms of style and presentation, Bardach and Patashnik encourage the use of headings and subheadings. If there are tables or figures in the document, be sure to number them and give them each a title. Include a list of references or sources at the end of the document (or presentation).

6.6 Why do you write?

Figure 6.3: Marcus Schmit ‘07, Executive Director of Hearth Connection, a nonprofit organization focused on homelessness and housing instability.

My career in public policy was shaped by a curiosity about the conflicts between groups of people and how leaders emerge to bring folks together, address issues and identify potential solutions, and move coalitions forward to improve people’s lives.

Two major events sparked my interest in public policy. Both events occurred within months of each other during my senior year of high school. First, a three-week teacher’s strike exposed the ugly politics that persist between labor and management, and raw division between neighbors in my small community. As the child of two public school teachers, I experienced firsthand the impact of the strike and endured 21 days of polarization within my community because individuals expected to lead in title and faculty failed to bring people together to solve problems and chart a path forward.

Second, only a few months later, the United States led a coalition of willing partners to topple Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq. Regardless of one’s viewpoint on that significant foreign policy decision, it generated considerable consequences for Iraq, the Middle East region, and the rest of the world that continue to impact us today.

These seminal events – one hyper local, another global – catalyzed my curiosity and passion for public policy at Gustavus where professors in the political science department challenged me to examine my predispositions, think critically about the issues of the day, and apply my strengths to discussion and problem-solving. However, I didn’t have this plan figured out on my first day “on the hill.” It took adapting to college living and three semesters of sampling other majors before I set my sights on a degree in political science. I seized opportunities to serve in student government and worked closely with department faculty, which grew my self confidence and my interest in a public policy career. That career commenced shortly after graduation when I found myself jobless after reneging on a two-year commitment to teach in New York City because I wanted to stay connected with family and friends and dive into the work I had studied. So I asked Tim Walz, a first-term Member of Congress at the time, for a job.

Two days later, on a Sunday morning, I drove to Mankato, Minnesota where I interviewed to be Congressman Walz’s district scheduler. This was a job I didn’t know existed three days earlier and it ended up being an opportunity that propelled me forward in diverse, exciting, impactful work for years to come. In addition to traveling around the district and working with staff in the congressional office and the campaign office to prioritize scheduling, I learned about agriculture and health care policy, built relationships with community leaders and veterans, and connected people from the district and Washington, DC.

After spending almost a decade with Congressman Walz, steadily gaining experience and increased responsibilities, I transitioned to new challenges in government affairs, public service, and nonprofit leadership all the while applying my knowledge of public policymaking and experience navigating our democratic institutions to improve people’s lives. I’ve forged lifelong friendships with many of my colleagues along the way and one thing is certain – everyone’s path to a public policy career is unique and shaped by their individual experiences.

I’ve learned that communicating concisely and effectively through the written word is an essential component of your success in public policy. Many of the opportunities to persuade decision-makers that your priority should also be their priority require developing an effective written message: submitting testimony in advance of an important legislative committee hearing, drafting a letter to the editor in 200 words or less, circulating an internal memorandum proposing a position change on a controversial policy with significant election implications, or crafting talking points for an elected official to prepare for a live-streaming press conference.

Time and attention spans are limited, so you need to drive an effective message before losing your audience and missing the moment to convince your reader. Done well, writing can lead to impactful change that improves people’s lives – and serve as a catalyst for your personal professional growth.

Long before gaining work experience and practical know-how, I poured over red inked responses to essays and policy memorandums in the annals of Old Main and Folke Bernadotte Memorial Library. Constructive feedback from Gustavus Adolphus College professors emphasizing avoidance of the passive tense and encouraging the development of coherent logical arguments prepared me well to produce quality writing on Day One as a congressional aide, where spent much of my time reviewing, editing, and organizing briefing memos for Members of Congress and their senior staff.

You may not yet realize how communicating concisely and effectively in the written word will influence your ability to chart and navigate an impactful, fulfilling career path. I could not imagine the myriad instances writing would shape my own. Here are a few examples:

- Generating a compelling cover letter articulating why you should be considered the preferred candidate by a hiring manager for a position that aligns your passion and talent;

- Crafting a briefing memorandum that provides critical context and talking points to inspire influencers and persuade decision-makers to change their approach to a significant local project in a manner that reflected community input and more effectively met the needs of thousands of residents;

- Producing a messaging campaign and legislative testimony that contributed to a multi-million dollar public investment in the construction of a regional food bank that opened its doors at the beginning of a global pandemic responsible for fueling layoffs, inflation, and food insecurity;

- Developing a two-year strategic plan for a nonprofit organization focused on addressing homelessness and housing instability across the state.

Without question, your ability to write effectively is linked to your success in public policy. Moreover, what you produce by way of pen and pad or keyboard clicks can captivate, inspire, persuade and improve the lives of thousands of people – and isn’t that the point of public policy?

6.7 What comes next?

That’s it for the theory section of this book. From here, we’ll move into exploring particular public policies. You’ll notice that each policy chapter introduces the topic and then uses the questions from each chapter in the first part of the book to organize information.

Questions for discussion:

- What are some public policies about which you have strong opinions? Is the information you have used to “evaluate” these policies primarily anecdotal or empirical?

- Consider a policy you care strongly about. What are some of the policy outputs associated with that policy? What are some of the policy outcomes associated with that policy?

- Are you personally more interested in policy evaluations (backwards-looking assessments) or policy analysis (forward-looking assessments)? For what reasons?

- Thinking about a policy you care strongly about, which type of evaluation seems most useful?

- Bardach and Patashnik argue that thinking is the most important step in policy evaluation but hustling data is the most time consuming. For what reasons do you think they reach this conclusion? Has this been true in research-based projects you have done in the past?

- What type of learning is most important (government learning, policy-oriented learning, lesson-drawing, social policy learning, political learning)? Why?

Glossary

Anecdotal evidence: Evidence based on personal experience.

Before-and-after study: Research design that looks at data from before a policy was implemented and compares it to data from after a policy was implemented

Cost-benefit evaluation: Evaluation that focuses on identifying the balance of costs versus benefits associated with a policy to determine whether the benefits outweigh the costs.

Empirical evidence: Systematic and objective evaluation of data using quantitative and/or qualitative social scientific research techniques.

Experimental design: Research design using a randomly selected experimental group and a control group to assess the impact of a particular variable (policy) on an outcome.

Government Accountability Office (GAO): Non-partisan, independent agency that conducts policy evaluations on behalf of Congress and executive agencies.

Government learning: Evaluation that results in learning about how well the policy tools or implementation designs work to improve the delivery of a policy.

Impact evaluation: Evaluation that focuses on the overall impact of a policy, including both intended and unintended consequences.

Lesson-drawing: Evaluation that results in learning negative and positive lessons from other venues that can be applied to different venues.

Master of Public Policy: A two-year graduate program for people who are interested in designing and evaluating public policy either in the public or private sector.

Master of Public Administration: A two-year graduate program for people who are interested in implementing and administering public policy in the public sector.

Office of Management and Budget (OMB): Office within the Executive Office of the President that oversees the effectiveness of agency programs and administration.

Outcome evaluation: Evaluation that focuses on whether the policy has achieved its goals.

Policy analysis: A forwards-looking process using data to make predictions about the effect and effectiveness of proposed public policies.

Policy diffusion: The spread of policy ideas from one government to another.

Policy evaluation: A backwards-looking process using data about existing policies to identify and understand successes and failures related to implementation and policy effects.

Policy outcomes: The results or consequences of a policy. May be intended or unintended.

Policy outputs: The actions a government agency takes or the things that a government agency produces in the process of implementing a policy.

Policy-oriented learning: Evaluation that results in learning about changes that can be made to policy to better achieve desired goals and objectives.

Political learning: Evaluation that results in learning about effective strategies for advocating for a particular policy.

Process evaluation: Evaluation that focuses on how well a policy is administered or implemented.

Quasi-experimental design: Also known as a natural experiment. Research design in which two groups are compared (but not randomly selected) to assess the impact of a particular variable (policy) on an outcome.

Social policy learning: Evaluation that results in learning about how the social construction of a policy or problem affects how people perceive the government action.

Theory of Change: An explanation of the expected causal chain between the policy and desired outcomes that explains how the policy is supposed to work.

Additional Resources

If you go into a career that involves policy analysis, I highly recommend that you get yourself a copy of this book for reference: Eugene Bardach and Eric M. Patashnik. A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving. (CQ Press 2020)

The Magenta Book: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5e96cab9d3bf7f412b2264b1/HMT_Magenta_Book.pdf

A Guide to Measuring Advocacy and Policy: https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf-aguidetomeasuringpolicyandadvocacy-2007.pdf

Data.gov is the federal government’s open-access data website: https://data.gov/

Minnesota’s Office of Management and Budget has a website with links to quality sources of evidence on various policy topics: https://mn.gov/mmb/results-first/finding-using-evidence/

If policy evaluation and/or policy analysis is something that sounds particularly interesting to you, you might consider pursuing a Master of Public Policy or a Master of Public Administration.

A Master of Public Policy (MPP) tends to involve more policy analysis but can also involve policy evaluation, focusing on the design and impact of policy. MPP students need to have good research skills (particularly quantitative skills) and should take some courses in both statistics and economics in preparation for graduate school. People who hold a MPP degree are often the ones designing public policy. The average salary for MPP graduates is $78,000 and graduates tend to hold job titles like Policy Analyst or Director of Government Affairs in either the public or private sector.

A Master of Public Administration (MPA) tends to involve more policy evaluation but can also involve policy analysis, focusing on the implementation and management of policy. MPA students need to have skills related to management, leadership, and budgeting and should take courses in management and communication. People who hold a MPA degree are often the ones implementing public policy. The average salary for MPA graduates is $75,000 and graduates tend to hold job titles like City Manager or Government Program Manager in the public sector.

Thanks for reading this chapter. The book in which this chapter sits is a work in progress and I welcome feedback and suggestions for improvement. If you notice incorrect or out of date information, please let me know using the feedback form linked below. If something was particularly helpful to you, I’d also love to hear about it. If you are a faculty member or public policy practitioner who is interested in collaborating on this project, you can also use this feedback form to contact me. ~Kate

Feedback form: https://forms.gle/LKBykHHRLe2kNW2AA

- If you need a reminder, this was the case that overturned the Court’s precedents from Roe v. Wade (1973) and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992). The Court’s decision in Dobbs upheld a Mississippi law that banned nearly all abortions after 15 weeks in finding that the U.S. Constitution does not confer a right to an abortion. ↵

- As of the end of 2023, 21 states have passed laws that ban medication and/or surgical care for transfender youth. For more information about the states, see: https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/healthcare_youth_medical_care_bans ↵

- https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/federal-spending/#federal-spending-overview ↵

- The four types of evaluation I summarize are based on the categories described by Stella Z. Theodoulou and Chris Kofinis in The Art of the Game: Understanding American Public Policy Making. (California: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2004). ↵

- The name “outcome evaluation” is actually a bit confusing because so much of it “is concerned with outputs” (p. 193). ↵

- Michael E. Kraft and Scott R. Furlong, Public Policy: Politics, Analysis, and Alternatives 7th Edition (California: CQ Press, 2021), 180-181. ↵

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5e96cab9d3bf7f412b2264b1/HMT_Magenta_Book.pdf ↵

- https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf-aguidetomeasuringpolicyandadvocacy-2007.pdf ↵

- Eugene Bardach and Eric M. Patashnik, A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving (California: Sage/CQ Press, 2020), 14. This passage makes me chuckle, which is why I had to include it even though it’s a little ironic coming from Bardach and Patashnik’s book about eight steps in policy analysis. ↵

- An operational definition is the explanation of how a researcher will measure a concept. Sometimes researchers turn this into a verb to talk about “operationalizing” a concept. ↵

- Some of you are having Analyzing Politics flashbacks here. ↵

- You can read more about it in the final report here: https://content.govdelivery.com/attachments/STPAUL/2023/12/18/file_attachments/2721687/CGIR Final Report_Saint Paul PPP_2023.pdf ↵

- David Card and Alan B. Krueger, “Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania,” American Economic Review 84, no. 4 (September 1994): 772-793. ↵

- Department of Health and Human Services Office of Health Policy, Access to Preventative Services without Cost-Sharing: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act. (January 11, 2022), https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/786fa55a84e7e3833961933124d70dd2/preventive-services-ib-2022.pdf ↵

- Frank R. Baumgartner, Derek A. Epp, and Kelsey Shoub, Suspect Citizens: What 20 Million Traffic Stops Tell Us about Policing and Race. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). ↵

- The statute was expanded to cover nearly all law enforcement agencies in 2001. ↵

- Technically, the word “data” is technically a plural noun (datum is the singular version), but it sounds weird to treat it as plural in some contexts and major newspapers are moving away from the standard. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_(word) for more information. ↵

- The federal government maintains a website with information about the Evidence Act in practice: https://www.evaluation.gov/ ↵

- You can read the entire Commission report here: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Full-Report-The-Promise-of-Evidence-Based-Policymaking-Report-of-the-Comission-on-Evidence-based-Policymaking.pdf ↵

- https://www.gao.gov/ ↵

- Policy evaluation is only one part of the GAO’s work; they also audit federal agencies to ensure that money is being spent properly, investigate allegations of wrongdoing, and make recommendations to Congress and executive agencies. ↵

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/ ↵

- https://www.oversight.gov/about ↵

- https://mn.gov/mmb/impact-evaluation/ ↵

- https://www.kff.org/ ↵

- The term government learning comes from Colin J. Bennett and Michael Howlett, “The Lessons of Learning: Reconciling Theories of Policy Learning and Policy Change,” Policy Sciences 25, no. 3 (1992): 275-294. The concept is similar to May’s conception of instrumental policy learning: Peter J. May, “Policy Learning and Failure.” Journal of Public Policy 12, no. 4 (1992): 331-354. ↵

- Paul Sabatier, “An Advocacy Coalition Framework of Policy Change and the Role of Policy-Oriented Learning Therein,” Policy Sciences 21, no.2/3 (1988): 129-168. ↵

- Paul Sabatier, “An Advocacy Coalition Framework of Policy Change and the Role of Policy-Oriented Learning Therein,” Policy Sciences 21, no.2/3 (1988): 129-168, 133. ↵

- Nathan Lee, “Do Policy Makers Listen to Experts? Evidence from a National Survey of Local and State Policy Makers,” American Political Science Review 116, no. 2 (2022): 677-688. ↵

- Richard Rose, “What is Lesson-Drawing?” Journal of Public Policy 11, no. 1 (1991): 3-30. ↵

- Charles R. Shipan and Craig Volden, “The Mechanics of Policy Diffusion,” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 4 (October 2008): 840-857. ↵

- Peter A. Hall, “Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State: The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain,” Comparative Politics 25, no. 3 (April 1993): 275-296; Peter J. May, “Policy Learning and Failure,” Journal of Public Policy 12, no. 4 (1992): 331-354. ↵

- Colin J. Bennett and Michael Howlett, “The Lessons of Learning: Reconciling Theories of Policy Learning and Policy Change,” Policy Sciences 25, no. 3 (1992): 275-294. Peter J. May, “Policy Learning and Failure,” Journal of Public Policy 12, no. 4 (1992): 331-354. ↵

- Allan McConnell, “What is Policy Failure? A Primer to Help Navigate the Maze,” Public Policy and Administration 30, no 3-4 (2015): 230. ↵

- Eugene Bardach and Eric M. Patashnik, A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving (California: Sage/CQ Press, 2020). ↵

- Eugene Bardach and Eric M. Patashnik, A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving (California: Sage/CQ Press, 2020), 51. ↵

Evidence based on personal experience.

Systematic and objective evaluation of data using quantitative and/or qualitative social scientific research techniques.

The actions a government agency takes or the things that a government agency produces in the process of implementing a policy.

The results or consequences of a policy. May be intended or unintended.

Efforts by government and other policy actors (like academics!) to find out whether the policy was effective in reaching its intended goals.

A forwards-looking process using data to make predictions about the effect and effectiveness of proposed public policies.

Evaluation that focuses on how well a policy is administered or implemented.

Evaluation that focuses on whether the policy has achieved its goals.

Evaluation that focuses on the overall impact of a policy, including both intended and unintended consequences.

Evaluation that focuses on identifying the balance of costs versus benefits associated with a policy to determine whether the benefits outweigh the costs.

An explanation of the expected causal chain between the policy and desired outcomes that explains how the policy is supposed to work.

Research design using a randomly selected experimental group and a control group to assess the impact of a particular variable (policy) on an outcome.

Also known as a natural experiment. Research design in which two groups are compared (but not randomly selected) to assess the impact of a particular variable (policy) on an outcome.

Research design that looks at data from before a policy was implemented and compares it to data from after a policy was implemented.

Non-partisan, independent agency that conducts policy evaluations on behalf of Congress and executive agencies.

An office that conducts independent audits and investigations of an agency to detect and prevent fraud and abuse.

Evaluation that results in learning about how well the policy tools or implementation designs work to improve the delivery of a policy.

Evaluation that results in learning about changes that can be made to policy to better achieve desired goals and objectives.

Evaluation that results in learning negative and positive lessons from other venues that can be applied to different venues.

The spread of policy ideas from one government to another.

Evaluation that results in learning about how the social construction of a policy or problem affects how people perceive the government action.

Evaluation that results in learning about effective strategies for advocating for a particular policy.

A two-year graduate program for people who are interested in designing and evaluating public policy either in the public or private sector.

A two-year graduate program for people who are interested in implementing and administering public policy in the public sector.

A particularly important office within the executive branch that is responsible for preparing the president’s annual budget proposal and reviewing all proposed bills and agency regulations.